Abstract

Biliary strictures can arise from either benign or malignant diseases. Both are amenable to surgical treatment if the surgeon has a clear understanding of the inciting patho-physiology and appropriate training and skill. This review article focuses on the key aspects of surgical management of biliary strictures. The decision to perform a biliary bypass or radical resection of a biliary stricture depends upon the pathology (benign or malignant) and whether there is curative or palliative intent. Endoscopic findings and brushings can often be non-diagnostic and clinical judgment is required. Final pathology ranges from a delayed stricture years following cholecystectomy to cholangiocarcinoma. Performing the correct operation safely requires clinical experience and knowledge of multiple surgical approaches. Surgical options must maximize cure when possible and relieve biliary obstructive and infectious complications.

Keywords: Biliary strictures, Surgical management

Introduction

Biliary strictures can arise from either from benign or malignant diseases. Both are amenable to surgical treatment if the surgeon has a clear understanding of the inciting patho-physiology and appropriate training and skill. The decision to perform a biliary bypass or radical resection of a biliary stricture depends upon the pathology (benign or malignant) and whether there is curative or palliative intent. Endoscopic findings and brushings can often be non-diagnostic and clinical judgment is required (Fig. 1). Final pathology ranges from a delayed stricture years following cholecystectomy to cholangiocarcinoma. Performing the correct operation safely requires clinical experience and knowledge of multiple surgical approaches. Surgical options must maximize cure when possible and relieve biliary obstructive and infectious complications.

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic images can fail to differentiate between a benign and malignant stricture. Brushings can be diagnostic if malignant cells are identified but frequently are non-diagnostic. In the above cases, both underwent resection and reconstruction yet only one harbored a malignancy

Benign Strictures

Benign strictures can result from an inciting stone etiology or a chronic inflammatory disease (Table 1). Primary and secondary common bile duct (CBD) stones can give rise to acute and chronic strictures. Combined endoscopic and laparoscopic techniques can remove and thus treat many stone-related conditions. For acute cholecystitis or secondary CBD stones, laparoscopic cholecystectomy and either surgical or endoscopic management of the CBD stones is often successful [1, 2]. Once a chronic stricture develops, simply removing the inciting CBD stones and or gallbladder is prone to failure and numerous procedures such as dilatation and stenting are likely to be required [3, 4]. The clinician must evaluate the acute or chronic nature of a stricture and determine the optimal treatment; stone removal alone or bile duct reconstruction. In certain circumstances, a trial of endoscopic drainage and time will enable the team to determine whether definitive treatment is required for a chronic stricture [1, 3]. Prior to embarking on a definitive reconstruction of a biliary stricture, all acute infectious and obstructive symptoms should be resolved. The necessary preoperative images should be obtained and the obstructive and infectious complications addressed prior to definitive surgical intervention.

Table 1.

Causes of biliary strictures

| Biliary stone causes |

| 1. Choledocholithiasis resulting in recurrent cholangitis and stricture |

| 2. Mirizzi’s syndrome or stone impaction at the cystic duct and CBD |

| 3. Stenosis of sphincter of Oddi secondary repeat passage of gallstones |

| Inflammatory causes |

| 1. Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

| 2. Choledochal cysts resulting in chronic biliary mucosal damage |

| 3. Recurrent or severe pancreatitis |

| 4. Parasitic infection |

| 5. Radiation injury |

| 6. Peptic ulcer diseases and duodenal diverticular diseases |

| Surgical injury |

| 1. Ischemic biliary strictures from devascularization of CBD during cholecystectomy |

| 2. Biliary reconstruction in setting of small ducts or acute injury/inflammation |

| 3. Gastric, duodenal, pancreatic and hepatic surgery |

| Malignant causes |

| 1. Cholangiocarcinoma or bile duct adenocarcinoma |

| 2. Gallbladder carcinoma due to extrinsic compression or direct extension |

There are situations that are likely to require a definitive operative approach. Mirrizzi’s syndrome, stone impacted in the cystic duct common duct junction, can permanently distort and stricture the mid duct and require surgical management (Fig. 2). Since the inciting stone does not reside in the common bile duct lumen, endoscopic extraction is technically difficult but not impossible [1, 3]. The degree of chronic inflammation and anatomic distortion of the surgical landmarks makes laparoscopic surgery challenging and at times dangerous [2, 3, 5, 6]. The degree of CBD injury and scarring dictates which surgical procedure should be utilized, which can range from subtotal cholecystectomy to hepaticojejunostomy [7]. Although rare, primary common bile duct stones require surgical management for lasting relief. By definition, a primary CBD stone is formed within the extra- or intra-hepatic biliary system and associated with black or brown pigment stones, stasis and chronic infection. Definitive management must include wide drainage of the biliary system typically through either a choledochoduodenostomy or Roux en Y hepaticojejunostomy [8]. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) provides temporizing treatment and provides anatomic detail for surgical planning but is seldom effective in preventing recurrent stone formation (Fig. 3). Finally, repetitive attacks of pancreatitis (gallstone, alcohol, or familial) can permanently damage the distal bile duct. The resulting chronic stricture will require lifelong endoscopic management or surgical bypass procedure.

Fig. 2.

Mirrizi’s syndrome can cause the common bile duct to narrow and obstruct. Stone within the gallbladder is outlined by arrows yet the CBD cystic duct junction is distorted. Endoscopic stone extraction may prove impossible as the stone is extrinsic to the accessible common bile duct. In this case an open cholecystectomy and stone extraction was required

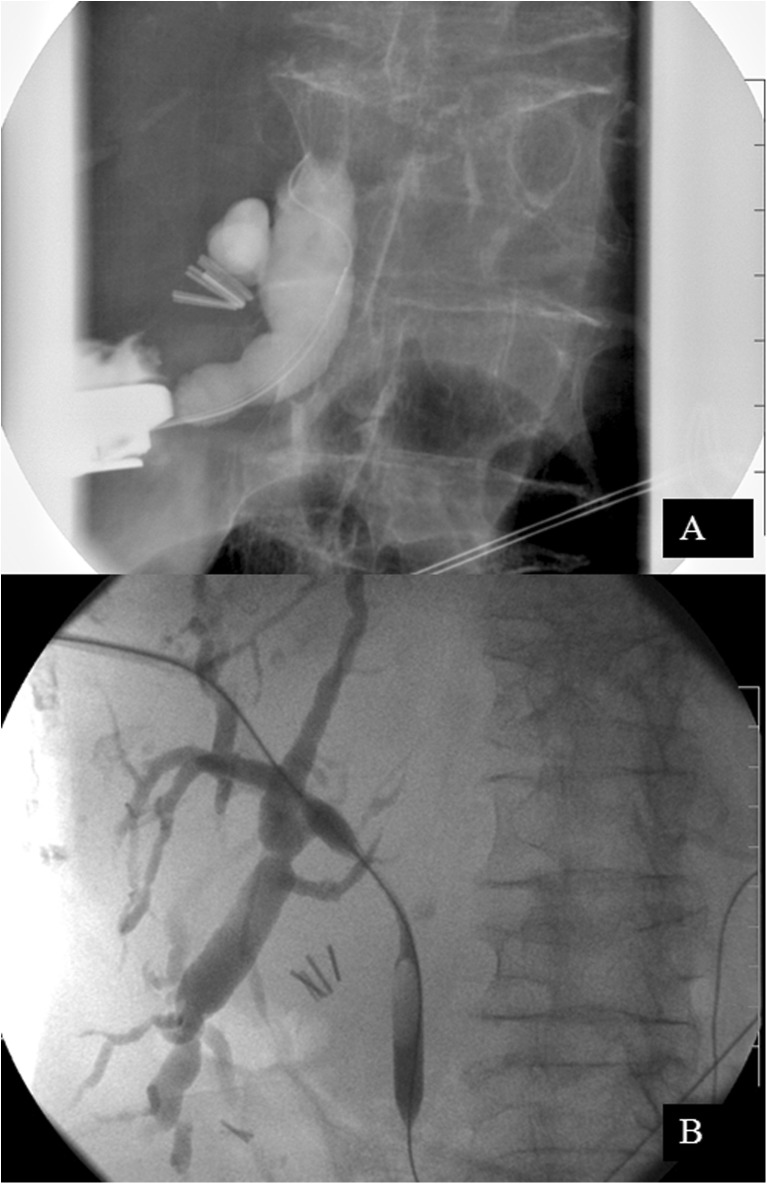

Fig. 3.

Common bile duct stones can form within the CBD, note previous cholecystectomy clips. Extensive, primary CBD stone burden proved refractory to multiple ERCP attempts. This patient underwent a CBD exploration and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy; alternatively, a choledochoduodenostomy could have been performed

Other less common inflammatory diseases can create strictures of the CBD and include primary sclerosing cholangitis and choledochal cysts. These two conditions are considered pre-malignant and resection over bypass is advocated when feasible. The goal of resection is to reduce the risk of a future malignancy and provide lasting relief of obstructive symptoms [9, 10]. Optimal timing of surgery and choosing the most appropriate procedure for a biliary stricture requires clinical judgment and appropriate surgical training.

Unfortunately, benign strictures are occasionally the direct result of a surgical injury to the CBD. Prior to the advent of the laparoscopic cholecystectomy, open major bile duct injuries and iatrogenic strictures following surgery occurred infrequently ranging from 0.04 to 0.13 % [11, 12]. A temporary rise in the pattern and frequency of these injuries was seen in the early laparoscopic experience which was attributed to the learning curve until stabilizing at 0.11 to 0.30 % [11, 12]. Risk factors associated with major bile duct injuries included: male sex, teaching hospital, pancreatitis/obstructive jaundice/cholangitis and acute cholecystitis [12]. Surgical adjuncts such as early conversion to open technique and liberal use of intra-operative cholangiograms still failed to prevent some injuries [12, 13]. Theoretically any surgical procedure involving the gallbladder, CBD or even surrounding organs can lead to a bile duct injury or stricture. Surgical maneuvers to avoid these injuries include: obtaining clear field of view of the surgical field, identifying all anatomy carefully and recognizing common anomalies.

Iatrogenic bile duct injuries may be recognized at surgery, can present in the early postoperative period or present late as a CBD stricture. The presentation (early or delayed) the status of the patient (stable or unstable) and the location of the injury (high or low) dictate the surgical procedure required for management [14]. Early iatrogenic bile duct injuries present with bile peritonitis manifest by acute abdominal pain, tachycardia, and can progress to a septic picture rapidly if the intra-peritoneal bile flow is not controlled. Liver function tests may be completely normal even in the face of a significant injury and cannot be used as a screening tool. Early recognition, prompt evaluation and drainage or repair of the ongoing bile leak is required. Delayed bile duct injuries present as biliary strictures months to years after the index surgery. The patient presents with jaundice, abnormal liver function test, or biliary cirrhosis. These delayed injuries are most commonly the result of devascularization of the peri-ductal blood supply. The delayed presentation and subtle clinical symptoms allows for more elective workup and referral. Reconstruction results are excellent is skilled hands [4, 14, 15].

The Stewart-Way classification was created to describe the various patterns of injury and assist with choice of treatment [13]. Properly identifying the site of injury and proximal and distal components of the biliary tree are essential [4, 14]. The technique utilized to obtain a complete cholangiogram may vary and include multiple techniques: ERCP, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) or intra-operative cholangiogram (Fig. 4). A delayed stricture often presents with abnormal liver function tests or non-specific abdominal complaints. The gastroenterologist may choose to obtain an ERCP or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography to better define the anatomy. Prompt recognition and resumption of biliary drainage must be accomplished before biliary cirrhosis develops.

Fig. 4.

High bile duct injury (Stewart-Way Class III) following a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. PTC was unable to access the normal sized bile ducts. Diagnostic laparoscopy with intra-operative cholangiogram identified a high injury to left (a), right anterior (segment V and VIII) (b) and (posterior segments VI and VII) (c) ducts. This patient required a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy incorporating all three hepatic ducts

The medicolegal issues surrounding iatrogenic bile duct injuries are particularly powerful. The surgeon who injures the bile duct seldom recognizes the surgical error and is often unable to recognize the presenting signs and symptoms [13]. Consultation with an experienced hepato-biliary surgeon is prudent when tackling these difficult and litigious situations [4, 13, 14]. In order to ensure lasting results, the surgeon must interrogate the biliary tree completely, select the correct surgical reconstruction and optimize the patient for surgery.

Malignant biliary strictures are most commonly due to pancreatic and primary biliary neoplasms. Primary extra-hepatic biliary neoplasm or cholangiocarcinoma often present with clinical jaundice but unfortunately nodal and hepatic metastases often exclude curative options. Pancreatic head adenocarcinoma can infiltrate or mechanically obstruct the CBD and is most commonly treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy with curative intent. Despite aggressive surgery, long-term survival remains poor. Currently, non-surgical means of palliation, ERCP or PTC, should be attempted when there is no curative intent (Fig. 5). Surgical palliation is effective, but in this author’s opinion, is only indicated when minimally invasive techniques fail. The role of endoscopic and surgical palliation remains an active debate in the literature. A more common scenario for surgical palliation occurs when unrecognized metastatic disease is found at laparotomy; for example, at planned pancreaticoduodenectomy. Palliative surgical procedures must achieve adequate biliary drainage and prevent infections complications of the obstructed biliary tract. A poorly planned or improperly executed surgical bypass may worsen the patient’s quality of life and prevent future minimally invasive (ERCP and PTC) options.

Fig. 5.

Malignant stricture refractory to endoscopic drainage and stenting (a). Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram (PTC) decompressed the biliary system and palliated jaundice effectively (b)

Radical surgery is employed when a malignant biliary stricture is resectable with curative intent. The surgical procedures required to treat these diseases are beyond the scope of this review. Because of where these tumors arise, there is only limited space between the tumor and portal vein and hepatic artery (posterior margin), pancreas (inferior margin) and liver (superior margin). To increase tumor margins, combined en bloc pancreaticoduodectomy and/or hepatetomy have been added to radical resectional procedures. Unfortunately even in skilled hands, surgical morbidity and mortality remain high. Careful planning and patient counseling will ensure that both the surgeon and patient are prepared to undertake the necessary steps to optimize cure. The curative treatment of a malignant biliary stricture is an extensive and specialized surgical operation that should be practiced at high volume hepato-biliary centers.

Surgical Procedures

Cholecystectomy with Bile Duct Exploration and T-Tube Drainage

A biliary narrowing arising from stone etiology can be treated very effectively by removing the source of stone burden (gallbladder) and any stones in the CBD. Providing temporary drainage utilizing a T-tube or PTC will allow biliary decompression and access while the tissues heal. The gallbladder dissection facilitates the identification of the cystic duct and CBD junction. A transcystic dilatation or a direct choledochotomy can be utilized to gain access to the lumen of the CBD. Stones can be manually (open cases only) palpated, visually identified via a choleductoscopy (Fig. 6) or fluoroscopy. Stone extraction usually requires a combination of all of these modalities. Prior experience in the procedure and knowledge of the surgical tools is clearly beneficial (Fig. 7). Today, preoperative and or postoperative ERCP for CBD stones is practiced widely in making surgical CBD explorations a vanishing operation. In fact, the number of operative CBD explorations (open or laparoscopic) was 1.7 (mean) per chief resident graduating in 2005 [16] and declined from 9.7 in 1988 to 0.3 in 2008 [17]. Unfortunately, surgeons trained in past decades, may lack the training and experience needed to perform a successful and safe CBD exploration.

Fig. 6.

Common bile duct exploration is done via vertical choledochotomy. Sutures elevate and separate the duct wall while stone material is carefully removed. Choledochoscopy and fluoroscopy are required to ensure that stone material is retrieved from above and below the ductotomy. T-tube placement provides drainage and access for future cholangiograms

Fig. 7.

Common tools utilized to access and extract stones within the CBD: Bakes dilators and curved stone graspers (above) and flexible choledochoscope with working tools (below). Disposable wires, balloons and baskets are often required (not shown)

Mirizzi’s syndrome or cholecystobiliary fistula creates a situation where scarring and distortion of the anatomy places the CBD in danger of surgical injury. Laparoscopic attempts at treating Mirrizzi syndrome have been reported in the literature but these are highly selected cases performed by skilled and experienced hands [1, 6]. The open technique will provide better visualization of anatomy and should be advocated for the less experienced surgeon. The degree of CBD injury and scarring will dictate which surgical procedure should be utilized. For minimal CBD involvement, a subtotal cholecystectomy with stone extraction and drainage will suffice. A subtotal cholecystectomy is done by leaving a portion of the gallbladder in place to avoid undue risk to the scarred CBD. When the anatomy is distorted or the CBD edges appear poorly suited for re-approximation a biliary-enteric anastomosis should be performed (described below).

Transduodenal Sphincteroplasty

The transduodenal sphincteroplasty procedure is similar to an endoscopic sphincteroplasty in that it divides the sphincter musculature and provides wide drainage of the ampulla of Vater. The technique is indicated for distal impacted stones, chronic strictures or recurrent biliary pancreatitis resulting from a long common channel that is refractory to endoscopic management. The technique is most commonly done using an open technique with complete duodenal mobilization or Kocher maneuver. A longitudinal opening in the duodenal wall directly adjacent to the ampulla will ensure optimal visualization. Placing a Fogarty catheter or Bake’s dilator through the CBD or cystic duct down into the duodenum will enable the surgeon to locate the ampulla. Once the sphincter is identified, a needle tip cautery can be utilized to open the muscular sphincters at the 12 o’clock position. Small absorbable interrupted sutures will secure the mucosal layers to the widely opened channel. The sphincterotomy length is limited to the region where the duodenum and CBD share a common wall in order to prevent retroperitoneal or peritoneal leakage. A small probe may be utilized to identify the pancreatic duct and ensure that the sphincterotomy provides adequate pancreatic drainage. Primary repair of the duodenotomy can be done in a tension free manner without resulting in lumen narrowing. This technique has almost disappeared in the surgical armamentarium due to the success of the endoscopic procedure. In 1988, surgical residents performed on average only 1.0 surgical sphinteroplasty (of Oddi) procedure in training, this number has declined to 0.1 in 2008 [16]. Surgeons in training today are likely never to see this procedure and knowledge of the steps involved and subtle nuances are likely to be lost in the future.

Choledochoduodenostomy

The choledochoduodenostomy procedure bypasses the distal bile duct completely and can be successfully utilized for a distal impacted CBD stone or stricture and to palliate a distal malignant stricture. The open technique with an upper midline or subcostal incision is typically required. Extensive mobilization of the bile duct is not needed; instead the duodenum should be fully mobilized to ensure a tension free anastomois. A longitudinal choledochotomy is performed sharply and extended to a length adequate for a complete CBD exploration (at least 2 cm). A duodenotomy is placed adjacent to the choledochotomy of similar length and the anastomosis is completed with absorbable suture. In the setting of an unresectable malignancy, most surgeons avoid this technique and advocate using the Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (see below) to avoid complications related to future duodenal obstruction by the tumor. As with all complex surgical biliary procedures, the choledochoduodenostomy is seldom performed and seldom taught to graduating residents.

Roux-en-Y Hepaticojejunostomy

The Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy is the most versatile and most practiced form of biliary reconstruction and can be utilized to bypass benign or malignant diseases or reconstruct the biliary drainage after radical resection. This reconstruction is safe and effective at managing laparoscopic CBD injuries to include early transections and delayed strictures. Preparation for the Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy begins with delineating the anatomy. Careful review of operative dictations and intra-operative cholangiograms is critical. ERCP and PTC can be used selectively to ascertain the proximal and distal extent of the injury. Liberal use of intra-operative imaging should be obtained to ensure that all biliary radicals are adequately drained. The surgical procedure is most commonly done open though either a subcostal or upper midline incision. The hilar plate is lowered to improve visualization and suture placement. Then the distal or injured segment is isolated taking care to avoid injury to the portal vein and hepatic arteries. Anomalous and distorted anatomy is common so care must be taken not to devascularize blood supply to the hepatic duct and liver. The CBD is divided distally toward the pancreas and over sewn to prevent reflux and leakage of pancreatic enzymes. Careful dissection toward the liver hilum is performed ensuring two critical aspects. One, that there is adequate blood supply to the section of the now hepatic duct to be used for reconstruction. Two, length of healthy hepatic ducts are preserved to prevent the need for multiple anastomosis of sub-segmental bile ducts. A Roux-en-Y is made of healthy jejunum distal to the ligament of Treitz and passed typically through the transverse mesocolon to the hilum of the liver. The limb should be well vascularized and tension free. An end to side anastomosis is created using fine absorbable interrupted suture (Fig. 8). The use and choice of stents varies by surgeon. Historically the Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy provides the most successful and most durable repair with an 80 to 99 % success rate in skilled hands [4].

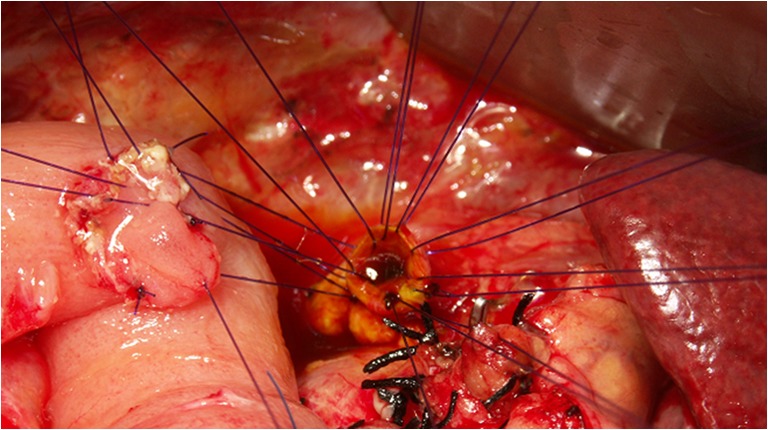

Fig. 8.

Intra-operative photo of a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy: hepatic duct at the hilum (right) is sutured to a tension free loop of jejunum (left)

The Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy is utilized for reconstruction after radical resection of nearly all forms of biliary and pancreatic cancer head resection. There is wide variation in organs resected between a hilar cholangiocarcioma and a pancreatic head adenocarcinoma yet the reconstruction for each is almost identical. This reconstruction is also utilized in liver transplants and the Kasai procedure. For this reason, surgeons in training will perform a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy several times and under guidance of a variety of surgeons, surgical oncologists, transplant and pediatric surgeons. This technique, although arguably the most invasive, may be the safest and most practiced in this era of minimally invasive biliary options. Table 2 summarizes the pros and cons of individual surgical technique and Table 3 summarizes the surgical options specific to individual pathology.

Table 2.

Pros and cons of individual surgical technique

| Technique | Pro | Con |

|---|---|---|

| Cholecystectomy with bile duct exploration and T-tube drainage | • Technically simple | • Requires skills seldom taught to surgical residents |

| • Can be performed using open and laparoscopic access (in skilled hands) | • Requires multiple biliary tools and instruments | |

| • Effective when stone-related inflammation is acute | • Ineffective with chronic strictures | |

| Transduodenal sphincteroplasty | • Used when ERCP ineffective or ampulla inaccessible | • Requires skills seldom taught to surgical residents |

| • Limited indications | ||

| Choledochoduodenostomy | • Simple technique for direct widely patent biliary drainage | • Requires skills seldom taught to surgical residents |

| • Effective for chronic distal benign strictures or impacted stones | • Limited indications | |

| Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy | • Best understood and taught surgical procedure | • Most complex reconstruction |

| • Effective and versatile | • Requires division and reconstruction of jejunum | |

| • Broad indications |

Table 3.

Surgical options specific to pathology

| Pathology | Surgical options | Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Acute choledocholithiasis | Cholecystectomy with bile duct exploration and T-tube drainage | Cholecystectomy with ERCP |

| Stone impaction at ampulla | Cholecystectomy with bile duct exploration and T-tube drainage | Transduodenal sphincteroplasty |

| Mirizzi’s syndrome | Cholecystectomy with bile duct exploration and T-tube drainage | Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

| Stenosis of sphincter of Oddi | Transduodenal sphincteroplasty | Choledochoduodenostomy or Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

| Gallstone pancreatitis (primary stones and common channel) | Transduodenal sphincteroplasty | Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

| Chronic pancreatitis with obstructed jaundice (benign) | Choledochoduodenostomy | Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

| Ischemic biliary strictures | Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy | |

| Primay sclerosing cholangitis | Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy | |

| Choledochal cysts | Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | Radical resection with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy | Palliative Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | Radical resection with roux-en-y hepaticojejunostomy | Palliative Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | Radical resection with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy | Palliative Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

Conclusion

The surgical management of biliary pathology has undergone a rapid decline in past 20 years. The less invasive endoscopic tools, due to their success, have relegated surgery to only the most difficult situations. When the surgeon is called upon to manage biliary pathology, there is an imbalance between training and experience and degree of technical difficulty. In the future select biliary procedures, including some described in this article, may be relegated to surgeon specializing in the hepato-biliary field and surgical texts. Fortunately, due to the relative simplicity of the CBD exploration and drainage, surgeons will continue to practice this in most major medical centers. The Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy due its wide utility and broad applications across many surgical fields will continue to be taught and practiced. Newly trained surgeons are likely to be comfortable and experienced in this technique. Using just the CBD exploration and the Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, the great majority of biliary pathology can be safely managed by well-trained surgeons.

References

- 1.Qin M, Xu H. Combined laparoscopic and endoscopic treatment for bile duct diseases. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Dis Int. 2004;3(2):284–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pemberton M, Wells AD. The Mirizzi syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73(862):487–490. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.73.862.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.England RE, Martin DF. Endoscopic management of Mirizzi’s syndrome. Gut. 1997;40(2):272–276. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.2.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart L. Treatment strategies for benign bile duct injury and biliary stricture. In: Poston GJ, Blumgart LH, editors. Surgical management of hepatobiliary and pancreatic disorders. London: Martin Dunitz; 2003. pp. 315–329. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowbey PK, Sharma A, Mann V, Khullar R, Baijal M, Vashistha A. The management of Mirizzi syndrome in the laparoscopic era. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2000;10(1):11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohatgi A, Singh KK. Mirizzi syndrome: laparoscopic management by subtotal cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc Interv Technol. 2006;20(9):1477–1481. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0623-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Csendes A, Diaz JC, Burdiles P, Maluenda F, Nava O. Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystobiliary fistula: a unifying classification. Br J Surg. 1989;76(11):1139–1143. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800761110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shojaiefard A, Esmaeilzadeh M, Ghafouri A, Mehrabi A. Various techniques for the surgical treatment of common bile duct stones: a meta review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2009;2009:840208. doi: 10.1155/2009/840208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singham J, Yoshida EM, Scudamore CH. Choledochal cysts part 3 of 3: management. Can J Surg. 2010;53(1):51–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai S, Pawlik TM. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: the role of extrahepatic biliary resection. Adv Surg. 2009;43(1):175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell JC, Walsh SJ, Mattie AS, Lynch JT. Bile duct injuries, 1989–1993: a statewide experience. Arch Surg. 1996;131(4):382–388. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430160040007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fletcher DR, Hobbs MST, Tan P, Valinsky LJ, Hockey RL, Pikora TJ, Knuiman MW, Sheiner HJ, Edis A. Complications of cholecystectomy: risks of the laparoscopic approach and protective effects of operative cholangiography: a population-based study. Ann Surg. 1999;229(4):449–457. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199904000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Way LW, Stewart L, Gantert W, Liu K, Lee CM, Whang K, Hunter JG. Causes and prevention of laparoscopic bile duct injuries: analysis of 252 cases from a human factors and cognitive psychology perspective. Ann Surg. 2003;237(4):460–469. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000060680.92690.E9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sicklick JK, Camp MS, Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Yeo CJ, Campbell KA, Talamini MA, Pitt HA, Coleman J, Sauter PA, Cameron JL, Vickers SM, Adams RB, Gaber AO, Gadacz TR, Cofer JB. Surgical management of bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: perioperotive results in 200 patients. Ann Surg. 2005;241(5):786–795. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161029.27410.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nealon WH, Urrutia F. Long-term follow-up after bilioenteric anastomosis for benign bile duct stricture. Ann Surg. 1996;223(6):639–648. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199606000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell RH, Biester TW, Tabuenca A, Rhodes RS, Cofer JB, Britt LD, Lewis FR. Operative experience of residents in US general surgery programs: a gap between expectation and experience. Ann Surg. 2009;249(5):719–724. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a38e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung RS, Ahmed N. The impact of minimally invasive surgery on residents’ open operative experience: analysis of two decades of national data. Ann Surg. 2010;251(2):205–212. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c1b18e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]