Abstract

Background

The lack of patient engagement in quality improvement is concerning, given increasing recognition that this participation may be essential for improving both quality and safety. As part of an enterprise-wide initiative to redesign primary care at the University of Wisconsin Health System, interdisciplinary primary care teams received training in patient engagement.

Methods

Organizational stakeholders held a structured discussion and used nominal group technique to identify the key components critical to fostering a culture of patient engagement and critical lessons learned. These findings were augmented and illustrated by review of transcripts of two focus groups held with clinic managers and 69 interviews with individual microsystem team members.

Results

From late 2009 to early 2014, 47 (81%) of 58 teams have engaged patients in various stages of practice improvement projects. Organizational components identified as critical to fostering a culture of patient engagement were alignment of national priorities with the organization's vision guiding the redesign, readily available external experts, involvement of all care team members in patient engagement, integration within an existing continuous improvement team development program, and an intervention deliberately matched to organizational readiness. Critical lessons learned were the need to embed patient engagement into current improvement activities, designate a neutral point person(s) to navigate organizational complexities, commit resources to support patient engagement activities, and plan for sustained team-patient interactions.

Conclusions

Current national health care policy and local market pressures are compelling partnering with patients in efforts to improve the value of the health care delivery system. The UW Health experience may be useful for organizations seeking to introduce or strengthen the patient role in designing delivery system improvements.

Redesign of primary care delivery is a national priority in the United States,1 given that health systems anchored in primary care have lower costs and better quality.2,3 Models for redesigning primary care, including the patient-centered medical home,4,5 recognize both care teams and patients as critical stakeholders because of their interactions at the front lines of care.6

Concurrently, there is an increasing emphasis on involving patients because of the recognition that patient engagement is essential for improving quality and safety. For example, the National Committee for Quality Assurance's medical home certification program stipulates that the “practice has a process for involving patients and their families in its quality improvement activities.”7 The final rule of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Accountable Care Organization Shared Savings Program similarly reflects a patient-centered focus through the requirement that beneficiaries participate in accountable care organization governance.8

Primary care transformation efforts have been criticized for not involving patients in quality improvement (QI).9 The literature is surprisingly lacking in robust descriptions of health care organizations’ efforts to engage patients. Instead, investigators have focused more broadly on organizational factors as facilitators and barriers to achieving patient-centered care, such as incorporating patient representatives on various boards and committees.10–12 In a 2010 national survey of patient-centered medical home practices in 2010, responses from 112 (in 22 states) of the 238 practices invited indicated that lack of knowledge and resources about successful models of patient involvement activities were significant limitations to patient engagement. Responses also indicated a specific need for templates, how-to-guides, and successful practices was also noted in this survey.13

In this article, we describe key organizational components critical to fostering a culture of patient engagement. We report organizational lessons learned from our experience in engaging patients in an enterprise-wide program to develop primary care teams. This effort is part of a large-scale primary care transformation, “Partnering with Patients,” at University of Wisconsin Health (UW Health), an organizationally complex academic health system. The complexity of the health system is exemplified by ownership and management of these primary care clinics by three separate entities and differing regulatory requirements and workforce considerations that occur among hospital, medical school, and physician group-operated clinical sites. This lack of system-level integration and management, which is characteristic of much of health care in the United States, posed unique challenges but has also generated many valuable and generalizable learnings. Our experience should be useful to other efforts intended to introduce or strengthen the patient role in designing delivery system improvements in a variety of organizational settings.

Methods

Definitions

We define patient engagement as “an active process of ensuring that our patients’ experience, wisdom and insight are infused into individual care and the design and refinement of our care systems.”14 For the purposes of this article, the term “patient engagement” represents both patient and family engagement. We describe a program in which the focus of engagement was on practice redesign at the microsystem level. The microsystem is defined as a small care unit consisting of a care team, their panel of patients, and their core processes that produce the patterns and norms of this unit.15 As was the intent here, engaging patients in practice redesign should be patient-centered, an approach that is grounded in “mutually beneficial partnerships among health care providers, patients, and families”16 characterized by respect and dignity, affirming and useful information sharing, active participation in care and decision making, and collaboration at the policy and program level.

Context

The UW Health System

UW Health is a public academic health system consisting of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, and the University of Wisconsin Medical Foundation. In the UW Health primary care delivery system— one of the largest academic medical centers in the United States—368 primary care providers, including faculty physicians; advance practice clinicians (physician assistants and nurse practitioners); and residents from general pediatrics, family medicine, and general internal medicine, care for approximately 287,000 medically homed patients. Thirty-three primary care clinics in Dane County, which includes the city of Madison, and an additional 8 clinics in surrounding counties serve this population. Primary care physicians constitute 16% of the 1,356 members of the University of Wisconsin Medical Foundation practice plan, the largest medical group in Wisconsin.

The UW Health System Patient-Centered Primary Care Redesign Initiative

In 2008, UW Health System organizational leaders identified the redesign of the primary care delivery system as a key priority in response to an alarming attrition of primary care providers and suboptimal accessibility, service, and quality metrics. Initial steps included the creation of an enterprisewide vision of a transformed primary care delivery system using multidisciplinary teams in a participatory process. Drafts of this vision were provided to hundreds of providers and staff across UW Health primary care clinics for input and validation, thereby increasing the likelihood that the UW Health primary care vision would reflect the attitudes, beliefs, and aspirations of frontline teams. The vision statement incorporated principles of patient-centered care, noting that “patient-driven improvements to primary care will be achievable, affordable, and flexible” and that “a culture of respect and trust will be the basis of a primary care team that fully empowers patients.”17

UW Health Primary Care Redesign Initiative leaders recognized that any attempt to transform the delivery of primary care must address all four Institute of Medicine-described levels of the health system—patient, microsystem, organization, and environment.18,19 They strategically decided to initially focus on the clinical microsystem to develop the capacity of frontline care teams to improve care while delivering care. Berwick characterized the clinical microsystem as “where the work happens; it is where the ‘quality’ experienced by the patient is made or lost.”19(p. 84) By focusing on the microsystem level, leaders of the redesign initiative believed that they could create a frontline culture of change with tangible improvements.

Team-based Training Program

A training program to develop primary care microsystem teams was implemented in September 2009. Recruitment of microsystem teams and clinics was based on establishing a mutual set of expectations among organizational program leadership, clinic managers, and physician leaders. The teams were asked to develop a communication plan to update the whole clinic and “disseminate the changes and improvements made during the pilot to the rest of your clinic.” Other methods were employed to inform and engage the clinic included presentations at staff meetings, visibility boards, clinic newsletters, and e-mail communiqués.

Training occurred in cohorts consisting of 8 to 10 care teams. Each care team was composed of frontline staff (usually a physician, receptionist, medical assistant, nurse, and physician assistant or nurse practitioner) who typically worked together at a clinic site serving a panel of patients. Program participants received four to six months of intensive process improvement education and support from an improvement coach. The training curriculum consisted of four learning sessions, in which microsystem teams, clinic managers, and clinic medical directors from all the sites gathered to discuss their improvement work, develop action plans, and celebrate progress. Clinic leaders, providers, and staff informally interacted to share ideas and create networks of shared interest. Those teams that successfully engaged patients told their stories and, on two occasions, patients attended and provided their own accounts about the value of being part of team improvement work. The contributions and enthusiasm of patients appeared to be influential in changing attitudes and reinforcing the importance of patient participation in delivery system redesign.

For each cohort, this intensive training phase was followed by four to six months of progressively decreasing coaching support to consolidate improvement skills and knowledge. From September 2009 through July 2014, 58 interdisciplinary microsystem teams, in six cohorts, completed this educational program. Thirty-three (80%) of 41 clinics now have at least one trained microsystem team.

In support of the patient-centered vision, redesign initiative leaders recognized that patients are central to all processes and could provide valuable contribution to continuous improvement efforts. Lacking experience, skills or tools to engage patients in local team improvements, UW Health collaborated with patient engagement experts at the Center for Patient Partnerships to develop a program for microsystem teams to engage patients in process improvement at the front lines of care.19 The Center for Patient Partnerships is an interdisciplinary patient advocacy center of the University of Wisconsin Schools of Law, Medicine & Public Health, Nursing, and Pharmacy. The Center developed a patient engagement training program that included coach and team member curricula, education and step-by-step how to guides, tools and templates. Sidebar 1 lists resources, which are available online.20 Patient input helped focus and prioritize teams’ aims, as well as generate and test change ideas.

Sidebar 1.

Patient Engagement Training Program Resources Available Online*

| Patient Engagement Toolkit for Team Members |

| 1. Co-creating Materials |

| 2. Using this Toolkit |

| 3. Patient Engagement: A Definition and Context |

| 4. Principles of Engagement |

| 5. Levels and Methods of Engagement |

| 6. Engagement Essentials – The “How To” Worksheet |

| a. Getting Started: A Process of Discernment |

| b. Matching the Engagement Method with Your Projects |

| c. Defining the Job |

| d. Identifying and Recruiting the Best Patients for the Job |

| e. Inviting Patients: Obtaining a Mutually Beneficial Match |

| f. Creating a Welcoming Environment |

| g. Celebrating Engagement Successes |

| h. Capturing Lessons |

| 7. Appendices—including tools and sample materials |

| 8. References |

|

Patient Partner Welcome Packet: Quality Improvement Volunteering |

| 1. Welcome! |

| 2. Value of Being a Patient Partner |

| 3. Patient Engagement Program Philosophy |

| 4. Quality Improvement Goals |

| 5. Example of Team-Based Quality Improvement Work |

| 6. Tips for Successful Service |

| 7. Resources |

Materials available at Health Innovation Program, the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. HIPxChange. http://hipxchange.org/PatientEngagement.

The organizational commitment of resources annually was $19,000, which included engaging The Center for Patient Partnerships, coaching support, food and materials for quarterly learning sessions, and a small budget to support patient travel.

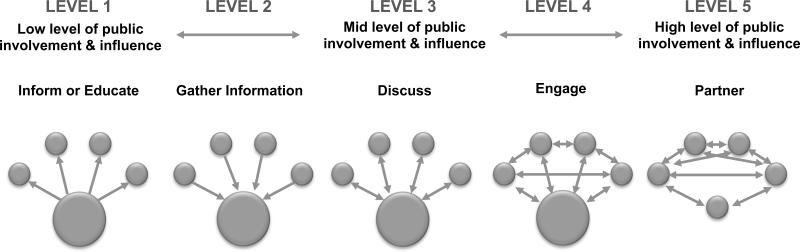

Adaptation of a Patient Engagement Framework

Critically important to the patient engagement effort was the adaptation of a framework for public involvement in health policy decision making20 (Figure 1). Today, frameworks and tool kits are more readily available but, we believe, still do not offer the level of practical, ready-to-implement steps for team-based engagement activities created for our program.21,22 This framework, which we adapted by exchanging the words public with patient, describes progressive levels of patient engagement. At higher levels of engagement the flow of information is bi-directional, and at the highest level patients are depicted as having equal involvement and power with the system by the equalized size of the circles. These range from informing patients of QI activities (Level 1) to including patients as equal members of the team who attend meetings and actively participate in improvement projects (Level 5). Table 1 provides detailed examples of team activities that occurred at each level.

Figure 1. Patient Engagement Levels.

Arrows depict the flow of information between the health system and providers (depicted by the larger circle) and patients (depicted by the smaller circles). At Level 1, the organization communicates with stakeholders. At Level 2, the organization gathers information from stakeholders. At Level 3, the organization communicates with and gathers information from stakeholders. At Level 4, stakeholders are engaged by the organization and also engage each other. At Level 5, circles are equivalent as both the public stakeholders and the organization are partners. Reproduced with permission from the Minister of Health, 2013. Health Canada, Corporate Consultation Secretariat, Health Policy and Communications Branch. Health Canada Policy Toolkit for Public Involvement in Decision Making. 2000. (Updated: Sep 14, 2006.) Accessed Oct 14, 2014. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/pubs/_public-consult/2000decision/index-eng.php.

Table 1.

Patient Engagement Activities Engaged in by Teams

| Patient Engagement Level | Sample Activities |

|---|---|

| Level 1: Inform/Educate | Teams hang posters in waiting areas to notify patients of patient engagement opportunities and quality improvement efforts, and all communications are branded with the “Partnering with Patients” logo. |

| Level 2: Gather | In the belief that patients are concerned about wait times, a team surveys patients, only to learn that patients are willing to wait; waiting suggests to them that the physician will also spend more time with them if needed. |

| Level 3: Discuss | A team uses a variety of methods, such as calling some patients and inviting others to a team meeting, to learn more about the specific needs of patients with controlled and uncontrolled diabetes. |

| Level 4: Involve | A team in a clinic that is relocating convenes a Patient Advisory Panel to meet monthly for six months during the transition. In discussion with the panel, the team learns that patients do not realize the clinic is moving but rather think it is closing (given the “for sale” sign on the building) and also gains valuable feedback on the new self-rooming plan in the new clinic. |

| Level 5: Partner | A team decides to invite a patient to join the team and be an active participant at team meetings, resulting in more thoughtful conversations about patients, which in turn leads to a shift in culture in that the team now thinks about patients as partners in care rather than external customers. |

Initially, the level of engagement was left to the discretion of the microsystem teams, who considered their level of readiness and goals. Some teams were eager and ready to engage patients at a range of levels, while others were struggling to see the value in engaging patients or were focused on developing their own team skills and capabilities. During the third through fifth cohorts, however, patient engagement was defined as an expectation, and teams were encouraged to engage patients at least at the level of “Discuss” (Level 3). Coaches supported teams on an individual basis by identifying opportunities for patient engagement and suggesting methods.

Forty-seven primary care teams of the 58 teams that completed microsystem training have engaged patients in various stages of practice improvement projects. Although patient engagement was becoming a formal deliverable in the Microsystem program, as well as overall UW Health organizational culture, 14 teams failed to see the value in engaging patients in QI efforts and declined to participate in this aspect of the program. The teams that did not engage generally also struggled with participation in QI activities because of competing priorities (for example, electronic health record implementation). However, our collective experience with the remaining 47 teams that successfully engaged patients has deepened our conviction that involving patients in the planning, development, and testing of clinical improvements is essential for improving quality and safety.

Organizational Stakeholder Discussion

A one-hour organizational stakeholder discussion was held on March 8, 2013 to determine: (1) the key organizational components necessary for patient involvement with primary care teams and (2) the critical organizational lessons learned through this process.

The nine participating stakeholders were clinical vice chairs of the three primary care departments; leaders of the quality department, leaders of the Microsystem training program; and directors of the Center for Patient Partnerships. These individuals were responsible for program development, implementation, and evaluation. For each of these two questions, a nominal group technique was used.23 First, participants independently wrote down their ideas. They then broke into two groups to discuss their ideas and create a unified list. The two groups, in a discussion that was audiorecorded, then discussed these lists and created a single, comprehensive list by eliminating duplicate items and combining items into categories. Finally, all nine participants used dots to vote and prioritize which components and lessons they considered the most important.

Feedback from Clinic Leadership and Microsystem Team Members

During the first two cohorts of the Microsystem training program, two one-hour focus groups were held in 2011 with clinic managers to determine lessons learned to date from the Microsystem program, which were recorded and transcribed. In addition, six teams from the first cohort and five teams from the second cohort were selected by organizational leaders from the program to be interviewed at their clinic site towards the end of the formal training period. Teams were selected to maximize variation (for example, by specialty, location). Between 2010 and 2011, 69 team members were interviewed individually about their perceptions of the program. The transcriptions of these interviews were reviewed for themes and quotations that could augment or illustrate findings at the organizational stakeholder level.

Results

Key Organizational Components

Five components were identified as being key for fostering a culture of patient engagement: (1) alignment of the organization's vision guiding the redesign with national patient engagement priorities, (2) readily available external experts, (3) involvement of all care team members in patient engagement, (4) integration within an existing continuous improvement team development program, and (5) an intervention deliberately matched to organizational readiness. We now describe these components.

1. Alignment of the UW Health Vision That Guided the Redesign with National Priorities

The national context (for example, patient-centered medical home) highlighted the desirability and urgency of engaging patients in primary care redesign strategies. The timing of the organizations’ Primary Care Redesign Initiative largely coincided with these national efforts. Consistent with this national climate, patient engagement was determined to be a priority, as reflected in the initiative's name, “Partnering with Patients”—which aligned with the priorities of frontline teams. One receptionist commented, “We have the same goal. We want to make it better for patients. Patients pay our paychecks. We are not here for ourselves.”

2. Readily Available External Experts

The Center for Patient Partnerships was a critical factor in implementing the patient engagement program in our organization, which had historically not had a robust infrastructure supporting patient-centered activities. Center staff's expertise and knowledge enabled them to suggest practical tactics for engaging patients, offer consultation with system leaders, and provide training for frontline care teams and improvement coaches. They also developed accessible how-to guides20 and introduced the Patient Engagement Framework, which facilitated communication about goals and achievements. Furthermore, their specialty legal support (the faculty involved were lawyers) addressed clinical provider and staff concerns about the organizational risks of including patients in QI. Finally, they provided significant encouragement to the organization during this period of culture change.

3. Involvement of All Care Team Members in Patient Engagement

Microsystem training engaged providers and staff with a less physician-centric approach that allowed the whole team to participate in care improvements, including nonclinical staff. One clinic manager explained: My team, I do not think, is driven by my provider as much as it is the staff. They have seen by doing the things they're doing that they are helping to create the new model that we are going to have .... they feel very vested, they feel very, I think “empowered” is a good word for them.

4. Integration within an Existing Continuous Improvement Team Development Program

The microsystem model and curriculum provided a preexisting program that was readily expanded to include patient engagement training. The well-developed structure of the microsystem program—which included dedicated time for teams to learn and a coach to support and facilitate team learning—complemented the clear patient engagement steps provided by the tool kits and made it easier to incorporate patient engagement into busy clinical environments. In the words of a receptionist, “We feel it's a gift of time. We feel it being so productive- it's not a detriment to us. The weekly meetings are wonderful.”

5. Intervention Deliberately Matched to Organizational Readiness

The organization was strategic in deploying engagement interventions that matched organizational readiness. Introducing patient engagement as an expansion of the microsystem training program prevented an overextension of resources and was calibrated to match the tolerance of leaders for organizational change. Then, when patient engagement was first introduced to teams, experts at the Center for Patient Partnerships developed and deployed a strategy to address legal and policy issues that were raised. For example, there were concerns as to how patients would perceive the internal workings of the organization and about other related issues of confidentiality. The Center for Patient Partnerships worked with UW Health to create a confidentiality agreement for participating patients and targeted educational materials for participating teams that addressed common myths about barriers to patient engagement, such as the misconception that personal health information doesn't need to be disclosed to engage patients. These strategies served to assuage leadership, provider, and staff concerns.

Critical Lessons Learned

Through this work, the organization learned about the need to specifically address barriers to patient engagement in primary care redesign. One specific barrier was a perceived lack of time to do this work, with patient engagement was an additional component added to a QI program that was already perceived as additional work for busy clinicians. Another barrier was participants’ lack of clarity about organizational policies and procedures regarding confidentiality concerns (for example, HIPAA24), the status of patient partners (for example, are they volunteers?), and reimbursement for nominal engagement expenses. Finally, participants generally expressed a desire for the organization to “show more commitment” to patient engagement. Addressing these barriers resulted in four lesson learned: (1) embed patient engagement into current improvement activities, (2) designate a neutral point person (or group) to navigate organizational complexities, (3) commit resources to support patient engagement activities; and (4) plan for sustained team-patient interactions.

1. Embed Patient Engagement into Current Improvement Activities

Patient engagement was built into the microsystem program curriculum. Making this a required component of the curriculum ensured that these activities became “standard procedure” rather than an optional endeavor. Encouraging teams to at least engage patients at the level of “Discuss” (Level 3) in our model increased both the degree and the intensity of meaningful patient engagement. For example, after teams realized that patients offered valuable insights, they were motivated to inquire into patients’ opinions about their QI goals before moving too far along with future efforts. In the words of one team physician, “the buy in came along real quickly ... We wondered if it was going to be hard to do, and it was, ‘no, this is really great.’”

2. Designate a Neutral Point Person (or Group) to Navigate Organizational Complexities

Having a “point” person (from the Center for Patient Partnerships) to interface between patients, teams, and operational leaders allowed for all parties to be involved through an intermediary. This served to deflect internal politics and sidestep bureaucratic roadblocks in our organization. For example, there was a lack of an existing policy regarding requirements for engaged patients, such as those that existed for hospital volunteers. External consultants met with key organizational stakeholders in Patient Relations, Volunteer Services, and Legal departments and discussed relevant concerns, drafted language, and then sought approval of a new policy applicable to “Engaged Patients.” Participants in the initiative perceived that consultants were able to reach a satisfactory resolution on complex, cross-organizational policy, and legal considerations faster than they believed would have been possible absent external involvement. This does not preclude the possibility of primarily using internal resources to guide a similar effort, but clearly an organization must then ensure that there is solid administrative support for the kind of flexibility, innovation, and coordination that the Center for Patient Partnerships provided in our initiative.

3. Commit Resources to Support Patient Engagement Activities

Including patients in care team meetings was challenging, as it was difficult to identify a location and time that was convenient for both patients and care teams. For teams, nondirect patient care time is scarce. It is important to think through how staff will meet, when, and where so that overtime is not required nor unpaid staff time compromised. For patients, engagement may require support for transportation and securing necessary paperwork. The organization commitment to coaching resources was also important. Coaches not only supported teams by transferring improvement and patient engagement skills but also brought the discipline to continued meeting and progress. Multiple team members independently commented that the coach “keeps us on track.” In addition, coaches, with their specialized knowledge and facilitative skills, were critical for teams in identifying opportunities and methods for engaging patients that matched a team's readiness.

The organization dedicated funds to clinic-level patient engagement activities, including transportation, food, and meeting supplies. However, we found that very little financial support was actually required to successfully engage patients in clinic improvement activities. Patients were eager to participate and required minimal financial support. Staff, however, perceived the dedication of funds as a sign of the organization's true valuation of patient engagement activities; the gesture proved significant to support staff morale and commitment to attempt patient engagement.

4. Plan for Sustained Team-Patient Interactions

We found that patients were much more willing to share critical opinions as relationships matured. This required repeated interactions over several meetings with the patients and the team. Anecdotally, patients engaged at higher levels began to identify themselves publicly as members of the team.

Discussion

In this article, we describe our experience in incorporating patient engagement into an ambitious primary care redesign initiative involving 47 academic and community primary care clinics located in the state of Wisconsin. National priorities driven by emerging redesign models4,5,7 and public policy8 have brought the need to involve patients in primary care quality improvement to the forefront. We also identify key organizational components critical for fostering a culture of patient engagement and describe the lessons we learned during this process. Our experience can serve as an example for others interested in engaging patients with teams working to redesign primary care. This information adds a practical, frontline care team component to prior discussions that have primarily focused on achieving patient-centered care through engaging patients via boards and committees.10–12

Our experience begins to address two questions important for increasing patient engagement in primary care: How does patient engagement become a prominent and visible feature of a transformed health care organization? and What approaches increase the likelihood that patient engagement becomes a cultural norm in an organization? To offer insight into factors critical to drive culture change, we have focused on organizational issues rather than operational or tactical issues; the on-the-ground details will be the focus of a subsequent publication targeted to program implementers.25

Our work in engaging patients in primary care redesign has been an important complement to the organization's efforts directed to creating a patient- and family-centered culture. Since 2006, the number of UW Health patient and family advisors has grown from 20 to more than 140. Improvement coaches who supported microsystem teams’ patient engagement activities have transferred these skills to other teams, including those involved in inpatient improvement initiatives. Patient engagement has been visible through the organization as patients participate at collaborative learning sessions, present with their teams at improvement celebrations, and have volunteered to be videotaped as they describe their experiences working with frontline care teams. In addition, the organization sends new groups of leaders to the Institute for Patient and Family Centered Care on an annual basis.

Employing simultaneous and complementary “bottom-up” and “top-down” strategies was critical to our organization's ability to incorporate patient engagement as a core component of practice redesign. The bottom-up approach—which empowers frontline teams to involve patients as partners in redesign—provides visibility into the valuable insights, perspectives, and contributions of patients. This creates champions and supporters within care teams who serve to influence others and drive a culture of patient engagement up and through the organization. This bottom-up approach complements the top-down strategy driven by senior organizational leaders. Leaders set the conditions that smooth the path for the inclusion of patient engagement as a key organizational attribute. Leaders communicate their vision of a transformed organization, set expectations, and commit resources, including engaging experts. Although not explicitly targeted in our program, ideally, middle management (for example, clinic leaders) would have a role and expectations clarified by specific training. Together, these bottom-up and top-down strategies strengthen the organization's capacity to engage patients in redesign and accelerate a culture change that embraces patients as partners. However, future efforts should also incorporate middle management.

Conclusion

Current national health care policy and local market pressures are compelling partnering with patients in efforts to improve the value of the health care delivery system. Health care delivery systems across the country are responding to national requirements to demonstrate patient engagement and measure the patient experience, and many systems are engaged in efforts to redesign primary care. We found that patients provided unique and essential contributions to the redesign process. We also found that simultaneous top-down and bottom-up strategies were necessary to achieve increased patient engagement. Our experience will be useful for those seeking to introduce or strengthen the patient role in designing delivery system improvements in a variety of organizational settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sue Ertl, Pratik Prajapati, and Lauren Fiedler for their contributions to program design and implementation. They also thank Zaher Karp and Mindy Smith for their editorial assistance. This work would not have been possible without the participation of the microsystem teams and the authors’ patient partners.

The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant 9U54TR000021. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States government. In addition, Nancy Pandhi is supported by a National Institute on Aging Mentored Clinical Scientist Research Career Development Award, grant number l K08 AG029527. This project was also supported by the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center (UWCCC) Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute, grant number P30 CA014520. Additional support was provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health from the Wisconsin Partnership Program.

Contributor Information

William Caplan, Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, and Member, Primary care Academics Transforming Healthcare (PATH) Collaborative, UW Health..

Sarah Davis, University of Wisconsin Law School, Madison; Associate Director, Center for Patient Partnerships; and Member, PATH Collaborative..

Sally Kraft, High Value Healthcare Collaborative, Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Hanover, New Hampshire; Vice President, Population Health, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire; and Member, PATH Collaborative..

Stephanie Berkson, University of Wisconsin Medical Foundation, and Member, PATH Collaborative..

Martha Gaines, University of Wisconsin Law School, and Director, Center for Patient Partnerships, University of Wisconsin..

William Schwab, Department of Family Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health..

Nancy Pandhi, Department of Family Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, and Lead, PATH Collaborative. Please address correspondence to Nancy Pandhi, nancy.pandhi@fammed.wisc.edu..

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. N Engl J Med. Jun 25. 2009;360(26):2693–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berenson RA, et al. A house is not a home: keeping patients at the center of practice redesign. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(5):1219–1230. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nutting PA, et al. Initial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):254–260. doi: 10.1370/afm.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner EH, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Standards for the Patient Centered Medical Home. NCQA; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [Oct 14, 2014];42 CFR Part 425. Medicare Program; Medicare Shared Savings Program: Accountable Care Organizations; Final Rule. 2011 Nov 2; http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-11-02/pdf/2011-27461.pdf.

- 9.Scholle SH, et al. Engaging Patients and Families in the Medical Home. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Jun, 2010. [Oct 20, 2014]. http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/Engaging%20Patients%20and%20Families%20in%20the%20Medical%20Home.pdf. (Prepared by Mathematica Policy Research under Contract No. HHSA290200900019ITO2.)

- 10.Luxford K, Safran DG, Delbanco T. Promoting patient-centered care: a qualitative study of facilitators and barriers in healthcare organizations with a reputation for improving the patient experience. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(5):510–515. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaller D. Patient-Centered Care: What Does It Take? Commonwealth Fund; New York City: Oct, 2007. [Oct 20, 2014]. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/usr_doc/Shaller_patient-centeredcarewhatdoesittake_1067.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leonhardt KK, Bonin D, Pagel P. Guide for Developing a Community-Based Patient Safety Advisory Council. Accessed Oct. Vol. 20. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Apr, 2008. p. 2014. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/advisorycouncil/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han E, et al. Survey shows that fewer than a third of patient-centered medical home practices engage patients in quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):368–375. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis S, Gaines M. Patient Engagement Toolkit. Engage 2 Transform and the Center for Patient Partnerships at the University of Wisconsin, Madison; Madison, WI: 2014. http://hipxchange.org/PatientEngagement. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson EC, et al. Microsystems in health care: Part 1. Learning from high-performing front-line clinical units. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28(9):472–493. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(02)28051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care Frequently Asked Questions. [Oct 22, 2014];What is patient- and family-centered health care? http://www.ipfcc.org/faq.html.

- 17.University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Authority . Primary Care Redesign Vision. Wisconsin; Madison: 2009. UW Health Strategic Priorities. (unpublished document) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berwick DM. A user's manual for the IOM's 'Quality Chasm' report. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21(3):80–90. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health Canada, Corporate Consultation Secretariat, Health Policy and Communications Branch. [Oct 14, 2014];Health Canada Policy Toolkit for Public Involvement in Decision Making. 2000 http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/pubs/_public-consult/2000decision/index-eng.php.

- 21.Carman KL, et al. Patient and family engagement: A framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):223–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation . Engaging Patients in Improving Ambulatory Care: A Compendium of Tools from Maine, Oregon, and Humboldt County. California: Mar, 2013. [Oct 23, 2014]. http://www.rwjf.org/en/research-publications/find-rwjf-research/2013/03/engaging-patients-in-improving-ambulatory-care.html. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delbecq A, Van de Ven A, Gustafson D. Group Techniques for Program Planning: A Guide to Nominal Group and Delphi Processes. Scott, Foresman & Company; Glenview, IL: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [Oct 14, 2014];Health Information Privacy. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/

- 25.Davis S, et al. Engaging patients in team-based practice redesign: Critical reflections on program design. Wisconsin; Madison: Oct, 2014. (unpublished manuscript) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]