Abstract

Background

Ependymomas are rare CNS tumors. Previous studies describing the clinical course of ependymoma patients were restricted to small sample sizes, often with patients at a specific institution.

Methods

Clinically annotated ependymoma tissue samples from 19 institutions were centrally reviewed. Patients were all adults aged 18 years or older at the time of diagnosis. Potential prognostic clinical factors identified on univariate analysis were included in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model with backwards selection to model progression-free survival.

Results

The 282 adult ependymoma patients were equally male and female with a mean age of 43 years (range, 18–80y) at diagnosis. The majority were grade II (78%) with the tumor grade for 20 cases being reclassified on central review (half to higher grade). Tumor locations were spine (46%), infratentorial (35%), and supratentorial (19%). Tumor recurrence occurred in 26% (n = 74) of patients with a median time to progression of 14 years. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model identified supratentorial location (P < .01), grade III (anaplastic; P < .01), and subtotal resection, followed or not by radiation (P < .01), as significantly increasing risk of early progression.

Conclusions

We report findings from an ongoing, multicenter collaboration from a collection of clinically annotated adult ependymoma tumor samples demonstrating distinct predictors of progression-free survival. This unique resource provides the opportunity to better define the clinical course of ependymoma for clinical and translational studies.

Keywords: adult, ependymoma, progression-free survival

Ependymoma is a rare tumor that accounts for 2%–3% of all primary central nervous system tumors.1,2 The World Health Organization (WHO) grade classification system provides 3 grades of ependymoma with the most malignant being grade III and entitled anaplastic ependymoma.3,4 Ependymomas occur in both the pediatric and adult populations and occur in both the brain and spine. They can also appear, rarely, outside the central nervous system.5,6 Due to its rarity, research has mainly included only small numbers of samples from specific institutions with limited treatment and disease course information.7,8 Researchers exploring the established databases, such as the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) and the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS), have reported on the incidence and survival of ependymoma patients,9–13 but these reports are limited by data quality, particularly accuracy of pathological diagnosis and extent of information regarding treatment. Review of the reported literature to date has shown the extent of surgery, tumor location, and tumor grade to be important to progression-free survival (PFS) in adult patients based on these small studies.2,14,15

To address the limitations of previous studies, the Collaborative Ependymoma Research Network (CERN Foundation)16 developed a multi-institutional, clinically annotated tissue repository in September 2009. It was developed to study the clinical course of patients with ependymoma from multiple institutions around the world, to identify clinically relevant molecular markers that define molecular subtypes of ependymoma, and to correlate these clinical and molecular factors with patient outcome. The purpose of this report is to further define the clinical and demographic factors associated with PFS in adult patients with ependymoma involving the brain and spine.

Methods

The CERN Ependymoma Correlative Tissue Repository was approved by Institutional Review Boards or their equivalents at each of the participating centers. Any patient with an ependymoma in the brain or spine may be registered to the study. All registered participants must have a paraffin tissue block with at least 1 cm2 of tumor available for central review. All samples underwent central review (by KA) to confirm diagnosis and tumor grade. Once the diagnosis of ependymoma was confirmed, the clinical history of the participant was collected including: (i) tumor characteristics: location, grade; (ii) diagnosis details: extent of initial resection (as described in operative reports and postoperative imaging), previous misdiagnoses, other cancers; (iii) treatment history: number of surgeries, radiation and chemotherapy treatments and their types; and (iv) outcome information: progression/recurrence status and details and current vital status. In order to have sufficient outcome data, participants with spinal ependymoma were required to have had at least 4 years of follow-up from diagnosis available to be eligible, unless the patient had a progression, recurrence, or death before 4 years.7,11 Participants aged 18 years and older at diagnosis were classified as adults, as has been the standard in other reports.

Statistical Methods

All statistical analyses were performed on IBM SPSS Statistics Version 19.17 Descriptive statistics were used for the frequency of participant characteristics. Chi-square tests revealed associations between variables. In order to interpret the effect of age in a more clinically relevant manner, age at diagnosis was dichotomized into 2 groups: younger and older than the median age. PFS was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the first tumor recurrence or the last follow-up date or date of death in the absence of documented progression. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate the PFS. Log-rank tests were used to determine significant differences in survival distributions among groups. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was fitted to identify the best prognostic factors of shorter progression-free times. Variables with P < .05 were considered significantly relevant. Hazard ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Any variable that was identified as a potential prognostic factor in univariate analysis was included in the multivariate step. The variables of interest were age at diagnosis (dichotomized younger or older than sample median age), tumor grade by WHO classification3 (I, II, III), tumor location (supratentorial, infratentorial, or spine), and initial treatment regimen as determined by the individual collaborating sites and according to study definitions (gross total resection followed by observation [GTR], subtotal resection followed by observation [STR], gross total resection followed by radiation [GTR + radiation], and biopsy/subtotal resection followed by radiation [STR + radiation]).

Results

At the time of this analysis, 19 medical institutions were participating in the study (16 in the United States, 2 in Europe, and 1 in Canada). Tumor tissue from 674 patients (including 360 adult patients) had undergone central review to confirm eligibility. Two hundred eighty-two adult patients had clinically annotated tumor samples available for the present analysis. Seventy-eight patients were found to be ineligible, with the primary reason being insufficient tumor tissue remaining in the block for inclusion in the central repository. Ten patients were found to have a different nonependymoma glial tumor after the central review (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1).

Sample Characteristics

The 282 participants were equally male and female (51% vs 49%) with most being white non-Hispanic (86%). The median age at diagnosis was 43 years (mean, 44y; range, 18–80y). All 3 levels of the WHO grade classification were represented, with grade II being the most common (78%). All grade I tumors were myxopapillary ependymomas. During the central review, the tumor grade was reclassified for 20 participants (7%) with 11 moving to a higher grade. The reclassified tumor grade was used in the analysis for these 20 participants. As expected, the spine was the most common tumor location (46%), with most in the cervical spine (33%). Twenty-one participants (7%) had originally received a misdiagnosis, with their tumor more frequently being called an astrocytoma (n = 9) (see Supplementary material, Table S1). Participants were diagnosed with ependymoma between 1972 and 2011, with available follow-up from diagnosis ranging from zero to 27 years. Table 1 further describes the participant sample.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics and clinical details by tumor location

| All (n = 282) | Supratentorial Brain n = 53 (19%) | Infratentorial Brain n = 100 (35%) | Spine n = 129 (46%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 44 (15) | 38 (13) | 47 (14) | 44 (15) |

| Range | 18–80 | 18–65 | 21–75 | 18–80 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 143 (51) | 28 (53) | 53 (53) | 62 (48) |

| Female | 139 (49) | 25 (47) | 47 (47) | 67 (52) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White non-Hispanic | 242 (86) | 49 (93) | 85 (85) | 108 (84) |

| Hispanic | 15 (5) | 2 (4) | 3 (3) | 10 (8) |

| Black | 12 (4) | 2 (4) | 7 (7) | 3 (2) |

| Asian | 4 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Unknown | 9 (3) | 0 | 4 (4) | 5 (4) |

| Tumor grade, n (%) | ||||

| I | 30 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 | 30 (23) |

| II | 221 (78) | 32 (60) | 93 (93) | 96 (74) |

| III | 31 (11) | 21 (40) | 7 (7) | 3 (2) |

| Initial treatmenta, n (%) | ||||

| GTR | 161 (57) | 15 (28) | 51 (51) | 95 (74) |

| STR | 35 (12) | 6 (11) | 16 (16) | 13 (10) |

| STR + radiation | 55 (20) | 14 (26) | 23 (23) | 18 (14) |

| GTR + radiation | 31 (11) | 18 (34) | 10 (10) | 3 (2) |

| Initial radiation method, n (%) | ||||

| Conventional | 66 (77) | 26 (81) | 23 (70) | 17 (81) |

| IMRT | 13 (15) | 5 (16) | 7 (21) | 1 (5) |

| Radiosurgery | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Missing | 6 (7) | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | 3 (14) |

| Initial Chemotherapyb, n (%) | 10 (4) n (%) | 7 (13) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Initial chemotherapy agents | ||||

| Alkylating | 7 (70) | 6 (86) | 0 | 1 (50) |

| ICE variation | 2 (20) | 1 (14) | 0 | 1 (50) |

| Missing | 1 (10) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 |

| Initial chemotherapy cycles | ||||

| Median | 6 | 4 | – | 9 |

| Range | 3–12 | 3–6 | – | 6–12 |

| Median survival | Not reached | 7.8 | Not reached | Not reached |

| 5-year survival Rate | 87% | 62% | 85% | 97% |

| 5-year PFS Rate | 77% | 38% | 78% | 87% |

Abbreviations: GTR, gross total resection followed by observation; GTR + radiation, gross total resection followed by radiation; STR, subtotal resection followed by observation; STR + radiation, subtotal resection followed by radiation.

aInitial Treatment Variable is categorized as gross total resection followed by observation, subtotal resection followed by observation, subtotal resection followed by radiation, and gross total resection followed by radiation.

bChemotherapy either with or following radiation.

In terms of treatment, most participants underwent a GTR followed by observation (57%). Radiation was given after both subtotal resections (STR + radiation = 20%) and gross total resections (GTR + radiation = 11%). For those who did receive radiation, it was most frequently conventional (external beam) radiation (77%) to the involved field (77%), and only 8% received craniospinal radiation treatment. Only 10 participants received chemotherapy along with or closely following their radiation treatment, and this was most commonly an alkylating chemotherapy agent (70%). Table 1 details the clinical characteristics.

Progression-free Survival

Twenty-six percent of participants had at least 1 recurrence or progression, while 6% had at least 3 recurrences or progressions. The majority of the recurrences occurred in the same location as the original tumor (65%). A variety of treatments were used at the time of the first recurrence, with tumor resection being the most common (64%). Radiation treatment was then administered after surgery in 22% of participants, and 7% had subsequent chemotherapy. Table 2 details the recurrence or progression specifics.

Table 2.

Recurrence/progression specifics by tumor location

| All (n = 282) | Supratentorial Brain n = 53 (19) | Infratentorial Brain n = 100 (35) | Spine n = 129 (46) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of progressions, n (%) | ||||

| None | 208 (74) | 26 (49) | 74 (74) | 108 (84) |

| 1 | 46 (16) | 11 (21) | 19 (19) | 16 (12) |

| 2 | 10 (4) | 5 (9) | 5 (5) | 0 |

| ≥3 | 18 (6) | 11 (21) | 2 (2) | 5 (4) |

| Location, n (%) | ||||

| Same as original | 48 (65) | 19 (70) | 15 (58) | 14 (67) |

| Different from original | 12 (16) | 3 (11) | 6 (23) | 3 (14) |

| Original plus additional | 8 (11) | 3 (11) | 3 (12) | 2 (10) |

| Unknown site | 6 (8) | 2 (7) | 2 (8) | 2 (10) |

| Treatment at first recurrence, n (%) | ||||

| None | 6 (8) | 1 (4) | 5 (19) | |

| Surgery only | 26 (35) | 7 (26) | 8 (31) | 11 (52) |

| Radiation only | 12 (16) | 5 (19) | 4 (15) | 3 (14) |

| Chemotherapy only | 6 (8) | 3 (11) | 1 (4) | 2 (10) |

| Surgery and radiation | 16 (22) | 7 (26) | 8 (31) | 1 (5) |

| Surgery and chemotherapy | 5 (7) | 3 (11) | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Other combinations | 3 (4) | 1 (4) | 0 | 2 (10) |

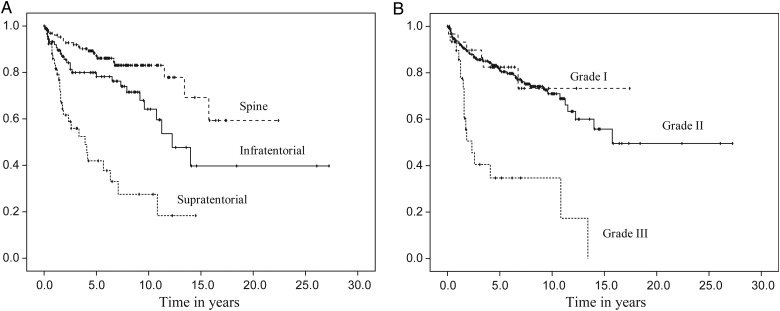

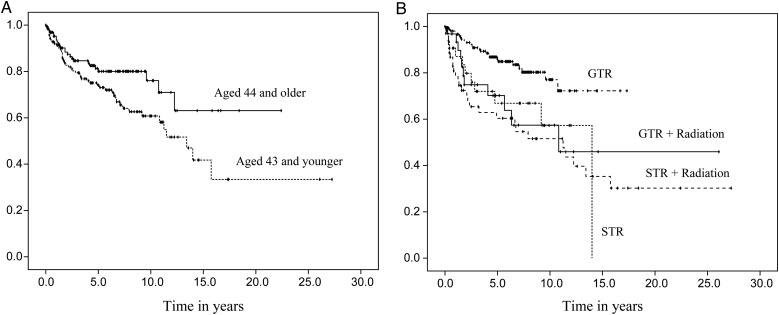

Median time to recurrence was 14 years for the sample as a whole (range, 0.1–27.3y; 95% CI, 10.1–17.9). A log-rank test revealed a significant difference in the PFS among the 3 tumor locations (χ2 = 46.4, P < .01). Kaplan-Meier curves estimated the median time to progression at 3.9 years for the supratentorial brain region (95% CI, 2.1–5.7) and 12.3 years for the infratentorial brain region (95% CI, 9.1–15.4). A median time was not reached for participants with a spine location; however, 59% did not have a progression at 15.8 years. When reported by tumor grade, grade III had the shortest progression-free time, with a median of 2.3 years (95% CI, 1.2–3.5) (χ2 = 33.7, P < .01). There was also a significant difference in PFS according to initial treatment (χ2 = 19.9, P < .01). Participants who underwent a subtotal resection, followed or not by radiation, had a shorter progression-free time compared with those who underwent a gross total resection, followed or not by radiation. Finally, participants aged 43 years or younger at diagnosis had a shorter progression-free time (median = 13.4y; 95% CI, 10.6–16.2) than those aged 44 years and older (median not reached). Figs. 1 and 2 display the PFS distributions by variables of interest.

Fig. 1.

Progression-free survival distributions by tumor characteristics. Caption: Progression-free survival distributions according to tumor location (A) and tumor grade (B).

Fig. 2.

Progression-free survival distributions by age at diagnosis (A) and initial treatment (B).

Prognostic Factors for Shorter Progression-free Survival

A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model for PFS was fitted using the following variables (based on univariate analysis): tumor location, tumor grade, age, and initial treatment. A backward stepwise selection revealed that tumor location, tumor grade, and initial treatment all contributed significantly to PFS. As seen in Table 3, participants with infratentorial tumors or spine tumors were less likely to progress than those with supratentorial tumors (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.33; 95% CI, 0.18–0.63; P < .01 and HR = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.07–0.31; P < 0.01, respectively). Tumor grade was also associated with outcome; the diagnosis of a grade III tumor raised a participant's risk of progression when compared with a grade II tumor (HR = 3.00; 95% CI, 1.45–6.07; P < .01). There was no difference in PFS between grade I and grade II tumors (P = .19). Lastly, having undergone only a biopsy or subtotal resection either alone or followed by radiation increased the hazard of tumor progression or recurrence when compared with GTR (HR = 2.61; 95% CI, 1.27–5.36; P < .01 and HR = 2.44; 95% CI, 1.36–4.36; P < .01, respectively). Participants with GTR alone did as well as those with GTR + radiation (P < .27).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of progression-free survival

| Predictor | Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value | Median PFS (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosisa | 44 and older | 1 | Not reached | ||

| 43 and younger | 1.22 | 0.74–2.02 | .428 | 13.4 | |

| Location* | Supratentorial | 1 | 3.9 | ||

| Infratentorial | 0.33 | 0.18–0.63 | .001 | 12.3 | |

| Spine | 0.15 | 0.07–0.31 | <.001 | Not reached | |

| Tumor grade* | Grade II | 1 | 15.8 | ||

| Grade I | 1.90 | 0.73–4.96 | .189 | Not reached | |

| Grade III | 3.00 | 1.45–6.07 | .003 | 2.3 | |

| Initial treatment*,b | GTR | 1 | Not reached | ||

| STR | 2.61 | 1.27–5.36 | .009 | 14 | |

| STR + radiation | 2.44 | 1.36–4.36 | .003 | 11.3 | |

| GTR + radiation | 0.62 | 0.27–1.45 | .271 | 10.8 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GTR + radiation, gross total resection followed by radiation; HR, hazard ratio; STR, subtotal resection followed by observation; STR + radiation, subtotal resection followed by radiation.

aBased on median age.

bInitial treatment variable is categorized as gross total resection followed by observation.

*Significant at P < .05.

Because recent findings suggest that histological features and specific molecular profiles (for subgroups of supra- and infratentorial tumors) differ according to tumor location,18 a separate multivariate Cox proportional hazard model was fitted for each of the 3 tumor locations. In the supratentorial brain region, only initial treatment significantly contributed to PFS. Participants who underwent STR + radiation had a higher risk of progression than those who only underwent GTR (HR = 5.38; 95% CI, 1.78–16.26; P < .01). Although, participants with grade III supratentorial tumors showed a trend towards having a shorter progression-free time than those with grade I tumors, this effect did not reach significance (P < .09).

In the infratentorial brain region, no participants who underwent GTR + radiation had any progression. Therefore, we utilized the Firth penalized method to fit the Cox proportional hazard model.19 It showed that tumor grade and initial treatment were significantly associated with PFS. Adults with grade III infratentorial tumors had a higher risk for progression than those with grade II infratentorial tumor (HR = 7.30; 95% CI, 1.30–29.34; P < .03). Participants who underwent GTR, STR, or STR + radiation also had higher risks of progression than those who underwent a gross total resection followed by radiation. (HR = 12.80; 95% CI, 1.50–1690.44; P < .01; HR = 34.37; 95% CI, 3.69–4658.06; P < .01; HR = 12.12; 95% CI, 1.32–1627.69; P < .03, respectively). The confidence intervals for the HRs are very wide; however, for such complete separation of data (ie, all events occurred in one group). Heinze and Schemper (2001) showed that the inference based on the Firth penalized method is generally valid, although some caution should be executed when interpreting the confidence intervals.19

In the spine region, initial treatment contributed significantly to PFS. The hazard for progression increased more for spine participants who underwent STR + radiation than for those who underwent GTR (HR = 5.01; 95% CI, 1.84–13.69; P < .01). There was no difference in PFS between spine participants who underwent STR and those who underwent STR + radiation (HR = 0.31; 95% CI, 0.07–1.42; P = .13; data not shown) or between spine participants with GTR and GTR + radiation (P < .2). Table 4 presents the prognostic factors by tumor location.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of progression-free survival by tumor location

| Predictor | Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supratentorial brain | ||||

| Age at diagnosisa | ≥37 y | 1 | ||

| <36 y | 0.61 | 0.26–1.44 | .258 | |

| Tumor grade | Grade II | 1 | ||

| Grade III | 2.21 | 0.89–5.48 | .086 | |

| Initial treatment*,b | GTR | 1 | ||

| STR | 1.49 | 0.17–12.75 | .718 | |

| STR + radiation | 5.38 | 1.78–16.26 | .003 | |

| GTR + radiation | 1.39 | 0.5–3.67 | .506 | |

| Infratentorial brainc | ||||

| Age at diagnosis | ≥48 y | 1 | ||

| <47 y | 1.47 | 0.62–3.79 | .384 | |

| Tumor grade* | Grade II | 1 | ||

| Grade III | 7.30 | 1.30–29.34 | .027 | |

| Initial treatment*,b | GTR + radiation | 1 | ||

| GTR | 12.80 | 1.50–1690.44 | .014 | |

| STR | 34.37 | 3.69–4658.06 | <.001 | |

| STR + radiation | 12.12 | 1.32–1627.69 | .023 | |

| Spine | ||||

| Age at diagnosis | ≥45 y | 1 | ||

| ≤44 y | 2.93 | 0.95–9.05 | .061 | |

| Tumor grade | Grade II | 1 | ||

| Grade I | 1.19 | 0.43–3.29 | .742 | |

| Grade III | 1.94 | 0.39–9.64 | .416 | |

| Initial treatment*,b | GTR | 1 | ||

| STR | 1.54 | 0.32–7.55 | .592 | |

| STR + radiation | 5.01 | 1.84–13.69 | .002 | |

| GTR + radiation | 3.84 | 0.46–32.10 | .215 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GTR, Gross total resection followed by observation; GTR + radiation, gross total resection followed by radiation; HR, hazard ratio; STR, subtotal resection followed by observation; STR + radiation, subtotal resection followed by radiation.

aBased on median age.

bInitial treatment variable is categorized as gross total resection followed by observation, subtotal resection followed by observation, subtotal resection followed by radiation, and gross total resection followed by radiation.

cwith Firth's penalized method.

*Significant at P < .05.

Discussion

The data analyzed were generated from the CERN Ependymoma Correlative Tissue Repository, a collaborative multicenter project designed to study the clinical course of patients with ependymoma and its impact on survival. In this preliminary analysis, PFS was impacted by tumor grade, tumor location, and initial treatment.

As previously reported, grade II ependymomas are the most prevalent, and grade III tumors have the worst overall prognosis,2,7,11,13 particularly in both brain regions. However, our study demonstrated that the grade I myxopapillary ependymoma, which is traditionally considered to be a benign tumor, did not have a better outcome than the grade II ependymoma.18 There is ongoing debate in neuropathology on the use of histological features to grade ependymoma, whether myxopapillary ependymoma may actually be a distinct disease, and how to integrate the current WHO grading system with findings from molecular studies.4,18,20–24 Furthermore, there is also the issue of misdiagnosis. In the present study, 7% of participants had an initial nonependymoma diagnosis that was later reclassified as ependymoma, but other studies have reported misdiagnosis to be as high as 15%.7 These reports, coupled with our findings regarding the lack of correlation of grade I and II tumors with outcomes, lend support for the need for molecular classification of these tumors to further refine tumor grade.

Tumor location was also associated with PFS. While previous studies typically focused on ependymomas from a specific location,8,9,14,25,26 our sample size was large enough to include both brain and spine participants. Our results support the previous findings that intracranial ependymoma has an overall worse prognosis compared with spinal cord tumors.2,7,11,13 In addition, we were able to analyze the comparative risk of a supratentorial location to a spine location or an infratentorial location, with supratentorial location being associated with shorter progression-free time then the other locations.

PFS was also associated with treatment at diagnosis. Extent of initial surgery impacted PFS, with less than a gross total resection increasing the risk of early progression for all 3 regions, thus supporting previous reports.14,15 Radiation at the time of diagnosis was found to be beneficial for PFS (with a longer progression-free time) in the infratentorial brain region. None of the participants with infratentorial tumors who received radiation after their initial gross total resection had a progression or recurrence. This is consistent with other studies that strongly support the utility of postoperative radiation, specifically for infratentorial ependymoma regardless of the extent of resection.27 There were no obvious clinical or demographic characteristics (such as tumor grade or age) of these 10 participants that made them distinct from the remainder of the group. Future development of molecular diagnostics and innovative imaging may uncover additional characteristics that cannot be ascribed from a retrospective analysis. For participants with either a supratentorial or spine ependymoma, radiation following a subtotal resection shortened PFS when compared with a gross total resection only. However, it did not make a difference when compared with participants who also had a subtotal resection but no radiation. This may reflect the variability of the clinical decision-making process in which radiation is often reserved for those with an incomplete resection and/or higher tumor grade. The number of high-grade tumors in the spine and supratentorial region was relatively small, and this may account for the wide variance of outcomes and lack of significance on multivariate analysis. Iqbal and Lewis summarized the lack of consensus among researchers regarding the effect of initial radiation treatment on outcome,2 as some studies have shown it to be beneficial15 while others have not.9,14,28

The CERN Ependymoma Correlative Tissue Repository represents a large international collaboration designed to collect clinically annotated tumor tissues from patients with ependymoma. This effort has been very successful in providing materials necessary for understanding the clinical outcomes as well as molecular and pathological correlations as shown by recent publications by Wani et al22 and Raghunathan et al.18 These studies have provided important insights into the clinical course and biology of ependymomas. There are, however, some limitations to the interpretation of these data. The study is retrospective in nature, and most of the analyses are limited to PFS given the overall long survival with ependymoma. For example, in the patient population analyzed in the current study only 49 had died at the time of the analysis. Such a small number of deaths would yield inaccurate survival estimates and thus were not included as part of this analysis. Also, because the participating centers are all tertiary and academic institutions, there may be a bias in the referral pattern of patients included in the study. However, this is balanced with the inclusion of data from a multi-institutional, international dataset. Furthermore, our data collection period included transitions in available technologies and treatments. While these changes may impact the results, the impact would be minimal because only 2 participants were diagnosed before 1980. Lastly, study procedures did not include a central imaging review. All clinical data were determined and provided by the individual participating centers based on their review of the medical record. Despite these limitations, this ependymoma repository represents the largest clinically annotated ependymoma repository in the world. It presents an outstanding opportunity to explore the clinical course and molecular evolution of ependymoma to both improve our understanding of the disease and ultimately identify molecular subtypes distinguishable by molecular biomarkers, which will lead to improved and individualized patient treatment.

The importance of this ependymoma tumor tissue repository is further underscored by the recent seminal discoveries within the subtypes of supratentorial and infratentorial ependymomas. A unique fusion, C11orf-RELA, was recently described in a subset of patients with supratentorial ependymoma.29 This molecular change results in the constitutive activation of the NFKB pathway, is distinct from the tumors without the fusion, and may provide a unique therapeutic target. Additionally, subsets of posterior fossa tumors were recently found to be distinguishable from others by a hypermethylated state of the CPG-islands (CIMP). As with the supratentorial tumors, the CIMP status may provide a specific therapeutic target.30 These discoveries are currently undergoing extensive evaluation utilizing the clinically annotated resource provided by the ependymoma repository. Based on these results and recent advancements in molecular classification, we can explore associations between subgroups, extent of resection, and impact of additional therapies, such as radiation, on the likelihood of tumor progression.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Collaborative Ependymoma Research Network (CERN Foundation).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This report was initially presented at the 2012 Society of Neuro-Oncology Scientific Meeting. We also acknowledge the participation of Biobank Authorization Number 2008/70, AC-2013-1786 and SIRIC Grant INCa-DGOS-Inserm 6038 for Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Marseille (PM).

Conflict of interest statement. Terri S. Armstrong receives research support from Genentech and Merck. Mark R. Gilbert receives research support from Genentech and Glaxo Smith Kline, honoraria from Merck and Genentech, and serves on advisory boards for AbbVie and Genentech. Howard Colman receives honoraria from Merck and serves on advisory boards for Hoffman-La Roche, Genentech and Proximagen.

References

- 1.Gilbert MR, Ruda R, Soffietti R. Ependymomas in adults. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10(3):240–247. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iqbal MS, Lewis J. An overview of the management of adult ependymomas with emphasis on relapsed disease. Clin Oncol (R Cll Radiol) 2013;25(12):726–733. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godfraind C. Classification and controversies in pathology of ependymomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25(10):1185–1193. doi: 10.1007/s00381-008-0804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang HJ, Sohn JH, Han SJ, et al. Multi-disciplinary treatment of a rare pelvic cavity ependymoma. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48(4):719–722. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2007.48.4.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erdogan G, Ozel E, Pestereli HE, et al. Ovarian ependymoma. APMIS. 2005;113(4):301–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong TS, Vera-Bolanos E, Bekele BN, et al. Adult ependymal tumors: prognosis and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(8):862–870. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metellus P, Guyotat J, Chinot O, et al. Adult intracranial WHO grade II ependymomas: long-term outcome and prognostic factor analysis in a series of 114 patients. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(9):976–984. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aizer AA, Ancukiewicz M, Nguyen PL, et al. Natural history and role of radiation in patients with supratentorial and infratentorial WHO grade II ependymomas: results from a population-based study. J Neurooncol. 2013;115(3):411–419. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGuire CS, Sainani KL, Fisher PG. Incidence patterns for ependymoma: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results study. J Neurosurg. 2009;110(4):725–729. doi: 10.3171/2008.9.JNS08117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amirian ES, Armstrong TS, Aldape KD, et al. Predictors of survival among pediatric and adult ependymoma cases: a study using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data from 1973 to 2007. Neuroepidemiology. 2012;39(2):116–124. doi: 10.1159/000339320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amirian ES, Armstrong TS, Gilbert MR, et al. Predictors of survival among older adults with ependymoma. J Neurooncol. 2012;107(1):183–189. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0730-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villano JL, Parker CK, Dolecek TA. Descriptive epidemiology of ependymal tumours in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(11):2367–2371. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldman WB, Clark AJ, Safaee M, et al. Tumor control after surgery for spinal myxopapillary ependymomas: distinct outcomes in adults versus children. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19(4):471–476. doi: 10.3171/2013.6.SPINE12927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh MC, Ivan ME, Sun MZ, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy delays recurrence following subtotal resection of spinal cord ependymomas. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(2):208–215. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collaborative Ependymoma Research Network. www.cern-foundation.org. Accessed July 28, 2014.

- 17.IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows [computer program]. Version 19.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raghunathan A, Wani K, Armstrong TS, et al. Histological predictors of outcome in ependymoma are dependent on anatomic site within the central nervous system. Brain Pathol. 2013;23(5):584–594. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinze G, Schemper M. A solution to the problem of monotone likelihood in Cox regression. Biometrics. 2001;57(1):114–119. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korshunov A, Golanov A, Sycheva R, et al. The histologic grade is a main prognostic factor for patients with intracranial ependymomas treated in the microneurosurgical era: an analysis of 258 patients. Cancer. 2004;100(6):1230–1237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang I, Nagasawa DT, Kim W, et al. Chromosomal anomalies and prognostic markers for intracranial and spinal ependymomas. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19(6):779–785. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wani K, Armstrong TS, Vera-Bolanos E, et al. A prognostic gene expression signature in infratentorial ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(5):727–738. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0941-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor MD, Poppleton H, Fuller C, et al. Radial glia cells are candidate stem cells of ependymoma. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(4):323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman LM, Donson AM, Nakachi I, et al. Molecular sub-group-specific immunophenotypic changes are associated with outcome in recurrent posterior fossa ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(5):731–745. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh MC, Kim JM, Kaur G, et al. Prognosis by tumor location in adults with spinal ependymomas. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;18(3):226–235. doi: 10.3171/2012.12.SPINE12591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dutzmann S, Schatlo B, Lobrinus A, et al. A multi-center retrospective analysis of treatment effects and quality of life in adult patients with cranial ependymomas. J Neurooncol. 2013;114(3):319–327. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers L, Pueschel J, Spetzler R, et al. Is gross-total resection sufficient treatment for posterior fossa ependymomas? J Neurosurg. 2005;102(4):629–636. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.4.0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghia AJ, Mahajan A, Allen PK, et al. Supratentorial gross-totally resected non-anaplastic ependymoma: population based patterns of care and outcomes analysis. J Neurooncol. 2013;115(3):513–520. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker M, Mohankumar KM, Punchihewa C, et al. C11orf95-RELA fusions drive oncogenic NF-kappaB signalling in ependymoma. Nature. 2014;506(7489):451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature13109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mack SC, Witt H, Piro RM, et al. Epigenomic alterations define lethal CIMP-positive ependymomas of infancy. Nature. 2014;506(7489):445–450. doi: 10.1038/nature13108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.