Abstract

Purpose:

Imaging of midbrain nuclei using T2- or T2*-weighted MRI often entails long echo time, leading to long scan time. In this study, an inverse double-echo steady-state (iDESS) technique is proposed for efficiently depicting midbrain nuclei.

Methods:

Thirteen healthy subjects participated in this study. iDESS was performed along with two sets of T2*-weighted spoiled gradient-echo images (SPGR1, with scan time identical to iDESS and SPGR2, using clinical scanning parameters as a reference standard) for comparison. Generation of iDESS composite images combining two echo signals was optimized for maximal contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) between the red nuclei and surrounding tissues. Signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) were calculated from the occipital lobe. Comparison was also made using phase-enhanced images as in standard susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI).

Results:

The iDESS images present significantly higher SNR efficiency (171.3) than SPGR1 (158.7, p = 0.013) and SPGR2 (95.5, p < 10−8). iDESS CNR efficiency (19.2) is also significantly greater than SPGR1 (6.9, p < 10−6) and SPGR2 (14.3, p = 0.0016). Compared with DESS, iDESS provides further advantage on enhanced phase information and hence improved contrast on SWI-processed images.

Conclusions:

iDESS efficiently depicts midbrain nuclei with improved CNR efficiency, increased SNR efficiency, and reduced scan time and is less prone to susceptibility signal loss from air-tissue interfaces.

Keywords: midbrain nuclei, iron deposition, susceptibility contrast, double-echo steady-state, susceptibility-weighted imaging

1. INTRODUCTION

Midbrain nuclei are known to be associated with neurodegenerative diseases that cause movement disorders. For example, in Parkinson’s disease, hypokinesias (such as bradykinesia, freezing, and rigidity) occur due to the involvement of pathological changes in substantia nigra (SN).1–3 It has been shown that the progress of movement disorders caused by neurodegenerative diseases is frequently accompanied by iron deposition in midbrain nuclei (i.e., red nuclei (RN) and substantia nigra).2,3 Although iron accumulation in the human brain is a normal course of aging, excessive iron deposition in midbrain nuclei was found to highly correlate with movement disorders.4 To achieve accurate diagnosis of movement disorders, previous studies used MRI to investigate the midbrain region, which is speculated to play an important role in related neurodegenerative diseases.5,6 In addition to clinical diagnosis, MRI is also used in surgical planning of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in Parkinson’s disease.7–10

Conventionally, T2- and T2*-weighted MRI can be used to image midbrain nuclei because iron deposition in the brain is paramagnetic and leads to shortened T2 and T2*. In T2*-weighted spoiled gradient-echo (SPGR) images, midbrain nuclei present hypointense signal.5 To facilitate observation of midbrain nuclei, a relatively long TE is typically chosen to achieve good contrast between midbrain nuclei and their surrounding tissues. Elolf et al. showed that a TE longer than 20 ms is required to effectively image midbrain nuclei at 3 T.5 In addition to T2- and T2*-weighted magnitude images, a previous study using T2*-weighted gradient-echo technique reported that MRI phase shift values in SN are positively correlated to unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (UPDRS) motor score.3 Furthermore, previous studies showed that susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI), a variant of T2*-weighted gradient-echo technique, can be used to enhance contrast in the midbrain.9,11–13 In SWI, filtered phase images are used to mask magnitude images, which increases sensitivity to tissue susceptibility changes such as from hemorrhage or from iron deposition.1,6–9,14–16

This study aims at imaging of midbrain nuclei with higher imaging efficiency compared to the T2*-weighted SPGR technique which is often regarded as the current clinical standard. To achieve this goal, an inverse double-echo steady-state (iDESS) sequence is proposed and compared with SPGR technique. Based on steady state free precession (SSFP) technique, iDESS acquires dual echoes within each repetition time. In this study, it is shown that iDESS not only achieves high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) but also high contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) in the midbrain. These characteristics render iDESS suitable for applications that require efficient imaging of midbrain nuclei, such as neuronal diseases related to pathological changes in midbrain including Parkinson’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy.17–19 Compared with SPGR, the shortened scan time with similar SNR and CNR brought by iDESS should help to improve the clinical image quality, which is often limited by patients’ tolerance to time-consuming MRI scans.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.A. The iDESS technique

The iDESS sequence originates from the double-echo steady-state (DESS) technique,20–27 with the main difference in the order of echo acquisition. Figure 1(a) plots the schematic sequence diagram including the readout gradient waveforms of the DESS sequence. The two echoes, fast imaging with steady-state precession (FISP) and reverse fast imaging with steady-state precession (PSIF), are acquired concurrently in a readout gradient.20,26 Figure 1(b) plots the readout gradient of the iDESS sequence, which is proposed for midbrain imaging in this study. In iDESS acquisition, two changes are made when compared to the DESS sequence: (1) the temporal acquisition order of FISP and PSIF has been reversed to enable longer phase evolutions by adjusting the pre- and rephrasing gradient areas to thrice of those in DESS and (2) separated readout gradients are used to acquire PSIF and FISP, enabling flexible adjustment of TEs for both echoes.

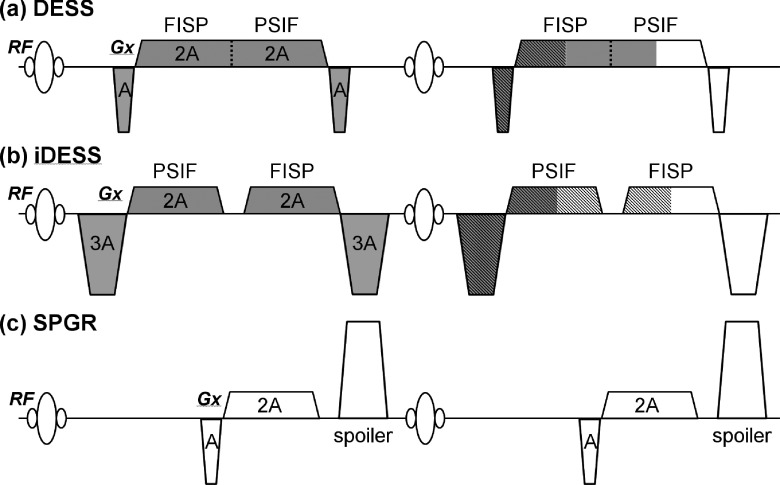

FIG. 1.

The readout gradients of the DESS (a), iDESS (b), and SPGR (c) sequences drawn for two TRs. The data are acquired within the TR shown at the right-hand side. The slashed and shaded regions indicate the gradient area cancellation to form the gradient echoes for the FISP and PSIF signals, respectively. Thus, it is seen that the FISP signal is essentially the free induction decay excited from the current RF pulse, whereas the PSIF signal is analogous to a spin-echo excited at previous TR and refocused by the RF pulse at current TR. In (b), changes in the prephasing/rephasing gradients in iDESS reverse the temporal acquisition order of FISP and PSIF. For comparison, the SPGR sequence widely used for midbrain imaging is also shown in (c). Note that a gradient spoiler, which both DESS and iDESS lack, is added after the readout window. In addition, although not shown in the figure, the two phase encoding gradients are fully balanced for DESS and iDESS sequences.

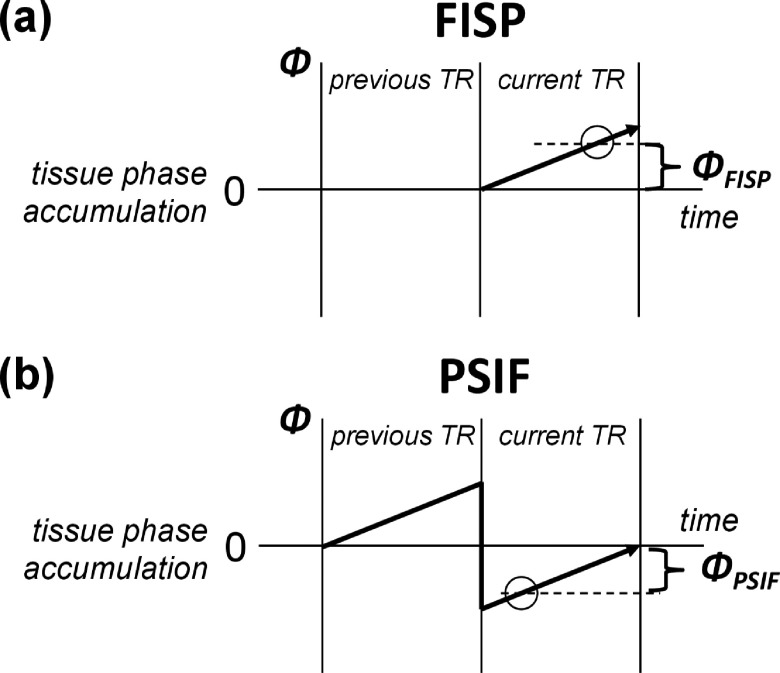

Compared with the SPGR sequence shown in Fig. 1(c), the use of DESS or iDESS for midbrain nuclei imaging is potentially advantageous due to at least two factors. First, the SPGR signal contains only the transverse magnetization excited in the current TR (i.e., free induction decay, FID). On the contrary, because no gradient spoiler is added in Figs. 1(a) and 1(b), the steady-state signal of FISP includes not only the transverse magnetization excited by the current TR (i.e., FID) but also the magnetization refocused from previous TRs. In other words, the steady-state FISP signal component with relatively long spin history from previous TRs contributes to increased signal intensities compared to SPGR. Second, since the major signal component in PSIF is the FID excited from previous TR and partially refocused at current TR, the PSIF signal experiences T2 relaxation for a temporal duration of (TRߙ+ߙTEPSIF) plus additional T2* decaying for a duration of (TRߙ−ߙTEPSIF),28 thereby presenting higher T2 contrast than SPGR at identical TR. In addition to the magnitude image characteristics mentioned above, iDESS benefits from the reversed acquisition order as compared with DESS if the tissue phase information is used to enhance contrast as in SWI processing. Figure 2(a) plots the phase accumulation of FISP, where it is seen that a long TEFISP is preferred for larger phase evolution with iron deposition and thus better depiction on the phase image. On the other hand, Fig. 2(b) shows that PSIF signal undergoes a spin-echo-like process and a short TEPSIF is preferred for generating phase contrast. In iDESS, the acquisition order of FISP after PSIF enables simultaneously longer TEFISP and shorter TEPSIF relative to DESS.

FIG. 2.

Phase accumulation of the FISP (a) and PSIF (b) signals plotted as a function of time. The data are acquired within the TR shown at the right-hand side. Since the FISP signal consists mainly of the free induction decay excited from the RF pulse, the phase evolves linearly. A long TEFISP is thus preferred to image iron deposition on the phase image. For the PSIF signal, a major component is the spin-echo excited at previous TR and refocused by the RF pulse at current TR, the phase evolution follows a decreasing trend returning to zero at the end of TR. Hence, a short TEPSIF gives a larger phase for the PSIF signal.

2.B. Composite iDESS image formation

Just like in commercial DESS imaging where the FISP and PSIF signals are summed together to form a composite image, iDESS allows composite reconstruction to optimize image contrast. In our study aiming for midbrain nuclei depiction, magnitude and phase images are calculated separately. First, iDESS magnitude images are formed by composite images of FISP and PSIF by using linear combination as shown in Eq. (1),

| (1) |

where MAGiDESS, MAGFISP, and MAGPSIF are magnitude images of iDESS, FISP, and PSIF, respectively; and w is the weighting for FISP in the composite iDESS magnitude images. By varying w from 0 to 1 (stepping 0.1), a total of 11 iDESS composite images is formed from Eq. (1), from which the optimal w is selected as that showing the highest midbrain nuclei CNR among the 11 composite images.

Reconstruction of iDESS phase images follows Eq. (2),

| (2) |

where PHAiDESS, PHAFISP, and PHAPSIF are phase images of iDESS, FISP, and PSIF, respectively. Equation (2) is meant to sum up the tissue phase accumulation both from FISP and from PSIF. The subtraction in Eq. (2) accounts for the opposite direction of FISP and PSIF phases. Through Eq. (2), the sensitivity to tissue phase accumulations in iDESS is increased, which facilitates SWI processing.

2.C. Imaging experiments

Our institutional review board approved this study. Thirteen healthy subjects (seven males, six females; 20–38 yr; 25 ± 5 yr) participated in MRI brain scans with written informed consent. Each subject underwent a total of three scans [iDESS, SPGR1 with TR, and hence scan time identical to iDESS; SPGR2 with TE and hence TR set at clinically accepted values for midbrain nuclei imaging at 3 T (Ref. 5)] covering whole brain in around 20 min. A 3 T MRI scanner (MR750, GE, Milwaukee) with an 8-channel head coil is used in this study. The common scan parameters for three scans are 3D acquisition with axial slices, matrixߙ=ߙ256 × 232 × 80, FOV ߙ=ߙ220 mm, slice thicknessߙ=ߙ2 mm, phase FOV ߙ=ߙ0.9, and bandwidthߙ=ߙ31.25 kHz. Different TR/TE/FA are set for three scans for the purpose of comparing contrast in midbrain nuclei (iDESS: TR/TEPSIF/TEFISP/FAߙ=ߙ15 ms/5 ms/10.5 ms/25°; SPGR1: TR/TE/FAߙ=ߙ15 ms/10.5 ms/9°; SPGR2: TR/TE/FAߙ=ߙ30 ms/25 ms/13°). While SPGR2 is taken as a gold standard, the SPGR1 is designed to be a control comparison with iDESS at equal scan time. Scan durations for iDESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2 are 4 min 39 s, 4 min 39 s, and 9 min 17 s, respectively. For comparison to demonstrate the phase advantage of iDESS over DESS, four of the 13 subjects underwent additional scan with DESS (TR/TEFISP/TEPSIF/FAߙ=ߙ15 ms/5 ms/10.5 ms/25°) with composite image generation similar to that described for iDESS.

All datasets are compared using original magnitude images without including phase information, as well as using phase-enhanced images following SWI processing. For the latter, standard SWI-processing procedure is applied to iDESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2, separately including the following steps.12 A high-pass-filter is applied to phase images with a kernel size of 32 cycles per field-of-view to remove background field inhomogeneity.29 The filtered phase images are then used to create a mask, which is then multiplied by the magnitude images for four times to further darken the iron-containing midbrain nuclei. Note that only the iDESS composite images with the optimal w are used for the comparison against SPGR1 and SPGR2.

2.D. SNR and CNR analyses

Signal-to-noise ratios in iDESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2 images are calculated by averaging signal from a ROI in the occipital lobe and by comparing it to noise in the background. Contrast-to-noise ratios in iDESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2 images are measured by the signal difference between red nuclei and their surrounding tissues and then divided by the background noise. Voxels showing bright intensities in iDESS images, mostly from the cerebrospinal fluid and some from the blood vessels, were carefully avoided. To compare SNR/CNR efficiency, SNRs/CNRs are normalized according to the duration of three tested protocols by dividing the measured SNR/CNR values with square root of the scan time relative to SPGR2 (i.e., SNR/CNR divided by in iDESS and SPGR1). Paired student’s t-test is used to compare iDESS with SPGR1 and SPGR2 in all subjects with statistical significance level set at p = 0.05.

3. RESULTS

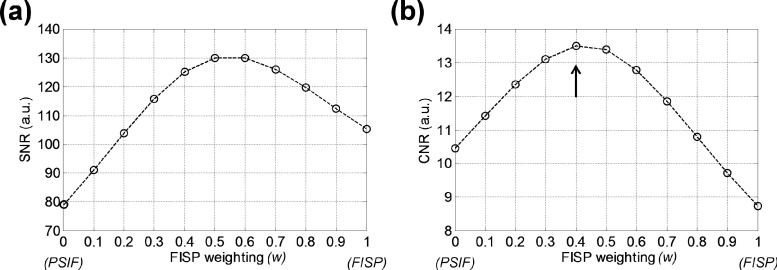

All the following results from our experiments consistently demonstrate the superiority of the iDESS technique in depicting midbrain nuclei. Figure 3 shows an example of SNR and CNR measurements as a function of the weighting factor w in the iDESS composite images from a subject (24 yr, female). One first notice that if using FISP images alone (w = 1), higher SNR [Fig. 3(a)] but lower CNR [Fig. 3(b)] is achieved than PSIF alone (w = 0) and vice versa, justifying the use of composite iDESS images. Maximum CNR of 13.49 is achieved when w = 0.4 (arrow), which is hence selected as the weighting factor for iDESS composite images. Note that the selected iDESS magnitude image at w = 0.4 also achieves a relatively high SNR of 125 among 11 composite images. Among all subjects, similar SNR and CNR curves as those in Figs. 3(a) and 3(b) are observed.

FIG. 3.

SNR in the occipital lobe (a) and CNR for the red nucleus (b) plotted as a function of the weighting factor w for the iDESS composite images of a 24 yr-old female subject. Optimal CNR of 13.49 is achieved when w = 0.4 (arrow), which also gives relatively high SNR of 125 close to the maximally achievable SNR.

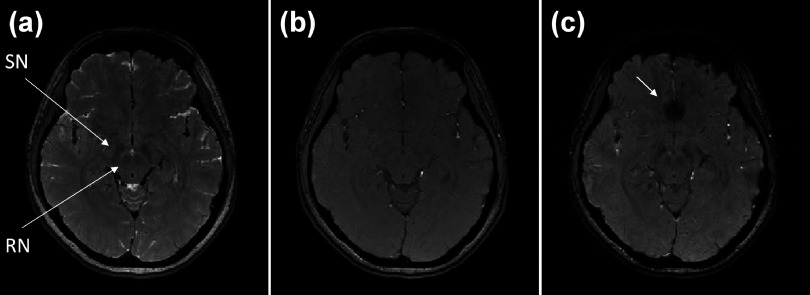

Figures 4(a), 4(b), and 4(c) compare the magnitude images of iDESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2 of the subject in Fig. 3. In Fig. 4(a), the iDESS magnitude image presents clear rendition of RN and SN while using relative short TEs (TEPSIF = 5 ms, TEFISP = 10.5 ms). For comparison with iDESS, Fig. 4(b) shows SPGR1 with TE of 10.5 ms, in which both RN and SN are barely visible even upon close inspection. With a relative long TE of 25 ms, SPGR2 in Fig. 4(c) exhibits improved image contrast in midbrain compared with SPGR1 at the expense of twice longer scan time. Notice that although midbrain image contrasts in iDESS and SPGR2 are similar, prominent susceptibility signal loss in the frontal lobe is observed in SPGR2 due to the relative long TE, as pointed out by the arrow in Fig. 4(c).

FIG. 4.

The magnitude images of iDESS (a), SPGR1 (b), and SPGR2 (c) acquired from the same subject in Fig. 3. The iDESS image shows red nuclei and substantia nigra [arrows in (a)] with a conspicuity level prominently better than SPGR1 and comparable to SPGR2. Note that although the SPGR2 image in (c) also exhibits good midbrain nuclei contrast, the scan time is twice longer than iDESS and substantial signal loss in the frontal lobe is noticeable [arrow in (c)].

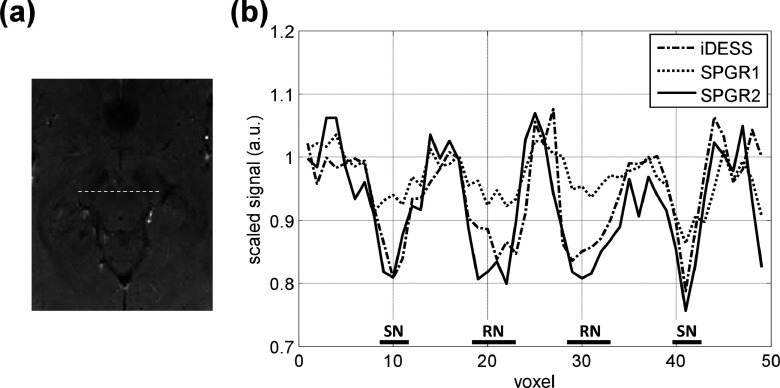

Figure 5 illustrates the signal hypointensity phenomena in midbrain nuclei in the form of spatial signal profiles plotted from images in Fig. 4. Figure 5(a) is a cropped and zoom-in image of Fig. 4(c). In Fig. 5(a), the dashed line covering both RN and SN marks the location of cross section plots in Fig. 5(b) for iDESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2. These cross section profiles, scaled and normalized by the intensity of tissues surrounding RN to allow objective comparison, show that iDESS and SPGR2 demonstrate a higher level of signal hypointensity in RN and SN when compared to SPGR1, which agrees well with visual perception from Fig. 4.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of spatial signal profiles plotted from the three images in Fig. 4. (a) Cropped image of Fig. 4(c) marks the location of cross section profile covering both RN and SN. (b) Normalized signal profiles (averaged from three adjacent lines) demonstrate superior RN and SN conspicuity for iDESS and SPGR2 compared with SPGR1.

Table I compares SNR and CNR, as well as the efficiency, of the three scans in all subjects. The average SNR values for iDESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2 are 121.2 ± 11.3, 112.2 ± 8.4, and 95.5 ± 16.4, separately. Among the three scans, iDESS (171.3) presents the highest SNR efficiency with statistical significance compared to SPGR1 (158.7, p = 0.013) and SPGR2 (95.5, p < 10−8). The measured CNRs in red nuclei for iDESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2 are 13.6 ± 3.3, 4.9 ± 1.7, and 14.3 ± 5.9, respectively. Similar to comparison in SNR efficiency, iDESS (19.2) achieves higher CNR efficiency than both SPGR1 (6.9, p < 10−6) and SPGR2 (14.3, p = 0.0016).

TABLE I.

Comparison of SNR/CNR efficiencies among iDESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2.

| iDESS | SPGR1 | SPGR2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scan time | 4 min 39 s | 4 min 39 s | 9 min 17 s |

| SNR | 121.2 ± 11.3 | 112.2 ± 8.4 | 95.5 ± 16.4 |

| SNR efficiencya (p-value) | 171.3 | 158.7 (p = 0.013)b | 95.5 (p < 10−8)b |

| CNR | 13.6 ± 3.3 | 4.9 ± 1.7 | 14.3 ± 5.9 |

| CNR efficiencya (p-value) | 19.2 | 6.9 (p < 10−6)b | 14.3 (p = 0.0016)b |

SNR/CNR efficiencies are calculated using SNR/CNR values divided by square root of the scan time compared to SPGR2 (i.e., SNR/CNR divided by in iDESS and SPGR1).

Statistically significant (p < 0.05).

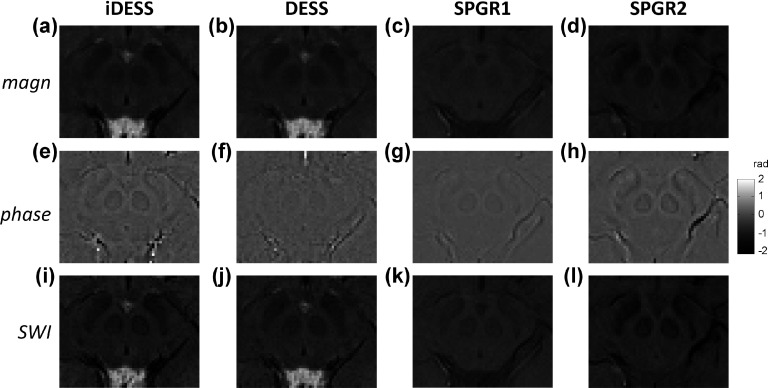

Figures 6(a)–6(d) show midbrain images of iDESS, DESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2 from another subject (23 yr, female), demonstrating the comparative effects of SWI processing. Without SWI processing, iDESS, DESS, and SPGR2 magnitude images exhibit higher contrast in the midbrain, as opposed to the barely visible midbrain nuclei in SPGR1. Figures 6(e)–6(h) are the filtered phase images of iDESS, DESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2. It has to be noted that even though the iDESS dataset is acquired with relatively short TEs of 5 and 10.5 ms, the iDESS phase image in (e) achieves high contrast in the midbrain, at a level similar to that of SPGR2 acquired using a TE of 25 ms as shown in (h). In contrast, both DESS and SPGR1 phase images show relatively low contrast in midbrain, reflecting inadequate susceptibility-induced phase evolution due to low TE (e.g., 10.5 ms for SPGR1). With SWI processing, the images from iDESS, DESS, SPGR1, and SPGR2 computationally enhanced by masking magnitude images [(a)–(d)] with phase images [(e)–(h)] are shown in Figs. 6(i)–6(l), respectively. It can be seen that SWI processing further improves midbrain contrast in iDESS [Fig. 6(i)] and SPGR2 [Fig. 6(l)] compared to their corresponding magnitude images in (a) and (d), particularly at the boundaries of RN and SN. In DESS and SPGR1 SWI of Figs. 6(j) and 6(k), although image contrast is improved by phase masking compared to its magnitude image in Figs. 6(b) and 6(c), they still present relatively lower visibility of midbrain nuclei compared with the other two methods investigated in this study.

FIG. 6.

Magnitude (top row), phase (middle row), and SWI-processed images (bottom row) of iDESS (first column from left), DESS (second column), SPGR1 (third column), and SPGR2 (fourth column) data from a 23 yr-old female subject. For midbrain nuclei depiction, iDESS and SPGR2 not only demonstrate superior contrast compared with SPGR1 on the original magnitude images [(a)–(d)] but also show greater phase evolution evidenced from the phase images [(e)–(h)]. iDESS shows largely similar behavior to DESS on magnitude images [(a) vs (b)], with enhanced midbrain conspicuity on the phase image [(e) vs (f)] and the corresponding SWI-processed images [(i) vs (j)]. Note that iDESS uses relatively shorter TEs of 5 and 10.5 ms to achieve phase values in the midbrain nuclei (e) similar to that in SPGR2 at a TE of 25 ms (h). Comparisons of SWI-processed images [(i)–(l)] give consistent results as in the original magnitude images.

4. DISCUSSION

For imaging of midbrain nuclei, the T2*-weighted spoiled gradient-echo technique has gained popularity because of its high sensitivity to iron deposition in midbrain nuclei.5–7 However, in SPGR, clear depiction of midbrain necessitates a relatively long TE and, thus, results in long scan time. In this study, we propose the iDESS sequence which contains three innovative parts. First, the modification of gradient scheme in iDESS involves redesigning SSFP echo pathways so that two echoes can be generated in a reversed order compared to DESS.30 Second, the separate control of two echoes in iDESS allows optimization of both FISP and PSIF for midbrain imaging. Third, the increased tissue phase sensitivity in iDESS compared with DESS enables SWI processing. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to apply the iDESS concept to MR imaging of the midbrain nuclei. As a result, the iDESS technique, where its PSIF signal experiences T2 relaxation period longer than TR, allows shortened scan time without sacrificing red nuclei contrast. In addition, iDESS achieves high signal intensities by using steady-state magnetization excited in previous TRs, plus the integration of the FISP signal to further increase SNR. Altogether, these properties result in the high SNR efficiency of iDESS, while keeping good iron deposition contrast at reduced scan time. The SNR advantage of iDESS facilitates its incorporation with accelerated imaging methods, such as partial Fourier imaging or parallel imaging, for applications that requires high SNR to exchange for fast image acquisition.

The formation of composite iDESS magnitude images by weighted combination of the FISP and PSIF echoes achieves simultaneously high SNR and CNR compared to using the FISP or PSIF images alone, as experimentally shown in Fig. 3. It is anticipated that the SNR gain is attributed more to the FISP echo which bears the FID nature experiencing relatively less T2 relaxation, whereas the improved CNR for iron deposition is likely due to the contribution from the spin-echo-like PSIF signal. In this study, where the specific aim is midbrain nuclei imaging, the image with the highest red nuclei CNR at w = 0.4 is selected among all composite images. Nonetheless, the weighting factor used in this study does not preclude future extensions of the iDESS composite magnitude image for other applications, such as the optimization of SNR (Ref. 24) or diffusion contrast31 by flexibly adjusting the weighting factor or by using other means to combine the FISP and PSIF data.

Subtle difference in T2 and T2* contrasts exists between the nonsteady-state SPGR signal and the steady-state PSIF signal in DESS or iDESS. The SPGR signal simply experiences T2* decaying for a time period of TE. The PSIF signal, on the other hand, exhibits T2 relaxation for a time period of (TRߙ+ߙTEPSIF) plus T2* decaying for a time period of (TRߙ−ߙTEPSIF).28 Fortunately, in the midbrain nuclei, T2 and T2* shortenings both exist: iron deposition leads to inhomogeneous magnetic field distribution within the nuclei and hence a shortened T2*, whereas random molecular diffusion in the presence of field inhomogeneity also causes reduced T2.32 As a result, the combined effects from T2 and T2* decreases not only give iDESS images the desired midbrain nuclei conspicuity similar to the T2* contrast shown in SPGR2 but also bring up the important advantage of better immunity to susceptibility-related signal loss from air-tissue interfaces. Specifically, the T2* decaying intervals are (15 − 5)ߙ=ߙ10 ms for iDESS and 25 ms for SPGR2, respectively. The improved signals near the frontal lobe for iDESS compared with SPGR2 at nearly identical iron deposition contrast are clearly evidenced from Fig. 4.

Compared with DESS, the iDESS technique provides phase advantages for computational enhancement of the paramagnetic susceptibility contrast using SWI processing; in that switching, the order of the FISP and PSIF echoes helps expanding the phase evolution for both signals. Phase image subtraction of the two FISP and PSIF echoes with opposite phase further increases the sensitivity to tissue phase accumulation by a factor of two, compared to single-echo acquisition at identical TE such as SPGR1 used in this study. Last but not the least, the increased phase sensitivity of iDESS may find unique clinical applications where tissue characterization using quantitative phase information is helpful.33,34

One potential concern for acquisition methods used in this study is subject motion. For this aspect, we anticipate that the influence from interecho motion in iDESS should be minimal, as any involuntary motion within echo spacing of 5.5 ms is likely negligible. In contrast, with the reduction of total scan time from 9 min for SPGR2 to less than 5 min for iDESS, the apparent benefits regarding motion influences would very likely far exceed the potential pitfall of interecho motion due to two-echo acquisition. However, the tolerance of iDESS to subject motion needs to be systematically and quantitatively evaluated in future studies.

A limitation of the current iDESS implementation is the lack of flow compensation, which would affect the signal intensities in regions such as the ventricles or blood vessels. Therefore, the current iDESS implementation is not suitable for visualizing veins using SWI processing.11,12 Quantitative analysis involving phase values should also be carefully exercised before putting into clinical practice. For the two phase encoding directions, flow compensation can be added as, in general, gradient-echo sequences.35 Flow compensation along the readout direction, however, may be somewhat complicated for iDESS because the current waveforms for the readout gradients are specifically designed for controlling echo formation. The absence of flow compensation may partially account for the inconsistent signal intensities of the cerebrospinal fluid, as seen in Fig. 4(a). A second limitation is that quantitative T2* mapping, which shows potential for iron content quantification,36–38 has not been integrated into the iDESS sequence. Nevertheless, we regard this restriction as largely temporary, which by no means preclude further developments to expand our currently qualitative technique to a larger-scale quantitative investigation. Future employment of multiecho acquisition in steady-state sequences39 is among the many possibilities that may help achieve this goal.

We conclude that the iDESS technique for midbrain nuclei imaging is an efficient method that could achieve similar CNR at increased SNR in reduced scan time compared to the SPGR method that is widely used clinically. In addition, iDESS is less prone to susceptibility signal loss from air-tissue interfaces because of relatively shorter T2* decaying duration. The high potential of iDESS therefore warrants further detailed investigations to explore its imaging characteristics in neurological applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mind Research and Imaging Center (MRIC), National Cheng Kung University for research support. The authors were supported in part under grant numbers NSC-101-2221-E-006-063-MY2 (MLW), NSC-100-2218-E-006-038-MY2 (TCC), MOST-102-2221-E-006-017- (TCC), NIH R01-NS074045 (HCC and NKC) and NIH R21-EB018419 (NKC).

This study was presented in part at the 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2012, Melbourne, Australia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hingwala D. R., Kesavadas C., Thomas B., and Kapilamoorthy T. R., “Susceptibility weighted imaging in the evaluation of movement disorders,” Clin. Radiol. 68, e338–e348 (2013). 10.1016/j.crad.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michaeli S., Oz G., Sorce D. J., Garwood M., Ugurbil K., Majestic S., and Tuite P., “Assessment of brain iron and neuronal integrity in patients with Parkinson’s disease using novel MRI contrasts,” Mov. Disord. 22, 334–340 (2007). 10.1002/mds.21227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J., Zhang Y., Wang J., Cai P., Luo C., Qian Z., Dai Y., and Feng H., “Characterizing iron deposition in Parkinson’s disease using susceptibility-weighted imaging: An in vivo MR study,” Brain Res. 1330, 124–130 (2010). 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dexter D. T., Wells F. R., Lees A. J., Agid F., Agid Y., Jenner P., and Marsden C. D., “Increased nigral iron content and alterations in other metal ions occurring in brain in Parkinson’s disease,” J. Neurochem. 52, 1830–1836 (1989). 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07264.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elolf E., Bockermann V., Gringel T., Knauth M., Dechent P., and Helms G., “Improved visibility of the subthalamic nucleus on high-resolution stereotactic MR imaging by added susceptibility (T2*) contrast using multiple gradient echoes,” Am. J. Neuroradiol. 28, 1093–1094 (2007). 10.3174/ajnr.A0527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerl H. U., Gerigk L., Huck S., Al-Zghloul M., Groden C., and Nolte I. S., “Visualisation of the zona incerta for deep brain stimulation at 3.0 Tesla,” Clin. Neuroradiol. 22, 55–68 (2012). 10.1007/s00062-012-0136-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerl H. U., Gerigk L., Pechlivanis I., Al-Zghloul M., Groden C., and Nolte I., “The subthalamic nucleus at 3.0 Tesla: Choice of optimal sequence and orientation for deep brain stimulation using a standard installation protocol: Clinical article,” J. Neurosurg. 117, 1155–1165 (2012). 10.3171/2012.8.JNS111930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lefranc M., Derrey S., Merle P., Tir M., Constans J. M., Montpellier D., Macron J. M., Le Gars D., Peltier J., Baledentt O., and Krystkowiak P., “High-resolution 3-dimensional T2*-weighted angiography (HR 3-D SWAN): An optimized 3-T magnetic resonance imaging sequence for targeting the subthalamic nucleus,” Neurosurgery 74, 615–627 (2014). 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young G. S., Feng F., Shen H., and Chen N. K., “Susceptibility-enhanced 3-Tesla T1-weighted spoiled gradient echo of the midbrain nuclei for guidance of deep brain stimulation implantation,” Neurosurgery 65, 809–815 (2009). 10.1227/01.NEU.0000345354.21320.D1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao Y., Beriault S., Pike G. B., and Collins D. L., “Multicontrast multiecho FLASH MRI for targeting the subthalamic nucleus,” Magn. Reson. Imaging 30, 627–640 (2012). 10.1016/j.mri.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haacke E. M., Mittal S., Wu Z., Neelavalli J., and Cheng Y. C., “Susceptibility-weighted imaging: Technical aspects and clinical applications, part 1,” Am. J. Neuroradiol. 30, 19–30 (2009). 10.3174/ajnr.A1400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haacke E. M., Xu Y., Cheng Y. C., and Reichenbach J. R., “Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI),” Magn. Reson. Med. 52, 612–618 (2004). 10.1002/mrm.20198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mittal S., Wu Z., Neelavalli J., and Haacke E. M., “Susceptibility-weighted imaging: Technical aspects and clinical applications, part 2,” Am. J. Neuroradiol. 30, 232–252 (2009). 10.3174/ajnr.A1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo J., Jagadeesan B. D., Cross A. H., and Yablonskiy D. A., “Gradient echo plural contrast imaging–Signal model and derived contrasts: T2*, T1, phase, SWI, T1f, FST2*, and T2*-SWI,” NeuroImage 60, 1073–1082 (2012). 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Gorman R. L., Shmueli K., Ashkan K., Samuel M., Lythgoe D. J., Shahidiani A., Wastling S. J., Footman M., Selway R. P., and Jarosz J., “Optimal MRI methods for direct stereotactic targeting of the subthalamic nucleus and globus pallidus,” Eur. Radiol. 21, 130–136 (2011). 10.1007/s00330-010-1885-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vertinsky A. T., Coenen V. A., Lang D. J., Kolind S., Honey C. R., Li D., and Rauscher A., “Localization of the subthalamic nucleus: Optimization with susceptibility-weighted phase MR imaging,” Am. J. Neuroradiol. 30, 1717–1724 (2009). 10.3174/ajnr.A1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta D., Saini J., Kesavadas C., Sarma P. S., and Kishore A., “Utility of susceptibility-weighted MRI in differentiating Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism,” Neuroradiology 52, 1087–1094 (2010). 10.1007/s00234-010-0677-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han Y. H., Lee J. H., Kang B. M., Mun C. W., Baik S. K., Shin Y. I., and Park K. H., “Topographical differences of brain iron deposition between progressive supranuclear palsy and parkinsonian variant multiple system atrophy,” J. Neurol. Sci. 325, 29–35 (2013). 10.1016/j.jns.2012.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiter E., Mueller C., Pinter B., Krismer F., Scherfler C., Esterhammer R., Kremser C., Schocke M., Wenning G. K., Poewe W., and Seppi K., “Dorsolateral nigral hyperintensity on 3.0 T susceptibility-weighted imaging in neurodegenerative parkinsonism,” Mov. Disord. (2015) [E-pub ahead of print]. 10.1002/mds.26171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruder H., Fischer H., Graumann R., and Deimling M., “A new steady-state imaging sequence for simultaneous acquisition of two MR images with clearly different contrasts,” Magn. Reson. Med. 7, 35–42 (1988). 10.1002/mrm.1910070105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eckstein F., Hudelmaier M., Wirth W., Kiefer B., Jackson R., Yu J., Eaton C. B., and Schneider E., “Double echo steady state magnetic resonance imaging of knee articular cartilage at 3 Tesla: A pilot study for the osteoarthritis initiative,” Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65, 433–441 (2006). 10.1136/ard.2005.039370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedrich K. M., Reiter G., Kaiser B., Mayerhofer M., Deimling M., Jellus V., Horger W., Trattnig S., Schweitzer M., and Salomonowitz E., “High-resolution cartilage imaging of the knee at 3T: Basic evaluation of modern isotropic 3D MR-sequences,” Eur. J. Radiol. 78, 398–405 (2011). 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavdas E., Topalzikis T., Mavroidis P., Kyriakis I., Roka V., Kostopoulos S., Glotsos D., Zilidis C., Stathakis S., Tsagkalis A., Papanikolaou N., Batsikas G., Arvanitis D. L., and Vassiou K., “Comparison of PD BLADE with fat saturation (FS), PD FS, and T2 3D DESS with water excitation (WE) in detecting articular knee cartilage defects,” Magn. Reson. Imaging 31, 1255–1262 (2013). 10.1016/j.mri.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moriya S., Miki Y., Kanagaki M., Matsuno Y., and Miyati T., “90 degrees -flip-angle three-dimensional double-echo steady-state (3D-DESS) magnetic resonance imaging of the knee: Isovoxel cartilage imaging at 3T,” Eur. J. Radiol. 83, 1429–1432 (2014). 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterfy C. G., Schneider E., and Nevitt M., “The osteoarthritis initiative: Report on the design rationale for the magnetic resonance imaging protocol for the knee,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage 16, 1433–1441 (2008). 10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welsch G. H., Scheffler K., Mamisch T. C., Hughes T., Millington S., Deimling M., and Trattnig S., “Rapid estimation of cartilage T2 based on double echo at steady state (DESS) with 3 Tesla,” Magn. Reson. Med. 62, 544–549 (2009). 10.1002/mrm.22036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wirth W., Nevitt M., Hellio Le Graverand M. P., Benichou O., Dreher D., Davies R. Y., Lee J., Picha K., Gimona A., Maschek S., Hudelmaier M., Eckstein F., and Investigators O. A. I., “Sensitivity to change of cartilage morphometry using coronal FLASH, sagittal DESS, and coronal MPR DESS protocols–Comparative data from the osteoarthritis initiative (OAI),” Osteoarthritis Cartilage 18, 547–554 (2010). 10.1016/j.joca.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheffler K., “Fast frequency mapping with balanced SSFP: Theory and application to proton-resonance frequency shift thermometry,” Magn. Reson. Med. 51, 1205–1211 (2004). 10.1002/mrm.20081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang H. C., Chuang T. C., Chung H. W., Lin H. S., Lai P. H., Weng M. J., Fu J. H., Wang P. C., Li S. C., and Pan H. B., “Multilayer appearance on contrast-enhanced susceptibility-weighted images on patients with brain abscesses: Possible origins and effects of postprocessing,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 36, 1353–1361 (2012). 10.1002/jmri.23766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheffler K., “A pictorial description of steady-states in rapid magnetic resonance imaging,” Concepts Magn. Reson. 11, 291–304 (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staroswiecki E., Granlund K. L., Alley M. T., Gold G. E., and Hargreaves B. A., “Simultaneous estimation of T(2) and apparent diffusion coefficient in human articular cartilage in vivo with a modified three-dimensional double echo steady state (DESS) sequence at 3 T,” Magn. Reson. Med. 67, 1086–1096 (2012). 10.1002/mrm.23090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meiboom S. and Gill D., “Modified spin-echo method for measuring nuclear relaxation times,” Rev. Sci. Instrum. 29, 688–691 (1958). 10.1063/1.1716296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai P. H., Chang H. C., Chuang T. C., Chung H. W., Li J. Y., Weng M. J., Fu J. H., Wang P. C., Li S. C., and Pan H. B., “Susceptibility-weighted imaging in patients with pyogenic brain abscesses at 1.5T: Characteristics of the abscess capsule,” Am. J. Neuroradiol. 33, 910–914 (2012). 10.3174/ajnr.A2866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaitsu Y., Kudo K., Terae S., Yazu R., Ishizaka K., Fujima N., Tha K. K., Haacke E. M., Sasaki M., and Shirato H., “Mapping of cerebral oxygen extraction fraction changes with susceptibility-weighted phase imaging,” Radiology 261, 930–936 (2011). 10.1148/radiol.11102416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao G., Parker D. L., Sherrill D. S., and Du Y. P., “Abbreviated moment-compensated phase encoding,” Magn. Reson. Med. 34, 179–185 (1995). 10.1002/mrm.1910340208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langkammer C., Krebs N., Goessler W., Scheurer E., Ebner F., Yen K., Fazekas F., and Ropele S., “Quantitative MR imaging of brain iron: A postmortem validation study,” Radiology 257, 455–462 (2010). 10.1148/radiol.10100495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peran P., Cherubini A., Luccichenti G., Hagberg G., Demonet J. F., Rascol O., Celsis P., Caltagirone C., Spalletta G., and Sabatini U., “Volume and iron content in basal ganglia and thalamus,” Hum. Brain Mapp. 30, 2667–2675 (2009). 10.1002/hbm.20698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanchez-Castaneda C., Squitieri F., Di Paola M., Dayan M., Petrollini M., and Sabatini U., “The role of iron in gray matter degeneration in Huntington’s disease: A magnetic resonance imaging study,” Hum. Brain Mapp. 36, 50–66 (2015). 10.1002/hbm.22612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng C., Chung H., Chao T., and Madore B., Presented at the Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine ISMRM 21th Annual Meeting, Salt Lake City, UT (2013). [Google Scholar]