Abstract

Objective

There is a paucity of data relating to neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants born late and moderately preterm (LMPT; 32+0–36+6 weeks). This paper present the results of a prospective, population-based study of 2-year outcomes following LMPT birth.

Design

1130 LMPT and 1255 term-born children were recruited at birth. At 2 years corrected age, parents completed a questionnaire to assess neurosensory (vision, hearing, motor) impairments and the Parent Report of Children's Abilities-Revised to identify cognitive impairment. Relative risks for adverse outcomes were adjusted for sex, socio-economic status and small for gestational age, and weighted to account for over-sampling of term-born multiples. Risk factors for cognitive impairment were explored using multivariable analyses.

Results

Parents of 638 (57%) LMPT infants and 765 (62%) controls completed questionnaires. Among LMPT infants, 1.6% had neurosensory impairment compared with 0.3% of controls (RR 4.89, 95% CI 1.07 to 22.25). Cognitive impairments were the most common adverse outcome: LMPT 6.3%; controls 2.4% (RR 2.09, 95% CI 1.19 to 3.64). LMPT infants were at twice the risk for neurodevelopmental disability (RR 2.19, 95% CI 1.27 to 3.75). Independent risk factors for cognitive impairment in LMPT infants were male sex, socio-economic disadvantage, non-white ethnicity, preeclampsia and not receiving breast milk at discharge.

Conclusions

Compared with term-born peers, LMPT infants are at double the risk for neurodevelopmental disability at 2 years of age, with the majority of impairments observed in the cognitive domain. Male sex, socio-economic disadvantage and preeclampsia are independent predictors of low cognitive scores following LMPT birth.

Keywords: Neurodevelopment, Neonatology

What is already known on this topic.

School-aged children born late and moderately preterm are at significantly increased risk for adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes compared with term-born peers.

Large prospective population-based studies of outcomes in infancy are needed.

What this study adds.

Two-year-old children born late and moderately preterm are at double the risk for neurodevelopmental disability compared with term-born peers.

Risk factors for cognitive impairment include male sex, socio-economic disadvantage, non-white ethnic origin, preeclampsia and not receiving breast milk at discharge.

Introduction

Preterm birth rates (<37+0 weeks) have increased significantly in recent decades, largely due to an increase in late (34+0–36+6 weeks) and moderately preterm (32+0–33+6 weeks) deliveries.1 Long-term outcomes for late and moderately preterm (LMPT) infants remain poorly characterised although they account for up to 84% of all preterm births.2 Compared with term-born peers, increasing numbers of reports indicate that children born at late and/or moderately preterm gestations are at increased risk for health and developmental sequelae,3–5 cognitive deficits,6–8 learning difficulties9–13 and behaviour problems8 14 at school age; however, some studies have reported no differences compared with term-born controls.15 16

To allow reliable yet early detection of neurodevelopmental sequelae, assessment at 2 years of age is recommended.17 Reports of neurodevelopmental outcomes during the first 2 years of life are relatively scarce and have produced conflicting results.18 Some have reported an excess of neuromotor, sensory and cognitive impairments in late preterm infants,19–24 while others have found no significant differences after adjustment for confounders or correction for prematurity.21 23 25 Given the paucity of research to date, several authors have asserted that large prospective population-based studies are needed to estimate the long-term impact of LMPT birth.26 27

In this paper we report the results of a prospective population-based study of babies born LMPT compared with term-born controls. The aims of the study were to define neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years corrected age and to explore risk factors for adverse cognitive outcomes in LMPT infants.

Patients and methods

Population

From September 2009 through December 2010 the mothers of all babies born LMPT (32+0–36+6 weeks) within a geographically defined region of the East Midlands (UK) were invited to participate in the Late And Moderately preterm Birth Study (LAMBS). This examined births at four maternity centres, a midwifery-led birthing unit and home births during this period. A random sample of babies born at term (37+0–42+6 weeks) was also recruited during the same time period and in the same geographical region. Eligible term births were selected based on random sampling of dates and times of birth of babies in the same area during the previous year. In addition, mothers of all term-born multiples were invited to participate. Infants with major congenital anomalies were excluded from the present analyses.

Procedure

The study was approved by Derbyshire NHS Research Ethics Committee (Ref 09/H0401/25). Research midwives obtained informed consent from mothers during their postnatal stay; home visits were arranged for mothers discharged shortly after delivery. Mothers participated in a semi-structured interview after birth and obstetric and neonatal data were collected from mothers’ and infants’ medical records at discharge. Follow-up questionnaires were completed at 2 years corrected age.

Measures

Mothers were asked about demographic characteristics including ethnicity and language. To quantify socio-economic status (SES), a composite SES-Index score was computed using five proxy variables that measured mothers’ occupation, education, social support, income and wealth. Total SES-Index scores (range 0–12) were used to define three socio-economic risk categories: low (scores 0–2), moderate (scores 3–5) and high (scores ≥6) (see the online supplementary appendix).

Obstetric data collected included maternal chronic health conditions, smoking and recreational drug use during pregnancy, preeclampsia, maternal infection during pregnancy, pre-labour rupture of membranes, antenatal corticosteroids, induction of labour, mode of delivery, raised C-reactive protein (CRP) during delivery and antenatal umbilical Doppler studies. Neonatal data items included sex, gestation, birth weight, small for gestational age (SGA; fetal weight <3rd percentile for sex and gestation using customised antenatal growth charts28), respiratory support, hypoglycaemia (blood glucose <2 mmol/L), jaundice requiring phototherapy, antibiotic administration, cranial ultrasound and MRI findings, and feeding at discharge.

At 2 years corrected age, cognitive development was assessed using the Parent Report of Children's Abilities-Revised (PARCA-R).29 Scores for non-verbal cognition (NVC; range 0–34) and expressive language (range 0–124) were computed and a total parent report composite (PRC; range 0–158) score derived. PARCA-R scores are strongly correlated with scores on gold standard developmental tests.29–31 To identify moderate/severe cognitive impairment, a cut-off score corresponding with PRC scores <2.5th percentile in the term reference group was identified (PRC score <35). Where children had ≤4 missing NVC items (LMPT, n=40; term, n=44), these were substituted with the child's average NVC item score and the PRC score was computed. For 21 non-English speaking children in whom the language scale was not completed, a NVC score <22 corresponding with NVC scores <2.5th percentile of the term reference group was used to classify impairment. Cognitive impairment was not classified for six children with substantial missing PARCA-R data.

Parents were asked whether their child had non-febrile seizures over the past year and whether s/he was currently taking anticonvulsant medication. Parents were also asked whether their child had a diagnosis of cerebral palsy (CP) and were asked to rate their child's vision, hearing and gross motor function (irrespective of CP); forced-choice answers corresponding with criteria for classifying health status following preterm birth17 were used to identify the severity of impairment (none, mild, moderate, severe) within each domain. Children with a moderate/severe vision (blind/vision uncorrected with aids), hearing (deaf/hearing uncorrected with aids) or gross motor impairment (non-ambulant/requires assistance to walk) were classified with neuromotor/sensory impairment. These were combined with cognitive impairment to provide a composite measure of neurodevelopmental disability defined as moderate/severe impairment in one or more of vision, hearing, gross motor or cognitive function.

Statistical analyses

Baseline socio-demographic characteristics were compared between the term and LMPT groups using percentages (χ2 test) and means (t test) as appropriate. Neurodevelopmental outcomes were compared between term and LMPT infants both crude and with adjustment for major confounders (sex, SES and SGA) using sandwich estimators to account for clustering of outcomes within multiple births. Sampling weights were used to account for the over-sampling of multiple births among the term group. For binary outcomes, differences between groups were quantified using relative risks obtained using Poisson regression. For continuous outcomes, the mean difference (95% CI) between groups was estimated using linear regression models. PARCA-R scores were converted to z scores using the mean (SD) of the term-born reference group to compare effect sizes across scales. Given the high prevalence of cognitive problems, univariable predictors of cognitive impairment were analysed using Poisson regression. A multivariable model was then constructed to identify independent risk factors using sandwich estimators to account for clustering of outcomes within multiple births. Backwards selection was used with all variables in the univariable analyses entered into the model and dropping out the least significant variable until all had p<0.05; all of the dropped variables were then entered in turn into this preliminary model and included if p<0.05.

Results

Population

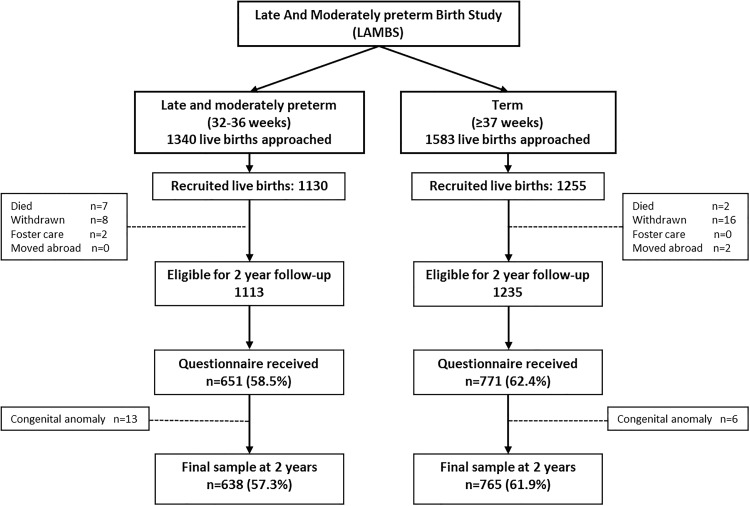

In total, 1130 LMPT and 1255 controls were recruited. Questionnaires were received for 59% of LMPT and 62% of term-born infants. After exclusion of infants with major congenital anomalies, the final sample comprised 638 (57%) LMPT infants and 765 (62%) controls (figure 1). The characteristics of both groups are shown in table 1. Mothers of LMPT infants were significantly more likely to have high socio-economic risk and LMPT infants were more likely to be born SGA (table 1).

Figure 1.

Recruitment, follow-up rates and ascertainment of 2-year outcome data for late and moderately preterm infants and term-born controls.

Table 1.

Baseline socio-demographic characteristics of mothers and their LMPT and term-born infants assessed at 2 years corrected age

| Variable | Term | LMPT | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants, n | 765 | 638 | |

| Gestational age | |||

| Mean (SD), weeks | 39.3 (1.4) | 34.9 (1.2) | – |

| 32–33 weeks, n (%) | – | 87 (13.6%) | – |

| 34–36 weeks, n (%) | – | 551 (86.4%) | – |

| 37–38 weeks, n (%) | 241 (31.5%) | – | – |

| 39–40 weeks, n (%) | 357 (46.7%) | – | – |

| 41–42 weeks, n (%) | 167 (21.8%) | – | – |

| Multiple birth | |||

| n (%) | 151 (19.7) | 107 (16.8) | – |

| Birth weight, g | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3322 (535) | 2435 (502) | – |

| Small for gestational age (SGA)* | |||

| n (%) | 48 (6.3) | 67 (10.5) | 0.004 |

| Male sex | |||

| n (%) | 384 (50.2) | 343 (53.8) | 0.18 |

| Corrected age at assessment | |||

| Mean (SD) | 24.6 (1.1) | 24.6 (1.0) | 0.41 |

| Mothers | N=690 | N=587 | p Value |

| Age | |||

| <20 years, n (%) | 16 (2.3) | 19 (3.2) | 0.56 |

| 20–24 years, n (%) | 96 (13.9) | 86 (14.7) | 0.68 |

| 25–29 years, n (%) | 181 (26.2) | 175 (29.9) | – |

| 30–34 years, n (%) | 209 (30.3) | 192 (32.8) | 0.73 |

| ≥35 years, n (%) | 188 (27.3) | 114 (19.5) | 0.003 |

| Ethnic group | |||

| White, n (%) | 569 (82.5) | 461 (78.5) | – |

| Mixed, n (%) | 7 (1.0) | 12 (2.0) | 0.118 |

| Asian or Asian British, n (%) | 77 (11.2) | 86 (14.7) | 0.057 |

| Black or Black British, n (%) | 30 (4.4) | 21 (3.6) | 0.62 |

| Chinese or other, n (%) | 7 (1.0) | 6 (1.0) | 0.92 |

| Unknown, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | – |

| English not first language | |||

| n (%) | 85 (12.3) | 76 (13.0) | 0.66 |

| SES-Index | |||

| Low risk, n (%) | 339 (49.1) | 256 (43.6) | – |

| Medium risk, n (%) | 209 (30.3) | 184 (31.4) | 0.24 |

| High risk, n (%) | 142 (20.6) | 147 (25.0) | 0.028 |

*SGA classified as fetal weight <3rd percentile for sex and gestation using customised antenatal growth charts.28

SES-Index refers to socio-economic risk category derived from a composite measure of five indices of socio-economic risk (see the online supplementary appendix).

LMPT, late and moderately preterm.

The characteristics of non-responders have been described previously.32 Non-responding mothers were younger, more likely to be non-white, non-English speaking and single parents, to have a lower occupational status and educational qualifications, to be struggling financially and to have poorer health than responders.

Neuromotor and sensory outcomes

LMPT children were at significantly increased risk for neuromotor/sensory impairment (1.6% vs 0.3%; RR 4.89, 95% CI 1.07 to 22.25; table 2). The prevalences of hearing, vision and gross motor impairments were each 0.3–0.5% higher in LMPT infants than in controls and CP was more common in term-born infants (0.5% vs 0%), but the low prevalence of these disorders precluded assessment of the significance of group differences in individual domains. There was no significant excess of seizures or use of anticonvulsant medication in LMPT infants.

Table 2.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years corrected age among late and moderately preterm (LMPT) infants and term-born controls

| Neurodevelopmental outcome | Moderately preterm | Late preterm | All LMPT | Term | Difference LMPT vs term* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=87) | (n=551) | (n=638) | (n=765) | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted† RR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Neurological outcomes | ||||||||

| Seizures, n (%) | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 1.96 (0.17 to 21.61) | 0.58 | – | – |

| Prescribed anticonvulsants, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | 0.49 (0.04 to 5.39) | 0.56 | – | – |

| Neuromotor and sensory impairment | ||||||||

| Cerebral palsy, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (0.5) | – | – | – | – |

| Hearing impairment, n (%) | 0 | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Vision impairment, n (%) | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Gross motor impairment, n (%) | 0 | 5 (0.9) | 5 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 2.44 (0.47 to 12.57) | 0.29 | – | – |

| Neuromotor/sensory impairment‡, n (%) | 0 | 10 (1.8) | 10 (1.6) | 2 (0.3) | 4.89 (1.07 to 22.25) | 0.04 | – | – |

| Cognitive development§ | Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | ||||||

| Non-verbal cognition, mean (SD) | 27.1 (4.3) | 27.6 (4.5) | 27.5 (4.4) | 28.0 (3.4) | −0.59 (−1.03 to −0.13) | 0.01 | −0.49 (−0.94 to −0.03) | 0.04 |

| Expressive language, mean (SD) | 58.9 (32.3) | 61.7 (34.0) | 61.3 (33.7) | 66.4 (31.7) | −5.14 (−8.89 to −1.39) | 0.007 | −3.96 (−7.62 to −0.31) | 0.03 |

| Total PRC score, mean (SD) | 86.0 (34.5) | 89.3 (36.2) | 88.9 (36.0) | 94.5 (33.3) | −5.80 (−9.78 to −1.82) | 0.004 | −4.49 (−8.36 to −0.62) | 0.02 |

| RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |||||||

| Cognitive impairment§, n (%) | 4 (4.7) | 36 (6.6) | 40 (6.3) | 18 (2.4) | 2.66 (1.53 to 4.62) | 0.001 | 2.09 (1.19 to 3.64) | 0.01 |

| Neurodevelopmental disability¶, n (%) | 4 (4.7) | 40 (7.3) | 44 (6.9) | 19 (2.5) | 2.37 (1.38 to 4.08) | 0.002 | 2.19 (1.27 to 3.75) | 0.004 |

*Analyses were weighted to account for over-sampling of term-born multiples.

†Group differences adjusted for sex, SES-Index and SGA.

‡Neuromotor/sensory impairment is classified where a child has a moderate/severe impairment in any one of hearing, vision or motor function.

§Cognitive development was measured using the Parent Report of Children's Abilities-Revised and is defined as a PRC score of <35.

¶Neurodevelopmental disability is defined as a moderate/severe impairment in any one of hearing, vision, motor or cognitive function.

PRC, parent report composite; SGA, small for gestational age.

Cognitive outcomes

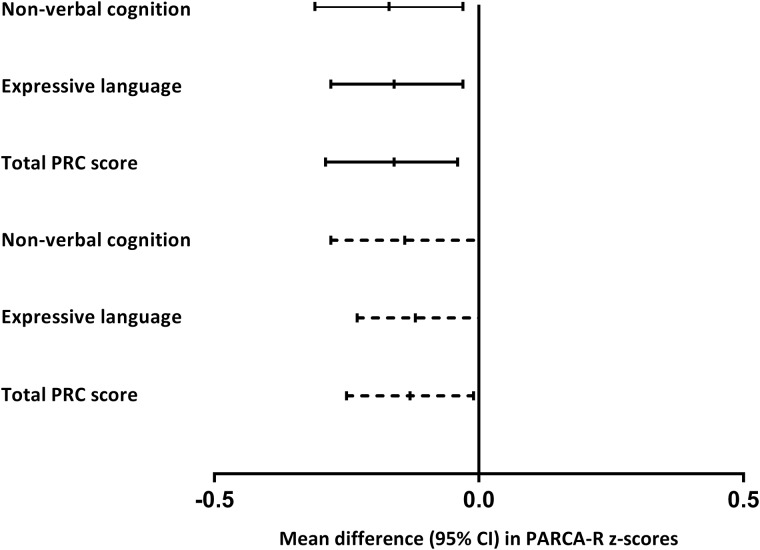

LMPT children had significantly lower mean scores than controls on all PARCA-R scales (table 2), which equated to a 0.14–0.15 SD deficit in both language and non-verbal cognition (figure 2). LMPT infants were significantly more likely to have moderate/severe cognitive impairment than controls (6.3% vs 2.4%; adjusted RR 2.09, 95% CI 1.19 to 3.64). Among LMPT infants, boys were significantly more likely to have moderate/severe impairment than girls (10.5% vs 1.4%; RR 7.77, 95% CI 2.78 to 21.50), but there was no significant sex difference among controls (3.2% vs 1.6%; RR 2.01, 95% CI 0.75 to 5.30).

Figure 2.

Mean difference (95% CI) in Parent Report of Children's Abilities-Revised (PARCA-R) z scores between late and moderately preterm (32–36 weeks gestation) and term-born (37–42 weeks gestation) infants. z Scores were calculated using the mean (SD) of the term reference group. Solid lines represent crude differences and dashed lines represent differences adjusted for sex, socio-economic status and small for gestational age (SGA) status. PRC, parent report composite.

Neurodevelopmental disability

LMPT infants were at significantly increased risk for moderate/severe neurodevelopmental disability (6.9% vs 2.5%; adjusted RR 2.19, 95% CI 1.27 to 3.75; table 2). Of 44 LMPT infants with disability, 40 (91%) had cognitive impairment compared with 18 of 19 (95%) controls with disability.

Risk factors for cognitive impairment in LMPT infants

Univariable analyses revealed that LMPT infants born to mothers aged ≥35 years, of a non-white ethnic origin, with medium or high socio-economic risk, pre-pregnancy hypertension or preeclampsia were more likely to have moderate/severe cognitive impairment (table 3). Of the neonatal factors examined, only male sex, hypothermia (<36°C) and not receiving breast milk at discharge were significantly associated with moderate/severe cognitive impairment. Multivariable regression models identified five independent risk factors for cognitive impairment in LMPT infants (table 3): male sex exerted the greatest effect (RR 7.04, 95% CI 2.52 to 19.67), while high socio-economic risk, non-white ethnic origin, preeclampsia and not receiving breast milk at discharge were also independent predictors.

Table 3.

Associations between demographic, obstetric and neonatal factors and cognitive impairment at 2 years corrected age in LMPT infants

| Variable | Cognitive impairment (n=40) | Univariable analyses | p Value | Multivariable analyses | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstetric/neonatal risk factor present, n (%)‡ | Obstetric/neonatal risk factor absent, n (%)‡ | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |||

| Obstetric risk factors | ||||||

| Mother’s age | ||||||

| <20 years | 1 (5.0) | 39 (6.3) | 1.31 (0.16 to 10.17) | 0.793 | – | – |

| 20–24 years | 8 (9.0) | 32 (5.8) | 2.36 (0.88 to 6.32) | 0.086 | – | – |

| 25–29 years | 7 (3.8) | 33 (7.3) | Baseline | – | – | – |

| 30–34 years | 11 (5.1) | 29 (6.9) | 1.33 (0.52 to 3.37) | 0.544 | – | – |

| 35+ years | 13 (10.4) | 27 (5.3) | 2.73 (1.12 to 6.67) | 0.027 | – | – |

| Non-white ethnic group | 13 (10.1) | 27 (5.4) | 1.88 (1.00 to 3.55) | 0.050 | 2.06 (1.10 to 3.83) | 0.023 |

| Non-English speaking at home | 6 (7.5) | 33 (6.1) | 1.23 (0.53 to 2.84) | 0.632 | – | – |

| SES-Index | ||||||

| Low risk | 8 (2.8) | 32 (9.1) | Baseline | – | – | – |

| Medium risk | 18 (9.2) | 22 (4.8) | 3.26 (1.44 to 7.35) | 0.004 | 2.86 (1.24 to 6.57) | 0.013 |

| High risk | 14 (9.0) | 26 (5.3) | 3.19 (1.36 to 7.43) | 0.007 | 2.36 (1.02 to 5.48) | 0.046 |

| Conceived via infertility treatment | 0 | 40 (6.9) | – | – | – | – |

| Pre-pregnancy diagnosed diabetes | 1 (4.6) | 39 (6.4) | 0.72 (0.10 to 4.99) | 0.735 | – | – |

| Pre-pregnancy diagnosed hypertension | 3 (20.0) | 37 (6.0) | 3.36 (1.16 to 9.69) | 0.025 | – | – |

| Smoked during pregnancy* | 11 (8.6) | 29 (5.7) | 1.50 (0.76 to 2.94) | 0.238 | – | – |

| Drank alcohol during pregnancy† | 18 (6.3) | 22 (6.3) | 1.00 (0.54 to 1.86) | 0.997 | – | – |

| Recreational drugs used during pregnancy‡ | 1 (8.3) | 39 (6.3) | 1.33 (0.22 to 7.86) | 0.750 | – | – |

| Preeclampsia | 12 (12.8) | 28 (5.2) | 2.47 (1.25 to 4.87) | 0.009 | 2.51 (1.33 to 4.70) | 0.004 |

| Infection (+culture) during pregnancy | 1 (11.1) | 39 (6.2) | 1.79 (0.27 to 11.66) | 0.544 | – | – |

| Gestational diabetes | 3 (12.5) | 36 (5.9) | 2.11 (0.71 to 6.26) | 0.176 | – | – |

| Pre-labour rupture of membranes >24 h | 7 (5.7) | 33 (6.5) | 0.88 (0.39 to 1.95) | 0.745 | – | – |

| Antenatal corticosteroids given | 8 (4.6) | 31 (6.8) | 0.68 (0.31 to 1.46) | 0.320 | – | – |

| Labour induced | 9 (6.6) | 30 (6.0) | 1.10 (0.53 to 2.28) | 0.800 | – | – |

| Raised CRP during labour (>5 mg/L) | 1 (4.2) | 38 (6.5) | 0.64 (0.09 to 4.19) | 0.645 | – | – |

| Normal vaginal delivery | 20 (6.2) | 20 (6.4) | 0.98 (0.53 to 1.82) | 0.952 | – | – |

| Absent or reversed end diastolic flow | 2 (7.7) | 38 (6.2) | 1.23 (0.30 to 4.96) | 0.766 | – | – |

| Neonatal risk factors | ||||||

| Male | 36 (10.5) | 4 (1.4) | 7.74 (2.77 to 21.55) | <0.001 | 7.04 (2.52 to 19.67) | <0.001 |

| Gestational age | ||||||

| 36 weeks | 22 (8.0) | 18 (5.0) | Baseline | – | – | – |

| 35 weeks | 6 (3.6) | 34 (7.2) | 0.45 (0.18 to 1.10) | 0.080 | – | – |

| 34 weeks | 8 (7.3) | 32 (6.1) | 0.91 (0.40 to 2.01) | 0.807 | – | – |

| 33 weeks | 3 (6.3) | 37 (6.3) | 0.78 (0.24 to 2.48) | 0.671 | – | – |

| 32 weeks | 1 (2.6) | 39 (6.5) | 0.33 (0.04 to 2.39) | 0.271 | – | – |

| Multiple birth | 4 (3.7) | 36 (6.8) | 0.55 (0.16 to 1.85) | 0.333 | – | – |

| Small for gestational age§ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| >10th centile | 35 (6.2) | 5 (6.8) | Baseline | – | – | – |

| >3rd and ≤10th centile | 2 (5.0) | 38 (6.4) | 0.80 (0.19 to 3.24) | 0.759 | – | – |

| ≤3rd centile | 3 (9.1) | 37 (6.1) | 1.46 (0.47 to 4.55) | 0.511 | – | – |

| Resuscitated at birth | 8 (7.1) | 32 (6.1) | 1.16 (0.54 to 2.43) | 0.702 | – | – |

| Any respiratory support received¶ | 6 (7.1) | 34 (6.2) | 1.14 (0.49 to 2.67) | 0.755 | – | – |

| Intracranial abnormality** | 0 (0) | 40 (6.3) | – | – | – | – |

| Jaundice requiring phototherapy | 2 (4.1) | 36 (6.6) | 0.62 (0.15 to 2.52) | 0.502 | – | – |

| Hypoglycaemia (<2 mmol/L) | 4 (9.3) | 36 (6.1) | 1.53 (0.57 to 4.11) | 0.396 | – | – |

| Hypothermia (<36°C) | 7 (13.0) | 33 (5.7) | 2.29 (1.06 to 4.93) | 0.035 | – | – |

| Antibiotics given | 16 (7.3) | 24 (5.8) | 1.27 (0.68 to 2.34) | 0.445 | – | – |

| Any breast milk at discharge†† | 17 (4.3) | 23 (9.5) | 0.46 (0.24 to 0.84) | 0.011 | 0.52 (0.28 to 0.95) | 0.032 |

Data are shown for all independent variables entered in univariable analyses, and for factors that were significant independent predictors in multivariable analyses.

*Smoked during pregnancy is classified as mothers who smoked at least one cigarette per day at any time during pregnancy versus <1 cigarette per day; data were missing for two mothers.

†Drank alcohol during pregnancy is classified as mothers who drank any alcohol at any time during pregnancy versus no alcohol.

‡Recreational drugs used during pregnancy was classified for one or more instances of drug use at any time during pregnancy.

§Fetal weight for sex and gestation classified using customised fetal growth charts.28

¶Any respiratory support includes infants who were ventilated or received non-invasive respiratory support.

**Intra-cranial abnormality includes grade III or IV intra-ventricular haemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia and grade II or III neonatal encephalopathy.

††Includes breast milk fed by any method. Data were missing for three mothers for gestational diabetes.

‡‡n (%) of infants with cognitive impairment where the obstetric/neonatal risk factor is present (column 2) and absent (column 3).

CRP, C-reactive protein; LMPT, late and moderately preterm.

Discussion

The adverse effects of LMPT birth are already evident at 2 years of age, with LMPT infants having double the risk of neurodevelopmental disability compared with term-born controls. The significant increase in neurodevelopmental disability was almost entirely due to cognitive deficits. Among LMPT infants, mean cognitive and language scores were 0.15 SD lower than among controls, which is equivalent to a 2.3-point deficit in standardised IQ scores. Similar to very preterm infants, this may be indicative of aberrant brain development.33 Substantial neurodevelopment occurs in the third trimester, including a fourfold increase in cortical volume, increased myelination and rapid cerebellar development.34–36 Even at LMPT gestations, preterm birth may impede the normal trajectory of brain development.37

Cognitive deficits of a similar magnitude have been reported in school-aged children born late preterm, although in some studies these differences were not significantly different from controls.6–8 15 16 Comparisons between studies are problematic given the heterogeneity in population characteristics, age at assessment and outcome measures.38 However, Nepomnyaschy et al21 reported that late preterm infants had significantly lower cognitive and language scores at 2 years, but there was a significant group difference only in language after adjustment for confounders. Woythaler and colleagues20 also reported significantly lower cognitive scores at 2 years in the same cohort. In contrast, smaller studies have not found significant group differences at this age, particularly where corrected age has been applied.23 39–41 Since corrected age was used to time assessments in the present study, our findings in terms of both significantly lower mean scores and higher prevalence of impairment are notable. Although the prevalence of neuromotor and sensory impairment was low, rates were 0.3–0.5% higher in the LMPT group. We were unable to assess the significance of group differences in individual domains and the 95% CI for composite neurosensory impairment was wide. However, our results are borne out by the findings of record-linkage studies that have reported a significant excess of neurological sequelae and CP.19 37 42

Few studies have investigated antecedents of adverse outcomes in LMPT infants. In the present study, the strongest risk factor for low cognitive scores was male sex: LMPT boys were at sevenfold increased risk compared with LMPT girls. Among males, LMPT birth conferred a greater risk of moderate/severe impairment compared to controls (10.5% vs 3.2%), while rates among female LMPT infants and controls were similar (1.4% vs 1.6%). The male disadvantage in neurodevelopmental outcomes is well documented in preterm cohorts and the interaction between sex and gestation may explain much of the disadvantage observed here among our LMPT population. As expected, socio-demographic factors were also markers of adverse outcomes; the additive impact of socio-economic factors on long-term outcomes has previously been reported in this population.11 43

Preeclampsia was also identified as an independent risk factor and has been associated with long-term cognitive and behavioural sequelae in general population samples,44–46 and it has been suggested that adverse behavioural outcomes in late preterm infants may be associated with maternal hypertensive disease.47 Worsening symptoms of preeclampsia frequently lead to delivery by induction or caesarean section. In such cases the maternal and fetal risks must be weighed against the long-term effects of prematurity. Further research is needed to disentangle the relative contribution of hypertensive disease and prematurity to long-term outcomes.

It was noted that lack of continuing provision of breast milk at discharge was associated with moderate/severe cognitive impairment. Among extremely preterm infants this has been identified as an independent risk factor for autism and psychiatric disorders.48 49 The mechanisms underlying this association are unclear; the relationship may reflect socio-economic disadvantage, parental aspirations, early attachment, neurological difficulties or a direct role of breast milk in neuronal development.49

Strengths and limitations

The present study addresses the growing need for large, population-based investigations of outcomes following LMPT birth. Data were collected from a birth cohort spanning a wide geographical region of the East Midlands of England and the prospective nature enabled an investigation of risk factors for adverse outcomes including neonatal, antenatal and maternal lifestyle factors. Neurodevelopmental outcomes were classified using standard criteria for defining health status at 2 years17 and contemporaneous reference data were used to define cut-offs for cognitive impairment as recommended in follow-up studies.50 51 Group differences in outcomes were also investigated after adjustment for important confounders.

The major limitation of this study was the response rate at 2 years and the selective dropout of mothers with greater socio-demographic risk. This may have resulted in an underestimation of the true prevalence of adverse outcomes; however, the factors affecting non-response were the same in both groups and thus the relative risks reported are likely to be reflective of the total population. The size of this study necessitated the use of parent questionnaires as outcome measures. Although these may be considered less preferable than developmental tests, well-validated tools were used where possible. In particular, the use of parent reports may have resulted in underestimation of the true prevalence of CP as this may be diagnosed later in childhood, particularly for infants with mild neuromotor signs. Longer term follow-up is needed to determine their prognostic value for later functional outcomes. Despite the sizeable cohort recruited, the study was powered to detect a difference in cognitive impairment between two groups (LMPT vs term). As such, we were unable to assess the statistical significance of group differences in neuromotor and sensory impairments and there was insufficient statistical power to explore a dose–response relationship with gestation age at birth.

Conclusions

Prematurity remains one of the major causes of infant mortality and lifelong morbidity worldwide. We have demonstrated that babies born at 32–36 weeks of gestation are at double the risk for neurodevelopmental disability at 2 years of age, with the vast majority of identified impairments in the cognitive domain. Given the size of the LMPT population, even the small increases in impaired outcomes observed in the present study may have significant long-term public health implications.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SJ, TAE, SES, RM, ESD, DJF, NM, SP and LKS conceptualised and designed the study; SJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript; TAE, SES and RM carried out data analyses; BNM supervised data analyses; and EMB supervised data collection and study progress. All authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding: This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) (Grant Reference Number RP-PG-0407-10029). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. Neil Marlow receives a proportion of funding from the Department of Health's NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme at UCLH/UCL.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Derbyshire NHS REC approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Fuchs K, Gyamfi C. The influence of obstetric practices on late prematurity. Clin Perinatol 2008;35:343–60. 10.1016/j.clp.2008.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Lackritz EM. Epidemiology of late and moderate preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;17:120–5. 10.1016/j.siny.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerstjens JM, de Winter AF, Bocca-Tjeertes IF, et al. Developmental delay in moderately preterm-born children at school entry. J Pediatr 2011;159:92–8. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle EM, Poulsen G, Field DJ, et al. Effects of gestational age at birth on health outcomes at 3 and 5 years of age: population based cohort study. BMJ 2012;344:e896 10.1136/bmj.e896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vrijlandt EJ, Kerstjens JM, Duiverman EJ, et al. Moderately preterm children have more respiratory problems during their first 5 years of life than children born full term. Am J Resp Critical Care Med 2013;187:1234–40. 10.1164/rccm.201211-2070OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poulsen G, Wolke D, Kurinczuk JJ, et al. Gestational age and cognitive ability in early childhood: a population-based cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2013;27:371–9. 10.1111/ppe.12058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cserjesi R, Van Braeckel KN, Butcher PR, et al. Functioning of 7-year-old children born at 32 to 35 weeks’ gestational age. Pediatrics 2012;130:e838–46. 10.1542/peds.2011-2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talge NM, Holzman C, Wang J, et al. Late-preterm birth and its association with cognitive and socioemotional outcomes at 6 years of age. Pediatrics 2010;126:1124–31. 10.1542/peds.2010-1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacKay DF, Smith GC, Dobbie R, et al. Gestational age at delivery and special educational need: retrospective cohort study of 407,503 schoolchildren. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000289 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipkind HS, Slopen ME, Pfeiffer MR, et al. School-age outcomes of late preterm infants in New York City. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:222 e1–6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quigley MA, Poulsen G, Boyle E, et al. Early term and late preterm birth are associated with poorer school performance at age 5 years: a cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012;97:F167–73. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathiasen R, Hansen BM, Andersen AM, et al. Gestational age and basic school achievements: a national follow-up study in Denmark. Pediatrics 2010;126:e1553–61. 10.1542/peds.2009-0829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chyi LJ, Lee HC, Hintz SR, et al. School outcomes of late preterm infants: special needs and challenges for infants born at 32 to 36 weeks gestation. J Pediatr 2008;153:25–31. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potijk MR, de Winter AF, Bos AF, et al. Higher rates of behavioural and emotional problems at preschool age in children born moderately preterm. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:112–17. 10.1136/adc.2011.300131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odd DE, Emond A, Whitelaw A. Long-term cognitive outcomes of infants born moderately and late preterm. Dev Med Child Neurol 2012;54:704–9. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04315.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurka MJ, LoCasale-Crouch J, Blackman JA. Long-term cognition, achievement, socioemotional, and behavioral development of healthy late-preterm infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:525–32. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.British Association of Perinatal Medicine. Report of a BAPM/RCPCH Working Group: classification of health status at 2 years as a perinatal outcome. London: BAPM, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGowan JE, Alerdice FA, Holmes VA, et al. Early childhood development of late-preterm infants: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2011;127:1111–24. 10.1542/peds.2010-2257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrini JR, Dias T, McCormick MC, et al. Increased risk of adverse neurological development for late preterm infants. J Pediatr 2009;154:169–76. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woythaler MA, McCormick MC, Smith VC. Late preterm infants have worse 24-month neurodevelopmental outcomes than term infants. Pediatrics 2011;127:e622–9. 10.1542/peds.2009-3598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nepomnyaschy L, Hegyi T, Ostfeld BM, et al. Developmental outcomes of late-preterm infants at 2 and 4 years. Matern Child Health J 2012;16:1612–24. 10.1007/s10995-011-0853-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron IS, Erickson K, Ahronovich MD, et al. Cognitive deficit in preschoolers born late-preterm. Early Hum Dev 2011;87:115–19. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romeo DM, Di Stefano A, Conversano M, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 12 and 18 months in late preterm infants. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2010; 14:503–7. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baron IS, Weiss BA, Baker R, et al. Subtle adverse effects of late preterm birth: a cautionary note. Neuropsychol 2014;28:11–18. 10.1037/neu0000018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes A, Greisen G, Arce JC, et al. Late preterm birth is associated with short-term morbidity but not with adverse neurodevelopmental and physical outcomes at 1 year. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014;93:109–12. 10.1111/aogs.12258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raju TN, Higgins RD, Stark AR, et al. Optimizing care and outcome for late-preterm (near-term) infants: a summary of the workshop sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pediatrics 2006;118:1207–14. 10.1542/peds.2006-0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samra HA, McGrath JM, Wehbe M. An integrated review of developmental outcomes and late-preterm birth. J Obstetr Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2011;40:399–411. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardosi J, Francis A. Gestation Network. GROW version 5.16.: Gestation Network, 2013.

- 29.Johnson S, Marlow N, Wolke D, et al. Validation of a parent report measure of cognitive development in very preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol 2004;46:389–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson S, Wolke D, Marlow N. Developmental assessment of preterm infants at 2 years: validity of parent reports. Dev Med Child Neurol 2008;50:58–62. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.02010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin AJ, Darlow BA, Salt A, et al. Performance of the Parent Report of Children's Abilities-Revised (PARCA-R) versus the Bayley Scales of Infant Development III. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:955–8. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson S, Seaton SE, Manktelow BN, et al. Telephone interviews and online questionnaires can be used to improve neurodevelopmental follow-up rates. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:219 10.1186/1756-0500-7-219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volpe JJ. Brain injury in premature infants: a complex amalgam of destructive and developmental disturbances. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:110–24. 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70294-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huppi PS, Warfield S, Kikinis R, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of brain development in premature and mature newborns. Ann Neurol 1998;43:224–35. 10.1002/ana.410430213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinney HC. The near-term (late preterm) human brain and risk for periventricular leukomalacia: a review. Semin Perinatol 2006;30:81–8. 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Limperopoulos C, Soul JS, Gauvreau K, et al. Late gestation cerebellar growth is rapid and impeded by premature birth. Pediatrics 2005;115:688–95. 10.1542/peds.2004-1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moster D, Lie RT, Markestad T. Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. N Engl J Med 2008;359:262–73. 10.1056/NEJMoa0706475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Jong M, Verhoeven M, van Baar AL. School outcome, cognitive functioning, and behaviour problems in moderate and late preterm children and adults: a review. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;17:163–9. 10.1016/j.siny.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Darlow BA, Horwood LJ, Wynn-Williams MB, et al. Admissions of all gestations to a regional neonatal unit versus controls: 2-year outcome. J Paediatr Child Health 2009;45:187–93. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2008.01457.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hillemeier MM, Farkas G, Morgan PL, et al. Disparities in the prevalence of cognitive delay: how early do they appear? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009;23:186–98. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.01006.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morag I, Bart O, Raz R, et al. Developmental characteristics of late preterm infants at six and twelve months: a prospective study. Infant Behav Dev 2013;36:451–6. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morse SB, Zheng H, Tang Y, et al. Early school-age outcomes of late preterm infants. Pediatrics 2009;123:e622–e9. 10.1542/peds.2008-1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Potijk MR, Kerstjens JM, Bos AF, et al. Developmental delay in moderately preterm-born children with low socioeconomic status: risks multiply. J Pediatr 2013;163:1289–95. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson M, Oddy WH, Whitehouse AJ, et al. Hypertensive diseases of pregnancy predict parent-reported difficult temperament in infancy. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2013;34:174–80. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31827d5761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitehouse AJ, Robinson M, Newnham JP, et al. Do hypertensive diseases of pregnancy disrupt neurocognitive development in offspring? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012;26:101–8. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson M, Mattes E, Oddy WH, et al. Hypertensive diseases of pregnancy and the development of behavioral problems in childhood and adolescence: the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort Study. J Pediatr 2009;154:218–24. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.07.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Talge NM, Holzman C, Van Egeren LA, et al. Late-preterm birth by delivery circumstance and its association with parent-reported attention problems in childhood. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2012;33:405–15. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182564704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson S, Hollis C, Kochhar P, et al. Psychiatric disorders in extremely preterm children: longitudinal finding at age 11 years in the EPICure study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr 2010;49:453–63.e1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson S, Hollis C, Kochhar P, et al. Autism spectrum disorders in extremely preterm children. J Pediatr 2010;156:525–31. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson S, Wolke D, Marlow N. Outcome monitoring in preterm populations: measures and methods. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie/Journal of Psychology 2008;216:135–46. 10.1027/0044-3409.216.3.135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolke D, Ratschinski G, Ohrt B, et al. The cognitive outcome of very preterm infants may be poorer than often reported: an empirical investigation of how methodological issues make a big difference. Eur J Pediatr 1994;153:906–15. 10.1007/BF01954744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.