Abstract

Background

Children with neurologic or neurodevelopmental disorders (NNDDs) are at increased risk of complications from influenza. Although the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recognized NNDDs as high-risk conditions for influenza complications since 2005, little is known about influenza vaccination practices in this population.

Methods

CDC collaborated with Family Voices, a national advocacy group for children with special healthcare needs, to recruit parents of children with chronic medical conditions. Parents were surveyed about their knowledge, attitudes, and practices surrounding influenza vaccination. The primary outcome of interest was parental report of vaccination, or intent to vaccinate, at the time of survey participation. CDC also collaborated with the American Academy of Pediatrics to recruit primary care and specialty physicians who provide care for high-risk children, specifically those with neurologic conditions. The primary outcome was physician recognition of ACIP high-risk influenza conditions.

Results

2138 surveys were completed by parents of children with high-risk conditions, including 1143 with at least one NNDD. Overall, 50% of children with an NNDD were vaccinated, or their parents planned to have them vaccinated against influenza. Among all 2138 children, in multivariable analysis, the presence of a respiratory condition and prior seasonal influenza vaccination was significantly associated with receipt or planned current season influenza vaccination, but the presence of an NNDD was not. 412 pediatricians completed the provider survey. Cerebral palsy was recognized as a high-risk influenza condition by 74% of physician respondents, but epilepsy (51%) and intellectual disability (46%) were less commonly identified.

Conclusions

Our estimates of influenza vaccination in children with NNDDs are comparable to published reports of vaccination in healthy children, which continue to be suboptimal. Education of parents of children with NNDDs and healthcare providers about influenza and the benefit of annual influenza vaccination is needed.

Keywords: Influenza, Immunization, Neurologic, High-risk, Disability

1. Introduction

Seasonal influenza epidemics are associated with an estimated average of more than 200,000 hospitalizations and 3400–49,000 deaths among all age groups in the U.S. annually [1,2] The burden of disease is especially high among young children and those with certain chronic medical conditions. Since 2005, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has included cognitive dysfunction, spinal cord injuries, seizure disorders, and other neuromuscular disorders as high-risk conditions for complications associated with influenza [3]. Such neurologic and neurodevelopmental conditions are associated with higher rates of influenza-associated respiratory failure and death [4,5]. One-third of reported pediatric influenza-associated deaths among children with documented medical histories between 2004 and 2012 in the U.S. occurred in children with neurologic disorders [6]. This was even more evident during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic; of 343 pediatric deaths associated with laboratory-confirmed 2009 H1N1 virus infection in the U.S., 146 (43%) had at least one known underlying neurologic or neurodevelopmental disorder (NNDD) [7]. Among these 146 children, neurodevelopmental disorders – specifically intellectual disability (111, 76%) and cerebral palsy (51, 35%) – and epilepsy (74, 51%) predominated.

While several studies have focused on influenza vaccination practices among high-risk children and their healthcare providers, most have focused on children with asthma and have not included those with NNDDs [8–11]. To better understand influenza vaccination practices among these children, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted surveys of parents of children with NNDDs and healthcare providers who care for children with NNDDs. To our knowledge, this is the first study of influenza vaccination among children with NNDDs.

2. Methods

2.1. Parent survey

CDC collaborated with Family Voices (FV) (www.familyvoices.org), a national advocacy group for children with special healthcare needs, to recruit parents of children with chronic medical conditions. An on-line survey was distributed to members of the FV listservs and administered from September 6 to October 24, 2011 in both English and Spanish. Surveys were disseminated by individual FV chapters in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Parents or other caregivers were queried about their knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to having their children vaccinated with seasonal influenza vaccine. The primary outcome of interest was vaccination at the time of survey participation, or intent to vaccinate during the 2011–2012 influenza season. Specifically, parents were asked “Have you had your child vaccinated against the seasonal flu in the current flu season?” Parents who responded “no” were asked to provide a reason. Responses that noted vaccination had been scheduled but not yet occurred were considered to indicate intent to vaccinate. The composite outcome of vaccination or intent to vaccinate – referred to as “vaccination rate” – was calculated by dividing the number of children reported to have been vaccinated or for whom a vaccination appointment was scheduled by the number of children for whom a response was obtained. Parents were also asked about their own vaccination practices and how they obtained information about health in general, and influenza specifically. Only children aged >6 months with ACIP-high-risk conditions were included in the analysis.

2.2. Healthcare provider survey

CDC also collaborated with the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) to recruit primary care and specialty physicians who provide care for high-risk children, specifically those with neurologic conditions. Physicians were recruited through AAP specialty listservs including the Council on Children with Disabilities, the Council on Practice Management, the Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics and the Section on Neurology. An on-line survey was available from March 7 to May 15, 2011. This survey collected basic demographic information including practice setting and specialty as well as influenza vaccination practices for various patient populations. Specifically, respondents were provided with a list of high-risk conditions and were asked: “Based on your clinical opinion or expertise, pediatric patients with which of the following conditions are at higher risk for complications (hospitalizations or death) from flu?” Respondents were also asked to report the two most prevalent chronic conditions among patients seen in their practice.

2.3. Survey development

Survey items about influenza and influenza vaccination beliefs and practices were modeled after existing instruments used in national immunization surveys. The target diagnoses of interest were based on high-risk conditions for severe influenza observed during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic as defined by a joint CDC/AAP working group on children at-risk for influenza complications. Expert opinion was sought from the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases and both surveys were pilot tested with 10 respondents prior to dissemination.

2.4. Data analysis

For each survey, descriptive statistics were summarized as percentages. Between-group differences were assessed using chi-square testing. In the parent survey, logistic regression models were used to assess associations between influenza vaccination and specific high-risk conditions to adjust for the presence of multiple co-occurring conditions. These models also adjusted for vaccination of the child against seasonal influenza during prior years and interview completion in Spanish, based on a priori assumptions that these factors would be associated with intent to vaccinate during the current season. We chose Spanish language as a covariate as Hispanic children are more likely to receive influenza vaccine as compared to non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black children [12]. Survey items with response rates less than 90% are presented as descriptive results but were not included in multivariable analysis. Interaction terms between respiratory diagnoses and each NNDD were also explored. In the healthcare survey, a secondary analysis was performed assessing recognition of high-risk conditions only among those providers who reported caring for children with the specific condition.

A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Stata Version 12 (Statacorp, College Station, TX) was used for statistical analysis. The protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Oak Ridge Site-wide Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

3.1. Parent survey

3.1.1. Child characteristics

2138 surveys were completed by parents of children with 4045 high-risk conditions for a median of one condition per child. 1143 (53%) children had at least one NNDD; 516 had more than one. Specific diagnoses included 950 children with intellectual disability (ID), 359 with epilepsy (EP), and 271 with cerebral palsy (CP). 524/2138 (25%) children had at least one underlying chronic respiratory condition including 455 with asthma, 60 with bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and 85 with other chronic lung diseases (such as cystic fibrosis). Of these 524 children, 264 (50%) also had at least one NNDD; 227 had ID, 101 had EP, and 89 had CP. Other reported conditions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Percentage of underlying chronic medical conditions based on parental surveys (n = 2138).

| Diagnosis | n (%)a |

|---|---|

| Neurologic/neurodevelopmental | |

| Intellectual disability | 950 (44) |

| Epilepsy | 359 (17) |

| Cerebral palsy | 271 (13) |

| Stroke | 64 (3) |

| Spinal cord | 41 (2) |

| Other brain conditions | 279 (13) |

| Respiratory | |

| Asthma | 455 (21) |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 60 (3) |

| Other chronic lung disease | 85 (4) |

| Hematologic/oncologic | |

| Cancer | 34 (2) |

| Other blood | 45 (2) |

| Sickle cell disease | 25 (1) |

| Other | |

| Genetic | 345 (16) |

| Prematurity | 217 (10) |

| Weakened immune | 141 (7) |

| Metabolic | 139 (7) |

| Heart | 136 (7) |

| Endocrine | 107 (5) |

| Obesity | 99 (5) |

| Musculoskeletal | 69 (3) |

| Kidney | 65 (3) |

| Liver | 30 (1) |

| Chronic aspirin use | 29 (1) |

Totals do not add to 100%.

Children could have more than one condition.

3.1.2. Vaccination status

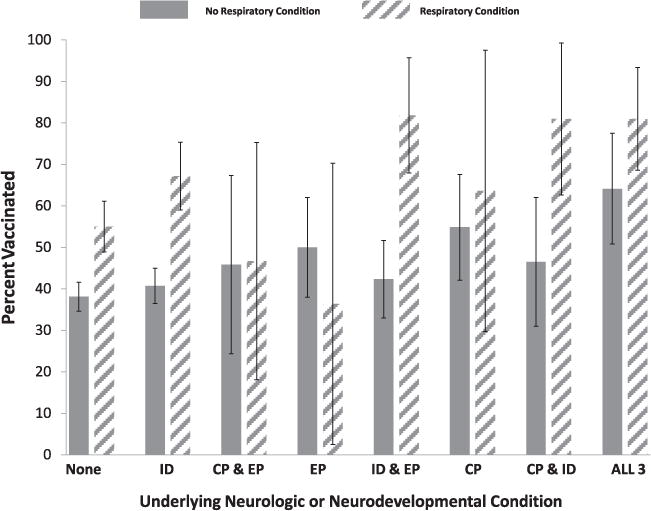

Overall, 998 (47%) of respondents reported that their child had received (n = 896), or was scheduled to receive (n = 102) seasonal influenza vaccine. Children with NNDDs had slightly higher rates (50 versus 43%, p = 0.0003) of vaccination than other children with high-risk conditions. A major driver of influenza vaccination was the presence of a chronic respiratory condition. Children with one or more chronic respiratory conditions were more likely to be vaccinated (62%) as compared to those without such a condition (42%, p < 0.0001). To account for the potential impact of respiratory conditions we stratified reported influenza vaccination rates for specific NNDD by the presence of a concomitant respiratory condition. Influenza vaccination rates for children with CP, EP, and ID with and without a respiratory condition are presented in Fig. 1. In univariate analyses, the presence of a respiratory condition was associated with statistically significant higher influenza vaccination rates for children with no NNDDs, children with ID alone, children with ID and EP, children with CP and ID, and children with all three conditions.

Fig. 1.

Parental report of vaccination, or intent to vaccinate, stratified by neurologic/neurodevelopmental and respiratory conditions. None, no neurodevelopmental disability; ID, intellectual disability; CP, cerebral palsy; EP, epilepsy: ALL, ID, CP and EP. Bars indicate 95th percentile confidence intervals.

711 children (71%) who received influenza vaccine did so in their primary care physician’s office, and 48 (5%) were vaccinated at a subspecialist’s office. Vaccination in hospitals, health departments, pharmacies, schools, or other community-based settings was less common. Presence of a NNDD was not associated with location of vaccine receipt (data not shown).

1041, or 49% of, parents of children with NNDDs reported that they considered their child to be at increased risk for developing complications from influenza. Parental perception of risk by condition is summarized in Table 2. In general, the parents of children with respiratory conditions were more likely to see their children as high-risk. Although 72% of parents of children with CP considered their children to be at high-risk, perception of risk was less common for EP (64%) and ID (54%). Children perceived by their parents to be at high risk were more likely to be vaccinated than children of parents who responded “no” or “do not know” (65 vs 34%, p < 0.0001). Children who had previously received seasonal influenza vaccine were more likely (67 vs 20%, p< 0.0001) than previously unvaccinated children to be vaccinated during the 2011–2012 season. Similarly, parents who had received influenza vaccine during the current season were much more likely to have their children vaccinated (87 vs 25%, p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Percentage of parents who reported their children are at high-risk of complications from influenza, by condition.

| Diagnosis | Parental perception of condition as high risk(%) |

|---|---|

| Neurologic/neurodevelopmental | |

| Intellectual disability | 54 |

| Epilepsy | 64 |

| Cerebral palsy | 72 |

| Stroke | 53 |

| Spinal cord | 49 |

| Other brain conditions | 59 |

| Respiratory | |

| Asthma | 75 |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 83 |

| Other chronic lung disease | 82 |

| Hematologic/oncologic | |

| Cancer | 56 |

| Other blood | 58 |

| Sickle cell disease | 56 |

| Other | |

| Genetic | 70 |

| Prematurity | 72 |

| Weakened immune | 69 |

| Metabolic | 52 |

| Heart | 77 |

| Endocrine | 72 |

| Obesity | 53 |

| Musculoskeletal | 67 |

| Kidney | 62 |

| Liver | 63 |

| Chronic aspirin use | 65 |

To better understand the relationship between specific underlying diagnoses and likelihood of vaccination we constructed logistic regression models, including an interaction term for the association between respiratory diagnoses and the other diagnoses of interest, adjusting for the child’s receipt of seasonal influenza vaccine in previous years and language of survey. In this analysis, influenza vaccination status was independently associated with receipt of seasonal influenza vaccine in previous years (OR 7.5, 95% CI 6.2–9.4), presence of a chronic respiratory condition (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1–2.0), and completing the interview in Spanish (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–2.9). The presence of CP, EP, or ID was not associated with vaccination. Only the interaction term between respiratory condition and ID was statistically significant (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.1–3.0). This implies that the presence of a concomitant respiratory condition had a multiplicative impact on likelihood of vaccination for children with ID, but not CP or EP.

3.1.3. Reasons for vaccine refusal

1140 parents reported that they did not intend to vaccinate their child against influenza. Of these, 892 (78%) provided a reason. The most commonly reported reasons for deferring influenza vaccination were:

“Concerns about how the vaccine would affect my child” (38%).

“Concerns about the safety of the vaccine” (32%).

“Don’t believe the vaccine protects against the flu” (15%).

“Health care provider did not recommend” (7%).

3.1.4. Sources of information

Healthcare providers were by far the most common (75%) source of information about vaccines in general and influenza vaccine specifically. Parents of vaccinated children were more likely than parents of unvaccinated children (80 vs 64%, p < 0.0001) to use healthcare providers as a source of information. Use of the internet (24%) and family support or disability advocacy organizations (21.7%) was less frequent and did not differ between families of vaccinated and unvaccinated children. Parents who believed their child was at increased risk for complications from influenza used similar sources of information as those who did not believe their child was at increased risk for complications (data not shown).

3.2. Healthcare provider survey

3.2.1. Physician characteristics

Of 412 physicians who participated in the on-line survey, 214 (52%) were male and the median age was 52 years. The median number of years in practice at the time of survey participation was 19 years. 183 (44%) respondents identified themselves as primary care providers. Among the remaining physicians the most represented specialties were neurology (65, 16%), emergency medicine (56, 14%), critical care (28, 7%) and genetics/metabolism (24, 6%). 97% of respondents reported that they had been vaccinated against influenza during the preceding influenza season.

3.2.2. Vaccination practices

The responses from the 393 physicians who completed the question about high-risk influenza conditions are summarized in Table 3. Cerebral palsy was recognized as a high-risk condition by 74% of physician respondents, but epilepsy (51%) and intellectual disability (46%) were less commonly identified. Recognition of specific high-risk conditions among those physicians who reported treating children with those conditions are presented in Table 4. Nearly all physicians who cared for children with asthma reported it as a high-risk condition. Although recognition of cerebral palsy (79%), epilepsy (72%) and intellectual disability (55%) as high-risk conditions was higher among physicians who primarily treated these conditions as compared to all survey respondents, it remains suboptimal.

Table 3.

Percentage of physicians (n = 393) who rated conditions as high-risk for complications from influenza.

| Diagnosis/indication | Percent of physician respondents (n=393) rating condition as high-risk for complications from influenza |

|---|---|

| Other chronic lung diseases | 95 |

| Asthma | 94 |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 93 |

| Heart | 90 |

| Weakened immune | 90 |

| Muscular system disorder | 85 |

| Metabolic disease | 78 |

| Sickle cell disease | 77 |

| Prematurity | 76 |

| Cancer | 74 |

| Cerebral palsy | 74 |

| Spinal condition | 71 |

| Endocrine | 66 |

| Genetic | 65 |

| Obesity | 64 |

| Aspirin use | 59 |

| Other brain disorders | 56 |

| Kidney | 56 |

| Stroke (CVA) | 56 |

| Liver | 52 |

| Epilepsy | 51 |

| Intellectual disability | 46 |

| Other blood disorders | 40 |

Table 4.

Rating of specific conditions as high-risk for development of influenza complications among physicians who reported treating children with the condition.

| Diagnosis/indication | Percent of all physician respondents (n=393) rating condition as high-risk | Number (%) of physicians who report condition is prevalent in their practice | Percent of these physicians who rate condition as high-risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | 94 | 247 (63) | 99 |

| Prematurity | 76 | 43 (11) | 93 |

| Cerebral palsy | 74 | 63 (16) | 79 |

| Obesity | 64 | 51 (13) | 78 |

| Epilepsy | 51 | 77 (20) | 72 |

| Intellectual disability | 46 | 77 (20) | 55 |

4. Discussion

Annual influenza vaccination is recommended for all children aged ≥6 months in the U.S, with emphasis on those children in certain high-risk groups [13]. However, influenza vaccine coverage among children has been modest – with approximately half of all eligible children vaccinated during the 2011–2012 influenza season [12]. Our data from the same influenza season suggest similar vaccine uptake among children with NNDDs despite the fact that they are at increased risk for poor outcomes from influenza.

Although several studies have demonstrated that children with NNDDs are at increased risk of complications from influenza, the reasons for this increased severity of influenza among this population are uncertain. Keren et al. assessed medical conditions associated with respiratory failure in a cohort of children hospitalized with complications associated with seasonal influenza at a large tertiary care hospital from 2000–2004 [4]. These authors reported that the presence of a neurological or neuromuscular disorder was an independent risk factor for respiratory failure. However, seizure disorder alone was not associated with respiratory failure in secondary analysis and the authors concluded that conditions associated with poor pulmonary toilet, rather than an underlying neurologic process per se, led to respiratory failure. The pathophysiology of increased risk of severe influenza for children with ID is less clear, and may be due to the presence of other co-occurring conditions. Nevertheless, ID was the most common NNDD associated with death during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and therefore a better understanding of the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors influencing influenza vaccination of children with ID is essential.

Low influenza vaccine coverage among children with neurologic and neurodevelopmental conditions is partly due to lack of recognition of underlying conditions in children that increase the risk for influenza complications by both providers and parents. In the parent survey described here, only 54% of parents of children with ID considered their child to be at increased risk for developing complications from influenza. At the same time, only 46% of physicians recognized ID as a high-risk condition for influenza complications. While this number was slightly higher among physicians who primarily care for children with ID, clearly more education of providers is indicated, especially as healthcare providers are the most common source of information about influenza and influenza vaccination.

Concerns about vaccine safety were also prevalent in our parent population. 38% of parents whose children were unvaccinated had concerns about how influenza vaccine would affect their children. An additional 32% had concerns about the safety of the vaccine. These results are consistent with previous surveys administered to parents of high-risk children [8–10]. In these studies, which did not include children with NNDDs, concerns about vaccine safety, notably acquisition of influenza virus infection from vaccination, were associated with decreased likelihood of vaccination. Specific parental influenza vaccine safety concerns were not addressed in the current study. Concomitantly conducted focus groups with parents of children with NNDDs may shed light on the specifics of these concerns, and will be reported separately.

It is reassuring that both parents and physicians recognized chronic respiratory conditions as risk factors for severe influenza. This is likely due to the more obvious role of a respiratory virus as a trigger for exacerbations of respiratory conditions such as asthma. Additionally, asthma has been considered a high-risk ACIP condition for influenza complications since the 1960s [13]. In contrast, NNDDs have been considered high-risk influenza conditions for less than a decade. We attempted to distinguish the impact of an underlying respiratory condition from an underlying NNDD on parental intent to vaccinate using a regression model. In our analysis, presence of an underlying respiratory condition was associated with vaccination but presence of an NNDD was not. Of note, there was a significant interaction between an underlying respiratory condition and presence of ID. This is most likely because ID was the NNDD least likely to be seen as a high-risk diagnosis.

As the pathophysiology of severe influenza in this population becomes clearer, influenza vaccination coverage among children with NNDDs may rise. In the meantime, it is critical to educate both parents and medical providers of the natural history of influenza in this patient population. Public health campaigns should target the specific concerns of parents of children with NNDDs, and any messaging needs to be pretested within this population. It is equally important to educate physicians about the risks of influenza in children with NNDDs as they may be unaware of the severe influenza illness observed in this population. A strong physician recommendation for vaccination may the single most important factor in parental decision making surrounding influenza vaccination. Indeed, prior studies have shown that physicians are the most highly trusted sources of information about vaccinations in general, even for parents with vaccine safety concerns [14,15]. Our data suggest that this holds true for parents of children with NNDDs, as well.

A limitation is that the results of both surveys are based on self-report and may not reflect actual influenza vaccination practices. However, we are unaware of any nationally representative reports of provider-verified vaccination for children with NNDDs. If anything, parental report of influenza vaccination has been shown to result in overestimation of vaccine coverage [16]. If this occurred in the present study, the need for outreach is even greater than suggested by our results. Another concern is that the physicians who participated in the healthcare provider survey were not the same physicians who treated the families in the parent survey, and their responses might not be representative of the experiences the caregivers had with their own health care providers. Because physicians were consistently reported to be the most commonly used source of information, it is informative to juxtapose these data with the parent survey. Selection bias is also possible as both the healthcare provider and caregiver surveys were distributed via listserv services. We are therefore unable to calculate the survey response rate or compare characteristics of respondents and non-respondents. As a result, physicians especially interested in influenza prevention and treatment may have been over represented in the sample, given the high (97%) reported influenza vaccination among the physician respondents. Again, this would bias our results toward greater physician awareness of influenza prevention, and the low recognition of NNDDs as high-risk conditions becomes even more concerning. Finally, we may not have accounted for all potential confounders in our multivariable analysis. Physician recommendation, which is a key factor in parental decision making around vaccines, was not fully captured in the survey and other factors, such as parental risk perception and parental vaccination status, were not included in the model due to missing data.

5. Conclusions

We present the first estimates of seasonal influenza vaccination among children with NNDDs, and a preliminary view of the influenza vaccine-related attitudes, beliefs, and practices of parents and healthcare providers of these children. Although children with NNDDs are at increased risk of influenza complications, our estimates of influenza vaccination are similar to published reports of vaccine coverage in healthy children. Education of parents and healthcare providers about influenza and the benefits of annual influenza vaccination is critical to protect this vulnerable patient population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dick Tardif, Janice Watkins and Adina de Coteau from ORISE for their assistance in survey design and preliminary data analyses. The authors also thank staff from Family Voices and the American Academy of Pediatrics for their assistance in survey distribution.

Funding

This research was performed in cooperation with the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflict of interest: M.J.S. has received research support for vaccine clinical trials from Sanofi and Novartis. All authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza – United States, 1976–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Bridges CB, Cox NJ, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;292:1333–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harper SA, Fukuda K, Uyeki TM, Cox NJ, Bridges CB. Prevention and control of influenza. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keren R, Zaoutis TE, Bridges CB, Herrera G, Watson BM, Wheeler AB, et al. Neurological and neuromuscular disease as a risk factor for respiratory failure in children hospitalized with influenza infection. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294:2188–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.17.2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson CO, Graham DA, Uyeki TM, Randolph AG. Risk factors for mechanical ventilation in US children hospitalized with seasonal influenza and 2009 pandemic influenza A. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:625–31. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318260114e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong KK, Jain S, Blanton L, Dhara R, Brammer LL, Fry AM, et al. Influenza-associated pediatric deaths in the United States, 2004–2012. Pediatrics. 2013;132:796–804. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanton L, Peacock G, Cox C, Jhung M, Finelli L, Moore C. Neurologic disorders among pediatric deaths associated with the 2009 pandemic influenza. Pediatrics. 2012;130:390–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin CJ, Nowalk MP, Zimmerman RK, Ko FS, Zoffel L, Hoberman A, et al. Beliefs and attitudes about influenza immunization among parents of children with chronic medical conditions over a two-year period. J Urban Health. 2006;83:874–83. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9084-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin CJ, Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Ko FS, Raymund M, Hoberman A, et al. Parental perspectives on influenza vaccination of children with chronic medical conditions. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:148–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirza A, Subedar A, Fowler SL, Murray DL, Arnold S, Tristram D, et al. Influenza vaccine: awareness and barriers to immunization in families of children with chronic medical conditions other than asthma. South Med J. 2008;101:1101–5. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318182ee8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dombkowski KJ, Leung SW, Clark SJ. Provider attitudes regarding use of an immunization information system to identify children with asthma for influenza vaccination. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13:567–71. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000296131.77637.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flu Vaccination Coverage, United States, 2012–13 Influenza Season. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1213estimates.htm#references.

- 13.Vaccination coverage among persons with asthma – United States, 2010–2011 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:973–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith PJ, Kennedy AM, Wooten K, Gust DA, Pickering LK. Association between health care providers’ influence on parents who have concerns about vaccine safety and vaccination coverage. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1287–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salmon DA, Moulton LH, Omer SB, DeHart MP, Stokley S, Halsey NA. Factors associated with refusal of childhood vaccines among parents of school-aged children: a case-control study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:470–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown C, Clayton-Boswell H, Chaves SS, et al. Validity of parental report of influenza vaccination in young children seeking medical care. Vaccine. 2011;29:9488–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]