Abstract

Rationale

Having a family history of substance use disorders (FH+) increases risk for developing a substance use disorder. This risk may be at least partially mediated by increased exposure to childhood stressors among FH+ individuals. However, measures typically used to assess exposure to stressors are narrow in scope and vary across studies. The nature of stressors that disproportionately affect FH+ children, and how these stressors relate to later substance use in this population, are not well understood.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to assess exposure to a broad range of stressors among FH+ and FH− children to better characterize how exposure to childhood stressors relates to increased risk for substance misuse among FH+ individuals.

Methods

A total of 386 children (305 FH+, 81 FH−; ages 10-12) were assessed using the Stressful Life Events Schedule prior to the onset of regular substance use. Both the number and severity of stressors were compared. Preliminary follow-up analyses were done for 53 adolescents who subsequently reported initiation of substance use.

Results

FH+ children reported more frequent and severe stressors than did FH− children, specifically in the areas of housing, family, school, crime, peers, and finances. Additionally, risk for substance use initiation during early adolescence was influenced directly by having a family history of substance use disorders and also indirectly through increased exposure to stressors among FH+ individuals.

Conclusions

FH+ children experience greater stress across multiple domains, which contributes to their risk for substance misuse and related problems during adolescence and young adulthood.

Keywords: Children, Family History, Substance Use, Risk, Stress

Individuals with a family history of substance use disorders (FH+) have a two to eightfold increase in risk for developing their own problems with substance use, relative to those with no such histories (FH−; Sher, Grekin, & Williams, 2004; Sher & Trull, 1994; Tarter et al., 2003). This increased risk is at least partly due to inherited vulnerabilities for substance abuse, including greater impulsivity, externalizing disorders, and antisocial traits (Andrews et al., 2011; Caspi, Moffitt, Newman, & Silva, 1996; Hicks, Iacono, & McGue, 2012; Pihl, Peterson, & Finn, 1990; Sher, Walitzer, Wood, & Brent, 1991; Tarter, 1988). However, FH+ individuals also report increased exposure to childhood stressors and adversity, which are linked to the development of substance use disorders in the general population (for review, see Enoch, 2011). As such, there is a need to comprehensively assess differences in exposure to childhood stressors based on family history of substance use disorders, and to examine the association between childhood stressors and substance use in FH+ individuals.

Much of the research documenting increased exposure to childhood stressors among FH+ individuals has focused on severe childhood stressors. A large epidemiological study of middle-aged and older adults found that those with at least one alcohol-abusing parent reported higher rates of childhood stressors including physical and sexual abuse, domestic violence, parental divorce, suicide attempts by family members, and exposure to criminal behavior (Anda et al., 2002). A similar national study found that adults with a family history of alcohol use disorders were more likely to endorse each of four major childhood stressors: parental divorce, parental death, living with foster parents, and living in an institution (Pilowsky, Keyes, & Hasin, 2009). These studies indicate FH+ individuals are at greater risk for experiencing relatively serious and traumatic stressors during childhood.

There is also evidence that FH+ individuals have increased exposure to more moderate and chronic stressors during childhood. Young adults with an alcohol-abusing parent are more likely to report childhood stressors related to their parent's behavior, such as criminality and actions causing public embarrassment (Menees & Segrin, 2000; Sher, Gershuny, Peterson, & Raskin, 1997). Another study focused on recent stressors found youth with alcohol-abusing parents were more likely to report significant academic problems, major changes in the composition of their household, and family financial problems during the previous year (Hussong et al., 2008). Collectively, these results suggest increased exposure to stressors across a broad range of life areas among FH+ individuals, and raise questions about how this exposure may contribute to the development of substance use disorders.

Previous research linking childhood stress exposure and increased risk for substance use disorders in FH+ individuals has had three main limitations: (1) large temporal gaps between stressful events and the stress assessment, (2) limited scope of stressors assessed, and (3) limited assessment of stress severity. These limitations are noteworthy for several reasons. First, a significant temporal gap between experiencing stressful events and the stress assessment can greatly limit the accuracy of assessment measures. Many studies assess childhood stressors retrospectively in middle or later adulthood (e.g., Anda, Croft, Felitti, & et al., 1999; Felitti et al., 1998). These studies are subject to significant measurement error, including recall biases and frequent false negative ratings (Hardt & Rutter, 2004; Susser & Widom, 2012) that may obscure associations between stressors and outcomes (Raphael, Widom, & Lange, 2001; Widom, Weiler, & Cottler, 1999).

Second, all but one of the studies described above have relied on checklist assessments of a narrow set of events; these have varied across studies and only provide a total number of stressful events experienced. Several of these stressful event checklists include only serious traumas (e.g., Anda et al., 2002; Pilowsky, Keyes, & Hasin, 2009) or stressors related to a single domain such as family relationship problems (e.g., Menees & Segrin, 2000). A study by Sher and colleagues (1997) includes a broader range of potential stressors, with 50 items, although many of the items relate to family problems and being abused. These studies provide indications of increased exposure to stressors during childhood among FH+ individuals, but the scope and magnitude of this exposure is not clear. No research to date has comprehensively examined self-reported cumulative exposure to stressors in FH+ and FH− children by including serious traumas (e.g., abuse), chronic problems (e.g., relationship dysfunction), and more moderate stressors (e.g., academic difficulties) in one assessment.

Finally, stressor severity is an important factor because some stressors have larger effects than others. There is limited research examining stressor severity in FH+ individuals, but one study found that FH+ young adults rate their childhood stressors as more severe than do individuals without substance-abusing parents (Hussong et al., 2008). However, subjective ratings are influenced by multiple variables that increase the potential for biased reporting, including age, education, attachment style, personality traits, mood, and psychiatric diagnoses (Almeida, 2005; Dohrenwend, 2006; Maunder, Lancee, Nolan, Hunter, & Tannenbaum, 2006; Watson, 1988). To avoid potential participant biases in subjective reports of stressor severity, procedures have recently been developed to objectively assess stressor severity (Carter & Garber, 2011; Gershon et al., 2011). In these studies, trained interviewers obtain detailed information about exposure to specific stressors, which is then scored by several raters trained to determine the objective severity of the event. One such measure is the Stressful Life Events Schedule (SLES; Williamson et al., 2003), a standardized semi-structured interview that quantifies the date, duration, description, severity, and total number of stressors that an individual reports. This measure was designed for use in children and adolescents and includes a broad range of stressors, allowing measurement of both relatively normative experiences (e.g., academic difficulties, peer conflicts) and more serious adverse events (e.g., child abuse, domestic violence in the home).

The purpose of the present study was to quantify the types and severity of lifetime stressors experienced by 10− to 12-year-old FH+ and FH− children by comparing them on a range of moderate and more severe stressors. It was hypothesized that FH+ children would report more stressors overall, and increased stressors in specific areas (e.g., family relationships), relative to FH− children. Additionally, it was hypothesized that the severity of stressors reported by FH+ children would be greater than that reported by FH− children. Finally, exploratory path analysis using preliminary data on substance use initiation in this sample were performed to examine prospective associations between family history, childhood stressor severity, and the initiation of substance use.

Methods

Participants

Participants consisted of 305 children with a family history of a substance use disorder (FH+) and 81 children with no parents or grandparents with a substance use disorder (FH−). Children and their parents were recruited from the community through radio, online, and television advertisements into a longitudinal study on the development of substance use and impulse control across adolescence. This ongoing study includes an assessment at study entry (age 10-12) and biannual follow-ups. A small number of participants (6.1% of FH−, 1.6% of FH+) did not return for any follow-up appointments. The median length of follow-up for the remainder of the sample is 24.5 months, with a maximum of 36 months. One parent or guardian participated with each child. Information about demographic characteristics, family history of substance use disorders, psychiatric disorders, and stressors was collected at study entry. FH+ children were oversampled so that a high proportion of the sample was at increased risk for developing substance misuse. The Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio approved the study procedures. Participant data were further protected by a Certificate of Confidentiality from the Department of Health and Human Services.

Group demographics were compared using Mann-Whitney U-tests and are presented in Table 1. For a detailed description of this sample, refer to Ryan et al. (Under Review). Briefly, the average age of the children at study entry was 11 years, they were of average IQ, and were predominantly Hispanic. The groups did not differ in age, sex ratios, or ethnicity, although FH+ children had lower SES (U(384) = 8117.5, Z = 4.75, p< .001) and lower IQs (U(384) = 6007.5, Z = 7.11, p< .001) than did FH− children. Participants also varied in psychiatric diagnoses. No FH− child met lifetime criteria for any externalizing or internalizing disorder, but some children in the FH+ group met criteria for current psychiatric disorders. Anxiety disorders and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) were the most common diagnoses, with nearly 20% of FH+ children having an anxiety disorder and nearly 30% having ADHD. Very few children from either group reported ever using alcohol or other drugs at study entry and only 2 children were excluded for being regular substance users.

Table 1.

Demographic and psychiatric details of the sample

| FH− (n=81) | FH+ (n=305) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age | 11.1 (.8) | 11.0 (.8) |

| Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence | 102.3 (12.2) | 94.8 (11.3)* |

| Four Factor Index of Socioeconomic Status | 43.5 (10.8) | 32.2 (11.4)* |

| Number (%) | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Boys | 35 (43.2) | 152 (49.8) |

| Girls | 46 (56.8) | 153 (50.2) |

| Ethnicity n(%) | ||

| White/Caucasian | 18 (22.2) | 33 (10.8) |

| Black/African-American | 4 (4.9) | 25 (8.2) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 57 (70.4) | 247 (81.0) |

| Multiethnic | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) |

| Current Psychiatric Disorders | ||

| Internalizing Disorders | ||

| Anxiety Disorder | 0 (0) | 57 (18.7) |

| Dysthymia | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Externalizing Disorders | ||

| ADHD | 0 (0) | 90 (29.5) |

| ODD | 0 (0) | 29 (9.5) |

| DBD NOS | 0 (0) | 18 (5.9) |

| Lifetime substance use at study entry | ||

| Alcohol | 2 (2.5) | 10 (3.3) |

| Marijuana | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Tobacco | 1 (12) | 5 (1.6) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Note. Diagnosis totals for FH group do not equal total n for group due to children with multiple diagnoses

p < .001.

FH+, children with a family history of substance use; FH−, children without a family history of substance use. ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; DBD, disruptive behavior disorder; NOS, not otherwise specified; ODD, Oppositional Defiant Disorder.

Psychiatric diagnoses among parents and grandparents were not exclusionary for either group. In this sample, 22.3% of FH+ parents had a mood disorder and less than 0.5% had a psychotic disorder. Among FH− parents, 2.5% had a mood disorder and 0.6% had a psychotic disorder. Among grandparents, 9.2% of FH+ grandparents had a psychiatric diagnosis (mood disorder: 8.7% ; psychotic disorder: 0.5%) and 1.9% of FH− grandparents had a psychiatric diagnosis (all mood disorders). Mood disorders were more common in FH+ parents (p < .001, Fisher's exact test) and FH+ grandparents (p < .001, Fisher's exact test). Psychotic disorders were more common in FH+ grandparents (p = .03, Fisher's exact test), but did not differ between FH− and FH+ parents (p = .62, Fisher's exact test). No parents or grandparents in the FH− group had a substance use disorder, but 100% of fathers, 28.9% of mothers, and 35.6% of grandparents in the FH+ group had a substance use disorder.

Measures

Socioeconomic Status

The Four Factor Index of Socioeconomic Status (FFISS; Hollingshead, 1975) quantifies the socioeconomic status of a family based on caregiver education, occupation, and marital status. Education scores range from 1 (less than seventh grade) to 7 (graduate professional training), and Occupation codes ranged from 1 (farm laborers/menial service workers) to 9 (higher executives and major professionals). Each family's score is computed by multiplying the Occupation value by 5 and the Education scale value by 3 and summing the products. Hollingshead Index scores range from 8 to 66, with higher scores reflecting higher SES. This instrument has good inter-rater reliability (κ = .68) and agreement with other measures of socioeconomic status (e.g., r = ..81-.86; Cirino et al., 2002).

Intelligence

The Wechsler Abbreviated Intelligence Scale (WASI; The Psychological Corporation, 1999) is a brief standardized measure of general intelligence designed for use with children and adults between the ages of 6 and 89 years. The full battery consists of four subtests and can be adminstered in 30 minutes. The Vocabulary and Similarities subtests combine to measure verbal–crystallized abilities, and Block Design and Matrix Reasoning combine to measure nonverbal–fluid abilities. IQ scores are scaled in traditional IQ standard score units (M = 100, SD = 15). The WASI has excellent internal consistency (α = .92 to .94 for each subtest) and test-retest reliability (.88 to .93 for IQ scores in children; The Psychological Corporation, 1999). It also correlates highly with other tests of intelligence (e.g., r = .89; Hays, Reas, & Shaw, 2002).

Psychiatric Diagnoses

The Kiddie and Young Adult Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders Schedule, Present State and Lifetime (K-SADS; Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, Rao, Flynn, Moreci et al., 1997) is designed to assess Axis I diagnoses in children and adolescents. The K-SADS is a semi-structured clinical interview with good inter-rater reliability (.93 to 1.00), test-retest reliability (κ = 63 to 1.00, depending on diagnosis), and concurrent validity with other measures of psychological functioning.

The Family History Assessment Module (FHAM; Janca, Bucholz, Janca, & Jabos-Laster, 1991) is a semi-structured interview that assesses major psychiatric disorders (substance use disorders, mania, depression, antisocial personality, and schizophrenia) in relatives of the person being interviewed. In the current study, a parent was interviewed about psychiatric diagnoses in their child's parents, grandparents, and siblings. The FHAM has demonstrated excellent specificity (98%) and moderate sensitivity (45%) for alcohol and other drug use disorders in previous research (Rice et al., 1995).

Stress Exposure

The Stressful Life Events Schedule (SLES; Williamson et al., 2003) is a standardized, semi-structured interview that quantifies the date, duration, description, and perceived stress caused by a broad range of events occurring during the child's lifetime. The severity of reported stressors is rated by trained research staff using a standardized procedure (described in James et al., 2013). Briefly, the researcher who conducted the SLES interview met with a group of 3 additional team members trained in rating SLES events and reviewed each individual stressor aloud. Participants’ membership in the FH+ or FH− group was not identified during these meetings. Each rater provided a rating of stressor severity after hearing each event and comparing the content to criteria associated with each level of severity ranging from 1 (minimally stressful) to 4 (extremely stressful). If raters were not in agreement, the group came to a consensus about stressor severity by asking the interviewer to re-read parts of the event that led to deviation in scores. This was followed by a discussion among the group, and consulting with training material or the PI of the project if necessary. To calculate the cumulative severity of stressor exposure, objective severity ratings are squared, so that more severe ratings are more heavily weighted, and summed (Williamson et al., 2003).

The training procedure used to prepare research team members to administer and rate the SLES included several steps. First, trainees learned about the development and use of the SLES through discussion with expert raters and reading the measure's manual. Second, they observed expert raters administer the semi-structured interviews. Third, trainees joined consensus meetings (desribed above) and shared their ratings of the events from the observed interviews prior to hearing others’ ratings. Experienced raters then provded feedback on the trainee's ratings. Finally, trainees practiced administration of the SLES interview under observation by expert raters. To ensure the continued quality of ratings obtained from consensus meetings over the course of the study, expert raters from outside the research team periodically joined consensus meetings to observe the accuracy of ratings.

Screening and Study Procedures

Prior to study entry, basic demographic information was reported by parents and socioeconomic status was assessed using the Four Factor Index of Socioeconomic Status (Hollingshead, 1975). Children were evaluated for current psychiatric disorders using the Kiddie and Young Adult Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders Schedule, Present State and Lifetime (K-SADS; Kaufman et al., 1997). Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorder and ADHD, Dysthymia, and Anxiety Disorders were not exclusionary for the FH+ group because these disorders are commonly co-morbid with substance use involvement (Iacono, Malone, & McGue, 2008). Exclusion criteria were: regular substance use by the child (defined as use at least once per month for 6 consecutive months; Clark, Cornelius, Kirisci, & Tarter, 2005); positive urine drug test at time of screening; low IQ (< 70); or physical/developmental disabilities that would interfere with the ability to understand or complete study procedures. Families were classified as FH+ and FH− based on parent responses regarding substance abuse issues in first- and second-degree relatives on the Family History Assessment Module (FHAM; Janca, Bucholz, Janca, & Jabos-Laster, 1991). All FH+ participants had a biological father with a past or present substance use disorder; additional diagnoses in parents or other relatives were not exclusionary. The parent/caregiver informants for this study included biological fathers (13.7%), biological mothers (85%) and other relatives (1.3%). Parental substance use disorder diagnoses were established through interviews with the affected parent (27.2%), the other parent (71.1%) or another family member (1.7%). Interviews were conducted by trained bachelors and graduate-level interviewers supervised by a board-certified child psychiatrist.

Approximately two weeks after qualifying into the study, participants arrived for their initial study visit between 8:30-9:00 a.m. and both parents and children provided breath and urine samples for alcohol and other drug screening. During this visit and subsequent biannual study visits, parents and children were placed in separate sound-attenuated testing rooms to complete a battery of self-report, interview, and behavioral measures.

Stressors

Children were interviewed at study entry about the occurrence of stressful life events during their lifetime using the Stressful Life Events Schedule (SLES; Williamson et al., 2003). Stressors were grouped, based on the type of event, into 10 categories: 1) Abuse (e.g., “Has anyone physically abused you?”); 2) Housing (e.g., “Have you changed residences?”); 3) Family (e.g., “Have your parents had any problems getting along?”); 4) School (e.g., “Have you had any difficulties with your performance at school, such as failing finals, classes, or grades and/or receiving deficiency reports or letters about your poor performance?”); 5) Crime (e.g., “Were any close friends and/or family members caught committing any crimes?”); 6) Medical (e.g., “Were you hospitalized or did you have surgery?”); 7) Peers (e.g., “Have you had problems being accepted by your peers?”); 8) Deaths (e.g., “Has anyone in your immediate family passed away [parents, brothers, or sisters])?”; 9) Money (e.g., “Was a parent fired, dismissed, or laid off from his/her job?”); and 10) Other (e.g., “Have you revealed to anyone that you are bisexual/homosexual?”, “Have you lost a pet or has your pet died or run away?”, “Have you received any unexpected bad news?”, and “Have you had to break any bad news to someone, which was not about your relationship with him/her?”). Overall cumulative severity ratings and ratings for each category of stressor were compared.

Substance Use

Upon arrival for all study visits, adolescents provided breath and urine samples to test for recent use of alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, benzodiazepines, opiates, or amphetamines. No adolescent tested positive at screening or the initial study visit. Breath samples were tested using the AlcoTest® 7110 MKIII C device (Draeger Safety Inc., Durango, CO). Urine was tested using the Panel/Dip Drugs of Abuse Testing Device (Redwood Biotech, Santa Rosa, CA). Adolescents were also interviewed using a drug history questionnaire, which assesses patterns of use for a number of licit and illicit drugs. These data were self-reported and answers were not shared with the parent/legal guardian. Adolescent self-report was the primary measure used to determine substance use; when breath/urine tests indicated substance use but no use was self-reported, participants were informed of their drug test results and re-interviewed regarding their substance use. Either self-reported drug use or a positive urine/breath test was sufficient to indicate substance use initiation.

Analyses

The total number of child-reported stressful life events and frequencies of children reporting events in each category at study entry were compared using Mann-Whitney U-tests and chi-square tests, respectively. Nonparametric tests were chosen because study variables were not normally distributed. To examine the relative severity of stressors reported by each group, the total stress severity ratings for each category also were compared using Mann-Whitney U-tests. Children who reported at least one stressor in a category were included in the analysis for that category. Stressor severity ratings across all categories were also compared in participants who initiated substance use at early ages (< 15 years) and those who did not, using Mann-Whitney U-tests. Finally, we used a path analysis to detect whether cumulative stressor severity reported at study entry mediates the association between family history of substance use disorders and substance use initiation during early adolescence. In our path analysis, two regression models were fitted. In the first model, a multiple linear regression model was used with stressor severity as the response variable and family history (binary), child sex, presence of a psychiatric diagnosis in the child (binary) and parents (binary), child IQ, and family socioeconomic status as the explanatory variables. In the second model, a multiple logistic regression model was used with being a substance user or non-user (binary variable) as the response variable and stressor severity and all explanatory variables in model 1 as the predictors. This analysis allowed us to control for the effects of demographic variables on the association among family history, childhood stressor severity, and substance use initiation. Path analysis was performed using Mplus (Version 7.11) and maximum likelihood estimation for all models.

Results

Group Differences in Stressors

Cumulative stress severity ratings at study entry were significantly higher for FH+ children than for FH− children, indicating FH+ children experienced greater lifetime exposure to stressors by age 10 to 12 than did FH− children. When the categories of stressors were examined individually, many stressors were fairly common in the sample. Chi-square tests revealed that more FH+ children reported stressors in the categories of Housing, Family, School, Crime, Peers, and Money than did FH− children (see Table 2, left panel for details). There were no group differences in the rates of children reporting stressors in the areas of Abuse, Medical, Deaths, or Other stressors. The severity of stressors experienced by each group is also reported in Table 2 (right panel). FH+ children experienced more cumulative stressor exposure in the areas of Housing, Family, School, and Money did FH− children.

Table 2.

Stressful life events in each group of children

| Types of stress | Prevalence of stressors (%) | Severity of stressors, M (SD) | Effect size (d) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FH− | FH+ | FH− | FH+ | ||

| Abuse | 1.2 | 3.3 | 9.0 (N/A) | 15.0 (14.7) | .58 |

| Housing | 60.5 | 78.0** | 4.2 (3.6) | 5.9 (5.5)* | .36 |

| Family | 82.7 | 92.1* | 4.9 (4.5) | 9.1 (8.4)** | .62 |

| School | 84 | 93.8* | 4.3 (3.3) | 6.4 (5.2)** | .48 |

| Crime | 19.8 | 45.6** | 5.6 (8.8) | 6.8 (7.4) | .15 |

| Health | 85.2 | 83.6 | 7.4 (6.3) | 7.7 (7.4) | .04 |

| Peer | 46.9 | 63.9** | 5.0 (4.1) | 6.4 (6.1) | .27 |

| Death | 49.4 | 59.3 | 7.3 (4.9) | 8.2 (5.7) | .17 |

| Money | 37.0 | 55.7* | 2.3 (1.8) | 3.5 (2.6)** | .54 |

| Other | 70.4 | 69.8 | 6.3 (5.1) | 7.7 (6.4) | .24 |

| Total number of stressors M (SD) | Total severity of stressors M (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.7 (6.4) | 16.4 (8.1)** | 28.0 (19.4) | 43.2 (27.6)** | .63 | |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01.

Total FH− n =81, total FH+ n=305, stress severity per category columns contains data only from those individuals reporting at least 1 event in that category. FH+, children with a family history of substance use; FH−, children without a family history of substance use.

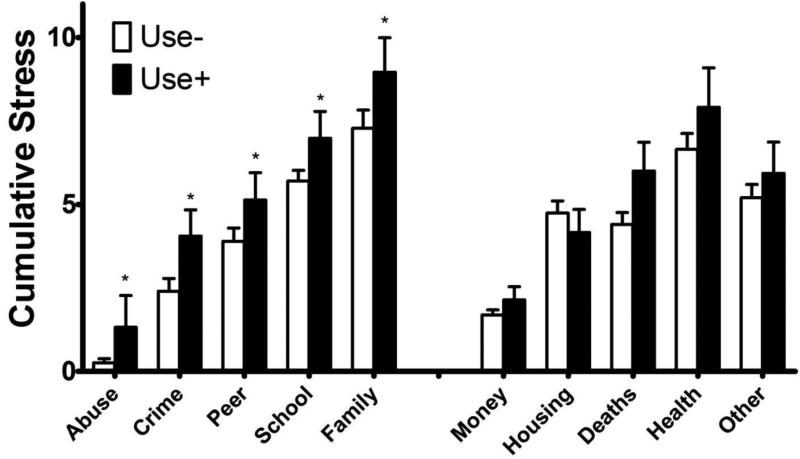

Relations between stressors and substance use in early adolescence

Fifty FH+ adolescents (27 girls, 23 boys) and three FH− adolescents (3 girls) initiated alcohol and/or drug use during the follow-up period. The timing of initiation varied across participants (e.g., 18.9% reported use at 6-month follow-up; 24.5% at 12-month, 24.5% at 18-month, 5.7% at 24-month, 18.9% at 30-month, and 7.5% at 36-month). The mean age of initiation was 13.3 years. The 53 adolescents who initiated substance use were then compared with the remainder of the sample who had not yet initiated substance use (n = 318; 159 girls, 159 boys). The fifteen children who had initiated substance use prior to study entry were excluded from this analysis. The groups were compared on both cumulative severity of stressors and the prevalence of stressors in different domains using Mann-Whitney U-tests. Briefly, adolescents with early onset substance use reported more cumulative stressors at study entry, as well as more exposure to stressors in the areas of Abuse, Family, School, Crime, and Peers (Figure 1). Substance users did not differ from non-users on IQ, family socioeconomic status, proportion of males and females, or ethnic makeup. Additionally, rates of psychiatric diagnoses among adolescents and their relatives, including the prevalence of substance use disorders in the families of FH+ participants, did not differ between users and non-users.

Figure 1.

Cumulative stress severity in different domains among children with (black bars) and without (white bars) early-onset substance use. * = p < .05

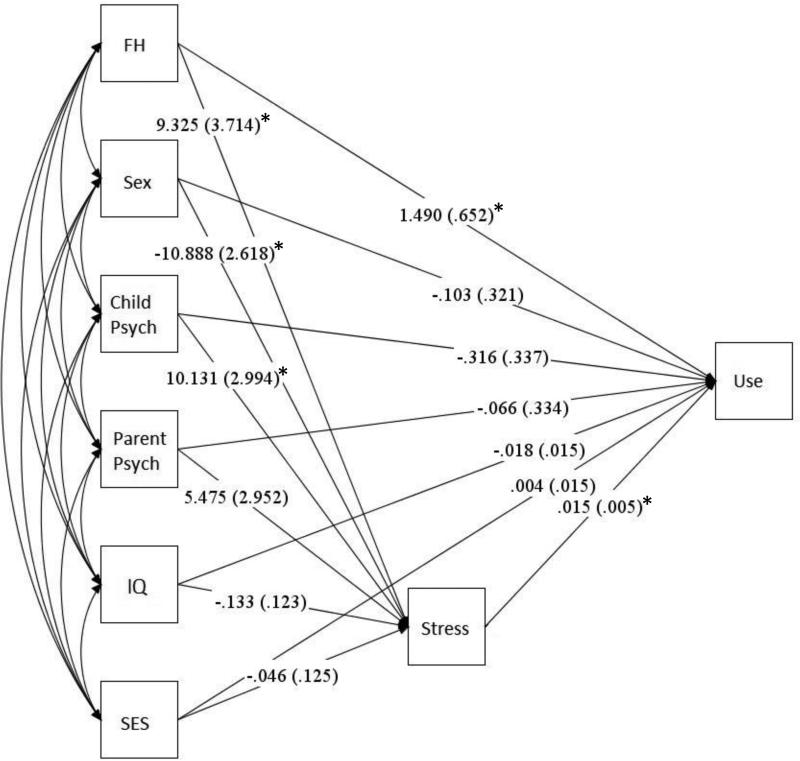

Parameter estimates (SE) from path analysis are shown in Figure 2. Family history, child sex, and child diagnosis were significantly related to cumulative stressor severity reported at study entry, and both stressor severity and family history were significantly related to substance use initiation during early adolescence. No interaction terms were significantly related to substance use initiation, and therefore they were not retained in the model. After controlling for other variables, FH+ adolescents’ stressor severity was 9.33 points higher than it was for FH− adolescents (p=0.012). Additionally, FH+ adolescents were 4 times more likely than FH− adolescents to initiate substance use (OR=4.44, p=0.022) and every 10-point increase in the stressor severity at study entry increases the odds of substance use initiation during early adolescence by 16% (p=0.006).

Figure 2.

Path diagram depicting associations among family history of substance use disorders, cumulative stressor severity reported at baseline, and substance use initiation during early adolescence. FH, child sex, and child psychiatric diagnosis are significantly related to cumulative stressor severity reported at baseline. Stressor severity and FH are also significantly related to substance use initiation. No other pathways are significant.

Discussion

This study provides new evidence of increased exposure to childhood stressors across a broad range of life events among children with family histories of substance use disorders (FH+), relative to peers with no family history of substance use disorders (FH−). FH+ children reported more total stressors, and more stressors in the areas of Housing, Family, School, Crime, Peers, and Money. Furthermore, the weighted cumulative severity of stressors reported in the areas of Housing, Family, School, and Money were greater for FH+ children than for FH− children. These results suggest the environments of FH+ children not only include increased overall exposure to stressors, but also that it is concentrated in certain domains. These results suggest that FH+ status and exposure to stressors are both related to substance use initiation, and greater exposure to stressors among FH+ youth creates an additive effect that increases risk for substance use disorders in this group. FH− adolescents with high exposure to stressors may be equally at risk (although it is worth noting that FH− adolescents in our sample were less likely to have experienced high exposure to stressors). However, this conclusion is tentative given the low number of FH-adolescents who initiated substance use in the present sample. We will continue to examine relationships between exposure to stressors and the initiation and progression of substance use disorders as part of our ongoing longitudinal studies.

The results presented in this study extend the current research literature in three important ways. First, the comprehensive assessment of both serious and more moderate childhood stressors extends on previous research that has focused primarily on very stressful or traumatic childhood events, such as being abused (e.g., Anda et al., 2002; Dube et al., 2001; Pilowsky, Keyes, & Hasin, 2009) and demonstrates the breadth of areas in which exposure to stressors is increased among FH+ youth. Second, the current study extends previous research in which adults have retrospectively reported exposure to childhood stressors (e.g., Anda, et al., 1999; Felitti et al., 1998). By interviewing FH+ individuals during childhood, this study avoids concerns about the accuracy of retrospective reports of childhood stressors (e.g., Hardt & Rutter, 2004; Susser & Widom, 2012; Raphael, Widom, & Lange, 2001; Widom, Weiler, & Cottler, 1999). Third, this study extends research using checklist methods that assess the presence or absence of different childhood stressors by including a measure of the objective severity of stressors. FH+ young adults subjectively rate their childhood stressors as more severe than do FH− individuals (Hussong et al., 2008). However, subjective measures of stressor severity can be influenced by a number of factors (Almeida, 2005; Dohrenwend, 2006; Maunder, Lancee, Nolan, Hunter, & Tannenbaum, 2006; Watson, 1988), so the current study clarifies whether there is a difference in perception or actual experience of stressors in FH+ vs. FH− individuals. Taken together, the results of this research improve our understanding of the increased exposure to stressors among FH+ individuals and provide compelling evidence that exposure to stressors may contribute to the increased risk for substance use disorders in FH+ individuals.

In addition to increasing understanding of exposure to childhood stressors among FH+ individuals, the examination of specific types of stressors in this study suggests some mechanisms through which a parental substance use disorder could increase a child's exposure to stressors. For example, the types of stressors categorized as Family (e.g., “Have your parents had any problems getting along?”), Crime (e.g., “Were any close friends and/or family members caught committing any crimes?”), and Money (e.g., “Was a parent fired, dismissed, or laid off from his/her job?”) are common among adults with substance use disorders and reflected in the diagnostic criteria for Substance Abuse in DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Therefore, it is not surprising that these types of stressors are more frequently reported by children of individuals with substance use disorders. Similarly, the stressors categorized as Housing included high rates of changing residences and having different people living in one's household, which may indirectly result from parental substance misuse through problems with finances and/or relationships. However, FH+ children also reported higher rates of School and Peer stressors, indicating they experienced increased problems outside the home as well. Knowing specific areas in which FH+ children experience increased stressors can improve measurement of stressors in future research of this type, and could be used to target interventions for FH+ youth.

The greater exposure to stressors among FH+ youth is especially concerning, given that FH+ youth may be particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of stressors because of the increased incidence of the “behavioral undercontrol” phenotype (e.g., sensation seeking, risk-taking, aggressiveness, and antisocial behaviors) in this group (Sher et al., 2004; Sher & Trull, 1994; Tarter et al., 2003). Reciprocal relationships have been noted between exposure to stressors and behavior problems during adolescence, such that children with externalizing tendencies are more likely to increase these behaviors following stressors. In turn, increased behavior problems and risk-taking early in life, including substance misuse, can increase exposure to stressors over time (Kim, Conger, Elder Jr, & Lorenz, 2003). This pattern may account for the finding that FH+ children are less likely to be resilient following maltreatment (Jaffee et al., 2007). Our preliminary results relating exposure to stressors in childhood to substance use during early adolescence suggest a prospective association between stressors and substance use among FH+ youth, although the reciprocal relationship between stressors and substance use merits further investigation. A similar relationship appears to be present among FH− children (however, note that there was a limited sample size of FH− users).

Preliminary results from participants who reported early-onset (< age 15) substance use include two important findings. First, the cumulative severity of all stressors experienced during childhood was increased among early-onset substance users. This is consistent with previous research relating retrospective assessments of early life to stress to substance use disorder (Enoch, 2011), and provides new evidence for a developmental pathway from childhood stress to early-onset substance use, which is an established risk factor for later substance use disorders (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012). Second, and similar to the results for FH+ and FH− children, early-onset substance users reported selective increases in stressors. Early-onset users had significantly greater cumulative stress related to Abuse, Family, School, Crime, and Peers. These differences parallel the family history group differences reported above, with the notable addition of a group difference for Abuse and no significant differences for Housing and Money. Thus, certain types of stressors may be particularly important for the development of early-onset substance use, and many of them also are more common among FH+ youth. Interventions to reduce the impact of stressors in those areas may have the greatest benefit. Additionally, these results are conceptually similar to research implicating specific types of stressors in the development of depression in adolescents with a family history of depression (Carter & Garber, 2011; Gershon et al., 2011), and further supports the notion that the impact of stressors on emotional and behavioral well-being may vary based on individual vulnerabilities.

This study included a large, well-characterized sample of FH+ children and a comprehensive assessment of their exposure to stressors. However, it is not without limitations. Specifically, diagnoses of substance use disorders in both parents were primarily made via interviews with mothers. The family history method of diagnosing substance use disorders in relatives is frequently used in research of this type (e.g., Sher, Gotham, Erickson, & Wood, 1996; Sher et al., 1991) because it is a cost-effective way to gain information about a large number of relatives, including those who are deceased, incarcerated, or otherwise unavailable. However, there is some evidence that informants underreport substance use disorder symptoms in family members using this measure (Andreasen et al., 1986). Thus, afflicted family members in the present study may have more extensive substance use problems than was indexed by our methodology. Additionally, the predominately Hispanic makeup of this sample may be viewed as a limitation as the results may not generalize to other ethnic groups. However, this is also a strength of this study, given that Hispanic individuals represent a large, and increasing, proportion of the U.S. population yet are underrepresented in research of this type. Finally, the ratings of stressor severity were created by trained raters using standardized procedures and coming to a consensus. Although every effort was made to ensure compliance with standard rating procedures for the SLES measure, interrater reliability in initial severity ratings, prior to arriving at a consensus, was not directly assessed in the present study. However, we have previously measured interrater reliability for SLES event severity in our laboratory using identical training methods and found good reliability (κ = .68; James et al., 2013).

In summary, this research demonstrates FH+ children experience greater stress than FH− children across a broad range of domains. Additionally, preliminary results indicate exposure to stressors in childhood prospectively predicts early-onset substance use. Our results suggest that both FH+ and FH− children who experience high levels of stress are at elevated risk for initiating substance use during early adolescence. Finally, the finding that many types of stressors associated with early-onset substance use were also increased among FH+ children suggests that environmental stressors may be a mechanism through which a family history of substance use disorders increases one's risk for developing substance misuse.

These findings have implications for clinical practice, as interventions such as enhancing adolescents’ coping skills could be tailored to reflect the most common areas of increased stress among FH+ youth. Additional research in this area will better characterize the stress and adversity experienced by FH+ youth. Ultimately, a more complete understanding of the stressors disproportionately experienced by FH+ children will be useful in designing prevention and early intervention efforts to reduce their risk for negative outcomes.

Acknowledgements

David Hernandez, Allison Ford, Marika Vela-Gude, Amanda Paley, Jessica Gutierrez-Barr, Anran Xu, James Newhouse, Susan McCorstin and Sharon Cates provided excellent technical assistance.

Role of Funding Source

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse under award numbers R01-DA026868; R01-DA033997; and T32-DA031115. The content is solely the view of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dougherty also gratefully acknowledges support from a research endowment, the William and Marguerite Wurzbach Distinguished Professorship.

Footnotes

Contributors

Author NE Charles managed literature searches and summaries of previous related work, completed statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

Author SR Ryan contributed to statistical analyses and manuscript revisions.

Authors DM Dougherty, CW Mathias, and A Acheson designed the study and wrote the protocol.

All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared

References

- Almeida DM. Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14(2):64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(17):1652–1658. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1652. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Chapman D, Edwards VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF. Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(8):1001–1009. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Rice J, Endicott J, Reich T, Coryell W. The family history approach to diagnosis: how useful is it? Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43(5):421–429. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800050019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews MM, Meda SA, Thomas AD, Potenza MN, Krystal JH, Worhunsky P, Pearlson GD. Individuals family history positive for alcoholism show functional magnetic resonance imaging differences in reward sensitivity that are related to impulsivity factors. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69(7):675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (4th ed.). Text revision American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carter JS, Garber J. Predictors of the first onset of a major depressive episode and changes in depressive symptoms across adolescence: stress and negative cognitions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(4):779. doi: 10.1037/a0025441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53(11):1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirino PT, Chin CE, Sevcik RA, Wolf M, Lovett M, Morris RD. Measuring socioeconomic status: reliability and preliminary validity for different approaches. Assessment. 2002;9:145–155. doi: 10.1177/10791102009002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Cornelius JR, Kirisci L, Tarter RE. Childhood risk categories for adolescent substance involvement: a general liability typology. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.008. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. Inventorying stressful life events as risk factors for psychopathology: Toward resolution of the problem of intracategory variability. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(3):477–495. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.477. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Croft JB, Edwards VJ, Giles WH. Growing up with parental alcohol abuse: exposure to childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25(12):1627–1640. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA. The role of early life stress as a predictor for alcohol and drug dependence. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214(1):17–31. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1916-6. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1916-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon A, Hayward C, Schraedley-Desmond P, Rudolph KD, Booster GD, Gotlib IH. Life stress and first onset of psychiatric disorders in daughters of depressed mothers. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45(7):855–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays JR, Reas DL, Shaw JB. Concurrent validity of the Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence and the Kaufman brief intelligence test among psychiatric inpatients. Psychological reports. 2002;90:355–359. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.90.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Index of the transmissible common liability to addiction: Heritability and prospective associations with substance abuse and related outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;123(Supplement 1)(0):S18–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.017. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. Department of Sociology, Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Bauer DJ, Huang W, Chassin L, Sher KJ, Zucker RA. Characterizing the life stressors of children of alcoholic parents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(6):819–832. doi: 10.1037/a0013704. doi: 10.1037/a0013704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: common and specific influences. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Polo-Tomas M, Taylor A. Individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguish resilient from non-resilient maltreated children: a cumulative stressors model. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(3):231–253. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.011. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LM, Mathias CW, Bray BC, Cates SE, Farris SJ, Dawes MA, Dougherty DM. Acquisition of rater agreement for the stressful life events schedule. Journal of Alcoholism and Drug Dependence. 2013 doi: 10.4172/2329-6488.1000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janca A, Bucholz KK, Janca MA, Jabos-Laster L. Family History Assessment Module. Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine; St. Louis, MO: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for affective sisorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Conger RD, Elder GH, Jr, Lorenz FO. Reciprocal influences between stressful life events and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development. 2003;74(1):127–143. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Nolan RP, Hunter JJ, Tannenbaum DW. The relationship of attachment insecurity to subjective stress and autonomic function during standardized acute stress in healthy adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;60(3):283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.08.013. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menees MM, Segrin C. The specificity of disrupted processes in families of adult children of alcoholics. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2000;35(4):361–367. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihl RO, Peterson J, Finn PR. Inherited predisposition to alcoholism: Characteristics of sons of male alcoholics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99(3):291–301. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.3.291. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.99.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Adverse childhood events and lifetime alcohol dependence. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(2) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael KG, Widom CS, Lange G. Childhood victimization and pain in adulthood: a prospective investigation. Pain. 2001;92(1–2):283–293. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00270-6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JP, Reich T, Bucholz KK, Neuman RJ, Fishman R, Rochberg N, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Jr., Schuckit MA, Begleiter H. Comparison of direct interview and family history diagnoses of alcohol dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19:1018–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan SR, Acheson A, Charles NE, Lake SL, Hernandez DL, Mathias CW, Dougherty DM. Clinical and social/environmental characteristics in a community sample of children with and without family histories of substance use disorder in the San Antonio area: A descriptive study. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2014.999202. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings, NSDUH Series H-45, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4725. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k11MH_FindingsandDetTables/2K11MHFR/NSDUHmhfr2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Susser E, Widom CS. Still searching for lost truths about the bitter sorrows of childhood. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2012;38:672–675. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs074. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gershuny BS, Peterson L, Raskin G. The role of childhood stressors in the intergenerational transmission of alcohol use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1997;58(4):414. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gotham HJ, Erickson DJ, Wood PK. A Prospective, High-Risk Study of the Relationship between Tobacco Dependence and Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1996;20(3):485–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Grekin ER, Williams NA. The development of alcohol use disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2004;22:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103(1):92–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susser E, Widom CS. Still searching for lost truths about the bitter sorrows of childhood. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;38(4):672–675. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs074. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE. Are there inherited behavioral traits that predispose to substance abuse? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(2):189–196. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.189. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Cornelius JR, Pajer K, Vanyukov M, Clark D. Neurobehavioral disinhibition in childhood predicts early age at onset of substance use disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1078–1085. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Psychological Corporation . WASI: Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence®. Harcourt Brace and Company; San Antonio, TX: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Intraindividual and interindividual analyses of positive and negative affect: Their relation to health complaints, perceived stress, and daily activities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1020–1030. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1020. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Weiler BL, Cottler LB. Childhood victimization and drug abuse: A comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67(6):867–880. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.867. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DE, Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Shiffrin TP, Lusky JA, Protopapa J, Brent DA. The stressful life events schedule for children and adolescents: development and validation. Psychiatry Research. 2003;119(3):225–241. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00134-3. doi: S0165178103001343 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]