Abstract

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast is a potentially invasive neoplasm. Risk factors include high estrogen states such as use of oral contraceptive (OC) pills, nulliparity, advanced age at first birth, and also family history and genetic mutations. The incidence of this usually clinically silent condition has risen in the past few decades due to widespread screening and diagnostic mammography, with final diagnosis confirmed by biopsy. At present, treatment options include total or simple mastectomy or lumpectomy with radiation. Adjuvant therapy includes antiestrogens like tamoxifen and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) suppression therapy. With the latest advances in chemotherapy and better understanding on the pathogenesis of the lesion, it is anticipated that more effective modalities of treatment may soon be available.

Keywords: Ductal carcinoma in situ, Mastectomy, Lumpectomy, NSABP trials

Introduction

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast is the proliferation of malignant epithelial cells within the mammary ductal system without involving the basement membrane. There is no evidence of invasion into the surrounding stroma. This lesion, a precursor to invasive ductal carcinoma, has risen in incidence over the last couple of decades due to the wide use of screening mammography [1]. In the USA, DCIS incidence rose from 1.87 per 100,000 in 1973–1975 to 32.5 in 2004. Incidence increased in all ages but more so in women older than 50 years [2]. DCIS constitutes 20–25 % of all newly diagnosed breast cancer cases [3] and 17–34 % of mammographically detected neoplasms [4, 5]. Advances in molecular biology and pathology have led to a better understanding on the evolution from ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive cancer.

Studies suggest that between 14 and 53 % of DCIS may progress to invasive cancer over a period of ten or more years. The reported prevalence of undiagnosed DCIS in autopsy studies, of approximately 9 %, has been used to suggest that a larger reservoir of DCIS may exist in the population [6].

Pathogenesis

This condition lies along a spectrum of lesions from atypical hyperplasia to invasive ductal carcinoma.

Various factors have been implicated in the development of the condition. Chromosomal imbalances including loss of heterozygosity occur in more than 70 % of high-grade carcinomas [7].

Molecular markers, such as expression of the estrogen receptor, overexpression of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)/neu proto-oncogene and mutation in the p53 tumor suppressor gene have been identified [8, 9]. The expression of these markers is similar to that in invasive cancer. Hence, the factors causing DCIS are those implicated in invasive cancer as well.

Kerlikowske and colleagues [10] conducted standardized pathology reviews and immunohistochemistry staining for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), Ki67 (tumor proliferating index) antigen, p53, p16, epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (ERBB2, HER2 neu oncoprotein), and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in paraffin-embedded DCIS tissue. They found that DCIS lesions positive for p16, COX-2, and Ki67, or those detected by palpation are more likely to develop into invasive cancer.

Radisky and colleagues found that though previous studies claimed that expression of p16 in tissue biopsies of patients with DCIS is associated with increased risk of breast cancer, particularly when considered in combination with other markers such as Ki-67 and COX-2, such an association between expression and breast cancer did not exist [11].

Increased exposure to estrogen, related to use of oral contraceptive (OC) pills, nulliparity, older age at first birth, or use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) after menopause are associated with an increased risk for DCIS [12–14]. Compared to those who never received hormone replacement therapy, women who took hormone replacement therapy for less than 5 years had significantly lower risk of DCIS. While the Iowa Women’s Health Study found that there was no increased risk of DCIS in women who received HRT compared with those who did not [15], a subsequent meta-analysis found that women who had previously taken HRT had a higher risk of developing DCIS [15].

Familial factors include family history of DCIS/invasive cancer. Mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes have been implicated, which significantly increase the risk of developing DCIS/invasive disease [16].

Pathology

The subtypes of DCIS were divided by Allred [17] into the following:

Comedo group, large cell: more aggressive form.

Noncomedo group, small cell: less aggressive form, which is further divided into cribriform, micropapillary, and solid forms.

However, as more cases were diagnosed, pathologists believed that it was not easy to classify types into comedo and non-comedo types, and newer classification systems were proposed. One such system is the Van Nuys pathological classification. It classifies DCIS into low grade (nuclear grade 1 or 2), further divided into two types based on the presence or absence of necrosis and high grade (nuclear grade 3).

| 1.DCIS with no central necrosis (noncomedo group) |

| 2.Low grade with no central necrosis |

| (a) low-grade DCIS |

| (b) intermediate-grade DCIS: well differentiated, cribriform, micropapillary, solid-, and small-cell type |

| 3.DCIS with central necrosis |

| (a) poorly differentiated |

| (b) comedo type |

| (c) large-cell type |

Diagnosis

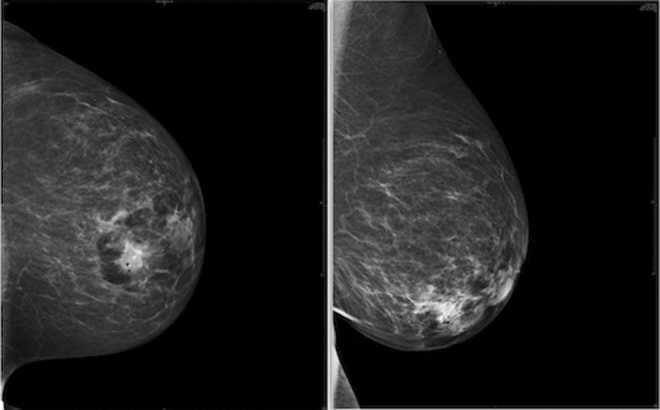

Ductal carcinoma in situ is clinically silent in most cases. Before the widespread use of screening mammography, DCIS used to be diagnosed when patients presented with a lump in the breast or bloody nipple discharge. However, as of today, most lesions are detected on routine screening mammographs (Fig. 1). They are seen most commonly as microcalcifications (in 76 % cases) or sometimes as masses/soft tissue densities (in 11–13 % of cases) [18].

Fig. 1.

Mammographs showing lesions

Once detected on a mammogram, it is usually followed up by a biopsy. Stereotactic core needle biopsy is the procedure of choice, and use of a vacuum-assisted device improves diagnostic accuracy [19]. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) cannot distinguish between invasive and noninvasive cancer, and biopsy is a must. Furthermore, those patients diagnosed with DCIS on stereotactic biopsy should undergo surgical resection to remove the lesion and also rule out invasive cancer, which is present in 10–15 % of cases.

The overall cancer prevalence among women undergoing biopsy was 22.4 %.

Prevalence in women with mammograms highly suggestive of malignancy (category 5) was 84.6 %, with minimal variation in individual cancer probabilities due to age. A total of 24.6 % of women with suspicious mammograms (category 4) had cancer, but individual probability estimates ranged from .01 to .86, depending on age, presence of a lump, previous biopsy, menopausal status, and use of postmenopausal hormone therapy. These variables also influenced biopsy outcome in women with other mammography assessments (categories 0–3), but the overall prevalence was lower (8.6 %), and estimated probabilities ranged from .01 to .45. When cancer was present, the probability of invasive disease was influenced by mammogram assessment category, absence of mammogram calcifications, and presence of a lump [20].

Immunohistochemical analysis for ER and PR status and HER2 expression may be done to guide chemotherapy.

DCIS is accurately detected with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but the typical malignant features are inconsistently seen and most often in high-grade DCIS or in DCIS with a small invasive component. The histopathologic extent of DCIS is more accurately demonstrated with MRI. However, overestimation due to benign proliferative lesions does frequently occur. An improved depiction of DCIS could lead to improved preoperative staging. Conversely, the identification of more extensive disease on MRI could give rise to unnecessary interventions. Therefore, MRI should be used carefully and preferable in specialized and experienced centers. Therefore, to date, there is no evidence that the use of MRI improves outcomes (decreased recurrence rates) in patients with DCIS [21].

Treatment

Management of ductal carcinoma in situ is a team effort, comprising coordinated care provided by oncologists, surgeons, radiologists, and pathologists.

The primary decision that needs to be made is whether the patient is a candidate for breast-conserving surgery. Simple mastectomy is curative for over 98 % of cases [22]. Recurrences may occur in 1–2 % of cases due to unrecognized invasive carcinoma, inadequate margins, or incomplete removal of breast tissue during the surgery. Usually, the procedure is followed by immediate breast reconstruction.

At present, most patients are treated by breast-conserving surgery, commonly referred to as lumpectomy, followed by radiation therapy [23]. However, breast-conserving surgery is indicated in cases in which the lesion is limited to one quadrant, may be continuous or multiple small foci. For nonpalpable lesions, needle localization techniques are used to guide the resection. DCIS to breast ratio is an important factor is treatment decisions. A post-excision mammogram is done, and the surgery is normally followed by radiotherapy to eradicate residual disease.

Surgical margins during excision are an important prognostic factor in determining local recurrence. Though there is no varying data on the exact surgical margin, a 1–2-mm margin is recommended for patients, and the dissection is carried down to and includes the pectoral fascia. According to Holland and Faverly, when the margin width exceeds 10 mm, the risk of residual disease is very small [24].

The adequacy of excision appears to correlate with local control but is imprecisely defined by margin status alone. Based upon recent data, it appears that atypical ductal hyperplasia and cancerization of lobules in the context of coexistent DCIS may need to be considered as part of the DCIS lesion that should be excised. This issue may account for some of the disparate results of different studies on DCIS. For statistical purposes, recent studies also suggest that only recurrences developing within or adjacent to the bed of the initial DCIS lesion should be considered when analyzing factors associated with outcome. Recurrences developing elsewhere in the breast may include new DCIS and invasive lesions that bear no biologic relationship with the initial DCIS lesion. Finally, since it is impossible to insure that all DCIS has been removed, it may be more appropriate to consider DCIS lesions as adequately or inadequately excised instead of completely or incompletely excised. Since DCIS is essentially a microscopic disease, pathologists should have a primary role in helping to define the adequacy of excision [25].

Neither axillary dissection nor sentinel lymph node biopsy is routinely indicated in management, owing to very low rate of axillary node metastasis [26]. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is not possible after mastectomy and, hence, considered in patients undergoing mastectomy because 10–20 % have occult invasive cancer. After surgery, radiotherapy is administered to the whole breast in a dose of 44–50 Gy, given in fractions of 180–200 cGy daily over 5–6 weeks. Radiation therapy reduces the risk of local invasive and noninvasive disease. The NSABP B-17 trial showed that rate of ipsilateral invasive recurrence was significantly lower with adjuvant radiotherapy as compared to excision alone (8.9 vs 19.4 %); however, overall survival was similar [27]. There is some literature that suggests the use of balloon brachytherapy following lumpectomy [28].

Chemotherapy with tamoxifen has shown to reduce recurrence and occurrence of contralateral disease. The NSABP B-24 trial showed 32 % reduction in incidence of ipsilateral invasive breast cancer [27]. There is reduction in the incidence of contralateral breast cancer as well, and the incidence remains low even after discontinuation of tamoxifen. However, the exact benefit is unclear as conflicting results were found in trials. Although tamoxifen treatment prevented both invasive breast cancer and DCIS, raloxifene treatment decreased incidence of invasive breast cancer, but not DCIS [2].

Currently, third-generation aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane) are also used as chemoprevention agents with greater specificity and fewer side effects [29]. However, all of these chemopreventive drugs have no impact on ER tumors, and this remains a challenging area for breast cancer prevention. Possible agents for prevention of ER-negative neoplasms include cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, statins, and vitamin D analogs. Yet none of these drugs has been tested in humans in a randomized controlled trial, which is necessary to prove the efficacy of these drugs for prevention of breast cancer.

There is one laboratory study in progress that is evaluating inhibition of p38 kinase as a chemopreventive measure for ER-negative breast tumors [30]. Whereas p38 has previously been considered as a mediator of stress-induced apoptosis, it proposes that p38 may have dual activities regulating survival and proliferation depending on the expression of p53. Because most ER-negative breast tumors express mutant p53, the results provide the foundation for future development of p38 inhibitors to target p38 for the treatment of p53 mutant and ER-negative breast cancers.

Rexinoid LG100268 has been shown in animal models to be an effective chemopreventive agent for prevention of preinvasive neoplasm of the breast with minimal toxicity. Long-term treatment with a novel Rexinoid, LG100268 significantly prevented invasive mammary tumor development. Short-term treatment of LG100268 significantly prevented the development of preinvasive mammary lesions including hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ [31]. Future trials in humans are needed to assess the clinical translation of this chemopreventive agent.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR)-α and PPAR-γ ligands induce apoptotic and antiproliferative responses, respectively, in human breast cancer cells, and their activation is associated with specific changes in gene expression [32]. Therefore, PPAR-selective retinoids may also be potential chemopreventive agents.

Anti-HER2 therapy such as trastuzumab and lapatinib are being studied.

The role of prophylactic mastectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers has been talked about. In a study conducted at the Mayo Clinic over a span of 13.4 years, results suggest that the risk of breast cancer is reduced by 89.5–100.0 % in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers after prophylactic mastectomy [33].

Usually, patients with DCIS have an excellent prognosis. Overall, the 15-year survival exceeds 85 %, and incidence of death from breast cancer is less than 5 %. Younger age, positive surgical margins, tumor size and grade, and comedo necrosis were consistently related to DCIS recurrence [2].

Nearly all patients who develop a noninvasive recurrence following breast-sparing surgery are cured with mastectomy, and approximately 75 % of those with an invasive recurrence are salvaged. Selected patients initially treated by lumpectomy alone may also undergo breast conservation therapy at the time of relapse according to the same strict guidelines of tumor margin clearance required for the primary lesion; radiation therapy should be given following local excision. The use of systemic therapy in patients with invasive recurrence should be based on standard criteria for invasive breast cancer [34].

The Van Nuys prognostic index (VNPI) is a widely used prognostic tool that uses tumor size, margin width, and nuclear grade of the tumor to predict outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Van Nuys Prognostic Index scoring system

| Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Tumor size (mm) | ≤15 | 16–40 | ≥41 |

| Margin width (mm) | ≥10 | 1–9 | <1 |

| Pathological classification | Nuclear grades 1/2 not high grade, no necrosis |

Nuclear grades 1/2 not high grade, with necrosis |

Nuclear grade 3 high grade, with/without necrosis |

Scores 1–3 for each of the predictors are totaled to yield an index score ranging from a low of 3 to a high of 9. Score 3/4: no difference in survival free of recurrence at 12 years regardless of whether they had had radiotherapy; hence, it can be considered for excision only. Score 5/6/7: significant decrease in local recurrence rates after radiotherapy; hence, it should be treated with excision + radiotherapy. Score 8/9: unacceptably high local recurrence rates; treatment of choice is mastectomy

A novel technique, the Oncotype DX test, can help determine the likelihood of DCIS returning or the tumor returning as invasive breast cancer in the same location, also known as local recurrence. The test works by examining a sample of the tumor tissue that has already been removed during the original surgery. The test measures a group of cancer genes in the tissue sample to study how they are expressed. The result of the test is reported as a number between 0 and 100, known as the DCIS score results, and is plotted in two separate graphs. One graph represents the chances of any tumor coming back in the same breast (either a DCIS or invasive breast cancer). A lower DCIS score result means that there is a lower chance that this will occur, and a higher score means that there is a higher chance that this will occur. The other graph represents the chances of the tumor coming back in the same breast as an invasive breast cancer. A lower score means that there is a lower chance that this will occur, and a higher score means that there is a higher chance that this will occur. The Oncotype DX test for DCIS provides information in addition to traditional measurements (such as margin width, tumor size, and tumor grade) that doctors have traditionally used to estimate how likely a patient’s cancer is to return and to help them make treatment decisions.

Conclusion

Ductal carcinoma in situ is a neoplasm whose nature is still not completely understood. With the advances in imaging, the incidence of DCIS has increased since the past couple of decades. Screening mammography detects the lesions in the early stages as microcalcifications. Rarely do patients present with palpable lumps or nipple discharge due to early detection of lesions. Definitive diagnosis is made by core needle biopsy or stereotactic biopsy. The gold standard of treatment has become lumpectomy followed by external beam radiation. In advanced cases or large neoplasms, mastectomy is required. Radiotherapy added to surgery provides better outcomes with respect to recurrence, though overall survival remains similar. Chemotherapy in the form of tamoxifen and anti-HER2 drugs such as trastuzumab is a beneficial adjuvant therapy. With ongoing research and development of new drugs, as well as the better understanding about the pathogenesis of the condition, better and more effective modalities of treatment should soon become available.

References

- 1.Rosner D, Bedwani RN, Vana J. Noninvasive breast carcinoma. Results of a national survey by the American College of Surgeons. Ann Surg. 1980;192:139–147. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198008000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virnig BA, Tuttle TM, Shamliyan T, Kane RL. Ductal carcinoma in Situ of the breast: a systematic review of incidence, treatment, and outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(3):170–178. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinton LA, Sherman ME, Carreon JD, Anderson WF. Recent trends in breast cancer among younger women in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1643–1648. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernster VL, Ballard-Barbash R, Barlow WE, et al. Detection of ductal carcinoma in situ in women undergoing screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1546–1554. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.20.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.May DS, Lee NC, Richardson LC, Giustozzi AG, Bobo JK. Mammography and breast cancer detection by race and Hispanic ethnicity: results from a national program (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:697–705. doi: 10.1023/A:1008900220924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erbas B, Provenzano E, Armes J, Gertig D. The natural history of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97(2):135–144. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connell P, Pekkel V, Fuqua SA, Osborne CK, Clark GM, Allred DC. Analysis of loss of heterozygosity in 399 premalignant breast lesions at 15 genetic loci. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:697–703. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.9.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allred DC, Clark GM, Molina R, et al. Overexpression of HER-2/neu and its relationship with other prognostic factors change during the progression of in situ to invasive breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:974–979. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudas M, Neumayer R, Gnant MFX, Mittelbock M, Jakesz R, Reiner A. p53 Protein expression, cell proliferation and steroid hormone receptors in ductal and lobular in situ carcinomas of the breast. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:39–44. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(96)00368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerlikowske K, Molinari AM, Gauthier ML. Biomarker expression and risk of subsequent tumors after initial ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(9):627–637. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radisky DC, Santisteban M, Berman HK, et al. p16 INK4a expression and breast cancer risk in women with atypical hyperplasia. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4(12):1953–1960. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerlikowske K, Barclay J, Grady D, Sickles EA, Ernster V. Comparison of risk factors for ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:76–82. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Claus EB, Stowe M, Carter D. Breast carcinoma in situ: risk factors and screening patterns. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1811–1817. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.23.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, Storer BE, Remington PL. Risk factors for carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:697–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gapstur SM, Morrow M, Sellers TA. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer with a favorable histology: results of the Iowa Women’s Health Study. JAMA. 1999;281(22):2091–2141. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.22.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claus EB, Stowe M, Carter D. Family history of breast and ovarian cancer and the risk of breast carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;78:7–15. doi: 10.1023/A:1022147920262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allred DC. Ductal carcinoma in situ: terminology, classification, and natural history. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;41:134–138. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stomper PC, Connolly JL, Meyer JE, Harris JR. Clinically occult ductal carcinoma in situ detected with mammography: analysis of 100 cases with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1989;172:235–241. doi: 10.1148/radiology.172.1.2544922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ames V, Britton PD. Stereotactically guided breast biopsy: a review. Insights Imaging. 2011;2:171–176. doi: 10.1007/s13244-010-0064-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weaver DL, Vacek PM, Skelly JM, Geller BM. Predicting biopsy outcome after mammography: what is the likelihood the patient has invasive or in situ breast cancer? Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(8):660–673. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schouten van der Velden AP, Schlooz-Vries MS, Boetes C, Wobbes T. Magnetic resonance imaging of ductal carcinoma in situ: what is its clinical application? A review. Am J Surg. 2009;198(2):262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ernster VL, Barclay J, Kerlikowske K, Wilkie H, Ballard-Barbash R. Mortality among women with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in the population-based surveillance, epidemiology and end results program. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:953–958. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winchester DJ, Menck HR, Winchester DP. National treatment trends for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Arch Surg. 1997;132:660–665. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430300102020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faverly DR, Burgers L, Bult P, Holland R. Three dimensional imaging of mammary ductal carcinoma in situ: clinical implications. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1994;11:193–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vicini FA, Goldstein NS, Kestin LL. Pathologic and technical considerations in the treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast with lumpectomy and radiation therapy. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(8):883–890. doi: 10.1023/A:1008339113607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverstein MJ, Rosser RJ, Gierson ED, et al. Axillary lymph node dissection for intraductal breast carcinoma—is it indicated? Cancer. 1987;59:1819–1824. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870515)59:10<1819::AID-CNCR2820591023>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:478–488. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah C, McGee M, Wilkinson JB. Clinical outcomes using accelerated partial breast irradiation in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin Breast Cancer. 2012;12:259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Badruddoja M. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a surgical perspective. Int J Surg Oncol. 2012;2012:761364. doi: 10.1155/2012/761364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen L, Mayer JA, Krisko TI, et al. Inhibition of the p38 kinase suppresses the proliferation of human ER-negative breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69(23):8853–8861. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Zhang Y, Hill J, et al. The rexinoid LG100268 prevents the development of preinvasive and invasive estrogen receptor-negative tumors in MMTV-erbB2 mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(20):6224–6231. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crowe DL, Chandraratna RA. A retinoid X receptor (RXR)-selective retinoid reveals that RXR-alpha is potentially a therapeutic target in breast cancer cell lines, and that it potentiates antiproliferative and apoptotic responses to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(5):R546–R555. doi: 10.1186/bcr913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Schaid DJ, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(21):1633–1637. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.21.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakorafas GH, Farley DR. Optimal management of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Surg Oncol. 2003;12(4):221–240. doi: 10.1016/S0960-7404(03)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]