Abstract

Background

The transfer of responsibility for patient care across clinical specialties is a complex process. Published and anecdotal data suggest that referrals often fail to meet the needs of one or both parties and that patient focus can be lost during the process. Little is known about the Australian situation.

Methods

To obtain a more complete understanding of the referral process, including the nature of communication in an Australian context, we conducted semistructured interviews in a convenience sample of 25 volunteers. Two established strategies for analyzing qualitative data were used.

Results

All respondents considered the following information essential components of a referral: an account of the patient's current condition, a working diagnosis or problem statement and history of the presenting concern, key test results or tests awaiting results, a potential management plan, and any special characteristics of the patient. Respondents acknowledged implied, if not literal, power to accept or reject an emergency department (ED) referral and said the imbalance of power was reinforced when the ED physician was junior to the inpatient clinician. Respondents also noted that in addition to the predominant organizational culture, an independent culture is associated with specific shifts. Foremost among the nonclinical aspects of a referral considered to be important was the timeliness of the contact made to achieve the transition. Respondents also said the success of a referral depended on the speaking and listening abilities of all parties. The individual's motivation to accept or reject a referral can also have an impact on communication.

Conclusion

Respondents attributed the difficulty of negotiating the transfer of a patient's care across the ED and inpatient interface to three distinct factors: variations in the clinical information required, the culture of the organization and of the clinical team in which the transaction takes place, and the characteristics of the individuals involved in the process. Improving communication skills has the potential to improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: Emergency medicine, patient admission, patient handoff, referral and consultation

INTRODUCTION

The transfer of responsibility for patient care across clinical specialties is a complex process. Beach et al1 noted that, in part, this complexity is because of differing cultures, expectations, and pressures on the participants. In the emergency medicine context in Queensland, Australia, clinical referral is the procedure whereby patients assessed in the emergency department (ED) are transitioned to inpatient medical or surgical teams. Referrals occur mainly through verbal exchanges, usually via telephone, although face-to-face discussions are not uncommon. Published and anecdotal data suggest that referrals often fail to meet the needs of one or both parties1-5 and that patient focus can be lost during the process. Horwitz et al2 identified areas of particular vulnerability during the referral process, including the communications environment, workload, information technology, patient flow, and assignment of responsibilities. Communication errors are a leading cause of medical mistakes with the potential to compromise patient safety6 and diminish the efficacy of a referral. Apker et al5 suggest that in practice these transition exchanges are often characterized by one-way delivery of information, whereas, ideally, they should be a two-way process of communication. Resultant negative outcomes of poor or failed referrals include delays to patient admission and specialist care, interpersonal discord, and worsening of ED overcrowding. ED overcrowding is associated with poorer patient outcomes including patient mortality.3,4

A number of North American studies7-9 have looked at the mechanics of handoff, the American process whereby the ED and inpatient specialties both accept that the receiving team is assuming responsibility for the patient. Beach et al1 recommend that the handoff process should include 7 components: a report on the patient's current clinical condition, a working problem statement, commentary on patient history and any abnormalities, a brief summary of the patient's course through the ED, results and/or analysis of key tests, a comment about pending data or tests not done, and any unusual circumstances such as language barriers.

Because little research has been done on the referral situation in Australia, the authors concluded that an investigation was warranted.6,10 With the permission of the Metro South Human Research Ethics Committee, a project steering committee was formed that determined a qualitative approach was best suited to this challenge as it would facilitate an in-depth understanding of both the circumstances and the people involved.

The study aimed to identify the essential components of a best-practice referral, the desirable and undesirable features of current practice, and strategies to improve practice.

METHODS

Design

This qualitative study design was founded on phenomenologic principles with the goal of understanding individual participants' lived experiences and the behavioral, emotional, and social meanings that these experiences have for emergency medicine physicians and inpatient medical and surgical teams. The technique considered most appropriate to meet the study's aims was the semistructured interview.

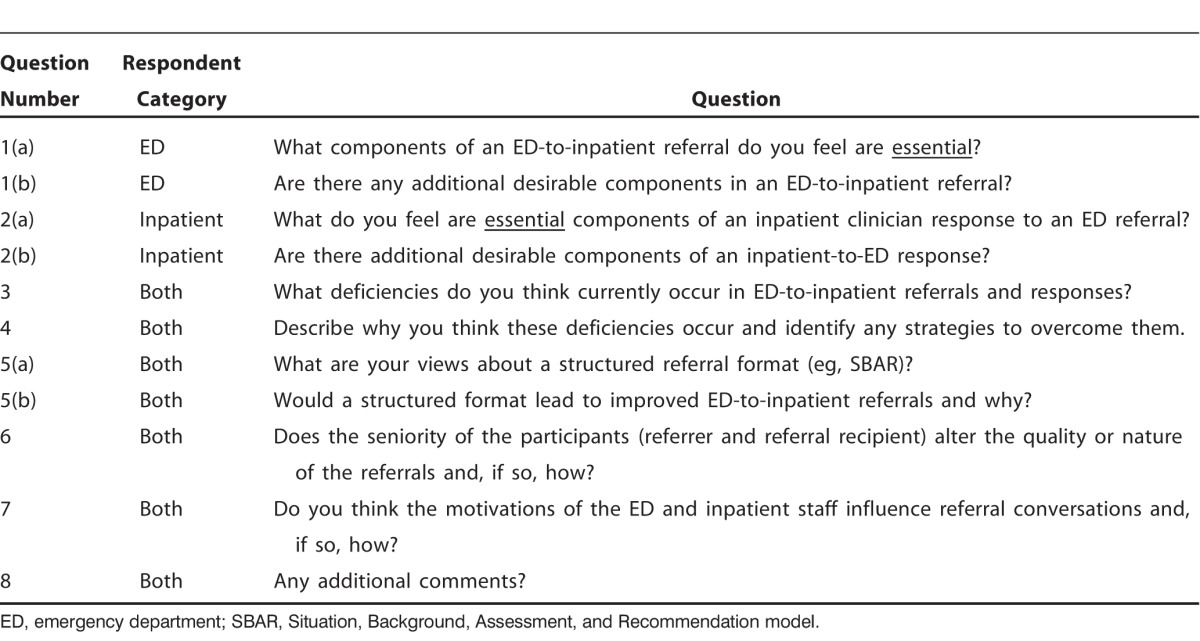

The semistructured interview guide used for this purpose was developed and pilot tested by the study steering committee (Table). In addition, demographic data were obtained from all participants, including occupational level (eg, consultant or specialist trainee), professional discipline (eg, surgeon), respondent year of graduation, and sex.

Table.

Semistructured Interview Guide

Recruitment

The principal investigator made a formal presentation at each of the departments' staff meetings informing the groups about the study, advising that interviews would be conducted by an independent investigator, assuring anonymity to encourage frank exchanges, and inviting staff to participate. Follow-up emails reinforced the invitation. Written consent was obtained from the volunteers at the time of the audio-recorded interviews. Interviews lasted 30-60 minutes, depending on the loquacity of the participant.

Data Analysis

All interviews were transcribed in accordance with qualitative research convention. The independent researcher read each transcript to obtain a preliminary understanding of the material and subsequently reread the transcript to identify key themes and concepts.

Two established strategies for analyzing qualitative data were used. Owen's11 criteria of repetition, recurrence, and forcefulness for identifying themes were used to aid thematic classification. These criteria identify ideas of particular importance to participants: recurrence, multiple descriptions with the same meaning; repetition, multiple use of the same wording; and forcefulness, nonverbal behavior evident in the tapes, such as pitch and volume. The 32-item checklist Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) by Tong et al12 further guided the interpretation. COREQ is a three-domain tool that addresses research team and reflexivity, study design and domain, and analysis and findings.

To achieve greater conceptual cohesion, results and preliminary analyses were circulated to the steering committee with links made between categories and subcategories. Responses from the committee members were incorporated into the final analysis.

RESULTS

A convenience sample of 25 volunteers participated: 12 from the ED, 7 from the Division of Medicine (DOM), and 6 from the Division of Surgery (DOS). In each division, at least 2 consultants and a minimum of 1 general trainee were interviewed. The number of advanced trainees varied. The years since graduation ranged more widely among DOM representatives (1979-2010) compared with the ED and DOS (1998-2010). More males than females were in the DOM and DOS samples compared with the ED where the numbers were equal.

Three themes emerged from the analysis. Similar to the Beach et al1 recommendations, the clinical status of the patient and his/her ED journey predominated. Two other aspects of the perceived success of an interdisciplinary transition were also influential: the culture of the organization and the personal features of the participating physicians.

The Patient

All respondents considered reports on the clinical condition of the patient a fundamental component of any referral. The required detail varied substantially between occupational categories and even within subspecialties. However, the following information was considered essential: an account of the patient's current condition, a working diagnosis or problem statement and history of presenting concern, key test results or tests awaiting results, a potential management plan, and any special characteristics of the patient, such as being a resident of an aged care facility.

Another aspect of this theme was the merit of a formal referral structure, such as the Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) model for building the clinical report. Unlike the findings of an American study,1 most Queensland respondents from all departments (ED, DOM, DOS) rejected the suggestion that a prescribed guideline should be used, stating that an obligatory document would add to the ED workload while not necessarily meeting the recipient's needs. Respondents from all occupations suggested that a model such as the SBAR would be more effective as a mental prompt or aide-mémoire.

One emergency medicine physician said:

When giving a referral, I actually use SBAR in my head, ticking off the various categories and waiting to hear if the reg[istrar] at the other end wants anything else under each of the headings. But I don't want the extra work of having to fill out forms or whatever. It just means more paperwork, even with the electronic records, and I don't think the extra documentation achieves much.

The Organization

In Australia, the operation of hospitals is hierarchical, with power vested most authoritatively in the occupants of positions at the top. The culture of the organization where the study was done reflected this management structure. Respondents from both inpatient categories (DOM and DOS) acknowledged their implied, if not literal, power to accept or reject an ED referral and said that the imbalance of power was reinforced when the ED physician was junior to the inpatient clinician. That is, two-way communication rarely characterized these exchanges. This perception was common to ED respondents, too, as one of them explained, “From my point of view, the referral was nothing like a two-way discussion; he just asked simple questions like, ‘Have you done [a specified] test?'” The power imbalance aspect was also significant in the theme of the individual as described in that section below.

When considering the impact of culture on the success of a referral, respondents also noted that in addition to the predominant organizational culture, a separate culture is associated with specific shifts. For example, fewer senior staff are rostered on the night shift of most inpatient teams. Therefore, accepting a new admission may be assigned a lower priority than attending to established patients. Irrespective of the hour when the referral is made, the duration of the shift is also important. For example, if the referral is presented toward the end of the shift, inpatient personnel may be reluctant to accept new patients and may transmit this reluctance in an abrupt manner, resulting in a diminished sense of collaboration.

The Individual

Foremost among the nonclinical aspects of a referral that every respondent considered important was the timeliness of the contact. According to each respondent, a convenient time for the referral was more likely to generate an enthusiastic response and encourage more friendly communication between the parties. However, respondents disagreed about notions of a convenient time. For some inpatient teams, “the earlier the better” applied; others preferred contact only after investigations had been completed and clinical results were available to report.

In addition to timeliness, respondents said the success of a referral depended on the speaking and listening abilities of all parties. Politeness of requests and responses, coupled with tone of voice and, where applicable, body language had the potential to make or break the exchange.

In Queensland, while junior ED staff receives instruction in the delivery of referrals, medical registrars do not have training in receiving referrals. Despite this lack of training, and somewhat unexpectedly, in answer to the question “What do you feel are essential components of an inpatient clinician response to an ED referral?” 1 surgeon and 2 physicians acknowledged limitations to the manner in which they responded to referrals. One respondent said, “I recognized that it could be helpful to raise additional questions that crossed my mind when patient A was being referred, but it takes time, and I prefer to do my own digging anyway.”

As noted earlier, the seniority of participants may also play a role. In some instances, less experienced ED staff attempting to refer patients to inpatient registrars reported feeling intimidated. One resident commented:

I was uncertain as to which team I should refer my patient with pneumonia: general medicine, infectious diseases, or the respiratory team. On approaching one team, I was told “this doesn't belong to us,” and the phone was hung up in my ear.

The respondent acknowledged that it was the recipient's prerogative to reject an admission but said she was none the wiser about where her patient should be admitted.

A female consultant in the ED reported similar treatment when she elected to make her own referral. This physician is soft spoken and sounds more youthful than many consultants. When she introduced herself to a medical registrar as a consultant in the ED and detailed her request, the registrar responded, “Can I speak to your senior?”

The individual's motivation to accept or reject a referral can also have an impact on communication. While it is widely acknowledged that the ED staff is usually keen to transfer patients out of the ED, inpatient teams are not always keen to accept particular patients. Several DOM and DOS respondents indicated that if the patient being referred has a condition of interest to the receiving team, such as Parkinson disease, the referral is much more likely to be accepted and with greater enthusiasm. Two-way communication is more likely to occur, and in a harmonious manner, if both parties perceive that they have something to gain from the outcome.

DISCUSSION

The 3 themes of greatest importance that emerged regarding essential characteristics of harmonious referrals were clinical aspects of the patient, the organizational culture, and the personal characteristics of all stakeholders. It should be noted that these themes and the 8 semistructured interview questions that generated them do not stand alone. Components of each likely interact with or have an impact on the others to a greater or lesser degree.

The absence of comments from any party about the need for the inpatient team to communicate basic information back to the referring physicians in the ED was a surprising finding. Any notion of mutual obligation or two-way communication seems absent, particularly in light of registrars' lack of training in the receipt of referrals.

Regarding recommendations for improvements to the current situation, the authors suggest that rules around essential feedback need to be established. As a component of their education responsibilities, professional colleges such as the Royal Australian College of Surgeons could be encouraged to train students in two-way communication. This training might include mutual principles and obligations to understand each other's needs, motivations, and responsibilities to ensure optimal patient safety, efficient patient care, and a more harmonious and professional interdisciplinary communication culture. In the context of training, consideration could also be given to the development of a template such as the SBAR, notwithstanding the low level of enthusiasm from our sample of respondents. Its success in America1 suggests that it is worthy of additional investigation.

At the practical level, two-way communication would allow both parties to better understand each specialty's respective viewpoints, pressures, and needs, leading to a more efficient and mutually satisfying resolution to this “predictable point of friction,” as described by one senior ED consultant reflecting on his experiences of past exchanges. Beach et al1 noted that negotiating this tension is a tradeoff between short- and long-term goals and is likely to be a key component of effective referral conversations. Incomplete one-way discussions that fail to identify and address the need for the exchange to be a two-way conversation are unlikely to lead to constructive referrals or efficient admission processing.

Changing inherent cultures is an important component of any process improvement. The rewards for ED staff resulting from improved admission efficiency, primarily the speedy transfer of patients out of the ED, are immediately apparent. For inpatient staff, they are less tangible. Hence, the challenge lies in ensuring that system benefits such as reduced access block in the hospital outweigh the immediate harms such as compromised patient safety caused by delay in delivery of care. External drivers may be most effective in initiating these changes. For example, the Australian National Emergency Access Target (NEAT) process that links funding to achieving a nominated percentage target of patients admitted within 4 hours has been a driver of a recent nationwide refocus on inpatient admission processes.13 The future of the NEAT scheme is uncertain; however, such policies are likely to be an important part of any program aimed at improving ED-to-inpatient admission efficiency. Until shared motivations are aligned, many referral conversations are likely to reflect ongoing cultural differences and continue to be a cause of friction for all parties.

Study Limitations

A limitation of this study is that it was conducted in a public teaching hospital that is required to train junior staff to become competent practitioners. Respondents from all occupational groups noted that the optimal referral is a peer-to-peer transaction because of its potential to be concise and brief thanks to the clinicians' years of practice and familiarity. Practicing in this manner is not possible in a training hospital. An additional limitation of this study is that the results may not directly transfer to the private system. Respondents noted that within the private system, referrals are almost always welcome and accepted with few reservations because of financial and professional reasons.

CONCLUSION

The referral of patients from EDs to inpatient teams in Queensland hospitals can be a fraught experience for some, or all, of the participants. This study examined the strengths and weaknesses of the current practice because the challenge of negotiating the transition of care can be so great that the focus on the patient is lost. Respondents in this study attributed the difficulty of negotiating the transfer of a patient's care across the ED/inpatient interface to 3 distinct factors: variations in the clinical information required, the culture of the organization and of the clinical teams in which the transfer takes place, and the characteristics of the individual participants in the process. Improving communication skills has the potential to improve patient outcomes. Such processes should also enhance clinician satisfaction and might lead to a reduction in patient harm associated with delayed transition through the ED.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge with gratitude the support of Dr Clair Sullivan, Deputy Chair of Medicine, Physician Training at Princess Alexandra Hospital, for her advice, guidance, and support during the implementation of this project. The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care and Medical Knowledge.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beach C, Cheung DS, Apker J, et al. Improving interunit transitions of care between emergency physicians and hospital medicine physicians: A conceptual approach. Acad Emerg Med. 2012 Oct;19(10):1188–1195. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horwitz LI, Meredith T, Schuur JD, Shah NR, Kulkarni RG, Jeng GY. Dropping the baton: a qualitative analysis of failures during the transition from emergency department to inpatient care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009 Jun;53(6):701–710.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sprivulis PC, Da Silva JA, Jacobs IG, Frazer AR, Jelinek GA. The association between hospital overcrowding and mortality among patients admitted via Western Australian emergency departments. Med J Aust. 2006 Mar 6;184(5):208–212. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson DB. Increase in patient mortality in 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med J Aust. 2006 Mar 6;184(5):213–216. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apker J, Mallak LA, Gibson SC. Communicating in the “gray zone”: perceptions about emergency physician hospitalists handoffs and patient safety. Acad Emerg Med. 2007 Oct;14(10):884–894. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brannen ML, Cameron KA, Adler M, Goodman D, Holl JL. Admission handoff communications: clinician's shared understanding of patient severity of illness and problems. J Patient Saf. 2009 Dec;5(4):237–242. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181c029e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun BD. Evaluating and improving the handoff process. J Emerg Nurs. 2012 Mar;8(12):151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maughan BC, Lei L, Cydulka RK. ED handoffs: observed practices and communication errors. Am J Emerg Med. 2011 Jun;29(5):502–511. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apker J, Mallak LA, Applegate EB, 3rd, et al. Exploring emergency physician-hospitalist handoff interactions. Development of the Handoff Communication Assessment. Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Feb;55(2):161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Australian Medical Association. Guidance on clinical handover for clinicians and managers. Australia: 2006. Safe handover: Safe patients. https://ama.com.au/sites/default/files/documents/Clinical_Handover_0.pdf. Published January 15, 2007. Accessed March 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owen W. Interpretive themes in relational communication. Q J Speech. 1984;70:274–287. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007 Dec;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geelhoed GC, de Klerk NH. Emergency department overcrowding, mortality and the 4-hour rule in Western Australia. Med J Aust. 2012 Feb;196:122–126. doi: 10.5694/mja11.11159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]