Abstract

Objective: Positive deviance methodology has been applied in the developing world to address childhood malnutrition and has potential for application to childhood obesity in the United States. We hypothesized that among children at high-risk for obesity, evaluating normal weight children will enable identification of positive outlier behaviors and practices.

Methods: In a community at high-risk for obesity, a cross-sectional mixed-methods analysis was done of normal weight, overweight, and obese children, classified by BMI percentile. Parents were interviewed using a semistructured format in regard to their children's general health, feeding and activity practices, and perceptions of weight.

Results: Interviews were conducted in 40 homes in the lower Rio Grande Valley in Texas with a largely Hispanic (87.5%) population. Demographics, including income, education, and food assistance use, did not vary between groups. Nearly all (93.8%) parents of normal weight children perceived their child to be lower than the median weight. Group differences were observed for reported juice and yogurt consumption. Differences in both emotional feeding behaviors and parents' internalization of reasons for healthy habits were identified as different between groups.

Conclusions: We found subtle variations in reported feeding and activity practices by weight status among healthy children in a population at high risk for obesity. The behaviors and attitudes described were consistent with previous literature; however, the local strategies associated with a healthy weight are novel, potentially providing a basis for a specific intervention in this population.

Introduction

Overweight and obesity affect 25% of the US population of children ages 2–6 years. In Cameron County of south Texas, which has an 80% Hispanic population and 32% poverty, the prevalence is even higher with 40% of children in the same age range being overweight or obese.1 Early childhood weight status tracks through adolescence and adulthood2,3; therefore, early intervention is both needed and has great public health significance.

A primary challenge of overweight and obesity prevention and treatment in children is how to maintain success once achieved. In school-aged children, evidence exists that comprehensive, intensive behavioral interventions and school-based programs work in targeting overweight and obesity.4 In contrast, few interventions have been attempted in preschool children, and there is minimal information specific to Hispanic children.5–7 Programs that have shown promising results in younger children have used family-centered, behavioral approaches using trained facilitators or instructors.7 A major challenge of all obesity prevention and treatment programs in children is sustainability after research teams leave given that the facilitators are not a natural component of the community.8

Positive deviance is an approach to problem solving that recognizes that not all individuals with risk factors for a given outcome experience that outcome—some deviate from the norm in a positive way. This theory posits that there are some individuals who may thrive despite an adverse environment and without extra resources. This approach has been tested and has proven successful in addressing malnutrition,9 iron deficiency anemia,10 and recently adult obesity.11 The benefit of a positive deviance strategy is that it utilizes local resources and people, deriving solutions from the community, thus enhancing both acceptability and sustainability in the community.

The steps in a positive deviance approach are traditionally (1) defining and identifying the positive deviants, (2) using open-ended methods to draw out and identify the skills and behaviors that enable their success, (3) testing whether these positive deviant behaviors work outside of their identified context, and (4) dissemination of the behaviors shown to be effective.12 Our aim was to use a positive deviance approach to examine factors for maintaining a healthy weight among a high-risk population in south Texas, the first two steps outlined above. We used quantitative methods to characterize known risk factors for early childhood obesity in a high-risk population, and we used qualitative methods to search for more nuanced differences between the groups.

Methods

Design and Sample Population

Subjects were recruited from two pediatric clinics in Harlingen, Texas. Parent-child dyads were recruited if their child was between 24 and 72 months of age and whose parents could speak English. Exclusion criteria were a diagnosis of moderate-to-severe developmental delay, seizure disorder, diabetes, or any genetic diagnosis or cerebral palsy.

We defined positive deviants for this study as parent-child dyads with a normal weight child despite an adverse environment (high local prevalence of overweight and obesity1) and circumstances (from a low-socioeconomic background). The parent's weight was not considered in the definition; they could be of any weight. The goal recruitment was at least 10 parent-child dyads or until data saturation in each of the following groups of children: normal weight defined as >5th–85th BMI percentile for age; overweight defined as >85th–95th BMI percentile; and obese defined as >95th BMI percentile.

The children were weighed using a standardized portable scale and measured using a stadiometer. Parent-child dyads were interviewed using a semistructured questionnaire in their homes by two members of the research team. Interviews were conducted between March and October 2013. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (San Antonio, TX); all parents provided written consent.

Measures

The questionnaire was developed to examine both the known influences on early childhood weight and had separate sections for more open-ended questions to elicit themes or patterns not prespecified by the research team. The prespecified questions examined general demographic information, including income, education, and family size, using questions from the National Survey of Children's Health,13 food insecurity and nutrition assistance.14 We conducted a structured, multiple-pass dietary recall covering 24 hours after the traditional method of a list of all foods consumed, then a follow-up pass with time and setting with further probing and collection of details on the items consumed, modeled after the methods used by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys15 with differences of a single day administration, which has been used to document food patterns,16 and that they were conducted in participants' homes.

Open-ended, nonstandardized questions included general perceptions of health, feeding practices, and environment for the child; food purchasing and preparation habits; roles of caregivers and family interactions; general health knowledge; questions related to screen time and activity; breastfeeding history; and self-reported parental height and weight (questionnaire available as an online supplement). Perception of weight was assessed using a validated visual scale of body image sizes,17 with the same images depicted for two questions: what the child appears to be and the parent's ideal appearance for their child.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data, including demographic variables and reported food frequency using a 24-hour dietary recall format, were extracted from the interviews. Descriptive analyses using one-way analysis of variance comparing means across the three weight-based groups (normal weight, overweight, and obese) or using Fisher's exact test were completed. Shapiro-Wilk's tests for normality were run on continuous variables and Kruskal-Wallis' tests used for non-normal variables. All statistics were conducted using SPSS software (19.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Qualitative Analysis

The transcripts were read first by the primary interview team to assess for quality. The research team then read each interview line by line, not blinded to participant category.18 The approach to theme development used grounded theory starting with codes around individual terms or phrases, building concepts and themes from those codes.19 After discussion and reanalysis both within (normal, overweight, and obese groups) and across groups, the themes and subthemes were resorted and recoded; word frequency analysis was applied to the dietary reports using TAPoR (Ontario, Canada). Emerging themes were rechecked using the original transcripts for potential disconfirming evidence. Positive deviance behaviors were defined when they occurred in a majority of the dyads in the normal weight group and did not occur in the majority of the obese group.

Results

The three groups of children (normal weight, overweight, and obese) were similar in regard to their demographics with significant epidemiological risks for obesity: primarily Hispanic, 87.5%; poor with 59.0% below the 2013 federal poverty line; 66.7% of families reported food assistance program use (Table 1). The parents of obese children had a substantially higher mean BMI, compared to the parents of the overweight or normal weight children (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Subjects and Their Parents Grouped by Weight Status

| Normal (5th–85th) | Overweight (85th–95th) | Obese (>95th) | All | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child's age in months, mean (SD) | 45.6 (12.5) | 46 (11.7) | 46.9 (11.8) | 46.2 (11.8) | 0.95 |

| Sex, % male (n) | 62.5 (10) | 55.6 (5) | 40.0 (6) | 52.5 (21) | 0.51 |

| Ethnicity, % Hispanic (n) | 93.8 (15) | 77.8 (7) | 86.7 (13) | 87.5 (35) | 0.59 |

| Language at home, % English (n) | 75 (12) | 88.9 (8) | 80 (12) | 32 (80) | 0.48 |

| Education | 0.46 | ||||

| % high school or less (n) | 31.3 (5) | 33.3 (3) | 53.3 (8) | 40.0 (16) | |

| % any college or higher (n) | 68.8 (11) | 66.7 (6) | 46.7 (7) | 60.0 (24) | |

| Income, % in group (n) | 0.36 | ||||

| <100 FPL | 43.8 (7) | 62.5 (5) | 73.3 (11) | 59.0 (23) | |

| 100–200 FPL | 31.3 (5) | 37.5 (3) | 20.0 (3) | 28.2 (11) | |

| >200 FPL | 25.0 (4) | 0 | 6.7 (1) | 12.8 (5) | |

| BMI of parent, mean (SD) | 30.1 (5.2) | 28.5 (7.3) | 35.3 (7.2) | 31.7 (7.3) | 0.04 |

| Child's BMI percentile, mean (SD) | 56 (19.5) | 90.8 (2.9) | 98.7 (1.4) | 79.9 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| Food insecurity, % yes (n) | 6.3 (1) | 12.5 (1) | 26.7 (4) | 15.4 (6) | 0.28 |

| Home status, % own (n) | 46.7 (7) | 44.4 (4) | 66.7 (10) | 53.8 (21) | 0.54 |

| Food stamps, % yes (n) | 62.5 (10) | 77.8 (7) | 64.3 (9) | 66.7 (26) | 0.83 |

| Family size, median (IQR) | 5 (4–6) | 4 (4–5) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.25 |

Analysis of variance used to compare groups with normal distributions; for non-normal distributions, Kruskal-Wallis' test used with median (25th–75th IQR) reported.

SD, standard deviation; FPL, federal poverty level; IQR, interquartile range.

When caregivers were asked whether they thought their child was at a healthy weight, 93.3% of the parents of normal weight children responded “yes,” in comparison to 88.9% and 57.1% of caregivers of overweight and obese children, respectively (p=0.05; Table 2). Using the pictures representing different weight children, the larger child was identified as the “child most like” in 22.2% of the overweight group and in 53.3% of the obese group versus 0% of caregivers of normal weight children (p=0.001). There was no difference in perceived ideal weight (smaller, median, or larger) between the caregivers of the three groups.

Table 2.

Participant Data From Responses to Health Perceptions Questions, Food and Beverage Intake Estimates, and Activity and Screen Time Estimates

| Normal (5th–85th) | Overweight (85th–95th) | Obese (>95th) | All | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Think healthy weight, % yes (n) | 93.3 (14) | 88.9 (8) | 57.1 (8) | 78.9 (30) | 0.02 |

| Picture most like % (n) | <0.01 | ||||

| Smaller | 93.8 (15) | 55.6 (5) | 26.7 (4) | 60.0 (24) | |

| Median | 6.3 (1) | 22.2 (2) | 20.0 (3) | 15.0 (6) | |

| Larger | 0 (0) | 22.2 (2) | 53.3 (8) | 25.0 (10) | |

| Picture of ideal weight % (n) | 0.21 | ||||

| Smaller | 68.8 (11) | 33.3 (3) | 53.3 (8) | 55 (22) | |

| Median | 31.3 (5) | 55.6 (5) | 26.7 (4) | 35 (14) | |

| Larger | 0 | 11.1 (1) | 20 (3) | 10 (4) | |

| Difference in most like versus ideal % (n) | 0.01 | ||||

| Want smaller | 6.3 (1) | 22.2 (2) | 60.0 (9) | 30.0 (12) | |

| No change | 56.3 (9) | 33.3 (3) | 33.3 (5) | 42.5 (17) | |

| Want bigger | 37.5 (6) | 44.4 (4) | 6.7 (1) | 27.5 (11) | |

| Breast fed, % yes (n) | 50 (8) | 66.7 (6) | 40 (6) | 50 (20) | 0.52 |

| Milk consumed per day (oz), median (IQR) | 15 (12–18) | 12 (8–26) | 12 (7–28) | 12 (8–20) | 0.82 |

| Water consumed per day (oz), median (IQR) | 16 (12–28) | 24 (5–36) | 18 (10–38) | 16 (12–32) | 0.90 |

| Juice consumed per day (oz), median (IQR) | 8 (6–16) | 16 (13–20) | 11 (8–20) | 12 (8–16) | 0.05 |

| Soda consumed per day (oz), median (IQR) | 0 (0–4) | 4 (0–7) | 12 (0–16) | 0 (0–8) | 0.07 |

| Yogurt consumed as snack, % yes (n) | 56.3 (9) | 62.5 (5) | 20.0 (3) | 43.6 (17) | 0.05 |

| Fruit and vegetable intake, mean (SD) | 2.7 (1.6) | 3.5 (1.6) | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.8 (1.5) | 0.34 |

Analysis of variance used to compare groups with normal distributions; for non-normal distributions, Kruskal-Wallis' test used with median (25th–75th IQR) reported.

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

There was a trend toward less soda intake in the normal weight group (p=0.07) and less reported juice intake (p=0.05). There was no difference between the three groups in regard to reported vegetable and fruit consumption. Word frequency analysis identified yogurt in the normal weight group; post-hoc analysis showed less use of yogurt as a snack in obese children (p=0.05). The data on screen time and activity were not collected in a validated manner, but were rather extracted from the interviews; there were no major differences noted between the groups in either category, with parents reporting a median of 2.5 hours of screen time and a mean of 1.9 hours of physical activity (PA). We conducted a sensitivity analysis of the data looking only at the poorest subgroup, <100% of the federal poverty level (FPL). We found no difference in the patterns of food intake, activity, screen time, or any of the other independent variables between the poorest subset and the overall sample (data not shown).

Qualitative Results

Four overall themes emerged from the data: perceptions of what healthy is; health knowledge; health behaviors; and degree of control.

Perceptions of What Healthy Is

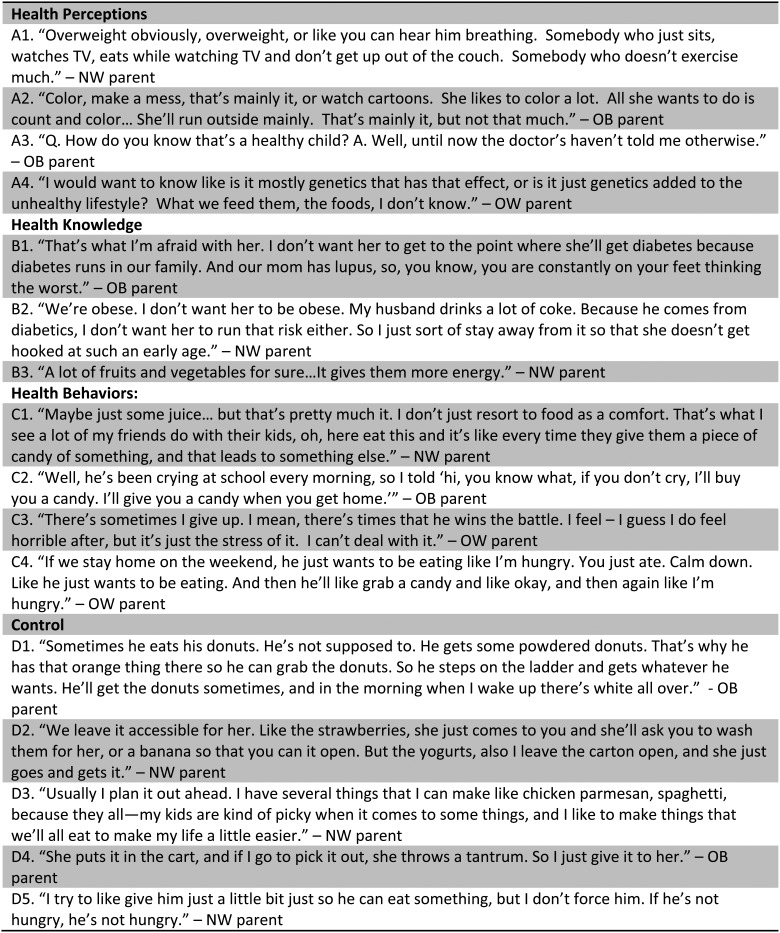

Whereas participants across all groups defined a healthy child as an “active” child, only parents of normal weight children described the converse, that an “inactive” child is an unhealthy child (Fig. 1, quotation A1). Similarly, descriptions of overweight as being part of “unhealthy” were mainly found in the normal weight group. “Play time” or “playing” without reference to PA were stronger foci in the obese group narrative versus a focus on “running around” and “moving” in the normal weight group (quotation A2).

Figure 1.

Overall themes with illustrative quotes of subthemes. NW, normal weight group; OW, overweight; OB, obese.

When describing why their own child was healthy, the overwhelming sentiment was that because no one had said anything, the child was healthy by default, in particular, the doctor's lack of input (quotation A3). In the overweight and obese groups, when queried on the cause of obesity, genetics was often postulated to play a role, whereas this was hardly mentioned in the normal weight group (quotation A4). Finally, in regard to health perceptions, sugar was widely viewed as a culprit in discussing “bad” foods, whereas calories were hardly mentioned at all; no differences emerged between groups.

Health Knowledge

Most parents used either the experience of a close family member or a past personal experience as the basis for why they were concerned about their child's health or why they did a particular health practice. However, only parents of the normal weight children described a link between that experience and the particular health practice. Good or bad foods, diabetes, and avoidance behaviors were three subthemes that emerged around this central theme. For example, whereas all groups described fruits and vegetables as healthy or soda as bad, parents of the normal weight group often described some specific reason for this belief “because they are high in fat” or “because it leads to diabetes” versus a more general “that's what I hear” or “that's what the doctor says” reference. Among both obese and normal weight children, one third of parents mentioned a member in their close family who had been diagnosed with diabetes. Parents of obese children expressed greater fear and concern when discussing diabetes, as compared to the other groups (Fig. 1, quotation B1). Parents of normal weight children reported a more concrete understanding of characteristics and behaviors that correlate with diabetes and appeared motivated by this knowledge to modify habits with their children (quotation B2). Avoidance of buying certain foods at the store to avoid consuming them at home was common across groups. However, parents of normal weight children described a specific health fact in describing why they avoided those foods versus a description of avoiding some bad behavior—“eating it all” or “having a tantrum about it” in the overweight and obese groups. The parents of normal weight children did not describe a different set of experiences, but rather a difference in their internal reactions to those experiences.

There was not a difference between the groups regarding knowledge of the suggested amount of fruits and vegetable servings for their child. One notable positive outlier behavior was leaving healthy foods available for snacks. Most parents reported independent snacking behaviors, but only normal weight dyads reported leaving out fruits or vegetables, compared with chips or “whatever they can find” in the overweight and obese groups. Regarding portion sizes, most parents referenced previous portion sizes consumed by their child, or used the child's plate size or a serving spoon as their measurement, without an objective reference. In the obese group of children, what parents described as a “snack” actually constituted a full meal.

Health Behavior

Emotional eating, or feeding the child when upset, was common in all groups. The major difference was parental reasoning for the food as a reward or bribe. Parents of normal weight children more often described giving food because they thought the child's “acting out” behaviors were related to hunger in some way (Fig. 1, quotation C1) versus the obese group, where food, and often an entire meal, was given because they could not “hold out” against the child's will and thought food would calm or appease them (quotations C2–3). Another behavior noted only in the overweight or obese groups was a child's preoccupation with food or the child asking for food “all the time” regardless of the last meal, often in association with descriptions of poor behavior (quotation C4).

Control

Many of the participants either described directly, or conveyed through their responses, degrees of emotional or physical control regarding their child's food choices and eating habits. Particularly in the parents of obese children, the lack of control emerged when describing food decisions, with the majority of participants expressing frustration and disbelief at their child's choices (Fig. 1, quotation D1). Though some parents of obese children did describe strategies for their child to make “better” food choices, this was most evident in the normal weight group. The parents of normal weight children offered choices to their children, and they often limited the selections to healthy foods, or only made healthy options accessible for the child (quotation D2). Parents who described a greater degree of organization seemed to have better control with respect to the food decisions made in the household (quotation D3). More often, the parents of obese children did not express such organizational skills and, more regularly, yielded to their child's preferences (quotation D4).

This idea of control was also evident when parents described when their child did not want to eat. The parents of normal weight children generally had a more laissez-faire approach to a child's refusal to eat (quotation D5), when compared to the parents of obese children, who struggled more with getting their child to eat what they believed was appropriate. Across groups, families expressed the importance of eating meals together, usually at a kitchen table. In all groups, there were exceptions to patterns; however, in the overweight and obese groups, these exceptions were described as almost routine occurrences.

Discussion

This is one of the first explorations of positive deviance methodology being applied to the problem of childhood obesity. A recent study in adults demonstrated success in reducing BMI using a positive deviance approach with an Internet-based forum.11 The major positive outlier findings we identified were: making healthy snacks available for the child to access at will; lower juice and higher yogurt consumption; greater internalization of reasons for behavior change; greater parental recognition of emotional eating; avoiding purchasing unhealthy snacks altogether; and greater organization and planning around meals and snacks.

The finding of increased yogurt consumption in the normal and overweight groups, compared to the obese group, raises the question of whether yogurt consumption is a marker for a healthier diet or is a potential modifier of weight status on its own. There are data suggesting that yogurt may offer a protective effect against obesity despite consumption of an obesogenic diet,20 with conflicting theories on the mechanism, potentially through alterations of the gut microbiome.20–22

The finding that parents of overweight and obese children misclassify their children as normal or even underweight has been found before.17,23,24 In studies of Hispanic populations, a general acceptance or even preference for heavier weight has been found,25–27 though 60% of the parents of obese children in our study wanted their child to be smaller. Factors associated with a lower ability of accurately classifying a child's weight are parental income, education, Hispanic ethnicity, and the age of the child being less than 4 years.28 Previous work in a multiethnic population showed that parents' perception of weight in early childhood was driven by how the child looked and appeared to function,29 consistent with our findings.

The description of a healthy child as active and happy is consistent with the described literature. In contrast to other studies, where weight was not associated with the idea of healthy,30–32 normal weight parents did associate excess weight and poor health in this study. Previous work either did not examine perceptions by weight status of the child30,32,33 or only examined parents of overweight or obese children.31 Genetics as a cause has been described before29; that this was only described by parents of obese children may reflect either a strong family history or a sense of hopelessness and lack of control. In Goodell and colleagues,29 the focus group data described a rejection of doctors' advice on early childhood weight status, rather than the absence of negative data, “the doctor never said anything,” observed in our study. One study of Hispanic mothers from both normal and overweight and obese children found that the provider's input was viewed as important, helping to identify weight issues before they are visually obvious.34

Instrumental (reward) and emotional feeding practices have been associated with higher risk of inappropriate weight gain and maladaptive feeding behaviors in early childhood35; our study had similar findings. Notably, one interventional study aimed at preventing early childhood obesity observed reductions in instrumental and emotional feeding practices.36

Parents of normal weight children describing an internal reaction to their personal experiences as their motivation for behavioral change is a novel finding. However, this observational finding is essentially what the emerging literature on using motivational interviewing describes.37–39 The fact that interventions using motivational interviewing have demonstrated efficacy makes this parallel finding in normal weight children all the more interesting. Confidence and self-efficacy of parents have been described in the literature as important for sustained behavior change in childhood obesity,40,41 but no study has identified or discussed the finding of intrinsic motivation in children.

The differences in emotional and physical control found between the normal and obese groups supports the current literature on parental control in obesity. Much of the current literature focuses on physical control, such as restrictive feeding practices and pressuring children to eat.42–45 In our study, the normal weight group described specific organizational strategies for providing healthy foods, which is not well documented in the literature. This idea of organization as contributing to parental control is similar to the concept of self-efficacy, in that parents who feel more efficacious are more likely to continue to invest time into those projects they feel good about.46,47 Self-efficacy has been applied to research in general parenting outcomes, but only one study in the current literature specifically addressed parenting efficacy as related to childhood obesity outcomes in children40; no study has focused on the preschool age group.

Limitations

An alternative definition of positive deviants would be parent-child dyads, where the child had been overweight or obese and then the parent implemented a strategy that allowed the child to return to normal weight. These children would be extreme outliers and difficult to find. We attempted to study a population at high risk for obesity; however, some of the subjects did not have all of these risk factors. On the other hand, our sensitivity analysis examining income did not significantly influence the results. Whereas the size of this pilot study was small, successful positive deviance strategies have been implemented using similarly sized studies.10,48 Limiting the study to those with English proficiency affects the external validity of this study.

Positive deviance, the idea of studying those who are doing well despite the risk factors has potential to generate sustainable, acceptable interventional strategies. We characterized practices and behaviors unique to healthy weight parent-child dyads; the next step will be testing these locally generated hypotheses in the surrounding community.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jill Fleuriet, PhD, for providing advice on the development of the questionnaire.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the leadership and staff of Harlingen Pediatric Associates and Tapangan Pediatrics, from which subjects were recruited. We acknowledge the excellent research staff led by Mr. Juan Reyna from the Clinical Research Unit; the research participants who welcomed the research team into their homes for the sake of improving health via research; and the support of the Regional Academic Health Center, led by Dean Leonel Vela.

The Research to Advance Community Health (ReACH) Center provided funding for this work. ReACH had no involvement in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Byron A Foster wrote the first draft of the manuscript and no one was paid to produce any part of this article.

The project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2 TR001118. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Piziak V, Morgan-Cox M, Tubbs J, et al. Elevated body mass index in Texas Head Start children: A result of heredity and economics. South Med J 2010;103:1219–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, et al. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: A systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 2008;9:474–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham SA, Kramer MR, Narayan KMV. Incidence of childhood obesity in the United States. N Engl J Med 2014;370:403–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(12):CD001871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer LA, et al. Hip-Hop to Health Jr. Obesity Prevention Effectiveness Trial: Postintervention results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:994–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, Van Horn L, et al. Hip-Hop to Health Jr. for Latino preschool children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1616–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barkin SL, Gesell SB, Po'e EK, et al. Culturally tailored, family-centered, behavioral obesity intervention for Latino-American preschool-aged children. Pediatrics 2012;130:445–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Kerner JF, et al. Methodologic challenges in disseminating evidence-based interventions to promote physical activity. Am J Prev Med 2006;31(4 Suppl):S24–S34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackintosh UA, Marsh DR, Schroeder DG. Sustained positive deviant child care practices and their effects on child growth in Viet Nam. Food Nutr Bull 2002;23(4 Suppl):18–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ndiaye M, Siekmans K, Haddad S, et al. Impact of a positive deviance approach to improve the effectiveness of an iron-supplementation program to control nutritional anemia among rural Senegalese pregnant women. Food Nutr Bull 2009;30:128–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraschnewski JL, Stuckey HL, Rovniak LS, et al. Efficacy of a weight-loss website based on positive deviance: A randomized trial. Am J Prev Med 2011;41:610–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marsh DR, Schroeder DG, Dearden KA, et al. The power of positive deviance. BMJ 2004;329:1177–1179. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. National Survey of Children's Health, 2012. Available at http://childhealthdata.org/learn/topics_questions/2011-12-nsch Last accessed December, 2014

- 14.Bickel G, Nord M PC. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security. Washington, DC: USDA, 2000. Available at www.fns.usda.gov/guide-measuring-household-food-security-revised-2000 Last accessed December, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford CN, Slining MM, Popkin BM. Trends in dietary intake among US 2- to 6-year-old children, 1989–2008. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113:35–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devaney B, Kalb L, Briefel R, et al. Feeding infants and toddlers study: Overview of the study design. J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104(1 Suppl 1):s8–s13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckstein KC, Mikhail LM, Ariza AJ, et al. Parents' perceptions of their child's weight and health. Pediatrics 2006;117:681–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods 2003;15:85–109 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savin-Baden M, Major C. Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice. Routledge: London; New York, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poutahidis T, Kleinewietfeld M, Smillie C, et al. Microbial reprogramming inhibits Western diet-associated obesity. PLoS One 2013;8:e68596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uyeno Y, Sekiguchi Y, Kamagata Y. Impact of consumption of probiotic lactobacilli-containing yogurt on microbial composition in human feces. Int J Food Microbiol 2008;122:16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arora T, Singh S, Sharma RK. Probiotics: Interaction with gut microbiome and antiobesity potential. Nutrition 2013;29:591–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayles B. Perceptions of childhood obesity on the Texas-Mexico border. Public Health Nurs 2010;27:320–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carnell S, Edwards C, Croker H, et al. Parental perceptions of overweight in 3–5 y olds. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:353–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaparro MP, Langellier BA, Kim LP, et al. Predictors of accurate maternal perception of their preschool child's weight status among Hispanic WIC participants. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:2026–2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guendelman S, Fernald LC, Neufeld LM, et al. Maternal perceptions of early childhood ideal body weight differ among Mexican-origin mothers residing in Mexico compared to California. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:222–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sosa ET. Mexican American mothers' perceptions of childhood obesity: A theory-guided systematic literature review. Health Educ Behav 2012;39:396–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang JS, Becerra K, Oda T, et al. Parental ability to discriminate the weight status of children: Results of a survey. Pediatrics 2007;120:e112–e119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodell LS, Pierce MB, Bravo CM, et al. Parental perceptions of overweight during early childhood. Qual Health Res 2008;18:1548–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crawford PB, Gosliner W, Anderson C, et al. Counseling Latina mothers of preschool children about weight issues: Suggestions for a new framework. J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104:387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rich SS, DiMarco NM, Huettig C, et al. Perceptions of health status and play activities in parents of overweight Hispanic toddlers and preschoolers. Fam Community Health 28:130–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallagher MR, Gill S, Reifsnider E. Child health promotion and protection among Mexican mothers. West J Nurs Res 2008;30:588–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindsay AC, Sussner KM, Greaney ML, et al. Latina mothers' beliefs and practices related to weight status, feeding, and the development of child overweight. Public Health Nurs 28:107–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guerrero AD, Slusser WM, Barreto PM, et al. Latina mothers' perceptions of healthcare professional weight assessments of preschool-aged children. Matern Child Health J 2011;15:1308–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, Massey R, et al. Maternal feeding practices predict weight gain and obesogenic eating behaviors in young children: A prospective study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Østbye T, Krause KM, Stroo M, et al. Parent-focused change to prevent obesity in preschoolers: Results from the KAN-DO study. Prev Med (Baltim) 2012;55:188–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stewart L, Chapple J, Hughes AR, et al. Parents' journey through treatment for their child's obesity: A qualitative study. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:35–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taveras EM, Gortmaker SL, Hohman KH, et al. Randomized controlled trial to improve primary care to prevent and manage childhood obesity: The High Five for Kids study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011;165:714–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong EM, Cheng MM. Effects of motivational interviewing to promote weight loss in obese children. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:2519–2530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marvicsin D, Danford CA. Parenting efficacy related to childhood obesity: Comparison of parent and child perceptions. J Pediatr Nurs 2013;28:422–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arsenault LN, Xu K, Taveras EM, et al. Parents' obesity-related behavior and confidence to support behavioral change in their obese child: Data from the STAR study. Acad Pediatr 2014;14:456–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearson N, Biddle SJH, Gorely T. Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:267–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rifas-Shiman SL, Sherry B, Scanlon K, et al. Does maternal feeding restriction lead to childhood obesity in a prospective cohort study? Arch Dis Child 2011;96:265–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dev DA, McBride BA, Fiese BH, et al. Risk factors for overweight/obesity in preschool children: An ecological approach. Child Obes 2013;9:399–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonneville KR, Rifas-Shiman SL, Haines J, et al. Associations of parental control of feeding with eating in the absence of hunger and food sneaking, hiding, and hoarding. Child Obes 2013;9:346–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. W.H. Freeman: New York, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grossklaus H, Marvicsin D. Parenting efficacy and its relationship to the prevention of childhood obesity. Pediatr Nurs 2014;40:69–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marsh DR, Pachón H, Schroeder DG, et al. Design of a prospective, randomized evaluation of an integrated nutrition program in rural Viet Nam. Food Nutr Bull 2002;23(4 Suppl):36–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.