Abstract

Diagnosis of abdominal wall hernia is often a clinical problem, especially in occult or in obese patients. Multidetector CT is an accurate method of detecting various types of abdominal and diaphragmatic hernias. It clearly demonstrates the anatomical sites of hernial sac, its contents and possible complications.

Keywords: CT, Imaging, Abdominal, Diaphragmatic, Hernias

Introduction

Hernia occurs when the contents of a body cavity bulge out of the area where they are normally contained. Abdominal wall hernias are usually diagnosed on the basis of clinical examination and sometimes conventional diagnostic imaging technique like x-ray films, barium studies and herniography. Physical examination alone can be difficult and unrewarding in obese patients, and in patients with previous surgery of the abdominal wall. Especially in these patients when clinical diagnosis is difficult, computed tomography enables easier recognition of the type of hernia, contents of the hernial sac and any complications. CT also allows differential diagnosis from other abdominal wall swellings such as neoplasia, hematomas, abscesses and undescended testicle [1–3]. With recent advances in computed tomography (CT) scan techniques, it is possible to generate three-dimensionally (3D) reconstructed images for better depiction [4].

We retrospectively reviewed all cases of abdominal wall hernias and diaphragmatic hernias, done at our institution over a four-year period. All the CT scans were done using a multidetector CT scan (4 slice and 16 slice spiral CT scan), using a standard abdominal protocol (with oral and intravenous contrast). Thinner reconstructions at 2.5/ 3.75 mm interval were done wherever indicated. Mutiplanar reformations were also done in individual cases depending upon the need to do so.

This pictorial essay depicts the CT findings of abdominal wall hernias and diaphragmatic hernias.

Types of Abdominal Wall Hernia

Abdominal wall hernias are classified as external when the hernia sac is clinically palpable and occult external when the condition, congenital or acquired (through trauma or postoperatively), is due to the involvement of ansae within the abdominal wall that do not appear on the surface [5, 6]. The different types of abdominal wall hernias include (a) inguinal hernia, (b) femoral hernia, (c) umbilical hernia, (d) incisional hernia, (e) spigelian hernia, (f) epigastric hernia and (g) lumbar hernia.

Inguinal Hernia

Inguinal hernias are the most common abdominal wall hernias in adults . They are more common in men than women. They are of two types: indirect inguinal hernia and direct inguinal hernia. An indirect hernia may occur at any age but become more common as people age. The hernia enters the inguinal canal via a patent processus vaginalis through the deep inguinal ring and is localized lateral to the inferior epigastric artery at its origin. Computed tomography is useful in depicting the extent and content of the hernial sac (Fig. 1) [7, 8].

Fig. 1.

Indirect inguinal hernia. CT scan shows a hernial sac (arrow) with bowel loops in the right inguinal region extending into the scrotum

Direct inguinal hernia almost always occurs in the middle aged and elderly because their abdominal wall weakens as they age. Direct inguinal hernias (Fig. 2) are located medial to the inferior epigastric artery and are due to the defects in the fascia transversalis and conjoint tendon which forms the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. It rarely extends into the scrotum.

Fig. 2.

Direct inguinal hernia. CT scan shows bilateral hernial sacs in the inguinal region. The hernial sac is located medial to the epigastric vessels (arrow)

Femoral Hernia

Femoral hernias are more common in women than men, although inguinal hernias are still more common than femoral hernias in women [9]. The femoral canal is the path the femoral artery, vein and nerve leave the abdominal cavity to enter the thigh. Although normally a tight space, sometimes it becomes large enough to allow the abdominal contents into the canal. Hernia is located between the external femoral vein and the gimbernats lacunar ligament medially (Fig. 3).

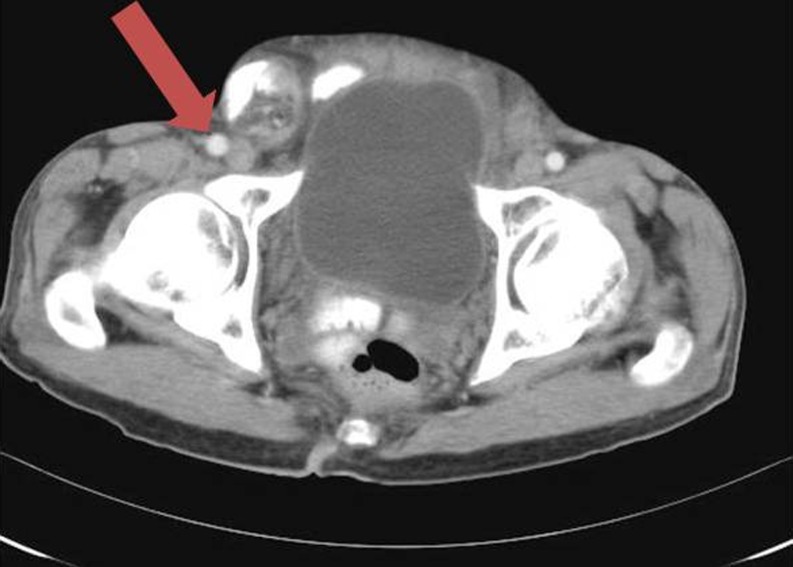

Fig. 3.

Femoral hernia. CT scan shows contrast filled bowel loops passing through the right femoral canal, medial to the femoral vessels (arrow)

Umbilical Hernia

Umbilical hernias are common in infancy and are noted at birth as a protrusion at the umbilicus. They develop when the umbilical ring fails to close spontaneously after the umbilical cord separates. If small, the hernia closes gradually by the age of two. The risk of incarceration and strangulation increase with age and surgical repair is recommended for umbilical hernias that persist for more than 4 years [10]. Even if the area is closed at birth, umbilical hernias can appear later in life because this spot remains a weaker place in the abdominal wall (Fig. 4). Multiple pregnancies, obesity and ascites are risk factors [11]. CT is more helpful in diagnosing atypical cases, when umbilical hernia can be distinguished from less common lesions such as urachal cysts [12]. Although ultrasound can also delineate contents [13], CT scan is obviously the superior diagnostic modality in these patients.

Fig. 4.

Umbilical hernia. CT scan shows a large hernial sac containing multiple bowel loops and fat

Incisional Hernia

Incisional hernias occur in the area of any prior incision. Approximately, 10% of all anterior abdominal wall closures are complicated by incisional hernias [14]. Elderly and obese patients are more prone for incisional hernias. The other local risk factors include postoperative infections, long vertical incisions and abdominal distension. CT enables distinguishing wound hematoma from early wound dehiscence in acute postoperative phase when clinical examination is difficult (Fig. 5) [15, 16].

Fig. 5.

Incisional hernia in a 56-year-old female with herniated bowel loops (bold arrow) at the level of operative scar (thin arrow)

Spigelian Hernia

Spigelian hernia is a rare acquired interparietal hernia, accounting for less than 2% of all anterior abdominal wall hernias [17–19]. They are usually seen in women above the age of 50 years and who are often overweight. It is due to defect of the aponeurosis between the transverses abdominis and the rectus muscle (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Spigelian hernia. CT scan shows herniation of opacified bowel loops (arrow) and mesenteric fat through a defect of aponeurosis between right rectus abdominus and aponeurosis of right transverse abdominus. Lateral margin of hernial sac is the intact external oblique muscle and fascia

They are seen external to the rectus muscle and inferior to the external oblique muscle in the area between the umbilical scar and the anterosuperior iliac spine along the semilunar line. Computed tomography confirms the diagnosis when the external oblique aponeurosis is defective and the subcutaneous hernial sac may be confused with a lipoma of the abdominal wall [11, 19].

Epigastric Hernia

Epigastric hernia develop in the mid-upper abdomen along the xipho-umbilical line through stretching of linea alba . The hernia sac usually contains omentum and not uncommonly small bowel, transverse colon and rarely stomach [20] and liver [21]. Computed tomography performed with valsalva maneuver helps in identifying the hernia [22].

Lumbar Hernia

Lumbar hernias are uncommon hernias [23]. They can be congenital [24] or can occur after surgery [23], blunt trauma, or fracture or partial surgical resection of the illium [25]. They occur in the posterior flank through defects of the lumbar muscles and aponeurosis, located below the 12th rib, above iliac crest, posterior to the erector spinae muscle in the superior (Grynfeltt-Lesgaff) lumbar triangle or inferior (petits) lumbar triangle (Fig. 7). CT easily demonstrates lumbar hernia in obese patients and postoperative patients [26].

Fig. 7.

Lumbar hernias. CT scan shows mesenteric fat and collapsed large bowel loop in the left posterolateral part of the abdominal wall, through lumbar triangle (arrow)

Diaphragmatic Hernias

The incidence of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is 1 per 3000 live births [27].

The diaphragm is a musculotendinous structure that separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity. It is derived from four embryonic structures: septum transversum, pleuroperitoneal membranes, mesoderm of the body wall and esophageal mesenchyme. The pleuroperitoneal canals are closed at 6–7 weeks of gestation. The commonest defect is the posterolateral diaphragmatic defect (Bochdalek hernia), which is postulated to result from failure of closure of the pleuroperitoneal canal. Other diaphragmatic defects include anterior defect (Morgagni) or central. The central defect (defect of central tendon and septum transversum) leads to the peritoneopericardial hernia. Other types of diaphragmatic hernias include hiatus hernia, and traumatic diaphragmatic hernia.

Bochdalek Hernia

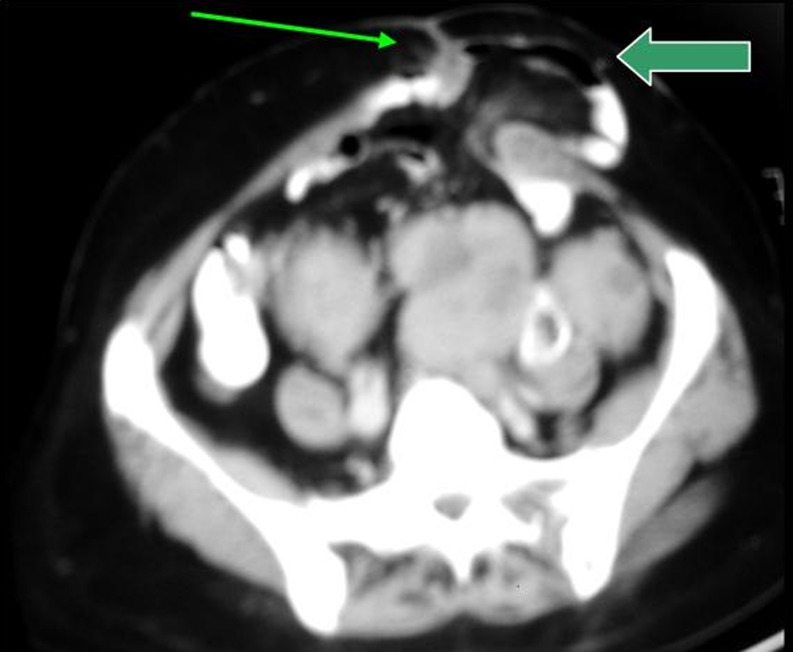

The more common type of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (80–85%), Bochdalek hernia, occurs through posterolateral diaphragmatic defects. Approximately, 85–90% of these occur on the left side. CT shows discontinuity of the diaphragm, with herniation of both small and large bowels as well as intrabdominal solid organs into the thoracic cavity (Fig. 8). In adults, the defect is likely to be acquired.

Fig. 8.

Bochdalek hernia: CT scan shows discontinuity in right posterolateral part of diaphragm (arrow)

Morgagni’s Hernia

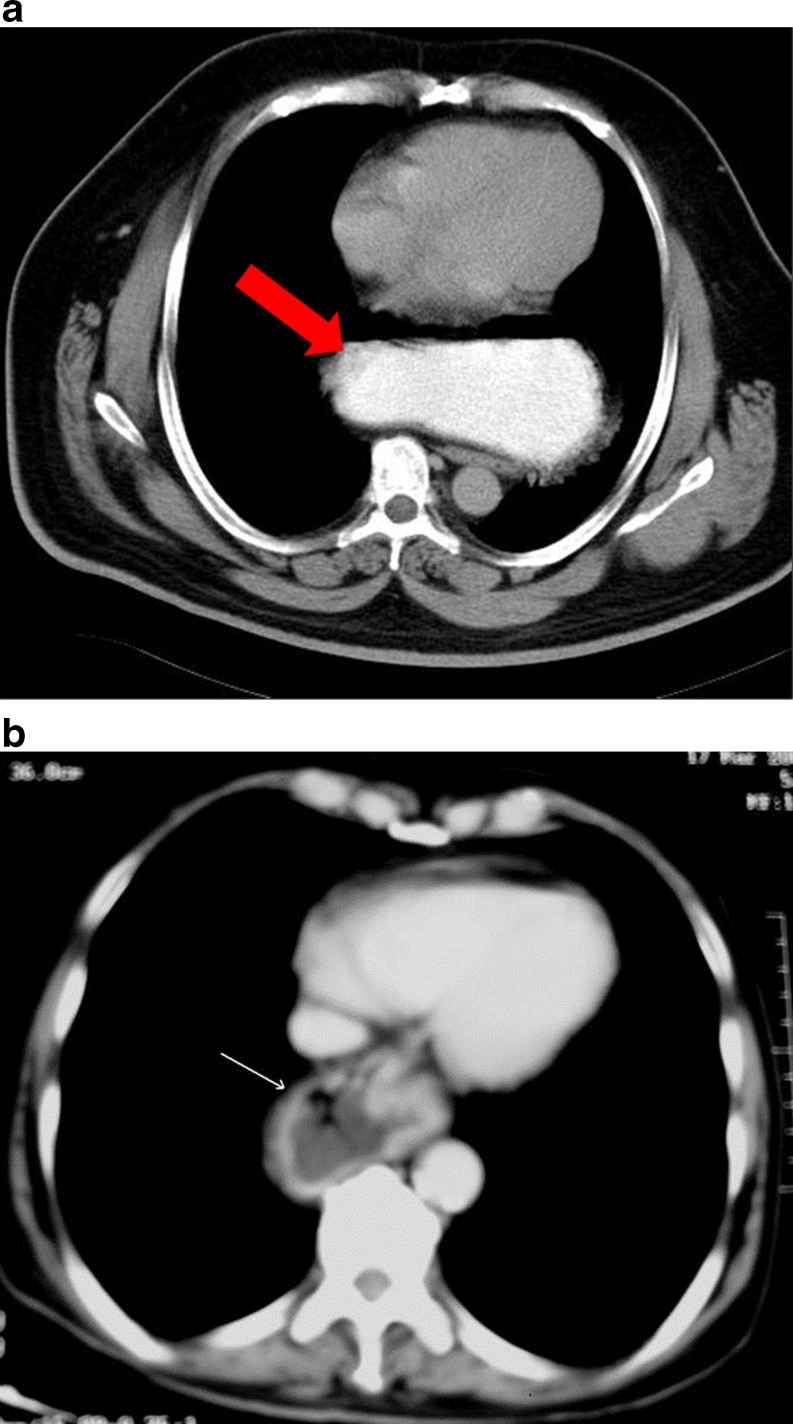

This is a rare form of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. It occurs through a potential defect in the right anterior medial part of the diaphragm posterior to the sternum. The defect is due to failure of fusion of the sternal and costal fibers of diaphragm. Liver, mesenteric fat and bowel can herniate through the defect (Fig. 9a-b) [28].

Fig. 9.

Morgagni hernia: Axial (a) and coronal (b) CT scan shows herniation of bowel loops with mesentery into the right hemithorax. Neck of the sac lies in the anterior paramedian location

Hiatal Hernia

Hiatal hernia is of two types: commoner sliding hiatal hernia and less common paraesophageal hernia. The gastroesophageal junction is above the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm in sliding hernia, whereas the gastroesophageal junction is below the diaphragm in paraesophageal hernia. There is herniation of part or whole of the stomach into the chest through a weakened/torn phrenoesophageal membrane in these hernias. Although these are best demonstrated on esophagogram, they can also be detected easily on a CT scan (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Hiatus hernia (a) CT scan shows contrast filled stomach (arrow) in the chest (b) CT scan shows air and fluid filled fundus of stomach in chest

Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia

Diaphragmatic rupture can result following major blunt trauma to the lower thorax or abdomen in up to 6% of patients [29, 30]. It is more common on the left side due to an area of congenital posterolateral weakness on the left side and protective effect of the liver on the right hemidiaphragm [31–34]. Helical CT with thinner axial images and higher quality of reformatted images has proven to be more valuable in preoperative detection of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Traumatic diaphragmatic Hernia (a–b) CT scan shows discontinuity in right posterolateral part of diaphragm along with free fluid and herniation of colon into the right chest

CT signs of diaphragmatic injury include direct visualization of injury (free edge of the disrupted diaphragm demarcating the defect is seen), segmental diaphragm non-visualization (low specificity), intrathoracic herniation of viscera, collar sign (focal constriction of the herniated bowel or omentum ) which shows a high specificity of 80.7–100% [31, 32], dependent viscera sign (viscera lies dependent against the posterior chest wall) which shows a specificity of 71–96.5% [32], diaphragm thickening, intramuscular hematoma and peridiaphragmatic active contrast extravasation.

The most commonly herniated viscera is the stomach and colon on the left side and the liver on the right side.

References

- 1.Wechsler RJ, Kurtz AB, Needleman L, Dick BW, Feld RI, Hilpert PL, Blum L. Cross sectional imaging of abdominal wall hernias. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:517–521. doi: 10.2214/ajr.153.3.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee G-HM, Cohen AJ. CT imaging of abdominal hernias. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:1209–1213. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.6.8249727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sodhi KS, Narsimhan KL, Bhattacharya A, Khandelwal N. Bilateral congenital diaphragmatic eventration: an unusual cause of respiratory distress in an infant. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2011;8:259–260. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.86082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sodhi KS, Aiyappan SK, Saxena AK, Singh M, Rao K, Khandelwal N. Utility of multidetector CT and virtual bronchoscopy in tracheobronchial obstruction in children. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:1011–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fish AE, Brodey PA. Computed tomography of the anterior abdominal wall: normal anatomy and pathology. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1981;5:728–733. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198110000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguirre DA, Santosa AC, Casola G, Sirlin CB. Abdominal wall hernias: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at multi-detector row CT. Radiographics. 2005;25:1501–1520. doi: 10.1148/rg.256055018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fataar S. CT of inguinal canal lipomas and fat-containing inguinal hernias. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2011;55:485–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2011.02288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkhardt JH, Arshanskiy Y, Munson JL, Scholz FJ. Diagnosis of inguinal region hernias with axial CT: the lateral crescent sign and other key findings. Radiographics. 2011;31:E1–E12. doi: 10.1148/rg.312105129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ponka JL. Anatomy. In: Ponka JL, editor. Hernias of the abdominal wall. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1980. pp. 18–39. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowe ML, O’Neill JA, Grosfeld JL, et al. Disorders of the umbilicus. In: Rowe M, Oneill JA, Grosfeld JL, et al., editors. Essentials of pediatric surgery. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995. pp. 1029–1043. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller PA, Mezwa DG, Feczko PJ, Jafri ZH, Madrazo BL. Imaging of abdominal hernias. Radiographics. 1995;15:333–347. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.15.2.7761639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khati NJ, Enquist EG, Javitt MC. Imaging of the umbilicus and periumbilical region. Radiographics. 1998;18:413–431. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.18.2.9536487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saggar K, Goyal SC, Goyal R, Sodhi KS. Ultrasonographic detection of herniation of stomach in paraumbilical hernia. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1999;18:87–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bucknall TE, Cox PJ, Ellis H. Burst abdomen and incisional hernia: a prospective study of 1129 major laparotomies. Br Med J. 1982;284:931–933. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6320.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhangu A, Fletcher L, Kingdon S, Smith E, Nepogodiev D, Janjua U. A clinical and radiological assessment of incisional hernias following closure of temporary stomas. Surgeon. 2012 Jan 25. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Somers JM, Pollard SG, Dixon AK. The recognition of previous abdominal surgery by computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991;15:95–100. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199101000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiller N, Alberton Y, Shapira Y, Hadas-Halpern I. Richters hernia strangulated in a spigelian hernia: ultrasonic diagnosis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1994;22:503–505. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870220808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganz E, Tazzioli G, Mosca D, Amorotti C, Speranza M. Ventrolateral hernias of the abdominal wall. The anatomicopathologic, clinical and therapeutic consideration. Minerv Chir. 1997;52:1441–1445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gough VM, Vella M. Timely computed tomography scan diagnoses spigelian hernia: a case study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:W9–W10. doi: 10.1308/147870809X450629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serou F, Amsterdam E, Levis S, Krispin M. Gastric involvement in an epigastric hernia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:893–894. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.4.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta AS, Bothra VC, Gupta RK. Strangulation of liver in epigastric hernia. Am J Surg. 1968;115:843–844. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(68)90531-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hojer AM, Rygarrd H, Jess P. CT in the diagnosis of abdominal wall hernias: a prelimary study. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:1416–1418. doi: 10.1007/s003300050309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith DC. Umbilical, epigastric and rare abdominal wall hernias. In: Morris PJ, Wood WC, editors. Oxford textbook of surgery. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakhlu A, Wakhlu AK. Congential lumbar hernia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16:146–148. doi: 10.1007/s003830050048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castelein RM, Sauter AJ. Lumbar hernia in an iliac bone graft defect. A case report. Acta orthop Scand. 1985;56:173–174. doi: 10.3109/17453678508993012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker ME, Weinerth JL, Andriani RT, Cohan RH, Dunnick NR. Lumbar hernia: diagnosis by CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:565–567. doi: 10.2214/ajr.148.3.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torfs CP, Curry CJ, Bateson TF, Honoroe LH. A population-based study of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Teratology. 1992;46:555–565. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420460605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altinkaya N, Parlakgümüş A, Koc Z, Ulusan S. Morgagni hernia: diagnosis with multidetector computed tomography and treatment. Hernia. 2010;14:277–281. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0608-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward RE, Flynn YC, Clark WP. Diaphragmatic disruption secondary to blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1981;21:35–38. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voeller GR, Reisser JR, Fabian TC, et al. Blunt diaphragm injuries: a five-year experience. Am Surg. 1990;56:28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Killeen KL, Mirvis SE, Shanmuganathan K. Helical CT of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture secondary to blunt trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:1611–1616. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.6.10584809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sliker CW. Imaging of diaphragm injuries. Radiol Clin North Am. 2006;44:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen HW, Wong YC, Wang LJ, Fu CJ, Fang JF, Lin BC. Computed tomography in left-sided and right-sided blunt diaphragmatic rupture: experience with 43 patients. Clin Radiol. 2010;65:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nwafor IA, Eze JC, Aminu MB. Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture through the central tendon with herniation of the stomach and coils of small bowel into the pericardial cavity. Niger J Med. 2011;20:492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]