Abstract

Previous efforts to synthesize a cupric superoxide complex possessing a thioether donor have resulted in the formation of an end-on trans-peroxodicopper(II) species, [{(Ligand)CuII}2(μ-1,2-O22−)]2+. Redesign/modification of previous N3S tetradentate ligands has now allowed for the stabilization of the monomeric, superoxide product possessing a S(thioether)-ligation, [(DMAN3S)CuII(O2•−)]+ (2S), as characterized by UV-vis and resonance Raman (rR) spectroscopies. This complex mimics the putative CuII(O2•−) active species of the copper monooxygenase PHM and exhibits enhanced reactivity towards both O-H and C-H substrates in comparison to close analogues [(L)CuII(O2•−)]+, where L contains only nitrogen donor atoms. Cu-S(thioether) ligation with its weaker donor ability (relative to an N-donor) are demonstrated by comparisons to the chemistry of analogue compounds.

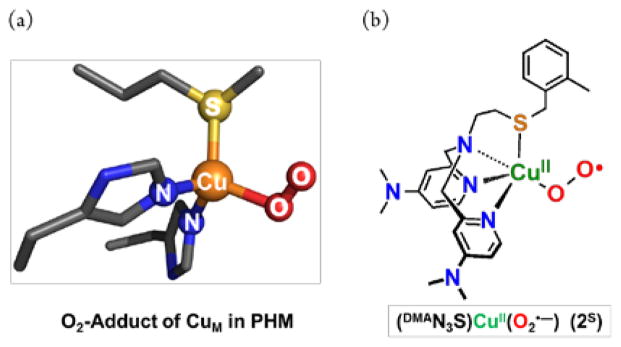

The copper monooxygenases peptidylglycine-α-hydroxylating monooxygenase (PHM) and dopamine-β-monooxygenase (DβM) possess a dicopper active site, but it is “noncoupled”; the two copper ions are about 11 Å apart.1 Extensive biochemical and biophysical research has shown that one copper ion (designated CuH or CuA) receives and passes electron reducing equivalents to the His2Met N2S(thioether) ligated CuM (or CuB) center, where O2 and substrate binding occur. Recent computational analyses2 lead to the hypothesis that an initial O2-adduct, a CuM centered cupric superoxide {CuII(O2•−)} moiety, forms from oxygenation of the fully reduced (CuI…CuI) enzyme. This species performs the H-atom abstraction of the peptide prohormone substrate (in PHM) leading to C–H hydroxylation and formation of the product hormone. Other reaction mechanisms suggesting other possible reactive intermediates being responsible for substrate C–H attack have been proposed.3 In support of the importance of the CuII(O2•−) reaction intermediate’s involvement, a crystal structure obtained by Amzel and co-workers in the presence of a substrate inhibitor, reveals dioxygen bound to CuM in an end-on fashion,1b as depicted in Scheme 1a.

Scheme 1.

Undoubtedly, the thioether ligand plays a critical role in determining the electronic structure and functions of CuM site leading to C-H bond activation.2 However, the precise role of Met coordination and the actual PHM reaction mechanism has yet to be fully elucidated.

Within the sub-field of copper-dioxygen synthetic bioinorganic chemistry, one long-standing goal has been to produce CuII(O2•−) species that can be studied in detail, and to this end several cupric-superoxo complexes have been reported with ligands containing either three or four N-atoms.4 In an attempt to mimic the active site donors of PHM and DβM, considerable effort has been devoted toward generating thioether containing tridentate or tetradentate ligands to study their CuI/O2 reactivity.5 In our own efforts we have been able to generate binuclear peroxodicopper complexes with S(thioether) ligation,6 but there has been no report of a mononuclear CuII(O2•−) species coordinated by a S(thioether) donor. Herein, for the first time we present the spectroscopic evidence and reactivity of the new mononuclear cupric superoxo complex, (DMAN3S)CuII(O2•−) (2S) (Scheme 1b) possessing thioether S-ligation that exhibits enhanced reactivity towards both O-H and C-H substrates.

This new ligand, DMAN3S,7 differs from our previously reported N3S ligands in two important ways. First, it possesses highly electron-rich dimethylamino (DMA)8 groups at the para position of the two pyridyl donors, a strategy from previously stabilized a mononuclear CuII(O2•−) complex containing N4 tripodal tetradentate ligand.4c,4h,9 Second, the thioether moiety is capped with a bulkier o-methyl benzyl substituent to slow dimerization relative to previous designs.6d Treatment of DMAN3S with [CuI(CH3CN)4]B(C6F5)4 in THF, followed by pentane addition leads to the isolation of bright yellow powders with formula [(DMAN3S)CuI]B(C6F5)4 (1).7 Single crystals could be grown from 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (MeTHF)/pentane at RT under Ar. As shown in Figure 1a, the cuprous complex is a four-coordinate monomer ligated by two pyridyl, one tertiary amine, and one thioether atom in a distorted pyramidal geometry providing a very open site for potential dioxygen binding. The Cu-S bond length in 1 (2.2327(5) Å) falls in the usual range (2.2 – 2.44 Å) for CuI–S(thioether) complexes.6 Many previously studied N3S(thioether)-CuI complexes form dimers in the solid state,6d and the incorporation of the larger o-methylbenzyl group may disfavor their formation.

Figure 1.

Displacement ellipsoid plots of the cations; (a) [(DMAN3S)CuI]+ (1) and (b) [(DMAN3S)CuII(H2O)(ClO4)]+ (3). Hydrogen atoms were removed for clarity.

Furthermore, the copper(II) complex [(DMAN3S)CuII (H2O)(ClO4)](ClO4) (3) (Figure 1b) was generated and structurally characterized.7 A slightly distorted octahedral coordination is observed. The thioether donor group is found in an axial position with Cu-S bond distance of 2.6974(6) Å. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurement on 3 reveals a standard axial spectrum of copper(II) complex.7

Bubbling O2 into a MeTHF solution of 1 at −135 °C led to the immediate formation of a new species (λmax = 425 nm) that rapidly (~50 s) converted to the thermodynamically more stable end-on trans-peroxodicopper(II) species [{(DMAN3S)CuII}2 (μ-1,2-O22−)]2+ (2P) (Figure 2, top) exhibiting strong UV-vis absorptions at λmax = 534 (6500 M−1cm−1) and 604 (6600 M−1cm−1) nm (Figure 2, bottom) consistent with the feature of previously synthesized S(thioether)-ligated (μ-1,2-peroxo)CuII2.6 The formulation of 2P is confirmed by rR spectroscopy (νO–O = 821 cm−1, νCu–O = 547 cm−1).7 Although the initially formed species has a short lifetime, the characteristic λmax value of 425 nm and the transformation to a more stable (μ-1,2-peroxo)CuII2, strongly suggest it is the S-ligated cupric superoxo species [(DMAN3S)CuII(O2•−)]+ (2S).

Figure 2.

Low-temperature UV-vis absorption spectra of the reaction of 1 with O2 at −135 °C in MeTHF (0.2 mM). The super-oxo product 2S is observed immediately upon O2 addition (red) and converted to the peroxo 2P (t = 50 s, blue).

Interestingly, when polar or potentially hydrogen-bonding solvents such as acetone, ethanol, methanol, or trifluoroethanol (TFE) are mixed with MeTHF, [(DMAN3S)CuII–OO•−]+ (2S) is much more persistent than is found in MeTHF only (Figure 3a; λmax = 418, 605, 743 nm). There appears to be a shift of the equilibrium constant to the mononuclear superoxide over the binuclear trans-peroxo complex. This result could be due to the formation of a hydrogen bond between an O-atom of the superoxide ligand and the TFE solvent, as observed in a ‘classical’ cobalt(III)-superoxo complex with TFE.10

Figure 3.

(a) Low-temperature (−135 °C) UV-vis absorption spectrum of 2S (containing ~11% 2P, λmax = 526 nm, ε = 6500)12 as recorded ~40 s after bubbling O2 into a MeTHF:TFE (4:1) solution of 1 (0.098 mM), and (b) rR spectra of frozen 2S (0.62 mM, λex = 413 nm, 77 K) in MeTHF:TFE (4:1).7

The rR spectra of 2S (λex = 413 nm) reveal two dioxygen isotope sensitive vibrations (Figure 3b). An O–O stretch is observed at 1117 cm−1 which shifts to 1056 cm−1 upon 18O2 substitution (Δ18O2 = −61 cm−1) and a Cu–O stretch at 460 cm−1 (Δ18O2 = −20 cm−1). The energy and isotope shifts of these vibrations confirm the assignment of 2S as an end-on superoxide species. In fact, these parameters closely match those for previously described cupric-superoxo complexes with tripodal tetradentate N4 ligands (DMAtmpa and DMMtmpa), (Table 1) both having νO–O = 1121 cm −1.4c,4h The species 2S is assigned as having an S = 1 (triplet) ground state by EPR spectroscopy.7,11

Table 1.

Comparison of LCuII/LCuI Redox Potentials and Reactivity of Derived [(L)CuII(O2•−)]+ Complexes.

| DMAtmpa4c | DMMtmpa4h | DMAN3S | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| p-OMe-DTBP a | No b | No b | Yes |

| AcrH2 a | No b | No b | Yes |

| E1/2, mV c | −700 | −570 | −470 |

Reaction comparisons of [(L)CuII(O2•−)]+ complexes (MeTHF:TFE (4:1) at −135 °C) toward substrates.

Reactions do occur, but only above −100 °C,

E1/2 (vs Fc+/Fc) [(L)CuII(solvent)](ClO4)2 complexes as determined by cyclic voltammetry.7

In MeTHF:TFE (4:1 v:v), an approximately 4:1 (mol/mol) equilibrium mixture of (2S)/(2P)12 forms within ~150 s following oxygenation of [(DMAN3S)CuI]+ (1) at −135 °C. This mixture shows minimal decomposition over an hour and thus, we could carry out reactivity studies of 2S with the O–H and C–H substrates; 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methoxyphenol (p-OMe-DTBP) and N-methyl-9,10-dihydroacridine (AcrH2). Pseudo first-order kinetic behavior was observed upon addition of p-OMe-DTBP (with t1/2 = 3 min) or AcrH2 (t1/2 = 2 min) as monitored by the disappearance of the 418 nm UV-vis band of 2S. Following workup at RT the products were analyzed as 2,6-di-tert-butyl-1,4-benzoquinone and 10-methyl-9-acridone, respectively.7 Independent observations demonstrate that the complex 2P is unreactive toward these substrates. Warming up the 2S solution does not lead to sulfur oxygenation which occurs by bis(μ-oxo)CuIII2 species.6d

To assess the effect of the thioether donor in 2S, we compared the reactivity of (L)CuII(O2•−) complexes (L = DMAtmpa or DMMtmpa) toward the same substrates.4c,4h Notably, both cupric superoxide complexes showed no reactivity under identical conditions (Table 1), although they do react above −100 °C. Thus, 2S with S(thioether)-ligation is more reactive than the closely related N4 superoxide compounds. The difference in reactivity is rationalized by the different donor strengths of the corresponding ligands. The substitution of a S(thioether) for a N(pyridine) donor decreases the ligand field strength, consistent with the CuII/I redox potentials for the separately isolated CuII complexes in which thioether coordination raises the reduction potential by 230 mV (Table 1).7 As a result, we hypothesize that 2S is more electrophilic and hence better able to accept an H-atom from either an O–H or C–H substrate, as compared to the N4 complexes.

The influence of the Cu–S interaction on the oxygenated products was further probed by comparing Cu/O2 species with different donor atoms binding Cu. Three structurally analogous ligands were synthesized replacing the sulfur site with carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen (Scheme 2).7 The isolated CuI complex with tridentate DMAN3 ligand exhibits a distinctive 382 nm absorption band7 upon O2 addition at −135 °C in MeTHF. This absorption spectrum is consistent with a bis(μ-oxo)CuIII2 complex, which is known for many other products from low-temperature oxygenation of CuI-N3 precursors.6d,14 Under identical reaction conditions, oxygenation of the CuI(DMAN3O), possessing three N-donors and an ether O-atom, leads to the initial formation of a (μ-1,2-peroxo)CuII2 which rapidly (~ 1 min) converts to a bis(μ-oxo)CuIII2 species with very similar UV-vis spectrum as for the case with DMAN3.6d,15 Thus, as seen before,6d,16 the oxygen atom of the ether arm in DMAN3O has an extremely weak to non-existent interaction with the copper ion in the oxygenated product. We find that for CuI(DMAN4) in MeTHF (Scheme 2c), both CuII–superoxo and (μ-1,2-peroxo)CuII2 complexes are generated7 as in the case of DMAN3S. This strongly suggests that the S(thioether)-atom donor of DMAN3S ligand is coordinated in both CuII–superoxo/μ-1,2-peroxo complexes, 2S and 2P. If it were not, a bis(μ-oxo)CuIII2 complex would prominently form.17

Scheme 2.

Oxygenated products of ligand-CuI complexes.13

In summary, [(DMAN3S)CuII(O2•−)]+ (2S) is the first reported example of a cupric superoxo species supported by a S(thioether) donor. This advance allowed us to determine that a superoxide species from an N3S donor was more reactive towards O–H and C–H bonds than the corresponding N4 complex. These results indicate that one role of the Met ligand in PHM and DβM is to activate the superoxide species for reaction by increasing their electrophilicity. The synthesis of this species will also allow us to further consider the role of thioether ligation on critical downstream O2-reduced (and protonated) derivatives, such as CuII-hydroperoxo and to perform detailed kinetic analysis of the preliminary reactivity study presented here.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support of this research from the National Institutes of Health (GM28962 to K.D.K., DK31450 to E.I.S., and Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F32-GM105288 to R.E.C.).

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Details concerning X-ray crystallography analyses including cif files, NMR, UV-vis, and rR spectroscopies, cyclic voltammetry, ESI mass spectrometry, and procedures for carrying out the reactivity studies. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Klinman JP. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2541–2561. doi: 10.1021/cr950047g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Prigge ST, Eipper B, Mains R, Amzel LM. Science. 2004;304:864–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1094583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Klinman JP. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3013–3016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Solomon EI, Heppner DE, Johnston EM, Ginsbach JW, Cirera J, Qayyum M, Kieber-Emmons MT, Kjaergaard CH, Hadt RG, Tian L. Chem Rev. 2014;114:3659–3853. doi: 10.1021/cr400327t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Chen P, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4991–5000. doi: 10.1021/ja031564g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen P, Bell J, Eipper BA, Solomon EI. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5735–5747. doi: 10.1021/bi0362830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Crespo A, Marti MA, Roitberg AE, Amzel LM, Estrin DA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12817. doi: 10.1021/ja062876x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yoshizawa K, Kihara N, Kamachi T, Shiota Y. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:3034. doi: 10.1021/ic0521168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Abad E, Rommel JB, Kaestner J. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:13726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.558494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Fujisawa K, Tanaka M, Morooka Y, Kitajima N. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:12079–12080. [Google Scholar]; (b) Würtele C, Gaoutchenova E, Harms K, Holthausen MC, Sundermeyer J, Schindler S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:3867–3869. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Maiti D, Fry HC, Woertink JS, Vance MA, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:264–265. doi: 10.1021/ja067411l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kunishita A, Kubo M, Sugimoto H, Ogura T, Sato K, Takui T, Itoh S. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2788–2789. doi: 10.1021/ja809464e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Donoghue PJ, Gupta AK, Boyce DW, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15869–15871. doi: 10.1021/ja106244k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Peterson RL, Himes RA, Kotani H, Suenobu T, Tian L, Siegler MA, Solomon EI, Fukuzumi S, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1702–1705. doi: 10.1021/ja110466q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Pirovano P, Magherusan AM, McGlynn C, Ure A, Lynes A, McDonald AR. Angew Chem A Intl Ed. 2014;53:5946–5950. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Lee JY, Peterson RL, Ohkubo K, Garcia-Bosch I, Himes RA, Woertink J, Moore CD, Solomon EI, Fukuzumi S, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9925–9937. doi: 10.1021/ja503105b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Kodera M, Kita T, Miura I, Nakayama N, Kawata T, Kano K, Hirota S. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7715–7716. doi: 10.1021/ja010689n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhou L, Nicholas KM. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:4356–4367. doi: 10.1021/ic800007t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Aboelella NW, Gherman BF, Hill LMR, York JT, Holm N, Young VG, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3445–3458. doi: 10.1021/ja057745v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Martínez-Alanis PR, Sánchez Eguía BN, Ugalde-Saldívar VM, Regla I, Demare P, Aullón G, Castillo I. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:6067–6079. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hoppe T, Josephs P, Kempf N, Wölper C, Schindler S, Neuba A, Henkel G. Z Anorg Allg Chem. 2013;639:1504–1511. [Google Scholar]; (f) Tano T, Mieda K, Sugimoto H, Ogura T, Itoh S. Dalton T. 2014;43:4871–4877. doi: 10.1039/c3dt52952e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Hatcher LQ, Lee DH, Vance MA, Milligan AE, Sarangi R, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:10055. doi: 10.1021/ic061813c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee Y, Lee D-H, Park GY, Lucas HR, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Kieber-Emmons MT, Vance MA, Milligan AE, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:8873. doi: 10.1021/ic101041m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Park GY, Lee Y, Lee DH, Woertink JS, Sarjeant AAN, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. Chem Comm. 2010;46:91–93. doi: 10.1039/b918616f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kim S, Ginsbach JW, Billah AI, Siegler MA, Moore CD, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:8063. doi: 10.1021/ja502974c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.See Supporting Information.

- 8.Zhang CX, Kaderli S, Costas M, Kim E-i, Neuhold Y-M, Karlin KD, Zuberbühler AD. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:1807. doi: 10.1021/ic0205684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.We believe the increased stability comes about as a result of great rate (constant) for formation of a CuII(O2•−) complex, because of the ligand donor group, where the rate of reaction of CuII(O2•−) with a second ligand-CuI species is not as enhanced a reaction.

- 10.Drago RS, Cannady JP, Leslie KA. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:6014–6019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ginsbach JW, Peterson RL, Cowley RE, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:12872–12874. doi: 10.1021/ic402357u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The ratio or relative amount of superoxo complex 2S to 2P was determined by first finding and calculating the molar absorptivity (ε) for a solution of pure 2P in MeTHF at −135 °C. Note: as described, initial oxygenation of a solution of a known concentration of 1 gives the 2S/2P mixture but waiting 5 min leads to complete conversion to 2P.

- 13.See the SI for CV’s and redox potential values for the CuII/CuI complex couples for the DMAN3, DMAN3O, DMAN4 ligands.

- 14.(a) Mirica LM, Ottenwaelder X, Stack TDP. Chem Rev. 2004;104:1013–1045. doi: 10.1021/cr020632z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hatcher LQ, Karlin KD. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:669–683. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kieber-Emmons MT, Ginsbach JW, Wick PK, Lucas HR, Helton ME, Lucchese B, Suzuki M, Zuberbühler AD, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2014;53:4935. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lucas HR, Li L, Sarjeant AAN, Vance MA, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3230–3245. doi: 10.1021/ja807081d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.More direct confirmation of a Cu-S(thioether) bond such as by X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy, is not possible here, due to the short lifetime of 2S and the related fact that higher concentrations need only lead to transformation of 2S to 2P.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.