Abstract

Although previous studies have identified a protective effect of marriage on risky health behaviors, gaps remain in our understanding of how marriage improves health, particularly among African Americans. This study uses longitudinal data to take selection into account and examines whether marital trajectories that incorporate timing, stability, and duration of marriage affect health risk behaviors among a community cohort of urban African Americans followed for 35 years (N = 1,049). For both men and women, we find six marital trajectories. Men and women in consistently married trajectories are less likely to smoke, drink heavily (women only), and use illegal drugs than those in unmarried or previously married trajectories. Late marrying men do not fare worse in midlife than men in earlier marrying trajectories, but late marrying women show increased risk of midlife drug use. Results suggest policies supporting marriage may have an impact on health but only if stable unions are achieved.

Keywords: African Americans, health, longitudinal studies, marriage, substance use

Marriage, particularly high-quality marriage, has been shown repeatedly to be associated with better health (Horwitz, White, & Howell-White, 1996; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988). However, most studies that have examined marriage and health have focused on the general population and not examined the relationship among ethnic minorities (Koball, Moiduddin, Henderson, Goesling, & Besculides, 2010). Thus, our understanding of how marriage and health are related for African Americans is limited. It is critical to gain insight into how marriage affects African American health since some government programs (e.g., welfare) have unintentionally discouraged marriage among poor African Americans, whereas other government programs, such as the African American Healthy Marriage and the Responsible Fatherhood Initiatives, have targeted this group for marital promotion programs (Cherlin, 2003; Lane et al., 2004). A recent special issue of the Journal of Family Issues has identified a number of gaps in the literature, including understanding of subgroup differences within African American populations (Koball et al., 2010); this study attempts to address some of these gaps.

In this article, we focus on a community cohort of urban African Americans with low rates of marriage and significant health risk behaviors. Studies show that African Americans are less likely to marry overall, more likely to marry later in life, and more likely to experience marital dissolution compared with Whites (Cherlin, 1998; Pinderhughes, 2002). These issues are even more pronounced for poor, urban populations where nontraditional family patterns are common (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002). These differences in marriage and divorce rates between African American and White populations are often attributed to different attitudes and cultural practices around marriage (South, 1993), as well as differences in structural conditions that serve as barriers to marriage (Wilson, 1987), such as high incarceration rates and low employment rates in urban centers (Lopoo & Western, 2005; Wilson & Neckerman, 1986).

Since marriage has been found to be protective against poor health, it may explain some of the health disparities between African Americans and Whites. African American adults have nearly twice the mortality rate of White adults in midlife (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2004). African Americans experience higher rates of chronic conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease (Fryar, Hirsch, Eberhardt, Yoon, & Wright, 2010; NCHS, 2010), and they consistently rate their overall health as poorer than Whites (NCHS, 2010; Pleis, Lucas, & Ward, 2009); however, the role of marriage in these health disparities is unknown. Thus, research is necessary to determine how low rates of marriage and the high marital instability experienced by African Americans contribute to health status.

A major way that marriage can affect overall health later in life is through health behaviors in adulthood. Theories of social integration attribute the health benefits of marriage to the role that spouses play in providing social control, particularly over risky health behaviors, such as problematic drinking, smoking, and drug use (Berkman & Glass, 2000; Durkheim, 1951). Spouses actively monitor and discourage participation in these behaviors, and marriage creates an environment where unhealthy behaviors are less normative and deviant friend networks diminish. For example, Anderson (2000) suggested that low-income married African American men in the inner cities are less likely to spend their nights and weekends hanging out in the streets with unmarried friends, lowering the likelihood of engaging in risky health behaviors. Similarly, Bachman Wadsworth, O’Malley, Johnston, and Schulenberg (1997) and Bachman et al. (2002) offered that marriage affects social and recreational activities, with married individuals attending parties, bars, clubs, and other such establishments less frequently. Duncan, Wilkerson, and England (2006) write that “marriage entails cleaning up one’s act” and “eschewing behavior associated with the single life” (p. 692).

Empirically, research suggests that marriage can reduce certain risky health behaviors, although findings are not entirely consistent, and the strongest evidence comes from longitudinal, national samples. For example, longitudinal research based on the Monitoring the Future Study (Bachman et al., 1997; Bachman et al., 2002) has shown that entry into first marriage for men and women is related to a decrease in the frequency of smoking and heavy drinking and marijuana use, whereas these behaviors all increase at the time of divorce and decrease with remarriage. Merline, O’Malley, Schulenberg, Bachman, and Johnston (2004) found marriage effects extend into the mid- 30s. They found that after controlling for earlier risk, being in a state of marriage was related to a lower likelihood of smoking, heavy drinking, and drug use (i.e., marijuana, cocaine, prescription drug misuse). Research using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (Duncan et al., 2006), which tested racial differences in effects, found that marriage led to a decrease in binge drinking and marijuana use, particularly for men, with similar reductions for African Americans and Whites. They did not find an association with smoking. In an examination of reductions in heavy drinking among Black and White couples during the first 2 years of marriage, Mudar, Kearns, and Leonard (2002) only found reductions for White couples.

Although overall findings suggest that marriage may reduce substance use, previous work has demonstrated some negative consequences of marriage, including increased stress and weight gain for African American and White populations (Harris, Lee, & DeLeone, 2010; Shafer, 2010).

Negative consequences may also be tied to marital satisfaction, as studies have found martial conflict to be related to risky health behaviors and poor mental health (Horwitz & White 1991; Robbins & Martin, 1993). In examining potential health consequences of marriage, it is important to take gender into account. In addition to patterns of marriage differing for men and women, the health benefits of marriage may differ by gender too. A number of studies have found that marriage seems to provide greater health benefits for men than for women. For example, Duncan et al. (2006) did not find any effect of marriage on marijuana use for women and found a greater reduction in binge drinking for men than women. Umberson (1992) suggested that men, in particular, benefit from the social control provided by women since wives have been socialized to encourage their husbands to avoid unhealthy behaviors. Furthermore, women’s lower likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors before marriage may in part explain the greater benefits for men.

Evidence suggests that it is not simply the presence of a marital union that drives associations with health, but marriage timing, transitions, and duration can contribute to health outcomes (Dupre, Beck, & Meadows, 2009; Dupre & Meadows, 2007). However these dimensions have not been studied in depth, particularly among African Americans. For example, using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, Harris et al. (2010) found that early marriage (before age 26) did not protect against binge drinking, marijuana use, or cigarette smoking for African Americans as expected. (They did find some health benefits for Whites.) Since much of the research has focused on entry into and exiting out of marriage, the timing and the length of marriage are important dimensional qualities about which we have much to learn, particularly among African Americans.

It is necessary to consider selection effects when examining health benefits of marriage as there is evidence that healthy people are more likely to marry and less likely to separate or divorce (Goldman, 1993; Stutzer & Frey, 2006; Umberson, 1992). Factors such as socioeconomic status, family disadvantage, and poor health can decrease the likelihood of marriage and affect health (Axinn & Thorton, 1992; Larson & Holman, 1994; South, 2001). Thus, the relationship between marriage and health benefits is attributable both to the protective effects of marriage and to selection into marriage (Lillard & Panis, 1996; Waite, 1995). Further evidence suggests that risky health behaviors, such as drug use or heavy drinking, can lead to marital dissolution (Leonard & Rothbard, 1999), making it critical to take into account the propensity to engage in these behaviors before the marriage occurs. Finally, evidence suggests that cohabitation may provide some health benefits (e.g., Kurdek, 1991); thus, with high rates of cohabitation in some African American communities, it is important to take into account cohabitation when examining the health benefits of marriage (Waite, 1995). This study addresses several gaps in the literature by examining the relationship between marital trajectories and health behaviors in a cohort of urban African American men and women followed from age 6 to 42. With 35 years of data, we are able to characterize long-term patterns and transitions into and out of marriage. We model marriage in a dynamic fashion using latent growth curve analyses (Nagin, 2005), which allows for the examination of the presence, stability, and timing of marriage simultaneously. This represents an innovative way to capture the complexities of marriage over the life course, as marriage has been shown to follow distinct developmental trajectories (Dupre & Meadows, 2007; Karney & Bradbury, 1995). With longitudinal data gathered prospectively over the life course and covariate adjustment, we are able to partially account for selection into marriage, something lacking in much of the research on marriage and health. This study focuses on four research questions, as described below:

Does being in a consistently married trajectory compared with an unmarried trajectory relate to the risky health behaviors, namely, binge drinking, smoking, and drug use, controlling for characteristics that affect the likelihood of marriage in the first place?

Does the stability of marriage affect risky health behaviors? Compared with individuals in trajectories of marital dissolution, are those in married trajectories less likely to engage in risky health behaviors, or does marrying set an individual on a course to reduced risk?

Does the timing of marriage affect risky health behaviors? Are those in late marrying trajectories equally protected against health risk behaviors compared with those in earlier marrying trajectories?

Do the relationships between marital patterning and health behaviors differ by gender?

Method

Study Sample

Data come from the Woodlawn Study, an epidemiological, prospective study of a cohort of urban African American first graders from Woodlawn, a neighborhood community on the South Side of Chicago, followed from age 6 to age 42 (N = 1,242). The study began in the 1960s to focus on children’s mental health, broadly conceived. All families with children in first grade in one of the 12 elementary schools (public and private) in Woodlawn were asked to participate in the study; only 13 families declined. During first grade (age 6, 1966–1967), mothers and teachers were interviewed about the child’s family life, behavior, and health. Mothers (N = 939) and adolescents (age 16, N = 705) were assessed in 1976–1977. Mothers reported on their child and their family, and adolescents provided information on their psychological well-being, delinquency and drug use, family and peer relationships, and school activities. At age 32 (1992–1993, N = 952) and age 42 (2002–2003, N = 833), study participants provided information on their marriage, employment, substance use, mental health, physical health, social relationships, and families. In adulthood, we have found high rates of substance use and other health risk behaviors among this population. More details on the Woodlawn Study are available elsewhere (Crum et al., 2006; Ensminger, Juon, & Fothergill, 2002; Kellam, Branch, Agrawal, & Ensminger, 1975).

Attrition

This study was based on the 1,049 respondents who completed at least one adult interview and provided complete marital information (546 women and 503 men), representing 84% of the original cohort. Like all prospective studies, the Woodlawn Study has experienced attrition. A comparison of those with at least one adult interview with those missing both adult interviews revealed no statistically significant differences on key variables such as gender, classroom behavior, mother’s education, or adolescent substance use. Differences were found on poverty status, with those below the poverty line in first grade or adolescence less likely to be interviewed in adulthood and those with a criminal justice record more likely to be interviewed in young adulthood (81% vs. 74%).

Measures

Dependent variables

As measures of risky health behaviors, we included current smoking status, binge drinking, and illegal drug use; the leading cause of death in 2000 was tobacco (18.1% of total U.S. deaths); the third leading cause of death was alcohol consumption responsible for 3.5% of deaths, and illegal use of drugs responsible for about 1% of all deaths (Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004). We obtained self-reports of these behaviors from the interviews at age 32 in young adulthood and at age 42 in mid-adulthood. The self-report of smoking was a binary variable that indicated current smoking or not smoking at the time of the interview (49.9% in young adulthood, 42.3% in midlife). Binge drinking in young and mid-adulthood was measured by questions assessing whether the individual drank five or more drinks on drinking days when he/she drank the most in the past year. It was coded as yes or no (25.8% in young adulthood, 16.8% in midlife). Past year illegal drug use for both young adulthood and midlife was a self-report binary measure based on questions about the use of marijuana, cocaine, crack, LSD, hallucinogens, or heroin, as well as nonmedical use of barbiturates, tranquilizers, stimulants, amphetamines, or analgesics, within the past year (22.9% in young adulthood, 14.7% in midlife).

Independent variable

Marital trajectories were estimated using annualized data from the young adult and midlife interviews of the individual’s marital status at each age (ages 14–42). During the adult interviews, participants reported their current marital status, the number of times they had been married and the beginning and ending ages of these marriages, and changes in marital status since the last interview. Individuals were coded as unmarried if they had never been married, or were living with a partner, divorced, separated, or widowed.

Overall, 47% of men and 52% of women were married once, 10% of men and 8% of women were married two or more times, and the rest (43% of men and 40% of women) had never been married. Furthermore, among the married, the mean age of first marriage was 26.5 for men and 25.8 for women. The mean number of years married overall was 5.8 for both men and women. No differences by gender were statistically significant.

Covariates

To take into account selection into marriage and confounding with health behaviors, we incorporated numerous control variables. In terms of socioeconomic status, childhood poverty was based on reports at baseline by mothers of the family’s income and household size (52% fell below the federal poverty line). Mother’s education was measured as years of schooling the mother had completed by the baseline assessment (range = 0–18 years). We included a binary measure of whether the biological father was living in the household at the initial interview in first grade (46% had a father present). Mothers’ mental health was based on self-reports of how often at baseline they felt sad and blue (17% fairly/very often and 83% occasionally/hardly ever; Brown, Adams, & Kellam, 1981). Chronic illness was based on mother’s reports at baseline if she, the father, the child, or any siblings had a chronic health condition. Only 3.5% of the children had a chronic health problem, so this was combined with family members’ health to create a binary indicator of family chronic health problems (24%). To control for adolescent mental (7 items, α = .70) and depressed mood (7 items, α = .66) on a 6-point scale (Petersen & Kellam, 1977). The 14 items were summed because of the high correlation between the anxiety and depression totals (r= .55) and dichotomized into high (54%) versus low (46%) because of skewness. Adolescent substance use was a binary variable representing regular use (20 times or more) of alcohol or marijuana (61%). We also took into account whether the individual dropped out of school (26%). Finally, we controlled for cohabitation at the time of the interview (8% at young adulthood, 8% at midlife).

Analytical Approach

First, we estimated marriage trajectories from ages 14 to 42 for males and females separately, using a semiparametric mixed logit model (SAS Proc Traj), identifying the marital subgroups within the study population. Specifically, this longitudinal latent class model estimated the predicted probability of being married at each age within each trajectory group (Nagin, 2005). Based on posterior probability of membership, individuals were assigned to their most likely trajectory group. We identified the optimal number of trajectories based on the Bayesian information criteria (BIC) and other model diagnostics (Nagin, 2005).

Although the Bayesian information criteria statistic continued to decrease past six groups for both males and females, we selected the six-group model because of parsimony, the similarity of the group population and sample proportion, evaluation of the average posterior probabilities (which were high [0.94–0.99]), and evaluation of the odds of correct classification (which were more than the recommended number 5 [19.1–657.5]).

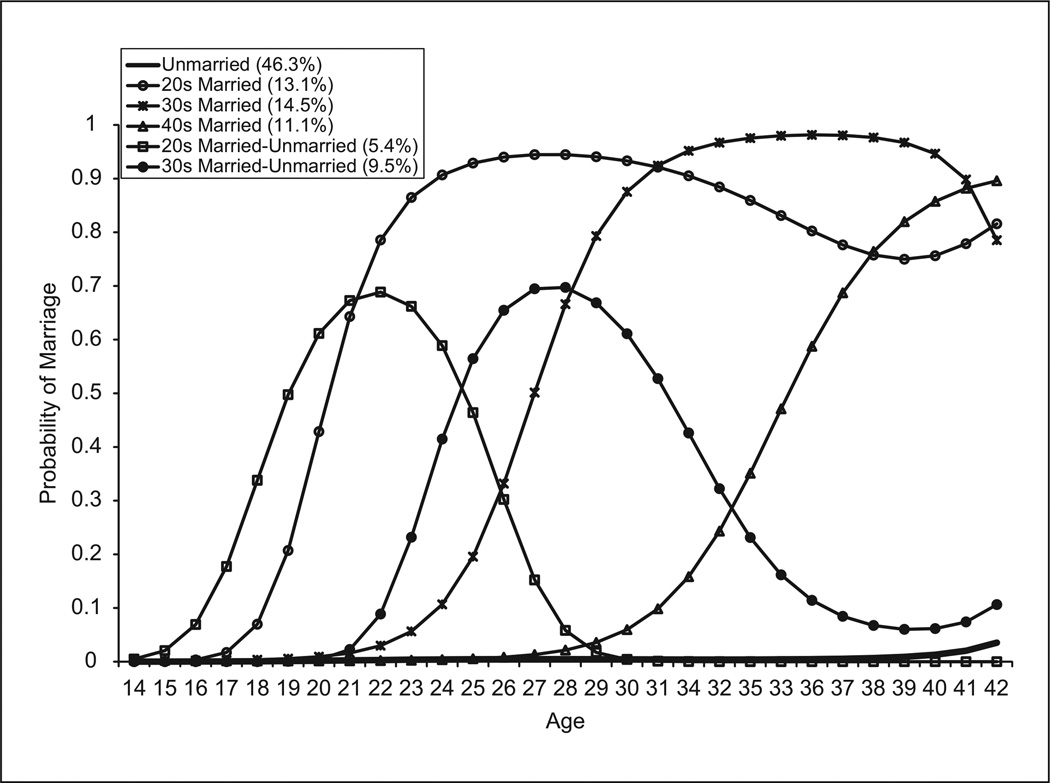

The group-based trajectory modeling revealed a six-group model for both men and women (Figures 1 and 2; see Doherty, Green, & Ensminger, in press). Almost half of the men (46.3%) were classified as unmarried; three groups represented stable marriage, but varied in the timing of their marriage—13.1% were classified as 20s married (those who predominantly married in their 20s), 14.5% as 30s married (those who predominantly married in their 30s), 11.1% as 40s married (those who predominantly married in their 40s). Two groups showed marital dissolution but at different times in the life course—5.4% were classified as 20s married-unmarried (those who married in their 20s but divorced/separated by 30s) and 9.5% as 30s married- unmarried (those who married in their 30s but divorced/separated by 40s). By age 42, 61.2% of the men were in one of three unmarried trajectories.

Figure 1.

Marriage trajectories: Males, ages 14 to 42 (N = 503)

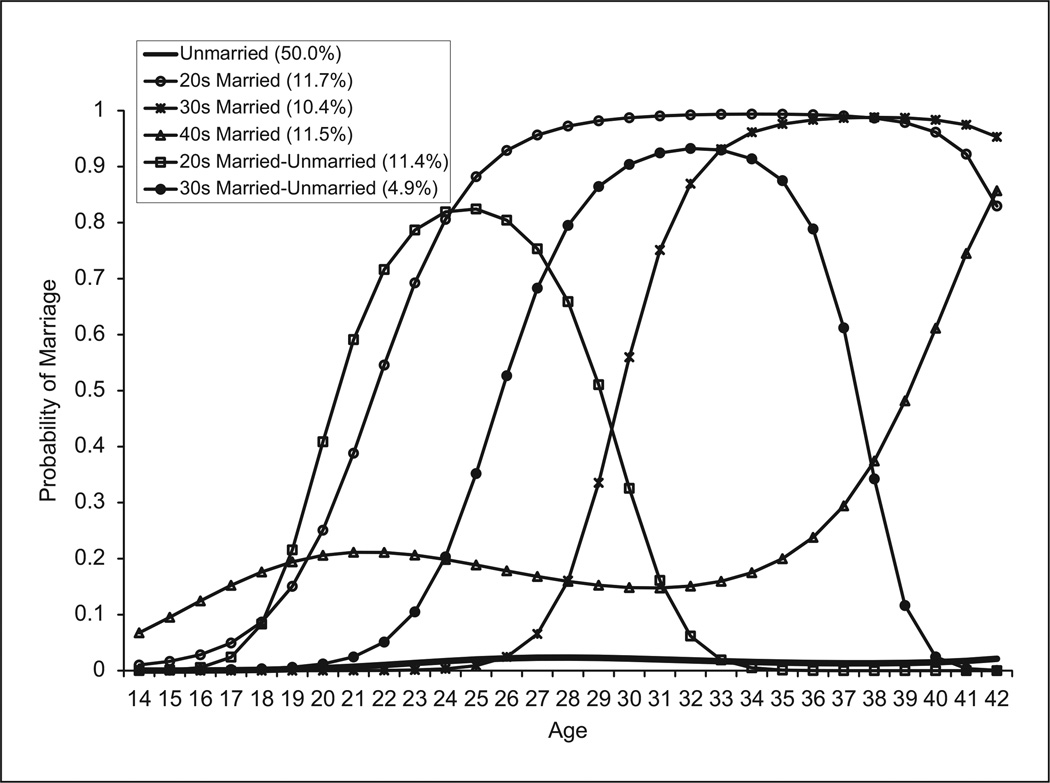

Figure 2.

Marriage trajectories: Females, ages 14 to 42 (N = 546)

The female trajectories were similar to male trajectories. Half of the women were classified as unmarried, 11.7% as 20s married, 10.4% as 30s married, 11.5% as 40s married, 11.4% as 20s married-unmarried, and 4.9% as 30s married-unmarried. Again, three trajectories stayed married into midlife, two experienced marital dissolution at different times in the life course, and one remained unmarried at age 42. Like men, by midlife, most women (66.3%) were in one of three unmarried trajectories.

Once the marital trajectories were established, we created 40 imputed data sets as recommend by Graham, Olchowski, and Gilreath (2007) in Stata10 by the MICE system of chained equations (Royston, 2009). Because data were considered to be missing at random, we conducted multiple imputation for missingness on control variables and outcomes to reduce bias from incomplete data, to preserve important characteristics of the data set as a whole and not to exclude an individual because he or she is missing one piece of data (Graham, 2009; Rubin, 1987). Multiple imputation was used for health variables in young adulthood (9.2%) and midlife (20.6%).

After examining bivariate associations, we conducted logistic regression on the 40 multiply imputed data sets (Carlin, Galati, & Royston, 2008); specifically, health risk behaviors were regressed on marital groupings separately for males and females, controlling for childhood and adolescent risk factors. Young adult models also control for cohabitation at age 32 whereas midlife models also control for cohabitation at age 42. We reported odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals, and two-tailed p values. To facilitate examination of certain research questions, marital trajectories were collapsed into broader categories, as detailed in the Results section. This allowed us to increase power and group together trajectories that demonstrated similar marital patterns up to that point in time. Categories were not collapsed if there was no conceptual or empirical reason to do so. In all instances of combining marital trajectories, preliminary analyses on the multivariate relationship of the individual trajectory with the health outcome were conducted to ensure similar relationships with health outcomes.

Results

those in the 30s married trajectory. Those who married later in their late 30s/early 40s (40s married trajectory) and those in marital dissolution trajectories spent less time married. Furthermore, those in the unmarried trajectory had a mean number of years married as 0.1 for men and 0.4 for women. Although overall, members of this trajectory had never been married, this trajectory included individuals who had been married very briefly (on average 1 year) and, therefore, not likely to benefit from marriage.

As for the control variables, men in the three married trajectories had the lowest rates of childhood poverty, and men who experienced marital dissolution had the highest rates of depressed mothers, particularly those in the 20s married-unmarried trajectory. The highest rates of adolescent substance use and high school dropout were among those men who married late, remained unmarried, or experienced marital dissolution. For women, none of the comparisons were statistically significant, beyond mean number of years married.

Table 2 presents the bivariate association between marital trajectories and health risk behaviors. With our longitudinal data, we were able to assess impact along the life course by considering both young adult (age 32) and midlife (age 42) health behaviors. The male and female unmarried trajectories had some of the highest rates of these risk behaviors at both time points. The 20s and 30s married trajectories showed consistently the lowest rates of these outcomes. The 30s married-unmarried trajectory of men and the 20s married-unmarried trajectory of women showed consistently high rates of health risk behaviors in both young and mid-adulthood. Those women who married later in the life course did not achieve the lower rates of health risk behaviors in midlife as those who married earlier in the life course, with the exception of relatively low rates of binge drinking for late marrying women.

Table 2.

Bivariate Association Between Marital Trajectories and Health Risk Behaviors (N = 1,049)

| Marital Trajectory for Men (N = 503) | ||||||

| Consistently Married | Marital Dissolution | |||||

| Unmarried, N = 233 | 20s Married, N = 66 | 30s Married, N = 73 | 40s Married, N = 56 | 20s Married- Unmarried, N = 27 | 30s Married- Unmarried, N = 48 | |

| Young Adulthood (age 32) | ||||||

| Current smoking* | 59.4 | 37.1 | 39.3 | 47.9 | 58.2 | 64.3 |

| Binge drinking | 35.3 | 27.7 | 41.0 | 33.3 | 40.0 | 48.6 |

| Illegal drug use* | 34.4 | 15.1 | 18.3 | 23.0 | 25.2 | 35.1 |

| Midlife (age 42) | ||||||

| Current smoking† | 53.2 | 39.1 | 39.0 | 41.7 | 44.9 | 63.0 |

| Binge drinking† | 27.4 | 12.9 | 14.9 | 25.8 | 15.7 | 30.2 |

| Illegal drug use† | 24.8 | 17.4 | 11.2 | 8.9 | 23.2 | 25.9 |

| Marital Trajectory for Women (N = 546) | ||||||

| Consistently Married | Marital Dissolution | |||||

| Unmarried, N = 273 | 20s Married, N = 64 | 30s Married, N = 57 | 40s Married, N = 63 | 20s Married- Unmarried, N = 62 | 30s Married- Unmarried, N = 27 | |

| Young Adulthood (age 32) | ||||||

| Current smoking* | 54.6 | 25.4 | 33.5 | 44.5 | 57.6 | 45.0 |

| Binge drinking | 18.5 | 7.0 | 10.6 | 13.5 | 24.8 | 11.9 |

| Illegal drug use* | 24.1 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 14.1 | 23.2 | 7.5 |

| Midlife (age 42): | ||||||

| Current smoking* | 43.4 | 18.4 | 27.0 | 33.6 | 46.9 | 29.4 |

| Binge drinking† | 14.3 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 7.7 | 12.3 | 8.2 |

| Illegal drug use* | 16.9 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 14.7 | 17.6 | 6.1 |

p < .05.

p < .10 based on F-test statistics combining chi-square values across the 40 data sets using the SAS MACRO COMBCHI.

In Table 3, we compared the trajectories of those who were married at age 32 to the previously married trajectories (Model 1) and to those in the two yet to marry trajectories (Model 2). Although presented as separate models, the estimates were generated in a single analytic model with the married at age 32 group as the reference group. All models adjust for selection into marriage by controlling for early factors potentially affecting likelihood of marriage and health outcomes. We also take cohabitation into account. For Model 1 for men, we combined the two marital dissolution trajectories into the previously married group since both trajectories had primarily experienced marital dissolution by age 32. For women, we included only the early 20s married-unmarried trajectory in the previously married group, since the later dissolution trajectory of women were still married at age 32 and thus were placed in the married at age 32 group. For Model 2, the comparison with the yet to marry trajectories, we combined the unmarried and 40s married trajectories into a never married group since neither group had married by age 32. The reference group for both models was the married group, which included the 20s and 30s married trajectories for men and women, as well as the 30s married-unmarried trajectory for women since this trajectory was still married by age 32.

Table 3.

Marital Trajectories and Young Adult Health (Age 32): Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals (N = 1,049)

| Model 1: Previously Married at Age 32a Versus Married at Age 32b |

Model 2: Never Married by Age 32c Versus Married at Age 32b |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |||||

| Age 32 Health Outcomes |

OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Current smoking | 2.09* | 1.10, 3.99 | 2.68** | 1.36, 5.28 | 1.70* | 1.07, 2.70 | 2.06** | 1.31, 3.32 |

| Binge drinking | 1.42 | 0.54, 1.44 | 3.08* | 1.26, 7.55 | 0.88 | 0.75, 2.69 | 1.96† | 0.97, 3.95 |

| Illegal drug use | 1.97† | 0.95, 4.08 | 3.12* | 1.26, 7.73 | 1.97** | 1.11, 3.37 | 3.02** | 1.48, 6.19 |

Note: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Models use multiply imputed data and control for childhood socioeconomic status, having had a father present in the childhood household, maternal history of depressed mood, family history of chronic health problems, adolescent mental health, adolescent substance use, dropping out of high school, and cohabitation at young adulthood.

The “previously married at age 32” group includes the 20s married-unmarried trajectory and the 30s married-unmarried trajectory for men and the 20s married-unmarried trajectory for women.

The “married at age 32” group includes the 20s married and the 30s married trajectories for men and for women, as well as the 30s married-unmarried trajectory for women.

The “never married by age 32” group includes the unmarried trajectory and the 40s married trajectory for men and women.

p <.01.

p<.05.

p <.10.

As shown in Table 3, smoking, drinking, and illegal drug use were closely tied to marital trajectories in young adulthood (age 32). Both previously married and never married men and women had an increased risk of being a current smoker compared with those who were married. Similarly, men and women experiencing early marital dissolution and those yet to marry had 2 to 3 times the risk of past year illegal drug use than those married (this was only marginally significant for previously married men). Moreover, previously married women had 3.08 times the risk of binge drinking than married women. No association was found between marital history and young adult binge drinking among men.

In Table 4, we examined the association of marital patterns with health behaviors during midlife (age 42), adjusting for cohabitation at midlife as well as earlier risk factors. In Model 1, we compared the age 42 previously married group (20s and 30s married-unmarried trajectories) to an age 42 married group (20s, 30s, and 40s married). Model 2 compared the unmarried trajectory with the married group. Models 1 and 2 were run as a single analytic model with the married at age 42 group as the reference group. Model 3 is a separate analysis that compared earlier (20s, 30s) married trajectories to the later (40s) married trajectory.

Table 4.

Marital Trajectories and Midlife Health (Age 42): Odds Ratios, 95% Confidence Intervals, and p Values (N = 1,049)

| Model 1: Previously Married by Age 42a Versus Married at Age 42b |

Model 2: Never at Age 42c Versus Married at Age 42b |

Model 3: Later Marriedd Versus Early Marriede |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |||||||

| Age 42 Health Outcomes | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Current smoking | 1.61 | 0.88, 2.96 | 2.00* | 1.11, 3.62 | 1.51† | 1.01, 2.49 | 1.91** | 1.21, 3.03 | 0.96 | 0.48, 1.92 | 1.68 | 0.80, 3.54 |

| Binge drinking | 1.18 | 0.54, 2.59 | 2.27 | 0.78, 6.55 | 1.41 | 0.81, 2.47 | 2.48* | 1.06, 5.78 | 1.77 | 0.74, 4.24 | 2.08 | 0.49, 8.79 |

| Illegal drug use | 2.05† | 0.96, 4.38 | 1.99 | 0.79, 5.03 | 2.14* | 1.10, 4.14 | 2.25* | 1.08, 4.71 | 0.52 | 0.15, 1.77 | 4.68* | 1.20, 18.24 |

Note: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Models use multiply imputed data and control for childhood socioeconomic status, having had a father present in the childhood household, maternal history of depressed mood, family history of chronic health problems, adolescent mental health, adolescent substance use, dropping out of high school and cohabitation at midlife.

The “previously married at age 42” group includes the 20s married-unmarried and the 30s married-unmarried trajectories for men and women.

The “married at age 42” group includes the 20s married, the 30s married, and the 40s married trajectories for men and women.

The “never married by age 42” group is the unmarried trajectories for men and for women.

The later married group is the 40s married trajectories for men and women.

The early married group includes the 20s married and the 30s married trajectories for men and women.

p <.01.

p <.05.

p < .10.

Controlling for factors affecting the likelihood of marriage and health outcomes, marital patterns continued to be related to health behaviors in midlife. Both previously (OR = 2.00) and never married (OR = 1.91) women had about twice the risk of being a current smoker at age 42 compared with married women. Never married women had 2.48 times the risk of binge drinking and 2.25 times the risk of illegal drug use of married women. Finally, previously (OR = 2.05) and unmarried men (OR = 2.14) had over twice the risk of midlife drug use compared with married men. In terms of marital timing (Model 3), findings showed no statistically significant differences between men who married early and remained married and those who married later in the life course. For women, we saw an increased risk of unhealthy behaviors among those who married later, with only past year illegal drug use reaching statistical significance (OR = 4.68, p= .03).

Discussion

Using a trajectory analysis, we identify six distinct groups of men and of women who vary in marital status, timing, and stability. These trajectories show great heterogeneity with regard to marriage among this cohort of urban African Americans followed from age 6 to 42. Some men and women establish stable marriages early in the life course, whereas others experience marital dissolution, marry later in the life course, or are among the large proportion of the cohort remaining unmarried into midlife. This large unmarried group is in contrast to marriage rates of other populations of Americans. In a comparison of the rates of White and African American women born from 1960 to 1964 (the Woodlawn cohort was born in 1960), Goldstein and Kenney (2001), using data from the Current Population Survey, projected that 93% of White women are expected to marry, whereas only 64% of African American women are expected to marry. As we show in our analyses, marriage is protective for the African Americans we studied. However, as of midlife, almost half of the men and women belong to the never married trajectory and so they are not able to benefit from the “marriage protection.”

Although not surprising given the demographics of this cohort (urban, low income), and the national trends among African Americans to remain unmarried and experience high rates of marital separation (Bryant & Wickrama, 2005; Tucker & Mitchell-Kernan, 1995), it is concerning to find so few maintaining stable marriages into midlife. A little over a third of men and women are classified into a married trajectory in midlife, and likely some of these marriages will end. Such low rates of marital stability may contribute to health disparities between African American and White populations in the United States as indicated by this study’s findings linking consistent marriage with decreased risk of unhealthy behaviors.

Patterns found are quite similar for men and women, with minor exceptions, such as the differences in size between the two married-unmarried trajectories. More than twice as many women are classified in the 20s married-unmarried trajectory (11.4%) as men (5.4%). Thus, early marrying women may be more vulnerable to marital dissolution than men and potentially could be a target of the many marital promotion efforts. Also, the timing varies between the male and female married-unmarried trajectories, with women marrying at younger ages than men. The marital dissolutions for men occur earlier in the life course than for women, reaffirming the importance of considering patterns by gender.

As analyses show, after taking selection into marriage into consideration, married African American men and women engage in fewer health risk behaviors than unmarried individuals in both young adulthood and midlife. The increased risk is relatively consistent for those who are in the never married trajectories and those who are in the married-unmarried trajectories. Thus, marital dissolution seems to have a similar negative impact on health as remaining unmarried. These results build on literature suggesting marriage as an avenue to promote health in the African American community (Blackman, Clayton, Glenn, Malone-Colon, & Roberts, 2005; Fothergill et al., 2009), at least with regard to substance use behavior.

However, as our findings show, the benefits of marriage only translate to those individuals who remain continuously married. This finding can begin to speak to the mechanisms of change in health behaviors associated with marriage. Direct supervision and a change in routine activities may be driving the association (Umberson, 1992) as opposed to an intrinsic change in self or a long-lasting change in the propensity to engage in risky health behaviors, since this more permanent change would be evidenced by the benefits of marriage extending to those in the previously married groups. Although we had hypothesized that timing of marriage might have an additional impact on health risk behaviors, we find little evidence of such an impact. Those who marry later seem to fare as well by midlife as those who marry early and stay married. We find only one difference in midlife between those in the late and the earlier marrying groups. The later marrying women have an increased risk of past year illegal drug use at age 42 compared with those in the early married group. This difference could be attributed to a differential impact of marriage on early compared with later marrying (i.e., marital timing) or may have to do with the length of time in a marriage (i.e., marital duration), as previous work has found health benefits to accumulate over time (Lillard & Waite, 1995). Those in long-term stable marriages may derive increased benefit compared with those more recently married, and over the long-term no differences may be observed. Further work is necessary to understand how marital timing, duration, and other marital qualities influence health.

In terms of gender differences, the major difference relates to binge drinking. Although previous work has found that marriage may reduce binge drinking for both men and women (Wood, Goesling, & Avellar, 2007), we find no effect for men. We speculate that since binge drinking for this community cohort of men is common overall, it may be seen as an acceptable occasional behavior for a married man. More research is necessary to confirm this finding and determine if marriage affects other types of problematic drinking behaviors, such as frequency of binge drinking or meeting alcohol disorder criteria among low income African Americans.

There are a number of considerations that should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. Although the marital trajectories capture complex patterns over time, they provide less insight into the quality of marriages and marital satisfaction, which has been found to be an important moderating factor when examining health consequences (Umberson & Williams, 2005; Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, 2006). Although we can assume those in trajectories experiencing marital dissolution have less satisfaction and lower quality marriages (very few cohort members were widowers), we were not able to study quality directly. It is important for future research to simultaneously examine marital satisfaction, stability, duration, and timing among urban African Americans. Additionally, although we would have liked to examine the intricacies of marital patterns among the individual trajectory groups (e.g., comparing 20s to 30s to 40s marriage), our sample size did not allow us to do so. Instead, it was necessary to combine trajectories when it made sense conceptually. Although analyses validate the combination of trajectories, they limit definitive conclusions about the timing of marital dissolution, in particular, on health. Although our results (not shown) suggest that for this population whether marriages dissolve in the 20s or in the 30s does not affect these health risk behaviors, more work is necessary. Furthermore, we were unable to study cohabitation in any depth because of low rates of cohabitation and a lack of data on the stability of cohabitating relationships. Though previous work has found that cohabitation had less of an effect on reducing health risk behaviors compared with marriage (e.g., Duncan et al., 2006; Wu, Penning, Pollard, & Hart, 2003), the benefits of cohabitation among African Americans are still relatively underinvestigated. Finally, we relied on covariate adjustment to take into account selection into marriage and control for a wide range of risk factors, including deviant behavior, education, and family background. Yet there is the risk that unobserved covariates could explain the relationships we found.

As we strive to understand the racial disparities in health, the relationship of health risk behaviors and marital trajectories among African Americans is clearly an area in need of further research. African Americans who maintained a stable marital pattern, regardless of timing, after controlling for selection into marriage, were at a decreased risk of substance use. Therefore, policies that promote marriage, such as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service’s Healthy Marriage Initiative (Hawkins, Wilson, Ooms, Malone-Colon, & Cohen, 2009; Myrick, Ooms, & Patterson, 2009), need to prioritize efforts on creating long-term, healthy marriages in order to have any potential impact on health. The impact of other policies and structures that are not focused on marriage but that may unintentionally discourage marriage among low-income populations (welfare, public housing rules, marriage costs) should be considered in policy discussions. Contextual circumstances, such as economics and employment opportunities, are also known to be related to the potential for marriage and may be targets both in further research and for increasing the likelihood of marriage.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics by Martial Trajectory for Men and Women (N = 1,049)

| Marital Trajectory | ||||||

| Men (N = 503) | Unmarried, N = 233 | 20s Married, N = 66 | 30s Married, N = 73 | 40s Married, N = 56 | 20s Married- Unmarried, N = 27 | 30s Married- Unmarried, N = 48 |

| Mean number of years married* | 0.1 | 16.8 | 13.6 | 5.8 | 5.0 | 6.5 |

| Mothers’ years of schooling | 10.5 | 10.7 | 10.9 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 10.0 |

| Childhood poverty | 60.7% | 49.3% | 41.5% | 50.7% | 59.3% | 54.2% |

| Father present in childhood* | 38.6% | 47.7% | 62.3% | 41.1% | 48.2% | 50.0% |

| Mother’s depressive symptoms* | 14.1% | 20.8% | 9.9% | 12.7% | 39.9% | 23.3% |

| Family chronic health problems | 24.5% | 27.6% | 17.8% | 17.9% | 14.8% | 31.1% |

| Poor adolescent mental health | 50.2% | 38.5% | 42.9% | 53.4% | 46.3% | 52.3% |

| Heavy adolescent substance use* | 67.8% | 60.6% | 53.4% | 75.0% | 81.5% | 77.1% |

| High school dropout* | 37.3% | 18.2% | 19.2% | 28.9% | 33.3% | 35.4% |

| Cohabitation at age 32* | 15.8% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 17.3% | 9.3% | 2.3% |

| Cohabitation at age 42* | 15.5% | 2.7% | 0.9% | 3.6% | 15.7% | 8.4% |

| Women (N = 546) | Unmarried, N = 273 | 20s Married, N = 64 | 30s Married, N = 57 | 40s Married, N = 63 | 20s Married- Unmarried, N = 62 | 30s Married- Unmarried, N = 27 |

| Mean number of years married* | 0.4 | 19.7 | 11.4 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 9.9 |

| Mothers’ year of schooling | 10.7 | 10.6 | 10.8 | 10.9 | 10.7 | 10.4 |

| Childhood poverty | 52.7% | 49.0% | 47.4% | 44.4% | 46.8% | 56.7% |

| Father present in childhood | 45.1% | 56.3% | 49.1% | 50.8% | 44.0% | 48.2% |

| Mother’s depressive symptoms | 16.2% | 15.9% | 11.2% | 17.6% | 21.9% | 18.9% |

| Family chronic health problems | 25.7% | 31.3% | 24.6% | 20.6% | 13.7% | 33.3% |

| Poor adolescent mental health | 58.6% | 52.5% | 53.7% | 55.1% | 56.5% | 55.9% |

| Heavy adolescent substance use | 57.5% | 48.4% | 50.9% | 58.7% | 58.7% | 40.7% |

| High school dropout | 24.0% | 15.7% | 16.4% | 21.7% | 21.9% | 15.2% |

| Cohabitation at age 32* | 8.6% | 0.4% | 2.1% | 8.7% | 5.5% | 0.1% |

| Cohabitation at age 42* | 10.2% | 3.3% | 0.4% | 3.0% | 3.8% | 1.2% |

p < .05 based on F-test statistics combining chi-square values across the 40 data sets using the SAS MACRO COMBCHI. Mean number of years married and mother’s years of schooling relied on an ANOVA (F statistic) for computing statistical significance.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Shephard Kellam, Ms. Jeannette Branch (now deceased), the Woodlawn Advisory Board, and the Woodlawn Study participants for their support and involvement with the study over many years.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health (Grant Numbers R01DA022366-01A2 and R01DA 026863-01).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Anderson E. Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York, NY: W. W. Norton; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn WG, Thorton A. The influence of parental resources on the timing of the transition to marriage. Social Science Research. 1992;21:261–285. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Bryant AL, Merline AC. The decline of substance use in young adulthood: Changes in social activities, roles, and beliefs. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: The impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 137–173. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman L, Clayton O, Glenn N, Malone-Colon L, Roberts A. The consequences of marriage for African Americans: A comprehensive literature review. New York, NY: Institute for American Values; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. First marriage dissolution, divorce, and remarriage: United States. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics. 2001;323:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CH, Adams RG, Kellam SG. A longitudinal study of teenage motherhood and symptoms of distress: The Woodlawn Community Epidemiological Project. Research in Community and Mental Health. 1981;2:183–213. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, Wickrama KAS. Marital relationships of African Americans: A contextual approach. In: McLoyd V, Hill N, Dodge KA, editors. African American family life: Ecological and cultural diversity. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 111–134. [Google Scholar]

- Carlin JB, Galati JC, Royston P. A new framework for managing and analyzing multiply imputed data in Stata. Stata Journal. 2008;8:49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A. Marriage and marital dissolution among Black Americans. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1998;29:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. Should the government promote marriage? Contexts, American Sociological Association. 2003;2:22–29. Fall. [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Juon HS, Green KM, Robertson J, Fothergill K, Ensminger M. Educational achievement and early school behavior as predictors of alcohol-use disorders: 35-year follow-up of the Woodlawn Study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:75–85. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty EE, Green KM, Ensminger ME. The impact of adolescent deviance on marital trajectories. Deviant Behavior. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2010.548303. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G, Wilkerson B, England P. Cleaning up their act: The effects of marriage and cohabitation on licit and illicit drug use. Demography. 2006;43:691–710. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupre ME, Beck AN, Meadows SO. Marital trajectories and mortality among US adults. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170:546–555. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupre ME, Meadows SO. Disaggregating the effects of marital trajectories on health. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28:623–652. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. Suicide. New York, NY: Free Press; 1951. (Original work published 1897) [Google Scholar]

- England P, Shafer EF. Everyday gender conflicts in low-income couples. In: England P, Edin K, editors. Unmarried couples with children. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2007. pp. 55–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME, Juon HS, Fothergill KE. Childhood and adolescent antecedents of substance use in adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:833–844. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill KE, Ensminger ME, Green KM, Thorpe RJ, Robertson J, Kasper JD, Juon HS. Living arrangements during childrearing years and later health of African American mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family Health. 2009;71:848–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryar CD, Hirsch R, Eberhardt MS, Yoon SS, Wright JD. Hypertension, high serum total cholesterol, and diabetes: Racial and ethnic prevalence differences in U.S. adults, 1999–2006. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief. 2010;36:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N. Marriage selection and mortality patterns: Inferences and fallacies. Demography. 1993;30:189–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JR, Kenney CT. Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecast of first marriage for US women. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:506–519. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Lee H, DeLeone FY. Marriage and health in the transition to adulthood: Evidence for African Americans in the Add Health Study. Journal of Family Issues. 2010;31:1106–1143. doi: 10.1177/0192513X10365823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AJ, Wilson RF, Ooms T, Malone-Colon L, Cohen L. Recent government reforms related to marital formation, maintenance, and dissolution in the United States: A primer and critical review. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy. 2009;8:264–281. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AV, White HR. Becoming married, depression, and alcohol problems among young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991;32:221–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AV, White HR, Howell-White S. Becoming married and mental health: A longitudinal study of a cohort of young adults. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:895–907. [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Assessing longitudinal change in marriage: An introduction to the analysis of growth curves. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:1091–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Branch JD, Agrawal K, Ensminger ME. Mental health and going to school. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Koball H, Moiduddin E, Henderson J, Goesling B, Besculides M. What do we know about the link between marriage and health? Journal of Family Issues. 2010;31:1019–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. The relations between reported well-being and divorce history, availability of a proximate adult, and gender. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lane SD, Keefe RH, Rubinstein RA, Levandowski BA, Freedman M, Rosenthal A, Czerwinski M. Marriage promotion and missing men: African American women in a demographic double bind. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2004;18:405–428. doi: 10.1525/maq.2004.18.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson JH, Holman TB. Premarital predictors of marital quality and stability. Family Relations. 1994;43:228–237. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Rothbard JC. Alcohol and the marriage effect. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement. 1999;13:139–146. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA, Panis CWA. Marital status and mortality: The role of health. Demography. 1996;33:313–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA, Waite LJ. Till death do us part: Marital disruption and mortality. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;100:1131–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Lopoo LM, Western B. Incarceration and formation and stability of marital unions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:721–734. [Google Scholar]

- Merline AC, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Substance use among adults 35 years of age: Prevalence, adulthood predictors, and impact of adolescent substance use. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:96–102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the US. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2000. 2004;291:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudar P, Kearns JN, Leonard KE. The transition to marriage and changes in alcohol involvement among black couples and white couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:568–576. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrick M, Ooms T, Patterson P. Healthy marriage and relationship programs: A promising strategy for strengthening families. 2009 Nov; (National Healthy Marriage Resource Center Discussion Paper). Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/healthymarriage/pdf/MarriageProgramsPromisingStrategies_87FB.pdf.

- Nagin DS. Group-based modeling of development over the life course. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2004;53(5) [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2009: With special feature on medical technology. Hyattsville, MD: Author; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Kellam SG. Measurement of psychological well-being of adolescents: The psychometric properties and assessment procedures of the how I feel. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1977;6:229–247. doi: 10.1007/BF02138937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EB. African American marriage in the 20th century. Family Process. 2002;41:269–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.41206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleis JR, Lucas JW, Ward BW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey. Vital Health Statistics, 2008. 2009;10:1–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins CA, Martin SS. Gender, styles of deviance, and drinking problems. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34:302–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: Further update of ice, with an emphasis on categorical variables. Stata Journal. 2009;9:466–477. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York, NY: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer EF. The effect of marriage on weight gain and propensity to become obese in the African American community. Journal of Family Issues. 2010;31:1166–1182. [Google Scholar]

- South S. Racial differences and the desire to marry. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1993;53:357–370. [Google Scholar]

- South SJ. The variable effects of family background on the timing of first marriage: United States, 1969–1993. Social Science Research. 2001;30:606–626. [Google Scholar]

- Stutzer A, Frey BS. Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? Journal of Socio-Economics. 2006;35:326–347. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker MB, Mitchell-Kernan C, editors. The decline in marriage among African Americans. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Gender, marital status, and the social control of health behavior. Social Science & Medicine. 1992;34:90–917. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90259-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Williams K. Marital quality, health, and aging: gender equity? Journal of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2005;60:S109–S113. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Williams K, Powers DA, Liu H, Needham B. You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:1–16. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ. Does marriage matter? Demography. 1995;32:483–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ, Neckerman K. Poverty and family structure. The widening gap between evidence and public policy issues. In: Danziger S, Weinberg D, editors. Fighting poverty. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1986. pp. 232–259. [Google Scholar]

- Wood R, Goesling B, Avellar S. The effects of marriage on health: A synthesis of recent research evidence. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Penning MJ, Pollard MJ, Hart R. “In sickness and in health”: Does cohabitation count? Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:811–838. [Google Scholar]