Abstract

Kidney allograft rejection can occur in clinically stable patients, but long-term significance is unknown. We determined whether early recognition of subclinical rejection has long-term consequences for kidney allograft survival in an observational prospective cohort study of 1307 consecutive nonselected patients who underwent ABO-compatible, complement-dependent cytotoxicity-negative crossmatch kidney transplantation in Paris (2000–2010). Participants underwent prospective screening biopsies at 1 year post-transplant, with concurrent evaluations of graft complement deposition and circulating anti-HLA antibodies. The main analysis included 1001 patients. Three distinct groups of patients were identified at the 1-year screening: 727 (73%) patients without rejection, 132 (13%) patients with subclinical T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR), and 142 (14%) patients with subclinical antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR). Patients with subclinical ABMR had the poorest graft survival at 8 years post-transplant (56%) compared with subclinical TCMR (88%) and nonrejection (90%) groups (P<0.001). In a multivariate Cox model, subclinical ABMR at 1 year was independently associated with a 3.5-fold increase in graft loss (95% confidence interval, 2.1 to 5.7) along with eGFR and proteinuria (P<0.001). Subclinical ABMR was associated with more rapid progression to transplant glomerulopathy. Of patients with subclinical TCMR at 1 year, only those who further developed de novo donor-specific antibodies and transplant glomerulopathy showed higher risk of graft loss compared with patients without rejection. Our findings suggest that subclinical TCMR and subclinical ABMR have distinct effects on long-term graft loss. Subclinical ABMR detected at the 1-year screening biopsy carries a prognostic value independent of initial donor-specific antibody status, previous immunologic events, current eGFR, and proteinuria.

Keywords: renal medicine, transplant rejection, allograft loss, allograft function, translational research

Kidney transplantation is the best possible treatment for many patients with end stage renal failure, but progressive dysfunction and allograft loss with return to dialysis are associated with increased mortality and morbidity.1,2 The alloimmune injury induced by transplantation from a donor who differs genetically from the kidney recipient is recognized as the leading cause of kidney transplant failure,3–5 making this injury a key target for further expected and necessary progress in the field of transplantation.

There has been growing awareness in the transplant community over the last decade of the profound changes in the spectrum of clinical expression of allograft rejection.6,7 The rejection phenotypes seen today are more complex than they were previously, with blatant rejection replaced by subtler or indolent forms8 not recognizable by conventional tests used for graft function monitoring.

The term subclinical rejection of kidney allografts was coined in the 1990s,9 and it has had a varying incidence ranging from 15% to 50%10,11; however, it took another decade to show the association of subclinical rejection with the development of long-term decline in graft function.12 Subclinical rejection was initially attributed to a unique T cell-mediated process, but recent findings have challenged the notion of a unique T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) process with the demonstration of subclinical antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR).13 This concept has gained momentum with the increasing use of specific therapies in patients undergoing transplantation across HLA barriers.14 Importantly, these findings have been extended to the transplantation of hearts15,16 and other solid organs,17,18 pointing toward a general observation of increasing antibody-mediated damage after transplantation.

Small-scale studies performed to date have suggested that subclinical rejection and more specifically, subclinical ABMR may be related to allograft outcomes and accelerated progression to chronic antibody-mediated injury.13,19,20 These suggestions led international allograft rejection classification experts to discuss, at the 12th Banff Conference on Allograft Pathology in August of 2013, the recognition of subclinical ABMR as part of the spectrum of ABMR. However, there are no large-scale data regarding the incidence of subclinical ABMR and no demonstration of the long-term consequences of this diagnosis with regard to allograft injury and survival.

Here, we hypothesized that subclinical rejection can be identified early (in the first year post-transplantation) in kidney recipients who have neither clinical nor laboratory evidence of rejection, which may have important clinical implications for graft survival. We, thus, aimed to define subclinical rejection patterns by addressing their distinct phenotypes and their associated prognoses in a large population-based study of kidney transplant recipients, in whom screening allograft biopsies were prospectively performed at 1 year after transplantation.

Results

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

In total, 1001 patients were included in the main analysis (Table 1). We identified three distinct populations according to the screening biopsy phenotype at 1 year: (1) patients without rejection (n=727; 72.6%), (2) patients with subclinical TCMR (n=132; 13.2%), and (3) patients with subclinical ABMR (n=142; 14.2%). Among the patients without rejection, 80 (11%) patients showed acute tubular necrosis, 35 (4.8%) patients exhibited borderline lesions that were deemed to not be TCMR, 55 (7.5%) patients showed calcineurin inhibitor toxic effects, 39 (5.4%) patients had recurrent disease, 26 (3.6%) patients had viral nephropathy, 160 (22%) patients had interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, 61 (8.4%) patients had other diagnoses, and the remaining 246 (33.8%) patients were defined as having no major abnormalities. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the donors and recipients at the time of renal transplantation according to kidney allograft phenotype.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Patient Characteristics | Overall Population (n=1001) | No Rejection (n=727) | Subclinical TCMR (n=132) | Subclinical ABMR (n=142) | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Value | N | Value | N | Value | N | Value | ||

| Recipient age (yr) | 1001 | 47.9±13 | 727 | 47.5±13.4 | 132 | 47.7±13.4 | 142 | 49.8±12.4 | 0.16 |

| Recipient sex (men), n (%) | 994 | 582 (59) | 721 | 421 (58) | 132 | 88 (67) | 141 | 73 (13) | 0.04 |

| Retransplantation, n (%) | 1001 | 190 (19) | 727 | 117 (16) | 132 | 16 (12) | 142 | 57 (40) | <0.001 |

| Time since dialysis (yr) | 866 | 5.04±4.4 | 623 | 4.9±4.3 | 114 | 4.6±0.3 | 129 | 6.1±5.2 | 0.009 |

| Donor age (yr) | 991 | 50±16 | 718 | 50±16 | 131 | 51±17 | 141 | 51±16 | 0.74 |

| Donor sex (men), n (%) | 979 | 553 (56) | 710 | 402 (57) | 131 | 72 (55) | 138 | 79 (57) | 0.92 |

| Deceased donor, n (%) | 1001 | 819 (82) | 727 | 519 (71) | 132 | 116 (88) | 142 | 124 (87) | 0.02 |

| Cardiovascular cause of donor death, n (%) | 1001 | 446 (45) | 727 | 311 (43) | 132 | 68 (52) | 142 | 67 (47) | 0.14 |

| Cold ischemia time (h) | 970 | 19±10 | 701 | 18±10 | 130 | 19±9 | 139 | 21±10 | 0.004 |

| Delayed graft function, n (%) | 995 | 219 (22) | 722 | 149 (21) | 132 | 36 (27) | 141 | 34 (24) | 0.19 |

| Graft survival,a n (%) | 1001 | 865 (86) | 727 | 646 (89) | 132 | 111 (84) | 142 | 99 (70) | <0.001 |

| Patient survival,a n (%) | 1001 | 928 (93) | 727 | 680 (94) | 132 | 122 (92) | 142 | 126 (89) | 0.13 |

| Follow-up (yr) | 1001 | 4.7±2.1 | 4.7±2.1 | 132 | 5.2±2.1 | 142 | 4.2±1.8 | <0.001 | |

| Causal nephropathy, n (%) | 1001 | 727 | 132 | 142 | |||||

| Diabetes | 85 (8.5) | 64 (9) | 13 (10) | 8 (6) | |||||

| Vascular | 68 (6.8) | 46 (6) | 11 (8) | 11 (8) | |||||

| Glomerulopathy | 316 (31.6) | 226 (31) | 47 (36) | 43 (30) | |||||

| Congenital | 205 (20.4) | 156 (21) | 24 (18) | 25 (17) | |||||

| Other | 7 (0.7) | 5 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |||||

| Interstitial nephropathy | 123 (12.3) | 85 (12) | 15 (11) | 23 (16) | |||||

| Undetermined | 197 (19.7) | 145 (20) | 21 (16) | 31 (22) | 0.78 | ||||

| Immunology | |||||||||

| HLA A+B mismatch | 986 | 2.0±1.1 | 715 | 2.0±1.1 | 131 | 2.1±1.0 | 140 | 2.0±1.1 | 0.62 |

| HLA DR mismatch | 987 | 0.8±0.7 | 715 | 0.8±0.7 | 132 | 0.8±0.6 | 140 | 0.8±0.6 | 0.66 |

| Lymphocytotoxic panel reactive antibidies | 986 | 3.1±3.3 | 715 | 0.9±1.0 | 132 | 5.1±4.8 | 140 | 25.9±20.7 | <0.001 |

| Anti-HLA DSA at day 0 | 1001 | 229 (22.9) | 727 | 106 (14) | 132 | 12 (9) | 142 | 111 (78) | <0.001 |

| Recipient blood group type A/B/O/AB | 968 | 438/75/425/30 | 703 | 306/54/327/16 | 128 | 62/12/9/45 | 137 | 70/9/5/53 | <0.001 |

The data are from the Données Informatiques Validées en Transplantation database.33 All of the P values were determined by the chi-squared test for comparison of proportions and the unpaired t test for comparison of continuous variables. Values are means±SDs unless indicated otherwise.

Last follow-up: April 15, 2012.

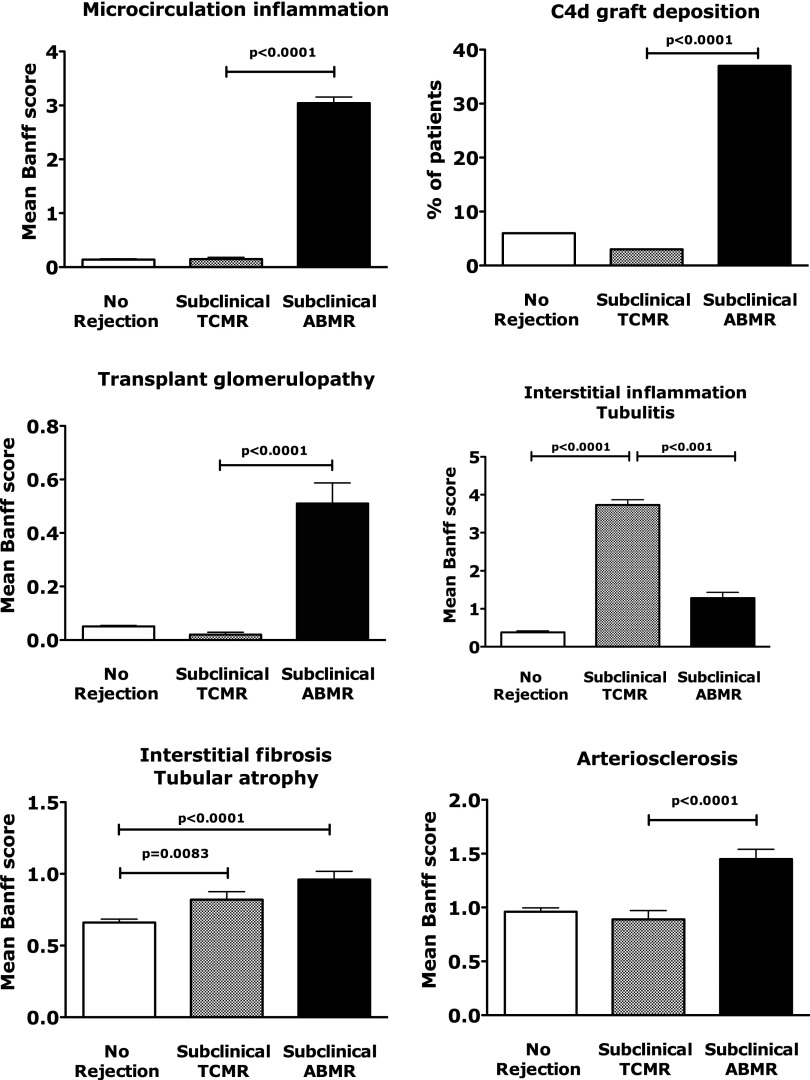

Kidney Allograft and Immunologic Phenotypes at 1 Year

All of the patients with subclinical ABMR exhibited microcirculation inflammation (glomerulitis and capillaritis lesions), 52 (37%) patients exhibited minimal tubular and interstitial inflammation, 6 (4%) patients had endarteritis lesions, 72 (51%) patients exhibited moderate to severe arteriosclerosis, 29 (20%) patients suffered from moderate to severe atrophy-scarring lesions, and 45 (32%) patients exhibited C4d deposition in peritubular capillaries. Patients with subclinical ABMR exhibited greater microcirculation inflammation and transplant glomerulopathy and had higher graft peritubular capillary C4d deposition scores compared with both the subclinical TCMR and nonrejection groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distinct allograft injury phenotypes in 1 year screening kidney allograft biopsies. Graft injury phenotype in screening allograft biopsies performed at 1 year post-transplant (n=1001). Results are given as Banff scores for each lesion. Bars represent SEMs.

All patients with subclinical ABMR had donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) at the time of the screening biopsy. The mean DSA maximum mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was 2550±580. The highest ranked DSA was class II in 103 of 142 (72.5%) patients with subclinical ABMR, whereas in 39 of 142 (27.5%) patients with subclinical ABMR, the highest ranked DSA was class I.

Among patients with subclinical ABMR, 111 (78%) patients had preexisting DSAs, whereas the remaining 31 (22%) patients had de novo DSAs.

In total, 17 of 132 (12.9%) patients with subclinical TCMR had detectable DSAs at the time of diagnosis (mean DSA maximum MFI of 980±492). Finally, among 534 patients without rejection with analyzable sera, 97 (18.2%) patients had detectable DSAs at the time of the 1-year screening biopsy (mean DSA maximum MFI of 1041±970).

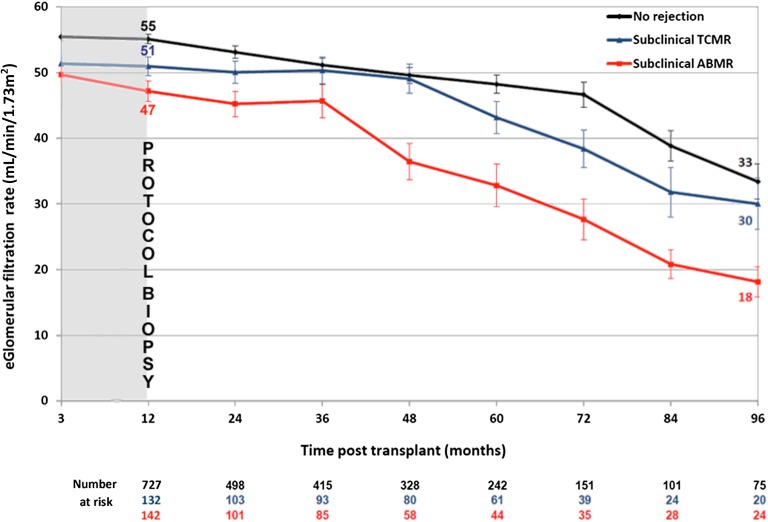

Kidney Allograft Function and Injury According to Subclinical Rejection Phenotype

The course of kidney allograft function according to subclinical rejection phenotypes was determined using 4.511 longitudinal eGFRs assessed over 8 years post-transplant. Linear mixed model analysis showed that patients with subclinical ABMR exhibited a faster decline of GFR over time compared with patients with subclinical TCMR and patients without rejection (Figure 2). In contrast, patients exhibiting subclinical TCMR had similar profiles of long-term GFR decline compared with patients without rejection (P=0.74).

Figure 2.

Distinct kidney allograft function course according to the 1 year screening kidney allograft biopsies phenotype. Long-term kidney allograft function according to 1-year subclinical rejection profile. The evolution of eGFR in 1001 patients on the basis of assessment of 4.511 longitudinal eGFRs is shown. We evaluated the long-term course of eGFR in three groups of patients by using a linear mixed model starting from 1 year post-transplant to the last available eGFR; 905 eGFR measurements taken at 3 months post-transplant are also shown. Bars represent SDs.

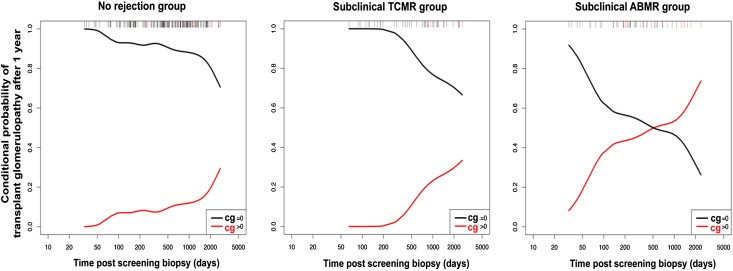

Among 317 for-cause biopsies performed after 1 year post-transplant, 210 biopsies were in the nonrejection group, 51 biopsies were in the subclinical TCMR group, and 56 biopsies were in the subclinical ABMR group. The conditional probability of occurrence of transplant glomerulopathy lesions 1000 days after the 1-year screening biopsy (reflecting the probability of having transplant glomerulopathy (TG) lesions conditional to having a biopsy for cause after 1 year post-transplant) was 12% in the nonrejection group, 22% in the subclinical TCMR group, and 54% in the subclinical ABMR group (Figure 3). Details of the Banff lesion scores in for cause biopsies performed before and after 1 year are given in Supplemental Table 2.

Figure 3.

Distinct time frame of progression of transplant glomerulopathy lesions according to the 1 year screening kidney allograft biopsies phenotype. Conditional probability of occurrence of transplant glomerulopathy lesions in three groups of patients. The conditional probability plot integrates all biopsies for cause taken after 1 year (n=316) and assesses the cg Banff score of each biopsy. Note that, for three groups, the probability of developing cg lesions after 1 year is conditional on having a biopsy for cause performed after 1 year. This does not represent the overall or absolute probability of developing transplant glomerulopathy (cg) lesions after 1 year.

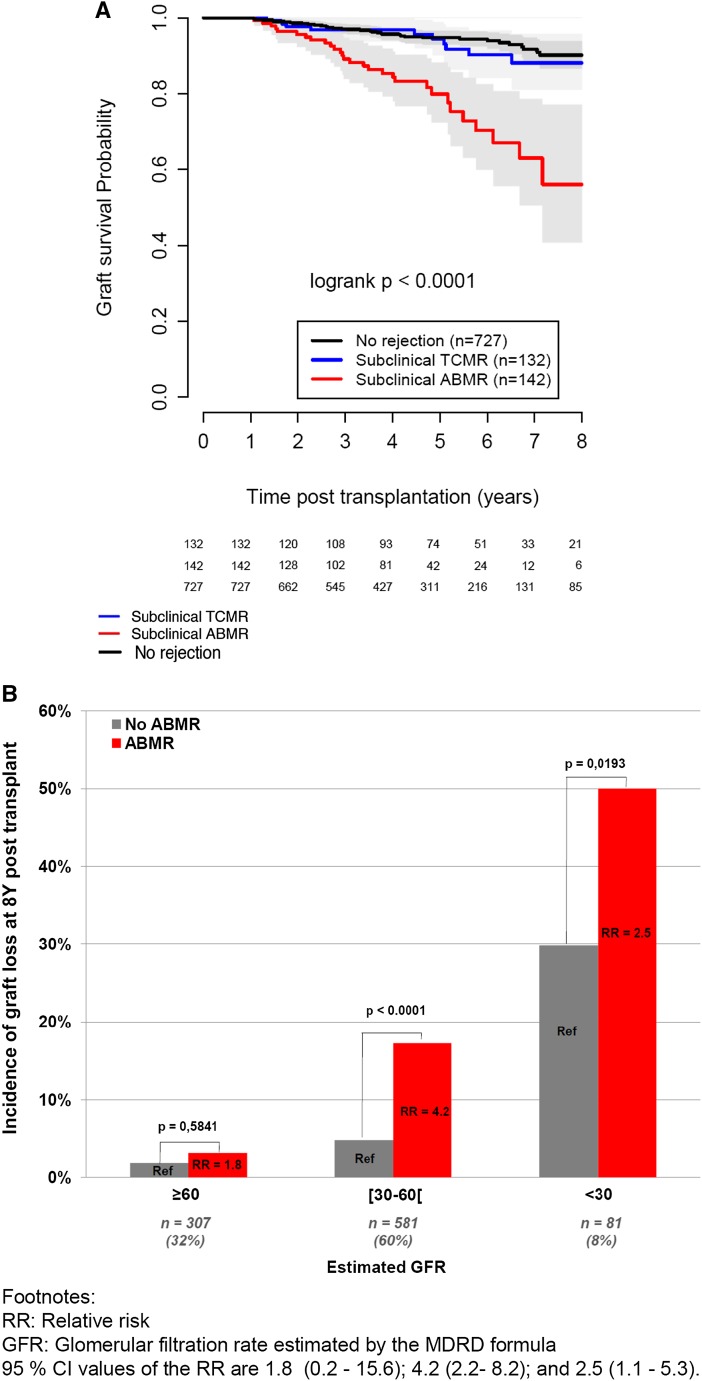

Kidney Allograft Loss According to Subclinical Rejection Phenotype

The median follow-up after transplantation was 4.6 years (25%–75% interquartile range [IQR]=0.24–8.0) for all three groups, whereas it was 4.2 years (IQR=2.9–5.2) in the subclinical ABMR group, 5.2 years (IQR=3.7–6.9) in the subclinical TCMR group, and 4.6 years (IQR=3.0–6.4) in the nonrejection group (P=NS).

Patients with subclinical ABMR exhibited worse graft survival than patients with subclinical TCMR and patients without rejection: 8-year graft survival of 56% compared with 88% and 90%, respectively (P<0.001) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Long-term allograft survival according to the one-year biopsy phenotype. (A) Graft survival probability, according to the rejection profile: subclinical ABMR, subclinical TCMR, or no rejection. (B) Risk of kidney allograft loss according to eGFR and the presence of subclinical ABMR. GFR was estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula. Relative risks (RRs) and 95% CIs are 1.8 (0.2 to 15.6), 4.2 (2.2 to 8.2), and 2.5 (1.1 to 5.3).

The associations of clinical, functional, histologic, and immunologic parameters with graft loss are shown in Table 2. The univariate significant predictors (P<0.05) of graft loss were donor age (P=0.01), cold ischemia time (P=0.01), graft rank (P=0.05), delayed graft function (P=0.008), eGFR at 1 year (P<0.001), degree of graft atrophy scarring (P<0.001), C4d graft deposition (P<0.001), subclinical ABMR (P<0.001), previous rejection episodes (P=0.005), presence of DSAs at 1 year (P<0.001), and proteinuria at 1 year (P<0.001).

Table 2.

Univariate associations of clinical, functional, histologic, and immunologic parameters with kidney graft loss

| Parameters | Number of Patients | Number of Events | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor and recipient parameters | |||||

| Recipient age (yr) | 1001 | 77 | 1.01 | 0.99 to 1.03 | 0.21 |

| Recipient sex | |||||

| Men | 582 | 49 | 1 | — | — |

| Women | 412 | 28 | 0.81 | 0.51 to 1.28 | 0.37 |

| Donor age (yr) | 990 | 75 | 1.02 | 1.00 to 1.04 | 0.01 |

| Donor sex | |||||

| Men | 553 | 40 | 1 | — | — |

| Women | 426 | 34 | 1.11 | 0.70 to 1.75 | 0.65 |

| Donor type | |||||

| Living | 182 | 8 | 1 | — | — |

| Deceased | 819 | 69 | 1.87 | 0.9 to 3.9 | 0.09 |

| Allograft characteristics | |||||

| Cold ischemia time (min) | 970 | 76 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 0.01 |

| Graft rank | |||||

| First transplantation | 811 | 55 | 1 | — | — |

| Retransplantation | 190 | 22 | 1.65 | 1.0 to 2.7 | 0.05 |

| HLA A/B/DR mismatch | 988 | 76 | 1.1 | 0.9 to 1.3 | 0.31 |

| Delayed graft function | |||||

| No | 776 | 48 | 1 | — | — |

| Yes | 219 | 27 | 1.9 | 1.2 to 3.0 | 0.008 |

| Clinical parameters | |||||

| eGFR at 1 yr, ml/min | |||||

| eGFR≥60 | 307 | 6 | 1 | — | — |

| 30≤eGFR<60 | 581 | 38 | 3.4 | 1.5 to 8.2 | <0.001 |

| eGFR<30 | 81 | 29 | 22.9 | 9.5 to 55.1 | <0.001 |

| Previous rejection episodea | |||||

| No | 796 | 53 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 205 | 24 | 1.9 | 1.2 to 3.2 | 0.005 |

| Proteinuria at 1 yr (log10 value) | 984 | 75 | 1.92 | 1.64 to 2.25 | <0.001 |

| Histologic parameters | |||||

| Atrophy scarring | |||||

| Low (≤1) | 862 | 59 | 1 | — | — |

| High (>1) | 117 | 16 | 2.2 | 1.4 to 3.5 | <0.001 |

| Arteriosclerosis | |||||

| Low (≤1) | 606 | 45 | 1 | — | — |

| High (>1) | 307 | 27 | 1.5 | 0.9 to 2.4 | 0.10 |

| Subclinical TCMR | |||||

| No | 869 | 67 | 1 | — | — |

| Yes | 132 | 10 | 0.8 | 0.4 to 1.6 | 0.62 |

| Subclinical ABMR | |||||

| No | 859 | 48 | 1 | — | — |

| Yes | 142 | 29 | 4.4 | 2.8 to 7.0 | <0.001 |

| C4db graft deposition | |||||

| No | 656 | 41 | 1 | — | — |

| Yes | 81 | 12 | 3.2 | 1.7 to 6.1 | <0.001 |

| Immunologic parameters | |||||

| DSA at 1 yr | |||||

| No | 745 | 41 | 1 | — | — |

| Yes | 256 | 36 | 3.25 | 2.1 to 5.1 | <0.001 |

eGFR was estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula.

Acute clinical biopsy-proven rejection occurring before the 1-year protocol biopsy diagnosis of rejection (n=205; 82 TCMR and 123 ABMR).

Circulating DSAs, microcirculation inflammation lesions, glomerulitis, and peritubular capillaritis are integrated in the Cox models as part of the definition of subclinical ABMR.

When considering significant risk factors in a single multivariate model, the following independent predictors of graft loss were identified: low eGFR (hazard ratio [HR], 11.4; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 4.5 to 28.6), intermediate eGFR (HR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.2 to 6.7; P<0.001), proteinuria at 1 year (log10 value; HR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3 to 1.8; P<0.001), and subclinical ABMR (HR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.8 to 4.9; P<0.001) (Table 3). Subclinical ABMR remained associated with an increased risk of graft loss in each category of eGFR (Figure 4B).

Table 3.

Multivariate associations of clinical, functional, histologic, and immunologic parameters with kidney graft loss

| Parameters | Number of Patients | Number of Events | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR at 1 yr, ml/min | |||||

| eGFR≥60 | 305 | 6 | 1 | — | — |

| 30≤eGFR<60 | 577 | 38 | 2.86 | 1.21 to 6.78 | — |

| eGFR<30 | 79 | 28 | 11.42 | 4.55 to 28.65 | <0.001 |

| Subclinical ABMR | |||||

| No | 825 | 45 | 1 | — | — |

| Yes | 136 | 27 | 2.99 | 1.81 to 4.96 | <0.001 |

| Proteinuria at 1 yr (log10 value) | 961 | 72 | 1.50 | 1.26 to 1.79 | <0.001 |

Final multivariate Cox model obtained by entering risk factors from the univariate model reaching P≤0.10 as the threshold in a single multivariate proportional hazards model. The final multivariate model is adjusted on the following parameters: (1) donor age, (2) donor type, (3) cold ischemia time, (4) graft rank, (5) delayed graft function, (6) atrophy scarring, and (7) C4d graft deposition. eGFR was estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula.

Sensitivity Analyses

After adjusting for acute rejection episodes occurring before the 1-year screening biopsy, the set of risk factors for graft loss identified in the single multivariate model remained unchanged, and subclinical ABMR at the 1-year protocol biopsy remained significantly associated with the risk of graft loss independent of previous immunologic events (TCMR and/or ABMR) (Supplemental Table 3).

Finally, we tested separately the association of subclinical ABMR with allograft loss in patients without acute rejection before the 1-year biopsy (n=796) and patients with acute rejection before the 1-year biopsy (n=205). We found that, in both groups, subclinical ABMR at 1 year post-transplant remained independently associated with the risk of allograft loss: HR, 6.8; 95% CI, 3.3 to 13.7 in patients without prior acute rejection (P<0.001) and HR, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.4 to 9.2 in those with prior acute rejection (P=0.007). Taken together, these results confirm that subclinical ABMR in 1-year screening biopsies carries a prognostic value, irrespective of previous immunologic events.

External Validation

The external validation cohort (n=321) characteristics are detailed in Supplemental Table 4. The graft survival according to rejection phenotype confirmed that patients with subclinical ABMR had the greatest risk of graft loss compared with patients with subclinical TCMR and patients without rejection (P<0.001) (Supplemental Figure 1). We also validated the multivariate model of the independent predictors of kidney allograft failure, showing that 1-year subclinical ABMR (HR, 5.7; 95% CI, 2.9 to 11.4; P<0.001) remained independently associated with graft failure (Supplemental Table 5). Finally, we reproduced the association of subclinical ABMR with increased risk of graft loss in each category of eGFR (Supplemental Figure 2).

Discussion

Using contemporary immunologic and histopathologic techniques together with an epidemiologic approach integrating the whole spectrum of allograft injury, we showed in a large prospective cohort of kidney transplants recipients that two distinct phenotypes of subclinical rejection (subclinical TCMR and subclinical ABMR) have distinct long-term outcomes. Subclinical ABMR is associated with increased GFR decline, development of transplant glomerulopathy, and higher risk of graft loss, whereas subclinical TCMR does not have a significant effect on long-term graft outcome. Importantly, we show that the 1-year screening biopsy for microcirculation injury carries an independent prognostic value that is independent of initial DSA status, previous immunologic events (TCMR or ABMR), and conventional laboratory testing for eGFR and proteinuria.

We found that, at 1 year post-transplant, 27% of patients presented with subclinical rejection that would not have called for the clinician’s attention on the basis of traditional monitoring of allograft function. We also found that patients with subclinical ABMR progressed to graft loss independent of the degree of graft scarring lesions and regardless of GFR or proteinuria at the time of biopsy, confirming the independence of subclinical ABMR from the concomitant assessment of kidney function and proteinuria. Finally, we show that subclinical ABMR impairs allograft outcome independently of the prior occurrence of rejection events. Therefore, subclinical ABMR represents either the onset of disease (de novo subclinical ABMR) or an ongoing disease (persisting humoral process) operating in a stable patient who has had a previous immunologic event. Importantly, the inclusion in this study of the overall history of biopsies for cause performed before 1 year makes it possible to show that, in the two situations encountered in the setting of subclinical ABMR (de novo versus persistent), the screening biopsy carries an independent prognostic value.

The finding of normal and stable allograft function, despite a biopsy showing lymphocytic infiltrates, has been observed since the 1980s. It has been further established that serum creatinine, the gold standard biomarker of renal injury, is very insensitive, particularly at GFRs ranging from 50 to 90 ml/min, which represent the most common situations encountered in kidney recipients at 1 year post-transplant. Therefore, the rationale for performing screening biopsies is to clarify the underlying state of renal integrity and determine subclinical abnormalities at an early stage that might be amenable to interventions with minimal risk of morbidity. The reported risk of major complications from protocol biopsy, including substantial bleeding, macroscopic hematuria with ureteric obstruction, peritonitis, and graft loss, is approximately 1%.21,22

The reported rates of subclinical rejection varied from 9% to 49% according to the immunologic profile and the immunosuppressive regimen used as well as the criteria and techniques used to diagnose it. Rush et al.9,10 reported in patients with low immunologic risk (excluding plasma renin activity>50% and previous graft loss to rejection) a prevalence of 9% at 6 months post-transplant, whereas Moreso et al.12 reported a prevalence of 14.2%–34.7% according to the immunosuppressive regimen used.8 Wiebe et al.23 reported a prevalence of 26% on the basis of 6-month protocol biopsies from patients with de novo DSAs. In this study, we found a prevalence of 48.9% at 3 months post-transplant in patients with preexisting/day 0 DSAs.

This study represents the whole spectrum of standard risk that can be encountered post-transplant in the era of the allocation system on the basis of complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) crossmatch assessment, which still remains the current gold standard approach worldwide. Other allocation policies on the basis of more sensitive techniques are local/national practices. Therefore, unlike other cohorts, there was no bias on the basis of immunologic risk in the selection of patients.

Our study also highlights the deleterious effect of preexisting DSAs. The allocation policies must minimize/avoid DSAs whenever possible. The Luminex and calculated panel reactive antibodies practices (July of 2009 in France and October of 2009 in the United States, respectively) have allowed the allocation of kidneys against which kidney recipients have preformed anti-HLA antibodies to be limited and theoretically, may have had an effect on decreasing the risk of ABMR and subclinical ABMR. Nevertheless, there remain approximately 15%–35% (United Nation for Organ Sharing and French National Agency for Organ Procurement) of waitlisted candidates for kidney transplants who are highly sensitized and therefore, do not have a sufficient flow of potential matched donors, and these candidates have to receive transplants through HLA-incompatible programs. This study showed that these patients require specific clinical, immunologic, and histologic monitoring and in particular, an early and accurate recognition of subclinical ABMR.

In our cohort, we found that 22% of patients with subclinical ABMR were associated with de novo DSA, confirming that, beyond the deleterious effect of recurrent DSA, de novo DSA may be harmful and occur in clinically stable patients.23

Another important result was the lack of association of subclinical TCMR with allograft survival, thus challenging the historical conclusion from registry studies that TCMR increases the risk of future graft loss. This result confirms the findings of recent clinical trials showing that indolent TCMR can be adequately treated and is not associated per se with graft loss in adherent patients.10,24 However, late TCMR could be a warning sign of nonadherence, which can have a devastating effect on kidney allograft survival, often precipitating ABMR.5 In our study, all patients with subclinical TCMR received steroid pulse-based therapy, suggesting that early screening and adapted therapy may be beneficial over the long term. We were also able to show in this study that a subset of patients with 1-year subclinical TCMR may further develop de novo DSA and progress to TG, and this development deserves specific study.

Our study shows the early detection of indolent histologic changes related to ABMR, a condition that more transplant clinicians will have to face because of the growing number of waitlisted sensitized patients worldwide who will likely be receiving incompatible kidney allografts and also, because of the growing concern regarding de novo DSA.25–27 Finally, a precise screening and phenotyping strategy for these patients during the early stages post-transplant may call into question more aggressive management with potent antibody-targeting strategies, such as those involving intravenous Ig, plasmaphereses, anti-CD20, Bortezomib, and therapeutic agents targeting complement (e.g., anti-C5 [eculizumab] or -C1 inhibitors).28,29 The therapeutic decision in our cohort was made by the attending team of physicians according to the knowledge of subclinical ABMR that we had at the time of diagnosis. In light of the experience that we now have with subclinical ABMR and its detrimental effect on allograft outcome, we have changed our practice, and we are now treating these patients with antibody-targeting agents. There is currently a randomized study underway to answer to the specific question regarding the best therapeutic approach in subclinical ABMR: the TAMARCIN (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02113891).

The main limitation of the study was that we did not identify the best therapeutic approach for subclinical ABMR. The retrospective nature of our study and the 10-year inclusion period led us to describe (at a population scale) the natural history of subclinical ABMR but did not reflect the efficacy of therapy. Our study design did not allow us to make a standardized therapeutic decision for patients experiencing subclinical ABMR at 1 year post-transplant. This is the case in any ABMR study, and randomized studies are still needed. Although our study did not address this specific question, it provided the basis for future interventional studies regarding the treatment of subclinical ABMR. In addition, the purpose of this study was not to address the issue of the optimal time for screening biopsy. We designed this study to test the hypothesis that an early diagnosis of subclinical ABMR contributes to improve the risk assessement of kidney allograft loss. The time point that we chose to use in this study (1 year post-transplant) is the time point with the maximum likelihood of an immunologic event, and it is widely used in the transplant literature as a relevant time point for modeling the determinants of kidney allograft loss. We followed the updated criteria from the last Banff conference for the diagnosis of subclinical ABMR, but these criteria do not cover some cases of microcirculation inflammation without C4d deposition and without detectable DSAs at the time of biopsy. This entity is seldom observed (n=8) but deserves specific studies.

Lastly, an important question is whether the kidney transplant community should now plan to schedule routine protocol biopsies to detect subclinical ABMR (de novo or persisting process). Our data show that this may be important for patients with baseline DSAs, even if DSA levels are weak, stable patients in whom a de novo DSA is detected, and any patient who has experienced previous immunologic events (ABMR and/or TCMR). Nevertheless, the individual cost/risk benefit of this approach for stable transplant recipients with completely negative baseline DSAs and no for-cause biopsies remains to be determined.

On the basis of a population-based study using contemporary tools for allograft phenotyping, we reported the outcomes of subclinical rejection of kidney allografts. We found that subclinical ABMR encountered in patients with either de novo DSAs or preexisting/persisting DSAs is a strong factor associated with long-term allograft function deterioration and kidney allograft loss that is independent of conventional laboratory testing for monitoring allograft function and proteinuria.

In the modern immunosuppressive era with precise screening and treatment, subclinical TCMR is not associated with significant effect on allograft outcome but triggers the appearance of de novo DSAs and progression to TG in a subset of patients.

Finally, the recognition of subclinical ABMR could guide clinicians in identifying patients at risk for failure and providing a basis for early and adapted therapeutic interventions.

Concise Methods

Participants

This population-based study enrolled consecutive and nonselected patients (n=1307) who underwent kidney transplantation across a negative CDC crossmatch at Necker Hospital between January 1, 2000, and January 1, 2010. We included all clinically stable patients who underwent adequate protocol allograft biopsies performed at 1 year post-transplant.

We used an additional independent validation sample of 321 kidney recipients from Saint Louis Hospital (Supplemental Material). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Necker Hospital and Saint Louis Hospital. All of the transplantations were ABO blood group-compatible. Negative current IgG T cell and B cell CDC crossmatching was required for all of the recipients. No patient received preconditioning desensitization treatment before transplantation. We excluded patients who did not reach the 1-year follow-up for the following reasons—graft failure (n=44), death (n=27), or loss to follow-up (n=38)—as well as patients in whom a screening biopsy was not performed (contraindication/refusal [n=98] or suffered a rejection episode in 21 days before the 1-year biopsy [n=16]) or the screening biopsy was performed but not adequate according to the Banff classification requirements (n=83).30 The baseline characteristics of the kidney allograft recipients with and without available protocol biopsies are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Definition and Treatment of Subclinical Rejection Patterns

In this study, we considered all 1-year screening biopsies performed in patients receiving kidney transplants over a 10-year period. Protocol biopsies were performed in grafts associated with stable renal function, which was defined as variability in serum creatinine not exceeding 15% of baseline values within a period of 21 days before the biopsy. All of the graft biopsies were scored and graded by trained pathologists (J.-P.D.v.H., M.R., J.V., and D.N.) according to the updated Banff criteria8,30 (Supplemental Material).

Subclinical TCMR was defined by stable renal function in addition to the following histologic features: presence of significant interstitial infiltration (>25% of parenchyma affected [i2 or i3]) and foci of moderate tubulitis (t2) or significant interstitial infiltration (>25% of parenchyma affected [i2 or i3]) and foci of severe tubulitis (t3).

Subclinical ABMR was defined by stable renal function in addition to the following histologic features: histologic evidence of intravascular inflammation (capillaritis and/or glomerulitis lesions) and serologic evidence of circulating DSAs. We acknowledged patients with intravascular inflammation and circulating DSAs without evidence of C4d complement deposition as having C4d-negative subclinical ABMR according to the updated Banff 2013 classification.31 We examined all patient biopsies associated with a diagnosis of rejection (n=205; 82 TCMR and 123 ABMR) occurring before the 1-year protocol biopsy. We also assessed 317 for-cause biopsies performed after 1 year post-transplant.

Data on post-transplant maintenance immunosuppression therapy and the treatment of rejection episodes are available in Supplemental Material.

C4d staining was performed by immunohistochemistry on paraffin sections using the human C4d polyclonal antibody (Biomedica Gruppe). C4d staining was graded from 0 to 3 on the basis of the percentage of peritubular capillaries with linear staining, and grades 2 and 3 were considered to be positive.

Clinical Data

The clinical data for donors and recipients in the development (Necker Hospital) and the validation (Saint Louis Hospital) cohorts were obtained from two national registries, Données Informatiques Validées en Transplantation (Necker Hospital) and Agence de la Biomédecine (Saint Louis Hospital), in which data are prospectively entered at specific time points for each patient (day 0, 6 months, and 1 year post-transplant) and follow-up data are entered annually thereafter32,33 (Supplemental Material). The data from the development cohort were retrieved from the database on April 15, 2012, whereas the data from the validation cohort were retrieved on December 19, 2012.

Definition of Outcomes

The outcomes measured in this study were graft loss defined by a return to dialysis and course of kidney allograft function over time defined by eGFR measurements34 at 3 months post-transplant, the time of the 1-year protocol biopsy, and every year thereafter, with a mean total of 4.511 longitudinal eGFRs studied.

Detection of Antibodies against Donor-Specific HLA Molecules

We retrospectively determined the presence of circulating HLA-A/B/C/DR/DQ/DP DSAs at 1 year post-transplant in all patients with available sera (142 of 142 patients with subclinical ABMR, 132 of 132 patients with subclinical TCMR, and 532 of 737 patients without rejection). In addition, patients with a subclinical rejection phenotype were also assessed for day 0 circulating DSAs. For this analysis, we used single-antigen flow bead assays (One Lambda, Inc., Canoga Park, CA) on a Luminex platform (Supplemental Material).

Statistical Analyses

We provide means and SDs for the descriptions of continuous variables, with the exception of MFI, for which we use means and SEMs because of its wide distribution. We compared means and proportions with t tests and chi-squared tests (or Fisher exact tests if appropriate). We used ANOVA to compare the histologic Banff scores between patient groups.

The associations between 1-year screening biopsy phenotypes and graft function during follow-up were analyzed using linear mixed models.36 For the follow-up biopsy analysis, we calculated conditional density plots using the R package cdplot. Probabilities are derived by applying a smoothing filter to the R density function and integrating the time of biopsy.

The associations between rejection phenotypes at 1 year post-transplant and the course of eGFR during follow-up were analyzed with linear mixed models. Mixed models use all available data during follow-up, properly account for correlation between repeated measurements, appropriately handle data missing at random, and allow for the use of time-independent and -dependent covariates. In this analysis, we included 4.511 longitudinal eGFRs assessed over 8 years post-transplant. To minimize bias caused by data missing because of graft loss or loss to follow-up, we assigned 1-year eGFR values of 10 ml/min in the case of graft loss and carried forward the last known eGFR value in the case of patient death with function or loss to follow-up.

The survival analysis was performed for a maximum follow-up period of 8 years from the time of transplantation, with kidney graft loss as the event of interest defined by return to dialysis or preemptive retransplantation. For patients who died with a functioning graft (n=73; 7%), graft survival was censored at the time of death.37 Kidney allograft survival over time, according to graft rejection phenotype, was plotted on Kaplan–Meier curves and compared using the log-rank test. Within each group of potential risk factors, including clinical, histologic, functional, and immunologic parameters, we performed univariate analysis. Then, selected risk factors (using P≤0.10 as the threshold) were entered into a single multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to identify independent predictive factors of kidney graft loss.

The analyses were conducted using SAS (Statistical Analysis System, Cary, NC) software, version 9.2 and R software (version 2.10.1). All of the tests were two-sided, and P values<0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Begin at the Beginning to Prevent the End,” on pages 1483–1485.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2014040399/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients : Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients 2010 data report. Am J Transplant 12 [Suppl 1]: 1–156, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapport 2011 de l'activité de prélèvement et de greffe de l'Agence de la Biomédecine. Available at: http://www.agence-biomedecine.fr/Rapport-annuel-2011. Accessed January 20, 2013

- 3.Nankivell BJ, Kuypers DR: Diagnosis and prevention of chronic kidney allograft loss. Lancet 378: 1428–1437, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaston RS, Cecka JM, Kasiske BL, Fieberg AM, Leduc R, Cosio FC, Gourishankar S, Grande J, Halloran P, Hunsicker L, Mannon R, Rush D, Matas AJ: Evidence for antibody-mediated injury as a major determinant of late kidney allograft failure. Transplantation 90: 68–74, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sellarés J, de Freitas DG, Mengel M, Reeve J, Einecke G, Sis B, Hidalgo LG, Famulski K, Matas A, Halloran PF: Understanding the causes of kidney transplant failure: The dominant role of antibody-mediated rejection and nonadherence. Am J Transplant 12: 388–399, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Racusen LC, Colvin RB, Solez K, Mihatsch MJ, Halloran PF, Campbell PM, Cecka MJ, Cosyns JP, Demetris AJ, Fishbein MC, Fogo A, Furness P, Gibson IW, Glotz D, Hayry P, Hunsickern L, Kashgarian M, Kerman R, Magil AJ, Montgomery R, Morozumi K, Nickeleit V, Randhawa P, Regele H, Seron D, Seshan S, Sund S, Trpkov K: Antibody-mediated rejection criteria - an addition to the Banff 97 classification of renal allograft rejection. Am J Transplant 3: 708–714, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solez K, Colvin RB, Racusen LC, Sis B, Halloran PF, Birk PE, Campbell PM, Cascalho M, Collins AB, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Gibson IW, Grimm PC, Haas M, Lerut E, Liapis H, Mannon RB, Marcus PB, Mengel M, Mihatsch MJ, Nankivell BJ, Nickeleit V, Papadimitriou JC, Platt JL, Randhawa P, Roberts I, Salinas-Madriga L, Salomon DR, Seron D, Sheaff M, Weening JJ: Banff ‘05 Meeting Report: Differential diagnosis of chronic allograft injury and elimination of chronic allograft nephropathy (‘CAN’). Am J Transplant 7: 518–526, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mengel M, Sis B, Haas M, Colvin RB, Halloran PF, Racusen LC, Solez K, Cendales L, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Farver CF, Rodriguez ER, Wallace WD, Glotz D, Banff meeting report writing committee : Banff 2011 Meeting report: New concepts in antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant 12: 563–570, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rush DN, Henry SF, Jeffery JR, Schroeder TJ, Gough J: Histological findings in early routine biopsies of stable renal allograft recipients. Transplantation 57: 208–211, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rush D, Nickerson P, Gough J, McKenna R, Grimm P, Cheang M, Trpkov K, Solez K, Jeffery J: Beneficial effects of treatment of early subclinical rejection: A randomized study. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2129–2134, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CL, O’Connell PJ, Allen RD, Chapman JR: The natural history of chronic allograft nephropathy. N Engl J Med 349: 2326–2333, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreso F, Ibernon M, Gomà M, Carrera M, Fulladosa X, Hueso M, Gil-Vernet S, Cruzado JM, Torras J, Grinyó JM, Serón D: Subclinical rejection associated with chronic allograft nephropathy in protocol biopsies as a risk factor for late graft loss. Am J Transplant 6: 747–752, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loupy A, Suberbielle-Boissel C, Hill GS, Lefaucheur C, Anglicheau D, Zuber J, Martinez F, Thervet E, Méjean A, Charron D, Duong van Huyen JP, Bruneval P, Legendre C, Nochy D: Outcome of subclinical antibody-mediated rejection in kidney transplant recipients with preformed donor-specific antibodies. Am J Transplant 9: 2561–2570, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bentall A, Cornell LD, Gloor JM, Park WD, Gandhi MJ, Winters JL, Chedid MF, Dean PG, Stegall MD: Five-year outcomes in living donor kidney transplants with a positive crossmatch. Am J Transplant 13: 76–85, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu GW, Kobashigawa JA, Fishbein MC, Patel JK, Kittleson MM, Reed EF, Kiyosaki KK, Ardehali A: Asymptomatic antibody-mediated rejection after heart transplantation predicts poor outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant 28: 417–422, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kfoury AG, Hammond ME, Snow GL, Drakos SG, Stehlik J, Fisher PW, Reid BB, Everitt MD, Bader FM, Renlund DG: Cardiovascular mortality among heart transplant recipients with asymptomatic antibody-mediated or stable mixed cellular and antibody-mediated rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant 28: 781–784, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tippner C, Nashan B, Hoshino K, Schmidt-Sandte E, Akimaru K, Böker KH, Schlitt HJ: Clinical and subclinical acute rejection early after liver transplantation: Contributing factors and relevance for the long-term course. Transplantation 72: 1122–1128, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartlett AS, Ramadas R, Furness S, Gane E, McCall JL: The natural history of acute histologic rejection without biochemical graft dysfunction in orthotopic liver transplantation: A systematic review. Liver Transpl 8: 1147–1153, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haas M, Montgomery RA, Segev DL, Rahman MH, Racusen LC, Bagnasco SM, Simpkins CE, Warren DS, Lepley D, Zachary AA, Kraus ES: Subclinical acute antibody-mediated rejection in positive crossmatch renal allografts. Am J Transplant 7: 576–585, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papadimitriou JC, Drachenberg CB, Ramos E, Kukuruga D, Klassen DK, Ugarte R, Nogueira J, Cangro C, Weir MR, Haririan A: Antibody-mediated allograft rejection: Morphologic spectrum and serologic correlations in surveillance and for cause biopsies. Transplantation 95: 128–136, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furness PN, Philpott CM, Chorbadjian MT, Nicholson ML, Bosmans JL, Corthouts BL, Bogers JJ, Schwarz A, Gwinner W, Haller H, Mengel M, Seron D, Moreso F, Cañas C: Protocol biopsy of the stable renal transplant: A multicenter study of methods and complication rates. Transplantation 76: 969–973, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fereira LC, Karras A, Martinez F, Thervet E, Legendre C: Complications of protocol renal biopsy. Transplantation 77: 1475–1476, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiebe C, Gibson IW, Blydt-Hansen TD, Karpinski M, Ho J, Storsley LJ, Goldberg A, Birk PE, Rush DN, Nickerson PW: Evolution and clinical pathologic correlations of de novo donor-specific HLA antibody post kidney transplant. Am J Transplant 12: 1157–1167, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurtkoti J, Sakhuja V, Sud K, Minz M, Nada R, Kohli HS, Gupta KL, Joshi K, Jha V: The utility of 1- and 3-month protocol biopsies on renal allograft function: A randomized controlled study. Am J Transplant 8: 317–323, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery RA, Lonze BE, King KE, Kraus ES, Kucirka LM, Locke JE, Warren DS, Simpkins CE, Dagher NN, Singer AL, Zachary AA, Segev DL: Desensitization in HLA-incompatible kidney recipients and survival. N Engl J Med 365: 318–326, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solez K, Colvin RB, Racusen LC, Haas M, Sis B, Mengel M, Halloran PF, Baldwin W, Banfi G, Collins AB, Cosio F, David DS, Drachenberg C, Einecke G, Fogo AB, Gibson IW, Glotz D, Iskandar SS, Kraus E, Lerut E, Mannon RB, Mihatsch M, Nankivell BJ, Nickeleit V, Papadimitriou JC, Randhawa P, Regele H, Renaudin K, Roberts I, Seron D, Smith RN, Valente M: Banff 07 classification of renal allograft pathology: Updates and future directions. Am J Transplant 8: 753–760, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lefaucheur C, Nochy D, Andrade J, Verine J, Gautreau C, Charron D, Hill GS, Glotz D, Suberbielle-Boissel C: Comparison of combination Plasmapheresis/IVIg/anti-CD20 versus high-dose IVIg in the treatment of antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant 9: 1099–1107, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loupy A, Suberbielle-Boissel C, Zuber J, Anglicheau D, Timsit MO, Martinez F, Thervet E, Bruneval P, Charron D, Hill GS, Nochy D, Legendre C: Combined posttransplant prophylactic IVIg/anti-CD 20/plasmapheresis in kidney recipients with preformed donor-specific antibodies: A pilot study. Transplantation 89: 1403–1410, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stegall MD, Diwan T, Raghavaiah S, Cornell LD, Burns J, Dean PG, Cosio FG, Gandhi MJ, Kremers W, Gloor JM: Terminal complement inhibition decreases antibody-mediated rejection in sensitized renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 11: 2405–2413, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB, Bonsib SM, Castro MC, Cavallo T, Croker BP, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Fogo AB, Furness P, Gaber LW, Gibson IW, Glotz D, Goldberg JC, Grande J, Halloran PF, Hansen HE, Hartley B, Hayry PJ, Hill CM, Hoffman EO, Hunsicker LG, Lindblad AS, Yamaguchi Y: The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney Int 55: 713–723, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haas M, Sis B, Racusen LC, Solez K, Glotz D, Colvin RB, Castro MC, David DS, David-Neto E, Bagnasco SM, Cendales LC, Cornell LD, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Farver CF, Farris AB, 3rd, Gibson IW, Kraus E, Liapis H, Loupy A, Nickeleit V, Randhawa P, Rodriguez ER, Rush D, Smith RN, Tan CD, Wallace WD, Mengel M, Banff meeting report writing committee : Banff 2013 meeting report: Inclusion of c4d-negative antibody-mediated rejection and antibody-associated arterial lesions. Am J Transplant 14: 272–283, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agence Biomédecine : Cristal. Available at: http://www.sipg.sante.fr/portail/. Accessed February 3, 2014

- 33.Donnée Informatiques VAlidées en Transplantation (DIVAT) : Donnée Informatiques VAlidées en Transplantation (DIVAT) software. Available at: http://www.divat.fr/. Accessed March 7, 2014

- 34.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group : A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med 130: 461–470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lefaucheur C, Loupy A, Hill GS, Andrade J, Nochy D, Antoine C, Gautreau C, Charron D, Glotz D, Suberbielle-Boissel C: Preexisting donor-specific HLA antibodies predict outcome in kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1398–1406, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West BT, Welch KB, Galecki AT: Linear Mixed Models: A Practical Guide to Using Statistical Software, New York, Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamb KE, Lodhi S, Meier-Kriesche HU: Long-term renal allograft survival in the United States: A critical reappraisal. Am J Transplant 11: 450–462, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.