Abstract

Purpose

A dedicated otolaryngology emergency room (ER) represents a specialized surgical evaluation and treatment setting that may be an alternative triage pathway for acute otolaryngologic complaints. We aim to characterize practice patterns in this setting and to provide insight into the epidemiology of all-comer, urgent otolaryngologic complaints in the United States.

Methods and Methods

Electronic medical records were reviewed for all patients who registered for otolaryngologic care and received a diagnosis in the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary ER between January 2011 and September 2013. Descriptive analysis was performed to characterize utilization and diagnostic patterns. Predictors of inpatient admission were identified using multivariable regression. Geocoding analysis was performed to characterize catchment area.

Results

A total of 12,234 patient visits were evaluated with a mean age of 44.7. Auditory and vestibular problems constituted the most frequent diagnoses (50.0%). The majority of patients were discharged home (92.3%). Forty-three percent of patients underwent a procedure in the ER; the most common procedure was diagnostic nasolaryngoscopy (52%). Predictors of inpatient admission were post-operative complaint (odds ratio [OR] 7.3, p<0.0001), arrival overnight (OR 3.3, p<0.0001), and laryngeal complaint (OR 2.4, p<0.0001). Patients travelled farther for evaluation of hearing loss (11 miles) and less for common diagnoses including impacted cerumen (7.1 miles) (p<0.0001).

Conclusion

In this report, we investigate practice patterns of a dedicated otolaryngology emergency room to explore an alternative to standard acute otolaryngologic health care delivery mechanisms. We identify key predictors of inpatient admission. This study has implications for emergency health care delivery models.

Keywords: Otolaryngology, emergency room, specialized emergency care, resource utilization

INTRODUCTION

Acute otolaryngologic complaints are common and range from ear pain and hearing loss to cases of severe epistaxis and airway compromise. According to the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2,361,000 patients were seen in an emergency room for otitis media and Eustachian tube disorders in 2010 alone.1 It is estimated that upwards of ten percent of new consultations in primary care offices are related to ear, nose or throat disorders, many of which may require urgent evaluation and treatment.2 With the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, the number of insured Americans is expected to rise, resulting in a projected shortage of otolaryngologists.3 As a result, the burden of acute otolaryngologic care in both outpatient and standard emergency room practice settings will increase in the near future.3,4

Traditional emergency rooms (ER) are saturated beyond their intended capacity, resulting in long wait times and potentially inferior outcomes.5–7 Dedicated otolaryngology-specific emergency rooms (ER) are largely uncommon in the United States and not well described in the otolaryngology literature. As a significant number of complaints seen in emergency departments are otolaryngologic in nature, an otolaryngology ER may theoretically relieve pressures of traditional ERs and improve patient outcomes by increasing access to specialist care.1,2 Otolaryngology ERs have been described in other countries, including, Greece, Spain, Israel, Brazil, France and India8–16, and take the form of stand-alone emergency rooms15, integrated units in hospital emergency departments8,11, urgent care clinics12,13, or full-time emergency services in a hospital9. Otologic disorders represent a common indication for referral or utilization of a specialized otolaryngology ER in these previous reports. Some facilities manage a higher volume of trauma, foreign body, or epistaxis that require urgent treatment14 whereas others institutions describe care that is predominantly for patients with common otolaryngologic complaints such as otitis media, otitis externa and sinusitis.8

At the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary (MEEI), a dedicated stand-alone otolaryngology emergency room (ER) provides specialty care to any patient with otolaryngologic complaints twenty four-hours per day, seven days per week, 365 days per year. This ER functions similarly to a standard ER, albeit on a smaller scale. Patients are frequently transferred from community-based emergency rooms without otolaryngologic coverage or outpatient clinics for acute otolaryngologic evaluation. A CT and magnetic resonance imaging scanner available 24 hours per day, as well as audiologic evaluation by audiologists. Patients can be admitted to the MEEI otolaryngology inpatient service or can be triaged directly to the operating room in an expeditious fashion. The MEEI ER is adjacent and physically connected to the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and patients with life-threatening illness or non-otolaryngologic complaints may be rapidly transferred directly to the MGH ER. Descriptive trends in the MEEI emergency room were last characterized 30 years ago as a short communication article.15

There is no contemporary analysis of practice patterns or utilization trends for an otolaryngology ER in the United States. In the context of rising healthcare costs and new models of healthcare delivery, this study seeks to investigate a unique venue for acute otolaryngologic care. We aim to provide a comprehensive, descriptive analysis of patient demographics, visit characteristics and the range of otolaryngologic complaints in this unique acute care setting. This study can be viewed as a baseline evaluation and starting point of a discussion regarding acute otolaryngologic care in the United States.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Electronic medical records were reviewed for all patients who registered for otolaryngologic care and received a diagnosis in the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary (MEEI) emergency room (ER) between January 2011 and September 2013. Patients that eloped prior to evaluation by a physician, incomplete records, and duplicate patient entries were excluded. The MEEI ER also treats ophthalmologic complaints, and patients with dual registration were excluded from analysis. Patient demographics, visit characteristics, diagnostic and procedural data were extracted. Institutional review board approval from the MEEI Human Studies Committee was obtained in advance.

Primary diagnosis was recorded using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9CM) codes. Diagnoses were grouped into twelve categories according to functional system or anatomical location based on group consensus. These categories included auditory and/or vestibular, nasal and/or sinus, oral cavity, pharyngeal and/or esophageal, laryngeal and/or tracheal, cutaneous and/or orthopedic, trauma, neck, face and/or glands, neurological, post-operative complication and other. Procedures were recorded using the American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Similar or identical procedures with different CPT codes were grouped together into seven categories. These included indirect nasolaryngoscopy (rigid and flexible), ear debridement, control of epistaxis, drainage of peritonsillar abscess, incision and drainage of lesion, removal of foreign body and all other procedures. Control of epistaxis was defined as the diagnosis or further management of nasal bleeding based on diagnostic and procedural CPT codes. Pediatric patients were defined as age less than or equal to 18 years. Time of arrival was assigned as daytime (6am to 7pm) or overnight (7pm to 6am). Patients were defined as “new” if there was no existing medical record number in the electronic medical record system at MEEI on arrival.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed to characterize patient demographics, including age, gender and race. Visits were characterized by time of arrival, weekday versus weekend, and ultimate disposition. Diagnostic and procedural categories were tabulated as were the top 10 individual diagnoses by frequency. Differences in demographic and visit characteristics were also compared for each of the seven diagnostic categories. Monthly trends in average volume were plotted for the top five diagnoses.

Descriptive characteristics were also compared between new versus established patients, children versus adults, arrival during the daytime versus overnight, and admitted versus discharged patients. Comparison of means was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test while comparison of proportions was performed using chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. A fixed-effects multivariable logistic regression model inclusive of all independent variables was created to identify significant predictors of inpatient admission. All data manipulation and analysis was performed using STATA v.13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Geocoding and choropleth maps

Geocoding analysis was performed to characterize the catchement area for the entire patient cohort. Median travel distance was calculated using the Google™ Geocoding Application Programming Interface in STATA to estimate road distance, as navigated by an automobile, between two geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude).17 Travel distance for cohorts defined by specific diagnosis, visit day (weekend versus weekday), new versus established, and pedatric versus adult were compared by median quantile regression. The central geographic coordinates of each patient’s zip code were used as the starting point and coordinates of the MEEI ER as the end point.

Choropleth maps, or visually-graded representations of frequency or density within predefined areas, were generated to depict patient volume by county of origin within the state of Massachussetts. Maps were generated using the Epi Info™ v7.1.3 software published by the Centers for Disease Control.18

RESULTS

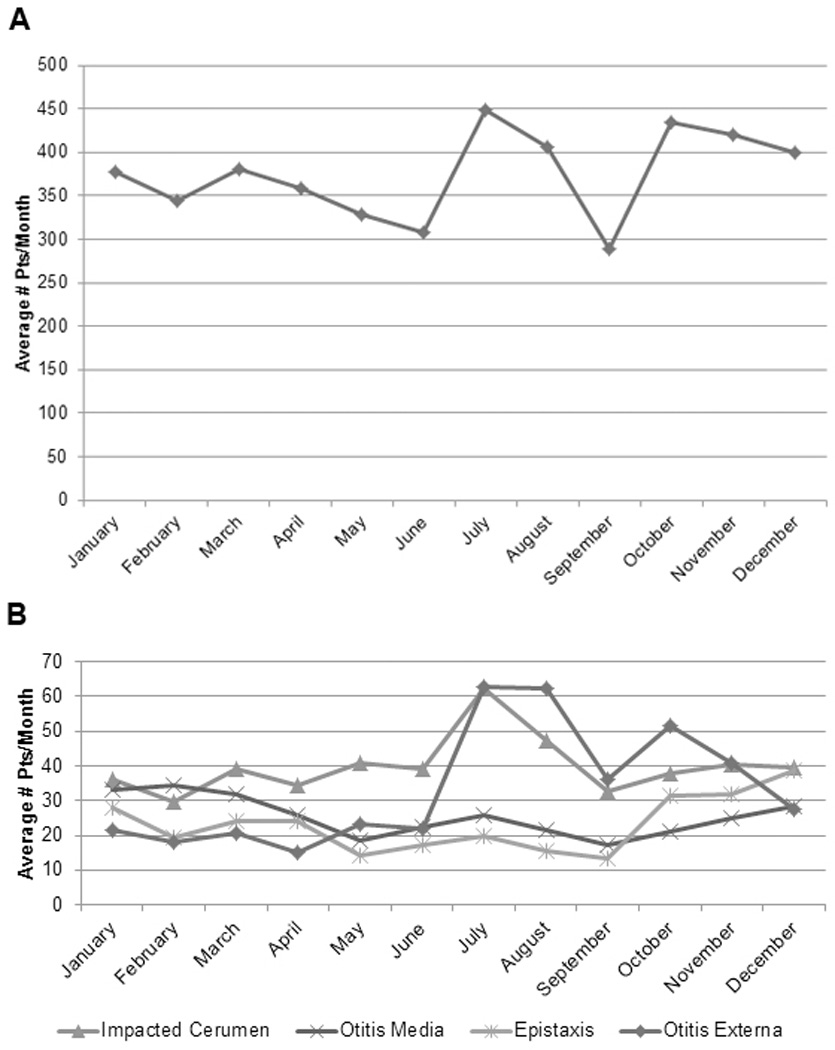

We included in our analysis a total of 12,234 patients who received a diagnosis in the MEEI ER for an otolaryngologic complaint between January 2011 and September 2013. Over 4,000 patients were examined annually. Thirty-one percent of patients (N=3,883) were first-time visitors. The average age was 44.8 years (standard deviation [SD] = 21.3 years), 50.3% were female and the majority were adults (89.2%) (Table 1). The average monthly volume was 370.7 patients (SD=83.8). Most patients arrived during the daytime (87.1%), Monday through Friday (74.7%). Figure 1 demonstrates a cyclic pattern in average monthly volume with a peak in July (449 patients/month, SD=45.9) and nadir in September (289 patients/month, SD=139.5). The vast majority of patients were discharged home (92.3%).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics for all patients and stratified by new versus established patients.

| Characteristic | All patients (N=12,234) |

New Patients (N=3,883) |

Est. Patients (N=8,351) |

P-value (New vs. Est.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median | 45 | 34 | 50 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 44.8 (21.3) | 37.2 (18.6) | 48.3 (21.6) | <0.0001 |

| Age, range | 2–97 | 2–97 | 2–97 | |

| Age category | <0.0001 | |||

| Pediatric (0–18 years) | 1,327 (10.9) | 484 (12.5) | 843 (10.1) | |

| Adult (>18 years) | 10,907 (89.2) | 3,399 (87.5) | 7,508 (89.9) | |

| Gender | 0.532 | |||

| Male, No. (%) | 6,081 (49.7) | 1,914 (49.3) | 4,167 (49.9) | |

| Female, No. (%) | 6,153 (50.3) | 1,969 (50.7) | 4,184 (50.1) | |

| Race | <0.0001 | |||

| White, No. (%) | 9,738 (79.6) | 3,046 (78.4) | 6,692 (80.1) | 0.031 |

| African American, No. (%) | 1,017 (8.3) | 313 (8.1) | 704 (8.4) | 0.491 |

| Asian, No. (%) | 409 (3.3) | 185 (4.8) | 224 (2.7) | <0.0001 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native, No. (%) | 78 (0.6) | 39 (1.0) | 39 (0.5) | 0.001 |

| Other/unknown, No. (%) | 992 (8.1) | 300 (7.7) | 692 (8.3) | 0.290 |

| Hispanic | 0.136 | |||

| Yes | 399 (3.3) | 113 (2.9) | 286 (3.4) | |

| No | 11,835 (96.7) | 3,770 (96.9) | 8,065 (96.6) | |

| Disposition | <0.0001 | |||

| Home, No. (%) | 11,291 (92.3) | 3,676 (94.7) | 7,615 (91.2) | |

| Inpatient/Observation, No. (%) | 943 (7.71) | 207 (5.3) | 736 (8.8) | |

| Year of visit | 0.041 | |||

| 2011 | 4,934 (40.3) | 1,323 (34.1) | 2,905 (34.8) | 0.439 |

| 2012 | 4,228 (34.6) | 1,529 (39.4) | 3,405 (40.8) | 0.143 |

| 2013* | 3,072 (25.1) | 1,031 (26.6) | 2,041 (24.4) | 0.012 |

| Time of visit | 0.207 | |||

| Daytime (6a-7p) | 10,653 (87.1) | 3,403 (87.6) | 7,250 (86.8) | |

| Overnight (8p-5a) | 1,581 (12.9) | 480 (12.4) | 1,101 (13.2) | |

| Day of visit | 0.614 | |||

| Weekday (M-F) | 9,141 (74.7) | 2,890 (74.4) | 6,251 (74.9) | |

| Weekend (S-S) | 3,093 (25.3) | 993 (25.6) | 2,100 (25.1) |

2013 includes visits between January and September only, Est.=Established

FIGURE 1.

Monthly patient volume (A), stratified by four most common diagnoses (B).

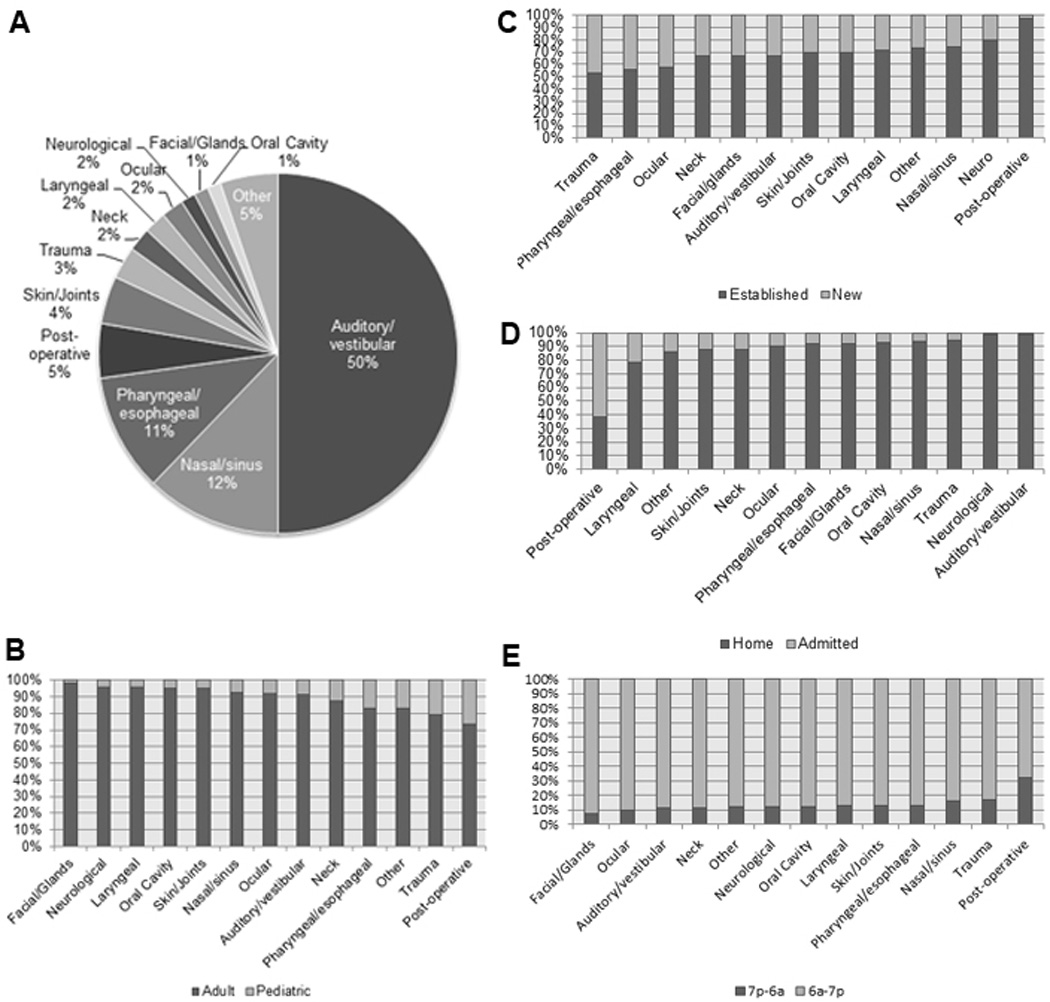

The most frequent presenting complaints were related to the auditory or vestibular system (50.0%) (Figure 2). A total of 651 unique diagnoses were made in the ER. The five most common were impacted cerumen (10.8%), otitis externa (8.9%), otitis media (6.9%), epistaxis (6.0%) and hearing loss (5.6%) (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of head and neck systems by frequency of presenting complaints (A), stratified by pediatric versus adult patients (B), new versus established patients (C), inpatient admission versus home discharge (D), and overnight versus daytime arrival (E).

Table 2.

Ten most common diagnoses among all patients

| Diagnosis | All Patients (N=12,234) |

|---|---|

| Impacted cerumen, No. (%) | 1,322 (10.8) |

| Otitis externa, No. (%) | 1,085 (8.9) |

| Otitis media, No. (%) | 840 (6.9) |

| Epistaxis, No. (%) | 731 (6.0) |

| Hearing loss, No. (%) | 687 (5.6) |

| Sinusitis, No. (%) | 547 (4.5) |

| Otalgia, No. (%) | 495 (4.1) |

| Dizziness or vertigo, No. (%) | 362 (3.0) |

| Trauma, No. (%) | 354 (2.9) |

| Tonsillitis, No. (%) | 342 (2.8) |

A total of 5,664 patients (46.3%) underwent a non-operative procedure in the ER. These procedures, in order of frequency, were diagnostic nasolaryngoscopy (52.0%), ear debridement (34.4%), management of epistaxis (7.0%), incision and drainage of lesion (1.7%), drainage of peritonsillar abscess (1.7%) and removal of foreign body (0.8%). The most common diagnostic categories associated with procedural intervention were complaints related to the auditory/vestibular (49%) and nasal/sinus (20%) systems.

Stratified analysis was performed to identify demographic and diagnostic differences between new and established, pediatric and adult, daytime and overnight, and patients that were admitted and discharged. Bivariable comparisons are summarized in supplemental appendices published online.

A small percentage of patients examined in the ER were admitted for inpatient treatment or observation (N=943, 7.7%). In multivariable logistic regression modeling, significant predictors of inpatient admission included pediatric designation (Odds ratio [OR] 1.9, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.5–2.3, P <0.0001), male gender (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1–1.6, P<0.0001), arrival overnight (OR 3.3, 95% CI 2.7–3.9, P<0.0001), post-operative complaint (OR 7.3, 95% CI 5.4–9.9, P<0.0001) and laryngeal complaint (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.6–3.7, P<0.0001). Additional factors were associated with decreased odds of admission and are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis predicting outcome of inpatient admission for all patients

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (vs. female) | 1.34 | 1.14–1.57 | <0.0001 |

| Pediatric (vs. adult) | 1.86 | 1.51–2.29 | <0.0001 |

| Weekend (vs. weekday) | 1.13 | 0.95–1.35 | 0.166 |

| Overnight (vs. Daytime) | 3.26 | 2.71–3.94 | <0.0001 |

| New patient (vs. established) | 1.08 | 0.90–1.31 | 0.897 |

| Procedure in the ER (yes vs. no) | 0.17 | 0.14–0.21 | <0.0001 |

| Sinonasal symptoms (yes vs. no) | 0.77 | 0.55–1.07 | 0.114 |

| Pharyngeal/esophageal symptoms (yes vs. no) | 0.55 | 0.40–0.76 | <0.0001 |

| Laryngeal symptoms (yes vs. no) | 2.43 | 1.61–3.68 | <0.0001 |

| Post-operative symptoms (yes vs. no) | 7.31 | 5.41–9.89 | <0.0001 |

| Trauma (yes vs. no) | 0.25 | 0.15–0.43 | <0.0001 |

| Cutaneous/orthopedic symptoms (yes vs. no) | 0.74 | 0.52–1.07 | 0.108 |

| Ocular symptoms (yes vs. no) | 0.51 | 0.31–0.85 | 0.010 |

| Oral cavity symptoms (yes vs. no) | 0.49 | 0.25–0.96 | 0.038 |

| Neck symptoms (yes vs. no) | 0.02 | 0.58–1.45 | 0.717 |

| Facial and/or glandular symptoms (yes vs. no) | 0.47 | 0.24–0.89 | 0.022 |

| Neurological symptoms (yes vs. no) | 0.07 | 0.02–0.31 | <0.0001 |

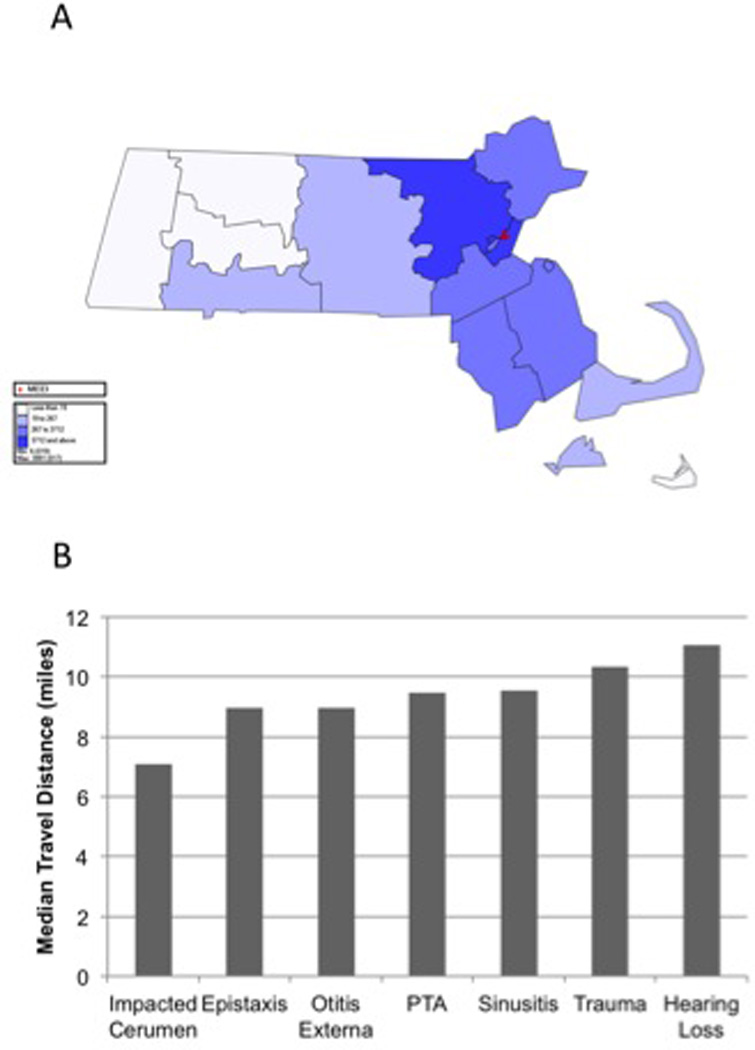

Patients originated from 42 states although 93% were from Massachusetts. Over ninety-percent of patients lived within a 50-mile radius of the MEEI ER. For all patients, median travel distance was 9.6 miles. Established patients (9.4 miles) and new patients (9.6 miles) travelled similar distances (P=0.535). Visitors traveled similar distances for pediatric care (9.5 miles vs. 8.3 miles for an adult, P=0.811). Patients were willing to travel farther to seek specialized otolaryngologic care it was a weekend (11.1 miles vs. 8.2 miles on a weekday, P<0.0001). Patients with hearing loss (11.1 miles) and trauma (10.3 miles) travelled the furthest whereas those with impacted cerumen (7.1 miles) travelled the least (P<0.0001) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Choropleth maps depicting frequency of patients by Massachusetts counties (A). Travel distance by diagnosis (B).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we aim to describe practice patterns of a dedicated otolaryngology emergency room to explore an alternative to standard acute otolaryngologic health care delivery mechanisms. To our knowledge, this is the first contemporary in-depth study to provide insight into the epidemiology of all-comer, urgent otolaryngologic complaints in the United States. From 2011 to 2013, we identified 12,234 patients that were evaluated in the otolaryngology ER by otolaryngology residents under the supervision of an attending otolaryngologist; patients were found to be predominantly adult, middle-aged men and women who visited the ER during daytime hours (75%) with peak volume occurring mid-day (11am to 1pm). Over 90% of patients were discharged home the same day; inpatient admission was associated with presentation overnight or during the weekend, and with post-operative complaints. The predominance of daytime patients who are discharged home with non-emergent diagnoses is not surprising and similar to case distribution in standard ERs.19–20

A wide range of complaints and diagnoses were seen in our institution’s otolaryngology ER, however, the overwhelming majority were non-emergent. One in every two patients presented with auditory or vestibular complaints and the three most common diagnoses were impacted cerumen, otitis media and otitis externa. As expected there was seasonal variation in diagnoses with higher prevalence of otitis media and otitis externa in the summer months and epistaxis in the winter months. Children more frequently presented with pharyngeal/esophageal and post-operative complaints, while adults had auditory/vestibular and sinonasal symptoms. Indeed, an important question is whether patients evaluated in a specialized otolaryngology ER have diagnoses requiring immediate, specialized evaluation and treatment. In the MEEI ER, emergent conditions, including epistaxis (6%), acute hearing loss (6%), head and neck trauma (3%), were largely uncommon. Acute pathology was more commonly seen during the overnight period, including a higher prevalence of trauma (4%) and post-operative complaints (12.1%). These data are similar to utilization patterns reported in other specialized otolaryngology ERs.13

In this study, we also employed geocoding techniques to analyze practice patterns in the acute care setting to determine if distance was a factor in diagnosis. As expected, the majority of patients (93%) originate from Massachusetts. The median distance travelled was 9.6 miles, suggesting that the patients live within close proximity. Patients travelled greater distances for evaluation of hearing loss (11.1 miles) and trauma (10.3 miles) and shorter distances for impacted cerumen (7.1 miles). Additionally, patients examined on weekends travelled farther (11.1 miles) than patients seen on a weekday (8.2 miles). It is unclear from the current study why patient complaints influence travel distances. Patients may perceive hearing loss and trauma as requiring more specialized emergency care. Further, utilization of a specialty ER for evaluation of minor complaints, such as impacted cerumen, may be motivated by the perceived convenience of shorter wait times as compared to standard ERs. While only limited conclusions can be drawn from this geocoding analysis in this single-institution study, we anticipate this type of analysis will serve as the basis for future studies and may be used at the national level to address key questions of resource utilization.

There are unfortunately no contemporary comparison data on care patterns in otolaryngology emergency rooms in the United States; however, diagnostic and utilization trends observed in the MEEI ER are consistent with global trends in emergency otolaryngologic care in specialized ERs. The high prevalence of ear-related complaints seen in the MEEI ER was similar to a high complexity hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil (60% of all visits) and also to a specialized otolaryngology emergency clinic at a tertiary care center in Barcelona.8,21 At the Laiko Univeristy Hospital Ear Nose and Throat Emergency Department in Greece, over 33,000 patients were examined between 2001 and 2006.11 The most common diagnoses included acute tonsillitis (12.5%), acute pharyngitis (11.4%), otitis externa (5.9%), otitis media (2.6%) and acute sinusitis (4.2%). Finally, at the Strasbourg Hospital ENT Emergency Clinic in France, 8.4 patients were seen daily over a six month study period and the predominant diagnoses was otitis externa, otitis media, epistaxis, vertigo and facial injuries.10 While these institutions exist in fundamentally different healthcare environments, it is notable that the diagnostic trends are comparable.

As a concluding note, our preliminary data and those of previous studies suggest that emergency medicine physicians and otolaryngologists should partner to discuss healthcare policy around emergency room-based otolaryngologic care.7,22 At baseline, initial access to subspecialty care may help decompress the volume of ED visits thereby preventing longer wait times and ensuring that patients with true emergencies have timely access to care. The Institute of Medicine Committee on the Future of Emergency Care recommended the development of a regionalized system of emergency care to increase access to specialty care.23 In a regionalized system, hospitals, emergency care providers, nurses and administrators work together to coordinate expertise and distribution of resources. The model of direct access to specialists is currently in development for patients with diagnoses of cardiac arrest and stroke, as well as for pediatric patients.23 While all otolaryngologic complaints often do not require specialist-level care, a regionalized system of expertise, whether a stand-alone ER or a dedicated team focused on otolaryngologic complaints by emergency room and/or otolaryngology providers, may lead to improved care coordination and address many of the concerns previously introduced. Moreover, as the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act nears completion, the anticipated number of common otolaryngologic complaints seen in EDs will likely increase significantly. The dedicated otolaryngology ER described herein may serve as a potential initial model.

Our study has several limitations. Our own outcomes and outcomes for patients with urgent otolaryngologic complaints examined in standard ERs have not been published, limiting our ability to comment on the comparative effectiveness of specialized otolaryngology ER. We were also not able to include in the analysis details of patients that eloped, and it is unclear the range of potential diagnoses in this patient cohort. Patients that were evaluated initially by ophthalmologists and subsequently seen by otolaryngologists in the ED were excluded. This exclusion may decrease the number of patients with overlapping acute diagnoses, such as orbital cellulitis. Given the large range of patient complaints and diagnoses, and lack of formal grouping systems for common otolaryngologic complaints in the literature, we elected to group diagnoses by anatomical location and systems. This categorization method may not account for patients with diagnoses that overlap anatomical areas of functional systems. Finally, evaluating the cost-effectiveness or comparative-effectiveness of a specialized otolaryngology ER was beyond the scope of this study. Despite these weaknesses, our study, provides an initial example of an alternative model to contemporary acute otolaryngologic care, which is currently delegated to hospital-based ERs and urgent care clinics, and worthy of further discussion given changing health care climate, rising healthcare costs, and evolving payer models.

CONCLUSION

This study represents an in-depth analysis of emergency otolaryngologic care in the United States at an otolaryngology-specific emergency room. This study has broad implications for otolaryngology care and resource management in the emergency setting. Our investigation may serve as comparison for future studies of acute otolaryngology care both at the local and national level. Furthermore, we anticipate this study will raise questions regarding current practice patterns, as well as whether different health care delivery models may improve access to otolaryngologists in the acute setting.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Fran McDonald, Senior System Analyst, of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary for her thoughtful approach to data acquisition and analysis. RKVS and EDK had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

FUNDING:

None

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

R.K.V.S., E.D.K., A.K.R., S.T.G., M.G.S., and R.E.G. have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Emergency Department Summary Tables. Centers for Disease Control; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths E. Incidence of ENT problems in general practice. J R Soc Med. 1979 Oct;72(10):740–742. doi: 10.1177/014107687907201008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reger C, Kennedy DW. Changing practice models in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: the role for collaborative practice. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009 Dec;141(6):670–673. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharyya N. Involvement of physician extenders in ambulatory otolaryngology practice. Laryngoscope. 2012 May;122(5):1010–1013. doi: 10.1002/lary.23274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caldwell N, Srebotnjak T, Wang T, Hsia R. "How much will I get charged for this?" Patient charges for top ten diagnoses in the emergency department. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hing E, Bhuiya F. Wait Time for Treatment in Hospital Emergency Departments: 2009. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency M. Overcrowding crisis in our nation's emergency departments: is our safety net unraveling? Pediatrics. 2004 Sep;114(3):878–888. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrade JS, Albuquerque AM, Matos RC, Godofredo VR, Penido Nde O. Profile of otorhinolaryngology emergency unit care in a high complexity public hospital. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2013 May-Jun;79(3):312–316. doi: 10.5935/1808-8694.20130056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saha S, Chandra S, Mondal PK, et al. Emergency Otorhinolaryngolocal cases in Medical College, Kolkata-A statistical analysis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005 Jul;57(3):219–225. doi: 10.1007/BF03008018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herve JF, Wiorowski M, Schultz P, et al. ENT Resident Activity in the Strasbourg Hospital ENT Emergency Clinic. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2004 Feb;121(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0003-438x(04)95488-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasileiou I, Giannopoulos A, Klonaris C, et al. The potential role of primary care in the management of common ear, nose or throat disorders presenting to the emergency department in Greece. Quality in primary care. 2009;17(2):145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia Lozano MC, Munoz Platon E, Jimenez Antolin J, Galan Morales JT, Galdeano Granda E. Outpatient ENT hospital emergencies: a descriptive study of one year of services. An Otorrinolaringol Ibero Am. 1997;24(6):601–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Timsit CA, Bouchene K, Olfatpour B, Herman P, Tran Ba Huy P. Epidemiology and clinical findings in 20,563 patients attending the Lariboisiere Hospital ENT Adult Emergency Clinic. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2001 Sep;118(4):215–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perez Obon J, Rivares Esteban J, Leache Pueyo J, et al. An outpatient study in ENT (otorhinolaryngology) emergencies at a general hospital. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 1995 Jul-Aug;46(4):298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granick MS, Obeiter RD. Patient profile of an otolaryngologic emergency department. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1983 Aug 19;250(7):933–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bleach NR, Williamson PA, Mady SM. Emergency workload in otolaryngology. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1994 Sep;76(5):335–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozimek A, Miles D. Stata utilities for geocoding and generating travel time and travel distance information. The Stata Journal. 2011;11(1):106–119. [Google Scholar]

- 18. [Accessed November 22, 2013];Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epi Info version 7.1.3. http://www.cdc.gov.

- 19.Billings J, Parikh N, Mijanovich T. Emergency Department Use in New York City: A Survey of Bronx Patients. The Commonwealth Fund. 2000 Nov; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Billings J, Parikh N, Mijanovich T. Emergency room use: The New York Story. The Commonwealth Fund. 2000 Oct; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hijano R, Hernandez A, Martinez-Arias A, Homs I, Navarrete ML. Epidemiological study of emergency services at a tertiary care center. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2009 Jan-Feb;60(1):32–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alkon C. ENT Today. Vol January: Wiley; 2013. Urgent care centers may not adequately treat complex sinus issues. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellermann AL, Hsia RY, Yeh C, Morganti KG. Emergency care: then, now, and next. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013 Dec;32(12):2069–2074. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao MB, Lerro C, Gross CP. The shortage of on-call surgical specialist coverage: a national survey of emergency department directors. Acad Emerg Med. 2010 Dec;17(12):1374–1382. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.