Abstract

Patient: Male, 49

Final Diagnosis: Generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the setting of vitamin B12 deficiency and elevated folate levels

Symptoms: Seizures

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: None

Specialty: Neurology

Objective:

Unknown ethiology

Background:

Vitamin B12 deficiency leads to abnormal myelination or demyelination, resulting in sub-acute combined degeneration, peripheral neuropathy, and psychiatric problems, including delusions, hallucinations, cognitive changes, depression, and dementia. Vitamin B12 deficiency also leads to brain shrinkage and neurodegenerative disorders.

Case Report:

We report the case of a 49-year-old man presenting with new-onset seizures one and a half years following subtotal gastrectomy due to stage IV gastric adenocarcinoma. The patient did not have any history of head injury. Laboratory tests were negative for any metabolic derangements. There were no signs of infection. MRI brain and EEG were normal and there were no changes in medications.

Conclusions:

In case of unexplained new-onset seizures, patients should be tested for vitamin B12 and folic acid levels and these should be done as part of the initial work-up.

MeSH Keywords: Folic Acid, Gastrectomy, Seizures, Vitamin B 12 Deficiency

Background

Vitamin B12 deficiency is known to cause a broad range of neurological (central and peripheral), psychiatric, and hematologic manifestations. Few cases of vitamin B12 deficiency have been reported as the cause of seizures. However, here, we report a case of seizures in a patient with both vitamin B12 deficiency and elevated folate levels, without other findings suggestive of vitamin B12 deficiency. Following supplementation of Vitamin B12 and normalization of folic acid level, no further seizure episodes were reported.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with stage IV gastric adenocarcinoma status after subtotal gastrectomy and splenectomy, with metastasis to liver that resolved with chemotherapy and right internal jugular venous thrombosis on lifelong Coumadin presented with an episode of witnessed generalized tonic clonic seizures lasting for 8 minutes at the grocery store. At the scene his finger-stick glucose was 159 mg/dl and he received intravenous lorazepam, and then was rushed to the emergency room. There was no history of previous seizures, substance abuse, or head injury. He had a brief post-ictal period, and then he started to feel better gradually. He denied fever, chills, sick contacts, chest pain, or palpitation prior to this episode. Physical examination was unremarkable apart from an abdominal scar. Computed tomography (CT) brain and cervical spine without contrast was normal. Laboratory findings showed mild anemia with Howell-Jolly bodies and thrombocytosis. Renal functions and electrolytes were normal. Vitamin B12 level was low and folic acid levels were elevated. MRI brain with and without contrast were normal (Figures 1–3) and EEG was also normal.

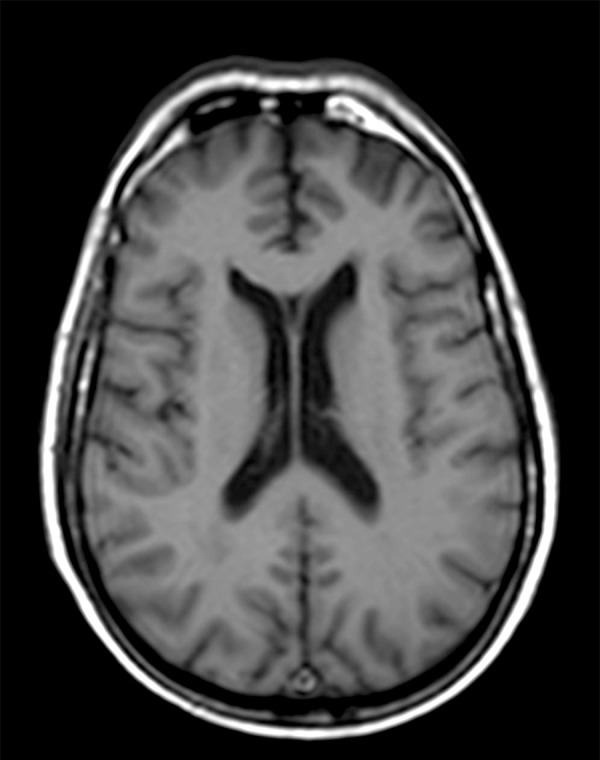

Figure 1.

MRI without contrast T1: normal.

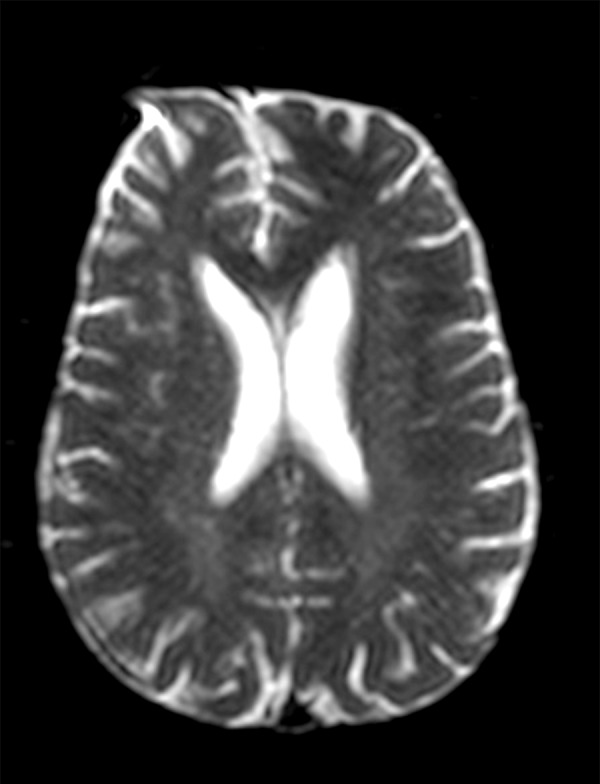

Figure 3.

MRI without contrast diffusion-weighted image: normal.

Review of medical records revealed that 6 months following partial gastrectomy, the level of vitamin B12 was 1063 pg/mL (200–1100 pg/mL) and folate was >>25 ng/mL (5.9–24.8 ng/mL). One and a half years after the surgery, when patient presented with an episode of witnessed seizure, the level of vitamin B12 was low (142 pg/mL). Folate and methylmalonic acid levels were elevated at >>25 ng/mL (5.9–24.8 ng/mL) and 1090 nmol/L (87–318 nmol/L), respectively. Homocysteine level was not checked at this time. Parietal and intrinsic factor antibodies were negative. Vitamin B12 deficiency was diagnosed secondary to malabsorption following subtotal gastrectomy. The patient was started on intramuscular cyanocobalamin and was discharged with Levetiracetam. Vitamin B12 levels after about 6 months of vitamin injections were normal. Levels of methylmalonic acid, folate, and homocysteine were also checked at this time and were found to be within normal ranges (<0.15 nmol/L, 15 ng/mL, and 6.9 umol/L, respectively).

The patient took Levetiracetam for 5 months from the time of discharge and was off Levetiracetam for another 5 months. However, he remained seizure free during the period he was off Levetiracetam.

Discussion

It is well known that Vitamin B12 deficiency leads to abnormal myelination or demyelination, resulting in sub-acute combined degeneration, peripheral neuropathy, and psychiatric problems along with hematologic manifestations. As reported by Meng et al. [1] and Naha et al. [2] that vitamin B12 deficiency can be a cause of generalized tonic colic seizures, we here report another rare case of vitamin B 12 deficiency-induced generalized tonic colic seizures, but in our case the patient also had elevated folate levels and no other neuropsychiatric or hematologic findings except mild normocytic anemia. The elevated folate levels can also be a cause of seizure, as supported by animal studies [3–5].

Folic acid and vitamin B12 are sources of various coenzymes involved in one-carbon metabolism. During this metabolic pathway, tetrahydrofolate (THF) is converted to methylene-THF, after receiving one carbon unit from serine or glycine. Methylene THF can then be used for DNA synthesis by producing thymidine, purine synthesis following oxidation to form formyl-THF, or reduction to methyl THF converting homocysteine to methionine. The conversion of homocysteine to methionine occurs by vitamin B12 containing enzyme methyltransferase [6]. The transfer of a methyl group by methyl THF to homocysteine, forming methionine, ultimately regenerates THF by methionine synthetase, completing one-carbon metabolism.

With B12 deficiency, conversion of methylene THF to methyl THF is irreversible, leading to accumulation methyl-THF and folate trapping [2].

Vitamin B12 has a significant role in formation and maintenance of the myelin sheath of both the central and peripheral nervous systems. Vitamin B12 deficiency leads to abnormal myelination or demyelination, resulting in sub-acute combined degeneration, peripheral neuropathy, and psychiatric problems, including delusions, hallucinations, cognitive changes, depression, and dementia. Vitamin B12 deficiency also leads to brain shrinkage and neurodegenerative disorders.

Vitamin B12 deficiency interferes with the one-carbon cycle and generation of methionine, which synthesizes myelin and neurotransmitters. It also causes homocysteinemia, which may lead to brain damage and cognitive disturbance [6]. Vitamin B12 deficiency leads to methylmalonic acid generation, which is a myelin destabilizer.

Since vitamin B12 is involved in myelin formation, defective myelin may lead to an exaggerated effect of glutamate, which is the principal excitatory neurotransmitter, leading to epileptogenesis [2], as supported by animal studies [7] in which chronic use of methylcobalamin had a protective effect against NMDA receptor-mediated glutamate cytotoxicity on cortical neurons.

Homocysteine elevation, which occurs in vitamin B12 deficiency, has been demonstrated to be epileptogenic, and may have been another cause of new-onset seizures in our patient. Animal studies involving adult and immature rats proved that elevated levels of homocysteine and its metabolic product, homocysteic acid, are epileptogenic, with variation in seizure patterns with age [8–10]. Animal studies involving immature rats revealed an anti-convulsant action of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA-receptor antagonists against seizures induced by homocysteine and homocysteic acid [11,12].

Combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria have been associated with epilepsy and EEG abnormalities due to cobalamin C/D deficiency, possibly due to elevated homocystinuria [13].

Folate and its derivatives are proven to be epileptogenic through their excitatory properties in the central nervous system [14].

The risk of epileptic seizures is small in patients with an intact blood-brain barrier since folate entry is prohibited. However, the epileptogenic potential increases with higher doses of administration and prolonged period of administration [3–5]. The exact mechanism remains unclear; however, it is postulated that it is secondary to reversal of GABA-mediated inhibition [15]. It is proposed that vitamin B12 deficiency leading to the accumulation of methyl THF is epileptogenic, as seen in animal studies in which IV folate administration induced seizures only if administered in very large doses. However, with compromised integrity of the blood-brain barrier via heat lesion or trauma, much lower doses would have similar effects [16].

Starting an antiepileptic drug following the first seizure episode in our patient was controversial, as many neurologists start antiepileptic drugs after a second seizure episode in an unprovoked seizure. However, in our case, at the time of admission the patient was thought to have metastatic disease before the MRI result was obtained and, due to severity of the attack, starting Levetiracetam was justified. The diagnosis of B12 deficiency-induced seizure was made retrospectively during follow-up. Recent guidelines regarding the “Management of an unprovoked first seizure in adults” support our decision [17].”

Conclusions

It is important to identify and consider rare causes of unexplained new-onset seizures to allow appropriate treatment and avoid unnecessary use of anti-epileptic medications. Anti-epileptic drugs are associated with multiple adverse effects, including lowering of vitamin B12 levels. This is particularly important when the cause of seizures is vitamin B 12 deficiency. We emphasize including vitamin B12 and folate levels in the initial workup of a patient with new-onset seizures. There is need to further investigate whether elevated folate in conjunction with Vitamin B12 deficiency is a cause of epilepsy.

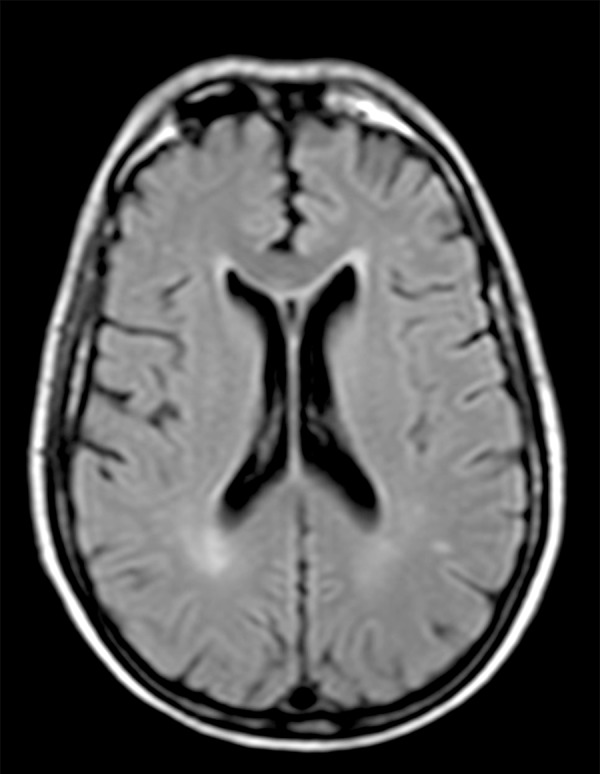

Figure 2.

MRI without contrast T2: normal.

Footnotes

Statement

There are no financial grants or funding sources to declare. There is no conflict of interest for any authors of this manuscript.

References:

- 1.Meng L, Hong-Shiu C, Hsiao-Ting W, et al. Intractable epilepsy as the presentation of vitamin B12 deficiency in the absence of macrocytic anemia. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1147–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.66204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naha K, Dasari S, Vivek G, Prabhu M. Vitamin B12 deficiency: an unusual cause for recurrent generalised seizures with pancytopaenia. BMJ Case Rep, 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-006632. pii: bcr2012006632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynolds EH. Benefits and risks of folic acid to the nervous system. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72(5):567–71. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.5.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shorvon SD, Carney MW, Chanarin I, Reynolds EH. The neuropsychiatry of megaloblastic anaemia. Br Med J. 1980;281(6247):1036–38. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6247.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spaans F. No effect of folic acid supplement on CSF folate and serum vitamin B12 in patients on anticonvulsants. Epilepsia. 1970;11(4):403–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1970.tb03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selhub J. Folate, vitamin B12 and vitamin B6 and one carbon metabolism. J Nutr Health Aging. 2002;6(1):39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akaike A, Tamura Y, Sato Y, Yokota T. Protective effects of a vitamin B12 analog, methylcobalamin, against glutamate cytotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;241(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90925-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubová H, Folbergrová J, Mares P. Seizures induced by homocysteine in rats during ontogenesis. Epilepsia. 1995;36(8):750–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mares P, Folbergrová J, Langmeier M, et al. Convulsant action of D, L-homocysteic acid and its stereoisomers in immature rats. Epilepsia. 1997;38(7):767–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marangos PJ, Loftus T, Wiesner J, et al. Adenosinergic modulation of homocysteine-induced seizures in mice. Epilepsia. 1990;31(3):239–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1990.tb05371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folbergrová J. Anticonvulsant action of both NMDA and non-NMDA receptor antagonists against seizures induced by homocysteine in immature rats. Exp Neurol. 1997;145(2 Pt 1):442–50. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folbergrová J, Haugvicová R, Mares P. Behavioral and metabolic changes in immature rats during seizures induced by homocysteic acid: the protective effect of NMDA and non-NMDA receptor antagonists. Exp Neurol. 2000;161(1):336–45. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biancheri R, Cerone R, Rossi A, et al. Early-onset cobalamin C/D deficiency: epilepsy and electroencephalographic features. Epilepsia. 2002;43(6):616–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.24001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reynolds EH, Gallagher BB, Mattson RH, et al. Relationship between serum and cerebrospinal fluid folate. Nature. 1972;240(5377):155–57. doi: 10.1038/240155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies J, Watkins JC. Facilitatory and direct excitatory effects of folate and folinate on single neurones of cat cerebral cortex. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22(13):1667–68. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hommes OR, Obbens EA, Wijffels CC. Epileptogenic activity of sodium-folate and the blood-brain barrier in the rat. J Neurol Sci. 1973;19(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(73)90057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krumholz A, Wiebe S, Gronseth GS, et al. Evidence-based guideline: Management of an unprovoked first seizure in adults: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2015;84(16):1705–13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]