Abstract

This article summarizes the proceedings of a symposium of the 2001 RSA Meeting in Montreal, Canada. The chair was Antonia Abbey and the organizers were Tina Zawacki and Philip O. Buck. There were four presentations and a discussant. The first presentation was made by Maria Testa whose interviews with sexual assault victims suggest that there may be differences in the characteristics of sexual assaults in which both the victim and perpetrator were using substances as compared to when only the perpetrator was using substances. The second presentation was made by Tina Zawacki whose research found that perpetrators of sexual assaults that involved alcohol were in most ways similar to perpetrators of sexual assaults that did not involve alcohol, although they differed on impulsivity and several alcohol measures. The third presentation was made by Kathleen Parks who described how alcohol consumption affected women’s responses to a male confederate’s behavior in a simulated bar setting. The fourth presentation was made by Jeanette Norris who found that alcohol and expectancies affected men’s self-reported likelihood of acting like a hypothetical sexually aggressive man. Susan E. Martin discussed the implications of these studies and made suggestions for future research.

Keywords: Alcohol Consumption, Sexual Assault, Alcohol Problems, Prevention

INTRODUCTION

Approximately half of sexual assaults involve alcohol consumption by the perpetrator, the victim, or both. This information on its own does not indicate if alcohol’s psychological or pharmacological effects contribute causally to sexual assault or if the relationship is spurious. Researchers have used two paradigms to examine alcohol’s role in sexual assault: (1) surveys of victims’ and perpetrators’ perceptions of sexual assault experiences and (2) laboratory studies that examine alcohol’s effects on responses to sexual and/or aggressive stimuli. Each research paradigm has its strengths and limitations. Surveys of victims and perpetrators have high external validity; however, they cannot unequivocally demonstrate causality. Laboratory studies have high internal validity, however, they cannot measure actual sexually assaultive behavior. Therefore, researchers must conduct both types of studies to fully explicate alcohol’s role. This symposium brought together research with women and men participants that used survey and laboratory methodologies. Finding similar results with complementary methodologies and samples increases confidence in the conclusions.

Antonia Abbey

UNDERSTANDING INCIDENTS OF SEXUAL AGGRESSION: FOCUS ON THE ROLE OF ALCOHOL

Maria Testa and Jennifer A. Livingston

A growing body of research has attempted to understand the impact of alcohol on sexual assault outcomes at the event level. To the extent that alcohol contributes to offender aggression and victim impairment, alcohol use by either perpetrator or victim should be related to more severe outcomes. Severity of outcomes are typically arrayed on a continuum, ranging from sexual contact to coercion, attempted rape, and rape as the most severe. Results of these event-level studies are mixed (Brecklin and Ullman, 2001; Martin and Bachman, 1998; Testa and Livingston, 1999; Ullman et al., 1999a, 1999b).

One reason for the discrepancy may be that some studies have examined the simultaneous effects of victim and perpetrator substance use, whereas others have examined the effects of only the victim’s or only the perpetrator’s alcohol use. Another possibility is that although victim and perpetrator substance use are often in concert, there are more incidents in which only the perpetrator is drinking than vice versa. This discrepancy is fairly small in college student samples; however, it becomes larger in the community samples. For example, in Ullman and Brecklin’s (2000) analysis of Wilsnack’s data, 100% of the incidents in which the victim was drinking involved perpetrator drinking. However, of the incidents in which the victim was not drinking, 42% involved a perpetrator who was drinking. Thus, examination of the role of alcohol in sexual assault requires consideration of three types of assault: those in which both were drinking, those in which neither were drinking, and those in which the perpetrator but not the victim was drinking. The present study compared assault characteristics and severity of these three different types of assault. Further, we examined the characteristics of the women who experience these different types of assault relative to women with no sexual assault history.

The sample consisted of 175 women who responded positively to one or more items on the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss et al., 1987) and provided a description of their most recent sexual assault incident. Women, 18 –30 years old, were recruited through random digit dialing in the Buffalo NY area as part of an NIAAA-sponsored longitudinal study of alcohol and sexual assault. Based on the woman’s reports of her own and the perpetrator’s substance use, we categorized incidents involving substance use by both victim and perpetrator (n = 75), substance use by the man only (n = 39) or no substance use (n = 58). Three incidents that involved substance use by the woman but not the man were not included in analyses. The most commonly used substance was alcohol, however some incidents included drug use in addition to or instead of alcohol.

Consistent with previous research (e.g., Abbey et al., 1996), incidents involving mutual substance use were more likely to originate outside of the home (e.g., bar, party) and to involve a perpetrator who was not an intimate partner compared to incidents in which neither or only the man was drinking. In addition, incidents involving mutual substance use were more severe, in that they were more likely to involve rape than sexual coercion. Incidents in which neither or the man only was using substances did not differ from each other on any variable. Given the contextual differences between mutual and man only substance use incidents, we subsequently examined the association between number of drinks consumed by the perpetrator and severity of assault separately for these two types of incidents. In incidents in which only the man was drinking, there was a strong positive correlation between number of drinks and severity. When both were drinking, the correlation between perpetrator alcohol consumption and severity became nonsignificant; however, there was a positive correlation between victim alcohol consumption and severity.

We also compared women who experienced the three types of sexual assault with women reporting no sexual assault history. Consistent with prior research (e.g., Gidycz et al., 1995), women reporting any type of sexual assault reported more sexual partners and earlier initiation of sexual activity than women without sexual assault. Also as expected (Marx et al., 2000), women experiencing sexual assaults involving mutual substance use reported more alcohol and drug use and higher prevalence of lifetime alcohol dependence.

Unexpected differences also emerged. Women who experienced assaults involving a substance-using perpetrator reported lower income, lower rates of employment, and the highest rates of partner physical aggression and injury. These women, as well as those experiencing nonsubstance related sexual assaults, also reported low sexual assertiveness and high rates of childhood sexual abuse. In contrast, women experiencing sexual assaults involving mutual substance use did not show decrements in sexual assertiveness and reported rates of childhood sexual abuse that were only moderately elevated relative to the no assault group.

Findings suggest distinct subtypes of sexual assault, characterized by different contextual factors and different individual risk factors. Sexual assaults involving mutual substance use tend to involve acquaintances rather than intimates, to originate outside the home, and to result in rape or attempted rape rather than sexual coercion. Women experiencing these assaults report high levels of consensual sexual activity and substance use; however, on many variables they do not differ from the no assault group. In contrast, sexual assaults in which the woman is not using substances tend to occur at home and to involve sexual coercion from intimate partners. Women experiencing these types of assault, particularly those experiencing assault from a substance-using perpetrator, show low sexual assertiveness, high rates of childhood sexual abuse, high rates of partner physical violence, and low income. Findings suggest two potential pathways to sexual assault, one involving risky behaviors and the other involving poverty and abusive relationships.

Sexual assaults in which the woman is drinking may be easier to prevent because of the possibility of behavioral change. In contrast, incidents not involving victim substance use appear to arise from factors less amenable to change: poverty, childhood sexual abuse, abusive relationships and low sexual assertiveness.

PREDICTING ALCOHOL USE DURING SEXUAL ASSAULT: DIFFERENCES IN PERPETRATORS’ PERSONALITY, ATTITUDES, AND EXPERIENCES

Tina Zawacki, Philip O. Buck, Antonia Abbey, Pam McAuslan, and A. Monique Clinton

Approximately 50% of sexual assaults involve alcohol consumption by the perpetrator, victim, or both (Abbey et al., 1996; Koss et al., 1987). Studies that have addressed alcohol’s involvement in sexual assault have focused primarily on the presence of alcohol and its impact on perpetrators’ level of force, victim resistance, and physical injuries (Martin and Bachman, 1998; Ullman et al., 1999a, 1999b). Although studies of sexual assault have examined characteristics of perpetrators in general, little attention has been paid to individual differences that may exist between men who perpetrate sexual assault under the influence of alcohol versus sober. Thus, the present study explores differences among men who never perpetrated sexual assault, men who perpetrated sexual assault that did not involve alcohol, and men who perpetrated alcohol-involved sexual assault.

Based on previous research regarding sexual assault perpetration, it was hypothesized that as compared to nonperpetrators, perpetrators, whether they used alcohol or not, would have engaged in more delinquent behaviors; be more aggressive, dominant, and impulsive; have less empathy and weaker social skills; date and misperceive women’s friendliness as sexual interest more frequently; be more approving of casual sex; and have more traditional gender role beliefs as compared to nonperpetrators. Differences were also anticipated between the two groups of perpetrators. As compared to perpetrators who committed sexual assaults that did not involve alcohol, alcohol-involved perpetrators were expected to consume more alcohol in general as well as in potential dating and sexual situations. Additionally, alcohol-involved perpetrators were expected to have stronger sexual alcohol expectancies.

Participants were 361 male undergraduates at a large, urban university (M age = 25). Fifty-six percent of the sample were Caucasian, 31% were African-American, 6% were Arabic or Middle-Eastern, 2% were Hispanic, 3% were Asian, and 2% either had another ethnic background or did not answer this question.

Participants completed a self-administered questionnaire and received $20. Sexual assault perpetration since age 14 was measured using a 16-item expanded version of the sexual experiences survey (Koss et al., 1987). Standard measures were also included of the antisocial, dating, and alcohol-related beliefs and behaviors that were described in the hypotheses.

Fifty-eight percent (n = 209) of participants indicated that they had committed a sexual assault. Fifty-four percent of perpetrators (n = 114) committed at least one assault that involved alcohol consumption by either the perpetrator, the victim, or both. In 95% of the assaults that involved drinking, the man had consumed alcohol; in 82% of these incidents both the man and woman consumed alcohol. Respondents were classified into one of three mutually exclusive groups based on perpetrator status: nonperpetrator (n = 152), no alcohol-involved perpetrator (n = 95), and alcohol-involved perpetrator (n = 114).

Hypotheses regarding differences between nonperpetrators and perpetrators were largely supported using discriminant function analysis. As compared to nonperpetrators, both no alcohol-involved and alcohol-involved perpetrators reported a stronger history of delinquency, a more aggressive and sexually dominant personality style, more frequent dating, more frequent misperception of women’s friendliness as sexual interest, greater endorsement of casual sex, and more traditional gender role beliefs. Additionally as compared to both nonperpetrators and no alcohol-involved perpetrators, alcohol-involved perpetrators reported greater alcohol consumption during dates, stronger beliefs that alcohol enhances sexuality, stronger beliefs that women’s drinking is a cue of sexual interest, and a more impulsive personality. Alcohol-involved perpetrators reported greater monthly alcohol consumption than nonperpetrators, but their consumption did not differ from that of nonalcohol-involved perpetrators.

By and large, these data suggest that predictors of sexual assault perpetration that have been documented in past research such as general personality characteristics and dating-related beliefs and behaviors do not differentiate between men who perpetrated sexual assault with or without alcohol; both types of perpetrators evidence greater aggressiveness and casual sexual behavior. Men who committed sexual assaults that involved alcohol did stand out in terms of their greater alcohol consumption in potential sexual situations and their strong sexual alcohol expectancies. Interestingly, alcohol-involved perpetrators did not differ significantly from no alcohol-involved perpetrators in usual alcohol consumption, suggesting that it is important to focus on the use of alcohol in dating and sexual situations in models of alcohol’s role in sexual assault, rather than only on general drinking patterns.

According to cognitive deficit theories of alcohol’s effects, intoxication narrows the drinker’s perceptual field so that they focus on what is most salient in the situation (Steele and Josephs, 1990; Taylor and Leonard, 1983). Alcohol-induced cognitive deficits may exacerbate some men’s tendency to mistakenly see sexual meaning in women’s friendly behavior. Impulsive men’s already low ability to inhibit their behavior may be exacerbated by the cognitive deficits caused by alcohol. The findings that alcohol-involved perpetrators drank more in sexual situations, had stronger sexual alcohol expectancies, and were more impulsive, suggest that when drinking alcohol with a woman, these men focus on their own sexual desire and any signs that she is interested in having sex and impulsively act on them.

HOW ACCURATE ARE WOMEN’S PERCEPTIONS OF THEIR OWN BEHAVIOR AFTER DRINKING?

Kathleen Parks and Cheryl L. Kennedy

Previous research suggests that women are at greater risk for experiencing aggression associated with drinking in a bar when they have more contact and interactions with men, experience more behavioral impairment after consuming alcohol, and have made riskier choices (e.g., leaving alone with a man, bringing a man to her home) when interacting with male strangers in the past (Parks et al., 1998; Parks and Zetes-Zanatta, 1999). Changes that occur in a woman’s behavior after alcohol consumption may increase her risk for experiencing sexual aggression, by making her more vulnerable or a more apparent target to a potential perpetrator. In addition, both consuming alcohol and certain behavioral changes that can occur after alcohol consumption (e.g., increased talking, smiling) might be perceived as greater romantic or sexual interest by a male (Abbey, 1987; George et al., 1988), particularly in settings such as bars.

To evaluate changes in behavior that occur after alcohol consumption during heterosexual interactions, female participants were observed interacting with male confederates in a bar laboratory. The women’s perceptions of a social interaction with a male stranger and changes in their own behavior after consumption of either a low (0.00 –0.02 g/100 ml Blood Alcohol Level; BAL) or high (0.08 g/100 ml BAL) dose of alcohol were assessed.

We hypothesized that: (1) women in the high dose alcohol condition would report greater changes in their own behavior and in the behavior of the male confederate than women in the low dose alcohol condition, (2) the male confederates would report greater changes in behavior in the women who consumed the high versus the low dose of alcohol, and (3) there would be observable differences in the behavior of women in the high and low dose alcohol conditions, particularly in response to the male’s behavior.

Fifty-six women participated in the study, 28 in the low dose alcohol condition and 28 in the high dose alcohol condition. All of the women were single, most were European-American (87.5%), and the average age was 23.5. Most (67.9%) of the women reported going to bars 2–3 times each week and reported consuming an average of 5.4 drinks on a typical occasion in a bar. They were required to meet all standard criteria for participating in alcohol research (including taking a pregnancy test) and were paid $10 per hour for their participation. A female research assistant acted as the bartender. Two male confederates were trained to interact one-on-one with the female participants who were scheduled in pairs. The male confederates arrived at the Research Institute at the same time as the female participants and were presented as male participants in the study.

The participant and confederates were seated in pairs at the bar. The interactions between the women and confederates lasted approximately 1.5 hr. During the first 20 min, they engaged in a “getting acquainted” interaction. Next, the female participants consumed the amount of alcohol required to achieve the desired BAL in either three or four drinks over a 20-min period while continuing to interact with the male confederates. The male confederates consumed a similar quantity of nonalcoholic beverage. The two participants and two confederates then engaged in a group activity (e.g., darts, cards) for 20 min to allow for absorption of the alcohol. Each pair then returned to the bar, was breathalyzed, and continued to interact for a final 20-min period.

During this final interaction, the male confederates were trained to engage in five overt, sexually suggestive “probe” behaviors: complimenting her appearance, moving closer, touching her arm, touching her hair, and whispering in her ear. Each probe behavior was designed to be more intrusive than the previous probe (Cue et al., 1996).

Women in the high dose condition reported feeling more impaired, slow, fuzzy, dizzy, clumsy, loud, and aggressive than low dose condition women. The male confederates rated the high dose condition women as more impaired, fuzzy, dizzy, clumsy, loud, and aggressive than the low dose condition women. They also rated the high dose participants as more expressive, sexual, friendly, relaxed, talkative, sociable, sexy, outgoing, and humorous than the low dose participants.

Observations of several nonverbal, discrete behaviors corresponded to the subjective descriptions of the women’s behavior. We observed higher rates of smiling, frowning, and arm/hand movements and lower rates of head movements and face scratching among women in the high dose condition compared with women in the low dose condition across the drinking and probe interactions. Changes in receptive behavior were observed among women in the high dose condition from the drinking to probe interactions. These women exhibited less open, more neutral and more closed body positions during the probe interaction.

Why were the male confederates’ subjective ratings of the high dose women as more sexual, sexy, and outgoing contradictory to the actual observations of their behavior? These contradictions support the idea that males misperceive women’s friendly behavior as sexual intent. Clearly friendly and verbal behavior increased, but actual signals of receptivity (e.g., body more open) did not. Thus, it appears that friendly more expressive behavior is seen as sexual interest even among males trained to be objective when interacting with a woman who is drinking alcohol. This further suggests that educating women about the changes that occur in their own behavior after consuming alcohol and how these changes are perceived by men may be an effective means for reducing misperceptions and the potential for sexual assault.

ALCOHOL’S DISTAL AND PROXIMAL EFFECTS ON MEN’S SELF-REPORTED LIKELIHOOD OF SEXUAL AGGRESSION

Jeanette Norris, William H. George, Kelly Cue Davis, and Joel Martell

Research findings consistently show that alcohol consumption is involved in the majority of acquaintance sexual assault (Abbey et al., 1998; Koss, 1988; Muehlenhard and Linton, 1987). In addition, men’s self-reported likelihood of committing rape has been associated with positive responding to violent pornographic depictions, especially when the rape victim is portrayed as sexually aroused (see Malamuth, 1984 for a review). Given the individual influence of alcohol consumption and use of violent pornography, an examination of their interaction may be especially useful in learning how some men find it acceptable to obtain sex through force. This study investigated the pathways through which alcohol’s physiologic and expectancy effects influenced men’s responses to and judgments of a violent pornographic story and ultimately their self-reported likelihood of committing sexual aggression against a woman.

Although pharmacological and expectancy effects of alcohol can individually influence men’s responses to a pornographic depiction of a rape, an important question still to be addressed concerns the interactive effects of expectancy and pharmacological effects on responses to violent pornography and men’s likelihood of committing sexual assault. The inclusion of both pre-existing alcohol expectancies and situational alcohol consumption variables in an experimental design allows for testing both distal and proximal mediation and moderation hypotheses. Specifically, the distal variable included in this study was the a priori sex-related alcohol expectancy measure (Leigh, 1990). The proximal manipulated variables of interest to this paper included expectancy set and actual alcohol ingestion. The ultimate outcome variable in this study was men’s self-reported likelihood of behaving like a sexually aggressive male story character. In addition, we included dependent measures of subjects’ perceptions of story elements and their own sexual and affective reactions to the story to test for their potential mediating effects.

One hundred thirty-five male social drinkers between the ages of 21 and 45 (M = 28.6) were recruited through local newspaper advertisements in a large west coast city. Participants were screened to establish that they were free of health problems that would contraindicate alcohol consumption. Extremely heavy drinkers (more than 35 drinks per week) and abstainers (less than one drink per week) were excluded. Participants were paid $35 for the laboratory session and $5 for returning a follow-up questionnaire.

Three participant beverage conditions were employed (alcohol-expect/receive alcohol; placebo-expect alcohol/receive tonic; control-expect/receive tonic). Participants took part in the study individually with male experimenters and “bartenders.” The experiment consisted of two stages that were presented as two separate studies. In the first stage, the participant was left alone to complete a computerized alcohol expectancy questionnaire concerned with sexuality (Leigh, 1990) and a demographic questionnaire. During the second stage, the participant was administered the appropriate beverage after which he read the computerized story and completed the dependent measures. The dependent measures consisted of several seven-point scales that assessed participants’ sexual arousal, affect, perceptions of force used by the male character, perceptions of the female character, and participants’ likelihood of behaving like the sexually aggressive male story character.

Alcohol dose was determined by weight. The participant was given a dose of 100-proof vodka to raise his BAL to 0.06 g%. The total volume of liquid consumed was also determined by weight so that participants in all conditions consumed the same amount of liquid relative to body weight. Bartenders were blind to bottle content for both the alcohol and the placebo conditions.

The bartender provided the expectancy manipulation by telling the participant that he had been assigned to the alcohol condition (for both the alcohol and placebo conditions) or to the tonic condition. The participant had 3 min to consume each of 3 drinks after which the participant was left alone for 20 min so that any alcohol could be absorbed into the bloodstream. After a breath analysis, the bartender told the participant either that his BAL was still at 0.0 (for participants in the no alcohol condition), or that his BAL was “about 0.06” (for participants in the alcohol and placebo conditions) regardless of the true results of the analysis.

The findings can be summarized as follows: (1) Both the distal effects of a priori sex-related alcohol expectancies and the proximal effects of expected and actual alcohol consumption increased men’s self-reported likelihood of behaving like a hypothetical sexually aggressive man. These effects occurred through the direct effects of alcohol expectancies and their interaction with consumption, as well as through the mediated effects of participants’ affective reactions to the story and judgments about the story characters. (2) Men who were high in alcohol expectancies and received alcohol rated themselves as more likely to behave like the male character than did high alcohol expectancy men who did not receive alcohol and low alcohol expectancy men. It appears that alcohol consumption by high alcohol expectancy men may increase their inclination toward sexual aggression. (3) Higher alcohol expectancies also increased men’s estimations of their sexual aggression likelihood through three mediated pathways: participant positive affective reaction; perceptions of force; and perceptions of the female character’s enjoyment. As predicted, men with greater alcohol expectancies reacted with more positive reactions. In turn, these positive feelings led to the participants perceiving less force and more female enjoyment, potentially as a means of maintaining (or at least not challenging) pleasant feelings generated by the story. A higher level of alcohol expectancies also directly resulted in decreased perceptions of force and increased perceptions of female enjoyment. (4) The crucial variable in predicting sexual aggression likelihood through these mediated paths appeared to be perceptions of how much the female character enjoyed herself: Both participants’ positive reactions and perceptions of force operate through that variable. Participants reported a greater likelihood of behaving like the male character in the story if they perceived the female character as having a good time. (5) Alcohol ingestion independently lowered participants’ perceptions of force and increased participants’ perceptions of the female character’s enjoyment. This finding indicates the presence of an alcohol “myopia” effect rather than an expectancy effect (Steele and Josephs, 1990; Taylor and Leonard, 1983).

SIGNIFICANCE

Susan E. Martin

Like many researchers, these four authors have found that alcohol consumption is highly correlated with sexual assault. However, like the proverbial blind person, each appears to have touched a different part of the “elephant” of sexual aggression in addressing the contributing factors (including alcohol consumption) that result in sexual assault. Moreover, their approaches illustrate the ethical limitations that researchers face in teasing apart the ways that alcohol may contribute to sexual assault. They are restricted in the use of the usual methodology of much of alcohol research — the field experiment — so they cannot study sexual violence directly for obvious ethical reasons. Thus researchers must use indirect approaches like those presented today.

Two of the studies used laboratory experiments that provide a surrogate for sexual aggression. Norris et al. use a vignette depicting a sexual assault and explore the male reader’s responses to it comparing men who know they have consumed alcohol, those who believe they have consumed alcohol, and a group that is aware that they are not receiving alcohol. Parks and Kennedy study heterosexual interaction in a bar laboratory setting to identify changes in the verbal and nonverbal behavior of women who had consumed either low and high doses of alcohol as well as nondrinking male confederates’ perceptions of the changes following brief interaction periods. Although such studies have internal validity, they are subject to concerns about generalizability.

In contrast, Testa and Livingston and Zawacki and colleagues present data from surveys that explore the experience of sexual aggression and try to pinpoint the contributing individual and situational factors including the role of alcohol. While exploring real-world experiences, surveys are subject to retrospective recall problems and obtain data only from the perspective of one of the participants in the interaction. This is not a criticism of the papers; it simply acknowledges the limitations on researchers that make this line of study so difficult.

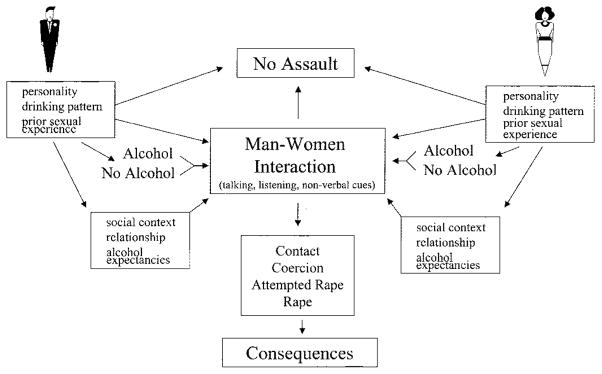

In addition to using differing methodologies, these papers also vary with respect to whose point of view they present. All the authors recognize that to understand sexual aggression or assault one must explore both proximal and distal factors that may affect an interaction between two people. Nevertheless, each paper provides a different but limited perspective on that interaction. Figure 1 presents a conceptual model to represent this process.

Fig. 1.

Factors predicting intoxicated sexual assault.

In the center is the proximal heterosexual interaction that either results in a sexual assault of some type or does not result in assault. Each of the participants (male on the left side, female on the right) has consumed or has not consumed alcohol (and the quantity may vary). Both interact in a particular social setting where there may or may not be peers, observers, or “guardians” present who may encourage or discourage an assault. The social environment also includes the relationship between the male and female, the immediate alcohol expectancies of each, and the pharmacological effects of the alcohol. In addition, distal factors that affect the event include each participant’s attitudes, personality/temperament, and experiences with normative heterosexual interaction, sexual intercourse, and alcohol consumption patterns. Each of the studies might be located at different places within this conceptual diagram with respect to the study’s focus.

As social scientists, we need to get at the interaction process that is at the center of Fig. 1 in order to understand what happens between a man and woman (to start with heterosexual interactions) in terms of cues, come-ons, perceptions, misperceptions, and the communication process — both verbal and nonverbal. Use of a common language and measures by researchers and broadened scales to address overlooked situations would foster such understanding.

These papers suggest several directions for research on the role of alcohol in sexual assault. First, since alcohol and drug use may play different roles in varied situations, these complex relationships need study. Second, men and women come into interactions with expectancies but these change as the interactional process unfolds and this process needs further study. Third, researchers also need to move into developing and testing creative interventions to forestall alcohol-related sexual assault. Although this will not be easy, it will be rewarding.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from NIAAA: AA12013 and AA00284 (MT, JAL); AA11996 (TZ, POB, AA, PM, AMC); AA00233 (KP, CLK); AA07271 (JN, WHG, KCD, JM).

References

- Abbey A. Misperceptions of friendly behavior as sexual interest: A survey of naturally occurring incidents. Psychol Women Q. 1987;11:173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Ross LT. Sexual assault perpetration by college men: The role of alcohol, misperception of sexual intent, and sexual beliefs and experiences. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1998;17:167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Ross LT, McDuffie D, McAuslan P. Alcohol and dating risk factors for sexual assault among college women. Psychol Women Q. 1996;20:147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Brecklin LR, Ullman SE. The role of offender alcohol use in rape attacks: An analysis of National Crime Victimization Survey data. J Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cue KL, George WH, Norris J. Women’s appraisals of sexual assault risk in dating situations. Psychol Women Q. 1996;20:487–504. [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Gournic SJ, McAfee MP. Perceptions of postdrinking female sexuality: Effects of gender, beverage choice, and drink payment. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1988;18:1295–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Hanson K, Layman MJ. A prospective analysis of the relationships among sexual assault experiences. Psychol Women Q. 1995;19:5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP. Hidden rape: Sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of students in higher education. In: Burgess AW, editor. Rape and Sexual Assault II. Garland Publishing; New York: 1988. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC. The relationship of sex-related alcohol expectancies to alcohol consumption and sexual behavior. Br J Addict. 1990;85:919–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb03722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM. Aggression against women: Cultural and individual causes. In: Malamuth NM, Donnerstein E, editors. Pornography and Sexual Aggression. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1984. pp. 19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Martin SE, Bachman R. The contribution of alcohol to the likelihood of completion and severity of injury in rape incidents. Violence Against Women. 1998;4:694–712. [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP, Nichols-Anderson C, Messman-Moore T, Miranda R, Porter C. Alcohol consumption, outcome expectancies, and victimization status among female college students. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30:1056–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenhard CL, Linton MA. Date rape and sexual aggression in dating situations: Incidence and risk factors. J Counsel Psychol. 1987;34:186–196. [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Miller BA, Collins RL, Zetes-Zanatta LM. Women’s descriptions of drinking in bars: Reasons and risks. Sex Roles. 1998;38:701–717. [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Zetes-Zanatta LM. Women’s bar-related victimization: Refining and testing a conceptual model. Aggressive Behav. 1999;25:349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: It’s prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SP, Leonard KE. Alcohol and human physical aggression. In: Geen RG, Donnerstein EI, editors. Aggression: Theoretical and empirical reviews. Vol. 2. Academic Press; New York: 1983. pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA. Qualitative analysis of women’s experiences of sexual aggression: Focus on the role of alcohol. Psychol Women Q. 1999;23:573–589. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Brecklin LR. Alcohol and adult sexual assault in a national sample of women. J Subst Abuse. 2000;11:405–420. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Karabatsos G, Koss MP. Alcohol and sexual aggression in a national sample of college women. J Interpersonal Violence. 1999a;14:603–625. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Karabatsos G, Koss MP. Alcohol and sexual aggression in a national sample of college men. Psychol Women Q. 1999b;23:673–689. [Google Scholar]