Abstract

Estrogen Receptor (ER) α activity is controlled by the balance of coactivators and corepressors contained within cells which are recruited into transcriptional complexes. The metastasis associated (MTA) family of proteins have been demonstrated to be associated with breast tumor cell progression and ERα activity. We show that the MTA2 family member can bind to ERα and repress its activity in human breast cancer cells. Furthermore, it can inhibit ERα mediated colony formation and render breast cancer cells resistant to estradiol and the growth-inhibitory effects of the antiestrogen tamoxifen. MTA2 participates in the deacetylation of ERα protein, potentially through its associated HDAC1 activity. We hypothesize that MTA2 is a repressor of ERα activity and that it could represent a new therapeutic target of ERα action in human breast tumors.

Keywords: Estrogen receptor alpha, Breast Cancer, Endocrine Therapy, Protein Acetylation, Repressor

INTRODUCTION

Nuclear receptors represent a superfamily of ligand-dependent transcription factors which provide diverse functions in regulating cell growth, differentiation, development, as well as homeostasis upon ligand binding (1-4). Like other family members, estrogen receptor α (ERα) displays a modular structure with four well-conserved domains: a DNA binding domain (DBD), an amino-terminal Activation Function (AF)-1 domain harboring an autonomous activation function, and a carboxy-terminal AF-2 domain which contains a dimerization interface as well as a ligand binding structure. ERα also contains a hinge region connecting the DNA and hormone binding domains (HBD) that encodes a nuclear localization signal (5), but whose overall function is less well characterized. In addition to being activated by hormone binding, ERα activity is also regulated by coactivator/corepressor coregulatory protein complexes [reviewed in (4)], diverse growth factor signals (6), and mutation (7).

In the absence of hormone or in the presence of antiestrogen, it is thought that ERα activity is maintained in an inactive state by its recruitment and binding to constitutively associated corepressor histone deacetylase complexes (HDACs); upon exposure to estrogen, these corepressor complexes are released with subsequent transient association of receptor-associated coactivator proteins (8). While corepressor complexes containing nuclear receptor corepressor (N-CoR) and silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid receptors (SMRT) possess histone deactylase activity, the majority of identified ERα coactivators, such as p300/CBP, SRC1, and SRC3 encode intrinsic histone acetyl transferase (HAT) activity (9, 10). The steady state level of acetylation at estrogen-responsive promoters is dictated by the balance of HDACs and HATs recruited to these sites. In addition to acetylating the core histones residing at gene promoters and hence modifying chromatin structure, p300 can also directly acetylate ERα and modulate ERα activity (11). Furthermore, p300-mediated acetylation of the SRC3/ACTR coactivator disrupts promoter-bound ERα which coincides with the attenuation of hormone-induced transcriptional activity (12). Therefore, it has been hypothesized that the processes of protein acetylation and deacetylation may play important roles in ERα activation and/or repression, and that disruption of ERα protein acetylation could result in altered function (11).

We have previously reported a lysine to arginine somatic mutation in the hinge domain of ERα (called K303R ERα) in human premalignant breast lesions, which exhibited altered growth response to hormone (7). Independently this residue was identified as a component of a conserved acetylation motif that serves as a substrate for acetylation by p300 (11). Since we also found that, compared with wild-type ERα, the K303R ERα mutant showed enhanced association with the SRC2 coactivator in response to hormone (7), we questioned whether the mutation might similarly be differentially regulated by receptor corepressors.

Metastasis-associated protein 2 (MTA2), also known as MTA1-Like 1 and PID (p53 target protein in the deacetylase complex) belongs to a highly conserved family of proteins originally identified by differential cDNA screening of rat adenocarcinoma cell lines with low and high metastatic potential (13). MTA2, as well as the prototype family member MTA1 (14), is contained in nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylation (NuRD) complexes that are involved in both nucleosome remodeling and which possess histone deacetylase activity (15). MTA2 expression enhances p53 deacetylation through targeting of p53 to HDACs, thereby strongly repressing p53-dependent transcriptional activation (16). In addition, MTA1 is an ERα corepressor protein, and its overexpression can inhibit ERα transcriptional activity (17). We therefore examined whether MTA2 might also function as an ERα corepressor protein, and modulate ERα activity through its associated HDAC activity.

Herein we demonstrate that MTA2 binds to ERα and inhibits the transcriptional activity of wild-type ERα, functioning as a receptor repressor. However MTA2 overexpression was unable to similarly inhibit the transcriptional activity of the K303R ERα mutant. We found that MTA2-containing HDAC1 complexes can deacetylate p300-acetylated ERα. Taken together, our results suggest that MTA2 is a component of the NuRD complex which serves to modulate the post-translational acetylation status and activity of ERα.

RESULTS

MTA2 inhibits ERα transcriptional activity and colony formation of ERα-positive human breast cancer cells

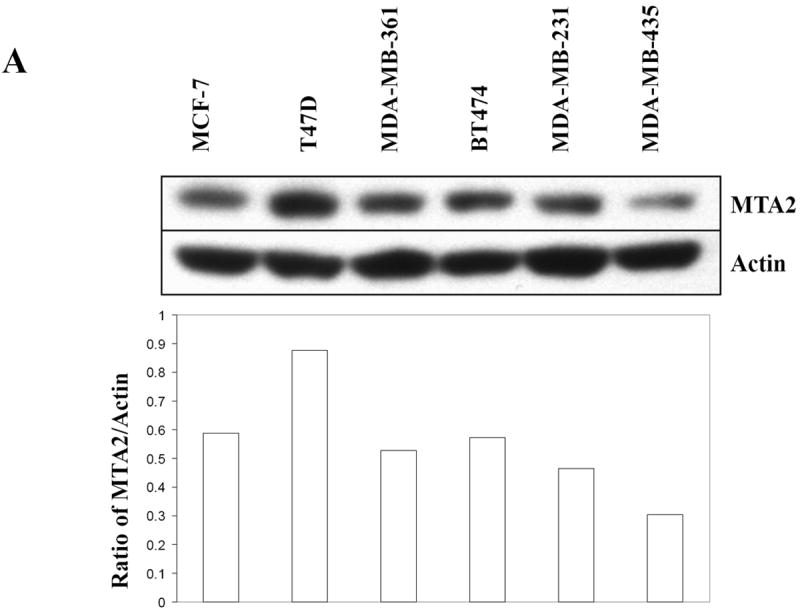

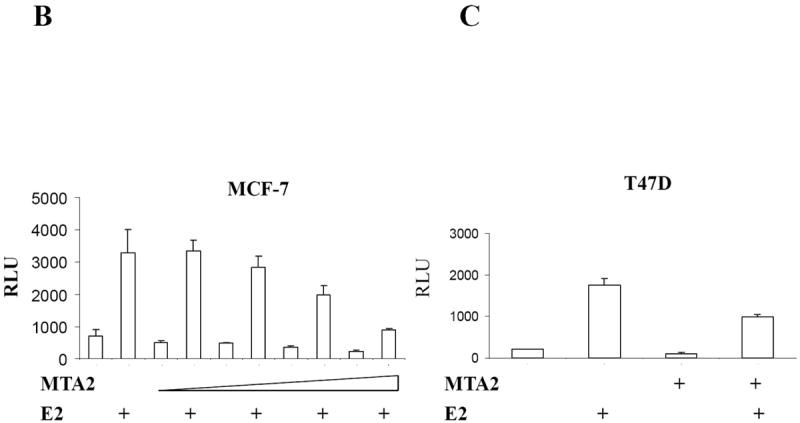

It has been previously reported that MTA1 expression represses ERα transcriptional activity (17) and that MTA3 transcription is hormonally regulated in breast cancer cells (18). The levels of all three family members appear to be expressed ubiquitously. To examine the levels of MTA2 in different human breast cancer cells, we performed immunoblot analysis for endogenous MTA2 and quantitated levels relative to actin, Figs. 1A upper and lower panels, respectively. The levels of MTA were equivalent in the ER-positive MCF-7, MDA-MB-361, and BT474 cells. The highest protein levels were seen in the ERα-positive T47D cell line, but lower levels were expressed in the two ER-negative cell lines, MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-435.

Fig.1.

MTA2 inhibits ERα transcriptional activity and colony formation in human breast cancer cells.

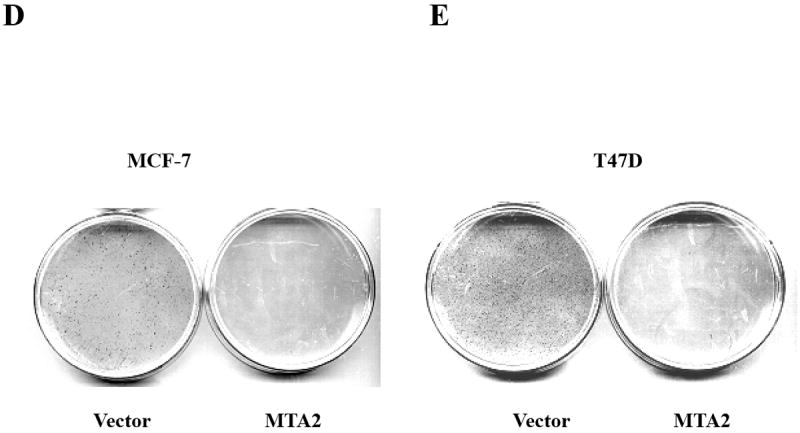

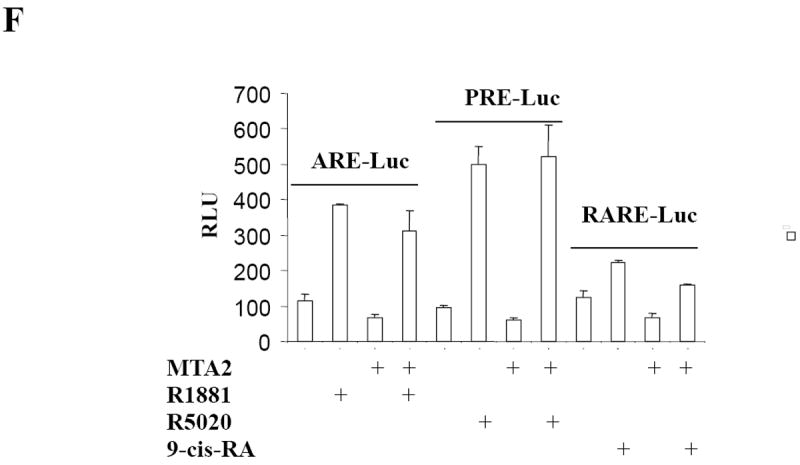

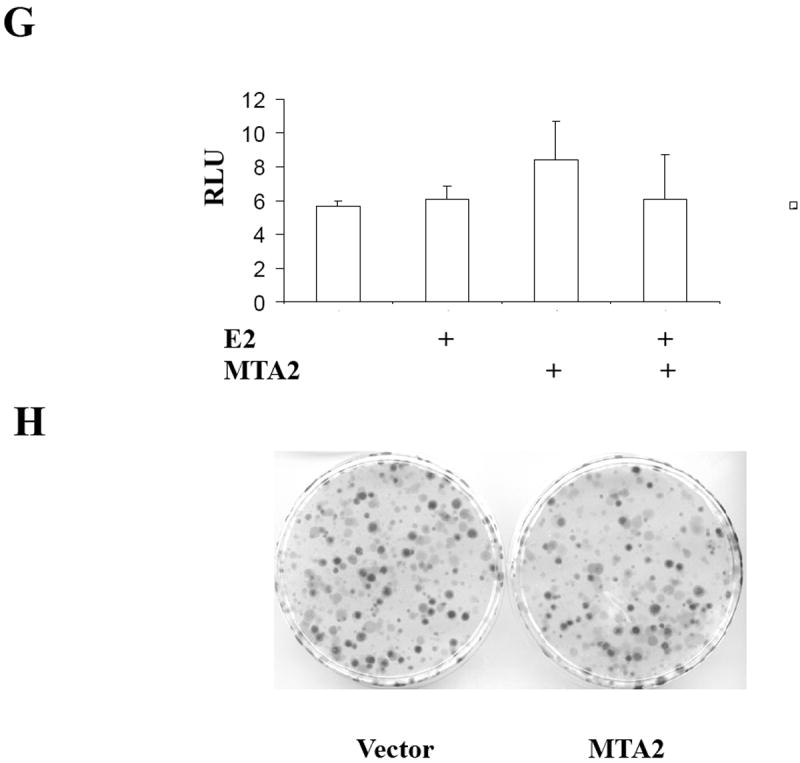

(Panel A) Immunoblot analysis of different breast cancer cell lines with antibodies to MTA2, β-actin (upper panel), the lower panel is the relative level of MTA2 normalized to the respective β-actin level in each cell line, and is a representative of three independent experiments. Transfection of 1 μg ERE2-tk-Luc with increasing amounts of of expression vector plasmids of either MTA2 (0.2, 0.4, 0.6 0.8 μg) or empty vector into MCF-7 (panel B), or 0.8 μg of expression plasmid of MTA2 or empty vector into T47D (panel C), or MDA-MB-231 (panel G) cells, treated with 10-9 M estradiol (E2) for 18-24 hours. (Panel F.) Transfection of 1 μg ARE-Luc, PRE-Luc or RARE-Luc with 0.8 μg of expression vector plasmids of either MTA2 or empty vector into MCF-7 cells, treated with 10-9 M R1881, R5020 or 9-cis-RA respectively for 18-24 hours. Luciferase activites were normalized to the cotransfected pCMV-β-gal vector. The data shown represents the mean ± SEM for 3 independent experiments. Panels D, E, and H represent the colony formation assays of either MTA2 expression plasmid or control vectors transfected into MCF-7 (Panel D), T47D (Panel E), or MDA-MB-231 (Panel G) cells.

To test for an effect of MTA2 overexpression on ERα activity, we transiently transfected a MTA2 expression vector into the MCF-7 and T47D cell lines. Transcriptional activity of endogenous ERα was then measured using a cotransfected estrogen-responsive luciferase reporter gene (Fig 1B and C). After exposure to 1 nM E2, ERα activity was increased approximately 10-15 fold in the two cell lines. Cotransfection of MTA2 significantly blocked the ability of estrogen to stimulate ERα transcription. Increasing levels of MTA2 in MCF-7 cells reduced estrogen-induced activity by approximately 75%. Levels of ERα activity in T47D cells were also reduced. MTA2 overexpression only minimally affected estrogen-independent basal activity in these cells. MTA2 expression had no effect on ERα activity in the presence of the antiestrogen tamoxifen (data not shown). These data demonstrate that MTA2 overexpression can repress estrogen-induced ERα transcriptional activity in ERα-positive breast cancer cells.

ERα activity is essential for the growth and survival of normal breast epithelium and hormone-dependent breast tumor cells. Since MTA2 inhibits endogenous ERα transcriptional activity in two hormone-dependent breast cancer cells, we next examined the effect of MTA2 expression on colony formation (Fig. 1D and E). This assay has previously been used to test the effect of another ERα repressor, the BRCA1 tumor suppressor gene (19). Either MTA2 expression vector or the control vector were transfected into MCF-7 and T47D cells, and the ability to form colonies was assessed after 14 days of selection with G418 antibiotic. Overexpression of MTA2 noticeably inhibited the colony formation was by 96.05% ±0.56% and 94.03 % ± 0.42%, compared to the vector control groups in MCF-7 and T47D cells, respectively.

To test whether MTA’s effects were associated with ERα-expression, we performed transient transactivation assays using a number of nuclear receptor luciferase reporters in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 1F), as well as transient transactivation (Fig. 1G), and colony formation (Fig. 1H) assays in the estrogen-independent MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line. Although MTA2 exhibits strong transcriptional repression activity on promoters containing Gal4-binding sites when it is fused to a Gal4 DNA binding domain (20), two of the other nuclear receptors tested—the androgen receptor with the ARE-Luc, progesterone receptor with the PRE-Luc—were modulated by MTA2 overexpression in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 1F). There was a marginal decrease in activity of the retinoic acid receptor with the RARE-Luc reporter when MTA2 was overexpressed (Fig. 1F). In addition, neither estrogen-induced ERα transcriptional activity nor colony formation was influenced by overexpression of MTA2 in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figs. 1G and H). Therefore, MTA2’s effects on estrogen-induced activity and growth may be related to the expression of ERα.

MTA2 binds to ERα, and mapping of their interaction sites

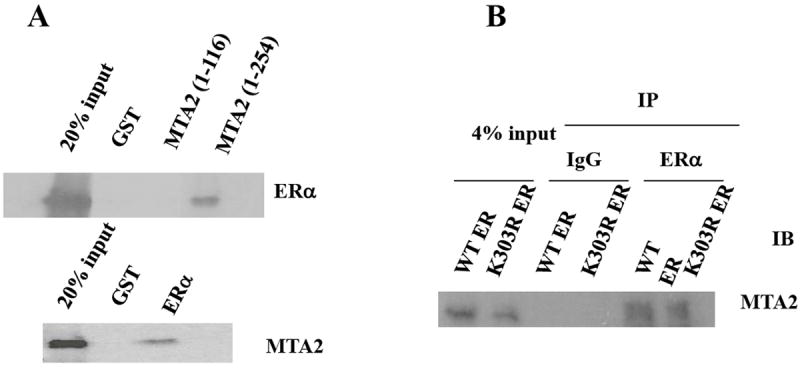

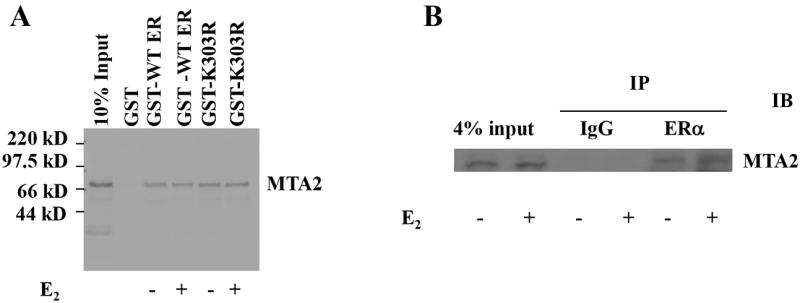

The SMRT and N-CoR ERα transcriptional repressors bind directly to nuclear receptors (21, 22), as do several of the components of the NuRD complex, for example HDAC1 (23, 24). To determine whether MTA2 can bind ERα, we performed in vitro GST-pulldown binding experiments which gives a qualtitative assessment of binding (Fig. 2). Incubation of in vitro translated ERα with two GST-MTA2 fragments bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads (Fig. 2A, top panel), or full-length MTA2 with GST-ERα (Fig. 2A, lower panel) demonstrated an interaction between the two proteins. All incubations were performed in the absence of estrogen. There was no binding when ERα or MTA2 was bound to GST only, and the interaction between the proteins appeared to be mediated by the amino-terminal MTA2 region containing residues 116 to 254.

Fig. 2.

MTA2 is an ERα-binding protein.

(Panel A). In vitro interaction: ERα and MTA2 were labeled with 35S-methionine by in vitro translation and tested for interaction with GST-MTA2 and GST-ERα respectively in the absence of ligand. (Panel B). In vivo interaction: HeLa cells were transiently transfected with Flag-MTA2 and expression vectors for either HA-tagged wild type (WT) or K303R mutant (K303R) ERα. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with either anti-HA monoclonal antibody-conjugated sepharose (ERα) or protein G sepharose (IgG) as a negative control. The immunoprecipitates were then subjected to immunoblot analysis (IB) with an anti-M2 antibody.

We next examined whether the interaction between MTA2 and ERα could occur in cells. Therefore, we transiently transfected HeLa cells with Flag-tagged MTA2, and either wild-type (WT) or the K303R mutant ERα (Fig. 2B). Immunoprecipitation (IP) of ERα followed by immunoblotting (IB) for MTA2 with an antibody to the Flag peptide tag revealed a band with the molecular mass of MTA2; MTA bound to both WT and the K303R ERα mutant. MTA2 was not present in IgG control precipitated complexes. Thus, MTA2 is an ERα binding protein.

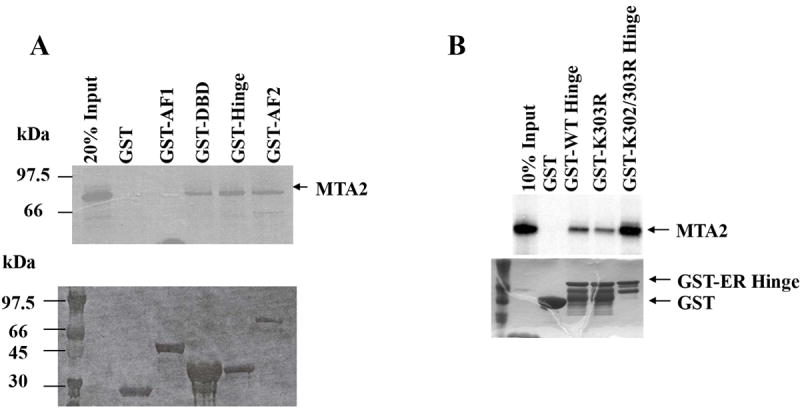

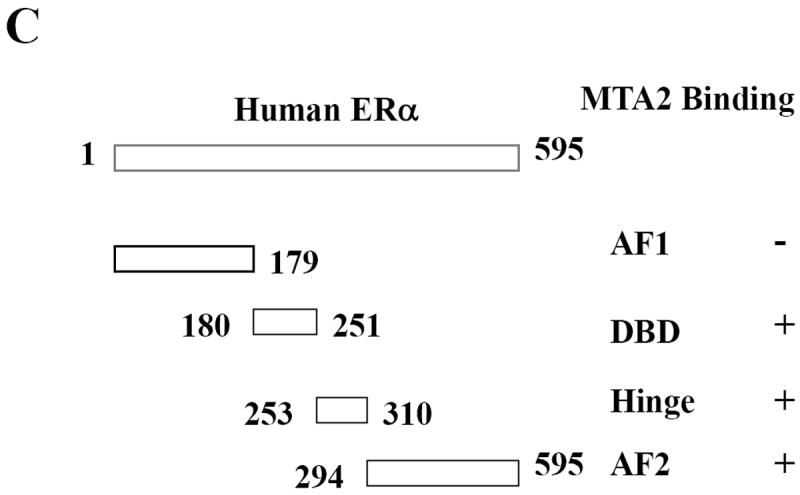

ERα contains at least four functional domains, and the ability of MTA2 to interact with these different domains (represented graphically in Fig. 3C) was examined using GST-pulldown assays. The different GST-ERα fusion proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue, to ensure that the input of immobilized GST-fragments was equal (data not shown). We examined MTA2 interactions with GST alone, ERα AF1, DBD, hinge, and AF2 domains (Fig. 3A). All incubations were done in the absence of hormone. We found that MTA2 interacted with all of the ERα domains except the amino-terminal AF1 region. Thus as described for a number of repressors, MTA2 interacts with multiple regions of ERα. Figure 2B, upper panel, examines the binding of MTA2 to the isolated hinge domain of ERα using the acetylation mutants of this region; the input is shown in the lower panel. Binding of WT and the single K303R ERα mutant were equivalent; however increased binding was seen with the double mutant K302/K303R. This suggests that although the acetylation potential of the ERα hinge domain is not necessary for this interaction, these two acetylation sites can affect this interaction.

Fig. 3.

Mapping of the interaction sites between ERα and MTA2.

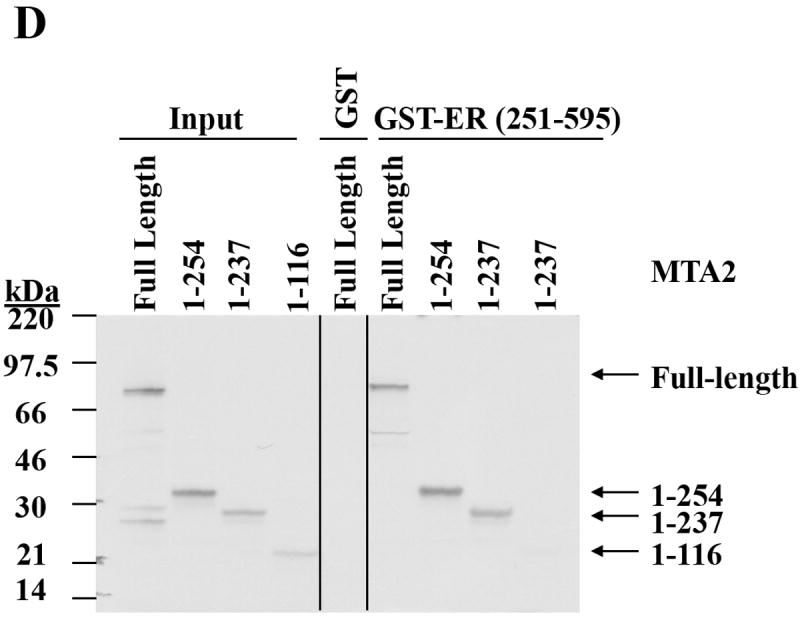

(Panel A). To map ERα binding sites in MTA2, different GST-fusion fragments of ERα were incubated with in vitro translated full-length MTA2 in the absence of ligand (upper panel; the Commassie blue staining of this gel is shown in the lower panel). (Panel B). GST-ERα hinge fragments were incubated with MTA2 (upper panel; the Commassie blue staining of this gel is shown in the lower panel). (Panel C). Schemata of MTA2 binding to ERα regions. (Panel D). Mapping of MTA2 binding sites in ERα: full-length and different fragments of MTA2 were labeled with 35S–methionine using in vitro translation and tested for interaction with equal amounts of GST-ERα hinge-AF2 domain regions in the absence of ligand. (Panel E). Schemata showing MTA2 structural domains and summarization of its binding to ERα.

MTA2 also encodes several functional domains (25), which are schematically represented in Fig. 3E. The results in Fig 2A suggested that either the MTA2 leucine zipper motif (residues 234 to 254), the bromo-adjacent domain (BAH domain, residues 4-144), or the intervening region (ELM 2 domain, residues 145-206) between these two domains could interact with ERα. Therefore we used a GST-ERα hinge/AF2 fusion fragment (residues 251-595) immobilized on glutathione beads and incubated this with deletion fragments of MTA2 (Fig. 3D, and summarized in 3E). The fragment containing the MTA2 BAH and ELM2 domains interacted with ERα, but the leucine zipper motif did not appear to be essential for this interaction since its removal did not negate binding.

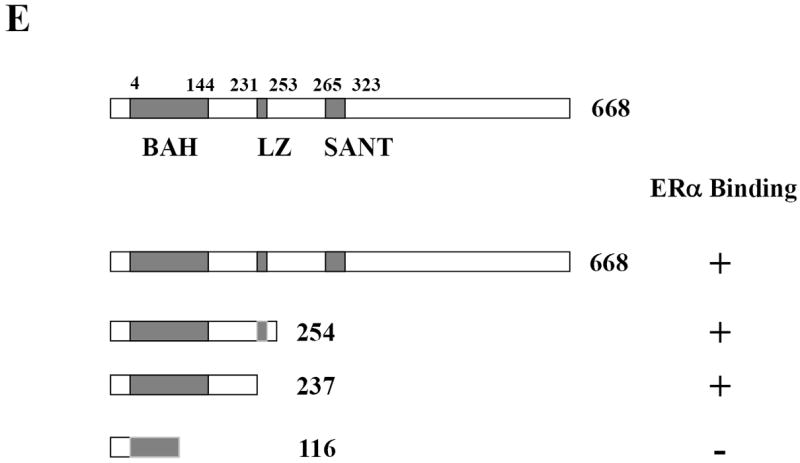

The AF2 domain contains a conserved amphipathic α-helix structure in helix 12, which is essential for hormone-inducible function. Upon hormone binding, this helix folds back and generates a transcriptionally-active conformation (26). We next investigated whether hormone would affect ERα AF2 domain—MTA2 interactions. We performed GST-pulldown as well as coimmunoprecipitation experiments to address this question; the results shown in Figs. 4A and B demonstrate that the binding is constitutive and estrogen treatment does not interfere with their interaction either in vitro or in cells. Figure 4A also demonstrates that regardless of bound hormone the K303R ERα mutation does not alter this interaction.

Fig. 4.

Hormone binding does not alter the interaction between ERα and MTA2 in the nucleus.

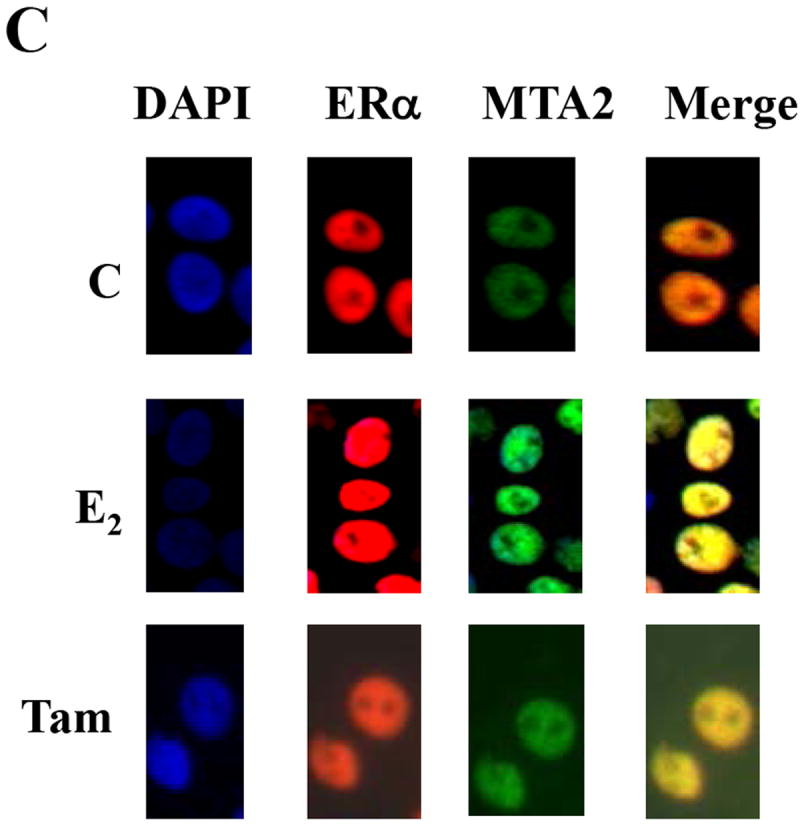

(Panel A). Full length MTA2 was labeled with 35S–methionine using in vitro translation and interacted with equal amounts of either GST-WT ERα or GST-K303R ERα in the absence or presence of 1 nM E2. (Panel B). HeLa cells were transiently transfected with an expression vector for HA-tagged wild type (WT) with Flag-tagged MTA2 and 24 hours later the cells were treated by 1 nM E2 for another 24 hours. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with either anti-HA monoclonal antibody conjugated sepharose or protein G sepharose (IgG, negative control) in the absence or presence of 1 nM E2. The immunoprecipitates were then subjected to electrophoresis, and staining with an anti-M2 antibody to detect MTA2. (Panel C) T47D cells were treated with 100 nM E2 or OHT for 2 hours, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and processed for indirect immunofluorescence with an anti-ERα antibody (green) and an anti-MTA2 antibody (red). DAPI (blue) co-staining was used to visualize the nuclei. The merged images are shown in the panels on the right.

It is known that transcriptional regulation takes place in the nucleus, and that MTA2 protein is located in the nucleus in a distinct complex from the MTA1 protein (20). The subcellular localization of endogenous ERα and MTA2 in T47D cells was analyzed using indirect fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4C). Nuclei are revealed by DAPI staining in the control-treated (C), or E2 and Tam-treated cells. Both ERα (red) and MTA2 (green), and the merged fluorescent images were clearly localized to the nucleus under all treatment conditions.

MTA2 is an inadequate repressor of the K303R ERα mutant

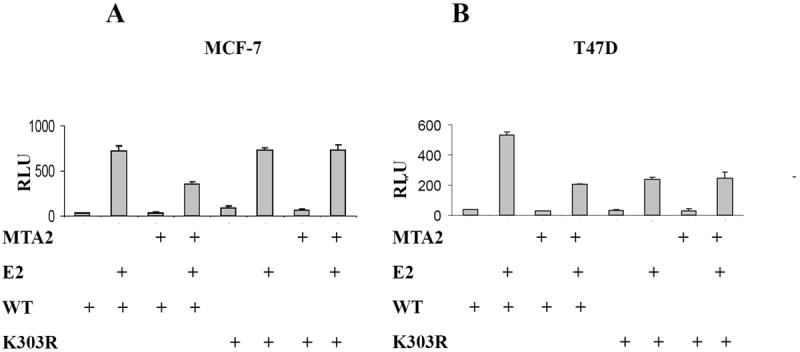

MTA2 is a component of the core NuRD complex (27) and inhibits the transcriptional activity of wild-type, but not a p53 mutant harboring mutations in potential acetylation sites (16). This raises the possibility that MTA2 may only act on acetylated or acetylation-competent p53 protein in addition to its effects on chromatin. We have previously reported that the K303R mutation disrupts the major acetylation site of ERα, generating a hypoacetylated form of the receptor (11). To address whether this mutation would compromise MTA2’s effects on ERα, we performed transient transactivation assays (Fig. 5). MTA2 expression vectors were cotransfected with either wild-type (WT) or the K303R ERα mutant DNA into both MCF-7 and T47D breast cancer cells. As we observed with endogenous ERα levels, overexpression of MTA2 repressed wild-type ERα activity by 42% and 46% in MCF-7 and T47D cells (Fig. 5A and B, respectively). However, MTA2 expression had no effect on the K303R ERα mutant transcriptional activity, showing that the mutation impairs MTA2-mediated repression. A similar lack of repression was seen with two other ERα corepressors, BRCA-1 and N-CoR (results not shown). Similar levels of MTA2 and ERα protein were expressed in these transient transfections as demonstrated by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5C). This result suggested that the acetylation potential of the receptor is important for MTA2’s repressor effect on its transcriptional activity in breast cancer cells.

Fig. 5.

MTA2 is an insufficient repressor of the K303R ERα mutant.

Cotransfection of ERE-tk-Luc, and either WT or K303R ERα vectors with expression vectors MTA2 or empty vector into MCF-7 (Panel A) or T47D (Panel B) cells treated with 1 nM E2 for 18-24 hours. Luciferase values were normalized to a cotransfected pCMV-β-gal control vector (RLU). An immunoblot analysis of MCF-7 cells transfected with the ERα and MTA2 vectors is shown in Panel C to demonstrate that the exogenous proteins were similarly expressed. The transactivation data shown represents the mean ± SEM for 3 separate transfections.

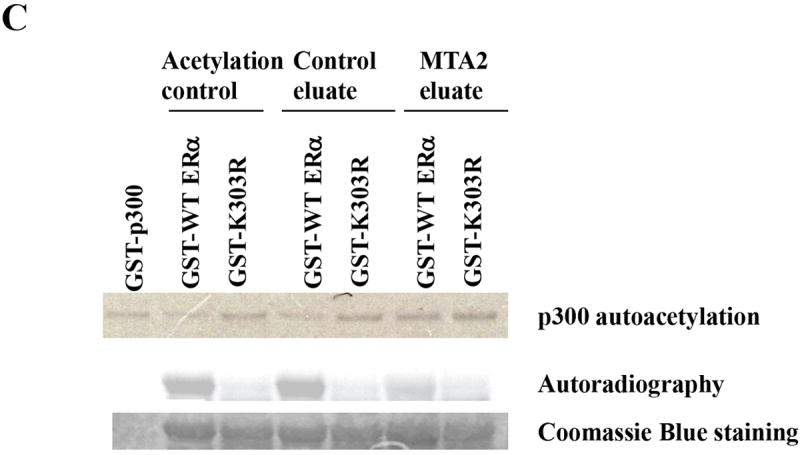

MTA2-associated HDAC1 deacetylase activity mediates ERα deacetylation

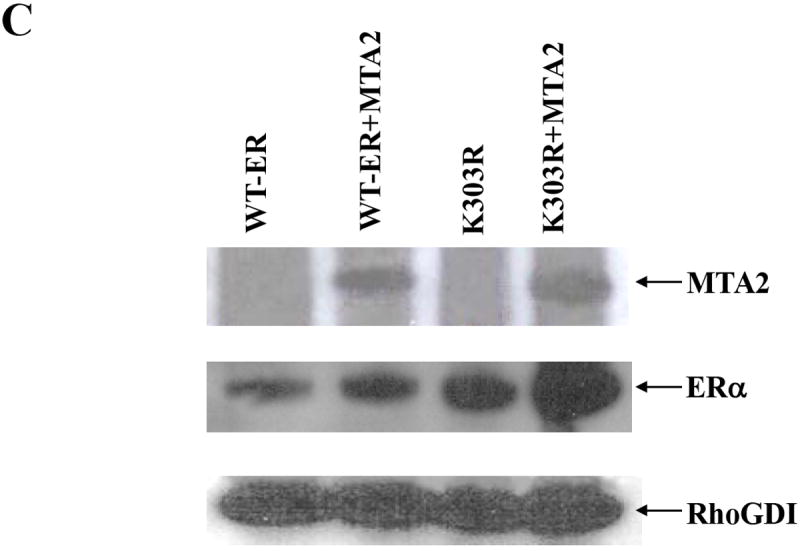

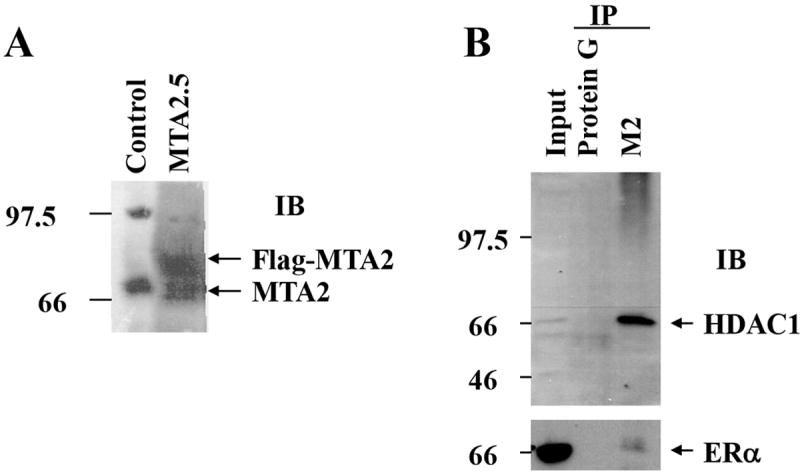

Experiments were next performed to investigate whether MTA2 participates in ERα deacetylation. We first established a T47D cell line overexpressing Flag-MTA2 (Fig. 6, Panel A), to obtain purified MTA2-associated deacetylase complexes for functional analysis on ERα protein. High salt cell extracts from these cells were then subjected to affinity chromatography on M2-sepharose and the Flag-MTA2 deacetylase complexes eluted with Flag peptide. This technique has been previously utilized to demonstrate MTA2’s effect on p53 acetylation (16). Western blot analysis indicated that both HDAC1 and ERα were contained in the MTA2-purified complex (Fig. 6B, IP M2), but not in the control, Protein G-IP complex. This demonstrates that both HDAC1 and ERα are specifically associated with overexpressed MTA2 protein in these cells.

Fig. 6.

MTA2-associated complexes participate in the deacetylation of ERα.

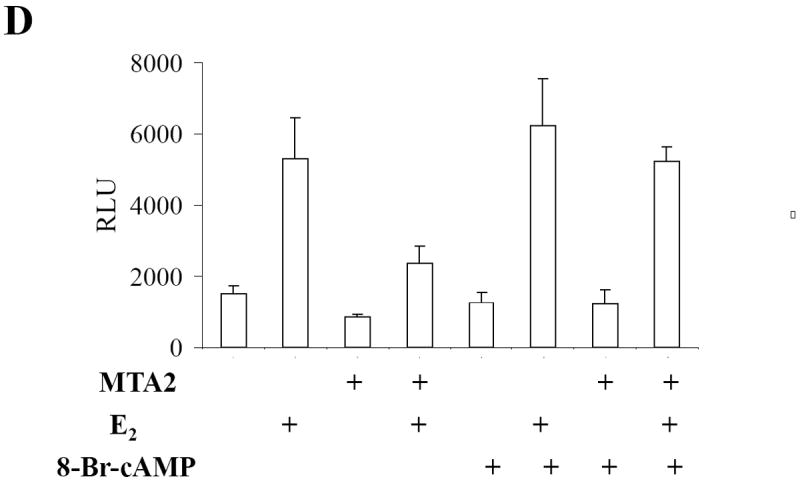

(Panel A) Construction of T47D cells overexpressing MTA2: Flag-tagged MTA2 or control vector were stably transfected and overexpressed in T47D cells. Cell lysates from a vector control and MTA2.5 clone were resolved by electrophoresis, and an anti-PID polyclonal antibody was used to detect the expression of Flag-MTA2. Endogenous MTA2 is shown below the exogenous Flag-MTA2, and is denoted with arrows. (Panel B). Cell lysates from T47D cells overexpressing MTA2 were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with either protein G sepharose as a negative control, or anti-M2 sepharose. The immunoprecipitates were eluted with Flag peptide and resolved by electrophoresis. Anti-HDAC1 antibody was used to detect the presence of HDAC1. The same immunoblot membrane was then stripped and the presence of ERα was detected with a specific anti-ERα antibody. (Panel C). Purified GST-WT or K303R ERα hinge fragments were acetylated by purified p300 HAT protein, and then deacetylated using the control and MTA2 elutates. The reactions were resolved by electrophoresis and analyzed by both Coomassie Blue staining and autoradiography. (Panel D) Transfection of 1 μg ERE2-tk-Luc with 0.8 μg of expression vector plasmids of either MTA2 or empty vector into MCF-7 cells. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were treated with 10-9 M estradiol (E2) and/or 100 nM 8-Br-cAMP for 18-24 hours. Luciferase activity was normalized to the cotransfected β-galactosidase activity. The data shown represents the mean ± SEM for 3 independent experiments.

These complexes were then tested for deactylation activity on ERα previously acetylated in vitro by p300 HAT (Fig. 6C). As expected wild-type (WT) ERα is efficiently acetylated by GST-p300; the K303R ERα mutant was deficient in acetylation (Acetylation control). Incubation of WT or the K303R ERα with the control eluate had no effect on the acetylation status of the receptors. However, WT ERα was deacetylated by the purified MTA2-associated complex (MTA2 eluate), suggesting that the MTA2 complex can indeed deacetylate ERα, probably through its associated HDAC1 deacetylase activity.

We have recently demonstrated that activation of protein kinase A (PKA) signaling by the cell-permeable cyclic AMP analogue 8-bromo-cAMP leads to phosphorylation of ERα at serine 305 which blocks protein acetylation at lysine 303 (28). We therefore utilized 8-Br-cAMP treatment and examined the transcription effect of MTA2 on ERα transcriptional activity in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 6D). As expected MTA2 overexpression inhibited estrogen-induced ERα transcriptional activity in these cells. Blocking ERα acetylation at the K303 residue using 8-Br-cAMP treatment blocked MTA2 repression of ERα activity. We thus hypothesize that MTA2’s repressor effect on WT ERα transcriptional activity may be due to its ability to modulate ERα deacetylation, and that the K303R ERα mutant was refractory to this inhibition because of its hypoacetylated status. These results suggest that MTA2 may function as an ERα transcriptional repressor via its effects on acetylation.

MTA2 overexpression renders breast cancer cells unresponsive to hormone

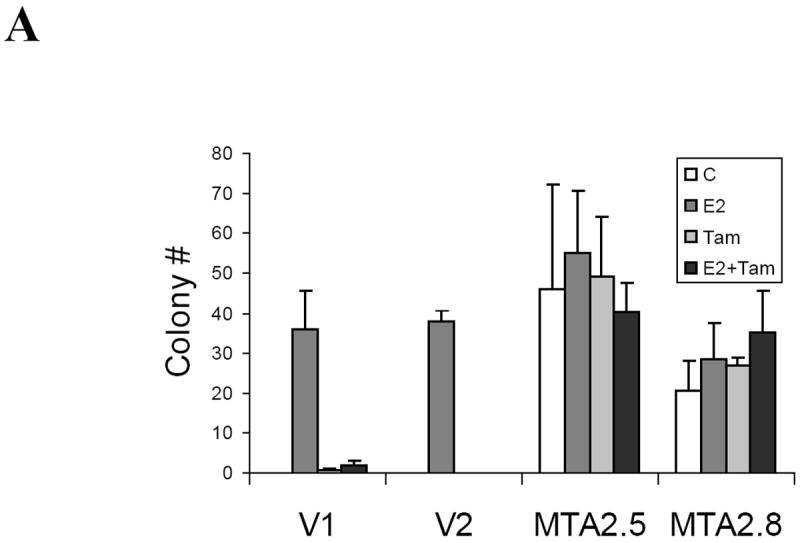

Expression of both MTA1 and MTA3 correlates with the invasive growth potential of breast cancer cells (17, 29). To delineate MTA2’s potential effects on growth, we examined the anchorage-independent growth of T47D cells stably overxpressing MTA2 (Fig. 7A). Estradiol enhanced the ability of T47D vector control-transfected cells to form colonies in soft agar (labeled V1 and V2, E2), and the antiestrogen tamoxifen inhibited this increase in colony formation (V1 and V2, E2+Tam). In contrast, overexpression of MTA2 markedly enhanced anchorage-independent growth in the absence of estrogen (clones MTA2-2.5 and 2.8). Interestingly, the two MTA2-overexpressing clones were also resistant to the growth inhibitory effects of tamoxifen (Tam and E2+Tam).

Fig. 7.

MTA2 overexpression facilitates hormone-independent growth.

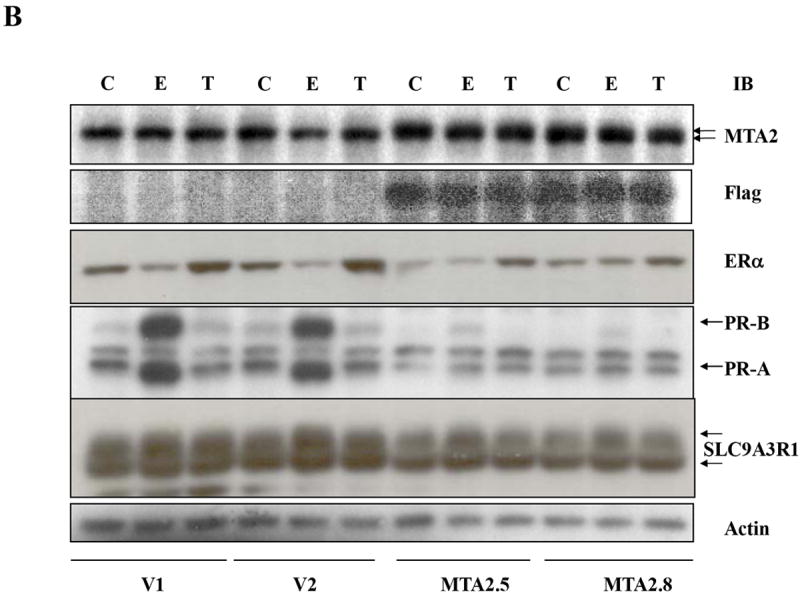

(Panel A). Soft agar assay of two vector control stably transfected T47D cells (V1 and V2) or MTA2 transfected cells (MTA2.5 and MTA2.8) in the presence of vehicle (C), 1nM estradiol (E2), Tam, or E2 + Tam. (B) Immunoblot analysis of the different T47D stable clones with antibodies to MTA2, Flag, ERα, PR-A and B, and SLC9A3R1, and β-actin.

An important question is whether the hormone-independence observed with MTA2 overexpression is associated with a concomitant loss in ERα expression and/or gene regulation. To examine this, we treated vector-control and MTA2 stable T47D transfectants with estrogen or tamoxifen, and performed immunoblot analysis for MTA2, ERα, and the endogenous estrogen-induced proteins, progesterone receptor (PR) A and B isoforms and the sodium/hydrogen exchanger, solute carrier family 9, isoform 3 regulator factor 1 (SLC9A3R1; also called EBP50 or NHERF) (Fig. 6B). Both of these proteins contain estrogen response elements in their promoters which confer estrogen-inducibility (30, 31). The levels of endogenous MTA2 and exogenously-expressed Flag-tagged MTA2 are shown in the upper and second panels, respectively. As previously demonstrated by others (32, 33), the levels of endogenous ERα protein were downregulated with estrogen, and tamoxifen treatment resulted in increased ERα levels in vector-control cells (V1 and V2, E or T, respectively). In contrast, estrogen-induced degradation was not observed in the MTA2 transfectants, however tamoxifen-induced stabilization of the receptor was seen (MTA2.5 and MTA2.8). Actin was utilized as the loading control in this immunoblot analysis. Thus, although ERα expression is maintained in these cells, its regulation appears to be altered. In addition, the MTA2 transfectants have lost or dramatically reduced their ability to induce the PR-A and B isoforms, as well as SLC9A3R1. Of particular note, is that the levels of the PR-A and B isoforms are altered, resulting in a relative excess of PR-A in the transfectants compared to the vector-control cells. These results suggest that the estrogen and tamoxifen-unresponsive phenotype associated with MTA2 overexpression could be mediated through a repression of endogenous ERα-induced gene expression.

DISCUSSION

Breast cancer is one of the most common and lethal female cancers in the United States. It is known that estrogens and ERα play a central role in breast carcinogenesis (34), and this forms the foundation for the use of various hormonal treatment strategies directed toward estrogen depletion, by the use of aromatase inhibitors, or estrogen antagonism via selective estrogen receptor modulators, such as tamoxifen. However the successful use of these strategies is often limited by the development of resistance through the occasional loss of ERα expression (35), or altered growth factor crosstalk and cellular signal transduction pathways (36, 37). It is hoped that a thorough understanding of the molecular basis for estrogen signaling will help us to identify new strategies to thwart the development of resistance in breast cancer patients. Generally, when ERα is bound to tamoxifen, it recruits corepressors and different HDAC complexes to the promoter of estrogen-responsive genes, and thereby attenuates promoter activity (24). It is thought that the steady-state level of acetylation, either at the promoter or of the transcription factor itself, is dictated by the balance of repressors and activator proteins present. The pivotal discoveries that members of the MTA family of proteins, which are present in distinct NURD complexes (15, 27), act as direct modulators of estrogen action and breast cancer growth pathways (17, 29), provides another level of complexity to the negative control of estrogen action.

In this report, we demonstrate that MTA2 is an ERα-binding protein and repressor of estrogen action. MTA2 did not modulate progesterone receptor or androgen receptor transcriptional activities in MCF-7 cells. In addition, MTA2 overexpression renders ERα-positive breast cancer cells unresponsive to hormonal stimulation, the molecular basis of which we do not yet understand, but the phenotype is associated with a loss in estrogen-inducibility of estrogen-regulated genes. Furthermore, we provide evidence that MTA2 overexpression can enhance ERα deacetylation. ERα corepressors, such as N-CoR, are recruited to HDAC complexes (38), probably through their conserved SANT domains (39), suggesting that their repressor functions are related to their associated HDAC activity. Since we are unable to differentiate MTA2’s effects on ERα activity from its known effects on chromatin in these experiments, it is also probable that some of the estrogen-independent effects we observed could be indirect, and occur through its associated HDAC activity. However, we hypothesize that MTA2 represses ERα activity, at least in part, through its enhancement of ERα deacetylation. It is likely that MTA2 dysregulation, as well as ERα deactylation, could prove to play important roles in breast tumor progression.

The HBD of ERα contains a large hydrophobic cleft composed of helixes H3, H5, and H12 that binds coregulatory proteins (40). It has been proposed that corepressors like N-CoR are also capable of binding HBD residues outside of the AF2 core region contained within helix 12 (41, 42). It is well known that receptor coactivators and corepressors compete for binding to the AF2 surface, and hormone binding influences the exchange of these coregulators [reviewed in (43)]. We show that MTA2 interacts with several discrete regions of ERα, including the receptor hinge domain, in a constitutive manner. Although evidence implicates N-CoR and SMRT in ERα antagonist activity, it has been difficult to demonstrate a direct interaction between these two repressors and ERα in the presence of tamoxifen, leading to one hypothesis that other corepressors might be more central for ERα signaling (42). Thus, the MTA family of proteins may prove to serve a fundamental role in the process of breast tumor progression.

There are limited examples where coregulatory proteins bind to separate ERα domains, as we demonstrate here for the MTA2 repressor. Two recently identified coregulators, the coactivator ERBP (44) and the corepressor HET/SAFB (45), bind to residues along the combined DNA and hinge domains. The L7/SPA coactivator interaction domain maps to the ERα hinge domain, and binding of corepressors can interfere with its ability to increase the transcription of tamoxifen-occupied receptors (46). Similarly, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator (PGC-1) interacts with the hinge domain (47). Interestingly, a MTA1-interacting protein named MICoA, which can enhance ERα transcriptional activity, has also been shown to bind to the ERα hinge region, implying a competition mechanism of action with MTA1 (48).

The exact mechanism of MTA2 binding to ERα is currently not known, since the receptor interaction region we identified (MTA2 residues 1-254) does not appear to contain a typical corepressor nuclear receptor (CoRNR) motif (49). It has been shown that MTA1 binds to ERα through a CoRNR motif within MTA1 (17, 50) in a region different from that we find for MTA2, which further highlights the differences between these two MTA family members (20, 51). It has not been shown that MTA3 binds directly to ERα, however, its expression is related to ERα expression in breast cancer cells (18, 29). The amino-terminal BAH domain (52) of MTA2 interacts with ERα, and is present in a number of proteins involved in protein-protein interactions within protein complexes functioning in chromatin replication and transcriptional repression, possibly through its role in DNA methylation (53, 54). Our demonstrated ERα—MTA2 binding is the first eukaryotic example of a protein-protein interaction that involves the BAH domain. However, our study does not exclude the possibility of an interaction between ERα and other MTA2 domains.

We show that MTA2 overexpression results in a reduction in the levels of ERα-responsive genes, similar to that which has been demonstrated for MTA1 overexpression in MCF-7 cells (17). We also observed a relative increase in the PR-A to PR-B isoform ratio in the MTA2 transfectants. We recently reported that an excess of the PR-A isoform in invasive breast cancers was significantly associated with a failure to respond to tamoxifen (55), thus future experiments will be focused on exploring the potential association between PR and MTA2, and response to antiestrogens in these cells. Furthermore it has been shown that MTA1 and MTA3 overexpression results in an increase in invasive properties (17, 29). We have not yet examined invasive pathways in the MTA2 transfectants, however we did observe that these cells were rendered hormone-independent, and exhibited enhanced anchorage-independent growth in vitro. MTA2 overexpression thus could drive cells to the first steps in the progression of estrogen-independence, via a loss in the ability to regulate critical estrogen-induced gene expression. It has been observed that in the progression to hormone independence, different growth factor receptors and possible ligands can be upregulated, leading to autocrine growth regulatory mechanisms. We did not observe increased expression of either the c-Erb-B2 or the epidermal growth factor receptors in the MTA2 transfectants (data not shown). Our results suggest that similar to that demonstrated for MTA1 and the MTA1 short form (50), MTA2 may be a potent regulator of nuclear ERα function. As suggested (56), down-regulation of estrogen receptor signaling by these family members could then be implicated in the loss of MTA3 expression, and subsequent enhanced invasive properties of breast cancer cells. Since the MTA1 and 2 proteins appear to form complexes with a different set of transcription factors (20, 51), and because MTA3 has been associated with the Mi2/NuRD complex (29), the functions of each of the three family members may be distinct. Our observed difference in the region of MTA2 interacting with ERα also supports this supposition. Future studies are required to fully understand the discrete functions and regulatory effects of the MTA family members on the ER signaling pathway.

We also examined the effects of MTA2 expression on the K303R ERα somatic mutation that we identified in premalignant breast lesions (7). This specific alteration appears to be a gain of function mutation, with activation at low concentrations of hormone and altered binding to ERα HAT coactivators. Our previous finding that this ERα lysine residue is acetylated (11), suggests that the K303R somatic mutation might be a useful tool to dissect the role of MTA2 and HDAC in the regulation of ERα acetylation. Our data herein showing that the K303R ERα mutant was refractory to MTA2 inhibition, suggests that acetylation may be one component of the altered phenotype associated with this mutation. It has been reported that the K303R ERα mutation responds to MTA1-mediated transcriptional repression (48), another distinction in function compared to that we report here for the MTA2 family member. This reinforces the concept that the different MTA family members may have distinct effects on ERα signaling.

It is possible that the simply named receptor hinge domain may perform an important role in ERα signaling. Mutations in the hinge domain of the androgen receptor (AR) are frequently present in prostate cancer (57, 58), and this region binds corepressors that govern hormone-dependent AR activity (59). Studies are currently underway in our laboratory to determine the exact frequency of the K303R ERα mutation in invasive breast cancers arising in the United States. Although one group has failed to detect the mutation (60), another laboratory has recently independently confirmed its presence in breast cancers from women in the United States (61). It is intriguing that breast cancer patients in Japan appear to lack the K303R mutation (62), however, it is not known whether this is due to methodological differences with its detection, or to other ethnic differences. Irregardless, the ERα hinge domain appears to be more important than once appreciated. This region denotes a pivotal role between other functional domains. The K303R ERα mutation demonstrates this bifunctional activity with a gain in sensitivity to coactivators (7), but a loss in sensitivity to repressors, such as MTA2. This functional dysbalance may generate a selectable phenotype during breast tumorigenesis. The ERα hinge domain also appears to be a site of phosphorylation by signaling molecules p21-acivated kinase 1 (Pak1) (63) or protein kinase A (PKA) (64), and a binding site for Stat5b (65) and JUN transcription factor proteins (66). Thus, this domain of ERα may also play a key role in regulation of receptor-mediated events. Since several ERα corepressors are also targets themselves of cellular signaling molecules, the process of receptor acetylation, along with coordinate signaling to ERα coregulatory proteins, may be key targets for future therapeutic intervention.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Plasmids and Chemicals

The Xenopus vitellogenin ERE2-tk-luciferase (Luc) reporter, pCMV-β-galactosidase (β-gal) (45), the hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged wild-type and K303R ERα vectors (28), the Flag sequence (DYKDDDDK)-tagged MTA2 plasmid (a kind gift from Wei Gu, Columbia University) (16), glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-fused ERα AF2, DBD, and AF2/hinge domain vectors (45), K302R/K303R ERα (11), and the p300 HAT expression vector (67) have been previously described. GST-ERα hinge domain constructs (residues 253 to 310) with or without the 908 A to G ERα mutation (K303R) were generated through PCR and inserted into the pGEX 4T-1 vector (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) at the Bam HI and EcoRI cloning sites (28). To generate the GST fusion vectors of MTA2, full length MTA2 cDNA was prepared by performing RT-PCR with RNA from MB-MDA-231 breast cancer cells as template. The cDNA was then cut by XhoI combined with Asp718 or EcoRV, and inserted into pGEX 4T-3 vector through the XhoI and NotI sites. The MTA2 constructs used for in vitro translation were cut from Flag-MTA2 by Nde I and Bam HI (full length MTA2), Asp718 (residues 1-253 MTA2), Hind III (residues 1-237 MTA), or EcoRV (residues 1-115 MTA), and inserted into the pET-15b vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) through the Nde I and Bam HI sites. The PRE-Luc and ARE-Luc reporters were kindly provided by Dr. Dancy Wiegel, Baylor College of Medicine, and the RARE-Luc was provided by Dr. Powel Brown, also at Baylor College of Medicine. 8-Br-cAMP was purchased from CALBIOCHEM (La Jolla, CA).

Cell Culture and Transfection

The ERα-positive T47D, MDA-MB-361, BT474, and ERα-negative MDA-MB-231 MDA-MD-435 human breast cancer cells, and HeLa cervical cancer cells were obtained from American Type Tissue Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). ERα-positive MCF-7 human breast cancer cells were previously described (7). All the cell lines were maintained in Minimal Essential Medium (MEM) (InVitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Summit Biotechnology, Fort Collins, CO), 6 ng/ml insulin, 200 units/ml penicillin, and 200 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

For transient transactivation assays, cells were maintained in phenol-red free MEM supplemented with 5% charcoal-stripped FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT) for 5-7 days. One day before transfection, cells were plated in 2 ml media at 2.5 × 105 (MCF-7 and T47D cells) or 0.5 × 105 (HeLa cells) per well in 6-well plates, and then transfected using Fugene 6 reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Each well was transfected with 1 μg different nuclear receptor luciferase reporters, 100 ng pCMV-β-gal vector, and MTA2 and/or ERα expression vectors as indicated. Cells were treated with estrogen (E2, 10-9 M), or1 nM nuclear receptor ligand as indicated in the figure legend, or vehicle for an additional 18-24 hours, then the cells were washed twice with PBS, harvested into 1X reporter lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), and luciferase values as well as β-gal activities were assayed as described (45). ER luciferase activity was normalized by dividing by the β-gal activity to give relative luciferase units (FLU). Experiments were performed in triplicate; the data are presented as the average +/- SEM, and are representative of three independent experiments.

To generate T47D cells stably overexpressing MTA2 or empty vector, 5 μg Flag-MTA2 plasmid or empty vector was transfected with Fugene 6 reagent into 100 mm tissue culture dishes following the manufacturer’s protocol. Stable clones overexpressing MTA2 were selected as described (7), and positive clones were identified using immunoblot analysis with an anti-PID antibody (16).

Colony Formation and Soft Agar Assay

For colony formation assays, 2 × 106 cells (MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231) were plated in 100 mm tissue culture plates 24 hours before transfection to allow for attachment. 5 μg MTA2 expression vector or empty vector was transfected into each plate with Fugene6 reagent following the manufacturer’s protocol. 24 hours after transfection, the cells were incubated with 800 μg/ml G418 antibiotic (InVitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in 5% FBS for 14 days, the colonies were stained with 1% crystal violet, the number of colonies counted under a microscope, and photographed. The data are representative of two independent experiments done in triplicate.

Soft agar assays were performed in six-well plates. Into each well, 1.5 ml of prewarmed (50°C) 0.7% SeaPlaque agarose (FMC, Rockland, ME) was added and dissolved in phenol red-free MEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 5% charcoal stripped FBS (Summit, Fort Collins, CO) to serve as the bottom layer, and allowed to solidify at 4°C until to use. 0.5×104 cells as a single cell suspension were suspended in prewarmed (37°C) of the same media, 4 ml of 0.5 % SeaPlaque agarose was then added, and this suspension plated as the top layer by adding it dropwise to the solidified bottom layer plates. Plates were cooled for 2 hours, and then transferred to a 37°C humidified incubator. Two days after plating, media containing control vehicle, 1nM estradiol, 100 nM 4-hydroxy tamoxifen (OHT), or 1nM estradiol plus 100nM OHT was added to the top cell layer, and the appropriate media was replaced every two days. After 14 days, the colonies were fixed, and the colony number from quadruplicate assays was then counted. The data shown is representative of two independent experiments.

GST-pulldown

GST protein expression and purification procedures on GSH-Sepharose (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) have been described (45). In vitro translation using the TNT transcription-coupled translation system from Promega (Madison, WI), as well as GST pull-down procedures were performed as described (7).

Immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed as described (68) with some modifications. Briefly, HeLa cells were cotransfected with ERα and MTA2 expression vectors and incubated in the absence or presence of 1 nM E2 for 24 hours. High salt cell lysis buffer (7) with 1:100 diluted complete proteinase inhibitor III solution (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) was used to prepare cellular extracts, then these extracts were adjusted to 150 mM NaCl plus 0.2 % NP-40 (binding buffer). After preclearing the extracts with protein G agarose (Sigma, St Louis, MO) [the resultant protein G alone pellet was used as a negative control], the lysates were incubated with HA monoclonal antibody-conjugated agarose (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for another 2 hours to precipitate ERα protein. Subsequently, both the protein G alone, and HA-antibody protein bound beads were washed extensively with binding buffer, the precipitated components were eluted by boiling in SDS loading buffer (125 mM Tris, [pH 6.8], 20% Glycerol [Vol/Vol], 4% SDS, 0.001% Bromophenol blue, 2% 2-ME [Vol/Vol]) resolved by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblotting

Cell extracts or immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were blocked in TBST (20mM Tris [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20) supplemented with 5% non-fat milk (W/V) for 1 hour at room temperature. Anti-PID was a gift from Wei Gu (1:400) (16), anti-ERα clone 6F11 (1:200, Vector Labs, Newcastle, UK), anti-EBP50 (1:250, BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA), anti-HDAC1 clone A19 (1:500), anti-PR clone C19 (1:200) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA), anti-β-Actin AC-15(1:3000) was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and anti-Flag M2 (1:2000; Sigma), antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated with the membranes for 1 hour, the membranes were then washed extensively with TBST buffer, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-mouse IgG (1: 4000); anti-rabbit IgG (1:4000) or anti-goat IgG (1:7500) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), respectively diluted in TBST. After washing five times with TBST, the immunoblot signals were visualized by Enhanced Chemoluminesence reagent (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

In Vitro Acetylation and Deacetylation

GST-p300 HAT and GST-ERα hinge domain proteins were purified as described (69). Briefly, 25 μg GST-ERα hinge protein was acetylated using 400 ng p300 HAT in the presence of 50 nCi 14C-Acetyl-CoA (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Costa Mesa, CA) in 30 μl acetylation buffer (67) at 30°C for 30 minutes (70). The acetylated proteins were immobilized on GSH-Sepharose (Amersham) and washed twice with deacetylation buffer (16). HDAC activity was obtained by eluting with Flag peptide (Sigma). 14C-acetylated protein was incubated with purified Flag-MTA2-associated complexes or control eluate (cell lysates precipitated with only Protein G beads) at 30 °C for 60 minutes in 1X deacetylation buffer as described by (16). The reactions were resolved by SDS-PAGE, the gels were stained with Coomassie Blue dye to evaluate input, and developed using autoradiography.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Twenty-four hours before treatment, T47D cells maintained in phenol-red free MEM supplemented with 5% charcoal-stripped FBS were seeded onto chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL). After treatment with 100 nM E2 or 100 nM 4-hydroxy Tamoxifen (OHT) for 2 hours, cells were fixed for 10 minutes in 4% formaldehyde buffered with PBS at room temperature, and permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS for 4 minutes. Cells were then blocked overnight by PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.05% Triton X-100 at 4°C, and incubated with anti-ERα 6F-11 (anti-mouse, 1:50) and anti-PID (anti-rabbit, 1:200) diluted in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. After extensively washing with PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100, the cells were incubated with Texas Red-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (4μg/ml, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (4μg/ml, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were mounted in Vectashield with 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for nuclear staining (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Fluorescence was monitored with a Zeiss Axioskop2 plus inverted microscope, with DAPI, FITC and Texas-Red filter sets, and an objective setting of 63X.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Gary Chamness for careful review and editing of this manuscript, and Ms. Regina Johnson for excellent administrative assistance.

This work was supported by NIH/NCI R01 CA58183 to SAWF, a Department of Defense Fellowship DAMD17-02-1-0278 to YC. RGP is supported by NIH R01CA70896, R01CA755503, R01 CA86072, and R01CA93596-01.

References

- 1.Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith CL, Conneely OM, O’Malley BW. Modulation of the ligand-independent activation of the human estrogen receptor by hormone and antihormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6120–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuqua SAW, Russo J, Shackney SE, Stearns JM. Estrogen, estrogen receptor and selective estrogen receptor modulators in human breast cancer. J of Women’s Cancer. 2000;2:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKenna NJ, Lanz RB, O’Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocrine Reviews. 1999;20:321–344. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Picard D, Kumar V, Chambon P, Yamamoto KR. Signal transduction by steroid hormones: nuclear localization is differentially regulated in estrogen and glucocorticoid receptors. Cell Regul. 1990;1:291–9. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.3.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson RI, McClelland RA, Robertson JF, Gee JM. Involvement of steroid hormone and growth factor cross-talk in endocrine response in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6:373–87. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuqua SAW, Wiltschke C, Zhang QX, et al. A hypersensitive estrogen receptor-α mutation in premalignant breast lesions. Cancer Research. 2000;60:4026–4029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell. 2000;103:843–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, Lin RJ, Schiltz RL, et al. Nuclear receptor coactivator ACTR is a novel histone acetyltransferase and forms a multimeric activation complex with P/CAF and CBP/p300. Cell. 1997;90:569–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bannister AJ, Kourzarides T. The CBP coactivator is a histone acetyltransferase. Nature. 1996;384:641–643. doi: 10.1038/384641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C, Fu M, Angeletti RH, et al. Direct acetylation of the estrogen receptor alpha hinge region by p300 regulates transactivation and hormone sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18375–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H, Lin RJ, Xie W, Wilpitz D, Evans RM. Regulation of hormone-induced histone hyperacetylation and gene activation via acetylation of an acetylase. Cell. 1999;98:675–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pencil SD, Toh Y, Nicolson GL. Candidate metastasis-associated genes of the rat 13762NF mammary adenocarcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1993;25:165–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00662141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toh Y, Pencil SD, Nicolson GL. A novel candidate metastasis-associated gene, mta1, differentially expressed in highly metastatic mammary adenocarcinoma cell lines. cDNA cloning, expression, and protein analyses. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22958–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, LeRoy G, Seelig HP, Lane WS, Reinberg D. The dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen Mi2 is a component of a complex containing histone deacetylase and nucleosome remodeling activities. Cell. 1998;95:279–89. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo J, Su F, Chen D, Shiloh A, Gu W. Deacetylation of p53 modulates its effect on cell growth and apoptosis. Nature. 2000;408:377–81. doi: 10.1038/35042612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazumdar A, Wang RA, Mishra SK, et al. Transcriptional repression of oestrogen receptor by metastasis-associated protein 1 corepressor. Nature Cell Biology. 2001;3:30–37. doi: 10.1038/35050532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujita N, Kajita M, Taysavang P, Wade PA. Hormonal regulation of metastasis-associated protein 3 transcription in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2937–49. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt JT, Thompson ME, Szabo C, et al. Growth retardation and tumour inhibition by BRCA1. Nat Genet. 1996;12:298–302. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao YL, Yang WM. The metastasis-associated proteins 1 and 2 form distinct protein complexes with histone deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42560–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horlein AJ, Naar AM, Heinzel T, et al. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature. 1995;377:397–404. doi: 10.1038/377397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen JD, Evans RM. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature. 1995;377:454–7. doi: 10.1038/377454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawai H, Li H, Avraham S, Jiang S, Avraham HK. Overexpression of histone deacetylase HDAC1 modulates breast cancer progression by negative regulation of estrogen receptor alpha. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:353–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu XF, Bagchi MK. Recruitment of distinct chromatin-modifying complexes by tamoxifen-complexed estrogen receptor at natural target gene promoters in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15050–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Futamura M, Nishimori H, Shiratsuchi T, Saji S, Nakamura Y, Tokino T. Molecular cloning, mapping, and characterization of a novel human gene, MTA1-L1, showing homology to a metastasis-associated gene, MTA1. J HUm Genet. 1999;44:52–56. doi: 10.1007/s100380050107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brzozowski A, Pike ACW, Dauter A, et al. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature. 1997;389:753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Ng HH, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Bird A, Reinberg D. Analysis of the NuRD subunits reveals a histone deacetylase core complex and a connection with DNA methylation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1924–35. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui Y, Zhang M, Pestell R, Curran EM, Welshons WV, Fuqua SAW. Phosphorylation of estrogen receptor α blocks its acetylation and regulates estrogen sensitivity. Cancer Research. 2004;64:9199–9208. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujita N, Jaye DL, Kajita M, Geigerman C, Moreno CS, Wade PA. MTA3, a Mi-2/NuRD complex subunit, regulates an invasive growth pathway in breast cancer. Cell. 2003;113:207–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savouret J-F. Interplay between estrogens, progestins, retinoic acid and AP-1 on a single regulatory site in the progesterone receptor gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:28955–28962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ediger TR, Park SE, Katzenellenbogen BS. Estrogen receptor inducibility of the human Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor/ezrin-radixin-moesin binding protein 50 (NHE-RF/EBP50) gene involving multiple half-estrogen response elements. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1828–39. doi: 10.1210/me.2001-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nawaz Z, Lonard DM, Dennis AP, Smith CL, O’Malley BW. Proteasome-dependent degradation of the human estrogen receptor. Biochemistry. 1999;96:1858–1862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wijayaratne AL, McDonnell DP. The human estrogen receptor-alpha is a ubiquitinated protein whose stability is affected differentially by agonists, antagonists, and selective estrogen receptor modulators. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35684–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henderson BE, Ross R, Bernstein L. Estrogens as a cause of human cancer. Cancer Research. 1988;48:246–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuqua SAW. The role of estrogen receptors in breast cancer metastasis. J Mam Gland Bio Neoplasia. 2002;6:407–417. doi: 10.1023/a:1014782813943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osborne CK, Bardou V, Hopp TA, et al. Role of the estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 (SRC-3) and HER-2/neu in tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:353–61. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.5.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellis MJ, Coop A, Singh B, et al. Letrozole is more effective neoadjuvant endocrine therapy than tamoxifen for ErbB-1- and/or ErbB-2-positive, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: evidence from a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3795–3797. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.18.3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heinzel T, Lavinsky RM, Mullen TM, et al. A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature. 1997;387:43–8. doi: 10.1038/387043a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Humphrey GW, Wang Y, Russanova VR, et al. Stable histone deacetylase complexes distinguished by the presence of SANT domain proteins CoREST/kiaa0071 and Mta-L1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6817–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiau AK, Barstad D, Loria PM, et al. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell. 1998;95:927–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jung DJ, Lee SK, Lee JW. Agonist-dependent repression mediated by mutant estrogen receptor alpha that lacks the activation function 2 core domain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37280–3. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106860200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang HJ, Norris JD, McDonnell DP. Identification of a negative regulatory surface within estrogen receptor alpha provides evidence in support of a role for corepressors in regulating cellular responses to agonists and antagonists. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1778–92. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes and development. 2000;14:121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bu H, Kashireddy P, Chang J, et al. ERBP, a novel estrogen receptor binding protein enhancing the activity of estrogen receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317:54–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oesterreich S, Zhang Q, Hopp T, et al. Tamoxifen-bound estrogen receptor (ER) strongly interacts with the nuclear matrix protein HET/SAF-B, a novel inhibitor of ER-mediated transactivation. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:369–81. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.3.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jackson TA, Richer JK, Bain DL, Takimoto GS, Tung L, Horwitz KB. The partial agonist activity of antagonist-occupied steroid receptors is controlled by a novel hinge domain-binding coactivator L7/SPA and the corepressors N/CoR or SMRT. Molecular Endocrinology. 1997;11:693–705. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tcherepanova I, Puigserver P, Norris JD, Spiegelman BM, McDonnell DP. Modulation of estrogen receptor-alpha transcriptional activity by the coactivator PGC-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16302–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mishra SK, Mazumdar A, Vadlamudi RK, et al. MICoA, a novel metastasis-associated protein 1 (MTA1) interacting protein coactivator, regulates estrogen receptor-alpha transactivation functions. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19209–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu X, Lazar MA. The CoRNR motif controls the recruitment of corepressors by nuclear hormone receptors. Nature. 1999;402:93–6. doi: 10.1038/47069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar R, Wang RA, Mazumdar A, et al. A naturally occurring MTA1 variant sequesters oestrogen receptor-alpha in the cytoplasm. Nature. 2002;418:654–7. doi: 10.1038/nature00889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bowen NJ, Fujita N, Kajita M, Wade PA. Mi-2/NuRD: multiple complexes for many purposes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677:52–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicolas RH, Goodwin GH. Molecular cloning of polybromo, a nuclear protein containing multiple domains including five bromodomains, a truncated HMG-box, and two repeats of a novel domain. Gene. 1996;175:233–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)82845-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goodwin GH, Nicolas RH. The BAH domain, polybromo and the RSC chromatin remodelling complex. Gene. 2001;268:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Callebaut I, Courvalin JC, Mornon JP. The BAH (bromo-adjacent homology) domain: a link between DNA methylation, replication and transcriptional regulation. FEBS Lett. 1999;446:189–93. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hopp TA, Weiss HL, Hilsenbeck SG, et al. Breast cancer patients with progesterone receptor PR-A-Rich tumors have poorer disease-free survival rates. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2751–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar R. Another tie that binds the MTA family to breast cancer. Cell. 2003;113:142–3. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gottlieb B, Beitel LK, Wu JH, Trifiro M. The androgen receptor gene mutations database (ARDB): 2004 update. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:527–33. doi: 10.1002/humu.20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fu M, Rao M, Wang C, et al. Acetylation of androgen receptor enhances coactivator binding and promotes prostate cancer cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8563–75. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8563-8575.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Q, Lu J, Yong EL. Ligand- and coactivator-mediated transactivation function (AF2) of the androgen receptor ligand-binding domain is inhibited by the cognate hinge region. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7493–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tebbit CL, Bentley RC, Olson JA, Jr, Marks JR. Estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) mutant A908G is not a common feature in benign and malignant proliferations of the breast. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;40:51–4. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Conway K, P E, Edmiston S, et al. Presence of the estrogen receptor alpha A908G (K303R) mutation in invasive breast tumors of the Carolina breast cancer study. 12th SPORE Investigator’s Workshop; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tokunaga E, Kimura Y, Maehara Y. No hypersensitive estrogen receptor-alpha mutation (K303R) in Japanese breast carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;84:289–92. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000019963.67754.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang RA, Mazumdar A, Vadlamudi RK, Kumar R. P21-activated kinase-1 phosphorylates and transactivates estrogen receptor-alpha and promotes hyperplasia in mammary epithelium. Embo J. 2002;21:5437–47. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cui Y, Zhang M, V M, Hopp T, Sukumar S, Fuqua SAW. The K303R ERalpha breast cancer-specific mutation resides at a site of coupling ER acetylation and phosphorylation. Proc Am Assoc Can Res. 2003;44:178A. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bjornstrom L, Kilic E, Norman M, Parker MG, Sjoberg M. Cross-talk between Stat5b and estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta in mammary epithelial cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 2001;27:93–106. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0270093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Teyssier C, Belguise K, Galtier F, Chalbos D. Characterization of the physical interaction between estrogen receptor alpha and JUN proteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36361–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101806200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bordoli L, Husser S, Luthi U, Netsch M, Osmani H, Eckner R. Functional analysis of the p300 acetyltransferase domain: the PHD finger of p300 but not of CBP is dispensable for enzymatic activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4462–71. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.21.4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nishitani J, Nishinaka T, Cheng CH, Rong W, Yokoyama KK, Chiu R. Recruitment of the retinoblastoma protein to c-Jun enhances transcription activity mediated through the AP-1 binding site. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5454–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ogryzko VV, Schlitz RL, Russanova V, Howard BH, Nakatani Y. The transcriptional coactivators p300 and CBP are histone acetyltransferases. Cell. 1996;87:953–959. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)82001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang C, Fu M, Pestell RG. Histone acetylation/deacetylation as a regulator of cell cycle gene expression. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;241:207–16. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-646-0:207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]