Abstract

In the classical form of α1-antitrypsin deficiency (ATD), aberrant intracellular accumulation of misfolded mutant α1-antitrypsin Z (ATZ) in hepatocytes causes hepatic damage by a gain-of-function, “proteotoxic” mechanism. While some ATD patients develop severe liver disease that necessitates liver transplantation, others with the same genetic defect completely escape this clinical phenotype. We investigated whether induced pluripotent stem cells (iPScs) from ATD individuals with or without severe liver disease could model these personalized variations in hepatic disease phenotypes. Patient-specific iPScs were generated from ATD patients and controls and differentiated into hepatocyte-like cells (iHeps) having many characteristics of hepatocytes. Pulse-chase and endoglycosidase H analysis demonstrate that the iHeps recapitulate the abnormal accumulation and processing of the ATZ molecule compared to the wild type AT molecule. Measurements of the fate of intracellular ATZ show a marked delay in the rate of ATZ degradation in iHeps from severe liver disease patients compared to those from no liver disease patients. Transmission electron microscopy showed dilated rER in iHeps from all individuals with ATD, not in controls, but globular inclusions that are partially covered with ribosomes were observed only in iHeps from individuals with severe liver disease.

Conclusion

These results provide definitive validation that iHeps model the individual disease phenotypes of ATD patients with more rapid degradation of misfolded ATZ and lack of globular inclusions in cells from patients who have escaped liver disease. The results support the concept that “proteostasis” mechanisms, such as intracellular degradation pathways, play a role in observed variations in clinical phenotype and show that iPScs can potentially be used to facilitate predictions of disease susceptibility for more precise and timely application of therapeutic strategies.

The classical form of α1-antitrypsin deficiency (ATD), homozygous for the PiZ allele, is a single gene defect that is associated with liver disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The protein affected, α1-antitrypsin (AT), is a secretory glycoprotein predominantly synthesized in hepatocytes and primarily designed to inhibit neutrophil elastase and several related neutrophil proteases. In individuals with ATD, the point mutation renders this protein prone to misfolding such that it accumulates in early compartments of the secretory pathway resulting in decreased levels of the protein in extracellular fluids.1–4 Lack of AT molecules to counteract neutrophil proteases is thought to be the primary mechanism for lung disease, a loss-of-function mechanism. In contrast, hepatic disease is caused by a gain-of-function mechanism attributable to the intracellular accumulation/“proteotoxicity” of mutant ATZ in hepatocytes.4

There is, however, a wide variability in incidence, severity and age of onset of ATD-mediated liver disease.5 While some affected homozygotes develop life-threatening liver disease, a considerable number never develop clinical symptoms and in some cases the liver disease is first recognizable at 50–65 years of age. These observations have led us to theorize that genetic and/or environmental modifiers play a critical role in determining susceptibility to liver disease and that putative modifiers6 of pathways for intracellular ATZ degradation would be attractive targets for newly identified drug therapies.7–9

Groundbreaking studies demonstrating that somatic cells can be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPScs)10–13 have created the opportunity to generate a variety of patient-specific somatic cell types including hepatocyte-like cells.14–17 Recent studies have demonstrated that iPSc-derived hepatocyte-like cells (iHeps) derived from patients with metabolic liver diseases, including ATD, could be utilized for disease modeling.17–22 Here, we expand on previous work to investigate whether patient-specific iHeps could be used to model personalized variations in the severity of liver disease among ATD patients and ultimately be used to identify patients at risk for severe disease and address the “modifier” theory.

Materials and Methods

Generation of iPScs

Reprogramming of hepatocytes and fibroblasts was done using three different techniques. For all methods, iPSc colonies were isolated 20–30 days after induction based on morphology. Reprogramming of hepatocytes and fibroblasts was initiated using the viPS™ lentiviral gene transfer kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) following the manufacturer’s instructions to ectopically express OCT3/4, NANOG, SOX2, LIN28, KLF4, and C-MYC. Plasmid-mediated reprogramming was done according to a previously described protocol23 with modifications. For each nucleofection, 1x106 fibroblasts were resuspended in 100 uL of the Amaxa™ NHDF Nucleofector™ kit (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) containing 3 ug of each of the four expression plasmids encoding OCT3/4 and p53 shRNA, SOX2 and KLF4, L-MYC and LIN28, and eGFP. Cells were nucleofected using the Amaxa™ Nucleofector™ II (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) and were plated in mTeSR1™ on hESc-qualified Matrigel™-coated plates. Reprogramming of fibroblasts using the excisable lentivirus cassette has been described.24 Briefly, 1x105 of plated fibroblasts were incubated in fibroblast media containing 5 ug/mL polybrene and the four factor hSTEMCCA-loxP lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection of 10. The transfection of iPSc colonies for the excision of viral sequences was performed using the HelaMONSTER® transfection reagent (Mirus Bio LLC, Madison, WI) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Differentiation of iPScs into iHeps

Directed differentiation of iPScs into iHeps was performed in vitro using a variation of the 4-step protocol described by Si-Tayeb.16 Briefly, iPScs were single-cell passaged onto growth factor reduced Matrigel™ (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and induced to differentiate into definitive endoderm cells by treatment with RPMI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1X B27 w/o insulin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 0.5X NEAA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 100 ng/mL activin A (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 10 ng/mL BMP4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and 20 ng/mL FGF2 (Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 2 days followed by treatment with RPMI, 1X B27 w/o insulin and 0.5X NEAA with 100 ng/mL activin A for 3 days at ambient O2/5% CO2. For hepatic specification, the cells were cultured in RPMI, 1X B27 w/insulin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 0.5X NEAA containing 20 ng/mL BMP4 and 10 ng/mL FGF2 for 5 days at 4% O2/5% CO2. For hepatic induction, the cells were treated with RPMI, 1X B27 w/insulin and 0.5X NEAA containing 20 ng/mL HGF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 5 days at 4% O2/5% CO2. For hepatic maturation, the cells were cultured for 5 days in HCM™ (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) without EGF and with 20 ng/mL oncostatin M (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at ambient O2/5% CO2.

Sandwich ELISA

Antibodies and their corresponding dilutions are listed in Supporting Table 1. ELISA for albumin was done using the Human Albumin ELISA Quantitation Set (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) according to manufacturer’s protocol using Immulon™ 4HBX flat bottom microtiter plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The reaction was developed for 15 minutes with 100 uL/well TMB substrate solution (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) and stopped with 100 uL/well 0.18 M H2SO4. HRP activity was measured in a Thermo-max microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at 450 nm. ELISA for AT was performed using the same protocol for albumin, except for the coating antibody, primary antibody, secondary antibody, and human AT standard (Athens Research and Technology, Athens, GA).

Immunofluorescent staining

Antibodies and their corresponding dilutions are listed in Supporting Table 1. For cytoplasmic staining, cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. For nuclear staining, cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 100% pre-chilled ethanol at −20°C overnight. Cells were washed with wash buffer (PBS, 0.1% BSA, and 0.1% TWEEN®) and then blocked and permeabilized in blocking buffer (PBS, 10% normal donkey or goat serum, 1% BSA, 0.1% TWEEN®, and 0.1% Triton X-100) for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were then stained with primary or conjugated antibodies in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. After washing, cells were stained with secondary antibodies for 1 hour in the dark at room temperature. For membrane staining, cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. Cells were blocked with blocking buffer (PBS and 3% BSA/5% donkey serum) for 2 hours at room temperature and stained with conjugated antibodies in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. Stained samples were then incubated for 1 minute in 1 ug/mL Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Samples were imaged on a Fluoview™ 1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Central Valley, PA). Confocal stacks were rendered using MetaMorph® Image analysis software (Molecular Dynamics, Piscataway, NJ). Surface reconstructions were performed using Imaris Image analysis software (Bitplane USA, South Windsor CT).

Transmission electron microscopy

For iHeps, cell monolayers were briefly washed with PBS, pH 7.4. Samples were fixed in situ with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature and washed three times with PBS. Samples were submitted to the University of Pittsburgh Center for Biologic Imaging for post-fixation with 1% osmium tetroxide and 1% potassium ferricyanide for 1 hour at room temperature. Samples were washed three times with PBS and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solution (30%, 50%, 70%, and 90% - 10 minutes each) and three 15-minute changes in fresh 100% ethanol. Infiltration was done with three 1-hour changes of epon. The last change of epon was removed and beam capsules filled with resin were inverted over relevant areas of the monolayers. The resin was allowed to polymerize overnight at 37°C and then for 48 hours at 60°C. Beam capsules and underlying cells were detached from the bottom of the petri dish and sectioned. For tissue samples, tissues were cut into 1mm3 blocks and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4 overnight and processed as for the cell cultures, except that tissue samples were further dehydrated in two 10-minute changes of propylene oxide. Samples were infiltrated with a 1:1 mix of propylene oxide and epon overnight and infiltrated with pure epon overnight at 4°C. Infiltration was continued with three 1-hour changes of epon. Samples were embedded in pure epon for 24 hours at 37°C and cured for 48 hours at 60°C. Image acquisition was done using either the JEM-1011 or the JEM-1400Plus transmission electron microscopes (Jeol, Peabody, MA) at 80kV fitted with a side mount AMT 2k digital camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, MA). The percentage of cells that contained abnormal globular inclusions was determined by morphometric analysis of electron micrographs of no LD1a iHeps (n=98 cells), no LD2 iHeps (n=103 cells), no LD3 iHeps (n=128 cells), severe LD1 iHeps (n=97 cells), and severe LD2 iHeps (n=111 cells).

Pulse-chase analysis and densitometry

Methods for biosynthetic labeling with 35S methionine, immunoprecipitation, SDS/PAGE fluorography, and densitometric analysis have been described.6 Briefly, iHeps were washed three with HBSS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and pulse-labeled with DMEM minus methionine and cysteine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with TRAN35S-LABEL™ metabolic labeling reagent (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) for 1 hour. The cells were then washed three times with HBSS and incubated in DMEM with methionine and cysteine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) without labeling reagent for several different time intervals to constitute the chase. The intracellular and extracellular fractions were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-hAT nephelometric serum (Diasorin, Stillwater, MN) and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/fluorography. All fluorograms were subjected to densitometric analysis using ImageJ software.25 The relative densitometric value of T0 is set at 100% and the remainder of the data set expressed as % of this value. Variations in rates of degradation and secretion within replicates and groups (wild type, severe LD, no LD) were within the range previously reported for pulse-chase analyses of this type.6,26

Endoglycosidase H and PNGase F digestion

Immunoprecipitates of pulse-chase fractions were boiled in Glycoprotein Denaturing Buffer (NEB, Ipswich, MA) for 10 minutes. For wild type cells, immunoprecipitates of the intracellular fraction at time 0 and 0.5 hours (IC 0 and IC 0.5) and extracellular fraction at time 4.0 hours (EC 4.0) were analyzed. For ATD cells, immunoprecipitates of the intracellular fraction at time 0 and 4.0 hours (IC 0 and IC 4.0) and extracellular fraction at time 4.0 hours (EC 4.0) were analyzed. Samples were centrifuged at 13200 rpm for 10 minutes. For endo H, supernatants were added to a reaction containing 1X G5 Reaction Buffer (NEB, Ipswich, MA), 1 mM PMSF (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), 10 uM pepstatin A (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), and 20 U/uL endo H (NEB, Ipswich, MA) and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. For PNGase F, supernatants were added to a reaction containing 1X G7 Reaction Buffer (NEB, Ipswich, MA), 1% NP-40 (NEB, Ipswich, MA), 1 mM PMSF, 10 uM pepstatin A, and 10 U/uL PNGase F (NEB, Ipswich, MA) and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Samples were analyzed by analyzed by SDS-PAGE/fluorography.

Statistics

All values are presented as mean ± s.d. For composite kinetic curves, significance was calculated using two-way repeated measures ANOVA (**p<0.005) followed by Bonferroni posttests at each time point (++p<0.01, +++p<0.001, ++++p<0.0001) analyzed through GraphPad Prism® (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Generation of iPSc-derived hepatocyte-like cells from ATD patients

We generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPScs) from a wild type control patient and homozygous PiZZ ATD patients with severe liver disease, requiring liver transplantation during childhood (hereinafter referred to as severe LD) and those with lung disease but no clinically overt liver disease (hereinafter referred to as no LD) (Supporting Table 2; Supporting Fig. 1A, B). DNA sequencing confirmed that the wild type iPScs have the PiMM genotype (G11940, Glu342) while the ATD iPScs carried the PiZZ genotype (G11940A, Glu342Lys) (Supporting Fig. 1C). Directed differentiation of iPScs into hepatocyte-like cells (iHeps) was done using a previously published protocol16 because of the presumed need for a homogenous population of iHeps. The differentiation was monitored through the expression of stage-specific markers (Supporting Fig. 2A, B). While the iHeps did not demonstrate the full array of mature hepatocyte function, they did express the hepatocyte markers AFP, albumin and ASGPR (Supporting Fig. 2C), exhibited ultrastructural features characteristic of primary hepatocytes, and secreted albumin at levels 35–50% of the amount secreted by primary hepatocytes (Supporting Fig. 3). Despite the use of different cell sources and reprogramming methods for generating iPScs, levels of secreted albumin and ASGPR and AFP marker expression were similar in all iHeps indicating equivalent degree of differentiation across all iPSc lines.

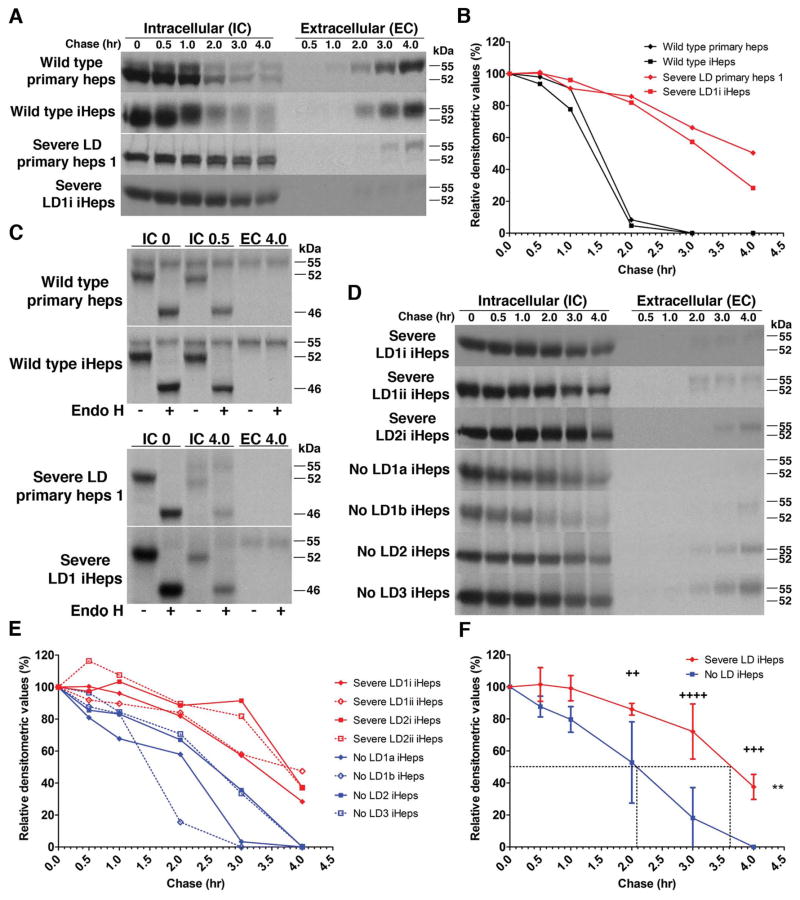

iHeps from ATD patients recapitulate the accumulation and processing of ATZ

We used pulse-chase radiolabeling to analyze the kinetics of ATZ processing and secretion in iHeps from severe LD patients as the most sophisticated and definitive strategy to determine whether these cells model the known cellular defect that characterizes ATD. In both wild type iHeps and primary hepatocyte controls, AT is synthesized as a 52-kDa polypeptide that quickly becomes converted to a 55-kDa polypeptide. AT disappears from the intracellular compartment between 1 and 2 hours, coincident with appearance of the 55-kDa polypeptide in the extracellular medium (Fig. 1A). In iHeps from severe LD patients, the 52-kDa ATZ polypeptide very slowly disappears from the intracellular compartment over the entire 4 hours of the chase period with minimal conversion to the 55-kDa polypeptide. A lesser amount of the 55-kDa ATZ polypeptide is detected in the extracellular fluid and it begins to appear only at the 3.0-hour time point (Fig. 1A). The fate of ATZ in iHeps from severe LD patients was identical to its fate in primary hepatocytes from severe LD patients (Fig. 1A). The half-time for the disappearance of AT from the intracellular compartment for wild type iHeps and primary hepatocyte controls was 1.4 ± 0.1 hours as compared to 3.6 ± 0.4 hours for the iHeps and primary hepatocytes from severe LD patients (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, analysis of the percentage of AT in the extracellular fluid at 3.0 and 4.0 hours of the chase period relative to the amount of AT in the intracellular compartment at time 0 revealed that iHeps and primary hepatocytes from severe LD patients have markedly reduced AT secretion compared to wild type iHeps and primary hepatocyte controls (Supporting Fig. 4). This was an important analysis because we found that the relative rate of secretion of AT from wild type iHeps and primary hepatocyte controls is lower than in model cell lines generated by gene transfer, such as the HeLa HTO/M cell line (Supporting Fig. 4), and human fibroblast cell lines6 as well as continuous cell lines, including human hepatoma HepG2 and Hep3B, and human monocytes in primary culture.26 This difference in rate of secretion of AT could therefore represent ‘leakiness’ in the previous model cell lines or lack of full differentiated function in iHeps and primary hepatocytes in culture. Nevertheless, each of these cell systems are models and the important result is the clear difference in secretion between AT and the misfolded variant ATZ in each system. Thus, we conclude from the investigations thus far that iHeps from patients with severe LD accurately model the intracellular accumulation and diminished secretion characteristic of the misfolded ATZ molecule.6, 26 Indeed, this is the first time that this type of sophisticated kinetic analysis with pulse-chase radiolabeling has been used to definitively and quantitatively show that iHeps faithfully model the basic defect of the classical form of ATD and to provide quantitative rate measurements for the fate of ATZ.

Figure 1.

ATD iHeps recapitulate the accumulation and processing of ATZ. (A) Pulse-chase labeling showing intracellular accumulation of AT in severe LD cells but not in wild type cells. (B) Kinetics of the disappearance of AT in severe LD and wild type cells. Values are band densities of IC fractions in (A) relative to IC signal at time 0. Effect of (C) endoglycosidase H digestion on AT in pulse-chase IC and EC fractions of cells at indicated timepoints. (−) mock digestion, (+) endo H digestion. (D) Pulse-chase labeling comparing the disappearance of intracellular AT in severe and no LD iHeps. Severe LD1i and LD1ii are replicates from the same iPSc line. No LD1a and no LD1b are different iPSc clones from the same patient. (E) Kinetics of the degradation of AT in severe and no LD iHeps. Values are band densities of IC fractions in (D) relative to IC signal at time 0. (F) Composite curves of (E) shown as mean ± s.d. Dashed lines represent the half-time for disappearance of intracellular AT. **p<0.005 (two-way repeated measures ANOVA), ++p<0.01, +++p<0.001, ++++p<0.0001 (Bonferroni posttests at each time point). Although densitometric values for the no LD iHeps appear to reach zero, the absolute values are <1% in E and F.

Next we used endoglycosidase H (endo H) as a biochemical assay to further characterize the fate of ATZ in the intracellular compartment. In wild type iHeps and primary hepatocyte controls, the 52-kDa AT polypeptide is an endo H-sensitive partially glycosylated intermediate and the 55-kDa polypeptide that is detected intracellularly and extracellularly is endo H-resistant. In iHeps and primary hepatocytes from severe LD patients, the 52-kDa ATZ polypeptide that accumulates is endo H-sensitive whereas the very small amount of 55-kDa polypeptide that can be detected is endo H-resistant (Fig. 1C). This indicates that the ATZ molecule that accumulates is a partially glycosylated intermediate and is predominantly localized to pre-Golgi compartments. This result is similar to what we observed using the HeLa HTO/M and HTO/Z cell line models (Supporting Fig. 5).

iHeps from ATD patients with no liver disease more efficiently degrade misfolded ATZ

Now having established that ATD iHeps model the known biochemical abnormalities associated with the misfolded ATZ molecule,6, 26, 27 we next investigated whether there is a difference in the fate of ATZ in severe LD and no LD iHeps by pulse-chase labeling (Fig. 1D). In severe LD iHeps, intracellular ATZ slowly disappeared with more than ~30% of radioactively labeled ATZ remaining after 4 hours. In no LD iHeps however, intracellular ATZ disappears more rapidly, beginning at the 2- and 3-hour time points with minimal radioactively labeled ATZ remaining at 4 hours (Fig. 1D, E). Intracellular ATZ disappeared slower in severe LD iHeps (p<0.005) with a half-time of 3.6 ± 0.1 hours compared to 2.2 ± 0.3 hours in no LD iHeps (Fig. 1F). Quantitative accounting for all of the radiolabeled ATZ showed that the more rapid disappearance of ATZ from the intracellular compartment in the no LD iHeps could not be explained by increased secretion in the extracellular compartment (Supporting Fig. 6) and is therefore entirely due to enhanced intracellular degradation. The validity of the modeling was apparent in several other ways. The kinetics of disappearance of ATZ was similar in iHeps from multiple iPSc clones from the same patient and in iHeps from unrelated PiZZ individuals that have the same liver disease phenotype (Fig. 1D, E). Thus, these results indicate that ATZ has a different fate in iHeps from ATD patients with liver disease with significantly slower intracellular degradation than in iHeps from ATD patients with no liver disease. Importantly, the kinetic measurements of ATZ degradation in iHeps reported here are further validated by the fact that similar rates of ATZ degradation were observed years ago in genetically engineered skin fibroblasts from ATD patients,6 a model system that lacked hepatocyte characteristics and proved unwieldy for long-term studies. The similarity in rates of degradation in these 2 different systems provides further evidence for the validity of the difference between severe LD and no LD patients and for the validity of the pulse-chase analytic method.

ATZ accumulates in the rER as well as in non-rER compartments of ATD iHeps

Having demonstrated that iHeps can model the fate of ATZ biochemically, we next examined the extent to which iHeps can model the disease morphologically. Early ultrastructural analysis of liver biopsies from ATD patients28, 29 as well as immunofluorescence studies of model cell lines transduced to express mutant ATZ30 have led to the conventional wisdom that misfolded ATZ accumulates in the ER. To determine the sites of ATZ accumulation in severe LD iHeps, we performed double label immunofluorescence for AT and the rough ER (rER) markers calnexin and calreticulin. AT staining co-localized with rER markers but several large areas of AT accumulation did not (Fig. 2A–D). The fact that none of the large areas of ATZ accumulation co-localized with the Golgi marker GM130 (Fig. 2E, F), together with the Endo H studies (Fig. 1C) indicate that ATZ predominantly localizes to pre-Golgi compartments. The co-localization of ATZ and rER markers varied within and among cells (Fig. 2G). Three-dimensional reconstruction of confocal image stacks from severe LD iHeps stained for AT and calnexin shows regions of ATZ accumulation that were enveloped by calnexin and others that were not. Some areas of calnexin-enclosed AT were also observed to be continuous with calnexin-free AT accumulation (Fig. 2H, I). Thus, our results also suggest that ATZ accumulates in the rER as well as in non-rER compartments.

Figure 2.

ATZ in severe LD iHeps accumulates in rER and in compartments that are devoid of calnexin, calreticulin, or GM130. Immunofluorescent staining of severe LD iHeps for AT and calnexin (A, B), calreticulin (C, D), or GM130 (E, F). A, C, E (600X), B, D, F (2000X). (G) Single stack image of severe LD iHeps stained for AT and calnexin. (H and I) 3D surface reconstruction of multiple stacks of images of AT/calnexin-stained severe LD iHeps with calnexin signal made partially transparent to reveal AT staining inside calnexin staining. Nuclei are stained blue.

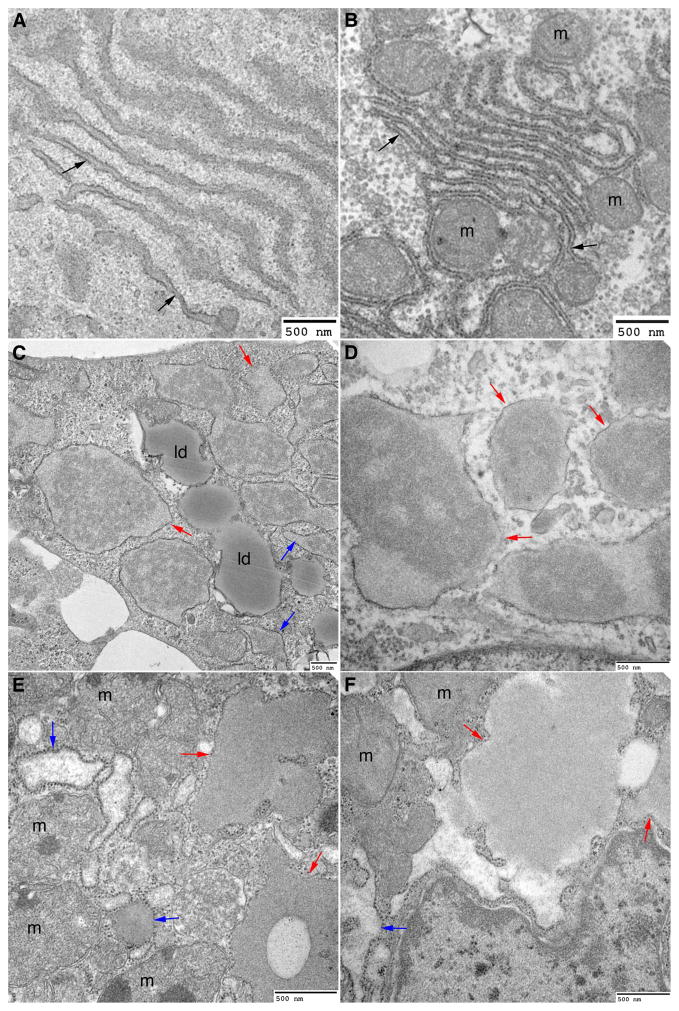

Next we analyzed the ultrastructure of iHeps from severe LD patients and we used liver biopsy specimens from severe LD patients for comparison. In contrast to wild type iHeps which displayed normal rER morphology similar to those seen in wild type liver sections (Fig. 3A, B), severe LD iHeps had markedly dilated rER as well as abnormal globular inclusions, large vesicular structures enveloping proteinaceous material and partially covered with ribosomes (Fig. 3C, D). Liver sections from ATD patients with severe LD had similar morphological characteristics (Fig. 3E, F).28 The globular inclusions are filled with granular material that, in some areas, appears electron-dense. In some cells, the globular inclusions are almost completely devoid of ribosomes but because of the single plane of the image it is not possible to exclude the presence of some ribosome-containing areas. These observations are consistent with the double immunofluorescence and three-dimensional reconstructions (Fig. 2H, I) showing accumulation of ATZ in calnexin-positive and calnexin-free structures. These globular inclusions that are calnexin-free could represent dilations of smooth ER, specialized sub-domains of the rER or a completely separate subcompartment as has been observed for some misfolded proteins.31 While some cells in severe LD iHeps had normal looking organelles, many cells that contained inclusions had obvious accumulation of lipid droplets, autophagosomes, abnormal mitochondrial structures and fragmented Golgi (Figs. 3C and 4A, C; Supporting Figs. 7–9), remarkably similar to what was seen in liver sections of ATD patients with severe LD.28 Thus, using detailed microscopic, ultramicroscopic as well as immunofluorescent analysis of iHeps from ATD patients for the first time, these results provide evidence that iHeps recapitulate the morphological characteristics seen in the liver of ATD patients with severe LD and establish iHeps as an ideal model for analysis of the biology of the misfolded ATZ molecule at subcellular as well as biochemical levels, particularly because these cells are hepatocytic.

Figure 3.

Severe LD iHeps and severe LD liver tissue sections exhibit dilated rER and globular inclusions that are partially covered with ribosomes. Electron micrograph of wild type iHeps (A), wild type liver tissue section (B), severe LD iHeps (C, D), and severe LD liver tissue section (E, F) showing normal rER (black arrows), dilated rER (blue arrows) and globular inclusions that are partially covered with ribosomes (red arrows). m: mitochondria, ld: lipid droplets.

Figure 4.

Severe LD iHeps and no LD iHeps exhibit dilated rER but only severe LD iHeps exhibit globular inclusions. Electron micrograph of severe LD iHeps (A–C) and no LD iHeps (D–F) showing normal rER (black arrows), dilated rER (blue arrows) and globular inclusions that are partially covered with ribosomes (red arrows). ld: lipid droplets, n: nucleus, m: mitochondria.

No LD iHeps lack intracellular inclusions that are the cellular hallmark of the disease

Because liver biopsies are not routinely performed on ATD patients with no symptomatic liver disease, the ultrastructure of hepatocytes in this group of patients has not been studied. We therefore used TEM to determine if there are ultrastructural differences between severe LD (Fig. 4A–C) and no LD iHeps (Fig. 4D–F). Although dilated rER was observed in iHeps from no LD patients, there was a remarkable absence of globular inclusions (Fig. 4D–F). Using quantitative morphometry, globular inclusions were observed in 26.59 ± 7% of iHeps from severe LD patients as compared to none of the iHeps from no LD patients. This suggests that the degradative response that leads to enhanced intracellular disposal of ATZ in no LD individuals, as shown by the pulse-chase results in Fig. 1D–F, might be sufficient to prevent this morphological hallmark of ATZ accumulation. Furthermore, this morphological difference could be used as a relatively straightforward diagnostic criterion to predict susceptibility to liver disease in individuals with ATD.

Discussion

Previous studies have described the generation of patient-derived iHeps for modeling ATD.17–20 This study takes the technology one step further by demonstrating that patient-derived iPScs can model the biochemical and morphological manifestations of a primary genetic defect and the modifiers that correlate with the clinical phenotype in individual patients.

Despite concerns that the use of different cell sources and reprogramming methods for generating iPScs might lead to variability in the differentiation potential of the derived cells, we found that the degree of hepatocyte differentiation was equivalent across all iPSc lines irrespective of these factors. More importantly, the kinetics of ATZ disposal and the ultrastructural features were similar in iHeps from different iPSc clones from the same patient and in iHeps from unrelated PiZZ individuals that have the same liver disease phenotype.

From a cell biological perspective, the results provide support for the concept that quality control “proteostasis” mechanisms, in this case intracellular degradation pathway(s), play a critical role in determining the severity of disease, presumably by affecting the degree of “proteotoxicity”.32 In terms of ATD, the current study supports a long-held hypothesis that variation in hepatic phenotype could be attributed at least in part to modifiers that target either intracellular degradation mechanisms or signaling pathways which facilitate adaptation of cells to accumulation of misfolded proteins.6 Although the studies reported here do not identify the specific genes that represent the putative modifiers, we now know that the modifiers, at least in the patients investigated here, are going to be within the intracellular degradation pathways or regulators of those pathways. This conclusion is also important because it is possible, if not probable, that variation in the liver phenotype among ATD patients is due to genetic or environmental modifiers that lead to hepatocyte dysfunction completely independent of an effect on the fate of misfolded ATZ (e.g. steatosis, iron overload). The results also indicate that iHeps will provide a valid system for identifying the mechanism by which putative modifiers affect the fate of ATZ.

The fact that the hallmark intracellular inclusions are not present in iHeps from ATD patients apparently “protected” from liver disease is a major advance for clinical management of this disease. This characteristic may now be used to predict which individuals are susceptible to “proteotoxic” consequences and liver disease well before liver disease progresses to end-stage, necessitating liver transplantation. By showing that patients are apparently susceptible to liver disease because their endogenous intracellular degradation mechanisms are not as efficient as in “protected” hosts, the results provide even more optimism for the recently identified therapeutic strategies utilizing drugs such as carbamazepine and fluphenazine, which enhance autophagic degradation of ATZ.7–9

In these studies we used iHeps from ATD patients with severe liver disease during the childhood years. It will now be interesting to determine if differences in kinetic characteristics or morphology can be ascertained in iHeps representing the other forms of ATD liver disease, with onset in adolescence or adult years, or with isolated hepatocellular carcinoma. It will also be important to determine if the kinetic and morphological characteristics are stable when collected from single individuals serially over time. We suspect that these characteristics will be stable over time because of the similarities in mean rate of intracellular degradation for each group when investigated in the fibroblast cell lines previously6 and iHeps in this report and because the iHeps from ATD patients with no liver disease which had a relatively increased rate of intracellular degradation were established from these patients at adult ages of 42–67 years. If not stable we would have expected this rate of degradation to decrease with age. Finally, it will be interesting to determine if biochemical or morphological characteristics of iPScs can be used for other misfolded protein disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, to identify/predict different clinical severities. In either case, the results of this report take us one step closer to the dream of truly personalized, precision medicine for genetically-determined diseases by demonstrating that patient-derived pluripotent stem cells can model individualized variations in clinical severity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH Grant PO1 DK096990, DOD Grant W81XWH-09-1-0658, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC RAC Pre-doctoral Fellowship, and NYSTEM Grant C026440.

Abbreviations

- AFP

alpha fetoprotein

- ASGPR

asialoglycoprotein receptor

- AT

α1-antitrypsin

- ATD

classical α1-antitrypsin deficiency

- ATZ

mutant α1-antitrypsin Z

- cDNA

complementary deoxyribonucleic acid

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- iHeps

iPSc-derived hepatocyte-like cells

- iPScs

induced pluripotent stem cells

- LD

liver disease

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- rER

rough ER

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Author Contributions E.N.T. designed and performed most of the experiments and collected and analyzed most of the data reported. I.J.F., D.H.P., A.S., D.B.S., S.C.S., J.R.C., C.A.F., A.A.W., and D.N.K. provided guidance throughout. B.H., P.H., W.W., and M.N. performed some experiments and collected data. S.C. and D.B.S performed most of the imaging and image analysis. C.A.F., A.A.W., and D.N.K. provided some of the cells for analysis. E.N.T., I.J.F, and D.H.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed, critiqued and offered comments to the text.

Additional Supporting Information is available for this article.

References

- 1.Chan S, Rees D. Molecular basis for the alpha1-protease inhibitor deficiency. Nature. 1975;255:240–241. doi: 10.1038/255240a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrell R, Jeppsson J, Laurell C, Brennan S, Owen M, Vaughan L, Boswell D. Structure and variation of human alpha 1-antitrypsin. Nature. 1982;298:329–334. doi: 10.1038/298329a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perlmutter D, Cole F, Kilbridge P, Rossing T, Colten H. Expression of the alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor gene in human monocytes and macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:795–799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perlmutter DH, Silverman GA. Hepatic fibrosis and carcinogenesis in alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency: a prototype for chronic tissue damage in gain-of-function disorders. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson D, Teckman J, Di Bisceglie A, Brenner D. Diagnosis and management of patients with α1-antitrypsin (A1AT) deficiency. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:575–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Y, Whitman I, Molmenti E, Moore K, Hippenmeyer P, Perlmutter D. A lag in intracellular degradation of mutant alpha 1-antitrypsin correlates with the liver disease phenotype in homozygous PiZZ alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9014–9018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hidvegi T, Ewing M, Hale P, Dippold C, Beckett C, Kemp C, Maurice N, et al. An autophagy-enhancing drug promotes degradation of mutant alpha1-antitrypsin Z and reduces hepatic fibrosis. Science. 2010;329:229–232. doi: 10.1126/science.1190354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Pak SC, O’Reilly LP, Benson JA, Wang Y, Hidvegi T, Hale P, et al. Fluphenazine reduces proteotoxicity in C. elegans and mammalian models of alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gosai SJ, Kwak JH, Luke CJ, Long OS, King DE, Kovatch KJ, Johnston PA, et al. Automated high-content live animal drug screening using C. elegans expressing the aggregation prone serpin α1-antitrypsin Z. PloS one. 2009:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Okita K, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu J, Hu K, Smuga-Otto K, Tian S, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science. 2009;324:797–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1172482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basma H, Soto-Gutierrez A, Yannam GR, Liu L, Ito R, Yamamoto T, Ellis E, et al. Differentiation and transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:990–999. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song Z, Cai J, Liu Y, Zhao D, Yong J, Duo S, Song X, et al. Efficient generation of hepatocyte-like cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Res. 2009;19:1233–1242. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Si-Tayeb K, Noto FK, Nagaoka M, Li J, Battle MA, Duris C, North PE, et al. Highly efficient generation of human hepatocyte-like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Hepatology. 2010;51:297–305. doi: 10.1002/hep.23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rashid ST, Corbineau S, Hannan N, Marciniak SJ, Miranda E, Alexander G, Huang-Doran I, et al. Modeling inherited metabolic disorders of the liver using human induced pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3127–3136. doi: 10.1172/JCI43122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yusa K, Rashid ST, Strick-Marchand H, Varela I, Liu P-QQ, Paschon DE, Miranda E, et al. Targeted gene correction of α1-antitrypsin deficiency in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;478:391–394. doi: 10.1038/nature10424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi SM, Kim Y, Shim JS, Park JT, Wang R-HH, Leach SD, Liu JO, et al. Efficient drug screening and gene correction for treating liver disease using patient-specific stem cells. Hepatology. 2013;57:2458–2468. doi: 10.1002/hep.26237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eggenschwiler R, Loya K, Wu G, Sharma AD, Sgodda M, Zychlinski D, Herr C, et al. Sustained knockdown of a disease-causing gene in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells using lentiviral vector-based gene therapy. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2:641–654. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cayo MA, Cai J, DeLaForest A, Noto FK, Nagaoka M, Clark BS, Collery RF, et al. JD induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocytes faithfully recapitulate the pathophysiology of familial hypercholesterolemia. Hepatology. 2012;56:2163–2171. doi: 10.1002/hep.25871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung A, Nah SK, Reid W, Ebata A, Koch CM, Monti S, Genereux JC, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell modeling of multisystemic, hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. Stem cell reports. 2012;1:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okita K, Matsumura Y, Sato Y, Okada A, Morizane A, Okamoto S, Hong H, et al. A more efficient method to generate integration-free human iPS cells. Nat methods. 2011;8:409–412. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Somers A, Jean J-C, Sommer C, Omari A, Ford C, Mills J, Ying L, et al. Generation of transgene-free lung disease-specific human induced pluripotent stem cells using a single excisable lentiviral stem cell cassette. Stem cells. 2010;28:1728–1740. doi: 10.1002/stem.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider C, Rasband W, Eliceiri K. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perlmutter DH, Kay RM, Cole FS, Rossing TH, Van Thiel D, Colten HR. The cellular defect in alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor (alpha 1-PI) deficiency is expressed in human monocytes and in Xenopus oocytes injected with human liver mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:6918–6921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.20.6918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teckman JH, Burrows J, Hidvegi T, Schmidt B, Hale PD, Perlmutter DH. The proteasome participates in degradation of mutant alpha 1-antitrypsin Z in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatoma-derived hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44865–44872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yunis E, Agostini R, Glew R. Fine structural observations of the liver in alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Pathol. 1976;82:265–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hultcrantz R, Mengarelli S. Ultrastructural liver pathology in patients with minimal liver disease and alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency: a comparison between heterozygous and homozygous patients. Hepatology. 1983;4:937–945. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miranda E, Pérez J, Ekeowa UI, Hadzic N, Kalsheker N, Gooptu B, Portmann B, et al. A novel monoclonal antibody to characterize pathogenic polymers in liver disease associated with alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Hepatology. 2010;52:1078–1088. doi: 10.1002/hep.23760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolff S, Weissman J, Dillin A. Differential scales of protein quality control. Cell. 2014;157:52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balch W, Morimoto R, Dillin A, Kelly J. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.