Abstract

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is a classic gut hormone that is also expressed in the pancreatic islet, where it is highly up-regulated with obesity. Loss of CCK results in increased β-cell apoptosis in obese mice. Similarly, islet α-cells produce increased amounts of another gut peptide, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), in response to cytokine and nutrient stimulation. GLP-1 also protects β-cells from apoptosis via cAMP-mediated mechanisms. Therefore, we hypothesized that the activation of islet-derived CCK and GLP-1 may be linked. We show here that both human and mouse islets secrete active GLP-1 as a function of body mass index/obesity. Furthermore, GLP-1 can rapidly stimulate β-cell CCK production and secretion through direct targeting by the cAMP-modulated transcription factor, cAMP response element binding protein (CREB). We find that cAMP-mediated signaling is required for Cck expression, but CCK regulation by cAMP does not require stimulatory levels of glucose or insulin secretion. We also show that CREB directly targets the Cck promoter in islets from obese (Leptinob/ob) mice. Finally, we demonstrate that the ability of GLP-1 to protect β-cells from cytokine-induced apoptosis is partially dependent on CCK receptor signaling. Taken together, our work suggests that in obesity, active GLP-1 produced in the islet stimulates CCK production and secretion in a paracrine manner via cAMP and CREB. This intraislet incretin loop may be one mechanism whereby GLP-1 protects β-cells from apoptosis.

Finding ways to protect the insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells from apoptosis is of particular interest in the prevention of diabetes. Maintenance of β-cell mass is critical to provide adequate insulin production, especially in the setting of insulin resistance during obesity. In nondiabetic obesity, there is a compensatory increase in pancreatic β-cell mass (1). However, there is also increased islet stress due to the large demand for insulin production, which can lead to increased β-cell apoptosis (2). Maintaining a balance between β-cell regeneration and apoptosis is critical to prevent the onset of diabetes.

The hormone cholecystokinin (CCK) was first studied as a gastrointestinal peptide secreted by the small intestine in response to fat and protein intake (3). Although not classically defined as an incretin, CCK can function as an insulin secretagogue (4). CCK also induces satiety through actions in the brain, and has been studied as a therapeutic for obesity and diabetes. CCK signals through two G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), CCK A receptor (CCKAR) and CCK B receptor (5, 6). It was recently discovered that CCK is also expressed in the pancreatic islet, primarily in the β-cells, but only in an obese environment (7). Loss of CCK in obese mice results in decreased β-cell mass and increased β-cell death, leading to elevated fasting blood glucose (8), suggesting that CCK is critical for β-cell mass preservation in obesity. However, the mechanisms that underlie endogenous CCK regulation in the islet are unknown.

Previous studies have linked cAMP signaling to Cck expression in other tissues. cAMP response element (CRE) binding protein (CREB) binds to the Cck promoter in extracts from intestinal L cells and cells of neuronal origin (9–11). Likewise, in teratocarcinoma cells transient CREB overexpression increases Cck promoter activity, and activation of adenylate cyclase with forskolin stimulates Cck transcription that is dependent on CREB and the CRE in the Cck promoter (10). This indicates that Cck is likely directly regulated by cAMP and CREB in the gut and brain. Although the specific upstream modulators are unknown, we hypothesized that a similar mechanism of regulation occurs in the β-cell.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a hormone produced by intestinal L-cells and is well known for its role in promoting satiety and insulin secretion after a meal (12). As such, therapies that agonize the GLP-1 receptor (GLP1R) have become widespread for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. In addition to its role as an insulin secretagogue, GLP-1 protects β-cells from apoptosis. GLP-1 signals through a GPCR and activates cAMP production. Although multiple cAMP-mediated mechanisms are involved in apoptosis protection (13), it is not fully understood how GLP-1 protects β-cells from apoptosis. Because GLP-1 signals through cAMP/CREB pathways and has antiapoptotic action in the islet, we hypothesized that GLP-1 regulates β-cell CCK in obesity, and this could be a mechanism to protect islets from apoptosis.

We show here that both human and mouse islets secrete active GLP-1 as a function of body mass index (BMI)/obesity. GLP-1 stimulates β-cell Cck transcription and secretion through direct targeting by cAMP-stimulated CREB in both β-cells and islets from obese mice. This regulation is not dependent on glucose or insulin secretion. Finally, we find that CCK signaling is necessary for GLP-1-mediated protection of β-cells from apoptosis. Together, this work suggests that in the setting of obesity, an intraislet incretin pathway is activated where increased GLP-1 stimulates β-cell CCK production and signaling to protect β-cells from apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

Rat insulinoma cells (INS-1) were maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 11.1 mmol/L glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic. For low and physiological glucose experiments, media were replaced with fresh media containing 2.8 or 5.6 mmol/L glucose, respectively, for 1 hour before cAMP treatments. Islets were cultured in uncoated Petri dishes with RPMI 1640 containing 8 mmol/L glucose, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The 8-(4-chlorophenyl) thio-cyclic AMP [8-CPT-cAMP] was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences, active human GLP-1 (GLP-1 7–37) was from California Peptide Research, sulprostone was from Cayman Chemical, and proglumide sodium salt was from Tocris Bioscience.

Mice

Mice were housed in facilities with a standard light-dark cycle and fed ad libitum. Pancreatic islets were isolated essentially as described (14, 15) from 10- to 14-week-old male mice. All protocols were approved by the University of Wisconsin Animal Care and Use Committee to meet acceptable standards of humane animal care.

Human and mouse islet analysis

Human islets and islet/acinar pairs were obtained through the Integrated Islet Distribution Program. Islets were cultured overnight to confirm viability and sterility. Islets were then handpicked and cultured for an additional day before collection for assays. For analysis of islet secretion of GLP-1, human islets or freshly isolated mouse islets were incubated at a density of 1 islet per 10 μL of media. After incubation for 24 hours, media were collected and analyzed using an active GLP-1 ELISA (Millipore). To ensure that samples fell within the standard curve range, dilutions were made using the assay buffer included with the kit.

INS-1 secretion analysis

For CCK secretion analysis, INS-1 were plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells in each well of a 6-well dish approximately 24 hours before treatments. After GLP-1 or cAMP treatments, media were collected and analyzed by RIA to determine sulfated CCK levels (Alpco Diagnostics). Insulin secretion assays were performed in 96-well plates and measured using an in-house ELISA essentially as outlined in Ref. 16.

Cellular cAMP analysis

INS-1 cells were washed and preincubated in Krebs buffer containing 1.7mM glucose for 45 minutes. Cells were treated with Krebs buffer containing 11.1mM glucose in the presence or absence of 10nM sulprostone for 45 minutes. Cells were lysed in 0.1N HCl and assayed using the Cayman Chemical cAMP enzyme immunoassay kit and normalized to total protein.

Gene and protein expression analysis

RNA was isolated using either TRIzol or the QIAGEN RNeasy mini kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was prepared using monkey Moloney virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) then analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using Power SYBR Master Mix (Life Technologies). All transcripts were normalized to β-actin. Fold changes were calculated relative to vehicle only controls. Protein was isolated by lysing cells in a HEPES buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40 as well as protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentration was measured by bicinchoninic acid analysis, and 25 μg were run on an SDS-PAGE gel. Protein was transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane and nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation with tris-buffered saline with Tween 20/5% milk. Phospho-CREB (p-CREB) antibody (Cell Signaling Technologies) diluted 1:1000 in tris-buffered saline with Tween 20/5% milk was used to probe the membrane.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

INS-1 were cross-linked by incubation with 0.75% formaldehyde for 7 minutes at room temperature, then neutralized by the addition of glycine to a final concentration of 0.125M. Islets were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes before neutralization. ChIP experiments were carried out essentially as described (17). Approximately 1 × 107 INS-1 cells or approximately 300–400 islets were used per IP condition. For mouse islet experiments, islets from 1 or more mice were pooled together (total of 1000–1500 islets) for each biological replicate to account for multiple IP conditions (eg, control and test IPs) from a single replicate. Normal rabbit and mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc) were used as antibody controls. The RNA polymerase II antibody was from Covance (Clone MMS-126R), and the p-CREB (no. 4276) and CREB (no. 4820) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies. The antibody against p-CREB was discontinued during the course of these studies, necessitating the switch to a total CREB antibody for subsequent ChIP analysis. The antibody used for each experiment is described as p-CREB or CREB in the results section. Analysis of chromatin occupancy was carried out by qPCR using Power SYBR Master Mix (Life Technologies). Chromatin occupancy for each protein was calculated relative to input chromatin.

Apoptosis analysis

INS-1 were grown in tissue culture dishes or on sterile coverslips until approximately 75% confluency. Cells were pretreated with GLP-1 in the presence of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor (Millipore) for 1 hour, after which 10mM proglumide (DL-4-benzamido-N,N-di-n-propylglutaramic acid sodium salt) was added. Thirty minutes after proglumide addition, cells were treated with a cytokine cocktail containing 50-ng/mL mouse TNFα (Miltenyi Biotec), 10-ng/mL mouse IL-1β (Miltenyi Biotec), and 50 ng/mL mouse interferon-γ (Life Technologies). Cells were treated with cytokines/GLP-1/proglumide for a total of 24 hours, after which either protein was harvested for Western blotting or cells were fixed on coverslips with 4% paraformaldehyde. Apoptosis was measured using the DeadEnd Fluorometric terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling (TUNEL) system (Promega) and imaging was completed using an EVOS FL Auto fluorescence microscope (Life Technologies). ImageJ software (NIH) was used to count nuclei in at least 10 randomly chosen fields per treatment group for each replicate. Three biological replicates were performed.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using Prism (GraphPad) software and means ± SEM were plotted. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test as indicated in figure legends, with significance at P < .05.

Results

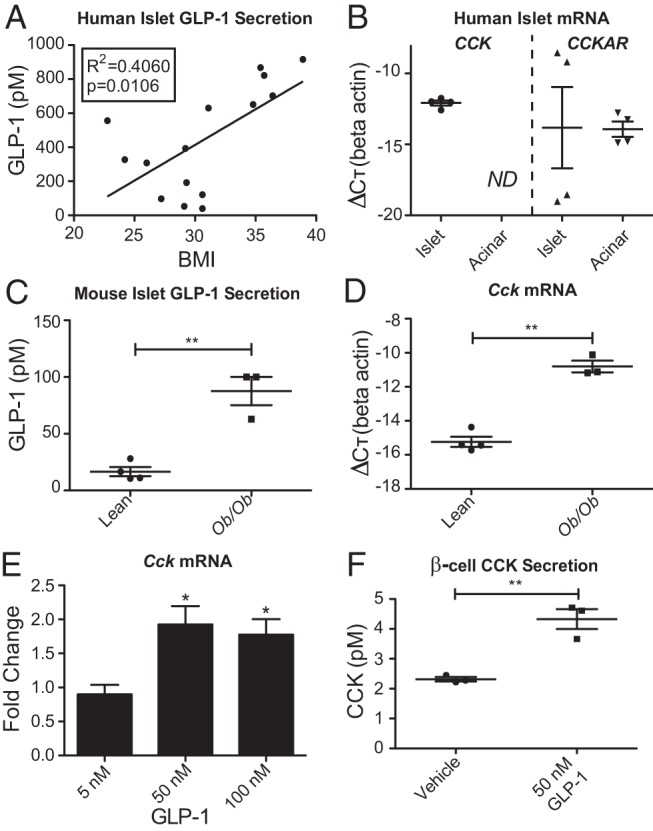

Human and mouse islets secrete active GLP-1 as a function of BMI/obesity

GLP-1 secretion from rodent and human pancreatic islets can be stimulated ex vivo by factors such as arginine, IL-6, and stress (18–21). Therefore, we wanted to determine whether human islet GLP-1 is similarly up-regulated in obesity. Islets received postmortem from 15 organ donors were analyzed ex vivo for their ability to secrete active GLP-1: GLP-1 (7–37) and GLP-1 (7–36) amide. Islets from nonobese individuals (BMI < 30) had relatively high basal levels of active GLP-1 secretion (275 ± 66pM), yet there is significantly more GLP-1 (594 ± 118pM, P = .04) secreted from islets of obese donors (BMI > 30). This suggests that islet-derived GLP-1 may function in response to obesity. Indeed, there is a correlation between human islet GLP-1 secretion and BMI of the donor (R2 = 0.406, P = .01) (Figure 1A). Human islets also express the CCK gene, whereas the transcript is not present in acinar tissue from the same donors (Figure 1B, left). In contrast, the CCKAR gene is expressed in acinar tissue, where it is known to be important in exocrine pancreatic function, whereas its expression in islet is highly variable (Figure 1B, right). Similar to human, islets from obese C57BL/6J mice with a leptin mutation (ob/ob mice) secrete significantly more GLP-1 than islets from lean controls (lean, 16.6 ± 4.1pM and ob/ob, 87.6 ± 12.4pM; P = .0016) (Figure 1C). These data demonstrate that pancreatic islet secretion of GLP-1 increases with nondiabetic obesity in both human and mouse, and human islets express the CCK gene.

Figure 1.

GLP-1 is secreted from nondiabetic obese human and mouse islets and stimulates β-cell CCK. A, Measurement of GLP-1 in conditioned media from human islets cultured over 24 hours. B, CCK/CCKAR gene expression in human islet/acinar tissue sets from 4 individual donors. ND, not detected. C, GLP-1 in conditioned media from mouse islets cultured over 24 hours. D, Cck gene expression in the same mouse islet samples for which GLP-1 secretion was measured. E, Cck gene expression in INS-1 β-cells treated with GLP-1 for 6 hours. F, CCK secretion from INS-1 β-cells treated with GLP-1 for 6 hours. Error bars are mean ± SEM; n ≥ 3 for all experiments; *, P < .05; **, P < .01.

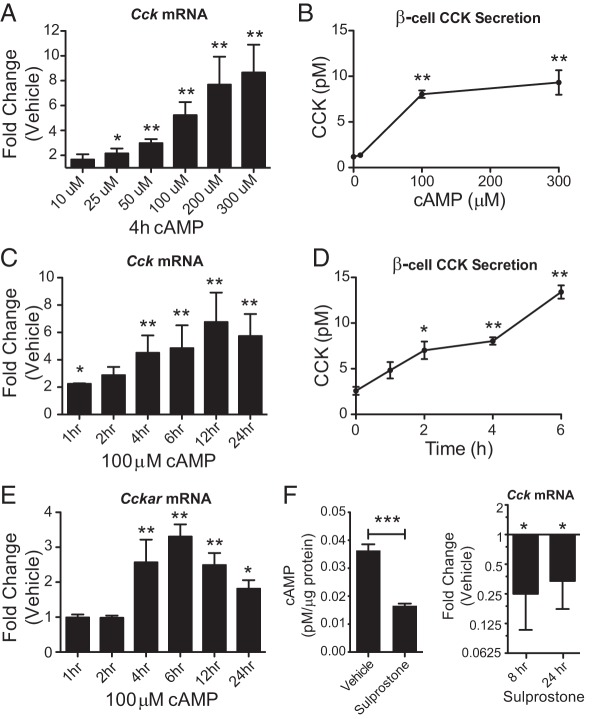

GLP-1 and cAMP stimulate β-cell production and secretion of CCK

Because GLP-1 and CCK are both made in the islet and function similarly to protect β-cells from apoptosis (8, 18–20), we wanted to explore the relationship between the hormones. Confirming previous reports of islet Cck up-regulation in obesity (7, 8), we find that Cck transcription is significantly increased in the islets from the same ob/ob mice that also secrete increased active GLP-1 (P = .0002) (Figure 1D). In fact, GLP-1 secretion is highly correlated with Cck expression (R2 = 0.86, P = .003). Given the coordinate up-regulation in obesity, we hypothesized that GLP-1 signaling may regulate CCK.

It has been shown that α-cells produce GLP-1 in the islet and CCK is predominantly produced in β-cells in obesity (8, 18, 19, 22). Therefore, to avoid confounding effects on other cell types, we analyzed GLP-1 regulation of CCK in the rat β-cell line, INS-1. Treatment with biologically active GLP-1 stimulated an approximately 2-fold increase in Cck gene expression at higher doses of GLP-1 (Figure 1E). There is a similar increase in secretion of sulfated CCK after GLP-1 treatment (P = .004) (Figure 1F).

Because GLP-1 signals at least in part through stimulation of β-cell cAMP production (13), INS-1 β-cells were treated with a membrane permeable cAMP analog (8-CPT-cAMP, referred to as cAMP) to determine whether cAMP can regulate CCK. Cck expression was increased with cAMP concentrations above 25μM. CCK secretion was also stimulated by cAMP concentrations above 100μM. Changes in both gene expression and secretion were cAMP dose dependent (Figure 2, A and B). We observed a 2-fold increase in Cck expression after just 1 hour of treatment with 100μM cAMP (Figure 2C), suggesting that Cck is an immediate early gene. The stimulation of Cck by cAMP continues to increase over the course of 24 hours and is accompanied by increased CCK secretion (Figure 2, C and D). Interestingly, Cckar expression is also up-regulated by cAMP in the β-cells (Figure 2E). However, the delayed response after 4 hours suggests that Cckar up-regulation is an indirect effect. Taken together, we show that cAMP can stimulate the CCK signaling pathway in β-cells.

Figure 2.

cAMP is necessary and sufficient for β-cell CCK stimulation. A and B, Measurement of CCK expression and secretion after 4 hours of 8-CPT-cAMP treatment at various doses in INS-1 β-cells. C and D, CCK expression and secretion at multiple time points after 100μM 8-CPT-cAMP treatment. E, Cckar gene expression at multiple time points after 100μM 8-CPT-cAMP treatment. F, cAMP and Cck gene expression measurements in INS-1 β-cells treated with sulprostone. Error bars are mean ± SEM; n ≥ 3 for all experiments; *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001.

The prostaglandin E3 (EP3) receptor is a Gαz-coupled GPCR that inhibits adenylate cyclase and thereby reduces cAMP levels when activated. In β-cells, EP3 activation reduces cAMP levels and blocks insulin secretion (23). To determine whether cAMP signaling is necessary for Cck expression, we treated β-cells with the EP3 receptor agonist sulprostone. Treatment of INS-1 β-cells with sulprostone caused a significant reduction in both cellular cAMP levels and basal Cck gene expression (P < .05) (Figure 2F). This demonstrates that β-cell Cck expression is dependent on cAMP and its GLP-1-mediated stimulation likely occurs as a direct result of cAMP targeting.

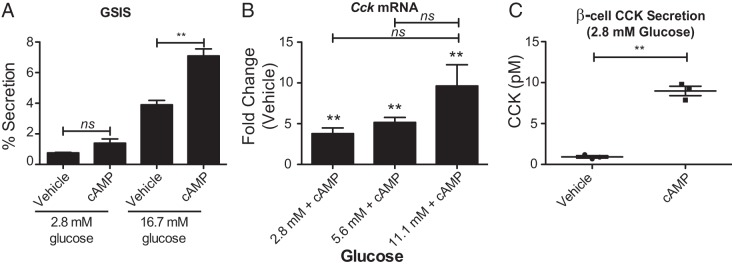

Insulin secretion and normoglycemia are not required for Cck stimulation

The ability of GLP-1 to act as an insulin secretagogue is dependent on the availability of glucose (24). Under normal glucose conditions cAMP also stimulates insulin secretion, raising the possibility that insulin itself could be signaling back on the β-cell to stimulate CCK production. To determine whether cAMP-mediated potentiation of insulin secretion is required to up-regulate CCK expression and secretion, we first analyzed how glucose affects the ability of cAMP treatment to stimulate INS-1 β-cell insulin release. Glucose stimulated insulin secretion was measured from β-cells alone or in the presence of 100μM cAMP. Although cAMP enhances insulin secretion by 2-fold at high (16.7mM) glucose (P = .004), it does not significantly stimulate insulin release at low (2.8mM) glucose (Figure 3A), supporting its known role as a potentiator of insulin secretion above a stimulatory glucose threshold of approximately 7mM glucose (25). Therefore, in low-glucose conditions, the effects of cAMP on CCK expression can be analyzed independent of enhanced insulin secretion or signaling. β-cells were preincubated in low (2.8mM), basal (5.6mM), or high (11.1mM) glucose for 1 hour before the addition of 300μM cAMP for an additional 4 hours. In low-glucose conditions there is still a robust stimulation of Cck expression, although the up-regulation is augmented by high glucose (Figure 3B). Increased gene expression correlates with increased CCK secretion, even in low-glucose conditions, where cAMP does not potentiate insulin secretion (Figure 3C). Despite the glucose-sensitive nature of insulin secretion potentiation by cAMP, stimulation of CCK secretion is nearly identical between low and high-glucose conditions. This further supports the conclusion that CCK secretion is not dependent on glucose or insulin secretion. Importantly, it suggests that CCK secretion may be stimulated through a mechanism distinct from that of insulin.

Figure 3.

cAMP-mediated stimulation of CCK is not dependent on insulin secretion. A, Glucose stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) of INS-1 β-cells treated with vehicle or 8-CPT-cAMP. B, Analysis of 8-CPT-cAMP stimulated Cck expression in the presence of various levels of glucose. **, significance is indicated relative to vehicle control, calculated by Student's t test. Comparisons between different glucose concentrations were calculated by ANOVA. C, Measurement of CCK secretion stimulation by 8-CPT-cAMP in the presence of low glucose. Error bars are mean ± SEM; n ≥ 3 for all experiments; **, P < .01, ns = not significant.

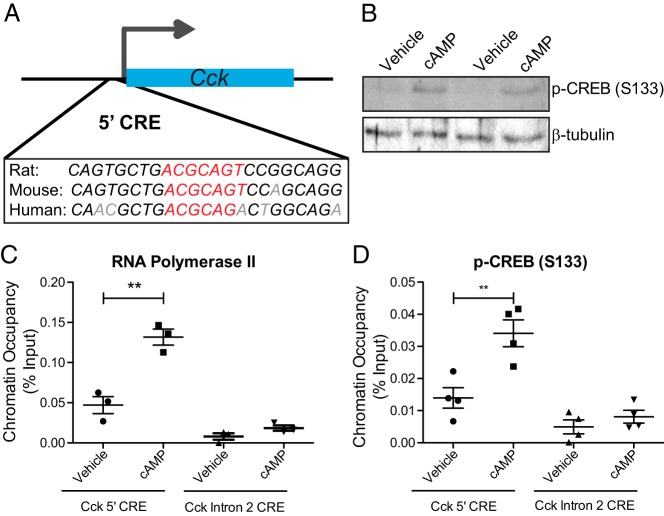

Cck is directly targeted by cAMP and GLP-1-stimulated CREB in the β-cell

Treatment of INS-1 β-cells with cAMP induces a 2-fold up-regulation of CCK within 1 hour of treatment, suggesting that Cck is an immediate early gene directly regulated by cAMP. The Cck promoter also contains a conserved CRE (5′-CRE) (Figure 4A). The canonical cAMP-regulated transcription factor is CREB. The occupancy of activated CREB, phosphorylated at Ser122 (p-CREB), was analyzed by ChIP at the 5′-CRE after cAMP treatment (300μM, 4 h). These treatment conditions stimulate a clear increase in total cellular p-CREB (Figure 4B). As might be expected for the nearly 10-fold up-regulation of Cck under these conditions (Figure 2A), there is a robust recruitment of RNA polymerase II to the 5′-CRE (Figure 4C) with no change in occupancy at a nearby putative CRE in intron 2 of Cck. There is also p-CREB recruitment to the promoter with cAMP treatment, with no change at the nearby intron 2 CRE (Figure 4D). This demonstrates that cAMP directly regulates Cck through recruitment of active phosphorylated CREB specifically to the 5′-CRE in the Cck promoter region.

Figure 4.

Cck is directly regulated by cAMP-stimulated p-CREB. A, Conservation of the CRE (red) in the CCK promoter region (5′-CRE). Nonconserved bases are shown in gray. B, Western blotting of CREB phosphorylated at Ser133 in vehicle and cAMP-treated INS-1 β-cells. C and D, ChIP analysis of RNA polymerase II (C) and p-CREB (D) occupancy at the 5′-CRE and at a CRE located in intron 2 of Cck that serves as a negative control. Error bars are mean ± SEM; n ≥ 3 for all experiments; **, P < .01, ns = not significant.

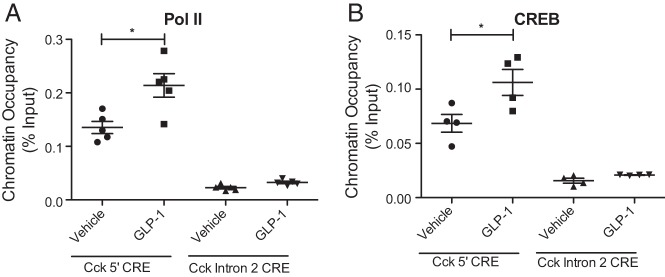

To determine whether GLP-1 regulates Cck through cAMP-mediated CREB targeting in the β-cell, INS-1 were treated with 50nM GLP-1 for 6 hours, conditions sufficient to stimulate approximately a 2-fold increase in CCK expression (Figure 1E). GLP-1 treatment of β-cells causes recruitment of both RNA polymerase II (Figure 5A) and CREB (Figure 5B) to the 5′-CRE without any change in occupancy at the nearby intron 2 CRE. This indicates that GLP-1 stimulates Cck transcription through cAMP-mediated recruitment of CREB to the 5′-CRE in the Cck promoter region.

Figure 5.

GLP-1 regulates Cck through CREB targeting. ChIP analysis of (A) RNA polymerase II and (B) CREB occupancy at the 5′-CRE and at a CRE located in intron 2 of Cck that serves as a negative control. Error bars are mean ± SEM; n ≥ 3 for all experiments; *, P < .05.

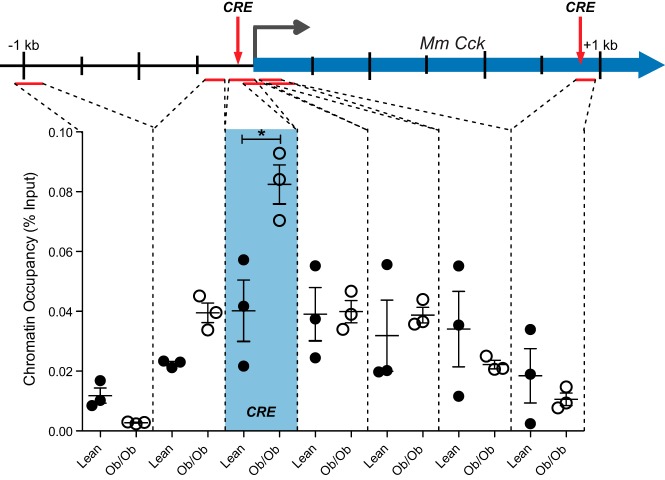

CREB is recruited to the islet Cck promoter specifically in obesity

Islet secretion of GLP-1 is increased in nondiabetic obesity (Figure 1C) and GLP-1 secretion is highly correlated with Cck expression (Figure 1D). Because we find that cultured β-cells treated with GLP-1 demonstrate recruitment of CREB to the Cck promoter (Figure 5B) and enhanced Cck transcription (Figure 1E), we hypothesized that CREB was responsible for this dramatic increase in Cck transcription in obese mouse islets. To test this hypothesis, we measured CREB recruitment to the Cck locus in intact mouse islet. Islets were isolated from C57BL/6J lean and ob/ob mice between 11 and 14 weeks of age. Islets were pooled from multiple mice to achieve 1000–1500 islets per biological replicate. ChIP was then performed to analyze CREB occupancy across the Cck gene. As shown in Figure 6, CREB is specifically recruited to a CRE located immediately upstream of the transcription start site in obese mice (P = .026). Neighboring locations show little to no change in CREB occupancy in ob/ob vs lean mice, including at a nearby intronic CRE, demonstrating the specificity of recruitment to the CRE near the transcriptional start site. Taken together, we show that GLP-1 regulates β-cell CCK and is likely responsible for islet Cck stimulation in nondiabetic obesity through targeted CREB recruitment to the locus.

Figure 6.

CREB is specifically recruited to the Cck promoter in obese mouse islets. ChIP was performed using a CREB antibody to measure chromatin occupancy at and near the CRE in the promoter region of the Cck gene in islets from lean (closed circles) and Leptinob/ob (open circles) mice. Regions analyzed by qPCR are indicated by red lines. The promoter CRE and an intronic CRE in the Cck gene are marked by the red arrows, and chromatin occupancy at this site is in the blue shaded box. Each point represents one independent biological replicate consisting of pooled islets from 2–4 mice. Error bars are mean ± SEM; n ≥ 3 for all experiments; *, P < .05.

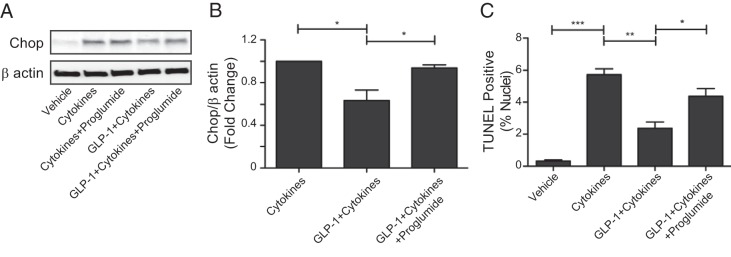

CCK receptor inhibition reduces GLP-1-mediated protection of β-cells from cytokine-induced apoptosis

Because GLP-1 regulates CCK and there is evidence that both GLP-1 and CCK can prevent β-cell apoptosis (13), we wanted to determine whether CCK is required for GLP-1-mediated apoptosis protection. We used proglumide, a nonselective CCK inhibitor that blocks its interaction with both A and B type receptors, at a concentration that has been shown to significantly impair the ability of CCK to stimulate amylase release from pancreatic acinar cells (26). INS-1 cells in culture were treated with proinflammatory cytokines in the presence of GLP-1 alone or GLP-1 plus proglumide to determine whether blocking CCK signaling inhibits GLP-1-mediated protection from cytokine-induced apoptosis. We first measured expression of the stress response protein CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) and found that although GLP-1 reduced the cytokine-mediated induction of CHOP, proglumide blocked this effect (P < .05) (Figure 7, A and B). Proglumide in the absence of GLP-1 had no effect on cytokine-induced CHOP expression (Figure 7A). Apoptosis was then measured by TUNEL assay (Figure 7C). Cytokine treatment increased the number of TUNEL-positive cells from 0.3% to 5.7% of the population (P < .001). The presence of GLP-1 reduced the proportion of TUNEL-positive cells to 2.4% (cytokines vs GLP-1+cytokines; P < .01), whereas GLP-1 was less effective at reducing apoptosis when CCK signaling was inhibited with proglumide (4.4% TUNEL-positive cells, GLP-1+cytokines vs GLP-1+cytokines+proglumide; P < .05). We conclude that stimulation of CCK is a novel mechanism by which GLP-1 protects β-cells from apoptosis, and regulation of CHOP is part of this mechanism.

Figure 7.

GLP-1 uses CCK to protect β-cells from apoptosis. A, Representative Western blotting showing Chop protein expression in INS-1 β-cells treated with cytokines, GLP-1, and/or the CCK receptor antagonist, proglumide. B, Quantification of Chop protein expression where normalized changes in protein expression are represented as fold-change relative to cytokine treatment. One-way ANOVA, P = .0096. C, TUNEL analysis of INS-1 β-cells treated with cytokines, GLP-1, and/or proglumide. One-way ANOVA, P < .0001. Error bars are mean ± SEM; n = 3 for all experiments; Stars indicate significance calculated by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test, where *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001.

Discussion

There has been a recent push to understand how cells within the pancreatic islet communicate with each other to stimulate β-cell proliferation or protection from apoptosis. Of particular interest is the stimulation of GLP-1 production in pancreatic α-cells and its role in β-cell function (18–21). We provide evidence that active GLP-1 is secreted from pancreatic islets as a function of BMI/obesity (Figure 1, A and C). Our finding of increased active GLP-1 secretion from ob/ob mouse islets is consistent with the previous observation that ob/ob islets express increased levels of prohormone convertase 1/3 (18), the enzyme that processes proglucagon into GLP-1. We hypothesize that this islet-produced GLP-1 acts in a paracrine fashion to regulate a signaling network that is activated specifically in obesity. GLP-1 is rapidly degraded by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (27, 28), and it has been suggested that the effects of GLP-1 on the β-cell are not due to gut-derived hormone but perhaps neuronal or even paracrine action (29). Neither diabetes nor obesity is associated with a significant change in serum GLP-1 levels in humans (30, 31); however, we now show that islet GLP-1 secretion is increased in obesity (Figure 1A). This suggests that intraislet paracrine function of GLP-1 may be important for islet function and survival in obesity.

We observe a strong correlation between islet GLP-1 secretion and Cck expression (Figure 1D). Furthermore, we find that GLP-1 can directly stimulate β-cell CCK transcription and secretion (Figure 1, E and F). This CCK stimulation appears to be mediated through cAMP signaling (Figure 2) and occurs via direct targeting of the Cck promoter by CREB (Figures 4 and 5). Importantly, we also observe CREB occupancy at the Cck promoter in vivo, in the islets of obese mice (Figure 6) where Cck is actively transcribed (Figure 1D and Ref. 8). Based on these data, we propose a model where GLP-1 secreted from obese islets acts in a paracrine manner to stimulate β-cell CCK production. The islet-derived CCK may act locally to protect the β-cell from apoptosis (8). This protection likely occurs in a cell autonomous manner through paracrine regulation, as we find that CCK secreted from the β-cell contributes to GLP-1-mediated protection from cytokine-induced apoptosis (Figure 7) and β-cell Cckar is up-regulated when there is increased CCK secretion (Figure 2E). Interestingly, CCK treatment also seems to enhance α-cell GLP-1 production under high-fat diet (HFD) conditions (32), suggesting a positive feedback loop that amplifies this pathway within the islet. These hormones may function together locally in vivo as insulin secretagogues, in the protection of β-cells from apoptosis, and/or the stimulation of proliferation.

Of particular interest is our observation that CCK production and secretion is enhanced by cAMP even under low-glucose conditions and in the absence of stimulated insulin secretion (Figure 3). This suggests a mechanism of CCK secretion that is distinct from that of insulin and raises the question of whether CCK secretion is directly regulated by cAMP. One possibility is that the increased secretion is a passive response, simply representative of increased CCK production in the islet, rather than regulated secretion. However, because CCK secretion from intestinal cells is regulated (33, 34), we expect that this will also be the case in the islet. Furthermore, although we cannot rule out the possibility that some CCK is present with insulin in dense core granules, we can reasonably hypothesize that this is not the predominant mechanism of secretion as CCK secretion occurs in the absence of insulin secretion (Figure 3). If the release of CCK is regulated in islets, we suspect it is packaged in synaptic-like microvesicles. It will be interesting to explore the mechanisms of islet CCK secretion and differentiate between cAMP- or depolarization-regulated and alternate mechanisms of secretion.

If the GLP-1/CCK islet incretin pathway is critical for β-cell survival in obesity, then it would be expected that perturbation of any of the components would lead to type 2 diabetes. Type 2 diabetic islets actually secrete more GLP-1 than nondiabetic islets (21). Similarly, mice treated with low-dose streptozotocin have increased pancreatic α-cell secretion of GLP-1 along with the expected reduction of β-cell mass and diabetic phenotype (35). Together, this suggests that an intraislet defect downstream of GLP-1 secretion in this pathway may play a role in the disease. Indeed, type 2 diabetic islets have decreased GLP1R expression (36), and whole-body GLP1R null mice exhibit abnormalities in islet adenylate cyclase and increased sensitivity to β-cell injury (37, 38). In GLP1R null mice, low-dose streptozotocin treatment leads to even higher levels of islet apoptosis (35). In light of our observation that CCK signaling contributes to GLP-1-mediated protection from apoptosis (Figure 7), we propose that the increased susceptibility to β-cell apoptosis with loss of GLP1R signaling may be partially due to the inability to up-regulate CCK production. Careful consideration of models will be critical in studying this pathway, however, because HFD induced obesity does not always stimulate islet CCK. For example, we have found that Black and Tan BRachyury mice fed a HFD for 33 weeks starting at weaning display a 16-fold up-regulation of CCK (8). Alternatively, in a recent study where CREB was knocked out in the β-cells of C57BL/6J mice and mice were placed on a HFD for a shorter amount of time (39), control mice did not have increased islet Cck expression after HFD feeding (Kaestner, K., unpublished data). Therefore, this particular model cannot be used to determine whether CREB is necessary for the up-regulation of CCK in obesity. In the future, either genetic induction of obesity in these mice or in the newly developed mouse model where GLP1R is absent from the β-cell (40) may be used to address this question.

In conclusion, we provide a novel description of how islet production of incretins is regulated. Furthermore, we describe a mechanism whereby GLP-1-directed therapies might exert protective effects on the β-cell. We provide evidence that activation of this pathway is a natural physiological response, or adaptation, to obesity. It is clear that harnessing the plasticity and adaptation potential of the islet has exciting implications for the future of diabetes therapy (41). In this context, combining CCK therapy with GLP-1 therapy may prove useful to halt or slow the progression of diabetes by preventing β-cell death. Acute treatment of HFD-fed mice with a combination of CCK and GLP-1 has already been shown to lower blood glucose and improve glucose tolerance (42). Based on our observations, we propose that the long-term effects of this treatment may be even more beneficial for maintaining normoglycemia through maintenance of β-cell mass.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed using facilities and resources from the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital. This work does not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. We thank Allison Brill for technical assistance in performing the initial sulprostone treatments.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIH-NIDDK) Grant 1K01DK102492 (to A.K.L.); the National Institute on Aging Grant 5T32AG000213 (to J.C.N.); the NIH-NIDDK Grant 1RO1DK102598 (to M.E.K.); and the NIH-NIDDK Grant DK083442, the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Grant 1101BX001880, the University of Wisconsin, and the Wisconsin Partnership Program (D.B.D.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- 8-CPT-cAMP

- 8-(4-chlorophenyl) thio-cyclic AMP

- BMI

- body mass index

- CCK

- cholecystokinin

- CCKAR

- CCK A receptor

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CHOP

- CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein

- CRE

- cAMP response element

- CREB

- CRE binding protein

- EP3

- prostaglandin E3 receptor

- GLP-1

- glucagon-like peptide 1

- GLP1R

- GLP-1 receptor

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- HFD

- high-fat diet

- INS-1

- rat insulinoma cells

- p-CREB

- phospho-CREB

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- TUNEL

- TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling.

References

- 1. Linnemann AK, Baan M, Davis DB. Pancreatic β-cell proliferation in obesity. Adv Nutr. 2014;5(3):278–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Back SH, Kang S-W, Han J, Chung H-T. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the β-cell pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012(5):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liddle RA. Cholecystokinin cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:221–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahrén B, Lundquist I. Effects of two cholecystokinin variants, CCK-39 and CCK-8, on basal and stimulated insulin secretion. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1981;18(4):345–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dufresne M, Seva C, Fourmy D. Cholecystokinin and gastrin receptors. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(3):805–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Woods SC, D'Alessio DA. Central control of body weight and appetite. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11 suppl 1):s37–s50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lan H, Rabaglia ME, Stoehr JP, et al. Gene expression profiles of nondiabetic and diabetic obese mice suggest a role of hepatic lipogenic capacity in diabetes susceptibility. Diabetes. 2003;52(3):688–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lavine JA, Raess PW, Stapleton DS, et al. Cholecystokinin is up-regulated in obese mouse islets and expands β-cell mass by increasing β-cell survival. Endocrinology. 2010;151(8):3577–3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deavall DG, Raychowdhury R, Dockray GJ, Dimaline R. Control of CCK gene transcription by PACAP in STC-1 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279(3):G605–G612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hansen TV, Rehfeld JF, Nielsen FC. Mitogen-activated protein kinase and protein kinase A signaling pathways stimulate cholecystokinin transcription via activation of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate response element-binding protein. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13(3):466–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nielsen FC, Pedersen K, Hansen TV, Rourke IJ, Rehfeld JF. Transcriptional regulation of the human cholecystokinin gene: composite action of upstream stimulatory factor, Sp1, and members of the CREB/ATF-AP-1 family of transcription factors. DNA Cell Biol. 1996;15(1):53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Drucker DJ. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab. 2006;3(3):153–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lavine JA, Attie AD. Gastrointestinal hormones and the regulation of β-cell mass. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1212(1):41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rabaglia ME, Gray-Keller MP, Frey BL, Shortreed MR, Smith LM, Attie AD. α-Ketoisocaproate-induced hypersecretion of insulin by islets from diabetes-susceptible mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289(2):E218–E224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Neuman JC, Truchan NA, Joseph JW, Kimple ME. A method for mouse pancreatic islet isolation and intracellular cAMP determination. J Vis Exp. 2014;(88):e50374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bhatnagar S, Oler AT, Rabaglia ME, et al. Positional cloning of a type 2 diabetes quantitative trait locus; tomosyn-2, a negative regulator of insulin secretion. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(10):e1002323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Im H, Grass JA, Johnson KD, Boyer ME, Wu J, Bresnick EH. Measurement of protein-DNA interactions in vivo by chromatin immunoprecipitation. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;284:129–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kilimnik G, Kim A, Steiner DF, Friedman TC, Hara M. Intraislet production of GLP-1 by activation of prohormone convertase 1/3 in pancreatic α-cells in mouse models of β-cell regeneration. Islets. 2010;2(3):149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hansen AM, Bödvarsdottir TB, Nordestgaard DN, et al. Upregulation of α cell glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) in Psammomys obesus—an adaptive response to hyperglycaemia? Diabetologia. 2011;54(6):1379–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ellingsgaard H, Hauselmann I, Schuler B, et al. Interleukin-6 enhances insulin secretion by increasing glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from L cells and α cells. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1481–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marchetti P, Lupi R, Bugliani M, et al. A local glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) system in human pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2012;55(12):3262–3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ellingsgaard H, Ehses JA, Hammar EB, et al. Interleukin-6 regulates pancreatic α-cell mass expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(35):13163–13168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kimple ME, Keller MP, Rabaglia MR, et al. Prostaglandin E2 receptor, EP3, is induced in diabetic islets and negatively regulates glucose- and hormone-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2013;62(6):1904–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meloni AR, DeYoung MB, Lowe C, Parkes DG. GLP-1 receptor activated insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells: mechanism and glucose dependence. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(1):15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kimple ME, Joseph JW, Bailey CL, et al. Gαz negatively regulates insulin secretion and glucose clearance. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(8):4560–4567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hahne WF, Jensen RT, Lemp GF, Gardner JD. Proglumide and benzotript: members of a different class of cholecystokinin receptor antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78(10):6304–6308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deacon CF, Johnsen AH, Holst JJ. Degradation of glucagon-like peptide-1 by human plasma in vitro yields an N-terminally truncated peptide that is a major endogenous metabolite in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(3):952–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hansen L, Deacon CF, Orskov C, Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide-1-(7–36)amide is transformed to glucagon-like peptide-1-(9–36)amide by dipeptidyl peptidase IV in the capillaries supplying the L cells of the porcine intestine. Endocrinology. 1999;140(11):5356–5363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Donath MY, Burcelin R. GLP-1 Effects on islets: hormonal, neuronal, or paracrine? Diabetes Care. 2013;36(suppl 2):S145–S148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Calanna S, Christensen M, Holst JJ, et al. Secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses of clinical studies. Diabetologia. 2013;56(5):965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wadden D, Cahill F, Amini P, et al. Circulating glucagon-like peptide-1 increases in response to short-term overfeeding in men. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2013;10(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Irwin N, Montgomery IA, Moffett RC, Flatt PR. Chemical cholecystokinin receptor activation protects against obesity-diabetes in high fat fed mice and has sustainable beneficial effects in genetic ob/ob mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85(1):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Y, Chandra R, Samsa LA, et al. Amino acids stimulate cholecystokinin release through the Ca2+-sensing receptor. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300(4):G528–G537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chandra R, Wang Y, Shahid RA, Vigna SR, Freedman NJ, Liddle RA. Immunoglobulin-like domain containing receptor 1 mediates fat-stimulated cholecystokinin secretion. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(8):3343–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vasu S, Moffett RC, Thorens B, Flatt PR. Role of endogenous GLP-1 and GIP in β cell compensatory responses to insulin resistance and cellular stress. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e101005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shu L, Matveyenko AV, Kerr-Conte J, Cho JH, McIntosh CH, Maedler K. Decreased TCF7L2 protein levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus correlate with downregulation of GIP- and GLP-1 receptors and impaired β-cell function. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(13):2388–2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Flamez D, Gilon P, Moens K, et al. Altered cAMP and Ca2+ signaling in mouse pancreatic islets with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor null phenotype. Diabetes. 1999;48(10):1979–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li Y. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling modulates β cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(1):471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shin S, Le Lay J, Everett LJ, Gupta R, Rafiq K, Kaestner KH. CREB mediates the insulinotropic and anti-apoptotic effects of GLP-1 signaling in adult mouse β-cells. Mol Metab. 2014;3(8):803–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith EP, An Z, Wagner C, et al. The role of β cell glucagon-like peptide-1 signaling in glucose regulation and response to diabetes drugs. Cell Metab. 2014;19(6):1050–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dor Y, Glaser B. β-Cell dedifferentiation and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):572–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Irwin N, Hunter K, Montgomery IA, Flatt PR. Comparison of independent and combined metabolic effects of chronic treatment with (pGlu-Gln)-CCK-8 and long-acting GLP-1 and GIP mimetics in high fat-fed mice. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(7):650–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]