Abstract

The peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR) γ is a member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors. Thiazolidinediones, pharmacological ligands for PPARγ, are currently used in the management of type 2 diabetes. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ is expressed in the lung and pulmonary vasculature, and its expression is reduced in the vascular lesions of patients with pulmonary hypertension. Furthermore, thiazolidinedione PPARγ ligands reduced pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling in several experimental models of pulmonary hypertension. This report reviews current evidence that PPARγ may represent a novel therapeutic target in pulmonary hypertension and examines studies that have begun to elucidate mechanisms that underlie these potential therapeutic effects.

Keywords: PPARγ, pulmonary hypertension, nitric oxide, NADPH oxidase

Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors (PPARs) are ligand-activated transcription factors belonging to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily.1 Although limited evidence suggests that the PPARα and PPARβ/δ receptors may play a role in regulation of pulmonary vascular function, this report focuses on rapidly expanding evidence that PPARγ regulates pulmonary vascular function and that activating ligands can modulate derangements of pulmonary vascular dysfunction that contribute to disease pathogenesis. Transcriptional activation of the PPARγ receptor requires heterodimerization with the retinoid receptor, retinoid X receptor (RXR).2 Activation of the receptor is promoted by structurally diverse ligands including thiazolidinediones (TZDs) and long-chain fatty acids and their metabolites. Among these ligands, the synthetic TZD class, including rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, has been used for clinical benefit in patients with type 2 diabetes where these medications enhance insulin sensitivity and reduce metabolic derangements. As reviewed earlier, the activated PPARγ/RXR heterodimer binds to PPAR response elements in the promoter region on responsive genes to modulate their transcriptional activity. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ activation can promote enhanced expression of responsive genes or can lead to reductions in gene expression through transrepression mechanisms. As a result, PPARγ activation can lead to both the enhancement and reduction in the expression level of target genes in a broad variety of tissues.3 Emerging evidence indicates that PPARγ activation may exert salutary effects in a variety of disease processes. This review focuses on the role of PPARγ in pulmonary vascular biology and recent developments suggesting that the PPARγ receptor may represent a novel therapeutic target in pulmonary vascular disease.

Pulmonary hypertension, the most common manifestation of pulmonary vascular disease, can be defined as a mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than 25 mm Hg at rest or greater than 30 mm Hg with exercise. Pulmonary hypertension accounts for approximately 16,000 deaths per year in the United States and has been reported to result in 260,000 hospitalizations per year in this country.4 It is most commonly caused by diverse clinical conditions that produce chronic continuous or intermittent alveolar hypoxia. Current concepts indicate that the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension is related to pulmonary vasoconstriction, vascular remodeling, and proliferation of cells in the wall of the pulmonary vasculature including smooth muscle and endothelial cells. Existing treatment strategies for pulmonary hypertension are limited by their high cost and relative lack of efficacy and by an incomplete understanding of the pathogenesis of this disorder. Collectively, these observations indicate that pulmonary hypertension is an all-too-common disorder for which novel and more effective therapeutic strategies are urgently needed.

The rationale for considering the role of PPARγ ligands in pulmonary hypertension stems from several lines of evidence. First, considerable literature demonstrates that thiazolidinedione ligands for the PPARγ receptor have vascular benefit within the systemic vasculature of patients and experimental animals without diabetes. For example, in the apolipoprotein E (ApoE)– or LDL receptor–deficient mouse models of atherosclerosis, TZDs have been shown to reduce impaired endothelial function and to attenuate the development of atherosclerotic lesions.5–7 In human subjects, TZDs reduce common carotid artery intima-media thickness, improve endothelium-dependent vasodilation, and reduce serum inflammatory markers.8–13 These studies suggest that PPARγ ligands can exert significant vascular effects independent of their ability to modulate metabolic derangements in diabetes.

Furthermore, a seminal publication in 2003 provided direct evidence that alterations in PPARγ function may be involved in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension.14 In this study, PPARγ expression was examined in the pulmonary vasculature of lungs from normal controls and from patients with primary and secondary forms of pulmonary hypertension. The levels of immunoreactive PPARγ in specimens from patients with primary and secondary forms of pulmonary hypertension were reduced compared with controls or with patients with other forms of chronic lung disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ was also reduced in the vascular lesions of rats with severe pulmonary hypertension caused by treatment with hypobaric hypoxia and a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor antagonist. Reductions in PPARγ were related to shear stress: exposing the endothelial-like ECV304 cell line to shear stress in vitro reduced PPARγ protein levels. Furthermore, ECV304 cells expressing a dominant-negative PPARγ formed reticular tubelike structures in 3-dimensional collagen gels and produced intravascular tumors when injected into the tail vein of nude mice. This study provided the first evidence that shear stress might reduce PPARγ and that reduced PPARγ expression was observed in animal and human subjects with pulmonary hypertension. These investigators speculated that increases in vascular shear stress in the lungs of subjects with pulmonary hypertension could reduce PPARγ expression leading to enhanced cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, events that could thereby contribute to the pathogenesis of pulmonary vascular remodeling and progressive increases in pulmonary hypertension.

Whereas the study by Ameshima and colleagues14 demonstrated a putative role for reductions in PPARγ expression in pulmonary hypertension, Matsuda and coworkers15 provided the first evidence that stimulation of the PPARγ receptor might attenuate pulmonary hypertension. These investigators used a rat model of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Monocrotaline is a pyrrolizidine alkaloid phytotoxin used experimentally to cause a pulmonary vascular syndrome in rats characterized by proliferative pulmonary vasculitis and pulmonary hypertension.16 Matsuda et al15 demonstrated that injection of monocrotaline caused pulmonary vascular remodeling, pulmonary hypertension, and enhanced vascular staining for proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Treatment for 3 weeks with the TZD ligands, pioglitazone or troglitazone, reduced pulmonary hypertension, vascular wall thickening, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen staining. Collectively, these findings provided novel evidence that PPARγ ligands inhibited monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling by suppressing cellular proliferation.

The ability of PPARγ ligands to attenuate pulmonary hypertension was further supported by a recent report by Crossno and colleagues.17 In these studies, pulmonary hypertension was induced in rats by exposure to continuous hypoxia for 3 weeks. Hypoxia produced significant increases in pulmonary vascular remodeling measured as the ratio of wall thickness to lumen radius. Animals treated with rosiglitazone (5 mg/kg per day incorporated into the diet) for the 3-week duration of hypoxia exposure demonstrated no pulmonary vascular remodeling. Furthermore, initiation of rosiglitazone treatment after exposure to hypoxia for 14 days and the generation of pulmonary hypertension reduced pulmonary vascular remodeling, suggesting that PPARγ ligands could not only attenuate the development of pulmonary hypertension but could also reverse established pulmonary vascular remodeling. Rosiglitazone also attenuated hypoxia-induced increases in right ventricular hypertrophy, proliferating cellular nuclear antigen staining, lung collagen and elastin content, small molecular weight forms of matrix metalloproteinase II, and c-Kit+ cells. This report provides provocative evidence that activation of the PPARγ receptor with TZDs has potential to favorably modulate a variety of pathways involved in hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling.

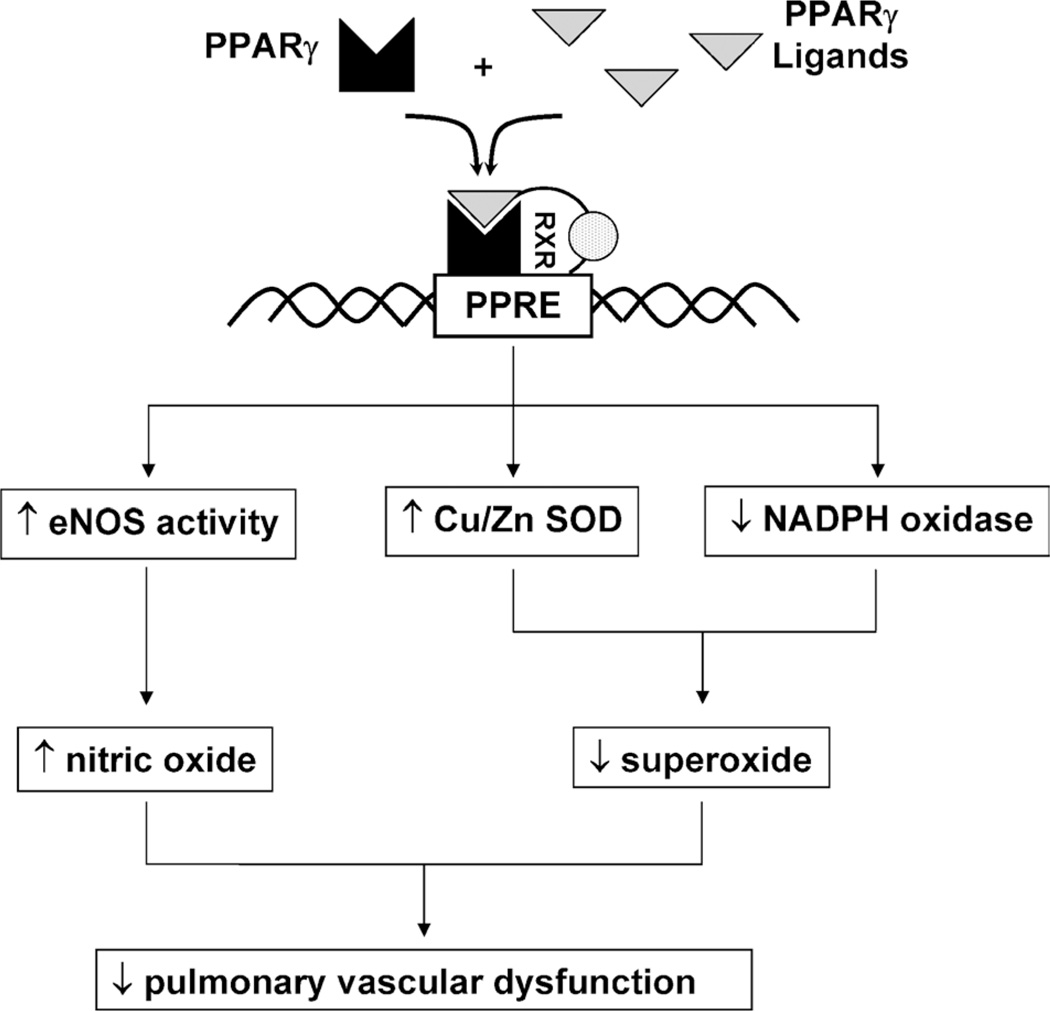

We recently reported similar preliminary data in a mouse model of pulmonary hypertension.18 C57Bl/6 mice that were exposed to 10% oxygen for 3 weeks developed significant pulmonary hypertension manifested as increases in right ventricular systolic pressure and right ventricular hypertrophy. Treatment with rosiglitazone for the last 10 days of this hypoxia regimen (10 mg/kg per day by gavage) significantly attenuated hypoxia-induced increases in right ventricular systolic pressure and right ventricular hypertrophy. We speculated that these effects were related to alterations in the production of vasoactive reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (Fig. 1). For example, our previous work demonstrated that PPARγ ligands enhanced endothelial nitric oxide production19,20 through posttranslational mechanisms that increased nitric oxide synthase activity rather than its expression. Evidence that these effects were mediated through PPARγ were provided by studies demonstrating that ligand effects were abrogated by treatment with either pharmacological PPARγ antagonists or small interfering RNA to PPARγ.21 Furthermore, PPARγ ligands inhibited endothelial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase expression, activity, and superoxide production.22,23 These findings suggest that PPARγ ligands could restore redox balance in the pulmonary circulation to improve endothelial dysfunction, a critical derangement leading to pulmonary vasoconstriction and vascular remodeling. In support of this concept, we recently demonstrated that vascular NADPH oxidase expression is significantly increased in leptin receptor–deficient animals and that treatment with rosiglitazone (3 mg/kg per day for 1 week) significantly attenuated vascular NADPH oxidase expression and superoxide production.23 These findings provide important new evidence that vascular NADPH oxidase is a target of PPARγ ligands and contribute additional insights into mechanisms underlying the vascular protective effects of PPARγ ligands.

FIGURE 1.

Potential mechanisms of PPARγ-mediated alterations in the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species that modulate pulmonary vascular function and the development of pulmonary hypertension. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ ligands bind to the PPARγ receptor that forms a heterodimer with the RXR. This activated heterodimer recruits coactivator molecules to the transcriptional start site of genes that contain PPAR response elements. In vascular endothelial cells, PPARγ ligands stimulate nitric oxide production through PPARγ-dependent pathways that activate endothelial nitric oxide synthase through posttranslational mechanisms.20 Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ ligands also coordinately regulate endothelial superoxide production by simultaneously increasing the expression and activity of the superoxide-degrading enzyme, Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase, and by decreasing the expression of selected subunits of the superoxide-producing NADPH oxidase.22,23 We postulate that the collective effect of enhanced nitric oxide production and reduced superoxide production leads to reduced endothelial dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension. eNOS indicates endothelial nitric oxide synthase; PPRE, PPAR response element; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ ligands have been shown to attenuate pulmonary hypertension in yet another experimental model. Hansmann et al24 recently reported that male ApoE–deficient mice fed high-fat diets for 15 weeks developed significant increases in right ventricular systolic pressure, pulmonary vascular remodeling, and right ventricular hypertrophy. These animals also developed insulin resistance and reductions in serum levels of the adipocytokine, adiponectin. Treatment with rosiglitazone (10 mg/kg per day incorporated into the diet) increased adiponectin levels, attenuated insulin resistance, and reversed indices of pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling. Based on in vitro evidence that recombinant ApoE and adiponectin attenuate platelet-derived growth factor BB–mediated proliferation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells, these results not only provided novel evidence for potential roles of metabolic derangements in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension but further underscored the capacity of PPARγ ligands to modulate pathways involved in pulmonary hypertension pathogenesis.

Collectively, the studies reviewed in this report illustrate that reductions in pulmonary vascular PPARγ expression are associated with pulmonary hypertension and that TZD ligands that activate PPARγ have the capacity to reduce pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling in several experimental models. Studies elucidating the mechanisms of PPARγ ligand effects in the pulmonary vasculature point to PPARγ-mediated alterations in vascular cell proliferation and signaling, progenitor cell function, and the production of vasoactive reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Additional studies determining the precise gene and signaling targets of PPARγ will be required to further clarify the therapeutic potential of PPARγ ligands in pulmonary vascular disease. Given the current availability of PPARγ ligands in our pharmacological armamentarium and the urgent need for new therapies in pulmonary hypertension, progress in translational studies may inform clinical trials in the near future that investigate the use of PPARγ ligands in the management of pulmonary hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Veterans Affairs Research Service, the National Institutes of Health, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

The proceedings of a symposium presented at the Experimental Biology Meeting in Washington, DC, on Sunday, April 29, 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Issemann I, Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature. 1990;347(6294):645–650. doi: 10.1038/347645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gearing KL, Gottlicher M, Teboul M, et al. Interaction of the peroxisome-proliferator–activated receptor and retinoid X receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(4):1440–1444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yki-Jarvinen H. Thiazolidinediones. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(11):1106–1118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyduk A, Croft JB, Ayala C, et al. Pulmonary hypertension surveillance—United States, 1980–2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2005;54(5):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li AC, Brown KK, Silvestre MJ, et al. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma ligands inhibit development of atherosclerosis in LDL receptor–deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(4):523–531. doi: 10.1172/JCI10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z, Ishibashi S, Perrey S, et al. Troglitazone inhibits atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E–knockout mice: pleiotropic effects on CD36 expression and HDL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21(3):372–377. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins AR, Meehan WP, Kintscher U, et al. Troglitazone inhibits formation of early atherosclerotic lesions in diabetic and nondiabetic low density lipoprotein receptor–deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21(3):365–371. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cominacini L, Garbin U, Fratta Pasini A, et al. Troglitazone reduces LDL oxidation and lowers plasma E-selectin concentration in NIDDM patients. Diabetes. 1998;47(1):130–133. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murakami T, Mizuno S, Ohsato K, et al. Effects of troglitazone on frequency of coronary vasospastic-induced angina pectoris in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(1):92–94. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00199-x. 1A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minamikawa J, Tanaka S, Yamauchi M, et al. Potent inhibitory effect of troglitazone on carotid arterial wall thickness in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(5):1818–1820. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takagi T, Akasaka T, Yamamuro A, et al. Troglitazone reduces neointimal tissue proliferation after coronary stent implantation in patients with non–insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: a serial intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(5):1529–1535. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00895-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidhu JS, Kaposzta Z, Markus HS, et al. Effect of rosiglitazone on common carotid intima-media thickness progression in coronary artery disease patients without diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(5):930–934. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000124890.40436.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campia U, Matuskey LA, Panza JA. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor–gamma activation with pioglitazone improves endothelium-dependent dilation in nondiabetic patients with major cardiovascular risk factors. Circulation. 2006;113(6):867–875. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.549618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ameshima S, Golpon H, Cool CD, et al. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) expression is decreased in pulmonary hypertension and affects endothelial cell growth. Circ Res. 2003;92(10):1162–1169. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000073585.50092.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda Y, Hoshikawa Y, Ameshima S, et al. Effects of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma ligands on monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2005;43(5):283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lame MW, Jones AD, Wilson DW, et al. Protein targets of monocrotaline pyrrole in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(37):29091–29099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crossno JT, Jr, Garat CV, Reusch JE, et al. Rosiglitazone attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292(4):L885–L897. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00258.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nisbet R, Kleinhenz D, Thorson H, et al. Rosiglitazone attenuates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:A43. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0132OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calnek DS, Mazzella L, Roser S, et al. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma ligands increase release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(1):52–57. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000044461.01844.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polikandriotis JA, Mazzella LJ, Rupnow HL, et al. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma ligands stimulate endothelial nitric oxide production through distinct peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma–dependent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(9):1810–1816. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000177805.65864.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polikandriotis JA, Rupnow HL, Hart CM. Chronic ethanol exposure stimulates endothelial cell nitric oxide production through PI-3 kinase– and hsp90-dependent mechanisms. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(11):1932–1938. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000187597.62590.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang J, Kleinhenz DJ, Lassegue B, et al. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor–gamma ligands regulate endothelial membrane superoxide production. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288(4):C899–C905. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00474.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang J, Kleinhenz DJ, Rupnow HL, et al. The PPARgamma ligand, rosiglitazone, reduces vascular oxidative stress and NADPH oxidase expression in diabetic mice. Vascul Pharmacol. 2007;46(6):456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansmann G, Wagner RA, Schellong S, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension is linked to insulin resistance and reversed by peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor–gamma activation. Circulation. 2007;115(10):1275–1284. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.663120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]