Abstract

Purpose

A novel technique for highly sensitive detection of multi-resonant fluorine imaging agents was designed and tested with the use of dual-frequency 19F/1H ultra-short echo times (UTE) sampled with a balanced steady-state free precession (SSFP) pulse sequence and 3D radial readout.

Methods

Feasibility of 3D radial balanced UTE-SSFP imaging was demonstrated for a phantom comprising liquid perfluorooctyl bromide (PFOB). Sensitivity of the pulse sequence was measured and compared to other sequences imaging the PFOB (CF2)6 line group including UTE radial gradient-echo (GRE) at α=30°, as well as Cartesian GRE, balanced SSFP, and fast spin-echo (FSE). The PFOB CF3 peak was also sampled with FSE.

Results

The proposed balanced UTE-SSFP technique exhibited a relative detection sensitivity of 51 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2 (α=30°), at least twice that of other sequence types with either 3D radial (UTE GRE: 20 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2) or Cartesian k-space filling (GRE: 12 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2; FSE: 16 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2 balanced SSFP: 23 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2 In vivo imaging of angiogenesis-targeted PFOB nanoparticles was demonstrated in a rabbit model of cancer on a clinical 3T scanner.

Conclusion

A new dual 19F/1H balanced UTE-SSFP sequence manifests high SNR, with detection sensitivity more than twofold better than traditional techniques, and alleviates imaging problems caused by dephasing in complex spectra.

Keywords: 19F MRI, molecular imaging, ultra short echo time, balanced steady state free precession

INTRODUCTION

Magnetic resonance methods are emerging for functional and quantitative physiological detection of nuclei other than hydrogen (1), all of which require specific optimization of imaging techniques and hardware. Concomitant development of novel contrast agents has created possibilities for imaging a variety of nuclei, for example recently the multiple molecular species of liquid perfluorocarbons in nanoparticle formulations (2,3). Targeted perfluorocarbon (PFC) imaging agents profess the opportunity to target and quantify markers of disease in cardiovascular, oncological, and other applications. Some of the early work involved targeted cells, both in vitro and in vivo, and tracking the cells by detecting their unique fluorine signatures (4,5). Other techniques involve the accumulation of tracers by macrophages, which can then be imaged by their fluorine signals (6). Still other agents have been shown to target pathological tissues to detect and quantify biomarker concentration, as exemplified by ανβ3-integrin targeting of angiogenesis in cancer and atherosclerosis (7-10). Moreover, commercial interest in such agents by pharmaceutical companies has been demonstrated by recent reports of angiogenesis targeting and imaging with 19F compounds (11).

19F magnetic resonance spectroscopy and imaging offer several advantages over hydrogen-based methods, including highly specific detection due to an absence of biological background signal, and the ability to quantify local concentration of fluorinated agents (12). As such, 19F MRI bears a high potential for molecular imaging allowing the direct quantification of targeted PFC nanoparticle (NP) emulsions (13). Previous in vivo reports of PFC NP have exploited the single resonance peak of perfluoro-15-crown-5-ether (PFCE; C10F20O5) (14). However, perfluorooctyl bromide (PFOB; CF3-(CF2)6-CF2Br) is a more clinically-relevant NP core with a better understood human safety profile (15), but it exhibits a more complex spectrum with seven 19F resonance peaks and multiple relaxation conditions (16).

Fluorine-based detection incurs several inherent technical challenges. Many agents have short apparent T2’ relaxation times, which can vary across their spectral peaks (17). In addition, rich spectra and large chemical shifts (CS) like those found in PFOB add significant complexity that challenges optimal signal detection. Several methods have been developed to manage CS artifacts and cope with short apparent T2’ times encountered in multinuclear MR. Mastropietro et al. have recently optimized the sequence parameters of fast spin-echo (FSE/RARE) for some 19F reporters, but different fluorinated agents will likely require individual parameter tuning based on their spectral properties and the local environment (18). Single 19F resonances, such as the CF3 line group in PFOB, have been utilized (19), but significant tradeoffs in SNR efficiency remain when other lines are ignored. Others have investigated chemical species separation using an iterative decomposition with echo asymmetry and least-squares estimation (IDEAL), which requires a complex δB0 correction (20,21). In an effort to capture signal from all PFOB spins, echo-time encoding with relaxation correction has been implemented (22), in addition to pulse-phase encoding (PPE) (23). Lastly, chemical shift independent techniques like fluorine ultrafast turbo spectroscopic imaging (F-uTSI) have been employed to register the entire 19F spectrum (24), albeit with a significant acquisition time penalty.

Perhaps the most straightforward method to image complex 19F spin systems in consideration of destructive phase interference is to acquire the signal before the spins dephase, as in ultra-short echo time (UTE) imaging (25). Line dephasing occurs over time, when the spin species of an imaging agent are subject to individual Larmor precession according to their respective chemical shift, which can lead to destructive signal overlay. In addition, transverse relaxation prevents a full signal recovery at later time points. Short echo time sequences like UTE offer the ability to capture these spins before line dephasing occurs, and thus retain their NMR signal to potentially boost the SNR (26). Balanced steady-state free precession (SSFP) is a technique in which each gradient pulse within one TR is compensated by a gradient pulse with an opposite polarity, resulting in a single, rephased magnetization vector (27). As such, the SSFP sequence retains much of the initial magnetization (M0), which yields a steady state MR signal with high achievable SNR. Accordingly, we devised a new technique—dual-frequency 19F/1H UTE with a balanced SSFP pulse sequence and 3D radial readout—to permit highly sensitive detection of multi-resonant imaging labels like PFOB.

METHODS

Pulse Sequence Design

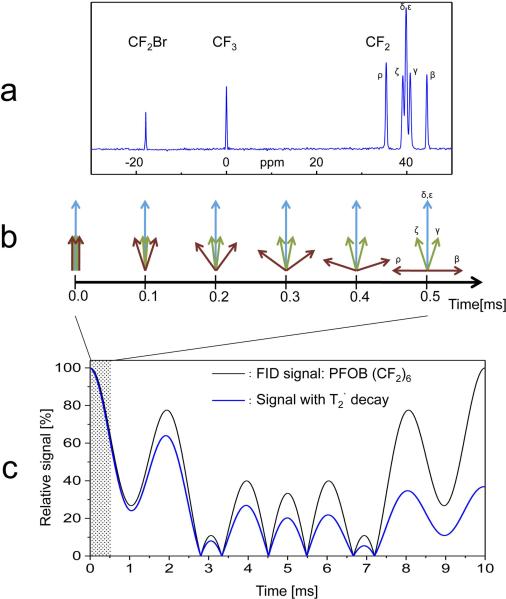

In order to optimize pulse sequence parameters, the spectral characteristics and NMR relaxation properties of the PFOB molecule were analyzed (Fig. 1a). In addition to single 19F resonance peaks for the PFOB CF2Br and CF3 groups, the CF2 line group contains twelve of the seventeen fluorine nuclei, which result in five spectral components (at 3T: 0, ± 100 Hz, ± 500 Hz). As shown in Figure 1b, the five proximate chemical shift (CS) components of the CF2 group, represented by different spin vectors (β, γ, δ, ε, ζ, ρ), lead to destructive signal overlay at larger echo times (e.g., 2.8 ms). However, all CS components remain within a phase range of ± 90° for 0.5 ms and are not yet significantly affected by the apparent T2’ relaxation (10 ms) (17,28). Using a UTE-SSFP sequence with an echo time of 100 μs, a typical gradient performance of 200 Tm−1s−1 and a pixel bandwidth of 1 kHz, the FID readout requires ~0.6 ms resulting in a spatial resolution of ~1 mm, which is well suited for the detection and quantification of targeted PFOB-NP. During a fast FID readout, as in the balanced UTE-SSFP technique presented here, the relative signal from the CF2 resonances remains above 60%, which cannot be recovered at later echo times.

FIG. 1.

a: Perfluorooctyl bromide (PFOB: CF3-(CF2)6-CF2Br)19F spectrum. b: All chemical shift components of PFOB CF2 line group (β, γ, δ, ε, ζ, ρ) remain within a phase range of ± 90° for 0.5 ms. c: 19F signal evolution of the (CF2)6 line group with and without apparent T2’ relaxation. During a fast FID readout as in the balanced UTE-SSFP technique (shaded region), the relative signal remains above 60%, which cannot be recovered for later echo times.

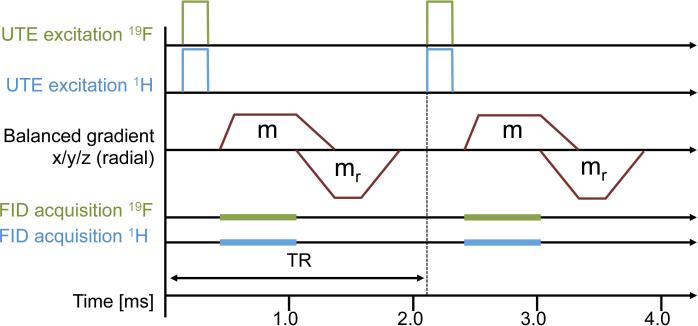

A simultaneous 3D 19F/1H balanced UTE-SSFP pulse sequence was designed to capture these CF2 resonances (Fig. 2). The sequence consists of simultaneous 19F/1H RF excitation (29) and subsequent FID acquisition at an ultra-short echo time, using balanced gradients with a Wong-type (30) radial readout trajectory. The UTE excitation and FID acquisition are designed to acquire the 19F signal before dephasing develops, while the balanced SSFP gradients are designed to exploit the achievable high steady-state signal. The simultaneous 1H excitation and acquisition is not necessarily part of the sensitive 19F detection sequence but is beneficial for an efficient scan time and precise co-localization of fluorine signals with the underlying anatomy.

FIG. 2.

A simultaneous 3D 19F/1H balanced UTE-SSFP pulse sequence, consisting of simultaneous 19F/1H RF excitation and subsequent FID acquisition at an ultra-short echo time, using balanced gradients with a Wong-type (30) radial readout trajectory. Logical gradient lobes (m, mr) are superimposed into a single continuous gradient waveform when executed on the physical gradient coils.

Phantom Imaging Experiments

The study was performed on a 3T clinical whole-body scanner (Achieva, Philips Healthcare, The Netherlands), outfitted with a dual 19F/1H spectrometer system (29). Dual-resonant 19F/1H RF coils were used, which can either transmit or receive at both frequencies simultaneously (31). As these coil types have identical B1 field properties at the 1H and 19F frequencies, the standard RF power adjustment for flip angle calibration, performed on 1H, can be used for 19F without modification.

Feasibility of balanced UTE-SSFP imaging was demonstrated in a phantom experiment using a bottle containing a flask (inner diameter 38 mm) filled with perfluorooctyl bromide (CF3-(CF2)6-CF2 r) surrounded by water. The simultaneous 19F/1H 3D balanced UTE-SSFP sequence with Wong-type radial readout was implemented using a 19F/1H dual-tuned transmit/receive small-animal solenoid coil (inner diameter 7 cm) with the following parameters: FOV = 128 mm, matrix 1283, isotropic voxel Δx = 1.0 mm, α = 30°, excitation bandwidth exBW = 5 kHz centered on the PFOB-CF2 line group, pixel bandwidth pBW = 900 Hz, TR = 2.1 ms, TE = 90 μs (FID sampling), Texp = 71 s.

The effect of the balanced gradient scheme on sequence performance was determined by acquiring an additional 3D radial UTE gradient-echo (GRE) data set using identical acquisition parameters (α = 30°), but without balanced gradients (TR = 3.6 ms). Additionally, a 3D radial UTE GRE sequence at Ernst angle (αE = 5°) was tested, following determination of the T1 relaxation time for the PFOB-CF2 line group (840 ms) (32). The GRE sequences do not apply RF spoiling, such that the signal may be optimized at α > αE, depending on the actual T2 relaxation time. Slab-selective (10 mm) serial spectroscopic acquisitions were employed on both the CF2 and CF3 line groups of the PFOB phantom to determine T1 using inversion recovery, FID sampling, and variable TI delay (10-2810 ms in 200 ms steps), as well as apparent T2’ using spin-echo TE delay (13-53 ms in 2 ms steps for CF2 and 13-583 ms in 30 ms steps for CF3).

For comparison to existing techniques, 3D GRE, balanced SSFP, and fast spin-echo (FSE) sequences with Cartesian k-space sampling were used with identical FOV (128 mm) and spatial resolution (1×1×1 mm3 voxels). An elliptical restriction of the two phase encoding dimensions was applied to the 3D Cartesian sampling such that the actually sampled portion of k-space was similar to the radial sampling in the UTE and balanced UTE-SSFP sequences. Other gradient-echo imaging parameters included α = 30°, exBW = 5 kHz, pBW = 900 Hz, TR/TE = 4.8/2.1 ms, Texp = 104 s. Balanced SSFP was used with α = 30°, exBW = 5 kHz, pBW = 900 Hz, TR/TE = 4.2/2.1 ms, Texp = 89 s. Fast spin-echo parameters included α = 90°, FSE acceleration factor 116, pBW = 660 Hz, exBW = 2830 Hz, TR/TE = 4000/7.4 ms, Texp = 1032 s. For further comparison to alternative line selection methods (19), a fast spin-echo sequence was performed on the CF3 line using the same FSE parameters.

Sensitivity Comparisons

In the phantom imaging experiments, sensitivity was selected as a metric to compare imaging techniques in order to take into account SNR as well as scan time for each sequence. Detection sensitivity (S) was defined and calculated as:

| [1] |

where SNR is the achieved signal-to-noise ratio, Texp is the duration of the sequence, and (mol/voxel) is the amount of PFOB agent within an imaging voxel. In order to assess the signal-to-noise ratio, 19F signal I0 was measured on the magnitude image in a rectangular region of interest (ROI) within the PFOB phantom. Noise was determined from the standard deviations σ[Re] and σ[Im] in a rectangular ROI at the border of real and imaginary images. An area separated from the phantom and free of coherent background signal in any sequence type (e.g., by signal blurring) was chosen. From this data, SNR was calculated as:

| [2] |

In Vivo Imaging Experiment

For in vivo validation, targeted PFOB NPs were imaged in a rabbit model of cancer. All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Studies Committee of Washington University in St. Louis. Male New Zealand White rabbits (~2 kg, n = 4) were implanted in the popliteal fossa of the left hind leg with 2-3 mm VX2 adenocarcinoma tumors (National Cancer Institute, MD), which grew to ~15 mm within 2 weeks (33). Imaging was performed 3h post-injection of 1.0 ml/kg ανβ3-integrin targeted NP with PFOB core as previously described (34). To avoid signal contamination from inhaled fluorinated anesthesia, a xylazine (10mg/kg) / ketamine (85 mg/kg) i.m. injection was used for anesthesia induction, which was maintained with a ketamine i.v. infusion (18 mg/kg/hr). The radial 3D balanced UTE-SSFP sequence was implemented using a 19F/1H dual-tuned transmit/receive surface coil (7×12 cm) with the following parameters: FOV = 140 mm, matrix 643, isotropic voxel Δx = 2.19 mm, α = 30°, exBW = 5 kHz centered on the PFOB-CF2 line group, pBW = 900 Hz, TR = 1.75 ms, TE = 90 μs (FID sampling), and a scanning time of 30 minutes.

For the in vivo experiment, the radial k-space data were reconstructed at full resolution for the 1H component and a lower resolution with higher signal-to-noise for the 19F component. The latter was achieved by applying a flat k-space weighting to the data outside a radius corresponding to 20% of the fully sampled sphere in k-space (20% of the Nyquist radius) and using the usual quadratic weighting for the center of k-space (35). Since most signal intensity is located close to the center of k-space, flat weighting of higher k-values does not lead to signal losses but reduces noise amplification in high k-values and thus further improves SNR at the expense of spatial resolution.

RESULTS

The balanced UTE-SSFP pulse sequence was successfully implemented and run on a 3T whole-body scanner. Table 1 summarizes the observed sensitivity for the investigated sequence types, as calculated by Eq. 1. With S = 51 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2, the proposed balanced UTE-SSFP technique demonstrates a sensitivity of at least twice that of other sequence types. An example phantom image using this technique is shown in Figure 3d, together with the ROIs used for signal-to-noise measurements. 3D UTE GRE sequences without balanced gradients at α = 30° and α = 5° (Ernst angle) exhibit substantially lower sensitivities (20 and 8 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2, respectively). Analysis of the spectroscopic series data revealed a T1 of 840±40 ms and 1000±40 ms for the CF2 and CF3 peaks, respectively, and an apparent T2’ of 10±1 ms and 230±10 ms for the CF2 and CF3 peaks, respectively.

Table 1.

Sensitivity of 19F MR Acquisition Techniques

| PFOB Line(s) | 19F Sequence | Sensitivity (μmolPFOB−1min−1/2)a |

|---|---|---|

| CF3 | Cartesian fast spin-echo | 7 |

| (CF2)6 | Cartesian gradient-echo (α=30°) | 12 |

| Cartesian fast spin-echo | 16 | |

| Cartesian balanced SSFP (α=30°) | 23 | |

| Radial UTE gradient-echo (α=5°) | 8 | |

| Radial UTE gradient-echo (α=30°) | 20 | |

| Radial balanced UTE-SSFP (α=30°) | 51 | |

Sensitivity measured as S = SNR×(mol/voxel)−1×Texp−1/2, where SNR is the achieved signal-to-noise ratio, Texp the sequence duration, and (mol/voxel) the amount of PFOB agent within an imaging voxel.

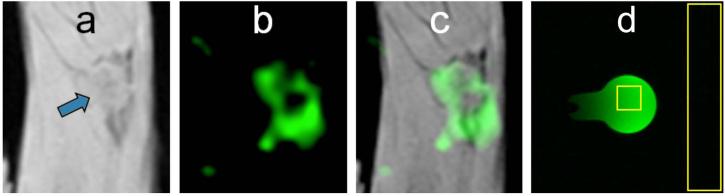

FIG. 3.

Molecular imaging of ανβ3-integrin targeted NP on VX2 tumor in rabbits by 19F MRI. a: 1H image shows tumor location (arrow) in rabbit popliteal fossa. b: NP with a perfluorooctyl bromide (PFOB) core were imaged with a novel balanced UTE-SSFP based 3D radial sequence. c: Image overlay demonstrates the anatomical co-localization. d: 19F balanced UTE-SSFP image of the phantom consisting of PFOB in a flask surrounded by water (signal and noise ROIs shown for SNR calculation).

The second-best sequence is balanced SSFP with a Cartesian k-space trajectory (23 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2, demonstrating the value of using balanced gradients for the detection of perfluorocarbons. For the CF2 group, the proximate CS components lead to destructive signal overlay at larger echo times (e.g., 2.8 ms), which are difficult to separate with line selection techniques. The 3D gradient-echo acquisition demonstrates this signal loss (TE = 2.1 ms), with a measured sensitivity of 12 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2. Fast spin-echo techniques are typically highly SNR efficient, but are not optimal for perfluorocarbons like PFOB (16 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2, since the achievable echo times (here TE = 7.4 ms) do not allow full signal combination of the CF2 group. Selecting the CF3 group is possible, but this choice only uses 3 of the 17 available fluorine nuclei, which resulted in lowered sensitivity (7 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2.

In vivo imaging of angiogenesis-targeted PFOB nanoparticles was successful in a rabbit model of cancer, demonstrating heterogeneous areas of neovasculature at the tumor rim (Fig. 3a, arrow) as expected in this established VX2 tumor model. The fluorinated core of this PFOB NP emulsion was imaged with the simultaneous 19F/1H balanced UTE-SSFP sequence using parameters that were tested in the phantom experiment. The resultant 19F signal clearly elucidates the heterogeneous distribution of detected NP (Fig. 3b), which is overlaid on 1H anatomy to demonstrate anatomical co-localization (Fig. 3c).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study introduced and tested a novel pulse sequence, 19F/1H balanced UTE-SSFP with 3D radial readout, for the imaging of non-proton nuclei with complex spectra. The sequence was implemented on a clinical 3T scanner to enable detection of multi-resonant fluorine imaging labels like PFOB with high sensitivity as compared to traditional techniques. A majority of the PFOB fluorine nuclei (12 of 17) are located in the CF2 resonances, which are distributed over a wide chemical shift range. Within the 90 μs echo time of the balanced UTE-SSFP sequence however, we showed that dephasing does not lead to destructive superposition of these resonances, which serves to maximize the obtained signal. The signal gain by constructive addition of all CF2 lines over-compensates the loss in SNR-efficiency imposed by 3D radial sampling (25%) and the FID readout, which requires twice the number of k-space lines, since all start at kx,y,z = 0 (36). Point-spread function effects of the k-space sampling might change the actually sampled voxel volume and thus influence the sensitivity comparison. Because of the chosen elliptical restriction of the phase encoding in Cartesian sampling, these effects were considered to be negligible.

The sensitivity obtained for the gradient-echo sequence using radial UTE readout allows separating the contributions of short echo times (reduced dephasing) and the use of balanced gradients. Without the spoiler gradients used in GRE, TR is decreased for the balanced case, which accounts for about 30% of the observed sensitivity gain (20 to 51 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2. Thus, the application of balanced gradients can be estimated to result in a twofold sensitivity gain for the CF2 line group. This result is similar to the sensitivity gain found by introducing balanced gradients in the Cartesian CF2 acquisitions (12 to 23 μmolPFOB−1min−1/2).

The results show a substantial, 2.5-fold increase in the UTE GRE signal from Ernst angle (αE = 5° for T1 = 840 ms) to α = 30°. According to GRE signal theory without RF spoiling (see e.g. (37), Eq. 4.22, TR = 4.8 ms, T1 = 840 ms) this is only expected for species with actual T2 values much larger than the measured apparent T2’ of 10 ms (consistent with (17)). At an estimated actual T2 of 110 ms, the GRE signal theory predicts a 2.5-fold signal increase when changing from α = 5° to 30°, while the signal gain would be lower at any significantly shorter T2. The apparent T2’, as measured by multiple spin echo times, is known to be strongly influenced and shortened by homonuclear J-coupling (17). Recent work by Jacoby et al. (16) demonstrates this point, measuring the T2 of emulsified PFOB, which varies over the CF2 peaks from 75 to 80 ms. Additionally, Giraudeau et al. (19) have shown exceptionally high actual T2 values of 400 to 900 ms for the PFOB CF3 group when using narrow band refocussing in spin-echo to reduce J-coupling effects. Interestingly, the T2 is shown to increase at shorter echo time, which is hypothesized to be due to a reduced influence of the coupled (quantum) state on relaxation at shorter TE. Furthermore, the actual T2, and hence signal, depends on whether the PFOB is neat, encapsulated, or bound to a target (16,19). Our results suggest that an actual T2 value (and not apparent T2’) is required to correctly model the signal gain obtained by flip angle optimization and by applying balanced gradients.

The flip angle choice of α = 30° in the present study was suggested by a previous study using a Cartesian GRE sequence on fibrin target bound PFOB nanoparticles (38), which showed a signal optimum at α = 30° to 35° and a signal decay for larger flip angles. While a sequence comparison at a fixed flip angle, as performed in this study, is clearly demonstrating the respective signal gain by using ultra short echo time and balanced gradients, the individual optimum flip angle for each sequence type was not explored. Inserting the estimated actual T2 of 110 ms (neat PFOB) into the signal theory for balanced SSFP (see e.g. (37), Eq. 4.24) allows one to estimate an optimum flip angle and to predict the signal gain by introducing balanced gradients as compared to GRE. According to this theory, balanced gradients at α = 30° would result in a 50% signal increase and the signal maximum would be expected at 40°. The actually observed signal gain (twofold) does not match this calculation, likely due to the fact that the actual T2 is not well known and may depend on sequence parameters. A more detailed analysis of the actual T2 relaxation of the PFOB CF2 line group for neat and encapsulated PFOB forms is beyond the scope of this work but would provide important information to optimize balanced UTE-SSFP sequences (e.g. flip angle choice). A flip angle of 30° could be a practical choice for in vivo applications of the proposed balanced UTE-SSFP technique for PFOB loaded nanoparticles, where T2 relaxation may be faster due to restricted motion. The current parameter choice in balanced UTE-SSFP led to the successful observation of ανβ3-integrin targeted NP with a PFOB core, as shown in the VX2 tumor model.

Although the focus of this work was on PFOB nanoparticle emulsions, the balanced UTE-SSFP technique offers several benefits for multinuclear imaging of many non-proton agents, such as perfluorodecalin (C10F18) or perfluorooctane (C8F18) (16,39). This pulse sequence is optimal for contrast agents with a short apparent T2’ relaxation, due to the ultra-short echo time and fast FID acquisition. Agents bound to molecular targets may be of particular interest, since they exhibit reduced T2 relaxation due to decreased molecular motion (38). In addition, the balanced SSFP approach yields high SNR, in particular for imaging labels with characteristically unfavorable long T1 relaxation for gradient-echo methods due to M0 saturation, as is the case with PFOB. The combination of these two schemes offers a flexible pulse sequence for complex resonant structures, which can be customized to the agent of choice by altering offset frequency and excitation bandwidth to dial in a particular line group.

As shown in this study, the proposed balanced UTE-SSFP sequence can be combined with simultaneous dual-nuclei techniques. The simultaneously acquired proton signal could be used for efficient anatomical localization and quantitative calibration of the non-proton signal via sensitivity assessment of the dual-tuned RF coil. Once the complex spectral signal is acquired with this sequence, the 3D radially-filled k-space data can be directly reconstructed, and does not require post-processing as would chemical shift imaging. As an added benefit, the 3D radial data set offers the potential for multi-resolution reconstruction, allowing analysis of the 19F and 1H data at different spatial resolution (35). Note that the reconstruction of the 19F data at a lower resolution and higher SNR was only performed for the in vivo experiment to demonstrate this capability in sparse molecular imaging environments; all 19F data were reconstructed at full resolution in the phantom experiments when comparing balanced UTE-SSFP to existing techniques, as seen in Figure 3d. Finally, this unique simultaneously acquired data provides an opportunity for motion correction of the non-proton signal with temporal sub-sampling of the 1H data (29). Although a prototype dual 19F/1H spectrometer system was used for simultaneous acquisition in this study, a similar 19F UTE-SSFP sequence was also successfully implemented on a standard multinuclear scanner platform.

In this study, the balanced UTE-SSFP sequence was shown to be more sensitive than traditional acquisition techniques in the context of multinuclear imaging of contrast agents with complex spectra. However, some agents may not require advanced line combination, such as those with single resonance peaks. Application of the balanced UTE-SSFP sequence for such agents might result in decreased SNR-efficiency due to the 3D radial sampling and FID readout. In addition, the bandwidth of this technique may not be large enough to cover all lines of an agent, because of the large chemical shifts found in 19F. Thus, a particular line group must be selected within a bandwidth of approximately 1-2 kHz, for an appropriate spatial resolution of the 3D radial readout with standard gradient systems. While advantageous for the detection of PFOB where a majority of 19F spins are found in the CF2 line group covering ~1 kHz, this bandwidth restriction may be a limitation for other chemical species. Another obstacle for this sequence was found in the classic balanced SSFP banding artifacts that were observed in both the 1H and 19F components in some images, but these were reduced by shortening TR and can be moved out of the region of interest by adjusting the offset frequency for the balanced signal.

In conclusion, radial 3D balanced UTE-SSFP is a robust pulse sequence that yields high SNR, with detection sensitivity more than twofold improved over more traditional techniques, while also alleviating problems associated with extended longitudinal relaxation times, short apparent T2’, and complex spectral properties of imaging agents. This technique was demonstrated for dual-frequency 19F/1H MRI on a clinical scanner that allows highly sensitive in vivo detection of multi-resonant imaging labels like perfluorooctyl bromide. The synergistic combination of an optimized imaging technique and a biocompatible contrast agent should facilitate translation into clinical use.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Todd A. Williams and John S. Allen for their help performing the animal experiments, and Angana Senpan for her help preparing the PFC NP emulsion.

Grant sponsors: NIH; Grant number: R01 HL073646 (SAW). NIH/DOD; Grant numbers: HL112518 (GML), HL113392 (GML/EMW), CA100623 (GML), CA154737 (GML), AR056468 (GML), CA136398 (GML), and NS073457 (GML). AHA predoctoral fellowship; Grant number: 11PRE7530046 (MJG). Barnes-Jewish Hospital Charitable Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wijnen JP, van der Kemp WJ, Luttje MP, Korteweg MA, Luijten PR, Klomp DW. Quantitative 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the human breast at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68(2):339–348. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winter PM, Cai K, Caruthers SD, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Emerging nanomedicine opportunities with perfluorocarbon nanoparticles. Expert Rev Med Devic. 2007;4(2):137–145. doi: 10.1586/17434440.4.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan X, River JN, Muresan AS, Popescu C, Zamora M, Culp RM, Karczmar GS. MRI of perfluorocarbon emulsion kinetics in rodent mammary tumours. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51(2):211–220. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/2/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahrens ET, Flores R, Xu HY, Morel PA. In vivo imaging platform for tracking immunotherapeutic cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(8):983–987. doi: 10.1038/nbt1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crowder KC, Hughes MS, Marsh JN, Barbieri AM, Fuhrhop RW, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Sonic activation of molecularly-targeted nanoparticles accelerates transmembrane lipid delivery to cancer cells through contact-mediated mechanisms: Implications for enhanced local drug delivery. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31(12):1693–1700. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahrens ET, Zhong J. In vivo MRI cell tracking using perfluorocarbon probes and fluorine-19 detection. NMR Biomed. 2013;26(7):860–871. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6(4):389–395. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morawski AM, Lanza GA, Wickline SA. Targeted contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound. Curr Opin Biotech. 2005;16(1 SPEC. ISS.):89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winter PM, Caruthers SD, Allen JS, Cai K, Williams TA, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Molecular imaging of angiogenic therapy in peripheral vascular disease with αvβ3-integrin-targeted nanoparticles. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(2):369–376. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmieder AH, Caruthers SD, Zhang H, Williams TA, Robertson JD, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Three-dimensional MR mapping of angiogenesis with α5β1(ανβ3)-targeted theranostic nanoparticles in the MDA-MB-435 xenograft mouse model. FASEB J. 2008;22(12):4179–4189. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-112060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giraudeau C, Geffroy F, Meriaux S, Boumezbeur F, Robert P, Port M, Robic C, Le Bihan D, Lethimonnier F, Valette J. 19F molecular MR imaging for detection of brain tumor angiogenesis: in vivo validation using targeted PFOB nanoparticles. Angiogenesis. 2013;16(1):171–179. doi: 10.1007/s10456-012-9310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu JX, Kodibagkar VD, Cui WN, Mason RP. F-19: A versatile reporter for non-invasive physiology and pharmacology using magnetic resonance. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12(7):819–848. doi: 10.2174/0929867053507342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morawski AM, Winter PM, Yu X, Fuhrhop RW, Scott MJ, Hockett F, Robertson JD, Gaffney PJ, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Quantitative “magnetic resonance immunohistochemistry” with ligand-targeted 19F nanoparticles. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(6):1255–1262. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keupp J, Caruthers SD, Rahmer J, Williams TA, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Fluorine-19 MR molecular imaging of angiogenesis on Vx-2 tumors in rabbits using ανβ3-targeted nanoparticles.. Proceedings of the 17th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Honolulu, Hawaii, USA. 2009. p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruiz-Cabello J, Barnett BP, Bottomley PA, Bulte JW. Fluorine (19F) MRS and MRI in biomedicine. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(2):114–129. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacoby C, Temme S, Mayenfels F, Benoit N, Krafft MP, Schubert R, Schrader J, Flogel U. Probing different perfluorocarbons for in vivo inflammation imaging by 19F MRI: image reconstruction, biological half-lives and sensitivity. NMR Biomed. 2014;27(3):261–271. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sotak CH, Hees PS, Huang HN, Hung MH, Krespan CG, Raynolds S. A new perfluorocarbon for use in fluorine-19 magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29(2):188–195. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mastropietro A, De Bernardi E, Breschi GL, Zucca I, Cametti M, Soffientini CD, de Curtis M, Terraneo G, Metrangolo P, Spreafico R, Resnati G, Baselli G. Optimization of rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) pulse sequence parameters for F-19-MRI studies. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40(1):162–170. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giraudeau C, Flament J, Marty B, Boumezbeur F, Meriaux S, Robic C, Port M, Tsapis N, Fattal E, Giacomini E, Lethimonnier F, Le Bihan D, Valette J. A new paradigm for high-sensitivity 19F magnetic resonance imaging of perfluorooctylbromide. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(4):1119–1124. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeder SB, Wen Z, Yu H, Pineda AR, Gold GE, Markl M, Pelc NJ. Multicoil Dixon chemical species separation with an iterative least-squares estimation method. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(1):35–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu H, Shimakawa A, McKenzie CA, Brodsky E, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. Multiecho water-fat separation and simultaneous R2* estimation with multifrequency fat spectrum modeling. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(5):1122–1134. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keupp J, Schaeffter T. Efficient 19F imaging of multi-spectral-line contrast agents: aliasing serves to minimize time encoding.. Proceedings of the 14th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Seattle, Washington, USA. 2006. p. 913. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keupp J, Wickline SA, Lanza GM, Caruthers SD. Hadamard-type pulse-phase encoding for imaging of multi-resonant fluorine-19 nanoparticles in targeted molecular MRI.. Proceedings of the 18th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Stockholm, Sweden. 2010. p. 982. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamerichs R, Yildirim M, Nederveen AJ, Stoker J, Lanza GM, Wickline SA, Caruthers SD. In vivo 3D 19F fast spectroscopic imaging (F-uTSI) of angiogenesis on Vx-2 tumors in rabbits using targeted perfluorocarbon emulsions.. Proceedings of the 18th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Stockholm, Sweden. 2010. p. 457. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahmer J, Bornert P, Groen J, Bos C. Three-dimensional radial ultrashort echo-time imaging with T2 adapted sampling. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55(5):1075–1082. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmid F, Holtke C, Parker D, Faber C. Boosting 19F MRI—SNR efficient detection of paramagnetic contrast agents using ultrafast sequences. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(4):1056–1062. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheffler K, Lehnhardt S. Principles and applications of balanced SSFP techniques. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(11):2409–2418. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-1957-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee HK, Nalcioglu O, Buxton RB. Correction of chemical-shift artifacts in 19F imaging of PFOB: a robust signed magnitude method. Magn Reson Med. 1992;23(2):254–263. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910230206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keupp J, Rahmer J, Grässlin I, Mazurkewitz PC, Schaeffter T, Lanza GM, Wickline SA, Caruthers SD. Simultaneous dual-nuclei imaging for motion corrected detection and quantification of 19F imaging agents. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66(4):1116–1122. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong STS, Roos MS. A strategy for sampling on a sphere applied to 3D selective RF pulse design. Magn Reson Med. 1994;32(6):778–784. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hockett FD, Wallace KD, Schmieder AH, Caruthers SD, Pham CTN, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Simultaneous dual frequency 1H and 19F open coil imaging of arthritic rabbit knee at 3T. IEEE T Med Imaging. 2011;30(1):22–27. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2056689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ernst RR, Anderson WA. Application of Fourier Transform Spectroscopy to Magnetic Resonance. Rev Sci Instrum. 1966;37(1):93–102. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu G, Lijowski M, Zhang H, Partlow KC, Caruthers SD, Kiefer G, Gulyas G, Athey P, Scott MJ, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Imaging of Vx-2 rabbit tumors with αvβ3- integrin-targeted 111In nanoparticles. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(9):1951–1957. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neubauer AM, Caruthers SD, Hockett FD, Cyrus T, Robertson JD, Allen JS, Williams TD, Fuhrhop RW, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Fluorine cardiovascular magnetic resonance angiography in vivo at 1.5 T with perfluorocarbon nanoparticle contrast agents. J Cardiov Magn Reson. 2007;9(3):565–573. doi: 10.1080/10976640600945481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahmer J, Keupp J, Caruthers SD, Lips O, Williams TA, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Dual resolution simultaneous 19F/1H in vivo imaging of targeted nanoparticles.. Proceedings of the 17th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Honolulu, Hawaii, USA. 2009. p. 612. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lauzon ML, Rutt BK. Effects of polar sampling in k-space. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(6):940–949. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vlaardingerbroek MT, Boer JAd. Magnetic resonance imaging : theory and practice. Springer; New York, NY: 2003. p. 499. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keupp J, Schmieder AH, Wickline SA, Lanza GM, Caruthers SD. Target-binding of perfluoro-carbon nanoparticles alters optimal imaging parameters using F-19 molecular MRI: a study using fast in vitro screening and in vivo tumor models.. Proceedings of the 18th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Stockholm, Sweden. 2010. p. 1929. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srinivas M, Cruz LJ, Bonetto F, Heerschap A, Figdor CG, de Vries IJ. Customizable, multi-functional fluorocarbon nanoparticles for quantitative in vivo imaging using 19F MRI and optical imaging. Biomaterials. 2010;31(27):7070–7077. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]