Abstract

Background

Heart failure (HF) is one of the leading causes of hospitalization in adults in Brazil. However, most of the available data is limited to unicenter registries. The BREATHE registry is the first to include a large sample of hospitalized patients with decompensated HF from different regions in Brazil.

Objective

Describe the clinical characteristics, treatment and prognosis of hospitalized patients admitted with acute HF.

Methods

Observational registry study with longitudinal follow-up. The eligibility criteria included patients older than 18 years with a definitive diagnosis of HF, admitted to public or private hospitals. Assessed outcomes included the causes of decompensation, use of medications, care quality indicators, hemodynamic profile and intrahospital events.

Results

A total of 1,263 patients (64±16 years, 60% women) were included from 51 centers from different regions in Brazil. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (70.8%), dyslipidemia (36.7%) and diabetes (34%). Around 40% of the patients had normal left ventricular systolic function and most were admitted with a wet-warm clinical-hemodynamic profile. Vasodilators and intravenous inotropes were used in less than 15% of the studied cohort. Care quality indicators based on hospital discharge recommendations were reached in less than 65% of the patients. Intrahospital mortality affected 12.6% of all patients included.

Conclusion

The BREATHE study demonstrated the high intrahospital mortality of patients admitted with acute HF in Brazil, in addition to the low rate of prescription of drugs based on evidence.

Keywords: Heart Failure/mortality, Epidemiology, Hospitalization, Inappropriate Prescribing

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) has been pointed to as an important public health problem and regarded as a new epidemic with high mortality and morbidity, in spite of the advances in current therapeutics. Updated data from the American Heart Association (AHA) estimated a prevalence of 5.1 million individuals with HF in the United States alone between 2007 and 2012. Projections show that the prevalence of HF will increase 46% between 2012 and 2030, resulting in more than 8 million individuals above the age of 18 years with HF1.The rising prevalence is probably due to the increase in life expectancy, since HF affects predominantly older age groups2.

HF is the leading cause of hospitalization, based on data available from about 50% of the population in South America3.The most comprehensive portrait of the situation of hospitalizations for HF in Brazil can be obtained through analyses of DATA-SUS records, with the inherent limitations of a database of an administrative nature. Data show that in 2012 alone there were 26,694 deaths in Brazil due to HF. Of 1,137,572 admissions due to circulatory diseases in that same year, around 21% were due to HF4.

The burden becomes even more significant when we consider that almost 50% of all hospitalized patients with this diagnosis are readmitted within 90 days after hospital discharge, and that hospital readmission is one of the main risk factors for death in this syndrome5,6.Several studies have focused on identifying the factors associated with frequent readmissions7,8. Those usually described in the international literature are inadequate therapy, lack of adherence to treatment, social isolation, or worsening cardiac function. However, in approximately 30-40% of the cases it is not possible to identify the cause of clinical decompensation9.

Data on morbidity and consequent costs associated with decompensated HF are undeniable all over the world. In Brazil, there are only a few studies comprehensively and prospectively assessing the demographic, clinical and prognostic characteristics of patients who are admitted with a clinical diagnosis of HF. Isolated initiatives suggest the existence of significant regional differences in several characteristics of patients who are admitted with HF in Brazil, but these comparisons are methodologically limited by often divergent guidelines and inclusion criteria10-12.Thus, the establishment of a national registry which incorporates a group of public and private hospitals from different Brazilian regions can portray more accurately which patients are admitted with a diagnosis of HF, how these patients are treated in their institutions and what are their short- and long-term prognoses.

The BREATHE study is the first national and multicenter registry of acute HF that includes all regions of the country, involving 51 public and private hospitals in 21 cities in Brazil. The aim of this analysis is to describe the clinical features, treatment and prognosis of hospitalized patients admitted with acute HF in Brazil.

Methods

Delineation

Cross-sectional, observational study (registry) with longitudinal follow-up.

Hospital Selection

The public and private hospitals that participated in the Registry of Decompensated Heart Failure of the Department of Heart Failure of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology were chosen by the research committee. A fixed number of institutions was allocated for each one of the five regions of the country, and the number of patients per region was defined based on the absolute number of hospitalizations by region in the year 2004 according to the IBGE (Supplement II).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The methods of BREATHE, as well as its inclusion and exclusion criteria, have been previously described13.Patients older than 18 years, admitted to public or private hospitals with a definitive clinical profile of HF confirmed by the Boston criteria were considered eligible for the study14.Those patients undergoing myocardial revascularization procedures (coronary angioplasty or surgery) in the last month of the selection and who presented signs of HF secondary to sepsis were excluded from the study.

Definitions of the Study:

a) Clinical and Hemodynamic Profile:

The clinical and hemodynamic profile was defined according to the classification of Stevenson15, in four hemodynamic profiles according to the findings on physical examination of pulmonary congestion and peripheral perfusion. Patients with acute HF are generally in one of the following subgroups: 1) presence of pulmonary congestion without signs of hypoperfusion (wet and warm); 2) presence of pulmonary congestion associated with hypoperfusion (wet and cold); and 3) hypoperfusion without pulmonary congestion (dry and cold).

b) HF Treatment Targets Doses:

Target doses for the treatment of acute HF, for purposes of evaluation of the data from this study, were the same as those recommended by the II Guideline of Acute Heart Failure of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology16.

c) Causes of HF Decompensation:

The main causes of decompensation analyzed included infection, decompensation from acute valvular disease, poor adherence to drug therapy, excessive sodium intake in the last week, arrhythmias and pulmonary embolism. The classification was determined by the clinical judgment of the local investigator according to the patient’s report.

Follow-up

For the present analysis, in addition to hospital admission data, data were collected during hospitalization until the date of medical discharge or intrahospital death.

Outcomes of Interest

The primary outcome of this study was the all-cause intrahospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients who received interventions with proven benefit demonstrated by care quality indicators (use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEi] / angiotensin II receptor blockers [ARB] and use of beta-blockers), readmissions due to HF and cardiovascular mortality.

Ethical Aspects

The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa, CEP) of the Hospital do Coração de São Paulo, SP (HCor) on February 1st, 2011, under the registration number 144/2011, and following that, each participating center also had their protocols approved by their own CEPs. All patients signed a Free and Informed Consent Form and the clinical study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the current revision of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Management

The management of the data was performed using the EDC (Electronic Data Capture) system. Medical charts were transcribed by Web-charts, sent to the central coordinating center, and incorporated into a database for validation. Quality control of the data of the study occurred mainly by central checking in search of possible inconsistencies (data without biological plausibility) or incomplete data, and was reported to the participating centers for confirmation and/or correction. The Department of Heart Failure of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology was responsible for the management of the data of the study.

Sample Size

The first phase of the Brazilian Registry of Decompensated HF predicted the evaluation of 1,200 admissions to the public and private network in different regions of Brazil. This sample size was determined to represent the largest Brazilian prospective study of decompensated HF, involving all regions of the country, allowing identification of regional differences in intrahospital mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were described as medians (interquartile range) or means (standard deviation) according to the distribution of the variable, and the categorical variables as absolute and relative frequencies. Normality was evaluated with the visual inspection of histograms and application of the Shapiro-Wilks test of normality. Age distribution was compared among regions according to a model of analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the relationship between etiology and region was determined by the chi-square test. The software SAS 9.3 (Statistical Analysis System, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analysis of the data17.

Results

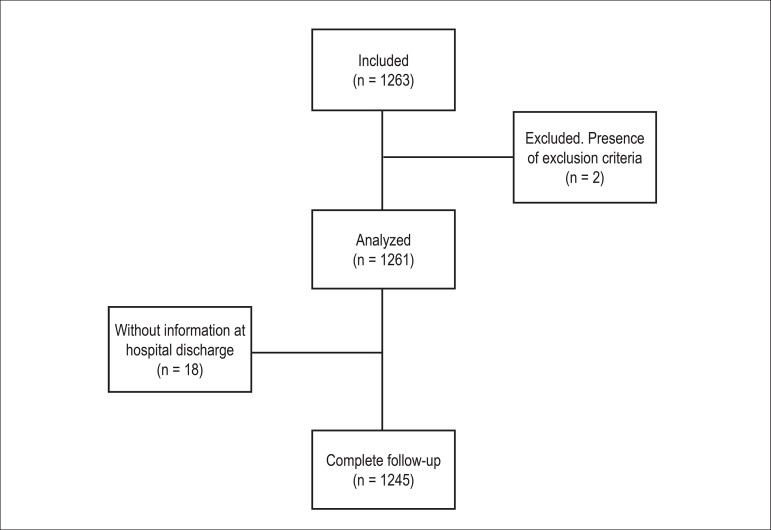

Between February 2011 and December 2012, 1,263 patients were included in 51 centers from different Brazilian regions (2 centers in the Northern region [164 patients], 13 centers in the Northeast [209 patients], 5 centers in the Midwest [66 patients], 33 centers in the Southeast [652 patients] and 5 centers in the South [172 patients]). Two patients were excluded from the analysis for meeting exclusion criteria. The flow diagram can be found in Supplement II.

The average age of the patients was 64±16 years, with 73.1% above the age of 75 years and 60% women. Most patients were self-reportedly white (59%), admitted to the public network/Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS; 64.8%) and from the South/Southeast regions (65.2%). Slightly over half of the patients included had left ventricular systolic dysfunction (58.7%), and the vast majority (70.8%) was hypertensive. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the studied sample, including demographics and prior medical history.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the cohort

| Variables | BREATHE (n = 1,261) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean+/-SD*) | 64.1 ± 15.9 |

| Male gender (%) | 40.0 |

| Prior acute myocardial infarction (%) | 26.6 |

| Hypertension (%) | 70.8 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 36.7 |

| Prior stroke /TIA§(%)† | 12.6 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 27.3 |

| Depression (%)† | 13.5 |

| Occlusive peripheral arterial disease (%)† | 10.8 |

| Chronic renal failure (%)† | 24.1 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%)† | 34.0 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (%) | 12.7 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (average/-+/-SD) | 38.8 ± 16.5 |

| Sodium (mean+/-SD) | 137±16 |

| Creatinine (mean+/-SD) | 1.7 ± 4.8 |

| BNP (median (IQR¶)) | 1,075 (518; 1,890) |

SD: standard deviation;

Values calculated on a total of 1,255 patients with complete information;

TIA: transient ischemic attack; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide;

IQR: interquartile range.

The average age distribution by region showed a statistically significant difference with the inclusion of patients of more advanced age in the Southeastern and Southern regions and younger patients in the Northern region (66±15 years versus 59±17 years, p = 0.019).

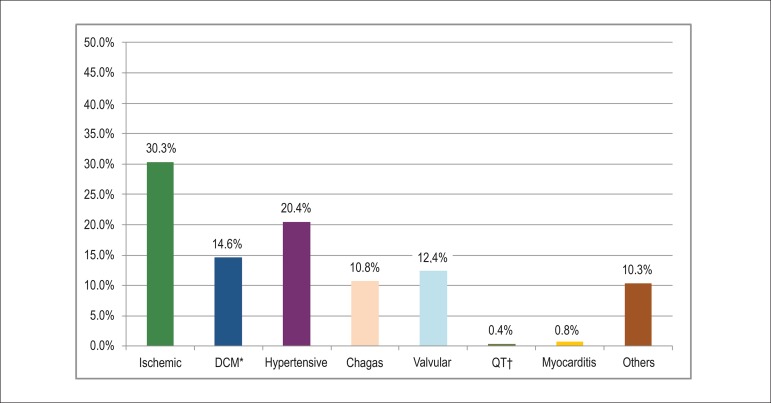

The hypertensive and ischemic etiologies prevailed in the studied population, affecting 30.1% and 20.3% of the patients, respectively. Around 11% of the patients had a diagnosis of Chagas disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of etiologies of heart failure in the BREATHE registry. * DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy; † QT: secondary to chemotherapy.

In the analysis of the etiologies by region, patients from the South, Southeast and Northeast showed a predominance of the ischemic etiology (33.6%, 32.6%, and 31.9%, respectively). In patients in the Northern region the hypertensive etiology (37.2%) predominated, while among patients in the Northern region the Chagasic etiology predominated (42.4%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of etiologies according to Brazilian regions

| Etiology | South | Southeast | Midwest | Northeast | North | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 172 | 100 | 652 | 100 | 66 | 100 | 209 | 100 | 164 | 100 | 1,263 | 100 |

| Ischemic | 58 | 33.6 | 213 | 32.6 | 15 | 22.8 | 67 | 31.9 | 27 | 16.5 | 380 | 30 |

| Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy | 12 | 7 | 93 | 14.3 | 4 | 6.1 | 41 | 19.6 | 33 | 20.1 | 183 | 14.5 |

| Hypertensive | 56 | 32.6 | 98 | 15 | 7 | 10.6 | 34 | 16.3 | 61 | 37.2 | 256 | 20.3 |

| Chagas disease | 4 | 2.3 | 80 | 12.3 | 28 | 42.4 | 13 | 6.2 | 11 | 6.7 | 136 | 10.8 |

| Valvular disease | 24 | 14 | 80 | 12.3 | 2 | 3 | 30 | 14.4 | 20 | 12.2 | 156 | 12.4 |

| Secondary to chemotherapeutic agents | 1 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.4 |

| Myocarditis | 2 | 1.2 | 5 | 0.8 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0.8 |

| Others | 15 | 8.7 | 74 | 11.3 | 8 | 12.1 | 20 | 9.6 | 12 | 7.3 | 129 | 10.2 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0.6 |

The main causes of HF decompensation were poor adherence to medication (30%), followed by infections (23%) and inadequate control of water and sodium intake (9%), as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Distribution of causes of heart failure decompensation

| Decompensation cause | % (n=1,250) |

|---|---|

| Infection | 22.7 |

| Poor medication adherence | 29.9 |

| Increased ingestion of sodium and water* | 8.9 |

| Acute valvular disease | 6.6 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 12.5 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.4 |

| Others | 32.4 |

Total with complete information 1,242 patients.

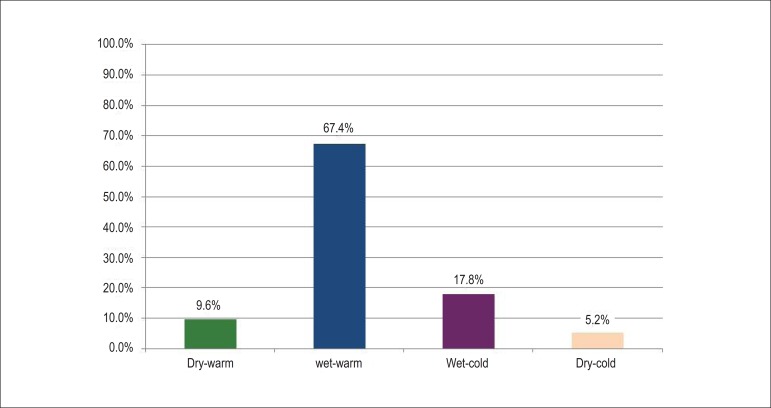

As for the clinical and hemodynamic profile on hospital admission, the prevalence was for the wet-warm profile, totaling 67.4% of the cases, whereas the wet-cold and dry-cold profiles accounted for 17.8% and 5.2%, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hemodynamic profile on hospital admission.

Table 4 lists the main procedures performed during hospitalization, as well as the mortality rate during hospitalization. The sum of the deaths in the first 24 hours (17 patients) and after this period (140 patients) totaled 12.6% of the studied cohort. Valve replacement prevailed among the procedures during hospitalization, occurring in 156 patients.

Table 4.

Events and procedures during hospitalization

| Events/procedures | % | (n/total) |

|---|---|---|

| Intrahospital mortality | 12.6 | (1,57/1,245) |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 0.7 | (9/197) |

| Valve replacement | 12.4 | (156/197) |

| Heart transplantation | 1.2 | (15/197) |

| Coronary angioplasty | 1.5 | (19/197) |

| Implantable defibrillator/Resynchronizer | 1.2 | (15/197) |

| Cardiac pacemaker | 1.7 | (22/197) |

* Of the total, only 197 patients had procedures performed during hospitalization.

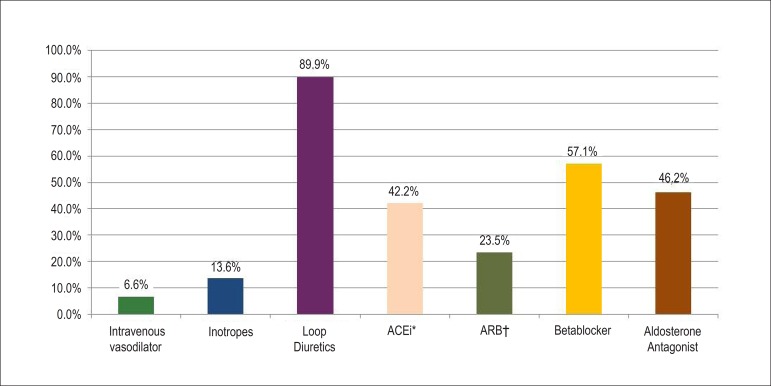

For the treatment of acute HF during hospitalization the use of loop diuretics prevailed (89.8%), followed by beta-blockers (57.1%). The use of intravenous vasodilators (6.6%) and inotropic agents (13.6%) represented a small portion of the therapy in this population (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Medications administered during the hospital stay. * ACEi: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; †ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker.

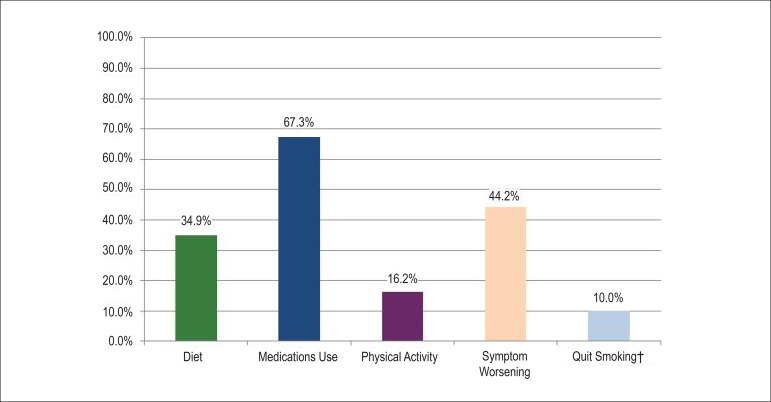

According to the indicators of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), 63.7% of the patients received guidelines on hospital discharge about the correct use of medications, whereas only 34.9% and 16.2% were advised about the diet to be followed at home and prescription of physical activity, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Guidelines on hospital discharge according to the indicators of care quality during hospitalization for heart failure (according to the JCAHO*). * Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization. † Applicable to smokers

Discussion

The main findings of this analysis of the study BREATHE are: 1) baseline characteristics show a populational profile of predominantly elderly patients, mainly in the Southern and Southeastern regions of Brazil; 2) poor drug adherence was the factor most frequently associated with decompensation; 3) the prescription of drugs, mainly vasodilators, according to current evidence was below the expected rate for this population; and 4) high intrahospital mortality rate.

Patients with advanced age accounted for an important segment of the sample studied in BREATHE and predominated in the South and Southeast regions, where the ischemic etiology was also more prevalent.

Among patients with chronic diseases, approximately 50% do not take medications as prescribed. This poor drug adherence leads to increased morbidity, mortality and costs18.In addition to that, advanced age is a risk factor for poor adherence which increases even more with polypharmacy, increasing the likelihood of adverse events.

Studies about drug adherence demonstrate highly variable rates of adherence among patients with HF. A study reported adherence rates of 79% for ACEi/ARB, 65% for beta-blockers and 56% for spironolactone after five years from the first hospitalization for HF19. In contrast, the noncompliance rate based on pill count was much lower in the CHARM study, in which 11% of the patients took less than 80% of the prescribed pills20.

Adherence is associated with several factors and should not be regarded as the sole responsibility of the patient. The BREATHE study pointed out that only slightly more than 50% of the patients received guidelines for correctly taking the medications, and only 43.5% were advised about the recognition of worsening of symptoms and future appointments. Preliminary evidence shows that around 35% of the inpatients with acute HF receive appropriate instructions on hospital discharge, with academic centers showing worse performance in this indicator of the JCAHO21.

Of still greater relevance and impact on the prescription of medication on discharge is the medication introduced during the hospital phase. This analysis demonstrates that there are still considerable gaps in the treatment of acute HF in Brazil. The treatment frequently does not follow current published guidelines, which may contribute to the high morbidity, mortality and economic cost of this syndrome16.

The IMPROVE-HF study showed that the addition of each evidence-based therapy was associated with a decreased risk of mortality in 24 months, with incremental benefit. This strong positive association between the use of evidence-based therapies and improved risk-adjusted survival reached a plateau after 4-5 therapies included in the therapeutic armamentarium of the patient with HF22.

Despite the fact that the clinical hemodynamic profile wet-warm was the most common in the present study, only 6.6% of the population received intravenous vasodilators, whereas 42.2% of the patients received ACEi during the hospital phase. Around 18% of the patients showed a wet-cold profile on hospital admission, but only 13.6% received inotropes. Beta-blockers were prescribed to only 57.1% of the studied sample. In contrast, loop diuretics were prescribed to approximately 90% of the patients.

Results from the analysis of the ADHERE registry suggest that starting vasodilator therapy in the emergency department correlates with shorter hospital stays and fewer transfers to the intensive care unit, as well as higher percentages of asymptomatic patients at hospital discharge23. Additionally, there was a substantial improvement in the survival rate of patients receiving intravenous vasodilators (nitroglycerin or nesiritide), compared with those who received intravenous inotropes (dobutamine or milrinone)24. However, it is possible that patients requiring inotropic therapy have a more advanced form of HF than patients who receive vasodilators.

Analysis of the Euro Heart Survey clearly showed that patients included in randomized clinical trials are a highly selected group and that only a small proportion of the patients in this registry would be eligible. However, beta-blockers and ACEi were prescribed for less than half of the eligible patients and the doses used were below those which have proven to be effective. Therefore, the lack of similarity between patients with HF in clinical practice and those in clinical trials does not adequately explain the underutilization of the therapy25.

Intrahospital treatment invariably has a direct impact on clinical events during hospitalization. The prognosis of HF is reserved and directly related to the loss of functional capacity. Data from the Framingham study showed a median survival rate after diagnosis of 1.7 years for men and 3.2 years for women. The high mortality, morbidity and impairment of quality of life related to HF affects primarily the elderly. Although we may observe a consistent and significant survival benefit in patients with HF with use of aggressive pharmacological strategies, the annual mortality of this disease remains high26-31. The CONSENSUS (Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study)32 and PROMISE (Prospective Randomized Milrinone Survival Evaluation)33 studies, for example, identified a high proportion of patients with annual mortality exceeding 30%. In more recent studies, the mortality of patients with functional class III-IV after 1 year of optimized treatment, including the routine use of ACEi and beta-blockers, was approximately 10-15%34. Although these values are encouraging, such mortality rates are also similar to those observed in many neoplastic diseases.

As for intrahospital mortality, it affects between 3% to 4% of the patients admitted for acute HF in prior studies35, whereas the mortality rate in the BREATHE registry exceeds in two times the rates from American and European registries. In the ADHERE study, intrahospital mortality was 4.0%, and the average hospital stay was 4.3 days36.Similar to the American registry, the Euro Heart Survey presented an overall intrahospital mortality rate of 3.8%, with 90.1% due to a cardiovascular cause. Higher mortality rates were observed in the presence of cardiogenic shock37.

Some limitations inherent to the design of BREATHE should be considered in the interpretation of its results. The diagnosis of acute HF was based only on the Boston criteria and the date of onset of symptoms was not defined, therefore it was not possible to differentiate new acute HF from exacerbation of chronic HF. Consequently, since the population is heterogeneous, the analysis of treatment and prognosis will require appropriate adjustment. In addition, the number of missing data was elevated due to some variables whose completion was not mandatory, interfering with the results found.

Conclusion

BREATHE is the first Brazilian registry of acute HF and its results point to the high rate of intrahospital mortality related to low rates of evidence-based therapy prescribed during hospitalization, as well as low percentage of medical guidelines on hospital discharge of patients hospitalized for acute HF in different regions of Brazil. New strategies must be adopted to ensure improvement in the quality of hospital care of this disease.

Supplement I

Supplement I.

Distribution of the BREATHE patients by region (planned versus included)

| Major Regions | Hospitalization in health establishments in the year of 2004 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total IBGE | Total BREATHE referred | Total BREATHE Included | |

| Brazil | 23,252,613 (100%) | 1,200 | 1,263 |

| North | 1,746,554 (8%) | 96 | 164 |

| Northeast | 5,254,978 (23%) | 276 | 209 |

| Southeast | 10,794,799 (46%) | 552 | 652 |

| South | 3,671,762 (16%) | 192 | 172 |

| Midwest | 1,784,520 (8%) | 96 | 66 |

Supplement II

Supplement II.

Flow diagram of the BREATHE study.

List of participants BREATHE

Hospital de Clínicas Gaspar Viana: Helder José Lima Reis; Hospital de Base FAMERP: Paulo Roberto Nogueira; Hospital do Coração: Ricardo Pavanello; Hospital São Lucas – PUCRS: Luiz Claudio Danzmann; Hospital de Messejana: João David de Souza Neto; Instituto Dante Pazzanese: Elizabete Silva dos Santos; Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre: Luis Eduardo Paim Rohde; InCor SP: Mucio Tavares de Oliveira Filho; Real Hospital Português: Silvia Marinho Martins; Hospital Universitário Clementino Fraga Filho: Marcelo Iorio Garcia; Hospital Total Cor: Antonio Baruzzi; Hospital Universitário Prof. Alberto Antunes: Maria Alayde Mendonça da Silva; Hospital Barra D’Or: Ricardo Gusmão; Hospital do Coração de Goiás: Aguinaldo Figueiredo de Freitas Júnior; Hospital Vera Cruz: Fernando Carvalho Neuenschwander; Hospital Universitário de Londrina: Manoel Fernandes Canesin; Hospital Copa D’or: Denilson Campos de Albuquerque; Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Goiás: Salvador Rassi; Instituto Cardiopulmonar: Eduardo Darzé; Santa Casa de Votuporanga: Mauro Esteves Hernandes; Hospital Universitário Pedro Ernesto: Ricardo Mourilhe Rocha; São Lucas Médico Hospitalar: Antonio Carlos Sobral Sousa; Hospital Universitário Presidente Dutra-HUUFMA: Jose Albuquerque de Figueiredo Neto; Centro de Pesquisa da Clínica Médica e Cardiologia da UNIFESP: Renato D. Lopes; Unidade de Insuficiência Cardíaca – InCor: Edimar Alcides Bocchi; Hospital Quinta Dor: Jacqueline Sampaio; Hospital Lifecenter: Estêvão Lanna Figueiredo; Xeno Diagnósticos Dante Pazzanese: Abilio Augusto Fragata Filho; Fundação Bahiana de Cardiologia: Alvaro Rabelo Alves Júnior; Instituto de Cardiologia do Distrito Federal: Carlos V. Nascimento; Hospital Auxiliar do Cotoxó: Antonio Carlos Pereira-Barretto; Fundação Beneficência Hospital de Cirurgia/ Hospital do Coração: Fabio Serra Silveira; Hospital Santa Izabel: Gilson Soares Feitosa; Hospital Regional Hans Dieter Schmidt: Conrado Roberto Hoffmann Filho; Hospital Univ. Antonio Pedro – UFF: Humberto Villacorta Júnior; Hospital Universitário São Jose: Sidney Araújo; Hospital das Clínicas de Botucatu UNESP Botucatu: Beatriz Bojikian Matsubara; Hospital Santa Paula: Otávio Gebara; Casa de Saúde São José: Gustavo Luiz Gouvea de Almeida; Hospital das Clínicas da UFMG: Maria da Consolação Vieira Moreira; Hospital Madre Tereza: Roberto Luiz Marino; São Bernardo Apart Hospital: João Miguel de Malta Dantas; Instituto Nacional de Cardiologia: Marcelo Imbroinise Bittencourt; Hospital da Cidade: Marcelo Silveira Teixeira; Hospital Rios Dor: Elias Pimentel Gouvea; Hospital das Clínicas de Ribeirão Preto/ USP-FMRP: Marcus Vinícius Simões; Santa Casa de São Paulo: Renato Jorge Alves; Hospital Espanhol: Fabio Villas-Boas; Unidade de Miocardiopatia InCor: Charles Mady; Hospital Escola Alvaro Alvim: Felipe Montes Pena; Hospital Univ. João de Barros Barreto – UFPA: Eduardo Costa.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research: Albuquerque DC, Souza-Neto JD, Bacal F, Rohde LEP. Acquisition of data: researchers BREATHE, Albuquerque DC, Souza-Neto JD, Rohde LEP, Bernardez- Pereira S, Almeida DR. Analysis and interpretation of the data: Albuquerque DC, Rohde LEP, Bernardez-Pereira S, Berwanger O. Statistical analysis: Bernardez-Pereira S. Obtaining financing: Albuquerque DC. Writing of the manuscript: Albuquerque DC, Souza-Neto JD, Bacal F, Rohde LEP, Bernardez- Pereira S, Almeida DR. Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Albuquerque DC, Souza- Neto JD, Bacal F, Rohde LEP, Bernardez-Pereira S, Berwanger O, Almeida DR.

Potential Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by Departamento de Insuficiência Cardíaca da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia.

Study Association

This study is not associated with any thesis or dissertation work.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, et al. American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee. Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention. Council on Clinical Cardiology. Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Stroke Council Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–619. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bocchi EA. Heart failure in South America. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2013;9(2):147–156. doi: 10.2174/1573403X11309020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministério da Saúde . Datasus: mortalidade - 1996 a 2012, pela CID-10 - Brasil. Brasília, DF: 2008. [citado em 2014 dez 03]. [Internet] Disponível em: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm.exe?sim/cnv/obt10uf.def. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roger VL. Epidemiology of heart failure. Circ Res. 2013;113(6):646–659. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon SD, Dobson J, Pocock S, Skali H, McMurray JJ, Granger CB, et al. Candesartan in heart failure: assessment of reduction in mortality and morbidity (CHARM) investigators. Influence of nonfatal hospitalization for heart failure on subsequent mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116(113):182–187. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.696906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin MH, Goldman L. Correlates of early hospital readmission or death in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79(12):1640–1644. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin MH, Goldman L. Correlates of major complication or death in patients admitted to the hospital with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(16):1814–1820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin MH, Goldman L. Factors contributing to the hospitalization of patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Public Heath. 1997;87(4):643–648. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart S, Blue L, Capewell S, Horowitz JD, McMurray JJ. Poles apart, but are they the same? A comparative study of Australia and Scottish patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3(2):249–255. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(00)00144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tavares L, Silva GP, Pereira SB, Souza G, Pozam R, Coutinho S, et al. Análise ecocardiográfica e etiológica dos pacientes internados por insuficiência cardíaca na cidade de Niterói. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2002;79(supl.4):35–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavares L, Silva GP, Pereira SB, Souza G, Pozam R, Victer H, et al. Co-morbidades e fatores de descompensação dos pacientes internados por insuficiência cardíaca descompesada na cidade de Niterói. Arq Brás Cardiol. 2002;79(supl.4):35–35. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Investigadores do BREATHE Racionalidade e métodos - estudo BREATHE - I Registro brasileiro de insuficiência cardíaca. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2013;100(5):390–394. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson KJ, Lee DC, Goroll AH, Leahy M, Johnson RA. An analysis of physicians' reasons for prescribing long-term digitalistherapy in outpatients. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38(9):733–739. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevenson LW, Perloff JK. The limited reliability of physical signs for estimating hemodynamics in chronic heart failure. JAMA. 1989;261(6):884–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montera MW, Almeida RA, Tinoco EM, Rocha RM, Moura LZ, Réa-Neto A, et al. Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia II Diretriz brasileira de insuficiência cardíaca aguda. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009;93(3) supl.3:1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker Glenn A., Shostak Jack. Common Statistical Methods for Clinical Research with SAS Examples. 3rd ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(4):304–314. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, Schramm TK, Hansen ML, Buch P, et al. Persistent use of evidence-based pharmacotherapy in heart failure is associated with improved outcomes. Circulation. 2007;116(7):737–744. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.669101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granger BB, Swedberg K, Ekman I, Granger CB, Olofsson B, McMurray JJ, et al. CHARM Investigators Adherence to candesartan and placebo and outcomes in chronic heart failure in the CHARM programme: double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9502):2005–2011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67760-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fonarow GC, Yancy CW, Heywood JT, ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee.Study Group, and Investigators Adherence to heart failure quality-of-care indicators in US hospitals: analysis of the ADHERE Registry. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(13):1469–1477. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Curtis AB, Gheorghiade M, Liu Y, Mehra MR, et al. Incremental reduction in risk of death associated with use of guideline-recommended therapies in patients with heart failure: a nested case-control analysis of IMPROVE HF. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1(1):16–26. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peacock WF, Fonarow GC, Emerman CL, Mills RM, Wynne J, ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators. Adhere Study Group Impact of early initiation of intravenous therapy for acute decompensated heart failure on outcomes in ADHERE. Cardiology. 2007;107(1):44–51. doi: 10.1159/000093612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abraham WT, Adams KF, Fonarow GC, Costanzo MR, Berkowitz RL, LeJemtel TH, et al. ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators. ADHERE Study Group In-hospital mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure requiring intravenous vasoactive medications: an analysis from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenzen MJ, Boersma E, Reimer WJ, Balk AH, Komajda M, Swedberg K, et al. Under-utilization of evidence-based drug treatment in patients with heart failure is only partially explained by dissimilarity to patients enrolled in landmark trials: a report from the Euro Heart Survey on Heart Failure. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(24):2706–2713. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richembacher PR, Trindade PT, Haywood GA, Vagelos RH, Schroeder JS, Willson K, et al. Transplant candidates with severe left ventricular dysfunction managed with medical treatment: characteristics and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27(5):1192–1197. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. The natural history of congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1971;285(26):1441–1446. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franciosa JA, Willen M, Ziesche S, Cohn JN. Survival in men with severe chronic left ventricular failure to either coronary heart disease or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51(5):831–836. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohn JN, Archibald DG, Ziesche S, Franciosa JA, Harston WE, Tristani FE, et al. Effect of vasodilatador therapy on mortality in chronic congestive heart failure: results of a Veterans Administration Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(24):1547–1552. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198606123142404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The SOLVD Investigators Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(5):293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moyé LA, Basta L, Brown EJ, Jr, Cuddy TE, et al. Effect of captopril on mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarctionresults of the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Trial. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(10):669–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The CONSENSUS Trial Study Group Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure (CONSENSUS) N Engl J Med. 1987;316(23):1429–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706043162301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massie B, Bourassa M, DiBianco R, Hess M, Konstam M, Likoff M, et al. for The Amrinone Multicenter Study Group: long term oral administration of amrinone for congestive heart failure: lack of efficacy in a multicenter controlled trial. Circulation. 1985;71(5):963–971. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.5.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Packer M1, Fowler MB, Roecker EB, Coats AJ, Katus HA, Krum H, et al. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure: results of the carvedilol prospective randomized cumulative survival (COPERNICUS) study. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(22):1651–1658. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Francis GS. Acute heart failure: patient management of a growing epidemic. Am Heart Hosp J. 2004;2(4 ) Suppl 1:10–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adams KF, Jr, Fonarow GC, Emerman CL, LeJemtel TH, Costanzo MR, Abraham WT, et al. ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for heart failure in the United States: rationale, design, and preliminary observations from the first 100,000 cases in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Am Heart J. 2005;149(2):209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maggioni AP, Dahlström U, Filippatos G, Chioncel O, Crespo Leiro M, Drozdz J, et al. Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (HFA) EURObservational Research Programmeregional differences and 1-year follow-up results of the Heart Failure Pilot Survey (ESC-HF Pilot) Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(7):808–817. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]