INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Medical education is expected to have an organic link with the community. If we look at the education related to modern medicine, there is a clear connect with the community in the form of rural health training centers (RHTCs) and urban health training centers (UHTCs). In fact, it is mandatory for a medical college to have functional RHTC and UHTC prior to approval from the Medical Council of India (MCI).[1]

These centers allow the undergraduate medical students an exposure to the rural and urban communities by which they can better understand the health issues of the communities, social determinants of health, treatment seeking behaviors, etc. During internship, the RHTCs and UHTCs offer the interns opportunities to sharpen their clinical and other skills. The centers also have an important role in the shaping up of postgraduate students, especially of the Community Medicine Department. They also serve as platforms for implementing the various national health programs, thus contributing to the national health goals. Through the RHTCs and UHTCs, general medical care as well as specialist care can be provided to the community. In addition, they open the doors for a wide range of community-based research, contributing to public health policy and programs.

While there is variation in the way these centers function across the country, several examples that establish their worth are available. Two of the more prominent ones include those at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi and the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sevagram, Wardha.[2,3]

In this regard, the AYUSH teaching institutes offer a stark contrast. The Central Council of Indian Medicine (CCIM) does not insist on community outreach services as a requirement for running an AYUSH college.[4,5,6] Hence, there is no stipulation for having RHTCs and UHTCs in AYUSH colleges. Consequently, the link of AYUSH teaching institutes with the community is almost nonexistent.

AYUSH has been traditionally rooted in the community, with Ayurveda dating back several centuries. The various traditions that have become a way of life for the community are a testament to this. In fact, for any system of medicine, the community base is naturally of great importance. It is therefore distressing to observe that the present AYUSH students get minimal exposure to the community during their education. Further, the community is also deprived of AYUSH services, both primary care as well as specialized care by different specialists. Since most of the AYUSH colleges do not have any attached community, it is very difficult to understand the community's health and other concerns, including the social determinants of health. This would also be an impediment in the overall development of the AYUSH students. Further, on account of a lack of such outreach, it is difficult to test various AYUSH interventions in the community for their acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness. Consequently, it becomes difficult to carve out a space for AYUSH in the national health programs. Thus, AYUSH services as well as education seem to be trapped in a vicious circle, wherein RHTCs and UHTCs offer a mechanism to make a positive difference.

The need for grounding the AYUSH colleges in the community was appreciated by the Planning Commission Steering Committee (PCSC) on AYUSH for the 12th Five Year Plan that recommended the assigning of territorial responsibility to AYUSH colleges to aid their contribution towards achieving the national health outcome goals.[7] Unfortunately, these recommendations were not pursued in the Plan document.

THE WAY AHEAD

It is imperative that the Department of AYUSH, as well as the CCIM, appreciate the need for establishing a community link for the AYUSH teaching institutes. At present, the RHTCs and UHTCs of medical colleges is the only comparable model available and hence used as reference. To begin with, on a pilot basis RHTCs and UHTCs should be established in select AYUSH colleges in the government sector with appropriate funding. The MCI norms for such centers in medical colleges may be useful in this regard. For instance, for an AYUSH college with 100 seats, the norms for the corresponding medical college may be referred to.[8]

The colleges should establish the RHTC in a nearby rural area that is approachable, needy and where good community participation is forthcoming. Similarly, the UHTC should be established in an urban area, preferably incorporating a slum area. The AYUSH colleges could then implement their ideas in a flexible manner, based on the community needs as well as the response elicited, enabling the centers to evolve.

Alternatively, the activities may be initiated in existing primary health centers and urban health centers of the government, where apart from service provision, students could be posted. This would be more cost-effective and offer means for integration with the various national health programs.

The day-to-day management of these centers may be entrusted to the department dealing with public health issues like the Swasthavritta Department in Ayurveda colleges. For this purpose, the capacities of these departments, especially in outreach and research, would need to be augmented. Alternatively, as suggested by the PCSC, a specific public health research-cum-outreach department may be set up in the AYUSH college for this purpose. Close relations should be established with the local public health facilities for better coordination.

Based on the learning of these experiments, and if found appropriate and useful, the concept could then be expanded to the other government as well as the private AYUSH colleges in a phased manner.

POTENTIAL ROLE FOR THE RURAL HEALTH TRAINING CENTERS AND URBAN HEALTH TRAINING CENTERS

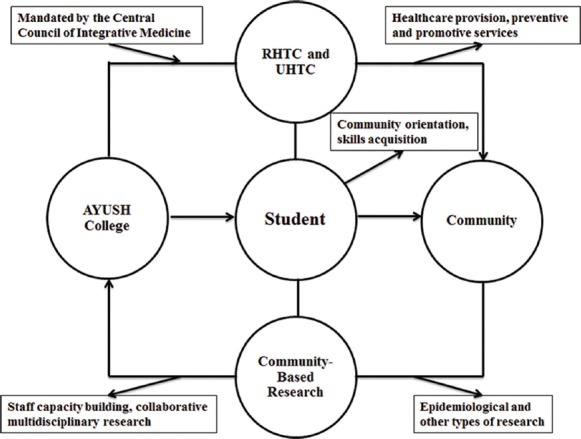

The RHTCs and UHTCs would have a significant role to play in several areas [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of AYUSH teaching institutes with functional rural and urban health training centers. The rural and urban health training centers established by the AYUSH colleges, as mandated by the Central Council of Indian Medicine, would benefit the community through a range of health services. The community would provide a platform for research activities, greatly benefiting the AYUSH colleges. Outcome of student exposure would be community orientation and skills acquisition. Thus, all the stakeholders stand to gain

Healthcare provision

Initially, the RHTCs and UHTCs should start with activities related to providing primary level healthcare to establish themselves in the community. Appropriate infrastructure should be put in place to facilitate the healthcare delivery. Adequate medical as well as paramedical and support staff should be deputed.

These centers would make the various AYUSH therapies accessible to the community members, a majority of whom may be aware of, yet unable to otherwise access them. A good example is the Panchakarma therapy, which may otherwise be unavailable and/or unaffordable to these people.

A schedule should be worked out where the various clinical departments of the college take turns in providing specialized medical services in the field.

The traditional health practitioners too can be involved in the primary level healthcare especially at the RHTCs, thus also aiding their mainstreaming.

The second phase of healthcare provision should include a limited range of indoor facilities, where the next level of specialized AYUSH care is possible.

Thus, the centers would be at the forefront of providing primary healthcare, as well as secondary care to an extent, linking up with the parent teaching hospitals for referring patients in need of tertiary care.

Extension services

Apart from the clinical services, the centers should take the lead in preventive and promotive activities in the community, something that has been acknowledged in the 12th Five Year Plan.[9] The draft National Health Policy too underscores the need for initiating community-based AYUSH interventions for preventive and promotive healthcare.[10] For instance, they can stress on promoting healthy diet and lifestyle. This is especially pertinent in the scenario of rising incidence of noncommunicable diseases in India, where AYUSH has a crucial role in prevention and control. The staff should chalk out appropriate programs for the community, like for instance, Yoga sessions in schools, healthy diet programs with women's self-help groups, managing common illnesses at the community level using AYUSH therapies, etc., linking up with NGOs wherever necessary.

Teaching-learning

In the teaching-learning process, these centers, especially after they have established themselves in the community, will offer unique opportunities to both the teachers as well as the students.

Recently, changes have been made to the community medicine part of the AYUSH undergraduate course syllabi. For instance, the Ayurveda Swasthavritta course syllabus contains in addition to topics on lifestyle and Yoga, subjects like epidemiology, the public health system, and national health programs.[11] Functional RHTCs and UHTCs having linkages with the public health system would facilitate the learning of these topics.

The students can better understand the relation between social determinants such as economic status, education, occupation, housing, social status, etc., with the health status. They will appreciate the importance of the family as a unit when understanding disease etiology and while planning interventions.

Some of the interns can be conveniently attached to the RHTC and/or UHTC during their internship, which would help them in polishing their clinical as well as soft skills. Suitable arrangements for their stay would need to be made.

Postgraduate students can do their dissertations at the RHTC and/or UHTC and could also conduct small studies in the community to understand the demographics, socioeconomic profile, health status, etc.

The CCIM would need to develop a proper framework for incorporating the RHTC and UHTC postings within the curriculum.

It is understood that such postings may be fraught with several issues. For instance, it is commonly observed that the period of internship is not effectively utilized to develop and refine skills.[12] This could be countered by developing an effective way of implementation and an objective way of the assessment of the postings.

Community-based research

While providing healthcare services, it is also important to understand the health and other issues facing the respective communities. Exploratory field studies should be initiated for this purpose. This will also help build rapport with the community and pave the way for systematic research, including clinical research in due course of time. Another important area of research is that of the local health traditions, which can be documented and preserved.

Meaningful and sustained research in the community would go a long way in assessing the status of AYUSH in the community, weighing the success of different therapies, addressing cost of care issues and improving the acceptability of AYUSH in the community. It will also help build the research capacities of the staff of AYUSH colleges and foster a research atmosphere, also generating possibilities of multi-disciplinary collaborative research.

Role in national health programs

Last but not the least, RHTCs and UHTCs will enhance the role of AYUSH in the national health programs. Pilot projects can be conveniently implemented in these settings, the findings of which can be used for replication on a large scale. Effectiveness of different public health strategies too can be studied.

CONCLUSION

It is strongly recommended that RHTCs and UHTCs be made an integral part of all the AYUSH teaching institutes in a time-bound manner.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions to the article.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.New Delhi: Medical Council of India; 2012. Medical Council of India. Requirements to be Fulfilled by the Applicant Colleges for Obtaining Letter of Intent and Letter of Permission for Establishment of the New Medical Colleges and Yearly Renewals Under Section 10-A of the Indian Medical Council Act, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi. Comprehensive Rural Health Services Project (CRHSP), Ballabgarh. [Last cited on 2014 Nov 27]. Available from: http://www.aiims.edu/aiims/departments/ccm/Rural%20health%20Program.pdf .

- 3.Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences. Community Activities. [Last cited on 2014 Nov 27]. Available from: http://www.mgims.ac.in/index.php/community/community-based-medical-education .

- 4.The Indian Medicine Central Council (Minimum Standard Requirements of Ayurveda Colleges and attached Hospitals) Regulations. 2012. [Last cited on 2014 Nov 27]. Available from: http://www.ccimindia.org/cc_actregulations_2012.html .

- 5.The Indian Medicine Central Council (Minimum Standard Requirements of Siddha Colleges and attached Hospitals) Regulations. 2013. [Last cited on 2014 Nov 27]. Available from: http://www.ccimindia.org/cc_actregul_siddha_2013.html .

- 6.The Indian Medicine Central Council (Minimum Standard Requirements of Unani Colleges and attached Hospitals) Regulations. 2013. [Last cited on 2014 Nov 27]. Available from: http://www.ccimindia.org/cc_actregul_unani_2013.html .

- 7.Report of Steering Committee on AYUSH for 12th Five Year Plan. [Last cited on 2014 Nov 27]. Available from: http://www.planningcommission.nic.in/aboutus/committee/strgrp12/st_ayush0903.pdf .

- 8.New Delhi: Medical Council of India; 2011. Medical Council of India. Minimum Standard Requirements for the Medical College for 100 admissions annually Regulations, 1999 (Amended up to November 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volume III. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd; 2013. Planning Commission of India. Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012-2017). Social Sectors. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Health Policy Draft. [Last cited on 2015 Jan 27]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/showfile.php?lid=3014 .

- 11.Central Council of Indian Medicine, New Delhi. Syllabus of Ayurvedacharya (BAMS) 3rd Year. [Last cited on 2014 Nov 27]. Available from: http://www.ccimindia.org/downloads/3rd%20year%20syllabus.pdf .

- 12.Sood R, Adkoli BV. Medical education in India: Problems and prospects. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2000;1:210–2. [Google Scholar]