Abstract

Objectives

We sought to assess the impact of smoking status, cumulative pack-years, and time since cessation (the latter in former-smokers only) on three important domains of cardiovascular disease (CVD): inflammation, vascular dynamics and function, and subclinical atherosclerosis.

Approach and Results

The MESA cohort enrolled 6,814 adults without prior CVD. Smoking variables were determined by self-report and confirmed with urinary cotinine. We examined cross-sectional associations between smoking parameters and; 1) inflammatory biomarkers (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hsCRP], interleukin-6 [IL-6], and fibrinogen); 2) vascular dynamics and function (brachial flow-mediated dilation [FMD] and carotid distensibility by ultrasound, as well as aortic distensibility by MRI); and 3) subclinical atherosclerosis (coronary artery calcification [CAC], carotid intima-media thickness [CIMT], and ankle-brachial index [ABI]). We identified 3,218 never-smokers, 2,607 former-smokers, and 971 current-smokers. Mean age was 62 years and 47% were male. There was no consistent association between smoking and vascular distensibility or FMD outcomes. In contrast, compared to never-smokers, the adjusted association between current-smoking and measures of either inflammation or subclinical atherosclerosis was consistently stronger than for former-smoking (e.g. odds-ratio (OR) for hs-CRP > 2mg/L of 1.7 [95%CI, 1.5-2.1] Vs. 1.2 [1.1-1.4], OR for CAC > 0 of 1.8 [1.5-2.1] Vs. 1.4 [1.2-1.6], respectively). Similar associations were seen for IL-6, fibrinogen, CIMT, and ABI. A monotonic relationship was also found between increasing pack-years exposure and elevated inflammatory markers. Further, current smokers with hsCRP > 2mg/L were more likely to have increased CIMT, abnormal ABI, and CAC > 75th percentile for age, sex and race (relative to smokers with hsCRP < 2mg/L, interaction p < 0.05 for all three outcomes). In contrast, time since quitting in former-smokers was independently associated with lower inflammation and atherosclerosis (e.g. OR for hsCRP > 2mg/L of 0.91 [0.88-0.95] and OR for CAC > 0 of 0.94 [0.90-0.97] for every 5-year cessation interval).

Conclusion

These findings expand our understanding of the harmful effects of smoking and help explain the cardiovascular benefits of smoking cessation.

Keywords: Smoking, Inflammation, Atherosclerosis, Coronary Artery Calcium

Introduction

Cigarette smoking is a major reversible risk-factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD)1. Unfortunately, recent estimates suggest that approximately 20% of male and 16% of female U.S. adults continue to smoke2. While the mechanisms linking smoking to CVD are not fully known, smoking-induced vascular inflammation and subclinical vascular pathology are thought to play important roles in the development of subsequent clinical CVD outcomes3. These harmful effects may improve with smoking cessation4. Accordingly, it is important, particularly from a regulation science perspective, to determine which measures of subclinical vascular disease are most reflective of the negative impact of smoking in order to allow for timely evaluation of the impact of tobacco products, old and new5, on cardiovascular health. Similarly, determining whether any of the associations between smoking and these subclinical measures demonstrate reversibility with increased time since smoking cessation could suggest options to monitor vascular recovery post tobacco cessation.

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) is an extensively characterized, diverse, contemporary cohort, affording the opportunity to conduct a rigorous cross-sectional examination of the impact of smoking on three domains of pre-clinical CVD; inflammation, vascular dynamics and function, and subclinical-atherosclerosis. Specifically, we sought to determine the influence of smoking on these three CVD domains by testing the following; 1) the strength of association between smoking status and each domain; 2) whether these associations demonstrated a dose-response relationship with cumulative smoking exposure by quartiles of pack-years; and 3) whether these associations appear to attenuate with time since cessation in former smokers.

For the purposes of this analysis, inflammation was assessed using high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), fibrinogen and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Vascular dynamics (distensibility) was measured by both aortic MRI and carotid ultrasound, and vascular endothelial function was estimated by brachial artery flow-mediated dilation [FMD]). Finally, subclinical atherosclerosis was measured at three anatomically distinct vascular sites using carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT), coronary artery calcification (CAC), and ankle-brachial index (ABI). Thus, this study represents one of the most comprehensive analyses of the impact of smoking on subclinical vascular disease to date and is well positioned to inform regulatory policy around tobacco products.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Methods for this cross-sectional study are available in the online-only Data Supplement.

Results

Baseline Demographics

Results of the cotinine reclassification are displayed in Supplementary E-Table I. After reclassification, current-smokers comprised 971 (14%), former-smokers 2,607 (38%), and never-smokers 3,218 (47%) of MESA participants. Current-smokers were younger than never-smokers and were more likely to be male. Other baseline differences are shown in Table 1. The highest prevalence of current smoking was noted in African Americans and the lowest in Chinese Americans. Despite their younger age, mean (±SD) pack-years of smoking was higher in current-smokers (29.5 [±24.6]), as compared to former-smokers (21 [±25.2], p < 0.001). Among former-smokers, the mean (±SD) time elapsed between cessation and study enrollment was 22 (±13) years.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Cohort according to Smoking Status

| Never | Former | Current | P-Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=3218, 47% | N=2607, 38% | N=971, 14% | ||

| COVARIATES | ||||

| Male, N (%) | 1,161 (36) | 1,527 (59) | 517 (53) | <0.001 |

| Age, years | 62.2 (±10.5) | 63.4 (±9.9) | 58.4 (±9.1) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White, N (%) | 1,099 (34) | 1,182 (45) | 335 (35) | <0.001 |

| African-American, N (%) | 788 (25) | 728 (28) | 366 (38) | |

| Chinese-American, N (%) | 577 (18) | 173 (7) | 52 (5) | |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 754 (23) | 524 (20) | 218 (22) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher, N (%) | 1,188 (37) | 974 (37) | 231 (24) | <0.001 |

| Family History of MI, N (%) | 1,220 (38) | 1,090 (42) | 418 (43) | 0.002 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 127.0 (±21.9) | 127.1 (±20.9) | 123.7 (±21.4) | <0.001 |

| History of Hypertension, N (%) | 1,448 (45) | 1,233 (47) | 365 (38) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension Medication, N (%) | 1,208 (38) | 1,024 (39) | 294 (30) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 390 (12) | 347 (13) | 120 (12) | 0.71 |

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) | 89 (83–99) | 91 (83–100) | 89 (82–99) | 0.01 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 195.9 (±35.1) | 192.6 (±35.1) | 192.7 (±38.8) | 0.001 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 118.1 (±31.1) | 116.6 (±31.2) | 116.1 (±32.9) | 0.10 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 51.9 (±14.7) | 50.8 (±15.1) | 48.1 (±14.2) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 111 (79–161) | 109 (75–157) | 118 (84–171) | <0.001 |

| Lipid Medication, N (%) | 513 (16) | 476 (18) | 111 (11) | <0.001 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 28.1 (±5.5) | 28.7 (±5.5) | 28.1 (±5.3) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 63.7 (±9.6) | 62.5 (±9.7) | 63.1 (±9.5) | <0.001 |

| Current Alcohol Drinker, N (%) | 1,489 (46) | 1,609 (62) | 651 (67) | <0.001 |

| Percent (SD) of Calories from Alcohol | 1.5 (3.7) | 2.8 (5.0) | 3.4 (6.2) | <0.001 |

| Current Aspirin use, N (%) | 740 (23) | 756 (29) | 204 (21) | <0.001 |

| Current NSAID use, N (%) | 594 (16) | 491 (19) | 181 (19) | 0.01 |

| Current steroid use, N (%) | 47 (1.5) | 46 (1.8) | 12 (1.2) | 0.45 |

| Fever in past 2 weeks, N (%) | 64 (2.0) | 46 (1.8) | 34 (3.5) | 0.01 |

| Pack-year History, mean (SD) | ---- | 21.0 (±25.2) | 29.5 (±24.6) | <0.001 |

| CRUDE OUTCOMES | ||||

| hsCRP, mg/L | 1.78 (0.8–4.0) | 1.93 (0.8–4.2) | 2.50 (1.1–4.8) | <0.001† |

| IL-6, pg/ml | 1.13 (0.7–1.8) | 1.24 (0.8–1.9) | 1.33 (0.9–2.2) | <0.001† |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 350 (±74) | 341 (±72) | 352 (±76) | <0.001† |

| Carotid Distensibility‡, 10−3 mmHg | 2.46 (±1.07) | 2.45 (±1.06) | 2.81 (±1.13) | <0.001† |

| Aortic Distensibility‡, mmHg −1 | 1.90 (±1.35) | 1.77 (±1.20) | 1.81 (±1.08) | 0.011† |

| Brachial FMD‡, % | 4.54 (±2.92) | 4.22 (±2.84) | 4.33 (±2.69) | 0.014† |

| Internal cIMT, mm | 0.99 (±0.55) | 1.16 (±0.65) | 1.11 (±0.60) | <0.001† |

| CAC=0, number (%) | 1,797 (56) | 1,113 (43) | 494 (51) | <0.001† |

| CAC >75th centile‡, N (%) | 673 (47) | 706 (47) | 288 (60) | <0.001† |

| ABI <1.0, N (%) | 319 (10) | 287 (11) | 161 (17) | <0.001† |

Values are mean (±SD), median (25th–75th), or proportions (%).

In addition to standard P-values, for each crude outcome we also calculated P-values for trend calculated using a nonparametric test across ordered groups. All p values for linear trend are <0.001, except fibrinogen (p trend=0.25), aortic distensibility (p trend=0.20), and FMD (p trend=0.04).

All values are for entire study sample except for; Carotid Distensibility (n=6516 subjects), Aortic Distensibility (n=3530 subjects), FMD (n=3027 subjects). CAC percentiles were calculated in those with CAC>0 at baseline (n=3392) and are based on age and sex.

Smoking and Inflammation

Crude hsCRP levels was significantly higher in current-smokers than in never-smokers (median 2.5 mg/L versus 1.8 mg/L, P < 0.001) (Table 1). Median hsCRP in former-smokers was 1.9 mg/L. There were also linear trends of higher crude interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels in current- and former-smokers, compared to never-smokers (Table 1). However, no significant linear trend was seen between crude Fibrinogen levels and smoking status categories (p=0.25).

After full adjustment, current-smokers and former-smokers continued to demonstrate elevated hsCRP and IL-6 compared to never-smokers; with stronger relative associations for current-smokers (Table 2). For instance, compared to never-smokers, the odds of hsCRP ≥2mg/L was almost two-fold elevated for current-smokers (Odds Ratio [OR] of 1.8 [95% CI, 1.5, 2.1]). This contrasts with an OR of 1.2 (1.1, 1.4) for former-smokers. Adjusted fibrinogen levels were higher in current-smokers but lower in former-smokers, compared to never-smokers. Further adjustment for alcohol intake, recent fever, and anti-inflammatory medications (aspirin, NSAIDS, or steroids) did not alter the association between smoking and these inflammatory markers (Supplementary E-Table II).

Table 2.

Association of Smoking Status and Cessation Interval with Domains of CVD*

| Smoking Status | Cessation Interval | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never Smokers |

Former Smokers |

Current Smokers |

Former Smokers- 1-yr quit interval† |

Former Smokers- 5-yr quit interval‡ |

||

| Inflammation | ||||||

| hsCRP ≥2mg/L, Odds Ratio |

1 (ref) |

1.21 (1.06 to 1.37) |

1.75∥ (1.46 to 2.10) |

0.98∥ (0.97, 0.99) |

0.91∥ (0.88 to 0.95) |

|

| hsCRP, β–Coefficient ‡ |

0 (ref) |

0.08 (0.02 to 0.14) |

0.31∥ (0.23 to 0.38) |

−0.01∥ (−0.01 to −0.004) |

−0.04∥ (−0.06 to −0.02) |

|

| IL-6 , β–Coefficient ‡ |

0 (ref) |

0.06∥ (0.02 to 0.09) |

0.18∥ (0.14 to 0.23) |

−0.003 (−0.005, −0.001) |

−0.02 (−0.03 to −0.01) |

|

| Fibrinogen, β–Coefficient |

0 (ref) |

−5.60 (−9.16 to −2.04) |

8.06∥ (3.14 to 12.99) |

−0.09 (−0.30, 0.12) |

−0.47 (−1.53 to 0.60) |

|

| Vascular Function | ||||||

| Carotid Distensibility, β–Coefficient § |

0 (ref) | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.07) |

0.18∥ (0.12 to 0.23) |

0.002 (−0.001, 0.004) |

0.01 (−0.004 to 0.2) |

|

| Aortic Distensibility, β–Coefficient ‡, § |

0 (ref) | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.03) |

−0.05 (−0.10 to −0.01) |

−0.001 (−0.003, 0.002) |

−0.004 (−0.02 to 0.01) |

|

| Flow-Mediated Dilation, β–Coefficient § |

0 (ref) | 0.13 (−0.08 to 0.35) |

0.02 (−0.27 to 0.32) |

−0.001 (−0.01, 0.01) |

−0.01 (−0.08 to 0.06) |

|

|

Subclinical Atherosclerosis |

||||||

| cIMT, β–Coefficient |

0 (ref) |

0.05∥ (0.03 to 0.07) |

0.09∥ (0.06 to 0.12) |

−0.002 (−0.004, −0.001) |

−0.01 (−0.02 to −0.004) |

|

| CAC>0, Odds Ratio, |

1 (ref) |

1.38∥ (1.21 to 1.57) |

1.79∥ (1.49 to 2.14) |

0.98∥ (0.97, 0.99) |

0.94∥ (0.90 to 0.97) |

|

| CAC >75thcentile Odds Ratio § |

1 (ref) | 1.18 (0.99 to 1.41) |

1.38 (1.08 to 1.77) |

0.99 (0.98, 1.01) |

0.98 (0.93 to 1.02) |

|

| ABI<1, Odds Ratio |

1 (ref) |

1.24 (1.02 to 1.50) |

2.22∥ (1.74 to 2.83) |

0.98 (0.97, 0.99) |

0.91 (0.86 to 0.96) |

|

All values are expressed as Odds Ratios or β–Coefficients; with 95% confidence Intervals. Each robust linear and logistic model is adjusted for age, gender, race, MESA site, BMI, hypertension status, diabetes status, heart rate, LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides, treatment for dyslipidemia, family history of MI, and level of education.

For the cessation analysis, Beta-coefficients or Odds Ratios are presented per unit increase in smoking cessation interval (per year) and are also rescaled to each 5-year interval from smoking cessation.

Log-transformed

See Table 1 for sample sizes

Significant values (P<0.05) are presented in bold.

P-value <0.001

Similarly, adjusted hsCRP and IL-6 estimates increased in a monotonic fashion among higher quartiles of pack-year history (Table 3). These relative increases were more pronounced in current-smokers than in former-smokers, and all met statistical significance in the 4th quartile of pack-years compared to the 1st quartile. For example, the OR of hsCRP ≥2mg/L was 1.7 (1.3, 2.2) for former-smokers in the highest quartile of pack-years and 2.6 (1.7, 4.1) for current-smokers in the highest quartile of pack-years (both relative to the 1st quartile in each smoking category). Only current-smokers in the highest quartile of pack-years had relative increases in adjusted fibrinogen (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of Cumulative Smoke Exposure by pack-years with Domains of CVD *

| Former Smokers† | Current Smokers† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile | |

| 3–13 pack-years |

13–30 pack-years |

>30 pack-years |

11–24 pack-years |

24–42 pack-years |

>42 pack-years |

|

| Inflammation | ||||||

| hsCRP ≥2mg/L, Odds Ratio |

1.08 (0.84, 1.41) |

1.35 (1.04, 1.75) |

1.71∥ (1.31, 2.24) |

1.38 (0.90, 2.13) |

1.74 (1.14, 2.64) |

2.64∥ (1.67, 4.15) |

| hsCRP, β–Coefficient ‡ |

0.07 (−0.04, 0.19) |

0.14 (0.02, 0.25) |

0.23∥ (0.11, 0.35) |

0.08 (−0.12, 0.29) |

0.22 (0.01, 0.42) |

0.41∥ (0.19, 0.63) |

| IL-6 , β–Coefficient ‡ |

0.04 (−0.02, 0.11) |

−0.01 (−0.07, 0.07) |

0.08 (0.01, 0.15) |

0.07 (−0.04, 0.19) |

0.17 (0.05, 0.29) |

0.31∥ (0.18, 0.44) |

| Fibrinogen, β–Coefficient |

2.01 (−5.02, 9.05) |

−0.44 (−7.48, 6.60) |

−0.06 (−7.38, 7.26) |

12.73 (0.06, 25.40) |

7.25 (−7.46, 23.51) |

22.85∥ (9.24, 36.46) |

| Vascular Function | ||||||

| Carotid Distensibility, β–Coefficient § |

−0.03 (−0.11, 0.05) |

−0.01 (−0.10, 0.07) |

−0.02 (−0.10, 0.07) |

−0.11 (−0.27, 0.04) |

−0.06 (−0.23, 0.10) |

−0.02 (−0.19, 0.16) |

| Aortic Distensibility, β–Coefficient ‡ § |

0.01 (−0.07, 0.08) |

−0.03 (−0.11, 0.04) |

0.01 (−0.06, 0.09) |

−0.05 (−0.17, 0.07) |

−0.09 (−0.21, 0.03) |

0.06 (−0.08, 0.20) |

| Flow-Mediated Dilation, β–Coefficient § |

0.29 (−0.13, 0.72) |

−0.01 (−0.43, 0.40) |

0.19 (−0.23, 0.61) |

0.27 (−0.49, 1.04) |

0.70 (−0.05, 1.45) |

0.24 (−0.56, 1.05) |

|

Subclinical Atherosclerosis |

||||||

| cIMT, β–Coefficient |

0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) |

0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) |

0.04∥ (0.02, 0.05) |

0.02 (−0.01, 0.05) |

−0.02 (−0.04, 0.01) |

0.01 (−0.02, 0.04) |

| CAC>0, Odds Ratio |

1.56∥ (1.19, 2.04) |

1.66∥ (1.28, 2.17) |

1.98∥ (1.49, 2.62) |

1.65 (1.06, 2.58) |

1.71 (1.10, 2.66) |

1.47 (0.91, 2.36) |

| CAC >75thcentile Odds Ratio § |

1.13 (0.79, 1.62) |

1.09 (0.76, 1.56) |

1.23 (0.86, 1.76) |

0.66 (0.31, 1.38) |

0.67 (0.33, 1.38) |

0.84 (0.42, 1.67) |

| ABI<1, Odds Ratio |

0.99 (0.54, 1.83) |

1.64 (0.94, 2.84) |

2.73∥ (1.57, 4.75) |

3.47 (0.96, 12.48) |

3.29 (0.81, 13.27) |

2.64 (0.78, 8.96) |

All values are expressed as Odds Ratios or β–Coefficients; with 95% confidence Intervals. Each robust linear and logistic model is adjusted as per Table 2.

For each smoking status category, the reference group is the first quartile of pack-years in that category.

Log-transformed

See Table 1 for sample sizes

Significant values (P<0.05) are presented in bold.

P-value <0.001

The associations between smoking status and these three inflammatory biomarkers were qualitatively similar in males and females, with no evidence for interaction (with the single exception of higher fibrinogen levels in male smokers [p-interaction=0.01], Supplementary E-Table III). When stratified by ethnicity, the association between smoking status and hsCRP persisted in Whites and African-Americans. In contrast, this association was less significant in Chinese-American and Hispanics (Supplementary E-Table IV). However, there was no evidence that ethnicity modified the effect of smoking status on hsCRP levels overall (interaction p=0.89).

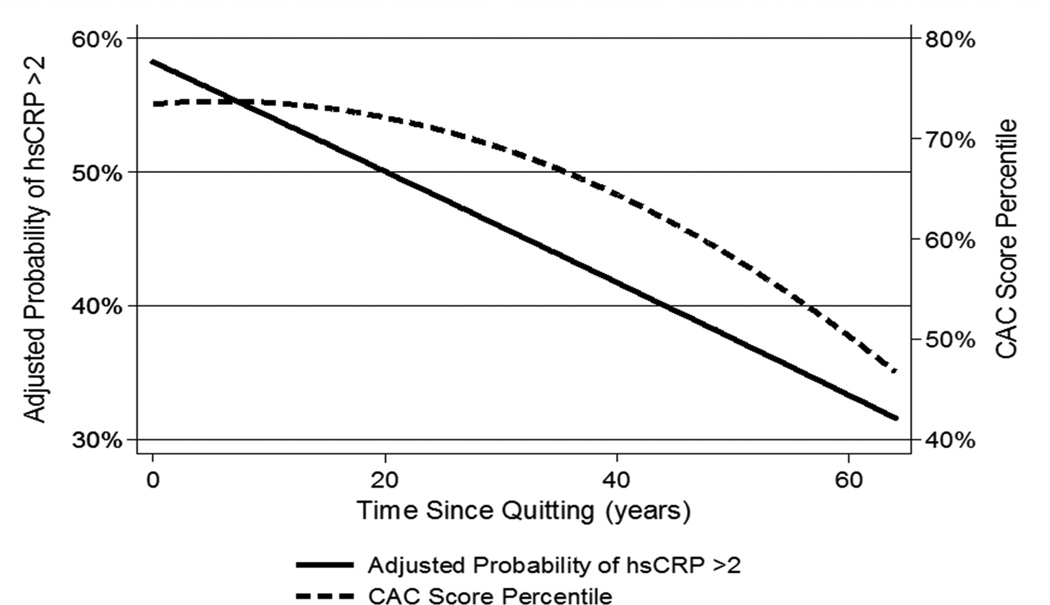

Further, for every 5-year period that had passed between smoking cessation and the baseline MESA assessment, former-smokers tended to have lower hsCRP levels (e.g. OR of 0.91 [0.88-0.95] for hsCRP ≥2mg/dl, Table 2, Figure 1). Notably, there was a negative correlation between smoking cessation interval and pack-years exposure in former-smokers (Spearman’s correlation coefficient of −0.47, p < 0.001). Nonetheless, the smoking cessation interval OR for hsCRP ≥2mg/dl was essentially unchanged in a sensitivity analysis performed with pack-years further added to the fully adjusted Table-2 model as a continuous variable (OR of 0.92 [0.88, 0.96], Supplementary E-Table V). Therefore, to illustrate further, former-smokers with 15 years of cessation prior to the baseline MESA visit had an 8-9% lower odds of having hsCRP > 2mg/dL at baseline, compared to former-smokers who were abstinent for 10 years. Lower relative IL-6 levels were also present per 5-year cessation interval, a finding that was also robust to further adjustment for pack-years in the model (Table 2, Supplementary E-Table V). However, years since cessation was not associated with lower Fibrinogen.

Figure 1. Association of time since quitting with subsequent hsCRP and CAC levels in former smokers.

Adjusted for age, gender, race, MESA site, BMI, hypertension status, diabetes status, heart rate, LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides, treatment for dyslipidemia, family history of MI, and level of education.

CAC= Coronary Artery Calcium (percentile is for age, sex and race), hsCRP=high-sensitivity C-Reactive Protein

Smoking and Vascular Dynamics and Function

In the representative MESA sub-samples who underwent aortic MRI and FMD testing, the proportion of current-smokers was identical to the overall analysis sample (Supplementary E-Table VI). In crude (Table 1) and adjusted (Table 2) analyses, carotid distensibility was higher in current-smokers compared to never- and former-smokers. In contrast, aortic distensibility was lower in former- and current-smokers compared to never-smokers. After adjustment, there were no significant differences in brachial FMD among any of the smoking status categories. Stratification by pack-years cumulative smoking exposure did not influence these null associations (Table 3). Further, neither age nor gender modified the effect of smoking on any of these three outcomes (p-interaction for all > 0.05). In addition, time-since cessation in former-smokers was not associated with differences in vascular dynamics or function within the MESA cohort (Table 2).

Smoking and Subclinical Atherosclerosis

Both smoking groups had higher crude and adjusted internal cIMT compared to never-smokers. We found similar relationships for CAC (Tables 1 and 2). For example, current-smokers were more likely than never-smokers to have a CAC score > 75th percentile for age, sex and race (adjusted OR 1.38 [1.08, 1.77]), however, the association for former-smokers was weaker (adjusted OR 1.18 [0.99, 1.41], Table 2). While both former-smokers and current-smokers demonstrated higher odds of CAC > 0 compared to never-smokers, the association was again stronger in current-smokers. Similar crude and adjusted associations were also demonstrated for reduced ABI. Further adjustment for alcohol intake, recent fever, or anti-inflammatory medications did not appreciably change any of these results (Supplementary E-Table II).

When stratified by pack-year cumulative exposure, only former-smokers in the highest quartile of pack-years had increased cIMT (Table 3). There was also a graded increase in odds for CAC > 0 in former-smokers with higher cumulative smoking exposure (OR of 1.6 for 2nd quartile of pack-years, 1.7 for 3rd quartile and 2.0 for the 4th quartile, all compared to 1st quartile). A similar association was also seen for reduced ABI (Table 3). In contrast to former smokers, associations between pack-year quartiles and subclinical atherosclerosis were mostly null in current-smokers.

The above associations between smoking status and the presence of CAC were generally similar when stratified by ethnicity. As with hsCRP, associations appeared weaker for Chinese Americans (Supplementary E-Table IV). However, once again, there was no evidence for effect modification by ethnicity (interaction p=0.92 for OR CAC > 0 by smoking status). Similarly, there was no consistent evidence that gender modified the effect of smoking on these subclinical atherosclerosis measures (Supplementary E-Table III).

The time interval between the onset of smoking cessation and subsequent testing at the baseline MESA visit was also associated with reduced burden of subclinical-atherosclerosis in former-smokers, both by year since cessation and rescaled to intervals of 5-years since cessation (Table 2, figure 1). For example, the OR for CAC > 0 was 0.94 (95% CI 0.90, 0.97) and the OR for ABI < 1 was 0.91 (0.86, 0.96) per 5-year interval of abstinence in former-smokers. In contrast to the findings for hs-CRP, a sensitivity analysis demonstrated that addition of pack-years exposure as a continuous variable in the fully adjusted model led to mild attenuation in the beneficial impact of 5-year cessation interval on risk for baseline CAC > 0 (OR 0.97 [0.92, 1.01]), ABI < 1 (OR 0.95 [0.89, 1.01], and cIMT, Supplementary E-Table V).

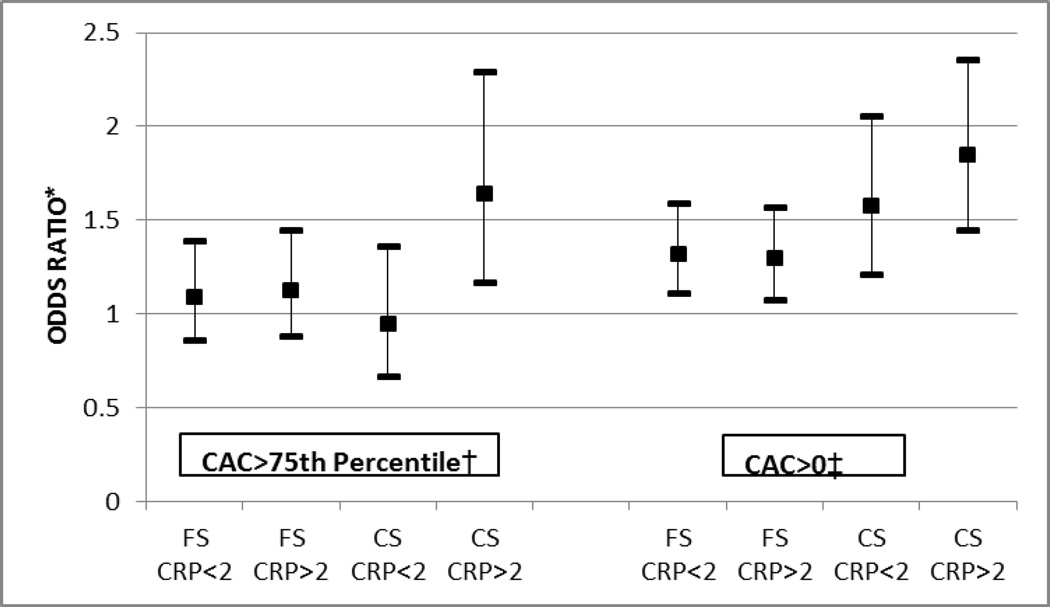

Atherosclerosis in smokers with and without inflammation (testing effect modification)

While smoking status was associated with CAC overall, Figure 2 shows that smokers with hsCRP levels ≥2mg/L were more likely to have relatively higher adjusted CAC than smokers without inflammation. This trend persisted after further adjustment for pack-years (Supplementary E-Table VII). Of note, both former-smokers and current-smokers had an increased odds for CAC > 0 (compared to never-smokers), whether or not hsCRP was ≥2mg/L. However, the point estimates increased monotonically in each of the 4 groups, ranging from former-smokers without inflammation to current-smokers with inflammation (Figure 2). In contrast, only current-smokers with active inflammation were at risk for CAC levels greater than the 75th percentile for age, sex, and race (OR 1.6 [1.2, 2.3]). Indeed inflammation appeared to modify the effect of smoking on the likelihood of severe CAC > 75th percentile (interaction p value=0.01, figure 2); but not for milder disease (interaction p=0.20 for CAC > 0). Further, we also found evidence that elevated inflammatory markers also adversely modify the effect of smoking on both cIMT severity (interaction p=0.02) and on ABI <1 (interaction p=0.004) [Supplementary E-Table VIII].

Figure 2. Association of Smoking with Coronary Calcium, based on Inflammatory Status (see also Supplementary E-Table VII.

*All Odds Ratios are compared to Never Smokers with hsCRP<2mg/L. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Logistic model is adjusted for age, gender, race, MESA site, BMI, hypertension status, diabetes status, heart rate, LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides, treatment for dyslipidemia, family history of MI, and level of education.

†Interaction of hsCRP on smoking status and CAC > 75th centile p= 0.01

‡Interaction of hsCRP on smoking status and CAC > 0 p=0.20.

CAC > 75th %= Coronary artery calcium greater than the 75th percentile for age, sex and race, CAC > 0 AU= Coronary Artery Calcium greater than zero Agatston Units, FS=Former Smokers, CS=Current Smokers, hsCRP=high-sensitivity C-Reactive Protein

Discussion

In this multi-ethnic cohort free of known CVD, both former and current smoking status were independently associated with markers of inflammation and subclinical atherosclerosis. These cross-sectional associations were stronger for current-smokers than for former-smokers. In addition, there was evidence of a graded increase in association between higher levels of cumulative tobacco exposure and markers of inflammation. These findings were statistically similar among gender and ethnicity categories. Smokers with elevated inflammatory markers were also more likely to have an increased burden of subclinical atherosclerosis and, importantly, we extend prior knowledge by demonstrating significant interaction for inflammation (specifically elevated hsCRP) on the association between smoking status and measures of subclinical atherosclerosis at all three anatomically distinct sites. In the context of established data supporting a causal role for smoking in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, this interaction is strongly suggestive of effect modification. However, none of the smoking parameters evaluated were consistently associated with adverse markers of vascular dynamics and function.

This analysis is one of the first to comprehensively focus on the interplay of smoking parameters and three diverse domains of vascular disease: inflammation, vascular dynamics and function, and subclinical atherosclerosis. In addition, while prior cohort studies have been ethnically homogenous, our data derive from a rigorously conducted, well-characterized, community-based, multi-ethnic cohort. Similarly, by utilizing available urinary cotinine where possible (see methods supplement for details), we minimized misclassification (and reporting bias) of the smoking exposure variables. We believe that our findings have important implications for tobacco regulatory science by shedding light on those measures of subclinical cardiovascular disease that are most reflective of the effect of smoking in order to facilitate evidence based, efficient, and timely evaluation of new tobacco products on cardiovascular health.

In addition, our results also provide new insights into the impact of smoking cessation on CVD. Specifically, the association between smoking and inflammation, and to a lesser extent smoking and atherosclerosis, both attenuate with years since cessation in former smokers, providing supporting evidence for the beneficial cardiovascular effects of smoking cessation. These results also suggest potential opportunities for monitoring the response of smoking cessation on vascular health.

Smoking and inflammation

The emerging risk factors collaboration (ERFC) reported that hsCRP levels were 37% (95% CI, 31-44%) higher in current- compared to never-smokers6. Our results confirm these findings by demonstrating that both current- and former-smoking status are independently associated with elevated hsCRP in this multiethnic sample. Moreover, we determined that these independent associations were incrementally stronger in the highest quartile of pack-years cumulative smoke exposure. In such, our data confirm prior studies suggesting an association between cumulative smoke exposure and hsCRP7.

Further, we extend prior reports by studying more ‘proximal’ inflammatory markers which are thought to activate earlier in the inflammatory cascade than hsCRP. Fibrinogen is a pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic marker, and has been correlated with increased CVD risk8. Soluble IL-6 has also been associated with increased CVD9–11. We add to prior data by demonstrating an association between both smoking status and cumulative smoking exposure with IL-6. Results for fibrinogen were less consistent.

Finally, we found that the associations with hsCRP and IL-6 are weaker for former- compared to current-smokers, and that they further attenuate with increased time since quitting in former-smokers. Reichert et al previously reported that smoking cessation led to immediate reductions in ‘proximate’ markers of inflammation12. However, previous population studies have suggested that more ‘distal’ markers (e.g. hsCRP) can take up to 5 years to improve13. An analysis from NHANES found an improvement in hsCRP levels 5 years after smoking cessation14. However, in MESA, our results suggest there may be small but statistically significant reductions in both hsCRP and IL-6 after just one year relative difference in smoking cessation (with cessation time modeled as a continuous variable). While this result is based on a statistical model of cross sectional data, and will therefore require replication, our results suggest that hsCRP may be useful in monitoring the acute effects of smoking cessation on vascular health.

Smoking and Vascular Dynamics and Function

The lack of a consistent association between smoking and either vascular distensibility (by both aortic MRI and carotid ultrasound) or endothelial function (brachial FMD) was an unexpected finding. Indeed, previous studies have suggested that smoking is associated with FMD in a dose-dependent manner15. Prior studies have also reported improved endothelial function by FMD in smokers who successfully maintain abstinence one year after cessation4. In addition, smoking has been previously associated with measures of pulsatile arterial function and stiffness16, an effect which may also be reversible17.

However, with a mean age of 62 years, our sample was older than prior FMD-smoking studies4, 15. It is well known that endothelial and vascular function deteriorates with age18, and it is possible that the adverse effect of smoking on FMD is attenuated in older subjects. For example, a prior MESA analysis has shown that the effect of particulate matter on FMD is attenuated in older subjects19. However, despite these considerations, we found no statistical interaction by age in our models.

While we confirm the results of prior arterial distensibility data, demonstrating that current smoking is associated with increased carotid distensibility20, we found no association with pack-years exposure. In addition, we found that current smoking had the reverse association in the aorta, with evidence for reduced distensibility at this site. While these findings are hypothesis-generating, they suggest that either the endothelial dysfunction or the fragmentation of elastin seen in smokers may be regional in nature. Further, recent data suggest that smoking is associated with higher central aortic pressures that could, over time, reduce local aortic distensibility21. As pulse-pressure differed between smoking groups, we also conducted sensitivity analyses further adjusting for pulse-pressure. This did not change the above findings (data not shown).

Smoking and Subclinical atherosclerosis

Prior reports from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study have established that increased cIMT is common amongst current-smokers22. Similar cIMT findings have also been reported from other cohorts. 20, 23, 24 Our study adds to these data by suggesting that there may be relative reductions in cIMT severity as duration of cessation in former-smokers increases.

A significant relationship between smoking and CAC has also previously been reported in MESA25, as well as other analyses26. However, prior data have not explored the association between CAC and cumulative exposure by pack-years of smoke exposure. MESA provides an opportunity to test this and, indeed, we found that former-smokers in the highest quartile of pack-years have approximately twice the odds of having any CAC, compared to the lowest quartile. However, the negative correlation between cessation interval and pack-years suggests that those former-smokers in the lowest quartile of pack-years were also more likely to have the largest cessation interval. In addition, for current-smokers, the relative impact of pack-years exposure was not consistent. This finding may relate to a number of considerations; 1) Cumulative exposure to tobacco may not be an important risk factor for atherosclerosis in persons who are actively smoking as opposed to those who are not, 2) former smokers are older than current smokers with more time elapsed since initial smoking exposure (allowing differences in subclinical atherosclerosis to manifest, in contrast to the more immediate effect inflammatory markers), and 3) the sample size in the current smoking group may not afford adequate power to detect differences by cumulative exposure.

Importantly, we also found evidence that the association between smoking and CAC may attenuate with time since cessation in former-smokers. For example, for every 5 years of abstinence, the independent odds of having any CAC were reduced by approximately 6%. These data support the hypothesis that smoking cessation prevents the development of incident CAC27. Similar trends were seen for cIMT and for ABI, a marker of more advanced atherosclerosis. However, these results were not as robust as those for the inflammatory markers, as we found that the beneficial association between increasing cessation interval and prevalent reductions in atherosclerosis markers were marginally attenuated when our model was further adjusted for pack-years as a potential confounder (Supplementary E-Table V). Nonetheless, taken together, these results are supportive of the hypothesis that time since cessation in former smokers may be associated with lower relative burdens of subclinical atherosclerosis.

Finally, we extend our understanding of smoking induced vascular disease by testing for statistical interaction between smoking status, inflammation, and all three of our subclinical atherosclerosis outcomes (cIMT, CAC, and ABI). For example, we found that current-smokers with hsCRP≥2mg/L were almost twice as likely to have any CAC as never-smokers without evidence of inflammation. Our results add to prior data from the Cardiovascular Health Study demonstrating that hsCRP is strongly related to both smoking exposure and atherosclerosis burden (measured in that study by ABI)7. However, by demonstrating statistical interaction for all our subclinical atherosclerosis outcomes, we report compelling and robust new evidence that inflammation may biologically modify the systemic effect of smoking on subclinical atherosclerosis.

Limitations

Due to the cross-sectional nature of this analysis, the temporal sequence cannot be determined. Thus, while the causal role of smoking in CVD is widely accepted, our data cannot be presumed to reflect causal effects. In addition, because these mechanistic cross-sectional data are hypothesis generating in nature, they will require replication and we have presented confidence intervals throughout and neither directly reported p-values in our models (except for interaction testing) nor performed adjustments for multiple testing. However, for reference purposes, we did identify results that meet a significance level of both p < 0.05 and p < 0.001 (the latter satisfying Bonferroni correction). We did not exclude persons with hs-CRP ≥10mg/L from the main analyses (levels above this may reflect acute inflammation) 28, however sensitivity analyses excluding individuals with hs-CRP above this threshold demonstrated only marginal attenuation in our results suggesting that acute inflammation is not driving the associations between smoking and the inflammatory biomarkers (Supplementary E-Table IX). Given FMD and cardiac MRI were performed in subsets of the entire sample, it is possible that selection bias could influence the results related to these imaging tests. However, per MESA protocol, subjects undergoing such imaging did not differ significantly from those who did not (Supplementary E-Table IV)29, 30. In addition, Cotinine was only available in a subset of 3,965 MESA participants (see methods and Supplementary E-Table I). However, these persons were chosen at random in order to eliminate bias. To test the robustness of our findings, we also repeated the entire analysis using self-reported smoking alone as the exposure variable throughout (i.e. those with cotinine measurements were not reclassified). The results of this analysis were quantitatively and qualitatively similar to the results presented above (data not shown). Finally, as this study is cross-sectional, demonstrating reduced odds for inflammation or CAC with increasing time elapsed since smoking cessation in the past does not mean that the markers are “falling” over time in formers-smokers, rather that former-smokers who give up smoking earlier are more likely to have normal values of these markers at assessment in the future.

Conclusion

In this multi-ethnic study, current-smoking status and cumulative exposure were more strongly associated with inflammation and subclinical-atherosclerosis than former- or never-smoking. While smoking did not appear to influence vascular dynamics and function in this older cohort, subclinical atherosclerosis appeared most severe in those smokers with concomitant elevations in inflammatory markers, with evidence supporting effect modification. These associations attenuated with time since quitting in former smokers. In sum, this study provides insights into mechanisms by which smoking leads to CVD, supporting the link between smoking, inflammation and atherosclerosis. Our findings also help to explain the cardiovascular benefit of smoking cessation and suggest potential strategies for monitoring both the harm of new tobacco products and the benefits of smoking cessation on vascular health.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Results from this well characterized multi-ethnic cohort provide comprehensive new epidemiological data on the impact of smoking on vascular disease. The authors demonstrate that both smoking status and cumulative exposure by pack-years impact multiple inflammatory biomarkers. In addition, smoking status is associated with elevations in measures of subclinical atherosclerosis in a number of different vascular beds, with more pronounced relative abnormalities in atherosclerosis burden in current-smokers than in former-smokers. Higher cumulative smoking exposure (by pack-year history) was also associated with increased subclinical atherosclerosis in former smokers. Importantly, the authors extend prior work by demonstrating that all of these associations attenuated with increased time since quitting in former smokers, thereby suggesting potential strategies to monitor vascular health post cessation. Furthermore, inflammation (measured as hsCRP≥2mg/L) adversely modified the impact of smoking on a number of subclinical atherosclerosis markers imaged in different vascular beds. In contrast, in this older multiethnic sample, smoking did not reliably influence measures of vascular dynamics and function (e.g. arterial distensibility or flow mediated dilation). These findings have important implications for tobacco regulatory science that may allow for evidence based, efficient, and timely evaluation of new tobacco products on cardiovascular health.

Acknowledgements

We thank the other investigators, staff, and participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions.

Sources of funding: This analysis was supported by funding from the American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center (A-TRAC, NIH 1 P50 HL120163-01), a member of the FDA Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science for Research Relevant to the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (P50). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration. The MESA study which supplied the data for this analysis was supported by contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95167 and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The cotinine measurement was supported by contract R01-HL077612. Dr McEvoy is supported by the Pollin Cardiovascular Prevention Fellowship.

Abbreviations

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease events

- HsCRP

high-sensitivity C-Reactive Protein

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- CAC

Coronary artery calcium

- CIMT

Carotid Intima-media Thickness

- ABI

Ankle-Brachial Index

- FMD

Flow-Mediated Dilation

Footnotes

Supplementary information is provided in an Online Appendix.

Disclosures: Dr Budoff serves on a speakers’ bureau for GE Healthcare. The remaining authors have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.The health consequences of smoking-50 years of progress: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta (GA): 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Executive summary: Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2014;129:399–410. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000442015.53336.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: An update. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004;43:1731–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson HM, Gossett LK, Piper ME, Aeschlimann SE, Korcarz CE, Baker TB, Fiore MC, Stein JH. Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on endothelial function: 1-year outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;55:1988–1995. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes: A scientific review. Circulation. 2014;129:1972–1986. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.007667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Lowe G, Pepys MB, Thompson SG, Collins R, Danesh J Emerging Risk Factors C. C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: An individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:132–140. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61717-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tracy RP, Psaty BM, Macy E, Bovill EG, Cushman M, Cornell ES, Kuller LH. Lifetime smoking exposure affects the association of c-reactive protein with cardiovascular disease risk factors and subclinical disease in healthy elderly subjects. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 1997;17:2167–2176. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danesh J, Lewington S, et al. Fibrinogen Studies C. Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: An individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:1799–1809. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.14.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biasucci LM, Vitelli A, Liuzzo G, Altamura S, Caligiuri G, Monaco C, Rebuzzi AG, Ciliberto G, Maseri A. Elevated levels of interleukin-6 in unstable angina. Circulation. 1996;94:874–877. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danesh J, Kaptoge S, Mann AG, Sarwar N, Wood A, Angleman SB, Wensley F, Higgins JP, Lennon L, Eiriksdottir G, Rumley A, Whincup PH, Lowe GD, Gudnason V. Long-term interleukin-6 levels and subsequent risk of coronary heart disease: Two new prospective studies and a systematic review. PLoS medicine. 2008;5:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarwar N, Butterworth AS, et al. Collaboration IRGCERF. Interleukin-6 receptor pathways in coronary heart disease: A collaborative meta-analysis of 82 studies. Lancet. 2012;379:1205–1213. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61931-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reichert V, Xue X, Bartscherer D, Jacobsen D, Fardellone C, Folan P, Kohn N, Talwar A, Metz CN. A pilot study to examine the effects of smoking cessation on serum markers of inflammation in women at risk for cardiovascular disease. Chest. 2009;136:212–219. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wannamethee SG, Lowe GD, Shaper AG, Rumley A, Lennon L, Whincup PH. Associations between cigarette smoking, pipe/cigar smoking, and smoking cessation, and haemostatic and inflammatory markers for cardiovascular disease. European heart journal. 2005;26:1765–1773. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakhru A, Erlinger TP. Smoking cessation and cardiovascular disease risk factors: Results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. PLoS medicine. 2005;2:e160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Georgakopoulos D, Bull C, Thomas O, Robinson J, Deanfield JE. Cigarette smoking is associated with dose-related and potentially reversible impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation in healthy young adults. Circulation. 1993;88:2149–2155. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Comparison of the measures of pulsatile arterial function between asymptomatic younger adult smokers and former smokers: The bogalusa heart study. American journal of hypertension. 2006;19:897–901. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu-Jie W, Hui-Liang L, Bing L, Lu Z, Zhi-Geng J. Impact of smoking and smoking cessation on arterial stiffness in healthy participants. Angiology. 2013;64:273–280. doi: 10.1177/0003319712447888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Spiegelhalter DJ, Georgakopoulos D, Robinson J, Deanfield JE. Aging is associated with endothelial dysfunction in healthy men years before the age-related decline in women. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1994;24:471–476. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishnan RM, Adar SD, Szpiro AA, Jorgensen NW, Van Hee VC, Barr RG, O'Neill MS, Herrington DM, Polak JF, Kaufman JD. Vascular responses to long- and short-term exposure to fine particulate matter: Mesa air (multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis and air pollution) Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;60:2158–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharrett AR, Ding J, Criqui MH, Saad MF, Liu K, Polak JF, Folsom AR, Tsai MY, Burke GL, Szklo M. Smoking, diabetes, and blood cholesterol differ in their associations with subclinical atherosclerosis: The multiethnic study of atherosclerosis (mesa) Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markus MR, Stritzke J, Baumeister SE, et al. Effects of smoking on arterial distensibility, central aortic pressures and left ventricular mass. International journal of cardiology. 2013;168:2593–2601. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richey Sharrett A, Coady SA, Folsom AR, Couper DJ, Heiss G, Study A. Smoking and diabetes differ in their associations with subclinical atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease-the aric study. Atherosclerosis. 2004;172:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raitakari OT, Juonala M, Kahonen M, Taittonen L, Laitinen T, Maki-Torkko N, Jarvisalo MJ, Uhari M, Jokinen E, Ronnemaa T, Akerblom HK, Viikari JS. Cardiovascular risk factors in childhood and carotid artery intima-media thickness in adulthood: The cardiovascular risk in young finns study. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:2277–2283. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baldassarre D, Castelnuovo S, Frigerio B, Amato M, Werba JP, De Jong A, Ravani AL, Tremoli E, Sirtori CR. Effects of timing and extent of smoking, type of cigarettes, and concomitant risk factors on the association between smoking and subclinical atherosclerosis. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40:1991–1998. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kronmal RA, McClelland RL, Detrano R, Shea S, Lima JA, Cushman M, Bild DE, Burke GL. Risk factors for the progression of coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic subjects: Results from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (mesa) Circulation. 2007;115:2722–2730. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.674143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rasmussen T, Frestad D, Kober L, Pedersen JH, Thomsen LH, Dirksen A, Kofoed KF. Development and progression of coronary artery calcification in long-term smokers: Adverse effects of continued smoking. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;62:255–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jockel KH, Lehmann N, Jaeger BR, Moebus S, Mohlenkamp S, Schmermund A, Dragano N, Stang A, Gronemeyer D, Seibel R, Mann K, Volbracht L, Siegrist J, Erbel R. Smoking cessation and subclinical atherosclerosis--results from the heinz nixdorf recall study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: Application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the centers for disease control and prevention and the american heart association. Circulation. 2003;107:499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heckbert SR, Post W, Pearson GD, Arnett DK, Gomes AS, Jerosch-Herold M, Hundley WG, Lima JA, Bluemke DA. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors in relation to left ventricular mass, volume, and systolic function by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: The multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;48:2285–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeboah J, Folsom AR, Burke GL, Johnson C, Polak JF, Post W, Lima JA, Crouse JR, Herrington DM. Predictive value of brachial flow-mediated dilation for incident cardiovascular events in a population-based study: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2009;120:502–509. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.864801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.