Abstract

The application of cervical esophagogastric anastomoses was of great concern. However, between circular stapler (CS) and hand-sewn (HS) methods with anastomosis in the neck, which one has better postoperative effects still puzzles surgeons. This study aims to systematically evaluate the effectiveness, security, practicality, and applicability of CS compared with the HS method for the esophagogastric anastomosis after esophageal resection. A systematic literature search, as well as other additional resources, was performed which was completed in January 2013. The relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) about the surgical technique for esophageal resection were included. Trial data was reviewed and extracted independently by two reviewers. The quality of the included studies was assessed by the recommended standards basing on Cochrane handbook 5.1.0, and the data was analyzed via RevMan 5 software (version 5.2.0). Nine studies with 870 patients were included. The results showed that in comparing HS to CS methods with cervical anastomosis, no significant differences were found in the risk of developing anastomotic leakages (relative risk (RR) = 1.30, 95 % confidence intervals (CI) 0.87–1.92, p = 0.20), as well as the anastomosis stricture (RR = 0.97, 95 % CI 0.47–1.99, p = 0.93), postoperative mortality (RR = 0.83, 95 % CI 0.43–1.58, p = 0.57), blood loss (mean difference (MD) = 39.68; 95 % CI −6.97, 86.33; p = 0.10) and operative time (MD = 18.05; 95 % CI −3.22, 39.33; p = 0.10). However, the results also illustrated that the CS methods with cervical anastomosis might be less time-consuming and have shorter hospital stay and higher costs. Based upon this meta-analysis, there were no differences in the postoperative outcomes between HS and CS techniques. And the ideal technique of cervical esophagogastric anastomosis following esophagectomy remains under controversy.

Keywords: Circular stapler, Hand-sewn, Esophagectomy, Cervical anastomosis, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

As esophageal cancer is the eighth most common malignancy around the world [1], the mortality of esophageal cancer in China is the highest around the world according to the WHO [2, 3]. Staple with a circular stapler (CS) is regarded as a safe alternative to manual suturing in colonic, rectal [4], and gastric anastomosis [5], as well as esophagogastric anastomosis [6]. With the development of surgical techniques, many advances have been applied to the surgery of esophageal cancer in the past decade [7, 8]. Although lower rate of mortality has always been reported [9–11], the postoperative complications are proven to be frequently common, which included anastomotic leakage and stricture. Among the factors leading to the higher mortality, anastomotic leakage plays an essential role, with the rate ranging from 0 to 41 % [12]. So, which modality surgeons should adopt is a question.

Recently, using a gastric tube for reconstruction after esophagectomy has been of great concern. Disagreement still exists, and they often focus on the technical modality of anastomosis, such as the hand-sewn or stapled methods [13, 14]. Compared with the hand-sewn (HS) method, the results from published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that CS was considered to reduce the incidence of operative complications [15, 16], but with a higher chance of anastomotic stricture [17, 18].

Both HS and CS in cervical esophagogastrostomy are widely accepted procedure [19–21]. However, some debates still exist. Several previous systematic reviews on this topic [6, 22–24] concluded that the evidence was weak due to the clinical heterogeneity, such as different sites (cervical vs thoracic) and configurations (end to end vs end to side), which could not be strong enough to guide the clinical applications. The controversy concerning on cervical esophagogastric anastomoses was more obvious [6, 25]. To date, there were no systematic reviews or meta-analyses of the literature only focusing on cervical anastomosis (HS vs CS). Hence, in order to assess the comparison between HS and CS methods with cervical anastomoses, it is necessary and vital to carry out a meta-analysis on the basis of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) [26], as well as grade the quality of overall evidence on outcomes by the The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [27].

Methods

Literature Search

All relevant RCTs were included irrespective of blinding, sample size of patients randomized, or languages. The following electronic databases were searched limitedly from their inception to January 2013, which included PubMed, EMBASE, ISI Web of Knowledge, the Cochrane Library, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), Chinese Journal Full-text Database (CNKI), Chinese Science and Technology Periodicals Database (VIP), and WangFang database.

By using medical subject headings (MeSH) terms combined with free text terms, the search items were as follows: esophageal carcinoma, esophagogastomy, anastomosis, esophagogastric anastomosis, oesophagogastric anastomosis, leakage, cervical, hand-sewn, manual, staple, mechanical, etc.

We performed an additional search to Google Scholar. All search strategies were determined eventually after numerous pre-searches.

Study Selection

The duplicates were removed using EndNote X5 software. The reviews, comments, letters, and case reports were excluded after screening initially the titles and abstracts. Finally, the eligible trials were identified through reading the full text. Only when agreed by both of two reviewers would one trial be included in this study. Disagreements were resolved through discussions. When faced with studies reported by the same institution or the same authors from one trial, the one with higher quality or latest publication would be included.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted the following data: titles, years of publication, country and district, years of study, study design, interventions, no. of patients and their characteristics, methodological quality, and primary and secondary outcomes.

The primary outcomes were as follows: anastomotic leakage ((1) egress through the drains of intestinal fluids or orally ingested methylene blue, (2) sodium diatrizoate swallow performed either routinely between days 3 and 8 or because of signs of leakage, or (3) repeat operation or autopsy); anastomotic strictures (within 180 days through endoscopy); and postoperative mortality (within 30 days after operation).

The secondary outcomes were as follows: operative time (minutes), blood loss (milliliters), time of anastomosis (minutes), hospital stay (days), and the costs.

Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion

We included these studies into meta-analysis if they met all the following inclusion criteria:

The RCTs irrespective of blinding used or not

Hand-sewn versus stapled esophagogastric anastomosis in the neck

The patients were undergoing esophagogastomy.

The following are the exclusion criteria:

The studies were conducted in children (less than 18 years old).

Patients with serious internal organs diseases or infection diseases

Assessment of Methodological Quality of Included Studies

According to the criteria stated in The Cochrane Collaboration Handbook, the quality items assessed were sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. We assigned a label of “yes,” “unclear,” or “no” to estimate risk of bias, and each study was signed three quality grades including A (low risk of bias), B (moderate risk of bias), and C (high risk of bias). The results would be presented in both a graph of risk of bias and a summary section of risk of bias.

All main outcomes were performed through using GRADEpro (http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/other-resources/gradepro, version 3.6) [28]. As is known, RCTs are regarded as high-quality evidence unless they are limited by serious defects of bias due to the impact on study quality, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecise or sparse data, or high probability of reporting bias [29]. If any of the items mentioned above existed, the rating quality of evidence grade could be downgraded to moderate, low, or very low [30].

Statistical Methods

The statistical analysis was performed, and the forest plots were generated using the Review Manager 5 (version 5.2.0) software. The relative risk (RR) was calculated along with its 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for binary outcomes and mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes. Statistical heterogeneity between studies was assessed by means of chi-square, and the extent of inconsistency was assessed by the I2 statistic [30]. If I2 < 50 %, we used the fixed-effects model, and the random-effects model was chosen with I2 > 50 %. Descriptive techniques were used when clinical heterogeneity existed and also when no data could be used in statistical analysis. The stability of outcomes was tested by sensitivity analysis if necessary.

Results

Selected Studies

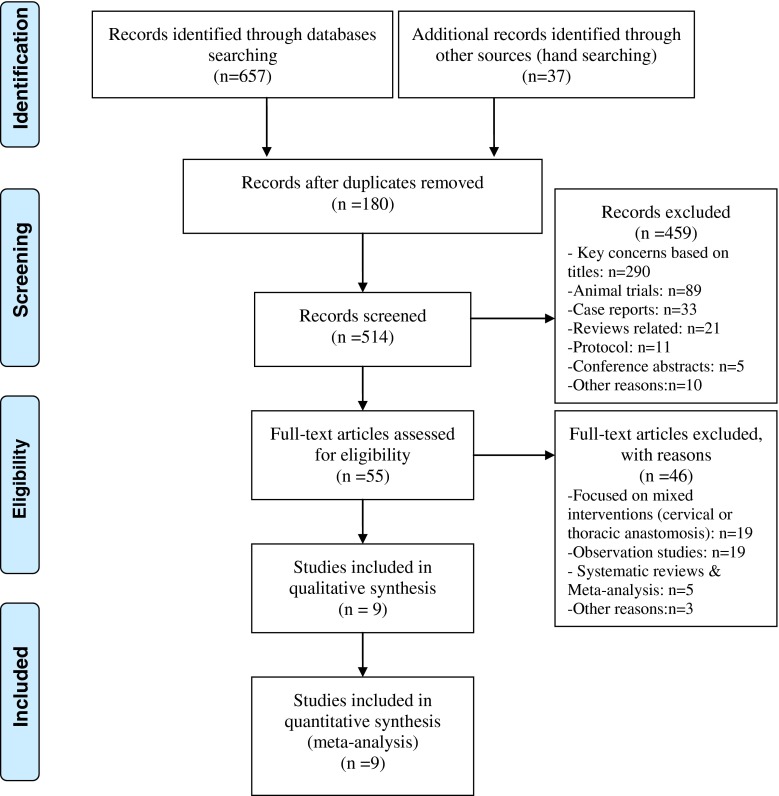

Our initial search strategies yielded 694 potential articles, and there were 514 records after duplicates. Of which, 55 records were selected through reading their titles and abstracts. After checking the full text in detail, nine RCTs [16, 17, 25, 31–36] were identified ultimately which involved 870 patients. Figure 1 shows PRISMA statement of search flows in detail.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram

Baseline Characteristics and Risk of Bias of Included Studies

Of these nine RCTs [16, 17, 25, 31–36], six papers [16, 17, 25, 32–34] were conducted in English, one [31] in French, and two in Chinese [35, 36]. The baseline characteristics of these nine studies are presented in Table 1. Table 2 demonstrated the risk of bias of included studies.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies

| Included studies | Years of studies | Country/District | Design | Cases | Median age (years) | Gender (male/female) | Configuration | Adjuvant therapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS | CS | HS | CS | HS | CS | HS | CS | |||||

| WSHASG 1991 | Apr 1985–Apr 1989 | UK | RCT | 25 | 27 | 63.7 | 65.3 | – | – | NS | NS | NS |

| Law et al. [17] | Nov 1989–Jun 1995 | Hong Kong | RCT | 61 | 61 | 64 | 64 | 54/7 | 53/8 | End to side | End to side | Postoperative radiation |

| Laterza et al. [25] | Feb 1993–Dec 1996 | Italy | RCT | 21 | 20 | 50.9 | 51.9 | 4/17 | 3/17 | End to end | End to side | Preoperative chemoradiation |

| Hsu et al. [33] | Jul 1996–Jul 1999 | Tai Wan | RCT | 32 | 31 | 63 | 61 | 27/5 | 30/1 | End to side | End to side | Preoperative chemoradiation |

| Luechakiettisak and Kasetsunthorn [16] | Oct 2000–Sep 2005 | Thailand | RCT | 59 | 58 | 63.6 | 62.0 | 50/9 | 48/10 | NS | NS | NS |

| Aquino et al. [31] | Jan 2002–Dec 2007 | France | RCT | 15 | 15 | 45.6 | 45.6 | – | – | End to side | End to side | NS |

| Saluja et al. [35] | Jun 2004–May 2010 | India | RCT | 87 | 87 | 50.9 | 51.4 | 54/33 | 61/26 | End to side | Side to side | Preoperative chemoradiation |

| Cai et al. [36] | Sep 2004–Jun 2008 | China | RCT | 125 | 102 | 56 | 59 | – | – | Side to side | Side to side | NS |

| Yang et al. [36] | Jan 2008–Jun 2010 | China | RCT | 22 | 22 | 65 | 67 | 18/4 | 17/5 | Side to side | Side to side | NS |

Table 2.

The risk of bias of included studies

| Included studies | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Incomplete outcome data addressed | Free of selective outcome reporting | Free of other bias | Quality degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WSHASG 1991 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | B |

| Law et al. [17] | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | A |

| Laterza et al. [25] | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | B |

| Hsu et al. [33] | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | B |

| Luechakiettisak and Kasetsunthorn [16] | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | B |

| Aquino et al. [31] | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | B |

| Saluja et al. [35] | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | A |

| Cai et al. [36] | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | C |

| Yang et al. [36] | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | C |

The Results of Meta-analysis

Outcomes on the Effectiveness

Anastomotic Leakages

Nine trials [16, 17, 25, 31–36] reported on anastomotic leakages (phet = 0.10, I2 = 40 %); the fixed model was used, and the available data showed that there was no difference in the incidence of anastomotic leakages (RR = 1.30, 95 % CI 0.87–1.92, p = 0.20). It meant that both HS and CS were equivalent in preventing the leakages. According to the GRADE system, the quality of evidence on anastomotic leakages was moderate (Table 3).

Table 3.

The summary on results of meta-analysis and GRADE system

| Outcome | No. of studies | HS | CS | Effect estimate | Quality of evidence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Total | Events | Total | RR/MD [95 % CI] | p value | |||

| Anastomotic leakage | 9 | 52 | 447 | 38 | 423 | 1.30 [0.87, 1.92] | 0.20 | ⊕⊕⊕⊖Moderatea |

| Anastomotic strictures | 8 | 45 | 330 | 55 | 300 | 0.97 [0.47, 1.99] | 0.93 | ⊕⊕⊕⊖Moderatea |

| Postoperative mortality | 6 | 15 | 275 | 18 | 272 | 0.83 [0.43, 1.58] | 0.57 | ⊕⊕⊕⊖Moderatea |

| Blood loss (ml) | 3 | – | 207 | – | 206 | 39.68 [−6.97, 86.33] | 0.10 | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Lowa,b |

| Operative time (min) | 4 | – | 239 | – | 237 | 18.05 [−3.22, 39.33] | 0.10 | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Lowa,b |

aBecause of the nature of the surgery trials, it was difficult to perform blinding except blinding of the statistician; allocation concealment was unclear in 44.4 % of included studies

bSmall sample size and number of events provided. Additionally, the 95 % CI around the pooled effect was wide

Outcomes on the Security

Anastomotic Stricture

Eight trials [16, 17, 25, 31, 33–36] reported on anastomotic stricture (phet = 0.008, I2 = 63 %); the random model was conducted. It had no benefit in the incidence of anastomotic stricture between the two groups (RR = 0.97, 95 % CI 0.47–1.99, p = 0.93). The quality of evidence on anastomotic stricture was moderate (Table 3).

Postoperative Mortality

Six trials [16, 17, 25, 31, 33, 34] reported on postoperative mortality (phet = 0.65, I2 = 0 %); the fixed model was used, and the result showed that no difference was found in the rate of postoperative mortality (RR = 0.83, 95 % CI 0.43–1.58, p = 0.57). The GRADE system showed that the quality on postoperative mortality was moderate.

Outcomes on the Practicality

Blood Loss

Three trials [16, 17, 34] reported on blood loss (phet = 0.54, I2 = 0 %); the fixed model was chosen. There was no significant difference in blood loss (MD = 39.68; 95 % CI −6.97, 86.33; p = 0.10). The quality on blood loss was low, basing on the GRADE system.

Operative Time

Four trials [16, 17, 33, 34] reported on operative time (phet = 0.0002, I2 = 85 %); the random model was chosen. No difference was found between HS and CS methods (MD = 18.05; 95 % CI −3.22, 39.33; p = 0.10). From the GRADE, we considered that the quality on operative time was low.

Time of Anastomosis

Of the included studies, three trials [33–35] reported on total time of anastomosis. Due to the high risk of heterogeneity (phet < 0.00001, I2 = 100 %), descriptive techniques were used. Cai [35] reported that there was a significant difference between HS and CS (60 ± 12 vs 25 ± 5, p < 0.05); Laterza et al. [25] also drew the conclusion that compared with HS, using CS method could decrease the time of anastomosis (37 ± 12 vs 25 ± 8.2, p < 0.05); however, Saluja et al. [34] demonstrated negative result (27 ± 5.5 vs 25 ± 6.5, p > 0.05).

Hospital Stay

Four trials [32–35] reported on hospital stay. Also, because of the considerable heterogeneity (p < 0.00001, I2 = 96 %), the descriptive techniques were conducted. Only one study [35] concluded that there was no difference in hospital stay, and it meant that the patients with HS had longer hospital stay than those with CS (23 ± 11 vs 12 ± 8, p < 0.05). However, the discordant results were found in the other three trials (p > 0.05) [32–34].

Outcome on the Applicability

Costs

Only two studies [17, 34] reported on suture costs. One study [17] concluded that the HS technique was less costly compared with CS (HS, $3.80; CS, $192.00). And the other study [34] also suggested that HS anastomosis is considerably cheaper (HS, INR220; CS, INR17000).

Discussion

Summary of the Current Researches

As the basic component of esophageal resection, anastomosis is still the key procedure to prevent the postoperative complications. Both HS and CS methods are fashioned in conducting the esophagogastric anastomosis in the past two decades [37]. Several retrospective studies [6, 22, 38], as well as firm evidence from relevant RCTs, have showed that both of them were safe. Meanwhile, with higher costs [17, 34] and being less time-consuming [25, 35], the CS method was associated with higher stricture rate related to high mortality. However, the recent conclusions from certain clinical trials are controversial. The aim of this study is to objectively evaluate the effectiveness, security, practicality, and applicability between the HS and CS methods.

Summary of Included Studies

Nine RCTs [16, 17, 25, 31–36] with 870 patients were identified ultimately, which were published from the year 1991 to 2012 and were conducted in Asia (Hong Kong, Thailand, Tai Wan, Japan, China, and India) and Europe (UK and France). All of them focused on the comparison between HS and CS methods with anastomosis in the neck. When it comes to the surgeons' management, all of included studies had been performed in single center, and four included studies [17, 25, 33, 34] reported clearly the adjuvant therapy, such as pre-/postoperative radiation and chemotherapy. The criteria of all the outcomes were similar in included studies.

All of the included studies had random allocation sequences, and the clear descriptions on the methods of randomization were only seen in one study [25], which had adequate allocation concealment with blind envelops. Because of the inherent methodological property of the surgery trials, it was difficult to perform blinding except blinding of the statistician. Other items were all unclear in included studies (Table 2).

Summary of the Results from the Present Meta-analysis

This study revealed the following important findings: first, there was no significant difference in the risk of developing anastomotic leakages between HS and CS methods with cervical anastomosis, as well as the anastomosis stricture, postoperative mortality, blood loss, and operative time. All of the results could arouse that both the HS and CS methods with cervical anastomosis had equal effects. However, the weak evidence from the descriptive techniques illustrated that the CS method with cervical anastomosis might be less time-consuming, have shorter hospital stay, and higher costs. The quality on outcomes of meta-analysis was moderate to low, the downgrade reason being that it was difficult to perform blinding except blinding of the statistician, and also small sample size and small number of events were provided in the included studies. Meanwhile, the 95 % CI around the pooled effects was wide.

Summary of the Interpretations

Obviously, the cause of an esophageal anastomotic leakage is multifactorial [17]. Apart from local tissue and systemic factors, the inherent properties of the esophagus were supposed to contribute to the risk of leakage, which included the properties of no serosa and also with poor sutures due to lack of longitudinal muscles. So, surgical techniques (HS and CS methods) need to be identified to play an important role in decreasing the postoperative complications.

The CS method was advocated as the preferred method which was perhaps more uniform and less operator-dependent [17]. But our study showed that the HS method was also safe on leakages. Although more stricture formation was confirmed apparently in the current RCTs, our findings illustrated the similar rate of the stricture formation between the two methods with cervical anastomosis. Furthermore, the previous systematic reviews [24] concluded that the CS method was more likely to be associated with postoperative mortality. And our finding also implied that there had been a trend on postoperative mortality in the CS method group (HS, 5.5 %; CS, 6.6 %), but no significant difference was found.

The reasons why stricture formation was frequently seen in the CS group remain worthy of discussion. Firstly, the accurate mucosa-to-mucosa apposition might play a key role because the lack of it would result in excessive fibrosis and stricture formation due to tissue necrosis beyond the stapler line, inflammation, and delayed epithelialization. Secondly, the tension of anastomosis also plays an important role in stricture formation. In order to eliminate tension of anastomosis, a continuous single-layer suture offers coaptation with less risk of tissue strangulation than the CS method or a two-layered HS technique [17]. Thirdly, the esophageal size might be an important factor [16]. And among the included studies, the size of <30 mm was regarded as having an association with incidence of anastomotic stricture in each anastomotic technique [16, 17]. And the subgroup analysis (size ≤25 mm CS vs HS methods) in the previous study [24] also confirms this important factor. Fourthly, anastomotic configuration (end to end, end to side, and side to side) might be also an important factor. And the difference on anastomotic stricture between end to side and end to end was illustrated in the latest RCT [13] and clinical series [39], and these concluded that end-to-side anastomosis is associated with a lower anastomotic stricture rate compared to end-to-end anastomosis.

Meanwhile, the surgical skill varied from different individuals. And all results of this study might be the influence of a learning curve for the operators [40]. Even the learning curve for the creation of the HS method anastomosis was not clearly defined among the included studies.

Summary of Limitations

As for the limitation, the results of the present study should be interpreted with a level of caution because, probably, the number of RCTs included to support firm conclusions was too small. And also the subgroup analyses focusing on the suture material and layers were ignored due to the small number of RCTs included, because it might exaggerate the effects and draw false conclusion if subgroup analysis were done frequently. Furthermore, surgical experience and volumes would impact the outcomes. Other limitations were that although we developed a detailed search strategy, there is still further research that can be undertaken.

Conclusion

Based upon this meta-analysis, the current evidence showed that both HS and CS methods with cervical anastomosis were alternative. And the weak evidence proved that less time of anastomosis was spent in the CS method group, and the cheaper costs were seen in the HS method group. In short, CS could be used as an alternative method for esophagogastric anastomosis in the neck because it is easier and less operator-dependent to apply, but it should not always be regarded as the first choice.

Acknowledgments

We thank the suggestions from Wen Yao (The First Clinical Medical College of Fujian Medical University) for the English language of the manuscript. This review was not supported by a grant from any resources, nor influenced on the design or conduct of the review; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the draft, revision, or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Wang Q and He XR have equal contribution to this study.

References

- 1.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2137–2150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Z-S, Sun Z-X, Zou D-W, et al. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper-GI tract: experience with 1088 cases in China. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J, Wang Q, Ping Y, Zhang Y. Complications after esophagectomy for cancer: 53-year experience with 20,796 patients. World J Surg. 2008;32:395–400. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9349-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacRae HM, McLeod RS. Handsewn vs. stapled anastomoses in colon and rectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:180–189. doi: 10.1007/BF02238246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim T, Yu W, Chung H. Handsewn versus stapled gastroduodenostomy in patients with gastric cancer: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. World J Surg. 2011;35:1026–1029. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urschel J, Blewett C, Bennett W, et al. Handsewn or stapled esophagogastric anastomoses after esophagectomy for cancer: meta–analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dis Esophagus. 2002;14:212–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2001.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis I. The surgical treatment of carcinoma of the oesophagus with special reference to a new operation for growths of the middle third. Br J Surg. 1946;34:18–31. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18003413304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravitch MM, Steichen FM (1979) A stapling instrument for end-to-end inverting anastomoses in the gastrointestinal tract. Ann Surg 189:791–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Ando N, Ozawa S, Kitagawa Y et al (2000) Improvement in the results of surgical treatment of advanced squamous esophageal carcinoma during 15 consecutive years. Ann Surg 232:225–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Hagen JA, DeMeester SR, Peters JH et al (2001) Curative resection for esophageal adenocarcinoma: analysis of 100 en bloc esophagectomies. Ann Surg 234:520–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Whooley BP, Law S, Murthy SC et al (2001) Analysis of reduced death and complication rates after esophageal resection. Ann Surg 233:338–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Valverde A, Hay J-M, Fingerhut A, Elhadad A. Manual versus mechanical esophagogastric anastomosis after resection for carcinoma: a controlled trial. Surgery. 1996;120:476–483. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(96)80066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nederlof N, Tilanus HW, Tran TK, et al. End-to-end versus end-to-side esophagogastrostomy after esophageal cancer resection: a prospective randomized study. Ann Surg. 2011;254:226–233. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822676a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribet M, Debrueres B, Lecomte-Houcke M. Resection for advanced cancer of the thoracic esophagus: cervical or thoracic anastomosis? Late results of a prospective randomized study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;103:784–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walther B, Johansson J, Johnsson F et al (2003) Cervical or thoracic anastomosis after esophageal resection and gastric tube reconstruction: a prospective randomized trial comparing sutured neck anastomosis with stapled intrathoracic anastomosis. Ann Surg 238:803–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Luechakiettisak P, Kasetsunthorn S. Comparison of hand-sewn and stapled in esophagogastric anastomosis after esophageal cancer resection: a prospective randomized study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91(5):681–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Law S, Fok M, Chu K-M, Wong J (1997) Comparison of hand-sewn and stapled esophagogastric anastomosis after esophageal resection for cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 226:169–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Zhang Y, Gao B, Wang H, et al. Comparison of anastomotic leakage and stricture formation following layered and stapler oesophagogastric anastomosis for cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:227–233. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rizk NP, Bach PB, Schrag D, et al. The impact of complications on outcomes after resection for esophageal and gastroesophageal junction carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urschel JD, Sellke FW (2003) Complications of salvage esophagectomy. Med Sci Monitor: Int Med J Exp Clin Res 9:RA173–180 [PubMed]

- 21.Orringer MB, Marshall B, Iannettoni MD. Eliminating the cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leak with a side-to-side stapled anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:277–288. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(00)70183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beitler AL, Urschel JD. Comparison of stapled and hand-sewn esophagogastric anastomoses. Am J Surg. 1998;175:337–340. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim RH, Takabe K. Methods of esophagogastric anastomoses following esophagectomy for cancer: a systematic review. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:527–533. doi: 10.1002/jso.21510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honda M, Kuriyama A, Noma H, et al. Hand-sewn versus mechanical esophagogastric anastomosis after esophagectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2012;257(2):238–248. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826d4723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laterza E, Manzoni G, Veraldi GF, et al. Manual compared with mechanical cervical oesophagogastric anastomosis: a randomised trial. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:1051–1054. doi: 10.1080/110241599750007883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines report from an American College of Chest Physicians Task Force. Chest J. 2006;129:174–181. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al (2008) Rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations: what is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ: Br Med J 336:995–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langer G, Meerpohl J, Perleth M et al (2012) GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen 106:357–368 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Aquino JLB, Camargo JGT, Said MM, et al. Cervical esophagogastric anastomosis evaluation with a mechanical device versus manual suture in patients with advanced megaesophagus. Revista do Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões. 2009;36:19–23. doi: 10.1590/S0100-69912009000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George W. Suturing or stapling in gastrointestinal surgery: a prospective randomized study. Br J Surg. 1991;78:337–341. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu H-H, Chen J-S, Huang P-M, et al. Comparison of manual and mechanical cervical esophagogastric anastomosis after esophageal resection for squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2004;25:1097–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saluja SS, Ray S, Pal S, et al. Randomized trial comparing side-to-side stapled and hand-sewn esophagogastric anastomosis in neck. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1287–1295. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai RJ, Li M, Xiong G et al (2012) Comparative analysis of mechanical and manual cervical esophagogastric anastomosis following esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. J South Med Univ 32(6):908–909 [PubMed]

- 36.Yang L, Zheng YF, Jiang JQ et al (2012) Comparison of esophagogastric side-side anastomosis and hand-sewn end-side anastomosis in neck after esopphagectomy for caricinoma. Chongqing Medicine 41:3155–3156

- 37.Vigneswaran WT, Trastek VF, Pairolero PC, et al. Transhiatal esophagectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:838–846. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)90341-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong J, Cheung H, Lui R et al (1987) Esophagogastric anastomosis performed with a stapler: the occurrence of leakage and stricture. Surgery 101:408–415 [PubMed]

- 39.Haverkamp L, van der Sluis PC, Verhage RJ, et al. End-to-end cervical esophagogastric anastomoses are associated with a higher number of strictures compared with end-to-side anastomoses. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(5):872–876. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haverkamp L, van der Sluis PC, Ruurda JP-H, van Hillegersberg R. End-to-end versus end-to-side esophagogastrostomy after esophageal cancer resection: a prospective randomized study. Ann Surg. 2012;254(2):226–233. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827b9d07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]