Abstract

Background

Malignant glioma is an aggressive cancer requiring new therapeutic targets. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) regulate gene expression post transcriptionally and are implicated in cancer development and progression. Deregulated expressions of several miRNAs, specifically hsa-miR-184, correlate with glioma development.

Methods

Bioinformatic approaches were used to identify potential miR-184-regulated target genes involved in malignant glioma progression. This strategy identified a multifunctional nuclease, SND1, known to be overexpressed in multiple cancers, including breast, colon, and hepatocellular carcinoma, as a putative direct miR-184 target gene. SND1 levels were evaluated in patient tumor samples and human-derived cell lines. We analyzed invasion and signaling in vitro through SND1 gain-of-function and loss-of-function. An orthotopic xenograft model with primary glioma cells demonstrated a role of miR-184/SND1 in glioma pathogenesis in vivo.

Results

SND1 is highly expressed in human glioma tissue and inversely correlated with miR-184 expression. Transfection of glioma cells with a miR-184 mimic inhibited invasion, suppressed colony formation, and reduced anchorage-independent growth in soft agar. Similar phenotypes were evident when SND1 was knocked down with siRNA. Additionally, knockdown (KD) of SND1 induced senescence and improved the chemoresistant properties of malignant glioma cells. In an orthotopic xenograft model, KD of SND1 or transfection with a miR-184 mimic induced a less invasive tumor phenotype and significantly improved survival of tumor bearing mice.

Conclusions

Our study is the first to show a novel regulatory role of SND1, a direct target of miR-184, in glioma progression, suggesting that the miR-184/SND1 axis may be a useful diagnostic and therapeutic tool for malignant glioma.

Keywords: intracranial injection, invasion, malignant glioma, miR-184, SND1

Malignant gliomas are the most frequent malignant brain tumor in adults.1 Despite multimodality therapies including surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, the prognosis for malignant glioma remains extremely poor.2 The rapid growth and highly invasive nature of malignant glioma favor its infiltration into surrounding normal brain parenchyma and facilitate recurrence after therapy.3 The aggressive progression of this disease requires an improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying and supporting tumor-cell survival and invasion.

MicroRNAs (miRs) are short, noncoding RNAs, approximately 18–24 nucleotides in length, that negatively regulate the expression of multiple target genes.4 miRs are involved in post-transcriptional gene regulation, which have been shown to modulate tumor cell proliferation and apoptosis and to act as oncogenes or tumor-suppressor genes.5 Numerous studies have provided evidence that miRs play prominent roles in cancer genesis, prognosis, diagnosis, and therapy.6 Recent studies have demonstrated that the levels of distinct miRs in the glioma environment differ from those in peritumoral tissue.7–9 Recently Malzkorn et al explored the role of miRNAs in the malignant progression of human gliomas by comparing miRNA expression profiles in primary low-grade gliomas and secondary high-grade gliomas from individual patients.8 They identified miR-184, whose expression was reduced with disease progression. A study by Ma et al also reported a negative correlation of miR-184 expression with glioma grade.7 Although miR-184 reportedly plays an important role in the progression of malignancy in glioma, no functional target of miR-184 in glioma has been validated in detail.

SND1, also known as p100 and Tudor-SN, is a highly conserved protein from yeast to humans suggested to be involved in the regulation of gene expression, including transcription and pre-mRNA splicing, as well as translation and RNA interference.10 SND1 was originally identified as a protein interacting with the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2), and promoting EBNA2-dependent transcription.11 The protein was also reported to interact with some transcriptional regulators, including c-Myb, STAT5 and STAT6, suggesting its biological role as a transcriptional coactivator.12,13 Recently, 2 studies reported that SND1 is one of the components of RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and that disruption of SND1 causes defects in siRNA-mediated gene silencing.14,15 Although the biological function of SND1 is not fully elucidated, these intriguing findings suggested the possible involvement of SND1 as a key regulator for gene expression at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels.

Recent studies indicate that SND1 is overexpressed in human tumors such as breast, colon, prostate, and hepatocellular carcinomas. Proteomic profiling identified high SND1 expression in metastatic breast cancer cells and also in tumor samples from metastatic breast cancer patients.16 SND1 is overexpressed in human colon cancers, and overexpression of SND1 in rat intestinal epithelial cells resulted in loss of contact inhibition and promoted cell proliferation via activation of the Wnt signaling pathway.17 SND1 overexpression has been detected in prostate cancer, and siRNA inhibition of SND1 has been reported to decrease viability of prostate cancer cells.18 A recent study from our group documented that SND1 interacts with the oncogene astrocyte elevated gene 1 (AEG-1) in RISC and that SND1 is overexpressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).14 Although SND1 is known to regulate tumor growth in multiple cancer contexts, its role in malignant glioma progression has not been previously explored.

In this study, we confirmed that miR-184 is appreciably downregulated in human malignant glioma cells and tumor tissue as compared with their normal cellular counterpart. We identified SND1 as a downstream target of miR-184, and KD of SND1 or overexpression of miR-184 significantly modulated malignant glioma progression by affecting cell survival, invasion, and chemoresistance. This is the first report that definitively establishes SND1 as a downstream target of miR-184 and provides a novel target for glioma therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines, Cell Culture, Human Tissue Samples, and Tissue Microarray

Cell lines and tissue microarray (TMA) are described in Supplementary methods. Specimens of human primary brain tumors were collected from participants who underwent surgical removal of their brain tumor at the Department of Neurosurgery, New York Presbyterian Hospital, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. All participants were informed of the nature and requirements of the study and provided written consent to donate their tissues for research purposes. Tumor specimens of all histological types and grades of primary brain tumors were collected, snap-frozen, and stored in the tumor bank following the protocol approved by Columbia University institutional review board.

Antibodies and Chemicals

Rabbit anti-SND1 polyclonal antibody has been described before.19 Actin antibodies were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. The SND1 antibody used in immunohistochemistry was obtained from Abgent, Ki-67 and MBD1 antibodies were obtained from AbCam, and the rest of the antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. Temozolomide (TMZ) was purchased from TOCRIS Bioscience. Lipofectamine from Invitrogen was used as the transfection reagent in all experiments.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescent Staining

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence on TMA slides and tissue sections was performed as previously described20 (described in Supplementary methods).

Plasmid Constructions, Transfections, and Stable Clone Generation

SND1 expression vector in pCMV6-ENTRY with C-terminal Myc and FLAG tags was obtained from Origene Technologies. The shRNAs, designed to knock down SND1, were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. miR-184 expression plasmid was purchased from GeneCopoeia. Stable clone generations are described in Supplementary methods.

Cell Invasion Assays

Cell invasion capacity was assessed using the Cell Invasion Assay Kit (BD Biosciences) according to manufacturer's instruction (described in Supplementary methods).

Western Blotting

Preparation of whole-cell lysates and Western blotting analysis were conducted following standard protocols as described earlier.21

Colony Formation Assays in Monolayer

Stably transfected cells were plated in triplicate at low density for determining formation of single-cell colonies in 6-well plates. Cells were cultured in the presence of appropriate complete medium for 2 weeks. Plates were then stained with 0.5% crystal violet and photographed, and the colonies were counted. Data represent the mean ± SD of duplicate experiments.

Soft Agar Colony Formation Assays

Anchorage-independent growth assays were performed by seeding 2 × 105 cells suspended in 0.3% base agar in the 6-well plates coated with 0.6% base agar. Colonies were counted 14 days after seeding and analyzed using Image J colony counter (NIH). The data from triplicate wells were expressed as mean ± SD.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Apoptotic assays were performed using an FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Flow cytometric assays were performed using FACS Canto (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FACSDIVA software.

Mutation of hsa-miR-184 Binding Site in the 3′UTR of SND1 and Luciferase Assay

The hsa-miR-184 binding site in the 3′UTR of SND1 (GeneCopoeia) was mutated using the QuickChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) according to manufacturer's instructions. Luciferase assay was conducted as described previously.22

Intracranial Implant of GBM6 Cells in Mice and Survival Experiments

Using a stereotaxic frame, control shRNA, SND1 shRNA (SND1-SH), and miR-184 transfected stable GBM6 cells (10 000 cells in 2 µl PBS) were intracranially injected into athymic nude mouse brains with the coordination of 2.5 mm lateral, 0.4 mm frontal of bregma and 3.5 mm deep from skull. Animals of each group were monitored until they reached the point of euthanization according to the Virginia Commonwealth University-IACUC approved protocol. Survival data were collected and analyzed with Prism 5.

Statistics

All in vitro experiments were repeated at least in triplicate with 2 independent replicates. Animal number 5 was used in survival tests. Statistical analyses were calculated using 1-way and 2-way ANOVA for grouped samples, followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test; and the 2-tail Student t test was used for comparison between control and treatment groups. P values were 2 sided, and all confidence intervals were at the 95% level. Computation for all analyses was conducted using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS).

Results

miR-184 is Downregulated in Glioma Cell Lines and Glioma Tissues, and Overexpression of miR-184 Inhibits Growth and Invasion of Glioma Cells

Previously, miR-184 was shown to be downregulated in glioma tissue as compared with normal brain.7,8 To confirm these results, we analyzed miR-184 expression in glioma cell lines and glioma tissues. Real-time PCR analyses showed that expression of miR-184 was markedly lower in all analyzed glioma cell lines, including U87, T98G, H4 and a primary glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cell line (GBM6), as compared with those in IM-PHFA cells (Supplementary Fig. S1A). To determine whether miR-184 downregulation in glioma cell lines was also clinically relevant, we further examined the miR-184 expression in 10 glioma tissues and 5 normal brain tissues. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1B, comparative analysis showed that the expression level of miR-184 was significantly reduced in tumor tissues as compared with that in normal brain tissues. To understand the biological significance of miR-184 downregulation in glioma, we stably overexpressed miR-184 in GBM6 cells (Supplementary Fig. S1C). Overexpression of miR-184 significantly lowered invasion and colony formation in GBM6 cells (Supplementary Fig. S1D) as compared with control (Con) mimic-treated cells. These results confirmed that miR-184 plays a tumor suppressor role in malignant glioma.

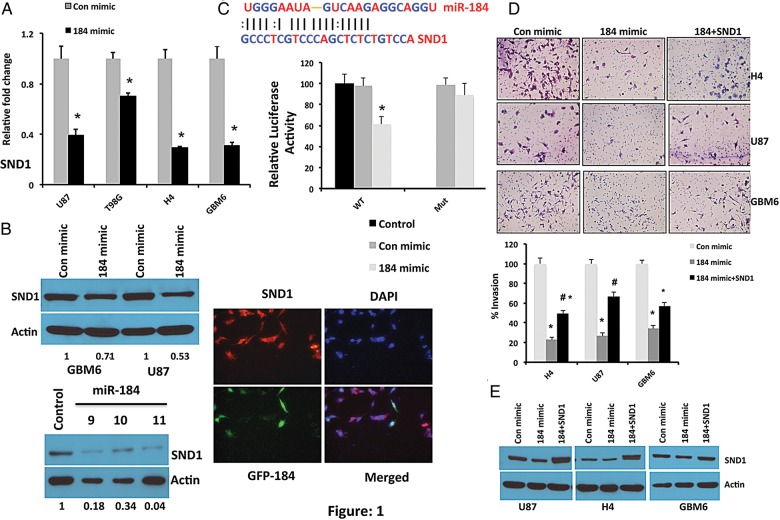

miR-184 Downregulates SND1 by Potentially Targeting Its 3′-UTRs

To determine the function of miR-184, 2 computational algorithms, miRANDA and DIANA-microT, were used to search for potential miR-184 target genes (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Although a large number of different target genes were predicted, we focused on SND1, which was projected by both of the algorithms. A miR-184-binding site was found in the 3′-UTR of SND1 mRNA (Fig. 1). For overexpression of miR-184, we used miR-184 mimic in several glioma cells and validated expression by quantitative PCR (Supplementary Fig. S2). As predicted, upregulation of miR-184, either by transient or stable overexpression, significantly decreased the expression level of SND1 mRNA in multiple glioma cells (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. S3). This observation was further confirmed at the protein level by Western blotting analysis in several glioma cells as shown in Fig. 1B. Furthermore, we found that overexpression of miR-184 significantly reduced the luciferase activity of SND1-3′UTR (Fig. 1C). However, miR-184 overexpression did not alter the luciferase activity of the SND1-3′UTR-mutant, containing mutations in the miR-184-binding seed region of SND1-3′UTR (Fig. 1C), suggesting that miR-184 potentially targets the 3′UTR of SND1.

Fig. 1.

miR-184 significantly downregulates SND1 by potentially targeting its 3′-UTR. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of SND1 in multiple glioma cell lines including U87, T98G, H4, and GBM6 following transfection of either Con mimic or miR-184 mimic. RNA was isolated at 48 hours after transfection. The average SND1 expression was normalized to GAPDH and presented as relative fold-changes. *P < .05 compared with Con mimic. (B) Upper panel, Western blotting analysis of SND1 in U87 and GBM6 cells following transient transfection of either Con mimic or miR-184 mimic. Protein was isolated 48 hours after transfection. Lower panel, SND1 level analyzed by Western blotting in GBM6 cells stably transfected with miR-184. Actin was used as loading control. Right panel, immunofluorescence staining of SND1 (red) in GBM6 cells stably overexpressing GFP-miR-184 (green). Note that the green cells express low levels of SND1 as compared with the non-GFP-expressing cells. Correlation score of red and green is 0.157. Scale bar, 50 μM. (C) Luciferase assay of GBM6 cells transfected with the SND1-3′UTR reporter (WT) or the SND1-3′UTR mutant (Mut) reporter with Con mimic or miR-184 mimic or mock control. *P <.05 compared with mock control (basal). Bar represents the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (D) miR-184 significantly inhibits the invasive ability of glioma cells, which can be rescued by overexpression of SND1. Matrigel invasion assay of H4, U87, and GBM6 cells after transfecting with Con mimic, miR-184 mimic, or combination of miR-184 mimic with SND1. Upper panel, representative images of invasion assay. Lower panel, quantification of invaded cells. *P < .05 versus Con mimic; #P < .05 versus 184 mimic. (E) Western blotting analysis of SND1 in Con mimic, miR-184 mimic, or combination of miR-184 mimic with SND1-transfected cells. Cell lysates were collected at 48 hours after transfection. Actin was used as loading control.

To further investigate the role of SND1 repression in miR-184-induced decreased glioma progression, we examined the effects of SND1 reintroduction on glioma cell invasion. As shown in Fig. 1D and E, reintroduction of SND1 in miR-184-transfected cells rescued, at least partially, miR-184-mediated decreased glioma cell invasion. Taken together, our results suggest that SND1 is a genuine target of miR-184 and that SND1 downregulation contributes to miR-184-mediated invasion suppression in glioma cells.

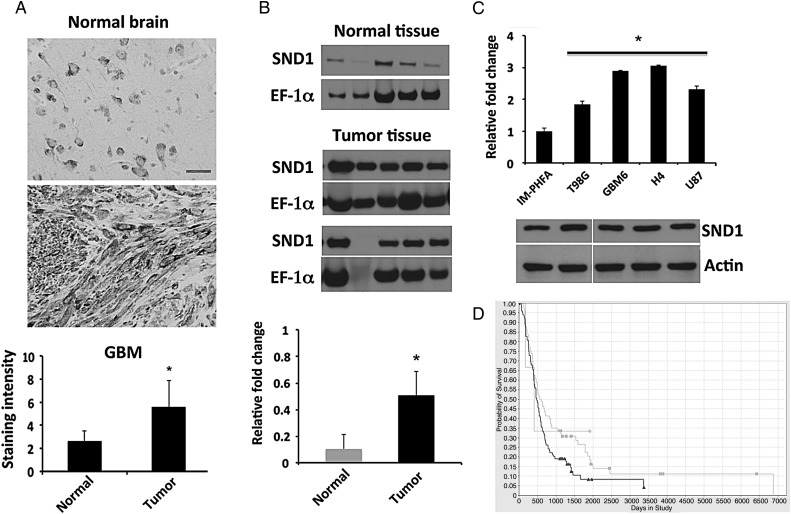

SND1 is Upregulated in Human Glioma and Regulates Glioma Progression

Given the increased expression of SND1 observed in HCC, colorectal and prostate cancer, we determined if similar trends were evident in human glioma. SND1 protein levels were determined by immunohistochemical staining in a TMA containing GBM and normal brain tissues. As shown in Fig. 2A, SND1 is predominantly detected in the cytoplasm, and SND1 expression is significantly elevated in tumor tissue as compared with normal brain tissue. Protein expression of SND1 was also verified by Western blotting in 10 specimens from surgically removed primary brain tumors. When compared with samples obtained from normal brain tissue (n = 5), which show low but detectable levels, tumor tissue more frequently showed high expression of SND1 (Fig. 2B). We also analyzed the TCGA dataset and it showed a similar trend of high SND1 expression in human astrocytoma and glioblastoma samples as compared with normal brain (Supplementary Fig. S4). Cell lines used in vitro were then analyzed for SND1 expression level by quantitative PCR and Western blotting analyses. SND1 levels were significantly elevated in glioma cells as compared with IM-PHFA cells (Fig. 2C). To determine the clinical relevance of SND1 in glioma, we analyzed data from the Repository for Molecular Brain Neoplasia Data (REMBRANDT). The glioma patients were analyzed according to SND1 copy number (amplified [n = 99], intermediate [n = 80], deleted [n = 3]). The resulting Kaplan-Meier plot (Fig. 2D) clearly indicated that a high SND1 level is associated with poor survival (P < .0298) in log-rank tests. However, we could not find any significant difference between the SND1 deleted versus intermediate or deleted versus high SND1 group. These results suggest that SND1 is upregulated in glioma and represents a clinically relevant molecule in glioma.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of SND1 expression in glioma tissues and cell lines. (A) SND1 detected by immunohistochemistry in a human glioma tissue microarray; scale bar, 50 μM. Lower panel, bar graph shows staining intensity quantified by 3 independent investigators. (B) The expression of SND1 was examined in primary glioma tissues including astrocytoma and GBM (Tumor) and normal brain (Normal) from 5 individual patients in each group. EF-1α was used as loading control. Lower panel, densitometric values of SND1 normalized by EF-1α. *P < .05 compared with normal brain. (C) SND1 expression at RNA level (upper panel) and protein level (lower panel) was analyzed in IM-PHFA and glioma cell lines including T98G, GBM6, H4, and U87. The average SND1 mRNA was normalized to GAPDH and expressed as relative fold-changes. *P < .05 compared with IM-PHFA. (D) Improved survival of patients in intermediate SND1 group (light gray line, n = 80) as compared with SND1 amplified group (dark gray line, n = 99). Data source: https://caintegrator.nci.nih.gov/rembrandt/kmGraph.do?method=redrawKMPlot.

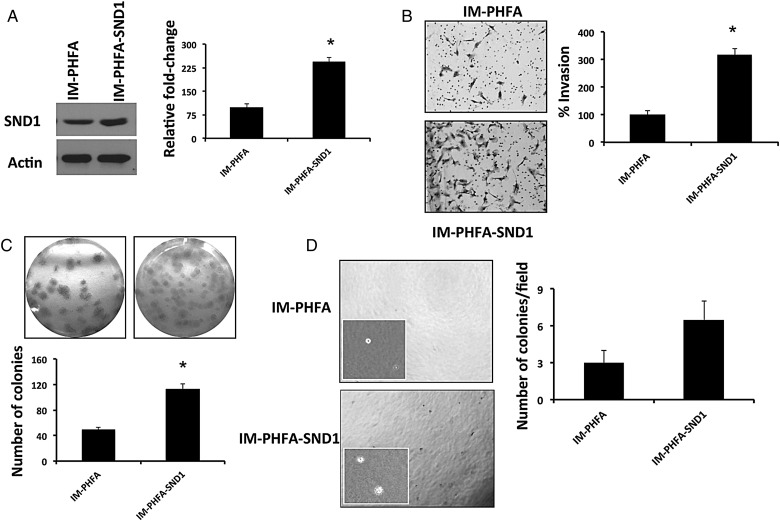

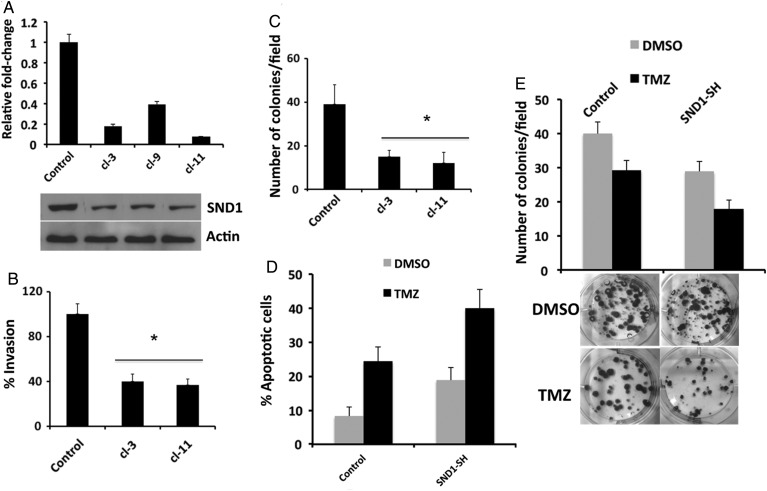

To define the functional role of SND1 in glioma pathogenesis, we either overexpressed SND1 in IM-PHFA cells (low SND1) or knocked down SND1 in T98G or GBM6 cells (high SND1). IM-PHFA-SND1 cells demonstrated a significant increase in invasion and colony formation as compared with parental IM-PHFA cells (Fig. 3). Conversely, when SND1 was knocked down in T98G (Supplementary Fig. S5) or GBM6 (Fig. 4) cells, it significantly decreased invasion and colony formation both in monolayer and in soft agar.

Fig. 3.

Stable overexpression of SND1 in IM-PHFA cells significantly enhances invasion (B), colony formation in monolayer culture (C), and in soft agar (D). *P < .05.

Fig. 4.

Stable KD of SND1 recapitulates the biological phenotype observed following overexpression of miR-184. (A) Real time PCR (upper) and Western blotting analysis of SND1 in SND1-knocked down GBM6 cells. Actin was used as a loading control in Western blotting assays. (B and C) KD of SND1 significantly inhibits invasion (B) and colony formation (C) in GBM6 cells. *P < .05 compared with control. (D and E) KD of SND1 improves the chemoresistance in primary glioma cells. Control or SND1-SH GBM6 cells were treated with 200 μM of TMZ. Apoptosis (D) was quantified by Annexin V-APC at 72 hours after treatment. Colonies (E) were quantified at 2 weeks after treatment, as described in Materials and Methods section.

Next, we examined the effect of inhibition of SND1 on chemoresistance in primary GBM cells by combining KD of SND1 with TMZ, an FDA-approved drug used with radiation therapy as a standard of treatment for GBM patients. We used primary glioma cells (GBM6) because its phenotype is more indicative of the clinical situation than many established glioma cell lines. TMZ is a DNA-damaging agent, which is known to cause glioma cell death by inducing apoptosis and autophagy. We speculated that combination treatment of TMZ and targeting multifunctional SND1 in glioma cells could result in an enhanced effect in decreasing glioma tumor progression. To study the effect of SND1 KD plus TMZ treatment on glioma cell apoptosis, we performed flow cytometric analysis in GBM6 cells transfected either with control shRNA or SND1 shRNA. Both TMZ and SND1 KD alone increased the apoptotic cell population from 8.2% to 24.3% and 18.8%, respectively (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, combination treatment of SND1 KD and TMZ enhanced the population of apoptotic cells to 39.9%. A similar trend was seen in colony formation assays (Fig. 4E). Collectively, these results suggest that SND1 plays an important role in glioma cell survival and invasion and that loss of SND1 expression improves chemoresistance of primary glioma cells.

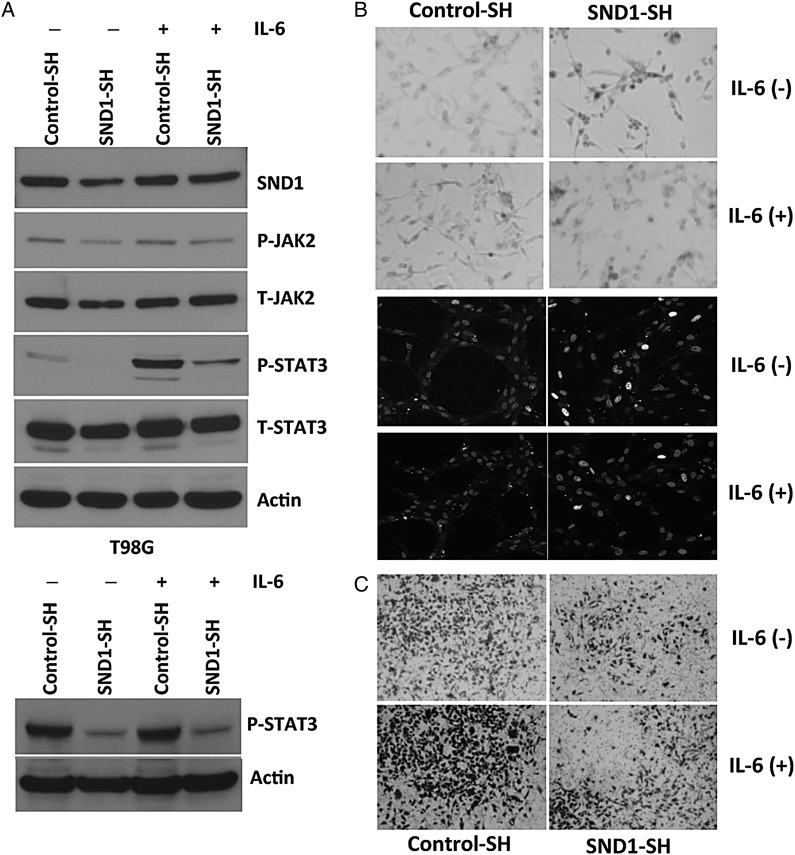

Knockdown of SND1 Induces Senescence in a STAT3-Dependent Manner

Activation of STAT3 is linked to the aggressive nature of malignant glioma.23,24 STAT3 was found to be constitutively active and regulate several key features of gliomagenesis including proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion/migration, and chemoresistance.24 Accordingly, we tested whether SND1 KD altered STAT3 activation in glioma cells, and interestingly we found that KD of SND1 strongly decreased STAT3 (Tyr705) phosphorylation in malignant glioma cells (Fig. 5A). SND1 knocked-down T98G cells also showed reduced amounts of the STAT3-specific kinase JAK2, an upstream activator of STAT3. Another intriguing observation is when SND1 was knocked down in U87 malignant glioma cells; a significant proportion of the cells changed to a flat morphology, and these cells stained positive with beta-galactosidase, indicating induction of cellular senescence (Fig. 5B). This observation was confirmed by H2AX staining, which showed foci formation in the senescent cells (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, when STAT3 was reactivated in malignant glioma cells by IL-6 stimulation, cellular senescence was diminished in the SND1 knocked-down malignant glioma cells (Fig. 5B). Recent studies have linked STAT3 to metastatic progression of cancer, and the contribution of STAT3 to metastatic progression occurs through a variety of molecular mechanisms.24,25 For example, STAT3 activation regulates the expression of matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-1, which then mediate tumor invasion and metastasis.26 Our earlier observations indicated that silencing SND1 in malignant glioma significantly impaired their invasive ability. To understand the role of STAT3 regulation by SND1 in the invasive ability, we performed Matrigel invasion assays in control cells and SND1-SH-treated primary glioma cells following stimulation with IL-6 to reactivate STAT3. As shown in Fig. 5C, knocking down of SND1 significantly abrogated the basal, and IL-6-induced invasive ability of primary human GBM cells. These results suggest that JAK-STAT3 inhibition is an important event in SND1-mediated senescence and invasion in malignant glioma.

Fig. 5.

SND1 facilitates glioma progression by decreasing senescence and increasing invasion. (A) KD of SND1 dramatically inhibits STAT3 phosphorylation in T98G and U87 cells. (B) Knockdown of SND1 promotes senescence-induced cell death. Reactivation of STAT-3 by IL-6 partly abrogates the SND1-mediated senescence phenotype. Upper panel, beta- galactosidase assay; lower panel, γ-H2AX staining. (C) KD of SND1 significantly decreases invasion by STAT-3-dependent pathway that can be partially rescued by IL-6-mediated STAT-3 reactivation in glioma cells.

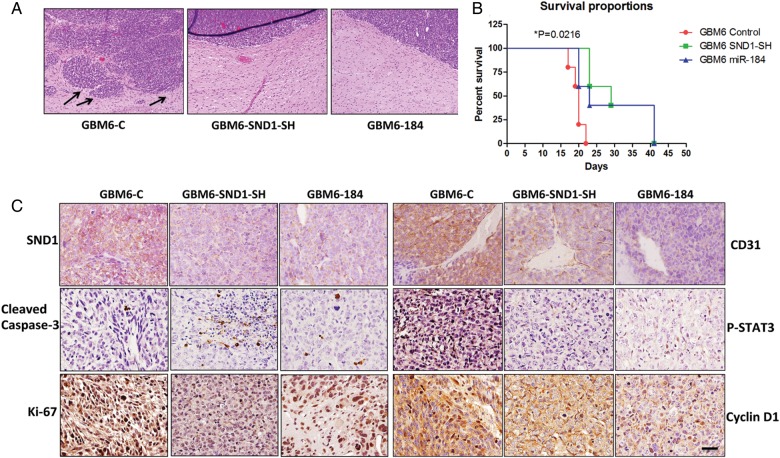

Overexpression of miR-184 or Knockdown of SND1 Inhibits Glioma Invasion in Vivo and Improves Survival of Tumor-bearing Mice

To provide an authentic tumor microenvironment and to further explore the role of miR-184/SND-1 in invasion, we employed an orthotopic xenograft model in which 10 000 cells were stereotactically injected intracranially into athymic nude mice. The mice were monitored for neurological symptoms such as paralysis, seizures, weight loss, and lethargy and were euthanized according to an IACUC-approved protocol. Noteworthy differences were seen in the invasion patterns of tumors formed from GBM6 control cells and tumors from GBM6 SND1-SH or GBM6 miR-184 cells. GBM6 control tumors had more irregular tumor boundaries and showed distinct migration away from the primary tumor, whereas both the GBM6 SND1-SH and miR-184 tumors demonstrated well-circumscribed tumor margins (Fig. 6A). The survival times for the GBM6-SND1-SH and GBM6-miR-184 group were significantly longer when compared with the GBM6 control group by chi-square analysis (P = .0216) (Fig. 6B). Postmortem, brain and tumor tissue were collected and sectioned for immunohistochemical staining. GBM6 SND1-SH and miR-184 tumors retained a lower level of SND1 expression than GBM6 control tumors (Fig. 6C and Table 1). GBM6-control tumors showed enhanced Ki-67, P-STAT3, and CyclinD1, and low cleaved caspase 3 expressions compared with GBM6 SND1-SH and miR-184 tumors (Fig. 6C and Table 1). Additionally, GBM6-control tumors exhibited substantially greater CD31 expression compared with GBM6 SND1-SH and miR-184 tumors, supporting a role for SND1 in angiogenesis, as described earlier in HCC.19

Fig. 6.

Stable expression of miR-184 or KD of SND1 decreases in vivo glioma invasion and improves survival in nude mice. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of mice brains from GBM6-control, GBM6 SND1-SH, and GBM6 miR-184 group. Note the highly invasive tumor margin in the control group indicated by arrows. (B) Survival time for mice injected with GBM6 control, GBM6 SND1-SH, and GBM6 miR-184 cells. In both SND1-SH and miR-184 group, the survival is significantly improved versus control mice. P = .0216. (C) SND1, Ki-67, cleaved caspase 3, CD31, P-STAT3 and cyclinD1 expression in brain sections from GBM6 control, GBM6 SND1-SH, and GBM6 miR-184 mice. Scale bar, 50 μM.

Table 1.

Quantification analysis of immunohistochemistry staining of SND1, CD31, Ki67, cleaved caspase 3, P-STAT3, and cyclinD1 in tumor sections expressed as mean density

| Protein | GBM6-C | GBM6-SND1-SH | GBM6-184 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SND1 | 2.395 ± 0.263 | 0.395 ± 0.021* | 0.54 ± 0.1* |

| CD31 | 4.72 ± 0.59 | 0.95 ± 0.35* | 1.89 ± 0.28* |

| Ki-67 | 7.2 ± 1.16 | 0.71 ± 0.069* | 2.856 ± 1.86* |

| Cleaved caspase 3 | 0.15 ± 0.025 | 1.96 ± 0.124* | 1.13 ± 0.06 |

| P-STAT-3 | 2.22 ± 0.71 | 0.54 ± 0.09* | 0.89 ± 0.98 |

| CyclinD1 | 7.62 ± 1.43 | 2.3 ± 1.29* | 2.86 ± 0.40* |

*Indicates P < .05 versus GBM6-C.

Discussion

The current study provides new insights into the tumor suppressor role of miR-184, which contributes to glioma growth and invasion by targeting SND1. Key findings of this study indicate that SND1 may provide a genuine novel target for malignant glioma treatment. miR-184 expression is significantly downregulated in glioma tissue and cell lines, and ectopic expression of miR-184 decreases the proliferation and invasion of glioma cells through direct regulation of SND1. In contrast, SND1 is significantly upregulated in human malignant glioma tissue and cells as compared with normal brain. REMBRANDT data support the prognostic significance of SND1 expression in which patients with intermediate levels of SND1 survived longer than patients showing elevated SND1 expression. Finally, evidence is provided for a novel regulatory role of SND1 on STAT3 in mediating glioma invasion and senescence-induced cell death.

Numerous studies have suggested that miRNAs are aberrantly expressed in diverse types of cancers, and a detailed understanding of the genes targeted by these miRNAs may help identify novel targets for cancer treatment and therapeutics. miR-184 is downregulated in various types of cancer including neuroblastoma, malignant glioma, prostate cancer, oral cancers, and others.7,8,27–29 In contrast, an increased expression of miR-184 with increasing Gleason scores has been observed in prostate cancer.30 miR-184 was strongly upregulated in tongue squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and its inhibition led to decreased cell proliferation.31 In malignant glioma, we found that miR-184 is significantly downregulated, which is consistent with other studies by Malzkorn et al and Ma et al7,8 Previous studies indicate cell type-specific effects when miR-184 is overexpressed (ie, overexpression of miR-184 in neuroblastoma cell lines decreased proliferation and induced apoptosis),27 while inhibition of miR-184 in SCCs only decreased proliferation.31 We showed that ectopic expression of miR-184 significantly downregulates the growth and invasion of malignant glioma cells both in vitro and in vivo. These functional effects correlate with the in vitro data reported by Malzkorn et al, where they showed that overexpression of miR-184 in A172 and T98G glioma cells significantly decreased cell viability, proliferation, and invasion. Regarding miR-184 targets, possible regulation of AKT2,27 c-Myc,31 and miR-20532 has been reported. A recent paper described the epigenetic regulation of miR-184 by Methyl-CpG binding protein 1 (MBD1) in neural stem cells.33 To determine if similar regulation occurs in glioma, we first compared the expression of MBD1 and SND1 in normal brain and glioma groups. Our data suggest that MBD1 is dramatically upregulated in human glioma samples as compared with normal brain. KD of MBD1 in glioma cells using siRNA resulted in a modest upregulation of miR-184 expression as compared with control siRNA-treated glioma cells (Supplementary Fig. S6). Future studies will investigate this epigenetic regulation in details.

We employed bioinformatic assays to find putative targets of miR-184 and identified SND1 as one potential target. We validated SND1 as being significantly downregulated in multiple glioma cells after transfection with miR-184 mimics. SND1 was previously identified as a transcription-activity enhancer34 and also as an essential protein in B lymphocyte growth. SND1 was shown to bind to c-Myb, a differentiation and growth factor of immature hematopoietic cells and lymphocytes, suggesting involvement in upregulation of translation.10 Several observations also link SND1 to carcinogenesis; however, little is known about the role of this protein in malignant glioma pathogenesis. Tsuchiya et al17,35 reported that SND1 is highly expressed in human colon cancers and chemically induced colon cancers in animals, with SND1 suppressing the adenomatous polyposis coli levels via a post-transcriptional mechanism. In prostate cancer, although SND1 could contribute to the RNA degradation observed in RNA interference, the target RNA was not defined. A previous proteomic profiling identified high SND1 expression in metastatic breast cancer cells and in tumor samples from metastatic breast cancer patients.16 Increased SND1 activity in the RISC complex was found to correlate with the degradation of tumor-suppressor mRNAs by oncogenic miRNAs, thereby facilitating the development of hepatocellular carcinoma.14 In the current study, we found higher SND1 mRNA and protein in human malignant glioma tissue as compared with normal brain tissue. Furthermore, we discovered that SND1 is a clinically relevant molecule in malignant glioma by employing REMBRANDT data analysis because the high SND1 group of patients exhibited worse prognosis than the intermediate group (Fig. 2). Our results also suggest that SND1 plays a crucial role in malignant transformation of glioma by regulating cellular growth and invasion both in vitro and in vivo, facilitating chemoresistance and diminishing senescence-induced cell death. The observation that SND1 regulates several important determinants of glioma progression supports the rationale for using SND1-inhibition as a means of treating glioma patients. A known inhibitor (3′, 5′-deoxythymidin, bisphosphate) of SND1 enzymatic activity is currently available;15 however, the clinical utility is questionable because it works at a high micromolar concentration. Thus, developing clinically relevant small-molecule inhibitors of SND1 is of great potential interest.

According to recent reports, the contributions of SND1 to carcinogenesis may be associated with several signaling pathways: NF-κB signaling in HCC,19 indirect activation of Wnt/β-catenin in colorectal cancer,17 and regulation of microRNA-mediated gene silencing by interacting with AEG-1 in HCC.14 It was also reported that SND1 contributes to tumor angiogenesis by facilitating the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, which in turn allows the expression of genes involved in neovascularization.19 Consistent with a former report,19 neovascularization was greatly reduced in tumor sections of both SND1-SH- and miR-184-treated mice when compared with control mice (Fig. 6C).

A key finding of our present study relates to the regulatory role of SND1 in glioma invasion, which is a major determinant of glioma aggressiveness and directly contributes to the pathogenicity of this deadly cancer. Our results suggest that direct KD of SND1 and indirect silencing of SND1 by miR-184 significantly abrogates cellular invasion in multiple glioma cells. Additionally, KD of SND1 dramatically halts the invasive nature of a primary GBM cell line in an orthotopic xenograft model in mice brains. However, we have noticed a varying degree of invasive ability with the altered expression of SND1. For example, combined transfection of miR-184 and SND1 in U87 and H4 has much higher SND1 compared with the non-transfected control, but the invasive phenotype is less. Similarly in GBM6 cells, there is a clear change in the invasion phenotype, but the change in SND1 expression is marginal (Fig. 1). This could be due to the inherent heterogeneous nature of the various glioma cell lines used in our study. To define the downstream effector molecules of SND1 relevant to glioma invasion, we analyzed the JAK-STAT pathway. Activated STAT-3 in malignant glioma is known to promote cell migration/invasion, anti-apoptosis, drug resistance, angiogenesis, and evasion of antitumor immunity.24,36 Our results indicate that knocking down SND1 significantly inhibits the invasion capacity of glioma cells, which can be abrogated by reactivation of STAT3 by IL-6 stimulation. This is consistent with the previous reports showing the relevance of STAT3 in glioma invasion and MMP expression.23,25,26 Another intriguing observation is the regulatory role of SND1 in cellular senescence. Silencing of SND1 induces senescence-induced cell death that was rescued by STAT3 reactivation. The present results are in agreement with another study from Zhang et al in which the authors show that GADD45G induces HCC cell senescence and that downregulation of the JAK/STAT pathway is the key mediator of GADD45G-induced cell senescence.37

Several important questions related to SND1's role in gliomagenesis need to be addressed in future studies. For example, what is the mechanism of SND1-induced STAT3 activation? Previous reports indicated that as a coactivator SND1 facilitates transcriptional activity of STAT5 and STAT6,12 but its regulatory role on STAT3 in glioma is novel and requires further investigation. SND1 interacts with and associates with the oncogene AEG-1 in HCC, breast cancer, and colon cancer,14,38,39 and AEG-1 is a crucial regulator of malignant glioma,20,40 so investigating the cross talk between these 2 molecules could lead to defining novel roles in the pathogenesis of malignant glioma. Since SND1 regulates several mRNAs and miRNAs in prostate, HCC, and other cancers,34 it would be interesting to define additional SND1 downstream miRNAs that may be relevant to malignant glioma.

In summary, the current study provides the first evidence of an important link between miR-184 and SND1 regulation in human glioma. Experiments confirm the reported tumor suppressor function of miR-184 in malignant glioma, identify SND1 as a novel clinically relevant molecule in malignant glioma, and demonstrate the role of SND1 in regulating glioma progression. However, hurdles remain in establishing a miRNA-based therapeutic approach in the clinic due to the inherent challenges associated with the efficient delivery and stability of miRNAs. In this context, the presence of a potential drugable enzymatic domain strongly supports SND1 as a promising target for glioma therapy.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Support was provided in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01 CA134721 (P.B.F.) and R01 CA138540 (D.S.), the James S. McDonnell Foundation (D.S.), NCI Cancer Center Support Grant to VCU Massey Cancer and VCU Massey Cancer Center developmental funds (P.B.F.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

D.S. is a Harrison Scholar in the VCU Massey Cancer Center. P.B.F. holds the Thelma Newmeyer Corman Chair in Cancer Research in the VCU Massey Cancer Center.

Conflicts of interest statement. No conflicts of interest are disclosed.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006–2010. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(Suppl 2):ii1–ii56. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(5):492–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefranc F, Brotchi J, Kiss R. Possible future issues in the treatment of glioblastomas: special emphasis on cell migration and the resistance of migrating glioblastoma cells to apoptosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2411–2422. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schickel R, Boyerinas B, Park SM, et al. MicroRNAs: key players in the immune system, differentiation, tumorigenesis and cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27(45):5959–5974. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CZ. MicroRNAs as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1768–1771. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmerman AL, Wu S. MicroRNAs, cancer and cancer stem cells. Cancer Lett. 2011;300(1):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma X, Yoshimoto K, Guan Y, et al. Associations between microRNA expression and mesenchymal marker gene expression in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(9):1153–1162. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malzkorn B, Wolter M, Liesenberg F, et al. Identification and functional characterization of microRNAs involved in the malignant progression of gliomas. Brain Pathol. 2010;20(3):539–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moller HG, Rasmussen AP, Andersen HH, et al. A systematic review of microRNA in glioblastoma multiforme: micro-modulators in the mesenchymal mode of migration and invasion. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;47(1):131–144. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8349-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li CL, Yang WZ, Chen YP, et al. Structural and functional insights into human Tudor-SN, a key component linking RNA interference and editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(11):3579–3589. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tong X, Drapkin R, Yalamanchili R, et al. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 acidic domain forms a complex with a novel cellular coactivator that can interact with TFIIE. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(9):4735–4744. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J, Aittomaki S, Pesu M, et al. Identification of p100 as a coactivator for STAT6 that bridges STAT6 with RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2002;21(18):4950–4958. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J, Valineva T, Hong J, et al. Transcriptional co-activator protein p100 interacts with snRNP proteins and facilitates the assembly of the spliceosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(13):4485–4494. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoo BK, Santhekadur PK, Gredler R, et al. Increased RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) activity contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;53(5):1538–1548. doi: 10.1002/hep.24216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caudy AA, Ketting RF, Hammond SM, et al. A micrococcal nuclease homologue in RNAi effector complexes. Nature. 2003;425(6956):411–414. doi: 10.1038/nature01956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho J, Kong JW, Choong LY, et al. Novel breast cancer metastasis-associated proteins. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(2):583–594. doi: 10.1021/pr8007368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuchiya N, Ochiai M, Nakashima K, et al. SND1, a component of RNA-induced silencing complex, is up-regulated in human colon cancers and implicated in early stage colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67(19):9568–9576. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuruma H, Kamata Y, Takahashi H, et al. Staphylococcal nuclease domain-containing protein 1 as a potential tissue marker for prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(6):2044–2050. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santhekadur PK, Das SK, Gredler R, et al. Multifunction protein staphylococcal nuclease domain containing 1 (SND1) promotes tumor angiogenesis in human hepatocellular carcinoma through novel pathway that involves nuclear factor kappaB and miR-221. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(17):13952–13958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.321646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emdad L, Sarkar D, Lee SG, et al. Astrocyte elevated gene-1: a novel target for human glioma therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(1):79–88. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emdad L, Lee SG, Su ZZ, et al. Astrocyte elevated gene-1 (AEG-1) functions as an oncogene and regulates angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(50):21300–21305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910936106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kegelman TP, Das SK, Hu B, et al. MDA-9/syntenin is a key regulator of glioma pathogenesis. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(1):50–61. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Alizadeh D, Van Handel M, et al. Stat3 inhibition activates tumor macrophages and abrogates glioma growth in mice. Glia. 2009;57(13):1458–1467. doi: 10.1002/glia.20863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy DE, Lee CK. What does Stat3 do? J Clin Invest. 2002;109(9):1143–1148. doi: 10.1172/JCI15650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michaud-Levesque J, Bousquet-Gagnon N, Beliveau R. Quercetin abrogates IL-6/STAT3 signaling and inhibits glioblastoma cell line growth and migration. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318(8):925–935. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li R, Li G, Deng L, et al. IL-6 augments the invasiveness of U87MG human glioblastoma multiforme cells via up-regulation of MMP-2 and fascin-1. Oncol Rep. 2010;23(6):1553–1559. doi: 10.3892/or_00000795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foley NH, Bray IM, Tivnan A, et al. MicroRNA-184 inhibits neuroblastoma cell survival through targeting the serine/threonine kinase AKT2. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:83. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozaki K, Imoto I, Mogi S, et al. Exploration of tumor-suppressive microRNAs silenced by DNA hypermethylation in oral cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(7):2094–2105. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang L, Volinia S, Bonome T, et al. Genomic and epigenetic alterations deregulate microRNA expression in human epithelial ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(19):7004–7009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801615105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin SL, Chiang A, Chang D, et al. Loss of mir-146a function in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. RNA. 2008;14(3):417–424. doi: 10.1261/rna.874808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong TS, Liu XB, Wong BY, et al. Mature miR-184 as Potential Oncogenic microRNA of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Tongue. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(9):2588–2592. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu J, Ryan DG, Getsios S, et al. MicroRNA-184 antagonizes microRNA-205 to maintain SHIP2 levels in epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sciences USA. 2008;105(49):19300–19305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803992105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu C, Teng ZQ, Santistevan NJ, et al. Epigenetic regulation of miR-184 by MBD1 governs neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(5):433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cappellari M, Bielli P, Paronetto MP, et al. The transcriptional co-activator SND1 is a novel regulator of alternative splicing in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2014;33(29):3794–3802. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuchiya N, Nakagama H. MicroRNA, SND1, and alterations in translational regulation in colon carcinogenesis. Mut Res. 2010;693(1–2):94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohsaka S, Wang L, Yachi K, et al. STAT3 inhibition overcomes temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma by downregulating MGMT expression. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11(6):1289–1299. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Yang Z, Ma A, et al. Growth arrest and DNA damage 45G down-regulation contributes to Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation and cellular senescence evasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;59(1):178–189. doi: 10.1002/hep.26628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blanco MA, Aleckovic M, Hua Y, et al. Identification of staphylococcal nuclease domain-containing 1 (SND1) as a Metadherin-interacting protein with metastasis-promoting functions. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(22):19982–19992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.240077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang N, Du X, Zang L, et al. Prognostic impact of Metadherin-SND1 interaction in colon cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(12):10497–10504. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1933-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee SG, Kim K, Kegelman TP, et al. Oncogene AEG-1 promotes glioma-induced neurodegeneration by increasing glutamate excitotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2011;71(20):6514–6523. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.