Abstract

Transgenic mice, containing a chimeric gene in which the cDNA for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP) (PEPCK-C) (EC 4.1.1.32) was linked to the α-skeletal actin gene promoter, express PEPCK-C in skeletal muscle (1–3 units/g). Breeding two founder lines together produced mice with an activity of PEPCK-C of 9 units/g of muscle (PEPCK-Cmus mice). These mice were seven times more active in their cages than controls. On a mouse treadmill, PEPCK-Cmus mice ran up to 6 km at a speed of 20 m/min, whereas controls stopped at 0.2 km. PEPCK-Cmus mice had an enhanced exercise capacity, with a VO2max of 156 ± 8.0 ml/kg/min, a maximal respiratory exchange ratio of 0.91 ± 0.03, and a blood lactate concentration of 3.7 ± 1.0 mm after running for 32 min at a 25° grade; the values for control animals were 112 ± 21 ml/kg/min, 0.99 ± 0.08, and 8.1 ± 5.0 mm respectively. The PEPCK-Cmus mice ate 60% more than controls but had half the body weight and 10% the body fat as determined by magnetic resonance imaging. In addition, the number of mitochondria and the content of triglyceride in the skeletal muscle of PEPCK-Cmus mice were greatly increased as compared with controls. PEPCK-Cmus mice had an extended life span relative to control animals; mice up to an age of 2.5 years ran twice as fast as 6 −12-month-old control animals. We conclude that overexpression of PEPCK-C repatterns energy metabolism and leads to greater longevity.

PEPCK-C2 is involved in gluconeogenesis in the liver and kidney cortex and in glyceroneogenesis in liver and white and brown adipose tissue (see Ref. 1 for a review). However, this enzyme is also present in a broad variety of mammalian tissues (2), including the small intestine, colon, mammary gland, adrenal gland, lung, and muscle; its metabolic role in these tissues remains obscure. To study the physiological function of PEPCK-C, the gene has been overexpressed or ablated in specific tissues of the mouse. When PEPCK-C was overexpressed in white adipose tissue, the mice had increased rates of glyceroneogenesis in their adipose tissue and became obese (3).In contrast, ablating the expression of PEPCK-C in adipose tissue resulted in mice with lipodystrophy (4). However, a systematic study involving other mammalian tissues where the enzyme has been detected has not been undertaken.

We have overexpressed the gene for PEPCK-C in the skeletal muscle of transgenic mice to test the metabolic and physiological consequences. Skeletal muscle was selected as a target organ because there is no clear indication of the metabolic outcome of having a high activity of PEPCK-C in this tissue. Skeletal muscle does not synthesize and release glucose, although there have been reports over the years that the tissue can make glycogen de novo since both PEPCK-C and fructose-1–6-bisphosphatase activities have been found in skeletal muscle (5, 6). We have evidence from research ongoing in our laboratory3 that glyceroneogenesis occurs in skeletal muscle. This pathway is an abbreviated version of gluconeogenesis, which involves the synthesis of glycerol-3-phosphate (used for triglyceride synthesis) from precursors other than glucose and glycerol. However, glyceroneogenesis has not previously been reported to occur in skeletal muscle, so the extent of the metabolic effect of overexpressing PEPCK-C in this tissue was not immediately apparent.

PEPCK-C is a major cataplerotic enzyme (7). However, it is also capable of synthesizing oxalacetate, thus replenishing the citric acid cycle, so it has the potential of being an anaplerotic enzyme. In either case, it would be predicted that increasing the activity of PEPCK-C in skeletal muscle would increase citric acid cycle flux in the animal; ablation of hepatic PEPCK-C greatly reduces citric acid cycle flux (8). This is especially important in tissues such as skeletal muscle, in which the levels of citric acid cycle intermediates vary widely during strenuous exercise to accommodate the major increase in total cycle flux that is required to generate the energy to support muscle contraction. An increase in citric acid cycle anions occurs largely due to anaplerosis. However, any four or five carbon intermediate that enters the citric acid cycle must be removed since it cannot be completely oxidized to carbon dioxide in the cycle. It is thus likely that PEPCK-C contributes to both the generation and the subsequent removal of citric acid cycle anions (7). If this is the case, the enzyme is an important component of citric acid cycle function in muscle. Until this study, the concept of a critical role of PEPCK-C in energy metabolism in mammalian skeletal muscle has not been tested.

Our results indicate that transgenic mice that overexpress the gene for PEPCK-C (about 9 units/g of muscle) have a greatly enhanced level of physical activity, which extends well into old age (24 months or older). This is due, in part, to an increased number of mitochondria and a high concentration of triglyceride in their skeletal muscles. The mice overexpressing the gene for PEPCK-C also have very little body fat, despite eating 60% more than controls. The biochemical basis for this effect was investigated.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation and Analysis of Transgenic Mice

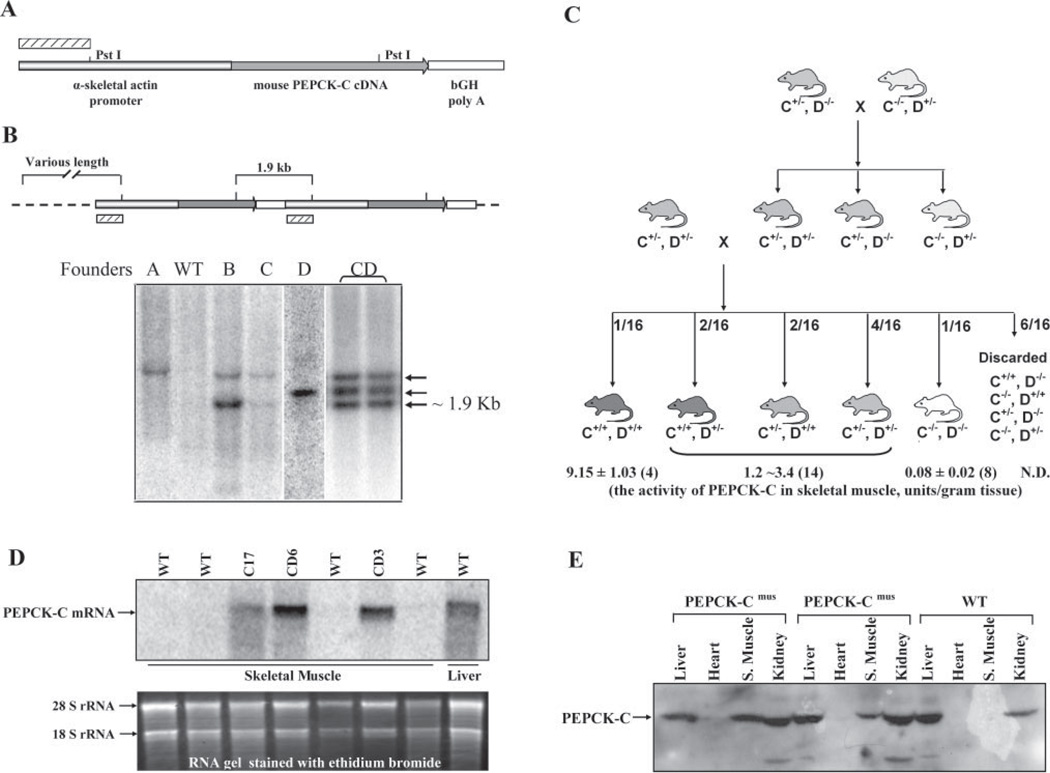

A chimeric gene was constructed that included 2 kb of the α-skeletal actin gene promoter (9) that was linked to a 1976-bp segment of the cDNA for PEPCK-C from the mouse followed by a 710-bp fragment of the 3′-untranslanted region of the bovine growth hormone (bGH) mRNA (see Fig. 1A). The α-skeletal actin gene promoter was a kind gift from Dr. Laurence H. Kedes (University of Southern California). This gene promoter was selected since it has been shown to limit the transcription of linked structural genes to skeletal muscle, with a low level of expression in brown adipose tissue (10). The mice were produced at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine Transgenic Mouse Core Facility by a procedure described in detail previously (11, 12). Of the 34 mice that were produced, six positive founders, designated as lines A, B, C, D, E, and F, were identified by Southern blotting. DNA was isolated from the tails of the mice by lysis overnight at 55 °C in a buffer containing 50 mm KCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 0.1% gelatin, 0.45% Nonidet P-40, 0.45% Tween 20, and 24 mg/ml proteinase K. The DNA was digested with PstI, and the resulting fragments were separated by electrophoresis using 1% agarose gel and transferred to Gene Screen Plus® (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). A 690-bp fragment of the human α-skeletal actin gene promoter (Fig. 1A), which showed no significant homology to sequences in the mouse genome, as judged by National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BLAST prediction, was used as a hybridization probe. To increase the activity of PEPCK-C in the skeletal muscle, founder lines C and D were bred together to create a new line, designated as line CD (see Fig. 1C). Homozygous mice in the line CD (C+/+, D+/+) were used for most of the experiments.

FIGURE 1. Generation of PEPCK-Cmus mice.

A, a chimeric gene containing 2 kb of the human α-skeletal actin gene promoter, linked to the cDNA for PEPCK-C from the mouse followed by the 3′-end of bGH (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). The hatched bar represents the DNA probe that was used for Southern blotting genomic DNA from the mice. B, a schematic illustration of two copies of the transgene integrated into the host cell genome. PstI digestion of genomic DNA results in a 1.9-kb fragment and fragments of various lengths, depending upon the location of other PstI sites in the genome. The hatched bar represents the DNA probe that was used for Southern blotting genomic DNA from the mice. The Southern blot shown in B is for DNA from founder lines A, B, C, D, and wild type (WT) mice. The pattern of DNA for the cross between founder lines C and D (CD) is also shown in the last two lanes; the homozygous CD mice are termed PEPCK-Cmus mice. C, a schematic representation of the CD cross to generate the PEPCK-Cmus mice used in these studies. This panel illustrates the level of activity of PEPCK-C in the skeletal muscle of mice at various stages of interbreeding. Mice heterozygous for either the C or the D genotypes had an activity of PEPCK-C between 1.2 and 3.4 units/g of skeletal muscle (it was not possible to distinguish between the specific genotypes of these mice by Southern blotting). The values for the activity of PEPCK-C for the PEPCK-Cmus mice and wild type animals are presented as the mean ± the S.E. of the mean for the number of mice shown in parentheses. D, a Northern blot of the PEPCK-C mRNA in the skeletal muscle of CD mice and control animals (WT). The PEPCK-C mRNA in the liver is also presented as a positive control. E, a Western blot of the PEPCK-C from the liver, heart, kidney, and skeletal muscle (S. Muscle) of PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls (WT).

Animal Care

The mice were maintained in the Case Western Reserve University Animal Resource facility, under the supervision of full-time veterinarians. The research described in this study was approved by the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

RNA Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from mouse tissues using the QuickPrep total RNA kit (Amersham Biosciences) (13), and Northern blotting was performed as described in detail previously (13). Briefly, 20 µg of total RNA was separated by electrophoresis on an agarose gel, transferred to Gene Screen Plus membrane, and hybridized with a 1.0-kb SmaI fragment of the PEPCK-C cDNA. The DNA probe was labeled using [α-32P]dATP.

Determination of PEPCK-C

Various mouse tissues were homogenized in 0.25 m sucrose, containing 5 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, and 1 mm dithiothreitol. A cytosol fraction, prepared by centrifuging the homogenate at 30,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, was used to determine the activity of PEPCK-C by the method of Ballard and Hanson (14). The levels of PEPCK-C from liver, heart, kidney, and skeletal muscle were determined using Western blotting. The antibody to PEPCK-C was kindly provided by Dr. F. J. Ballard (Adelaide, Australia).

Assay of Metabolites in the Blood and Tissues

Mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of avertin (0.5 ml of 20 mg/ml solution/25 g of body weight). The concentration of glucose in the blood was determined using an Encore® glucometer (Bayer Corp). Plasma was generated from whole blood using MICROTAINER® plasma separator tubes (BD Biosciences). The concentration of triglyceride, fractionated bilirubin, β-hydroxybutyrate, albumin, total protein, blood urea nitrogen, cholesterol, creatinine, creatine kinase, triglyceride, and free fatty acid was determined by Veterinary Diagnostic Services (Marshfield Laboratories).

Muscle triglycerides were extracted using a modification of the method of Folch et al. (15). Briefly, fresh muscle samples were freed from any visible non-muscle material and weighed out in duplicate. Each sample was homogenized via IKA-ULTRA-TURRAX T 25 basic tissue blender, and total lipids were extracted by incubating the tissue homogenate in a 2:1 chloroform:methanol solution for 48 h at 4 °C. The two phases were further defined by the addition of MgCl2 and centrifugation. The supernatant was extracted and discarded, and the remaining layer was taken to dryness under air. The triglycerides were saponified using methanolic KOH (0.5 n) at 70 °C for 75 min, acidified with 6 n HCl. The resulting fatty acids were extracted three times with hexane. The aqueous phase containing glycerol was dried using a Labconco CentriVap concentrator at 25 °C. The concentration of glycerol was determined using a fluorometric assay essentially as described by Wieland (16); that value was used for the calculation of the concentration of triglyceride in the tissue.

Home Cage Activity Testing

All mice were individually caged 6 weeks prior to the onset of behavioral testing. Prior to home cage activity measurements, the mice were observed in their cages for 15 min, three times a day, to rule out unusual behaviors that could confound the home cage activity measurements, such as locomotor or grooming stereotypy, tremors, unusual nest building, and overall locomotor function (unusual gait events). Two observations were carried out during the light phase, and one was carried out during the dark phase. Five mice were observed at each 15-min time point, with each animal being observed for 30-s intervals.

All of the mice were brought into the testing room 24 h prior to the onset of testing for acclimatization to the room and testing conditions, which included the replacement of the standard water/food holding top with a clear top and placing feed and fluid source (Hydrogel®) inside the cage. All mice were tested during the same trial. Animal cages were placed on a table directly below a charged-coupled device (CCD) camera (Panasonic), and observations were carried out for 22 h, consecutively, starting at 3 p.m. and concluding at 1 p.m., using a tracking system (Noldus, Ethovision 3.1 Pro, Leesburg, VA). Distance traveled, velocity, and number of rearings as well as turn angle and angular velocity (to further rule out stereotypy-related running) were automatically calculated by the tracking system. Data were nested in 1-h intervals to simplify statistical analysis. Upon termination of testing, wire tops with standard food and water were placed back on the cages, and the mice were returned to their housing room.

Maximal Exercise Capacity

Exercise performance and exercise capacity were determined in fed, gender-matched, and age-matched PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls. The mice were subjected to strenuous exercise on a rodent treadmill (Columbus Instruments Oxymax System, Columbus, OH) using standard exercise running tests to evaluate aerobic capacity (VO2max), maximal running endurance, and maximal running speed. To encourage the mice to run, the treadmill was equipped with an electrical shock grid at the rear of the treadmill. The shock grid was set to deliver 0.2 mA, which caused an uncomfortable shock but did not physically harm or injure the animals. When the mice reached exhaustion, as defined by their inability to run for 10 s, the electric shock was discontinued.

Types of Treadmill Testing

We included three types of strenuous exercise measurements (treadmill testing) in this study. First, we assessed the ability of untrained PEPCK-Cmus and control mice to run for distance. The animals were initially acclimated to the treadmill environment for 30 min. For warm-up and for further familiarization with treadmill running, the mice were required to run at a relatively easy pace of 10 m/min for 30 min. Then the speed of the treadmill was increased to 20 m/min, and we recorded the exercise duration and distance the mice could run until exhaustion. Exhaustion was defined operationally as the time at which the mouse was unable, or refused, to maintain its running speed despite encouragement by mild electrical stimulation.

Second, we determined the VO2max of both types of mice. Prior to running, the mice were acclimated to the enclosed treadmill and its surroundings for 60 min. During this period, measurements of whole body oxygen consumption VO2, carbon dioxide production VCO2, and the respiratory exchange ratio (RER) were obtained while the animals rested quietly. The mice then began walking on the treadmill at a speed of 5 m/min and a grade of 0° for a 10 min warm-up. The grade of the treadmill was then set to 25°, and the speed was increased 2 m/min every 2 min until the mouse reached exhaustion. Both VO2 and VCO2 were monitored continuously throughout the exercise test. Substrate utilization during exercise was assessed from the RER data. A blood sample was taken before and after exercise for the determination of lactate.

Third, PEPCK-Cmus and control mice of various ages were acclimated to the treadmill for 30 min followed by a 30-min warm-up period at a treadmill speed of 10 m/min (set at a grade of 0°). We then increased the speed of the treadmill by 1 m/min every min and determined the maximum speed that the mice could run until exhaustion.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Analysis of Total Body Fat

A fed PEPCK-Cmus mouse and two control animals were imaged using a 7T/30-cm Bruker BioSpin small animal magnetic resonance scanner. A multislice, multiecho spin echo acquisition was used to obtain high resolution coronal images of a whole mouse using a 120-mm rat volume coil to transmit and receive, with T1-weighting and respiratory gating (time to repetition/ echo time = 900/9 ms, 512 × 256 matrix, 110 × 41 mm field of view, 33 slices). To separate visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments, the internal cavity within the abdominal wall was manually segmented using a common software package (Analyze 6.0, Mayo Clinic, Minneapolis, MN). Fat was hyper-intense in these images, allowing us to segment adipose tissue by interactively setting a threshold value. Visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue volumes were computed from the number of voxels times the volume of a single voxel. Similar single-slice images were acquired for publication (rapid acquisition with retocussed echoes, TR/TE = 1000/12 ms, 512 × 512 matrix, 100 × 60 mm FOV). Image acquisitions were repeated over 3 weeks to examine measurement repeatability.

Histological and Electron Microscopy Analysis of Tissues

Skeletal muscle was isolated from overnight fasted PEPCK-Cmus and control mice and fixed immediately in formalin solution (Sigma), in liquid N2, or in Tissue-Tek® OTC compound (Sakura Finetek Inc) for staining by hematoxylin and eosin, for succinate dehydrogenase and NADH dehydrogenase, or for electron microscopy, respectively. The histochemical and electron microscopy analysis was performed at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine by the Cytology Laboratory and the Electron Microscopy Facility.

Effect of Aging on the Capacity of PEPCK-Cmus Mice to Run

PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls were maintained in single cages until they reached 24–27 months of age, at which time they were tested for their maximal running speed.

RESULTS

The Generation of PEPCK-Cmus Mice

Six founder lines of transgenic mice were generated using standard DNA microinjection techniques. The chimeric gene introduced into the mice contained a 2-kb segment of the α-skeletal actin gene promoter (9), linked to the 1976-bp cDNA for PEPCK-C from the mouse followed by the 3′ end of the bGH gene (Fig. 1A). The pattern of incorporation of the chimeric gene DNA into the genome of the four founder lines is shown in Fig. 1B. Each of these founder mice expressed the chimeric gene at varying levels, as determined by the level of PEPCK-C enzyme activity and specific mRNA (Fig. 1, C and D). To enhance the effect of PEPCK-C activity on the metabolism of the muscle, we created a new line of mice by breeding founder lines C and D together (Fig. 1C). This breeding produced mice that had varying levels of PEPCK-C activity in their muscles (Fig. 1C); the animals were subsequently used to determine the consequences of overex-pressing PEPCK-C on the metabolism of skeletal muscle. After nine generations of crossbreeding of founder lines C and D, we created a homozygous line of mice, which we termed PEPCK-Cmus mice.

Expression of PEPCK-C in Muscle

The expression of the transgene was assessed by both Northern and Western blotting of several tissues isolated from PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls (Fig. 1, D and E). PEPCK-C mRNA transcribed from the trans-gene was detected in skeletal muscle of PEPCK-Cmus mice; no PEPCK-C mRNA from the transgene was noted in muscle from the control animals. The same pattern was observed by Western blotting, using an antibody specific for PEPCK-C. The level of mRNA for PEPCK-C noted in the skeletal muscle of mice differed in our lines of PEPCK-Cmus mice during the process of breeding founder lines C and D together (Fig. 1D). This was reflected in a variation in the activity of PEPCK-C in the muscle of these mice (Fig. 1C). Homozygous PEPCK-Cmus mice had ∼9 units/g of PEPCK-C activity in gastrocnemius, soleus, and diaphragm; in contrast, the same muscles from control mice have about 0.08 units/g of PEPCK-C activity (Table 1). Since the gene for PEPCK-C was expressed from the α-skeletal actin gene promoter, all the skeletal muscle types determined had the same activity. In addition, the heart from the PEPCK-Cmus mice had 0.74 units/g of enzyme activity; the activity of PEPCK-C is normally undetectable in the hearts of mice. We routinely noted that the activity of PEPCK-C was higher in the livers of the PEPCK-Cmus mice than controls (Table 1). This increased activity was not due to transcription from the transgene since a specific cDNA probe, composed of the 805-bp SmaI-EcoR1 fragment of the bGH gene located at the 3′end of the transgene, did not hybridize to hepatic mRNA (data not shown). The elevated hepatic PEPCK-C activity was most likely due to induced transcription of the endogenous PEPCK-C gene in the liver of the transgenic mice caused by the high level of energy utilization noted in these mice. Subsequent studies of the physiological effect of overexpression of the gene for PEPCK-C in the muscle concentrated on the use of PEPCK-Cmus mice with about 9 units/g of activity of the enzyme in their skeletal muscles.

TABLE 1.

The activity of PEPCK-C in selected tissues

| PEPCK-Cmus | ||

|---|---|---|

| units/g | n | |

| Skeletal muscle | 9.15 ± 1.03 | (4) |

| Soleus | 9.28 ± 1.26 | (4) |

| Gastrocnemius | 8.86 ± 2.04 | (4) |

| Diaphragm | 8.00 ± 1.93 | (4) |

| Heart | 0.74 ± 0.33 | (2) |

| Liver | 5.00 ± 0.33 | (11) |

| Skeletal muscle (WT) | 0.08 ± 0.02 | (8) |

| Liver (WT) | 3.09 ± 0.13 | (6) |

Selected tissues were collected and the activity of PEPCK-C determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The phrase “Skeletal muscle” refers to mixed thigh muscle. The activity of PEPCK-C is expressed as the mean ± S.E. for the number of animals indicated in parentheses. The unit of activity is defined as one µmole of substrate converted to product/min at 37 °C.

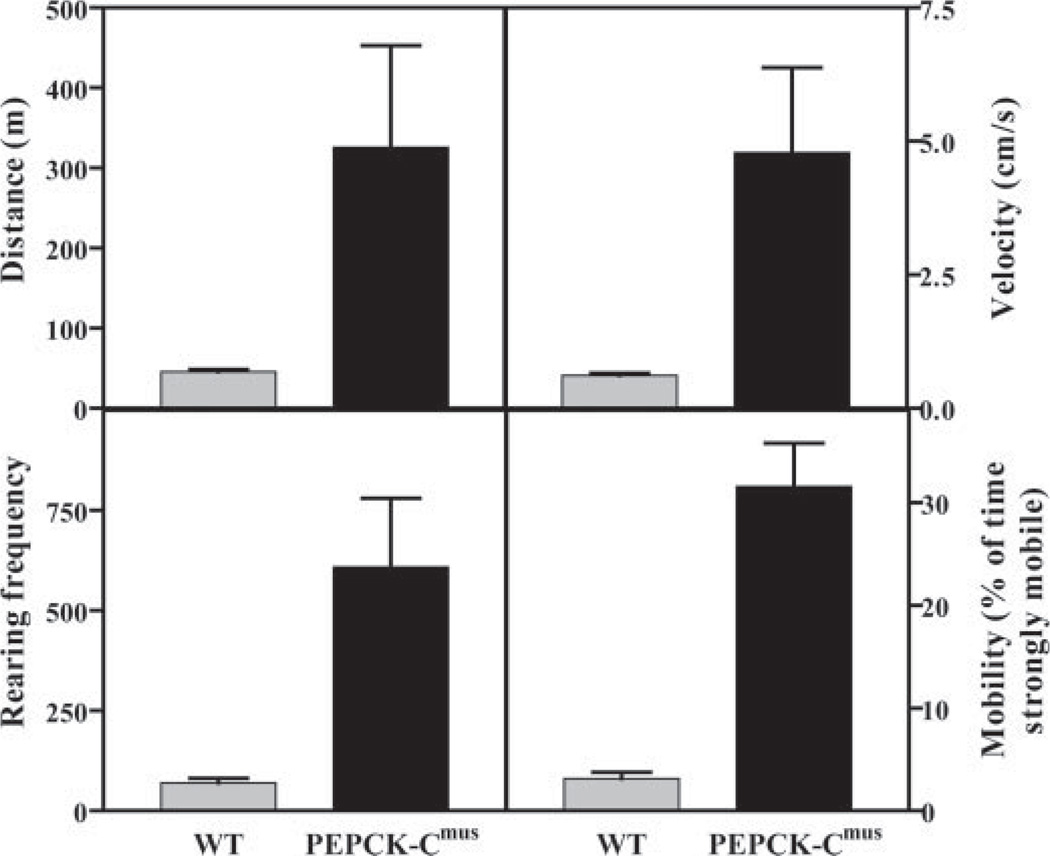

Activity in the Home Cage

During the process of generating a homozygous line of PEPCK-Cmus mice from the C and D founder lines, we noted a very marked increase in the physical activity of the animals as compared with controls; the mice ran continuously in their cages. A systematic analysis of the PEPCK-Cmus mice was thus undertaken. Our preliminary observations did not detect any obvious signs of stereotypy-like locomotion, excessive grooming, or abnormal gait, all of which are potential confounders during home cages activity measurements of the PEPCK-Cmus mice or controls. Turn angle and angular velocities were similar in both groups, thus ruling out spinning (a common example of stereotypy-like locomotion) in the experimental group. Home cage activity measurements indicated that PEPCK-Cmus mice were markedly more active in their home cages as compared with control animals (Fig. 2). This was indicated by a greatly increased distance traveled and an increased rearing frequency. Likewise, PEPCK-Cmus mice had significantly faster movement in the cage as compared with controls (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. The home cage activity of PEPCK-Cmus mice.

The activity of PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls (WT), maintained with a 12-h light/dark cycle, was determined as outlined under “Experimental Procedures.” The measurements made over 22 h included the distance covered, the velocity of the movement, the rearing frequency, and the percentage of time the mice were strongly mobile.

The mobility parameter tracks the location of the pixels, which are identified as belonging to the tracked animal in the current sample frame, and compares them with the pixels in the previous frame. A large difference (more than a user defined threshold) is identified as strongly mobile, a small difference (less than the threshold) is immobile, and values in between are mobile. This allows for a refined and quantifiable categorization of movement, or lack thereof, in experimental subjects. In this regard, our data indicate that although control and PEPCK-Cmus mice spent a similar percentage of time in the mobile range, PEPCK-Cmus mice spent significantly less time immobile and significantly more time as strongly mobile as compared with control mice (Fig. 2). The fact that PEPCK-Cmus mice were faster than controls is in accordance with our strong mobility findings. However, the fact that these animals spent similar portions of time in the mobile range and showed significantly more rearings rules out the possibility that the increased levels of activity (distance traveled) were simply due to a constant higher velocity of the mice.

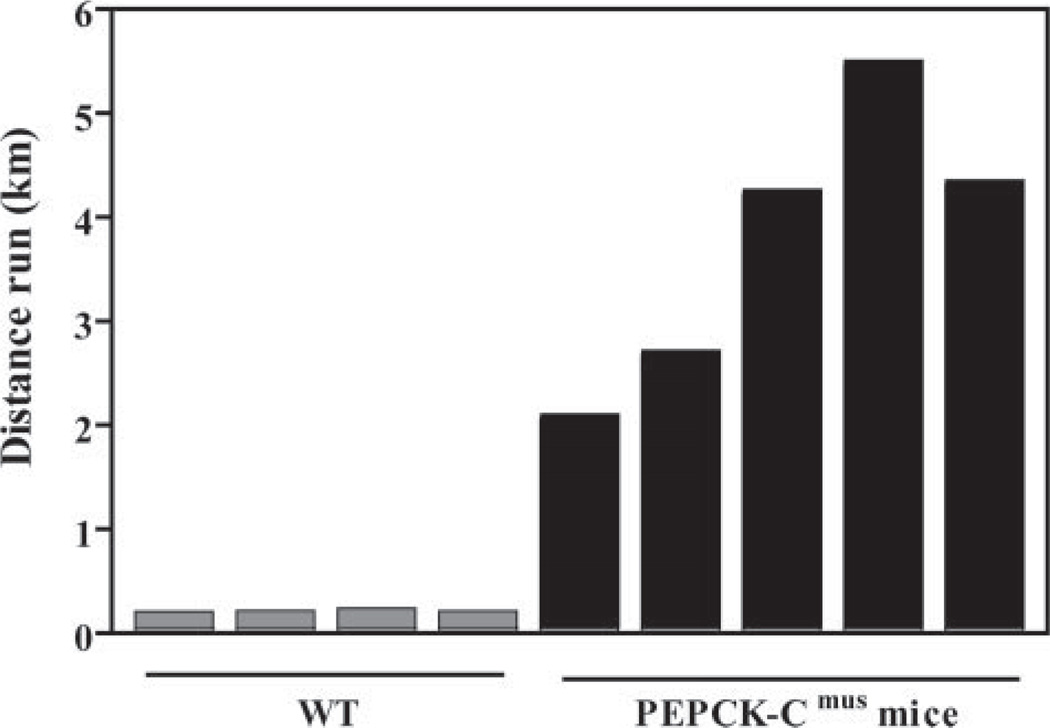

Treadmill Testing

We next tested the ability of PEPCK-Cmus mice to run for distance on a treadmill (Fig. 3). Untrained PEPCK-Cmus mice ran for up to 6 km at a speed of 20 m/min, whereas controls ran for only 0.2 km at the same speed, before exhaustion. The PEPCK-Cmus mice also retained an extraordinary ability to perform strenuous exercise at an age greater than 24 months (see Fig. 9). A sound video of these mice running is included as supplemental data.

FIGURE 3. PEPCK-Cmus mice run for a long distance on a treadmill.

Untrained 3-month-old PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls (WT) were tested for their ability to run long distances. The mice were placed on a treadmill (at a grade of 0°) and run at 20 m/min until exhaustion, as described in the first protocol under “Experimental Procedures.” In the supplemental data, please note that a video is available that documents the remarkable ability of the PEPCK-Cmus mice to run for long distances.

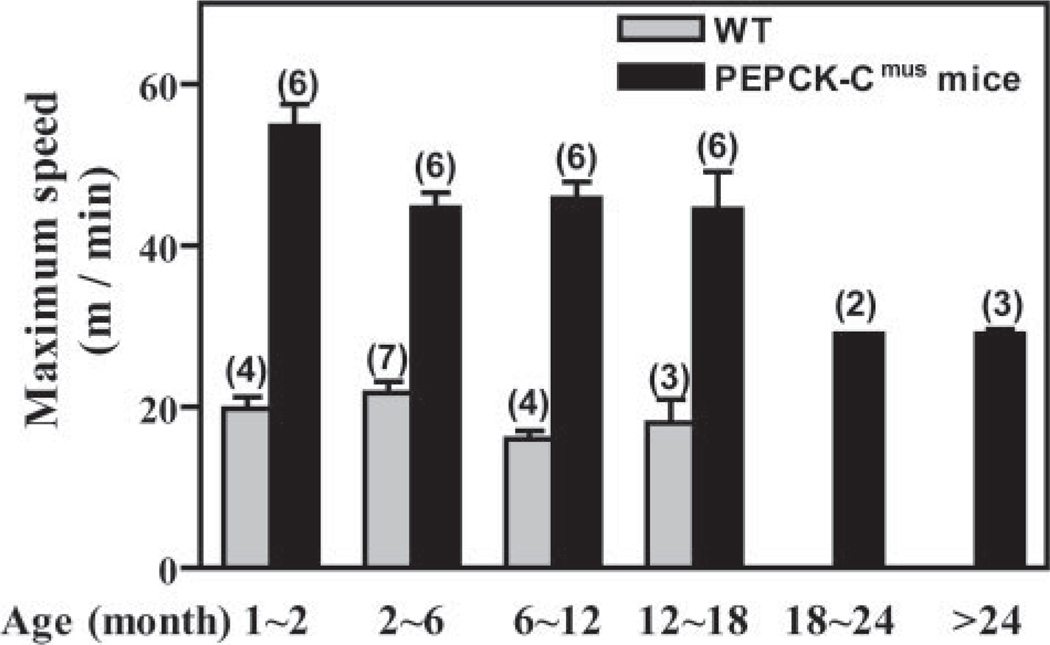

FIGURE 9. Running ability of PEPCK-Cmus mice with age.

Trained PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls (WT) of varying ages were tested for their ability to run on a treadmill using the third protocol as described in detail under “Experimental Procedures.” The mice were acclimated to the treadmill (at a grade of 0°) for 30 min at a speed of 10 m/min, after which time the speed of the treadmill was increased 1 m/min every min, until the mice reached exhaustion. The number of animals tested is indicated in parentheses.

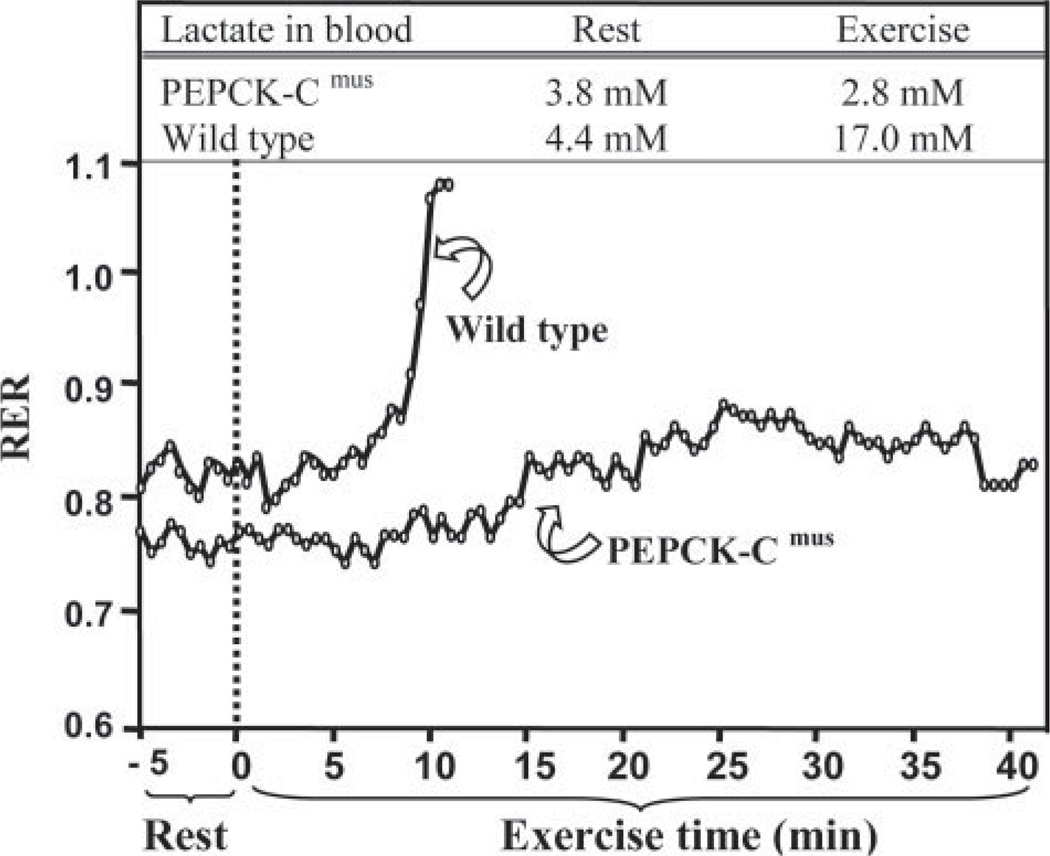

Determining the RER

Oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide generation (both are used to calculate the RER), and alterations in the concentration of lactate in the blood of PEPCK-Cmus and control mice during strenuous exercise were next measured, with animals running on a mouse treadmill using the second exercise protocol that is described in detail under “Experimental Procedures.” After a 60-min period of acclimation, the mice began walking on the treadmill at a speed of 5 m/min at a grade of 0° for a 10-min warm-up. The grade of the treadmill was then set to 25°, and the speed was increased by 2 m/min every 2 min until the mouse reached exhaustion. The resting rate of oxygen consumption of the PEPCK-Cmus mice (n = 9) was 48 ml/kg/ min, as compared with 47 ml/kg/min for controls. The resting blood lactate concentration was 3.7 mm in the PEPCK-Cmus mice and 4.9 mm in controls (Table 2). The PEPCK-Cmus mice ran for a period of 32 min, whereas controls ran for 19 min. The VO2max of the PEPCK-Cmus mice was 156 ml/kg/min as compared with 112 ml/kg/min in control animals. The concentration of lactate in the blood of the PEPCK-Cmus mice was 3.7 mm after maximal exercise, whereas the lactate levels in the control mice reached 8.1 mm. The RER of the PEPCK-Cmus mice was 0.77 during the rest period and increased slowly during exercise to 0.91 at exhaustion (31.9 min of running). In contrast, the control animals (n = 10) began the experiment with an RER of 0.79, which rapidly increased to 0.99 at exhaustion (19 min of strenuous exercise).

TABLE 2.

Metabolic parameters of PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls after strenuous exercise

| Variables | Wild type | PEPCK-Cmus |

|---|---|---|

| n = 10 | n = 9 | |

| VO2 at rest (ml.kg−1.min−1) | 46.9 ± 9.6 | 47.7 ± 10.9 |

| VCO2 at rest (ml.kg−1.min−1) | 37.3 ± 9.34 | 40.9 ± 14.1 |

| RER (VCO2/VO2) at rest | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 0.77 ± 0.05 |

| Blood lactate at rest (mm) | 4.90 ± 0.34 | 3.70 ± 0.17 |

| VO2max (ml.kg−1.min−1) | 112.3 ± 20.9 | 156.4 ± 8.06* |

| VCO2 at VO2max (ml.kg−1.min−1) | 110.8 ± 21.0 | 142.0 ± 8.48* |

| RER at VO2max | 0.99 ± 0.08 | 0.91 ± 0.03* |

| Blood lactate (mm) after exercise | 8.12 ± 5.0 | 3.70 ± 1.00* |

| Maximum speed, (m/min, at 25° slope) | 23.4 ± 4.79 | 36.6 ± 7.60* |

| Maximum running time, (min) | 19.2 ± 4.76 | 31.9 ± 7.63* |

Values are the means ± S.D., for the number of mice shown in the parenthesis. The VO2 (oxygen consumption), VO2max (maximal VO2), VCO2 (carbon dioxide production), VCO2max (maximal CO2 production), and RER were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

p < 0.05.

Fig. 4 is a graphical representation of the difference between a selected PEPCK-Cmus mouse and a control animal that illustrates the extraordinary metabolic characteristics of the PEPCK-Cmus mice. This animal ran for 43 min until exhaustion, as compared with 13 min by its control littermate, and it had an RER of 0.82 at exhaustion (the control animal had an RER of 1.07). What is especially dramatic is the difference in the concentration of lactate in the blood. Although both the PEPCK-Cmus mouse and the control began the period of exercise with nearly equal values of blood lactate concentration, at exhaustion, the concentration of lactate in the blood of the control animal rose to 17 mm, whereas the lactate in the blood of the PEPCK-Cmus mouse remained at the same low level noted before exercise. We conclude that the PEPCK-Cmus mice rely heavily on fatty acids as a source of energy for their muscles during exercise and thus do not generate lactate during this period, despite the strenuous nature of the exercise. The control mice rapidly move from fatty acid metabolism to the utilization of muscle glycogen as a fuel; this results in a marked rise in the concentration of lactate in the blood of these animals.

FIGURE 4. A graphical plot of fuel utilization by a PEPCK-Cmus and control mouse during strenuous exercise.

This figure is a graphical plot of the alterations in the RER of an untrained PEPCK-Cmus mouse and a control animal. The data are drawn from a larger group of PEPCK-Cmus mice (n= 9) and control littermates (n= 10) that is presented in Table 3. The RER was assessed using a speed-ramped treadmill entirely enclosed in an environmental chamber and equipped to measure changes in oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide output. The mice were acclimated to the chamber for 60 min, after which the speed of the treadmill (set at a 25° slope) was set at 10 m/min and for 30 min and then increased 2 m/min every 2 min until the mice reached exhaustion (see the second protocol described under “Experimental Procedures”). A blood sample was taken before and after exercise for the measurement of lactate. Both the rate of oxygen consumption and the rate of carbon dioxide generation by the mice were monitored continuously throughout the exercise period.

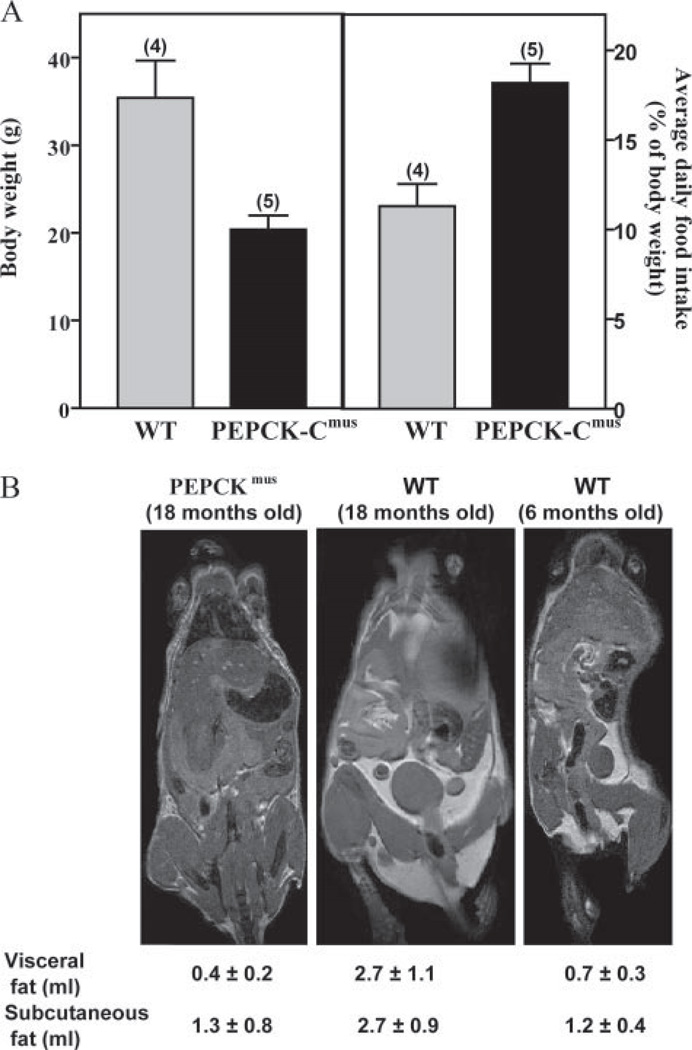

Food Intake and Body Composition of the PEPCK-Cmus Mice

The body weight of both PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls was determined and related to the average daily food intake of the animals (Fig. 5A). The three PEPCK-Cmus mice tested ate, on a body weight basis, an average of 60% more food than controls. Despite eating more, 18-month old PEPCK-Cmus mice weighed less and had dramatically less body fat, as determined by magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 5B). The adipose tissue volumes were 0.4 ± 0.2 ml for visceral depots and 1.3 ± 0.8 ml for subcutaneous. This compares with 0.7 ± 0.3 for visceral depots and 1.2 ± 0.4 for subcutaneous adipose tissue for a 6-month-old control mouse. A control mouse of similar age and genetic background has 2–3 times as much visceral and subcutaneous fat as the PEPCK-Cmus mouse (2.7 ± 1.1 and 2.7 ± 0.9 respectively). Standard error indicates the variability obtained from imaging these same mice weekly over a 3-week period.

FIGURE 5. Food intake and relative body fat of PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls.

A, The average daily food consumption (right panel), as related to the body weight of the mice, was calculated for five control (WT) and 17 PEPCK-Cmus mice daily over a 3-week period. The body weight (left) of the same mice was determined three times a week over a 3-week period. The values are presented as the mean ± S.E. of the mean. B, magnetic resonance imaging showing hyper-intense adipose tissue due to T1-weighting. Animals are an 18-month-old PEPCK-Cmusmouse(CD18), an 18-month-old control (WT), and a 6-month-old control (WT). Volumes of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues were calculated as outlined under “Experimental Procedures.”

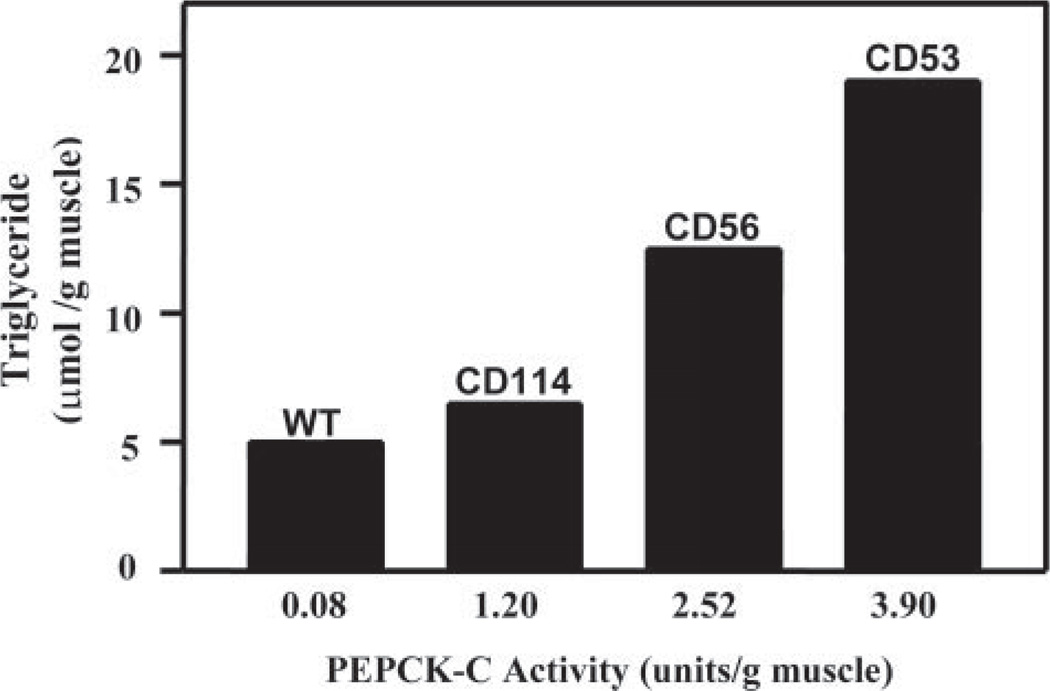

The Relationship between Triglyceride Content of the Muscle and PEPCK-C Activity in PEPCK-Cmus Mice

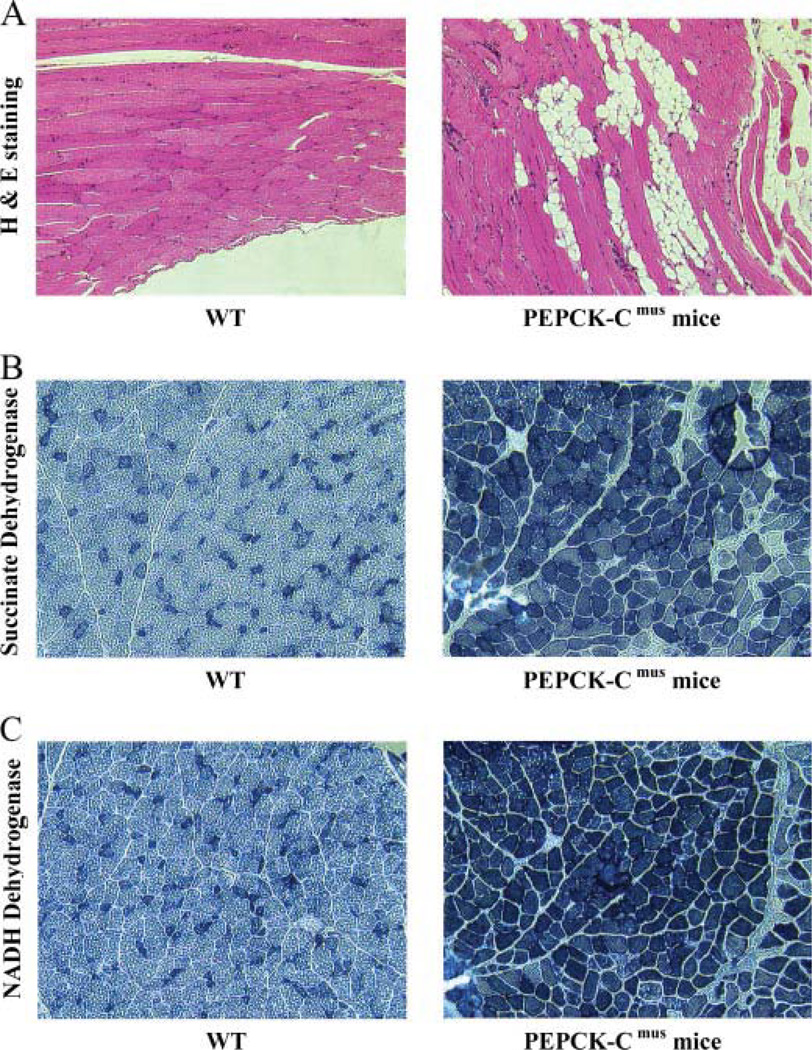

Mice with varying levels of PEPCK-C activity were selected for analysis. These animals were generated from individual mice from the C and D founder lines. The activity of PEPCK-C in the muscle of these animals was 0.08 units/g in a control and 1.20, 2.52, and 3.90 units/g of muscle in the various PEPCK-Cmus mice (Fig. 6). The concentration of triglyceride in the muscle of the animals correlates well with the activity of PEPCK-C determined in the skeletal muscle. The observed relationship between the level of PEPCK-C in the muscle and the concentration of triglyceride is likely due to an increase in the rate of glyceroneogenesis in the tissue, although this remains to be determined experimentally. In agreement with the biochemical measurements, skeletal muscle from PEPCK-Cmus mice, analyzed by hematoxylin and eosin staining (H & E staining), had high concentrations of lipid as compared with controls (Fig. 7A). It seems likely that this high concentration of triglyceride in the skeletal muscle of the PEPCK-Cmus mice provides the fuel needed to sustain their extraordinary level of activity.

FIGURE 6. The relationship between the concentration of triglyceride and the activity of PEPCK-C in the skeletal muscle of PEPCK-Cmus mice and control (WT) animals.

The activity of PEPCK-C and the concentration of triglyceride in skeletal muscle were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The unit of activity is 1 µmol of substrate converted to product per min at 37 °C.

FIGURE 7. Histological analysis of skeletal muscle from PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls.

A, hematoxylin and eosin staining (H & E staining) of skeletal muscle showing lipid inclusions in the muscle of the PEPCK-Cmus mice. B, succinate dehydrogenase staining. C, NADH dehydrogenase staining. All slides are at X200 magnification.

Metabolites in the Blood of PEPCK-Cmus Mice

The concentration of a number of metabolites as well as the activity of creatine kinase was determined in the blood of fed and fasted PEPCK-Cmus and control mice (Table 3). The most striking difference was the greatly increased activity of creatine kinase in the blood of fasted PEPCK-Cmus mice; the activity of this enzyme in the blood of these animals was almost four times that of controls. There were also lower levels of cholesterol, free fatty acids, and triglyceride in the blood of fed PEPCK-Cmus mice. The concentration of glucose in the blood of fed PEPCK-Cmus mice was increased over the values noted in control mice.

TABLE 3.

The concentration of metabolites in blood

| Fed |

Fasted |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | PEPCK-Cmus | p value | Wild type | PEPCK-Cmus | p value | |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 105.6 ± 12.7 (5) | 65.8 ± 10.2 (9) | 0.03a | 83.3 ± 8.2 (6) | 60.2 ± 8.7 (6) | 0.08 |

| Free fatty acid (mEq/liter) | 0.56 ± 0.09 (7) | 0.39 ± 0.06 (10) | 0.10 | 0.62 ± 0.23 (6) | 0.50 ± 0.10 (6) | 0.66 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 95.7 ± 17.7 (7) | 58.7 ± 7.5 (10) | 0.05a | 64.6 ± 22.3 (7) | 48.3 ± 8.0 (6) | 0.53 |

| Ketone bodies (mg/dl) | 1.91 ± 0.23 (7) | 2.82 ± 0.77 (10) | 0.35 | 6.2 ± 1.2 (6) | 6.3 ± 2.0 (6) | 0.96 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 150.7 ± 8.1 (3) | 217.7 ± 6.6 (3) | <0.01a | 119.0 ± 7.3 (5) | 136.4 ± 5.0 (9) | 0.09 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | 29.3 ±2.9 (7) | 29.1 ± 1.8 (10) | 0.95 | 21.8 ± 4.6 (5) | 27.0 ± 2.8 (5) | 0.36 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.11 ± 0.02 (7) | 0.16 ± 0.03 (10) | 0.22 | 0.12 ± 0.02 (5) | 0.13 ± 0.02 (6) | 0.66 |

| Creatine kinase (unit/liter) | 276.2 ± 108.5 (6) | 324.8 ± 69.0 (10) | 0.70 | 121.5 ± 13.1 (6) | 446.0 ± 130.2 (5) | 0.02a |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.27 ± 0.12 (7) | 0.11 ± 0.01 (10) | 0.13 | 0.76 ± 0.38 (5) | 0.10 ± 0.00 (2) | 0.35 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | 4.86 ± 0.20 (7) | 4.60 ± 0.07 (10) | 0.18 | 4.76 ± 0.14 (5) | 4.33 ± 0.44 (3) | 0.25 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.73 ± 0.11 (7) | 2.93 ± 0.14 (10) | 0.32 | 3.06 ± 0.18 (5) | 2.53 ± 0.26 (3) | 0.14 |

Statistical significance.

PEPCK-Cmus mice and control animals were fed ad libitum or fasted for 18 h, and their blood was collected. The analysis of metabolites was performed by Marshfield Laboratories, as outlined under “Experimental Procedures.” The results are expressed as the means ± S.E. for the number of animals indicated in parentheses. The p value is calculated for PEPCK-Cmus mice and wild type animals.

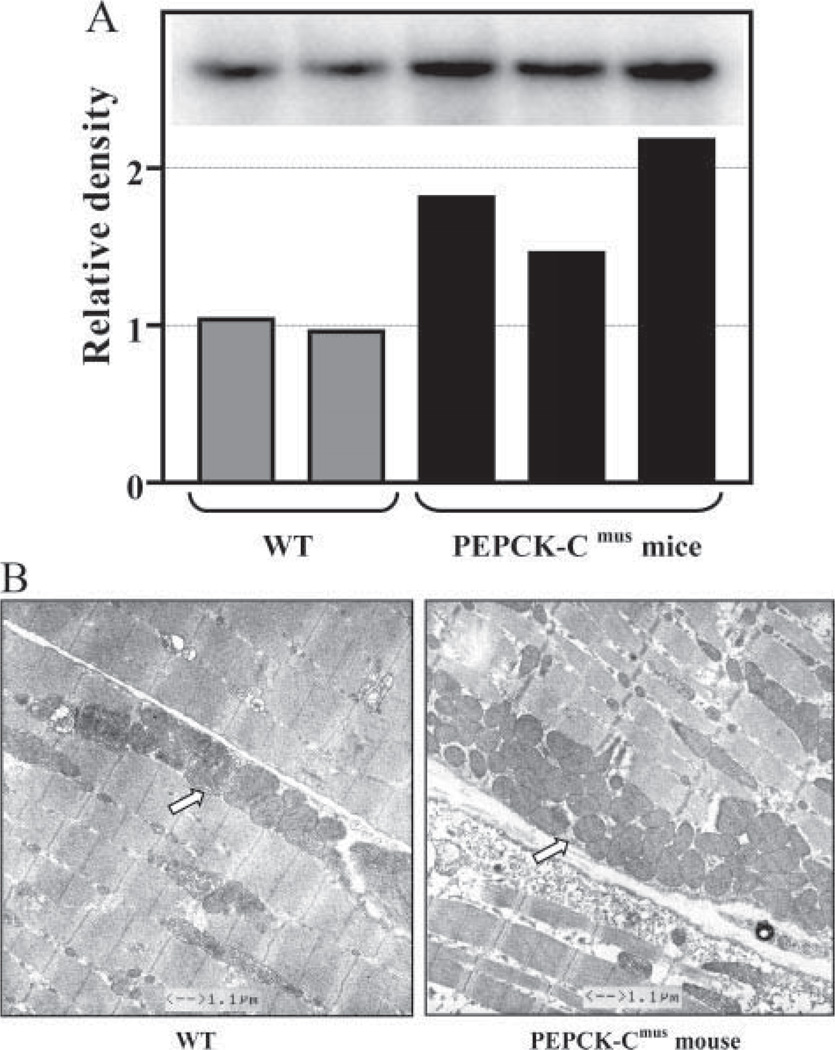

The Muscle of PEPCK-Cmus Mice Contains More Mitochondria

The dramatic difference in fuel utilization during strenuous exercise suggests a profound shift in energy metabolism in the muscle. Histochemical analysis of skeletal muscle from PEPCK-Cmus mice and a control animal indicated a marked increase in the activity of succinate dehydrogenase and NADH dehydrogenase (Fig. 7, B and C). These results are consistent with a greater number of mitochondria in the skeletal muscle. This is supported by the increased mitochondrial DNA in skeletal muscle from three PEPCK-Cmus mice, as compared with control animals (Fig. 8A). The electron microscopy image shown in Fig. 8B demonstrates a marked increase in mitochondria in the soleus muscle of the PEPCK-Cmus mice relative to controls.

FIGURE 8. Increased mitochondrial content in skeletal muscle of PEPCK-Cmus mice.

A, the relative concentration of mitochondrial DNA in skeletal muscle of PEPCK-Cmus mice and controls (WT). The inset is a Southern blot of DNA isolated from three PEPCK-Cmus mice and two control animals. B, electron micrographs of soleus muscle from PEPCK-Cmus mouse and a control animal (WT) showing an increased number of mitochondria (arrow).

Aging of the PEPCK-Cmus Mice

We noted that the PEPCK-Cmus mice survived far longer and looked healthier than controls and that both male and female PEPCK-Cmus mice were reproductively active at 21 months of age; one PEPCK-Cmus mouse gave birth at 30 months of age (data not shown). We therefore tested the running ability of PEPCK-Cmus and control mice at various ages using the third protocol described in detail under “Experimental Procedures.” The mice were given a period of 30 min acclimation to the treadmill followed by a 30-min warm-up period in which they were run at a speed of 10 m/min with no elevation of the treadmill. The speed of the treadmill was increased by 1 m/min every min until the mice were exhausted (Fig. 9). At all ages tested, the PEPCK-Cmus mice performed significantly better than control animals. Twelve-to 18-month-old PEPCK-Cmus mice ran at an average maximum speed of 45 m/min, as compared with 22 m/min for 6-month-old control mice. PEPCK-Cmus mice from 18 months of age to older than 24 months also ran at a higher rate of speed than control animals that were 2- 6 months of age.

DISCUSSION

The α-skeletal actin gene promoter has been widely used for the expression of genes specifically in skeletal muscle of transgenic mice (9, 10, 17). The gene promoter (from −2000 to + 239) drives a high level of expression in all types of striated muscle and is regulated in a tissue-specific manner during development (9). Transcription from the α-skeletal actin gene promoter in the mouse hind limb is initiated at about embryonic day 14, when it replaces α-cardiac actin as the major sar-comeric actin. Clapham et al. (10) used the mouse α-skeletal actin gene promoter to drive the expression of the structural gene for uncoupling protein-3 (UCP-3) in the skeletal muscle of transgenic mice. They reported expression of the UCP-3 trans-gene in skeletal muscle, with a small (5%) fraction of the activity also noted in brown adipose tissue. There was no UCP-3 mRNA, as determined by reverse transcription-PCR, in 12 other tissues from their mice. We also noted expression of the gene for PEPCK-C mainly in skeletal muscle of our transgenic mice. PEPCK-C mRNA was not detected by Northern blotting in the hearts of any of the four founder lines measured but was noted in mice generated after crossing founder lines C and D (PEPCK-Cmus mice). We assume that transcription from the α-skeletal actin gene promoter occurred in the hearts of the PEPCK-Cmus mice due to cardiac hypertrophy induced in the PEPCK-Cmus mice by their marked hyperactivity. The effect that the expression of the gene for PEPCK-C has on cardiac function remains to be determined. However, it is likely that the majority of the metabolic and behavioral changes noted in the PEPCK-Cmus mice are due to metabolic alterations resulting from the overexpression of PEPCK-C in skeletal muscle and that the presence of PEPCK-C in the heart is an adaptation to the greatly increased physical activity that characterize these mice.

It is remarkable that the overexpression of a single enzyme involved in a metabolic pathway should result in such a profound alteration in the phenotype of the mouse. There are several recent examples of marked alterations in energy metabolism in transgenic mice; these involve PPARδ, a transcription factor (17) or PGC-1α (18) or PGC-1β (19), transcriptional co-regulators. The overexpression of the genes for these proteins would be expected to alter expression of a number of genes in the muscle. The gene for PPARδ was driven by the α-skeletal actin gene promoter, and the transgene was expressed in skeletal muscle (17). These mice had increased type 1 muscle fibers and demonstrated an enhanced exercise performance. The genes for PGC-1α and PGC-1β were transcribed in transgenic mice from the muscle creatine kinase gene promoter and resulted in an increase in type 1 muscle fibers (PGC-1α) (18) and an increase in type II fibers (PGC-1β) (19) in the skeletal muscle of the animals. Mice that overexpress PPARδ ran for 1.5 km before exhaustion (17), as compared with the 5-6 km noted with the PEPCK-Cmus mice (Fig. 3).

One of the most notable physiological differences caused by the overexpression of PEPCK-C was the 40% increase in VO2max in these animals as compared with controls. This level of oxidative capacity is comparable with data reported for trained mice that were selectively bred through 10 generations to produce mice with outstanding running ability (20). The elevated oxidative capacity in the PEPCK-Cmus mice cannot be attributed to exercise training per se but was likely due to the high daily activity levels of these mice and the genetic manipulation, which, when combined, led to the dramatic increase in mitochondrial biogenesis noted in skeletal muscle and the greatly increased concentration of triglyceride in the muscle. These cellular changes most likely had the effect of enhancing the oxidative capacity of the muscle during exercise and providing additional fuel to support energy metabolism. In this regard, the PEPCK-Cmus mice did not accumulate lactate in their blood during maximal exercise and were able to use fatty acids as an energy source during intensive exercise. They had an RER of 0.91 and a VO2max of 156 ml/kg/min at exhaustion (i.e. after 37 min of running at an increasing speed on a treadmill set at a 25° incline). Over this entire period of strenuous exercise, the PEPCK-Cmus mice generated no net lactate; control animals had a blood lactate concentration of 8.12 mm. The increase in oxidative capacity of the muscle of the PEPCK-Cmus mice is most likely supported by more complete oxidation of glucose/ glycogen and the high concentration of triglyceride noted in the muscles (up to 10 times that of control animals).

It is well known that endurance training results in an increased glycogen store and an elevated utilization of fatty acids relative to carbohydrate by skeletal muscle. However, fed PEPCK-Cmus mice have slightly lower glycogen stores (1.3 ± 0.1 versus 1.7 ± 0.3 mg/g of tissue, p = 0.2) but greater levels of triglyceride in their skeletal muscle than controls and use fatty acids extensively during prolonged exercise. Dohm et al. (21) reported that rats running at a speed of 28 m/min did not accumulate either lactate or pyruvate in their blood, presumably because low intensity exercise can be accomplished via aerobic metabolism. The aerobic metabolism of lactate and pyruvate requires pyruvate decarboxylation via the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex to acetyl CoA, which is subsequently oxidized in the citric acid cycle. They reported that rats running at a speed of 28 m/min for 30 min had a 2-fold increase in both PEPCK-C and pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in their skeletal muscles; the activity of both enzymes decreased markedly within 5 min after the cessation of exercise. Since there are no known allosteric regulators of PEPCK-C in any tissue, the factors that are responsible for the rapid alterations in its activity in skeletal muscle are not clear. However, the effect was dramatic enough to suggest that alterations in the activity of PEPCK-C could be an important factor in the response of the animal to exercise. This is supported by the observation that the concentration of P-enolpyruvate in the skeletal muscle is reduced by 50% after 30 min of exercise (21).

How Does Overexpressing PEPCK-C Alter Energy Metabolism in Skeletal Muscle?

PEPCK-Cmus mice have a high level of physical activity, supported in part by larger triglyceride reserves in their skeletal muscle, more complete oxidation of carbohydrate as evidenced by attenuated lactate production in response to exercise, more mitochondria, and enhanced food intake. The increased activity of the PEPCK-Cmus mice is spontaneous; it was evident as early as 2 weeks after birth. It is not clear, however, how an overexpression of a single enzyme can so drastically repattern energy metabolism in the mice. There are several previously suggested mechanisms, which could partly account for the profound changes in energy metabolism.

First, the increase in physical activity requires ATP to drive muscle contraction. This ATP is produced by an increased flux of intermediates through the citric acid cycle. Since PEPCK-C uses GTP and generates GDP and succinyl CoA synthase requires GDP, a possible link exists between PEPCK-C and citric acid cycle activity. Some years ago, Hahn and Novak (22) noted that brown adipose tissue had four times the PEPCK-C activity found in white adipose tissue (based on cellular protein content) and suggested that the “extra” PEPCK-C activity is involved in a cycle in which the enzyme uses the GTP generated in the citric acid cycle by succinyl CoA synthase to form P-enol-pyruvate from oxalacetate, which is converted to pyruvate by pyruvate kinase. Pyruvate can then be decarboxylated to acetyl CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and used to generate energy in the citric acid cycle. Since PEPCK-C is in the cytosol, this scheme would require the movement of guanine nucleotides across the inner mitochondrial membrane or the conversion of GTP to ATP by nucleoside diphosphokinase in the mitochondria and its subsequent transport and conversion back to GTP. The intracellular location of the different isoforms of this enzyme in muscle is not clear, although studies suggest that hepatic nucleoside diphosphokinase is present outside the mitochondrial matrix. There is also evidence that GTP may be transported directly from the mitochondrial matrix on an atractyloside-insensitive carrier, but the rate of transport via this carrier is slower than the well characterized ATP/ADP translocase (23). However, the requirement for guanine nucleotides in non-dividing tissues is low, so that the transport process may be sufficient to meet the physiological requirements for guanine nucleotides in tissues such as skeletal muscle. If such a cycle exists in mammalian skeletal muscle, the overexpression of PEPCK-C could greatly enhance the rate of citric acid cycle flux and contribute to the generation of ATP required to support the increased physical activity noted with the PEPCK-Cmus mice.

Second, PEPCK-C could be involved in either cataplerosis or anaplerosis. Cataplerosis is the removal of citric acid cycle anions that accumulate when the carbon skeletons of amino acids enter the cycle for ultimate degradation (7). This process is especially important in muscle, where exercise and protein turnover generates considerable amino acid flux, with subsequent oxidation (24, 25). In addition, metabolic processes such as hepatic and renal gluconeogenesis and glyceroneogenesis are fundamentally cataplerotic since they involve the removal of citric acid cycle anions for biosynthesis. Viewed in this way, it is not surprising that normal skeletal muscle would have some PEPCK-C activity. Newsholme and Williams (26) reported 0.37 and 0.26 units/g of PEPCK-C activity in quadriceps and diaphragm of the rat; this activity was induced 8-fold in the quadriceps after 72 h of starvation.

The synthesis of alanine from pyruvate in skeletal muscle is another example of a cataplerotic process. Snell and Duff (27) demonstrated that glutamate and valine stimulated the release of alanine by rat diaphragm and that this stimulation could be blocked by the addition of 3-mercaptopicolinate, an inhibitor of PEPCK-C (28). They proposed that PEPCK-C converted the oxalacetate, which was generated in the citric acid cycle from the metabolism of glutamate and valine, to P-enolpyruvate, which was subsequently converted to pyruvate via M-type pyruvate kinase and then transaminated to alanine by alanine aminotransferase. However, we could not detect an increase in the concentration of alanine in the blood or muscle of the PEPCK-Cmus mice as compared with control mice (data not shown).

Cataplerosis may also be important during or after strenuous exercise when the concentration of citric acid cycle intermediates in the mitochondria of skeletal muscle greatly increases. There is a rapid, 10-fold increase in the concentration of intermediates of the citric acid cycle (anaplerosis) in muscle at the onset of moderate to intense exercise, which declines with strenuous exercise (24). It has been hypothesized that the rate of citric acid cycle flux, and thus ATP generation via the respiratory chain, might be limited by the concentration of intermediates in the cycle (24, 25, 29, 30); the presence of PEPCK-C in muscle may provide a mechanism for the removal of citric acid cycle intermediates during or after exercise. In this regard, ablation of PEPCK-C activity in the liver greatly decreased citric acid cycle flux (8, 31), so that it is likely that an increase in the activity of the enzyme would have the opposite effect.

Of course, it is possible that PEPCK-C overexpression results in anaplerosis. PEPCK-C is a reversible enzyme in vitro (it has an Keq of 0.37 m at 30 °C) so that one could speculate that the reaction generates oxalacetate from P-enolpyruvate to replenish the citric acid cycle in vivo. This would also produce GDP, which could stimulate the activity of succinyl CoA synthase and enhance citric acid cycle flux. However, many tissues contain substantial activity of pyruvate carboxylase, the major anaplerotic enzyme, which generates oxalacetate directly in the mitochondria.

A third possible role of PEPCK-C in skeletal muscle is glyceroneogenesis. Skeletal muscle synthesizes and deposits considerable triglyceride to support energy metabolism. We have demonstrated that glyceroneogenesis, not glycolysis, is the major source of the glyceride-glycerol found in triglyceride in the soleus and gastrocnemius muscle of the rat.3 Surprisingly, even when rats are fed a diet high in carbohydrate, the glyceride-glycerol isolated from the triglyceride in these muscles is derived from glyceroneogenesis and not from glycolysis. Thus, PEPCK-C, the key step in glyceroneogenesis, is most likely involved in triglyceride-fatty acid cycling in skeletal muscle (32). We also assume that overexpression of PEPCK-C in skeletal muscle of the PEPCK-Cmus mice causes the deposition of the observed triglyceride by providing the 3-phosphoglycerol required for its synthesis. We plan to determine the rate of glyceroneogenesis in the skeletal muscle of these mice to directly assess this possibility.

Mitochondrial Biogenesis in PEPCK-Cmus Mice

Our studies clearly demonstrate that skeletal muscle of adult PEPCK-Cmus mice have more mitochondria than control animals of the same age. We have not determined the developmental pattern of mitochondrial biogenesis but assume that this occurs early in life since we noted that PEPCK-Cmus mice are highly active within the first 2 weeks after birth. It has been well established that contractile activity, such as endurance exercise, results in mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle and the development of type I muscle fibers (33). In addition, feeding mice a high fat diet and giving heparin to increase the concentration of free fatty acid in the blood induced mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle (34). This is due in part to an up-regulation of PPARγ (35), PPARα (36), and PGC-1α (37), which interact to promote the oxidative capacity of skeletal muscle by stimulating the transcription of genes that lead to mitochondrial biogenesis (see Ref. 33 for a review). PPARα, PPARγ, and PGC-1α act upstream of several genes that code for the transcription factors NRF-1, NRF-2a, and Tfam, which themselves induce mitochondrial biogenesis. Wu et al. (38) reported that transducer of regulated CREB-binding proteins, a co-activator of CREB, can induce PGC-1α gene transcription and induce mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle cells. Transducer of regulated CREB-binding proteins has also been shown to function as a calcium- and cAMP-sensitive mediator that coordinates the effects of the two pathways on gene transcription (39). This links the calcium, which is released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in response to contractile activity, with the activation of the transcriptional process that induces mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle. Exercise stimulates PGC-1α by activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway via calcium signaling through the calcineurin/myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) signaling cascade (40). Calcium may also exert a positive regulatory effect on PGC-1α gene transcription via the CRE site on the gene promoter, by activating the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase pathway (41, 42). Finally, strenuous exercise depletes ATP in skeletal muscle and increases the concentration of AMP via adenylate kinase; the result is an activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. A number of recent studies have shown that AMP-activated protein kinase is necessary for mitochondrial biogenesis via an induction of the PGC-1α-NRF pathway (43–45). Taken together, the current information on the mechanisms responsible for mitochondrial biogenesis supports an energy-driven stimulus (perhaps related to increased fatty acid availability), such as that which occurs in the skeletal muscle of the PEPCK-Cmus mice as the initiating factor. Increased physical activity caused by an enhanced rate of citric acid cycle flux could be a critical point in the repatterning of energy metabolism noted in these mice.

Blood Metabolites in the PEPCK-Cmus Mice

An elevated activity of creatine kinase in the blood is a widely used marker of skeletal muscle damage. It is commonly observed after intense or extreme exercise (46, 47). The elevated resting creatine kinase levels in the PEPCK-Cmus mice may be indicative of muscle damage due to the continuous, repeated stress caused by high levels of activity. One of us (48) previously reported that exercise-induced muscle damage is associated with increased circulating creatine kinase and insulin resistance. The elevated glucose response to feeding in the PEPCK-Cmus mice supports the possibility that, despite being lean and highly active, these mice may be insulin-resistant. A more detailed evaluation to follow up on these observations is ongoing. Alternatively, the elevated creatine kinase may be reflective of apoptosis and accelerated muscle remodeling that are a normal part of exercise-induced adaptations in skeletal muscle (49).

Aging of the PEPCK-Cmus Mice

It is well established that caloric restriction leads to increased life span in species ranging from yeast (50) to rodents (51) and increases mitochondrial biogenesis in human skeletal muscle (52); this may be due to an up-regulation of SIRT1, which activates transcription of the gene for PGC-1α. Although we have not carried out a detailed aging study on our mice, we have noted that PEPCK-Cmus mice live longer and are more energetic at an older age than are control animals (Fig. 9), despite having a greater daily food intake. Holloszy (53) reported that female rats given access to voluntary running wheels had improved survival. These rats had an increase in food intake that accompanied the increase in exercise. We have also noted that 30-month-old female PEPCK-Cmus mice gave birth to normal sized litters. A more detailed analysis of this phenomenon, with more mice, will be required to conclusively support this preliminary observation. Finally, a major question, which is unanswered by the present study, is what alterations occur in the brains of the PEPCK-Cmus mice that cause the behavior described in detail in this report.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Brian Hoit for generously allowing us to use the mouse treadmill, Nancy Edgehouse for the histological analysis, and Dr. Hisashi Fujioka for the electron microscopy of the muscle. We also appreciate the help of Xiaoying Kong and Tertius Tuy in this study.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK058620 and DK025541 (to R. W. H.), GM-66309 (to M. E.C.), AG12834 (to J. P. K.), EB004070 (to D. L W.), and CA43703 (to the Case Western Reserve University Comprehensive Cancer Center), by a Provost Vision Fund grant to support the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine Behavioral Core Laboratory (to G.C.), by Grant NNJ06HD81G (to M. E. C.) from the NASA, and by an Ohio BRTT, The Biomedical Structure, Functional and Molecular Imaging Enterprise grant. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains a video with sound showing mice performing a treadmill test.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

The abbreviations used are: PEPCK-C, the cytosolic form of phosphoenol- pyruvate carboxykinase (GTP); bGH, bovine growth hormone; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; WT, wild type; CRE, cAMP-response element; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein; P-enolpyruvate, phosphoenolpyruvate.

C. K. Nye, R. W. Hanson, and S. C. Kalhan, unpublished results.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanson RW, Patel YM, editors. P-Enolpyruvate Carboxykinase: the Gene and the Enzyme. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1994. pp. 203–281. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmer DB, Magnuson MA. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1990;38:171–178. doi: 10.1177/38.2.1688895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franckhauser S, Munoz S, Pujol A, Casellas A, Riu E, Otaegui P, Su B, Bosch F. Diabetes. 2002;51:624–630. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olswang Y, Cohen H, Papo O, Cassuto H, Croniger CM, Hakimi P, Tilghman SM, Hanson RW, Reshef L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:625–630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022616299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Opie LH, Newsholme EA. Biochem. J. 1967;103:391–399. doi: 10.1042/bj1030391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crabtree B, Newsholme EA. Biochem. J. 1972;126:49–58. doi: 10.1042/bj1260049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owen OE, Kalhan SC, Hanson RW. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:30409–30412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgess SC, Hausler N, Merritt M, Jeffrey FM, Storey C, Milde A, Koshy S, Lindner J, Magnuson MA, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48941–48949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan KJ, Hardeman EC. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:719–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clapham JC, Arch JR, Chapman H, Haynes A, Lister C, Moore GB, Piercy V, Carter SA, Lehner I, Smith SA, Beeley LJ, Godden RJ, Herrity N, Skehel M, Changani KK, Hockings PD, Reid DG, Squires SM, Hatcher J, Trail B, Latcham J, Rastan S, Harper AJ, Cadenas S, Buckingham JA, Brand MD, Abuin A. Nature. 2000;406:415–418. doi: 10.1038/35019082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGrane MM, deVente J, Yun J, Bloom J, Park EA, Wynshaw-Boris A, Wagner T, Rottman FM, Hanson RW. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:11443–11451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGrane MM, Yun JS, Moorman AFM, Lamers WH, Hendrick GK, Arafah BM, Park EA, Wagner TE, Hanson RW. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:22371–22379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo-Warren H, Cimbala MA, Felz K, Monahan JE, Leis JP, Hanson RW. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:10224–10229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballard FJ, Hanson RW. Biochem. J. 1967;104:866–871. doi: 10.1042/bj1040866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folch J, Lees M, Stanley S. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wieland O. Methods in Enzymatic Analysis. New York: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 211–213. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang YX, Zhang CL, Yu RT, Cho HK, Nelson MC, Bayuga-Ocampo CR, Ham J, Kang H, Evans RM. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin J, Wu H, Tarr PT, Zhang CY, Wu Z, Boss O, Michael LF, Puigserver P, Isotani E, Olson EN, Lowell BB, Bassel-Duby R, Spiegelman BM. Nature. 2002;418:797–801. doi: 10.1038/nature00904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arany Z, Lebrasseur N, Morris C, Smith E, Yang W, Ma Y, Chin S, Spiegelman BM. Cell Metab. 2007;5:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swallow JG, Garland T, Jr, Carter PA, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998;84:69–76. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dohm GL, Patel VK, Kasperek GJ. Biochem. Med. Metab. Biol. 1986;35:260–266. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(86)90081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hahn P, Novak M. J. Lipid Res. 1975;16:79–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKee EE, Bentley AT, Smith RM, Jr, Kraas JR, Ciaccio CE. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;279:C1870–C1879. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.6.C1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sahlin K, Katz A, Broberg S. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;259:C834–C841. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.5.C834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibala MJ, MacLean DA, Graham TE, Saltin B. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1997;502:703–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.703bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newsholme EA, Williams T. Biochem. J. 1978;176:623–626. doi: 10.1042/bj1760623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snell K, Duff DA. Biochem. J. 1977;162:399–403. doi: 10.1042/bj1620399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jomain-Baum M, Schramm VL, Hanson RW. J. Biol. Chem. 1976;251:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aragon JJ, Lowenstein JM. Eur. J. Biochem. 1980;110:371–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SH, Davis EJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:420–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hakimi P, Johnson TM, Yang J, Lepage FD, Conlon AR, Kalhan CS, Reshef L, Tilghman MS, Hanson WR. Nutr. Metab. 2005;2:33. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-2-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reshef L, Olswang Y, Cassuto H, Blum B, Croniger CM, Kalhan SC, Tilghman SM, Hanson RW. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30413–30416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hood DA. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;90:1137–1157. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.3.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Roves P, Huss JM, Han DH, Hancock CR, Iglesias-Gutierrez E, Chen M, Holloszy JO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:10709–10713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704024104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cresci S, Wright LD, Spratt JA, Briggs FN, Kelly DP. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;270:C1413–C1420. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.5.C1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehman JJ, Barger PM, Kovacs A, Saffitz JE, Medeiros DM, Kelly DP. J. Clin. Investig. 2000;106:847–856. doi: 10.1172/JCI10268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC, Spiegelman BM. Cell. 1999;98:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Z, Huang X, Feng Y, Handschin C, Feng Y, Gullicksen PS, Bare O, Labow M, Spiegelman B, Stevenson SC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:14379–14384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606714103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koo SH, Flechner L, Qi L, Zhang X, Screaton RA, Jeffries S, Hedrick S, Xu W, Boussouar F, Brindle P, Takemori H, Mont-miny M. Nature. 2005;437:1109–1111. doi: 10.1038/nature03967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akimoto T, Pohnert SC, Li P, Zhang M, Gumbs C, Rosenberg PB, Williams RS, Yan Z. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:19587–19593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu H, Kanatous SB, Thurmond FA, Gallardo T, Isotani E, Bassel-Duby R, Williams RS. Science. 2002;296:349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.1071163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Handschin C, Rhee J, Lin J, Tarr PT, Spiegelman BM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:7111–7116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232352100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terada S, Goto M, Kato M, Kawanaka K, Shimokawa T, Tabata I. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;296:350–354. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00881-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atherton PJ, Babraj J, Smith K, Singh J, Rennie MJ, Wacker-hage H. FASEB J. 2005;19:786–788. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2179fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reznick RM, Shulman GI. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2006;574:33–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cannon JG, Orencole SF, Fielding RA, Meydani M, Meydani SN, Fiatarone MA, Blumberg JB, Evans WJ. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;259:R1214–R1219. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.6.R1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirwan JP, Clarkson PM, Graves JE, Litchfield PL, Byrnes WC. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1986;55:330–333. doi: 10.1007/BF02343808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirwan JP, Hickner RC, Yarasheski KE, Kohrt WM, Wiethop BV, Holloszy JO. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992;72:2197–2202. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.6.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boffi FM, Cittar J, Balskus G, Muriel M, Desmaras E. Equine Vet. J. 2002;34:275–278. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2002.tb05432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin SJ, Defossez PA, Guarente L. Science. 2000;289:2126–2128. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ingram DK, Anson RM, de Cabo R, Mamczarz J, Zhu M, Mattison J, Lane MA, Roth GS. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1019:412–423. doi: 10.1196/annals.1297.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Civitarese AE, Carling S, Heilbronn LK, Hulver MH, Ukropcova B, Deutsch WA, Smith SR, Ravussin E. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holloszy JO. J. Gerontol. 1993;48:B97–B100. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.3.b97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.