Abstract

Backround: Surgical operations are alternative treatments in persons with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome who cannot tolerate continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy is a method with which somnolence is pharmacologically induced and collapse is evaluated through nasal endoscopy in patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Aims: We aimed to evaluate efficiency of dexmedetomidine or propofol used for sedation in patients undergoing drug-induced sleep endoscopy. Methods: A total of 40 patients aged between 18 and 65 years old in the ASA STATUS I-II group were included in the study. After premedicatıon wıth midazolam 0.05 mg/kg intravenously, patients were randomly divided into two groups and administered intravenous (iv) propofol with the loading dose of 0.7 mg/kg for 10 minutes, followed 0.5 mg/kg/h infusion (Group P); or dexmedetomidine with the loading dose of 1 mcg/kg for 10 minutes, followed by 0.3 mcg/kg/h infusion (Group D). Haemodynamic and respiratuary parameters, Bispectral index score, Ramsey sedation score, time to achieve sufficient sedation, surgeon’s and patients’ satisfaction, postoperative Aldrete score and side effects were recorded. Results: Time to achieve sufficient sedation, Bispectral index scores at 5, 10 and 15th. minutes intraoperatively, first Aldrete score in the recovery room, SpO2 values and respiratory rates all over the surgical procedure and in the recovery room were found lower in Group P (P<0.05). Bispectral index scores, mean arterial pressure and heart rate in the recovery room were significantly lower in Group D (P<0.05). Conclusion: Dexmedetomidine may be preferred as a safer agent with respecting to respiratory function compared with propofol in obstructive sleep apnea patients who known to be susceptible to hypoxia and hypercarbia.

Keywords: Obstuctive sleep apnea syndrome, drug induced sleep endoscopy, sedation, propofol, dexmedetomidine

Introduction

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSAS) is a syndrome characterized by the episodes of apnea or hypopnea due to obstruction in the upper airways [1]. The primary pathology is chronical intermittent hypoxia, resulting in the development of systemic inflammation and several comorbidities causing morbidity and mortality such as hypertension and stroke [2]. Surgical procedures of the upper airways are the treatment options especially for the patients who cannot tolerate continuous positive airway pressure therapy (CPAP) [3].

Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy (DISE) is a method with which somnolence is induced pharmacologically and obstruction in the upper airways is evaluated through nasal endoscopy in patients with OSAS [3-5].

Patients with OSAS are at a high risk for anesthesia-related mortality and morbidity. It is suggested that general anesthesia should be preferred to the deep sedation produced without providing safety of the airway. Whereas, general anesthesia applied on the OSAS patients for simple diagnostic and interventional procedures may eliminate the chance for being an ‘outpatient’ [6,7].

Use of sedative drugs providing rapid recovery without respiratory and cardiac depression in DISE procedures in these patients who are prone to develop hypoxia and hypercapnia will provide a safer sedation method. Benzodiazepines and propofol have been used alone or in combination for DISE [8,9]. Dexmedetomidine is a high selective α-2 adrenergic receptor agonist with anxiolytic and analgesic effects. As dexmedetomidine does not depress respiratory function and has a wide safety margin, it is preferable for anesthetists using in sedoanalgesia in the invasive procedures at the operation theatre as well as used in the intensive care unit [8-11].

In the literature, there are limited studies about the use of sedoanalgesic drugs in DISE. In this randomized, double blinded clinical study, we aimed to compare the sedative, haemodynamic and respiratory effects and, surgeon and patient satisfaction of dexmedetomidine and propofol in patients with OSAS undergoing DISE.

Methods

Study design, data collection and procedures

Our study was conducted on 40 patients in ASA STATUS I-II, aged between 18-50 years old, considering OSAS diagnosed by polysomnography undergoing nasal endoscopy under sedation for DISE procedure by the anesthesiology department of Erzincan University Mengücekgazi Training and Research Hospital.

Patients under 18 years old, drug or alcohol abusers or those having history of chronic analgesic use, patients who known to have allergy against the study drugs, those with IInd-IIIrd degree A-V block, patients with psychiatric disorders and those have Mallampati scores of III-IV were excluded from the study.

Following a fasting for 8 hours, patients were taken to the operating room and a perpheral intravenous cannulation on the dorsal side of the hand was performed. A balanced crystalloid (ISOLYTE-S, BRAUN, USA) 6 mL/h infusion was applied for 20 minutes. The infusion was maintenanced during the operation with a rate of 8 mL/h. Mean arterial pressure (MAP), peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR) (PHILPS MP-20 Philips Electronics Japan, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) and Bispectral index Score (BIS) (BISTM Complete 2-Channel Monitor and 4 Electrode Sensor, both from Covidien, Mansfield, MA,US) values and Ramsey Sedation Scores (RSS) were recorded.

All the patients were administered intravenous (iv) bolus of 0.05 mg/kg midazolam (DORMICUM, DEVA ILAC, ISTANBUL TURKEY) and randomly divided into two groups: In Group P (n=20), patients were administered iv propofol (PROPOFOL-LIPURA, B.BRAUN, MELSUNGEN AG, GERMANY) with the loading dose of 0.7 mg/kg for 10 minutes followed by the maintenance dose of 0.5 mg/kg/h; and in Group D (n=20), patients were administered iv dexmedetomidine (PRECEDEX, HOSPIRA, NORTH ROCKY MOUNT, USA) with the loading dose of 1 mcg/kg for 10 minutes followed by the maintenance dose of 0.3 mcg/kg/h. The maximal dexmedetomidine dose to be infused was planned as 0.6 mcg/kg/h. Dose of the drugs was titrated by increasing with 0.1 mg/kg/h propofol in Group P and 0.1 mcg/kg/h dexmedetomidine in Group D at 5 minute intervals until a sufficient sedation level was achieved.

Loading and maintenance doses of thr study drugs were infused by using infusion pumps (INFUSOMAT SPACE, B.BRAUN, MELSUNGEN AG, GERMANY) in both groups. Patients who did not reach to the desired sedation level despite the increased doses were excluded from the study. Infusion was terminated at the end of nasal endoscopy.

All patients received 2 L/minutes oxygen during the procedure through a nasal cannula.

Heart Rate, MAP, RR, SPO2, RSS and BIS values were recorded at 5 minute intervals; at 5, 10, and 15 minutes during the surgical procedure. Time to achieve sufficient sedation was recorded as minute (min).

Time to achieve sufficient sedation was defined as the duration between initiation of the drug infusion and the time when RSS:4 and BIS <75 values were obtained [12,31]. Aldrete recovery scores, haemodynamic and respiratory parameters, BIS, RSS and side effects, if occurs, were recorded when the patients arrived to the recovery room (0), and at 10, 20 and 30 minutes. After monitoring 30 min in the recovery room, patients were allowed to be taken to the ward with an Aldrete score >9, then monitored in the ward for 4 hours and discharged at the end of this duration. patients’ and surgeon’s satisfaction were recorded using 7-point likert-like verbal rating scale [32].

In case of heart rate dropped under 50 beats/minute and continued for 15 seconds in the intraoperative period, it was considered as bradycardia and atropine 0.5 mg iv was administered; similarly in case of MAP dropped by more than 30% of the initial value and continued for 60 seconds, rate of iv crystalloid infusion was raised to 20 ml/minute and hypotension therapy was planned. Oxygen administration of 5 L/minutes with a mask if SPO2 <92 and positive pressure ventilation with Ambu when the RR fell below 8 was added to the treatment protocol.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical package for Social Sciences for Windows version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics for each variable were determined. Normality of the data distribution was assessed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Median and minimum-maximum values were used for variables without normal distribution. Data with normal distribution were compared by Student’s t test Comparisons of continuous variables with asymmetric distribution were made by using the Mann-Whitney U test. A P value less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

No significant difference was found between the groups in terms of age, Body Mass Index (BMI), ASA scores, duration of the operation and, patient and surgeon’s satisfaction (P>0.05, Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data, duration of surgery, patient and surgeon’s satisfaction scores

| Age (years) | BMI (kg/m2) | ASA Scores (min-max) | Duration of Surgery (min) | Patients’ Sat (min-max) | Surgeon’s Sat (min-max) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group P | 43.3±10.6 | 28.9±3.9 | 1 (1-2) | 5.6±1.4 | 7 (6-7) | 6 (6-7) |

| Group D | 47.4±11.6 | 29.5±4.1 | 1 (1-2) | 5.1±0.8 | 7 (6-7) | 7 (6-7) |

BMI, Body Mass Index; ASA Sc, American Society of Anaesthesologists Score; Patient’s Sat, Patients’ Satisfaction Score; Surgeon’s Sat, Surgeon’s Satisfaction Score.

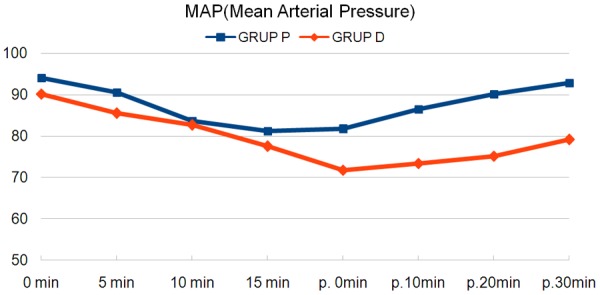

When haemodynamic data were examined, no significant difference was found between the groups in terms of intraoperative MAP and HR (P>0.05, Table 2; Figure 1). Whereas at the measurements in the recovery room, both MAP and HR values were found to be significantly lower in Group D (P<0.05, P<0.001, Table 2).

Table 2.

Haemodynamic and respiratory data

| Periods (min) | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | R 0 | R 10 | R 20 | R 30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP (mmHg) | ||||||||

| Group P | 94±7.5 | 90.6±8.4 | 83.7±7.2 | 81.3±7.6 | 81.7±7.9** | 86.6±7.6** | 90.2±7.3** | 92.9±6.9** |

| Group D | 90.2±7.1 | 85.6±7.9 | 82.7±8.2 | 77.6±10 | 71.8±7.9 | 73.4±7.8 | 75.2±8 | 79.2±8 |

| HR (min-1) | ||||||||

| Group P | 82.9±6.9 | 74.1±5.9 | 69.7±5.1 | 67.6±5.4 | 69.3±5.1* | 74.3±5.2** | 79.3±5.8** | 82.3±5.9** |

| Group D | 78.2±8.6 | 74.1±8.4 | 70.2±8.1 | 67.9±7.8 | 65.3±6.2 | 66.9±6.6 | 69.3±6.9 | 74±6.8 |

| SpO2 (%) | ||||||||

| Group P | 98±1.2 | 96.4±1.3* | 94.7±1.3** | 93.9±1.5** | 94.4±1.6** | 95.8±1.4** | 96.3±1.2** | 96.8±1.2** |

| Group D | 98±1.3 | 97.8±1.3 | 97.4±1.6 | 96.9±1.3 | 96.6±1.3 | 97.2±1.2 | 98±1.1 | 98.4±1.0 |

| RR (min-1) | ||||||||

| Group P | 15.8±1.4 | 13±0.9** | 11.1±0.9** | 10±0.8** | 10.2±1** | 12.2±1** | 13.2±1.5** | 14.2±1.1* |

| Group D | 16.6±2.1 | 15.9±2 | 15.2±2.1 | 14.7±1.9 | 14.2±1.8 | 14.7±1.5 | 15.5±1.5 | 15.9±1.6 |

R, recovery; MAP, Mean Arterial Pressure; HR, Heart Rate; RR, Respiratory Rate.

P<0.05, when compared with Group D;

P<0.001, when compared with Group D.

Figure 1.

Average of mean arterial pressures.

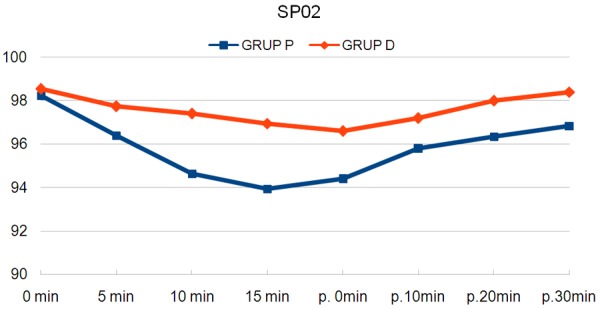

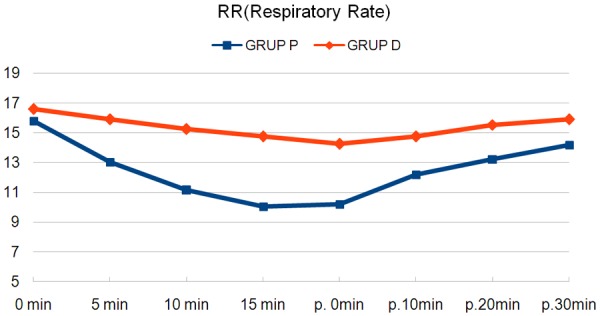

When respiratory data were evaluated; both SpO2 and RR were lower in Group P at all measurements (P<0.05, P<0.001, Table 2; Figures 2, 3). The lowest SpO2 value was found as 91% and the respiratory rate as 9; then, oxygen support was needed 1/20 patients in Group P (P>0.05).

Figure 2.

Average of oxygen saturations.

Figure 3.

Average of respiratory rates.

Time to achieve an adequate sedation was found to be significantly shorter in Group P (P<0.001, Table 3). Ramsey sedation scores were higher in Group P at the intraoperative 10th minute (P<0.001), while no significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of RSS in the other measurement times (Table 3). Bispectral Index scores were significantly lower in Group P at 5, 10 and 15 minutes (P<0.001). However, no significant difference was found between the groups in terms of the BIS scores at time to admission to the recovery room (P>0.05). BIS values were significantly higher at 10, 20 and 30 minutes in the recovery room in Group P (P<0.001, Table 3).

Table 3.

RSS: 4T, BIS, ramsay and aldrete’s scores

| RSS: 4T (min) | ||||||||

| Group P | 9±1.26** | |||||||

| Group D | 15.5±2.14 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Periods (min) | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | R 0 | R 10 | R 20 | R 30 |

|

| ||||||||

| RSS (min-max/med) | ||||||||

| Group P | 1 (1-2) | 2.5 (2-3) | 4 (3-4)** | 4 (3-4) | 4 (3-4) | 3 (2-4) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-1) |

| Group D | 2 (1-2) | 2 (2-3) | 3 (2-3) | 4 (3-4) | 4 (4-4) | 3 (3-3) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (1-2) |

| BIS (ort ± SD) | ||||||||

| Group P | 97.9±1.8 | 83.6±4.4** | 72.1±3.6** | 68±3.6** | 72.7±4.4 | 83.9±3.8** | 94.8±3.5** | 99.1±1.9** |

| Group D | 97.2±1.4 | 89.6±3 | 81.3±4.9 | 74±5.5 | 71.4±4.3 | 79±5.7 | 87±3.7 | 95.4±2.2 |

| ALD Sc (min-max/med) | ||||||||

| Group P | 7 (6-8)** | 8 (8-10) | 10 (9-10) | 10 | ||||

| Group D | 8 (8-9) | 9 (8-9) | 9 (9-10) | 10 (9-10) | ||||

R, recovery; RSS 4T, Ramsay Sedation Score: 4 Time; BIS, Bispectral Index Score; RSS, Ramsay Sedation Score; ALD Sc, Aldrete score; *, P<0.05;

P<0.001, when compared with Group D.

Aldrete score was found to be lower in Group P when arrived to the recovery room (P<0.001), no significant difference was found at other times of evaluation with respect to aldrete scores (Table 3).

No side effect was observed in both groups such as nausea, vomiting and desert mouth.

Discussion

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome (OSAS) is characterized by the episodes of apnea or hypopnea due to obstruction in the upper airways. If these patients are left untreated, systemic inflammation may develop and cause to several diseases leading to morbidity and mortality such as hypertension, stroke or metabolic syndrome [1,2].

Surgical therapy is applied as an alternative option in severe OSAS patients and in the patients who cannot tolerate CPAP [3]. Operations which directly target localization of the obstruction are the most successful surgical method in these patients. Nasal endoscopy during the natural sleep is known to be the most ideal diagnostic method to determine localization of the pathology. Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy (DISE), has been applied for the first time by Pringle and Craft [13], in which the upper airways are evaluated with fiberoptic nasal endoscopy during sleep produced by sedative drugs [1,4,5,14].

The most suitable option in the endoscopic procedures for both endoscopists and patients is to use a safe sedative agent which will not cause respiratory and cardiac dysfunctions [6]. We preferred propofol which is commonly used in the endoscopic procedures for sedation in patients undergoing DISE and, compared with dexmedetomidine which is recently being considered in the sedoanalgesic protocols [6,7,9].

Propofol has been used in different doses for sedation [6,7,9,10,12,16,17]. In some studies, sleep could not be produced at the desired level with bolus administration of propofol 1 mg/kg [15], and 2 mg/kg [20]. Moreover, the authors reported desaturation with inadequate sedation [15,20]. We administered propofol by infusion; loading dose followed by maintenance, instead of bolus injection. Whereas, in a sedoanalgesia protocol performed in patients undergoing vitroretinal surgery; when propofol was administered by iv infusion with 0.7 mg/kg loading and 0.5-2 mg/kg/h maintenance, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation have been found decreased with these doses [16]. Kaygusuz et al. [9] reported increase in the respiratory rate and decrease in oxygen saturation with propofol compared to dexmedetomidine. The authors had used loading dose of propofol as 6 mg/kg/h given for 10 minutes and maintenance dose was planned as 2.4 mg/kg/h [10]. In another study by Prachanpanich et al. [17] propofol was loaded with a dose of 1 mg/kg for 10 minutes followed by maintenance dose of 3 mg/kg/h; respiratory rate was found to be lower and need for oxygen support was found to be higher in the propofol group. In our study, we combined propofol with midazolam 0.05 mg/kg and defined the loading dose of propofol as (0, 7 mg/kg) for 10 minutes with the controlled infusion technique and, the maintenance dose of propofol was defined as 0.5 mg/kg/h. Both SpO2 and respiratory rates were lower in patients in propofol group compared to the patients administered dexmedetomidine. Although we did not observe severe desaturation in our patients, one of the patients in propofol group needed oxygen support. We also found that BIS values decreased and sedation score increased more rapidly in the propofol group; thus time to achieve adequate sedation was shorter in this group.

Dexmedetomidine is a high selective α-2 adrenergic receptor agonist and as a result of the stimulation of these receptors, central sympathetic activity decreases and, sedative and anxiolytic effects reveal [8,11]. This drug is known to show adrenergic effect with rapid loading. Therefore, loading dose is recommended to be administered slowly at least 10 minutes for the sympatholytic effect [6]. We applied the loading dose for 10 minutes and did not cause occurrence of sympathetic activity. Although dexmedetomidine temporarily increases the blood pressure and heart rate in the beginning, this effect is replaced by drops in the blood pressure and heart rate [8,11]. Some of the sedoanalgesia studies comparing dexmedetomidine and propofol reported that both drugs decrease MAP and HR with no significant differences observed between them [7,9,16]. It was demonstrated in some studies that, despite using widely, propofol caused bradycardia and hypotension; and dexmedetomidine had cardioprotective effects [10,25]. On the other hand, several studies in the literature demonstrated that dexmedetomidine is more associated with hemodynamic instability than propofol [6,26]. In our study, although propofol and dexmedetomidine were similar in terms of the haemodynamic parameters in the intraoperative period, MAP and HR values were lower in dexmedetomidine group in the recovery room after the drugs were discontinued (P<0.05, P<0.001). In addition, MAP and HR values raised in propofol group compared to the basal values at the 30. minute of recovery, neither MAP nor HR reached to basal values in the dexmedetomidine group. But this condition did not cause delayed recovery.

In a review on pediatric patients by Lin et al [18], use of dexmedetomidine in DISE was found to induce a natural sleep-like sedative response and thus enables a more accurate diagnosis of the localization and degree of the obstruction. Loading dose of dexmedetomidine has been applied as 1 mcg/kg for 10 minutes iv; maintenance dose used to be initiated with 0.2-0.4 mcg/kg/h and titrated with 0.1 mcg/kg/h in every five minutes [6,8,9,14,19]. Similarly, we applied the loading dose as 1 mcg/kg/h for 10 minutes and the maintenance dose as 0.3 mcg/kg/h.

Combined use of propofol, benzodiazepine, opioids or dexmedetomidine provides more advantages due to the synergistic effect compared to the using of these agents alone [7,9]. Muller et al. [26] has found that dexmedetomidine alone was not as effective as propofol combined with fentanyl for providing conscious sedation. We administered iv midazolam prior to loading of the study drugs in this study. We aimed to take advantage of the synergistic effect by adding midazolam to propofol and dexmedetomidine. We found that BIS values decreased and sedation score increased more rapidly in the propofol group; thus time to achieve adequate sedation was shorter in the propofol group. On the other hand, in dexmedetomidine group, we observed adequate sedation as well as respiratory stability.

Gross et al. [22] demonstrated that, there is a tendency to decrease in physiological responses against hypoxia and hypercapnia in OSAS and, susceptibility increases against anesthetic agents which have effects causing respiratory depression. Consistent with data from our study, the sedoanalgesia studies comparing propofol and dexmedetomidine have found higher respiratory rate and oxygen saturation in the blood in the dexmedetomidine group and they explained that propofol might cause hypotonia and depress breathing due to its muscle relaxant effects. They reported that dexmedetomidine provided a better respiratory stability and was more attractive drug for anaesthetist due to its the wide margin of safety [8-10,16,17,23,24]. Our results support these studies; in spite of we used low dose propofol with controlled infusion instead of bolus injection, peripheral oxygen saturation and respiratory rates were higher in dexmedetomidine group than propofol group. In addition, the lowest SpO2 value was recorded in propofol group during the procedure and oxygen support was needed.

BIS is a widely used method in sleep studies and the scores between 75-90 shows light sleep and the scores between 20 and 75 indicate to a deep sleep wave [27-29]. We found that BIS values higher and RSS was lower in dexmedetomidine group during the sedation.

In one study, use of propofol in DISE was criticized and the authors stated that this drug caused more hypotonia and muscle relaxation, lead to deeper sleep and might cause incorrect evaluations about the obstruction [8]. It was demonstrated in some studies that, patients sedated with dexmedetomidine are more cooperative than those sedated with propofol and that, dexmedetomidine provided a faster recovery period and earlier returning to the consciousness level [7,10,12]. In another study, time of stay in the recovery room was found similar with dexmedetomidine and propofol [16]. This was supported by our results; in this study Aldrete score at time of the admission to the recovery room were higher in dexmedetomidine group. In contrast, it was reported that, time of stay in the recovery room was longer in patients who received dexmedetomidine, thus it was concluded that the use of this drug as a sedoanalgesic agent should be limited [6,7,19,26,30].

In a study comparing propofol, benzodiazepines, opioids and dexmedetomidine for sedation patients and surgeons satisfaction were provided in all the drug groups [7]. Whereas, in another sedoanalgesia study comparing dexmedetomidine and propofol, surgeons satisfaction was similar in both groups, while patients satisfaction was higher in the dexmedetomidine group. The authors attributed this to dexmedetomidine provided a natural sleep-like pathway [16]. In our study, surgeons and patients satisfaction was found similar in propofol and dexmedetomidine groups.

In conclusion, our results suggest that, propofol provided rapid and deeper sedation and haemodynamic stability, and dexmedetomidine provided respiratory stability as well as adequate sedation for DISE. As patients with OSAS have higher risk to develope hypoxia and hypercapnia we suggest that, dexmedetomidine has advantages to propofol for sedation in patients with OSAS undergiong DISE.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Benton ML, Friedman NS. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome with nasal positive airway pressure improves golf performance. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:1237–42. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong Y, Dai Y, Wei G, Cha L, Li X. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on blood pressure in hypertensive patients with coronary artery bypass grafting and obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:4308–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vroegop AV, Vanderveken OM, Wouters K, Hamans E, Dieltjens M. Observer variation in drug-induced sleep endoscopy: experienced versus nonexperienced ear, nose and throat surgeons. Sleep. 2013;36:947–53. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanderveken OM. Drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) for non-CPAP treatment selection in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breath. 2013;17:13–4. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0671-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulualp SO, Szmuk P. Drug-induced sleep endoscopy for upper airway evaluation in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:292–7. doi: 10.1002/lary.23832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannallah M, Rasmussen M, Carroll J. Evaluation of dexmedetomidine/propofol anesthesia during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients with high probability of having obstructive sleep apnea. Anaesthesia, Pain & Intensive Care [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akarsu Ayazoğlu T, Polat E, Bolat C, Yasar NF, Duman U, Akbulut S, Yol S. Comparison of propofol- based sedation regimens administered during colonoscopy. Rev Med Chil. 2013 Apr;141:477–85. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872013000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathews AMV, Goh JPS, Teo LM. A case report on the Anesthetic Management of Dexmedetomidine-induced Sleep endoscopy and Transoral Robotic Surgery fort he Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare. 2013:2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaygusuz K, Gokce G, Gursoy S, Ayan S, Mimaroglu C, Gultekin Y. Comparison of sedation with dexmedetomidine or propofol during shockwave lithotripsy: a randomizedcontrolled trial. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:114–9. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000296453.75494.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Techanivate A, Verawattaganon T, Saiyuenyong C, Areeruk P. A Comparison of Dexmedetomidine versus Propofol on Hypotension during Colonoscopy under Sedation. J Anesth Clin Res. 2012;3:11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wan Q, Xu L, Bo Y. Effects of Dexmedetomidine combined with Dezocine on cognition function and hippocampal microglia activation of rats. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:2787–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasuya Y, Govinda R, Rauch S, Mascha EJ, Sessler DI, Turan A. The correlation between bispectral index and observational sedation scale in volunteers sedated with dexmedetomidine and propofol. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1811–5. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c04e58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pringle MB, Croft CB. A grading system for patients with obstructive sleep apnoea-based on sleep nasendoscopy. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1993;18:480–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1993.tb00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DE Corso E, Fiorita A, Rizzotto G, Mennuni GF, Meucci D, Giuliani M, Marchese MR, Levantesi L, Della Marca G, Paludetti G, Scarano E. The role of drug-induced sleep endoscopy in the diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: our personal experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2013;33:405–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Vito A, Agnoletti V, Berrettini S, Piraccini E, Criscuolo A, Corso R, Campanini A, Gambale G, Vicini C. Drug-induced sleep endoscopy: conventional versus target controlled infusion techniques--a randomized controlled study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:457–62. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1376-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghali A, Mahfouz AK, Ihanamäki T, El Btarny AM. Dexmedetomidine versus propofol for sedation in patients undergoing vitreoretinal surgery under sub-Tenon’s anesthesia. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:36–41. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.76506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prachanpanich N, Apinyachon W, Ittichaikulthol W, Moontripakdi O, Jitaree A. A comparison of dexmedetomidine and propofol in Patients undergoing electrophysiology study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96:307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin AC, Koltai PJ. Sleep endoscopy in the evaluation of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:576719. doi: 10.1155/2012/576719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeyneloglu P, Pirat A, Candan S, Kuyumcu S, Tekin I, Arslan G. Dexmedetomidine causes prolonged recovery when compared with midazolam/fentanyl combination in outpatient shock wave lithotripsy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;25:961–7. doi: 10.1017/S0265021508004699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li P, Zhou P, Shen P. [Feasibility study for the dexmetomidine utend the drug induced sleep endoscopy] . Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2014;28:1151–1154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin HC, Friedman M. Target-Controlled Infusion of Propofol-Induced Sleep Endoscopy for Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg September. 2013;149:272. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross JB, Bachenberg KL, Benumof JL, Caplan RA, Connis RT. Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:268–86. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200605000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu W, Chen Q, Zhang LC, Chen WH. Dexmedetomidine versus midazolam for sedation in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Int Med Res. 2014;42:516–22. doi: 10.1177/0300060513515437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sethi P, Mohammed S, Bhatia PK, Gupta N. Dexmedetomidine versus midazolam for conscious sedation in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2014;58:18–24. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.126782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leslie K, Tay T, Neo E. Intravenous fluid to prevent hypotension in patients undergoing elective colonoscopy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;34:316–21. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0603400314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller S, Borowics SM, Fortis EA, Stefani LC, Soares G, Maguilnik I, Breyer HP, Hidalgo MP, Caumo W. Clinical efficacy of dexmedetomidine alone is less than propofol for conscious sedation during ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:651–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babar-Craig H, Rajani NK, Bailey P, Kotecha BT. Validation of sleep nasendoscopy for assessment of snoring with bispectral index monitoring. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269:1277–9. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1798-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang P, Zhang Y, Yu H, Liu B. Effects of penehyclidine hydrochloride on the propofol dose requirement and Bispectral Index for loss of consciousness. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:2236–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sleigh JW, Andrzejowski J, Steyn-Ross A, Steyn-Ross M. The bispectral index: a measure of depth of sleep? Anesth Analg. 1999;88:659–61. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199903000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jalowiecki P, Rudner R, Gonciarz M, Kawecki P, Petelenz M, Dziurdzik P. Sole use of dexmedetomidine has limited utility for conscious sedation during outpatient colonoscopy. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:269–73. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200508000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reschreiter H, Kapila A. Sedation in adults. Surgery (Oxford) 2006;24-10:324–345. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health Measurement Scales. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide To Their Development And Use; pp. 28–53. [Google Scholar]