Abstract

Objective: The management of cholangiocarcinoma remains a challenge due to poor prognosis. The aim of this study was to identify the influencing factors related to outcome of patients with cholangiocarcinoma. Methods: From January 1999 to January 2009, 169 cases of cholangiocarcinoma undergoing surgery were analyzed retrospectively. Relationships between survival and clinicopathological factors including patient demographics and tumor characteristics were evaluated using univariate and multivariate analysis. Results: The 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates of patients after resection were 52.6%, 32.4%, 11.7%, respectively. Univariate analysis showed that CEA, lymph node metastasis, surgical margin, AJCC staging, tumor differentiation and adjuvant chemotherapy were prognostic impacts. The difference was statistically significant (P<0.05). Cox multivariate analysis showed that CEA, lymph node metastasis and surgical margin are three independent prognostic factors. Conclusion: Radical resection is the key to improve the long-term survival rate of cholangiocarcinoma. Important predictive factors related to poor survival are CEA, lymph node metastasis and surgical margin.

Keywords: Cholangiocarcinoma, survival, prognosis

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma is a rare malignant tumor of the biliary system with a poor prognosis. It is a second most common malignancy of primary liver tumors worldwide [1]. Cholangiocarcinoma is commonly classified into 3 groups based on the location of the tumor: intrahepatic, hilar and distal types. Surgical resection offers the only potential chance of cure in cholangiocarcinoma. The present study retrospectively analyzed 169 patients of cholangiocarcinoma, from January 1999 to January 2009 in the centre of Liaoning tumor hospital, Shen Zhou hospital, Huaxi hospital and the first hospital of China Medical University. The aim of this retrospective study was to indentify useful prognostic factors for patients with cholangiocarcinoma.

Patients

A total of 169 patients with cholangiocarcinoma underwent surgical therapy. The diagnosis was confirmed by histopathologic assessment (44 with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, 42 with hilar cholangiocarcinoma, and 83 with distal cholangiocarcinoma).

Patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma typically underwent pancreatoduodenectomy with or without pylorus preservation, while surgical procedures for patients with intrahepatic or hilar cholangiocarcinoma almost always included major hepatectomy. All patients underwent dissection of regional lymph nodes including the nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament, the anterior and posterior pancreatoduodenal nodes, and the nodes along the common hepatic artery. In addition to dissection of these lymph nodes, patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma underwent dissection of the nodes along the superior mesenteric artery while they underwent pancreatoduodenectomy. However, dissection of para-aortic lymph nodes was not routinely performed in all patients. Intraoperative pathological assessment of proximal or distal ductal margins was performed using frozen tissue sections. If the ductal margin was positive for cancerous cells, further resection of the bile duct was performed to the maximum extent possible.

Data for these patients were extracted from the hospital database and interviews, including gender, age, CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) levels, total bilirubin, BMI (body mass index), adjuvant chemotherapy, tumor location, tumor differentiation, AJCC staging (7th edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer), pT stage (pathological tumor), pN stage (pathological node),surgical margin, lymph node metastasis.

Statistical analysis

Death occurring within 30 days after the surgical procedure was defined as operative mortality. Death occurring after surgery and before discharge was defined as hospital mortality. Survival time was calculated from the date of surgery to death or censored date. Patients who died of cholangiocarcinoma were treated as event observations, and patients who died of unrelated causes and were alive at the last follow-up were treated as censored observations. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Significant prognostic factors in the univariate analysis were entered into the Cox proportional hazards multiple regression model, and stepwise selection of independent prognostic variables was performed manually by significant changes in likelihood ratio. A software program (SPSS 14.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

Patient demographics

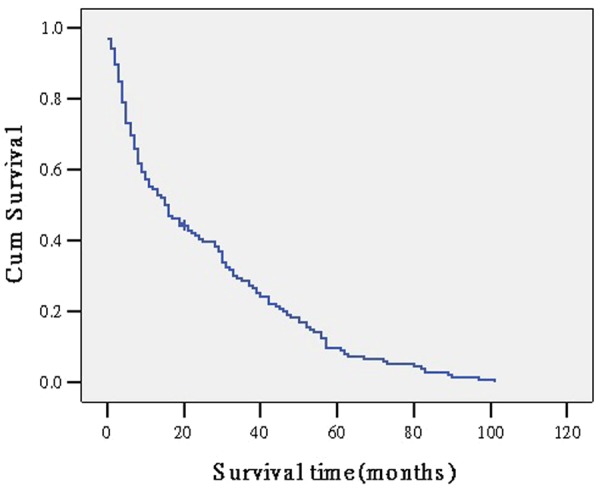

The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rate were 52.6%, 32.4%, 11.7%, respectively. The overall survival curve is showed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

the overall survival curve of all patients.

The study population included 98 men (57.9%) and 71 women (42.1%). The median age of all patients was 55 years (range, 33-84 years). 92 (54.4%) patients were more than 60 years old. 52 (30.8%) patients were administrated adjuvant chemotherapy. Pathologically, tumors were identified as well-differentiated adenocarcinoma in 71 patients (42.0%), moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma in 48 patients (28.4%), and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in 50 patients (12.4%). There were 73 cases (43.2%) with lymph node metastasis and 127 patients (75.1%) with negative surgical margins.

Six patients died in the hospital. These patients were excluded from further analyses. Furthermore, 25 patients with an uneventful perioperative course were excluded from analysis because they were lost to follow-up. Thus, data of 138 patients were eligible for final analyses.

Univariate analysis of outcome

We analyzed the effects 14 clinicopathologic factors on survival. CEA level (P<0.01), tumor differentiation (P<0.01), surgical margin (P=0.01), lymph node metastasis (P=0.02), adjuvant chemotherapy (P=0.04) and AJCC staging (P<0.01) showed significant prognostic value for survival (Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors

| Variable | No. of Patients | Median survival (month) | X2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 85 | 22.3 | ||

| Female | 53 | 23.5 | 0.61 | 0.46 |

| Age | ||||

| <60 | 59 | 22.1 | ||

| ≥60 | 79 | 22.9 | 2.14 | 0.19 |

| Surgical margin | ||||

| Negative | 113 | 27.6 | ||

| Positive | 25 | 19.3 | 4.31 | 0.01 |

| lymph node meatstasis | ||||

| Negative | 72 | 26.8 | ||

| Positive | 66 | 13.2 | 4.157 | 0.02 |

| Operative procedure | ||||

| Radical | 112 | 24.7 | ||

| Palliative | 26 | 20.5 | 3.57 | 0.06 |

| Location of tumor | ||||

| Intrahepatic | 36 | 27.4 | ||

| Hilar | 38 | 19.2 | ||

| Distal | 64 | 23.5 | 4.29 | 0.05 |

| CA 19-9 level | ||||

| <37 ku/ml | 57 | 24.1 | ||

| ≥37 ku/m l | 81 | 23.8 | 1.634 | 0.39 |

| CEA level | ||||

| <15 ng/ml | 68 | 28.2 | ||

| ≥15 ng/ml | 70 | 19.7 | 10.24 | <0.01 |

| Tumor differentiation | ||||

| Well | 68 | 26.7 | ||

| Moderate | 32 | 25.1 | ||

| poorly | 38 | 20.1 | 22.54 | <0.01 |

| Total bilirubin | ||||

| <17.1 umol/l | 49 | 31.2 | ||

| ≥17.1 umol/l | 89 | 24.6 | 3.48 | 0.06 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 46 | 33.4 | ||

| No | 92 | 26.0 | 3.97 | 0.04 |

| AJCC staging | ||||

| 0 | 6 | 33.5 | ||

| 1 | 21 | 31.2 | ||

| 2 | 30 | 22.4 | ||

| 3 | 46 | 21.1 | ||

| 4 | 35 | 15.6 | 9.64 | <0.01 |

| pT stage | ||||

| 0 | 5 | 34.4 | ||

| 1 | 24 | 29.3 | ||

| 2 | 42 | 24.5 | ||

| 3 | 48 | 20.8 | ||

| 4 | 19 | 16.7 | 4.69 | 0.02 |

| pN stage | ||||

| 0 | 87 | 29.5 | ||

| 1 | 51 | 24.1 | 5.23 | 0.01 |

Multivariate analysis of outcome

The prognostic factors in the univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate model to identify independent predictors of long-term survival. Among the six significant variables, surgical margin, lymph node metastasis and CEA level were identified as independent prognostic factors. AJCC staging was not used as a dependent variable in the multivariate survival analysis to avoid confounding with nodal status.

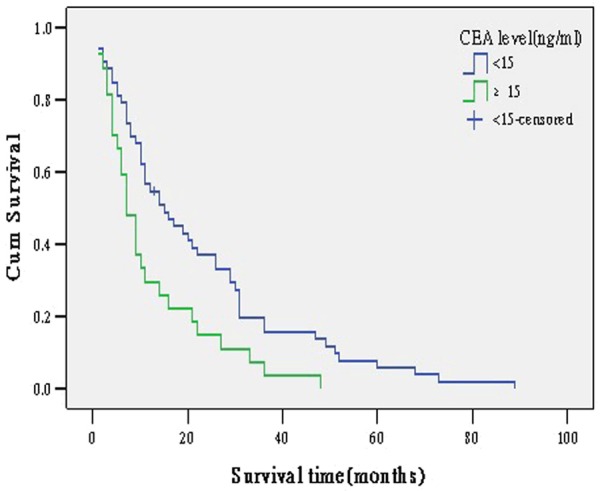

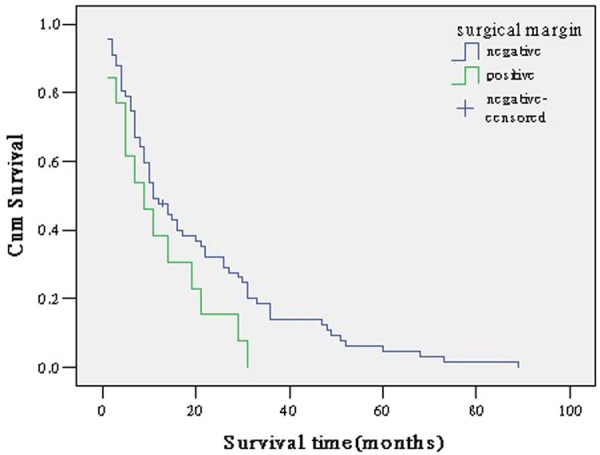

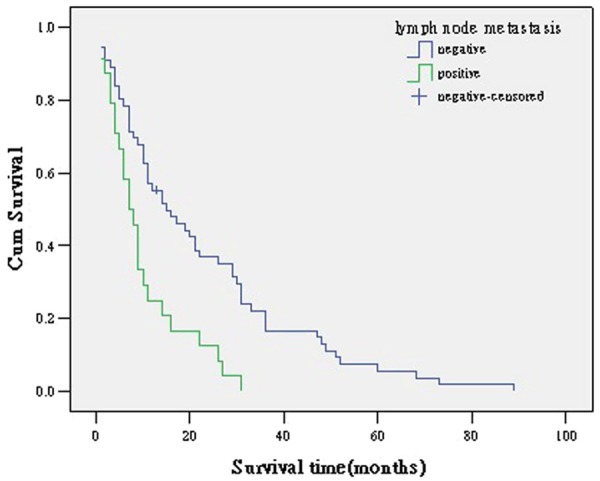

Of these, CEA level were clearly the most influential, with an increase in the likelihood of death of 2.134 times if preoperative CEA level greater than 15 ng/mL, followed by lymph node metastasis (relative risk, 1.943), and surgical margin as a favorable factor (relative risk, 0.619) (Table 2; Figures 2, 3 and 4).

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis prognostic factors

| Variable | β | Wald c2 | P value | Relative Risk (RR) | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Surgical margin | -1.865 | 8.763 | 0.001 | 0.619 | 0.451 | 0.850 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.693 | 6.871 | 0.012 | 1.943 | 1.182 | 3.193 |

| CEA level | 0.752 | 10.259 | 0.006 | 2.134 | 1.342 | 3.393 |

Figure 2.

survival curve according to CEA level.

Figure 3.

survival curve according to lymph node metastasis.

Figure 4.

survival curve according to surgical margin.

Discussion

Cholangiocarcinoma is considered to be an incurable and rapidly lethal malignancy unless both the primary tumor and any metastases can be fully resected (removed surgically). Recent decades, we have achieved significant advancements in surgical training, hepatobiliary techniques, anesthetic management, and overall critical care, which have increased the number of patients suitable for surgery and the safety of the procedure. However, the prognosis for patients with cholangiocarcinoma is still poor. So understanding the prognostic factors of patients is extremely important. This study indentified three independent prognostic variables that were significantly correlated with survival.

Surgical margin status is a prognostic factor in several cancers, including cholangiocarcinoma. Median survivals of patients who had negative resection margin (R0) were markedly longer than those who had macroscopic positive margin (R2) and microscopic positive margin (R1). Our study found surgical margin status was an independent prognostic factor by multivariate analysis. Patients with positive surgical margin had a 2.134 times (95% CI: 1.342-3.393) higher mortality risk than those with negative margin. Many other countries studies have also shown that surgical margin status is one of the most potent prognostic factors in cholangiocarcinoma [2-6]. Based on these results, curative resection is mandatory for long-term survival in cholangiocarcinoma. The most frequent causes of non-resectability are liver and distant metastases, peritoneal carcinomatosis, infiltration of the vessels at the hepatic hilum, and the infiltration of adjacent organs or structures.

Recent researches have reported rates for lymph node metastasis of 27-47% for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, 24-47% for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, and 25-63% for distal cholangiocarcinoma [7-15]. In our study, survival was compromised by the presence of lymph node metastasis as demonstrated by both univariate and multivariate analysis, with an increase in the likelihood of mortality risk of 1.943 times. Some previous reports also got the same conclusion [16-20]. Patients without lymph node metastasis undergoing R0 resection had a longer median survival than those with lymph node metastasis undergoing R0 resection. Though lymph node metastasis was associated with poor prognosis, routine regional lymphadenectomy for patients without evidence of lymph node involvement remains controversial [21-23]. However, five patients with nodal involvement have survived for more than 5 years in our series. We believe that the performance of lymph node dissection during our resections contributed to locoregional control and as a result there were five 5-year survivors with nodal involvement in our series.

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a glycoprotein involved in cell adhesion. It is usually present only at very low levels in the blood of healthy adults. However, the serum levels are raised in some types of cancer. Some previous studies demonstrated that cancer patients with a high level of serum CEA were associated with poor prognosis [24,25]. This multivariate analysis confirmed that the level of serum CEA above 15 ng/ml was an independent poor prognostic factor and patients with level of serum CEA above 15 ng/ml had a 2.22 times (95% CI: 1.11-2.33) higher mortality risk than those with lower serum level of CEA, which is similar to previous studies [26].

Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation is a controversial issue in cholangiocarcinoma. Our study did not show any impact of adjuvant chemotherapy, maybe because of the small number of treated patients. Takada et al. [27] compared therapy with mitomycin C and 5-FU to surgery alone in a randomized controlled trial of patients who underwent radical resection of cholangiocarcinoma. They reported that the 5-year survival rates for patients with hilar or distal cholangiocarcinoma did not differ based on postoperative chemotherapy or surgery alone. But many previous retrospective studies showed benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy [28,29]. Gerhards et al. [30] reported that in 91 patients who underwent surgical resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma, overall median survival was significantly longer in patients treated with adjuvant radiotherapy than in those who underwent resection alone. Hughes et al. [31] reported that 68 patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma found that patients who underwent surgery and received chemoradiation had significantly longer actuarial mean survival compared with those who underwent surgery alone. Furthermore, a meta-analysis showed that chemotherapy as a part of adjuvant therapy which included radiotherapy and concurrent chemoradiotherapy may be beneficial in resectable cholangiocarcinoma patients with high risk features, such as lymph node metastases and positive surgical margins [32]. Some new anticancer drugs including gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, capecitabine, and S-1 have been reported recently to have favorable anticancer effects on patients with unresectable biliary tract carcinoma [33-35]. So randomized controlled trials should be conducted to define the roleof postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

In conclusion, factors such CEA, lymph node metastasis and surgical margin were statistical significantly associated with the survival time of cholangiocarcinoma patients. However, the limitations of this study are retrospective design ad the relatively small number of patients studied. Prospective studies enrolling a larger number of patients are required to confirm the results of this study.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Olnes MJ, Erlich R. A review and update on cholangiocarcinoma. Oncology. 2004;66:167–179. doi: 10.1159/000077991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uenishi T, Kubo S, Yamazaki O, Yamada T, Sasaki Y, Nagano H, Monden M. Indications for surgical treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with lymph node metastases. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:417–22. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee SG, Song GW, Hwang S, Ha TY, Moon DB, Jung DH, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Sung KB, Ko GY. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in the new era: the Asian experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:476–89. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unno M, Katayose Y, Rikiyama T, Yoshida H, Yamamoto K, Morikawa T, Hayashi H, Motoi F, Egawa S. Major hepatectomy for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:463–9. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Ohge H, Sueda T. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and surgical margin status for distal cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:207–12. doi: 10.1002/jso.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Kamangar F, Winter JM, Lillemoe KD, Choti MA, Yeo CJ, Schulick RD. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty-oneyear experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2007;245:755–62. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251366.62632.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Campagnaro T, Pachera S, Valdegamberi A, Nicoli P, Cappellani A, Malfermoni G, Iacono C. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: prognostic factors after surgical resection. World J Surg. 2009;33:1247–54. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hayashidani Y, Hashimoto Y, Nakamura H, Nakashima A, Sueda T. Gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival after aggressive surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1470–9. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0900-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Igami T, Nishio H, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Sugawara G, Nimura Y, Nagino M. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in the “new era”: the Nagoya University experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:449–54. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirano S, Kondo S, Tanaka E, Shichinohe T, Tsuchikawa T, Kato K, Matsumoto J, Kawasaki R. Outcome of surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a special reference to postoperative morbidity and mortality. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:455–62. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SG, Song GW, Hwang S, Ha TY, Moon DB, Jung DH, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Sung KB, Ko GY. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in the new era: the Asian experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:476–89. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unno M, Katayose Y, Rikiyama T, Yoshida H, Yamamoto K, Morikawa T, Hayashi H, Motoi F, Egawa S. Major hepatectomy for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:463–9. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Ohge H, Sueda T. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and surgical margin status for distal cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:207–12. doi: 10.1002/jso.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebata T, Nagino M, Nishio H, Igami T, Yokoyama Y, Nimura Y. Pancreatic and duodenal invasion in distal bile duct cancer: paradox in the tumor classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer. World J Surg. 2007;31:2008–15. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong SM, Pawlik TM, Cho H, Aggarwal B, Goggins M, Hruban RH, Anders RA. Depth of tumor invasion better predicts prognosis than the current American Joint Committee on Cancer T classification for distal bile duct carcinoma. Surgery. 2009;146:250–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uenishi T, Kubo S, Yamazaki O, Yamada T, Sasaki Y, Nagano H, Monden M. Indications for surgical treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with lymph node metastases. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:417–22. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Campagnaro T, Pachera S, Valdegamberi A, Nicoli P, Cappellani A, Malfermoni G, Iacono C. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: prognostic factors after surgical resection. World J Surg. 2009;33:1247–54. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SG, Song GW, Hwang S, Ha TY, Moon DB, Jung DH, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Sung KB, Ko GY. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in the new era: the Asian experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:476–89. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Ohge H, Sueda T. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and surgical margin status for distal cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:207–12. doi: 10.1002/jso.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woo SM, Ryu JK, Lee SH, Yoo JW, Park JK, Kim YT, Jang JY, Kim SW, Kang GH, Yoon YB. Recurrence and prognostic factors of ampullary carcinoma after radical resection: comparison with distal extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3195–201. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9537-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimada M, Yamashita Y, Aishima S, Shirabe K, Takenaka K, Sugimachi K. Value of lymph node dissection during resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1463–1466. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ercolani G, Grazi GL, Ravaioli M, Grigioni WF, Cescon M, Gardini A, Del Gaudio M, Cavallari A. The role of lymphadenectomy for liver tumors: further considerations on the appropriateness of treatment strategy. Ann Surg. 2004;239:202–209. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000109154.00020.e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grobmyer SR, Wang L, Gonen M, Fong Y, Klimstra D, D’Angelica M, DeMatteo RP, Schwartz L, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Perihepatic lymph node assessment in patients undergoing partial hepatectomy for malignancy. Ann Surg. 2006;244:260–264. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217606.59625.9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juntermanns B, Radunz S, Heuer M, Hertel S, Reis H, Neuhaus JP, Vernadakis S, Trarbach T, Paul A, Kaiser GM. Tumor markers as a diagnostic key for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Med Res. 2010;15:357–361. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-15-8-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ni XG, Bai XF, Mao YL, Shao YF, Wu JX, Shan Y, Wang CF, Wang J, Tian YT, Liu Q, Xu DK, Zhao P. The clinical value of serum CEA, CA19-9, and CA242 in the diagnosis and prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su CH, Tsay SH, Wu CC, Shyr YM, King KL, Lee CH, Lui WY, Liu TJ, P’eng FK. Factors influencing postoperative morbidity, mortality, and survival after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1996;223:384–394. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199604000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takada T, Amano H, Yasuda H, Nimura Y, Matsushiro T, Kato H, Nagakawa T, Nakayama T Study Group of Surgical Adjuvant Therapy for Carcinomas of the Pancreas. Biliary Tract. Is postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy useful for gallbladder carcinoma? A phase III multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with resected pancreaticobiliary carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:1685–95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Nakashima A, Kondo N, Sakabe R, Ohge H, Sueda T. Prognostic factors after surgical resection for intrahepatic, hilar, and distal cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:651–658. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Nakashima A, Kondo N, Sakabe R, Ohge H, Sueda T. Adjuvant gemcitabine plus S-1 chemotherapy improves survival after aggressive surgical resection for advanced biliary carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;250:950–956. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3181b0fc8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerhards MF, van Gulik TM, González González D, Rauws EA, Gouma DJ. Results of postoperative radiotherapy for resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2003;27:173–9. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes MA, Frassica DA, Yeo CJ, Riall TS, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Donehower RC, Laheru DA, Hruban RH, Abrams RA. Adjuvant concurrent chemoradiation for adenocarcinoma of the distal common bile duct. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:178–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horgan AM, Amir E, Walter T, Knox JJ. Adjuvant therapy in the treatment of biliary tract cancer: a systematic review nd meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:1934–1940. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.5381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.André T, Tournigand C, Rosmorduc O, Provent S, Maindrault-Goebel F, Avenin D, Selle F, Paye F, Hannoun L, Houry S, Gayet B, Lotz JP, de Gramont A, Louvet C GERCOR Group. Gemcitabine combined with oxaliplatin (GEMOX) in advanced biliary tract adenocarcinoma: a GERCOR study. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1339–43. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patt YZ, Hassan MM, Aguayo A, Nooka AK, Lozano RD, Curley SA, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM, Schnirer II, Wolff RA, Charnsangavej C, Brown TD. Oral capecitabine for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and gallbladder carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101:578–86. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueno H, Okusaka T, Ikeda M, Takezako Y, Morizane C. Phase II study of S-1 in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1769–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]