Significance

How neuronal circuits maintain stable activity despite continuous environmental changes is one of the most intriguing questions in neuroscience. Previous studies proposed that deficits in homeostatic control systems may underlie common neurological symptoms in a variety of brain disorders. However, the key regulatory molecules that control homeostasis of central neural circuits remain obscure. We show here that basal activity of GABAB receptors is required for firing rate homeostasis in hippocampal networks. We identified the principal mechanisms by which GABAB receptors control homeostatic augmentation of synaptic strength to chronic neuronal silencing. We propose that deficits in GABAB receptor signaling, associated with epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, may lead to aberrant brain activity by erasing homeostatic plasticity.

Keywords: homeostatic plasticity, GABAB receptor, synaptic vesicle release, syntaxin-1, FRET

Abstract

Stabilization of neuronal activity by homeostatic control systems is fundamental for proper functioning of neural circuits. Failure in neuronal homeostasis has been hypothesized to underlie common pathophysiological mechanisms in a variety of brain disorders. However, the key molecules regulating homeostasis in central mammalian neural circuits remain obscure. Here, we show that selective inactivation of GABAB, but not GABAA, receptors impairs firing rate homeostasis by disrupting synaptic homeostatic plasticity in hippocampal networks. Pharmacological GABAB receptor (GABABR) blockade or genetic deletion of the GB1a receptor subunit disrupts homeostatic regulation of synaptic vesicle release. GABABRs mediate adaptive presynaptic enhancement to neuronal inactivity by two principle mechanisms: First, neuronal silencing promotes syntaxin-1 switch from a closed to an open conformation to accelerate soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex assembly, and second, it boosts spike-evoked presynaptic calcium flux. In both cases, neuronal inactivity removes tonic block imposed by the presynaptic, GB1a-containing receptors on syntaxin-1 opening and calcium entry to enhance probability of vesicle fusion. We identified the GB1a intracellular domain essential for the presynaptic homeostatic response by tuning intermolecular interactions among the receptor, syntaxin-1, and the CaV2.2 channel. The presynaptic adaptations were accompanied by scaling of excitatory quantal amplitude via the postsynaptic, GB1b-containing receptors. Thus, GABABRs sense chronic perturbations in GABA levels and transduce it to homeostatic changes in synaptic strength. Our results reveal a novel role for GABABR as a key regulator of population firing stability and propose that disruption of homeostatic synaptic plasticity may underlie seizure's persistence in the absence of functional GABABRs.

Neural circuits achieve an ongoing balance between plasticity and stability to enable adaptations to constantly changing environments while maintaining neuronal activity within a stable regime. Hebbian-like plasticity, reflected by persistent changes in synaptic and intrinsic properties, is crucial for refinement of neural circuits and information storage; however, alone it is unlikely to account for the stable functioning of neural networks (1). In the last 2 decades, major progress has been made toward understanding the homeostatic negative feedback systems underlying restoration of a baseline neuronal function after prolonged activity perturbations (2–4). Homeostatic processes may counteract the instability by adjusting intrinsic neuronal excitability, inhibition-to-excitation balance, and synaptic strength via postsynaptic or presynaptic modifications (5, 6) through a profound molecular reorganization of synaptic proteins (7, 8). These stabilizing mechanisms have been collectively termed homeostatic plasticity. Homeostatic mechanisms enable invariant firing rates and patterns of neural networks composed from intrinsically unstable activity patterns of individual neurons (9).

However, nervous systems are not always capable of maintaining constant output. Although some mutations, genetic knockouts, or pharmacologic perturbations induce a compensatory response that restores network firing properties around a predefined “set point” (10), the others remain uncompensated, or their compensation leads to pathological function (11). The inability of neural networks to compensate for a perturbation may result in epilepsy and various types of psychiatric disorders (12). Therefore, determining under which conditions activity-dependent regulation fails to compensate for a perturbation and identifying the key regulatory molecules of neuronal homeostasis is critical for understanding the function and malfunction of central neural circuits.

In this work, we explored the mechanisms underlying the failure in stabilizing hippocampal network activity by combining long-term extracellular spike recordings by multielectrode arrays (MEAs), intracellular patch-clamp recordings of synaptic responses, imaging of synaptic vesicle exocytosis, and calcium dynamics, together with FRET-based analysis of intermolecular interactions at individual synapses. Our results demonstrate that metabotropic, G protein-coupled receptors for GABA, GABABRs, are essential for firing rate homeostasis in hippocampal networks. We explored the mechanisms by which GABABRs gate homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Our study raises the possibility that persistence of epileptic seizures in GABABR-deficient mice (13–15) is directly linked to impairments in a homeostatic control system.

Results

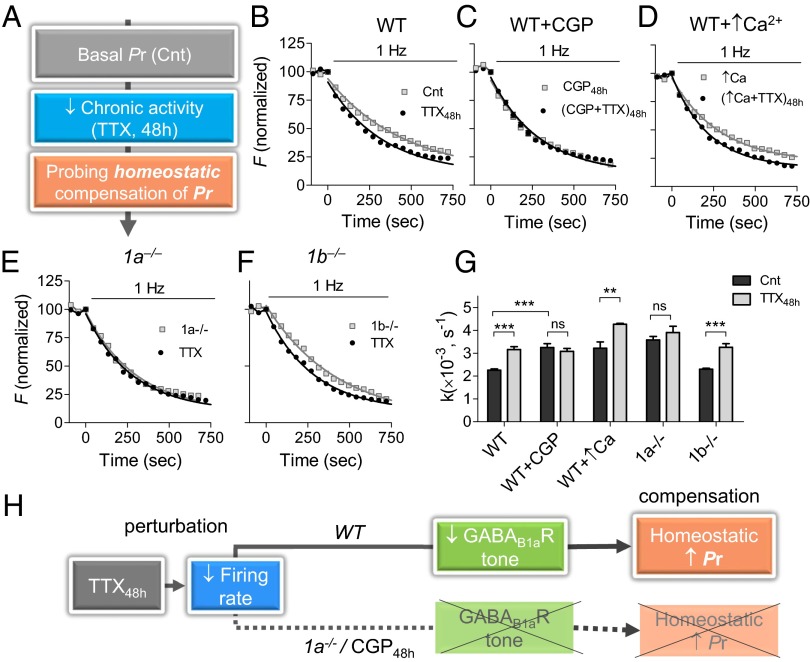

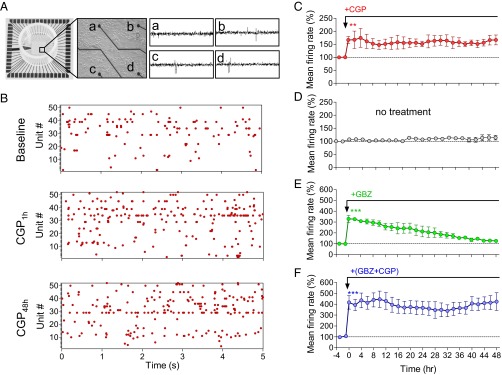

GABABR Blockade Disrupts Firing Rate Homeostasis.

Mice lacking functional GABABRs because of GB1 or GB2 subunit deletion display continuous spontaneous seizure activity (13–16). These findings are quite counterintuitive in light of a wide range of G protein-coupled receptors that mediate synaptic inhibition and might compensate for GABABR loss of function. Therefore, we hypothesized that functional GABABRs may play an essential role in neuronal homeostasis. To test this hypothesis, we examined homeostasis of mean firing rate of a neuronal population after chronic blockade of GABABRs. To chronically monitor neuronal activity in stable neural populations, we grew hippocampal cultures on MEAs for ∼3 wk. Each MEA contains 59 recording electrodes, with each electrode capable of recording the activity of several adjacent neurons (Fig. 1A). Spikes were detected and analyzed using principal component analysis to obtain well-separated single units that were consistent throughout at least 2 d of recording (SI Appendix, Methods). To assess how chronic inhibition of the basal GABABR activity affects mean firing rate of neural network, we measured spiking activity during a baseline recording period and for 2 d after application of CGP54626 (CGP), a selective GABABR antagonist. Fig. 1B illustrates raster plots during periods of baseline, 1 h, and 48 h after 1 μM CGP application in a single experiment. Indeed, CGP causes an acute increase of 67 ± 13% in the mean firing rate (Fig. 1C), confirming proconvulsive properties of GABABR antagonists in vivo (17). However, to our surprise, mean firing rate was not normalized during 2 d in the constant presence of CGP. After 2 d, firing rate remained 67 ± 18% higher in the presence of GABABR antagonist (P < 0.01; Fig. 1C). Notably, under control conditions, network spike rates were stable during the 2 d of recording (no treatment, P > 0.2 between 1 h and 48 h; Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

GABABR blockade disrupts firing rate homeostasis in hippocampal networks. (A, Left) Image of MEA dish. (Middle) Image of dissociated hippocampal culture plated on MEA. Black circles at the end of the black lines are the recording electrodes. (Right) Representative traces of recording from four MEA channels (a, b, c, and d). (B) Representative raster plot of MEA recording before and 1 and 48 h after application of the GABABR antagonist CGP (1 μM). (C–F) Mean firing rate of hippocampal neuronal cultures incubated with CGP (n = 4; C), no treatment (Cnt, n = 6; D), gabazine (GBZ, 30 μM, n = 4; E), and CGP+GBZ (n = 4; F) during 2 d of MEA recordings.

To confirm that the lack of firing rate homeostasis is specific to the GABABR blockade, we examined how chronic blockade of GABAARs affects the population firing rate in hippocampal networks. Application of GABAAR antagonist gabazine (30 µM) caused a fast and pronounced increase in the population firing rate to 330 ± 32%, which gradually declined over the course of 2 d in the presence of gabazine (Fig. 1E), despite the constant presence of the antagonist. Washout of gabazine after 2 d caused a significant decrease in firing rate, indicating sustained activity of both gabazine and the GABAARs (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Moreover, a GABABR agonist, baclofen, triggered a pronounced block of firing rate that was precisely restored to the baseline level after a period of 2 d (9). The observed compensatory responses to increase in spiking activity by GABAAR antagonist or decrease in spiking activity by GABABR agonist confirm the idea that homeostatic mechanisms maintain stable circuit function by keeping neuronal firing rate around a “set point” (10, 18).

Given a 3.4-fold difference in the magnitude of the initial firing rate increase produced by GABAAR versus GABABR blockade, it is plausible that the lack of firing rate renormalization in the presence of CGP was a result of its relatively weak effect on firing rate. If this is the case, concurrent blockade of GABAARs and GABABRs would result in a reversal of firing rate, as in the presence of the GABAAR blocker alone. However, coapplication of gabazine and CGP triggered an initial increase in firing rate by 416 ± 61% that remained at 415 ± 63% for 2 d in the presence of the GABAR blockers (P < 0.001; Fig. 1F), suggesting selective GABABR blockade truly disrupts firing rate renormalization. Altogether, these results demonstrate that ongoing GABABR activity is required for firing rate homeostasis in hippocampal networks.

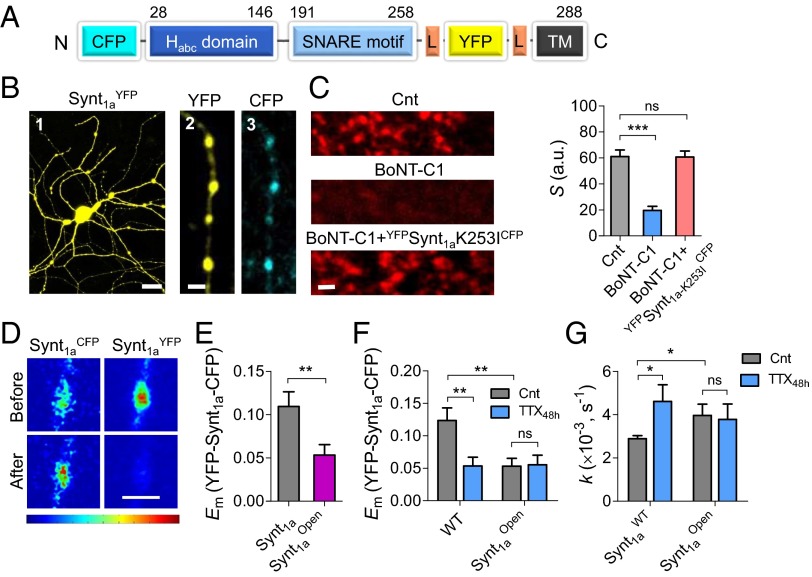

GB1a-Containing GABABRs Mediate Homeostatic Increase in Evoked Vesicle Release.

What are the mechanisms underlying disruption of firing rate homeostasis by GABABR blockade? To address this question, we assessed the dependency of synaptic homeostatic responses that normally contribute to firing rate homeostasis on the GABABR function during activity changes. As a perturbation, we applied tetrodotoxin for 48 h (TTX48h) to silence spiking activity, a classical paradigm in homeostasis research. First, we asked whether active GABABRs are required for inactivity-induced increase in spike-evoked vesicle exocytosis estimated by the FM1-43 method (19). To this end, the total pool of recycling vesicles was stained by maximal stimulation (600 stimuli at 10 Hz) and subsequently destained by 1 Hz stimulation (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). TTX48h induced a 1.4-fold increase in the destaining rate constant (measured as 1/τdecay, whereas τdecay is an exponential time course) and, thus, vesicle exocytosis (P < 0.001; Fig. 2 B and G). However, the adaptive enhancement of release probability (Pr) to inactivity was abolished when neurons were treated with TTX in the presence of CGP over the course of 48 h [(TTX + CGP)48h; P > 0.4; Fig. 2 C and G]. Importantly, CGP application acutely increased FM destaining rate (P < 0.01; SI Appendix, Fig. S2B), which remained elevated for 48 h in the presence of CGP (CGP48h; P < 0.01; Fig. 2 C and G), indicating that the expected compensatory reduction in Pr was impaired under the GABABR blockade. Acute application of CGP after TTX48h treatment during FM destaining did not alter adaptive increase in vesicle exocytosis (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). It is noteworthy that Pr was not saturated under GABABR blockade, as presynaptic homeostatic compensation by TTX48h was normally expressed in high-Pr boutons under elevated extracellular Ca2+ levels (Fig. 2 D and G and SI Appendix, Fig. S2D). Moreover, GABAAR blockade by gabazine for 48 h induced an adaptive reduction in Pr that was prevented by CGP coapplication (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Thus, the failure in the homeostatic mechanisms is not associated with modulation of basal Pr. Taken together, these results indicate that basal GABABR activity is necessary to achieve a compensatory increase in spike-evoked synaptic vesicle exocytosis in hippocampal synapses.

Fig. 2.

Presynaptic homeostatic response is impaired by GABABR blockade or GB1a deletion. (A) Experimental protocol for determining changes in synaptic vesicle exocytosis after prolonged inactivity by TTX48h (0.5 µM, 48 h). (B–F) Representative FM destaining rate curves of 50 synapses incubated with/without TTX48h in WT neurons (B), WT neurons treated by CGP48h (1 µM CGP for 48 h; C), WT neurons grown in increased (2 mM) Ca2+ concentration (D), 1a−/− neurons (E), and 1b−/− neurons (F). (G) Effect of TTX48h on average destaining rate constants in WT neurons (n = 687–701), WT neurons incubated with CGP48h (n = 593–748), WT neurons in presence of high Ca2+ (n = 278–331), 1a−/− neurons (n = 313–327), and 1b−/− neurons (n = 303–313). (H) Schematic illustration of TTX48h-induced Pr homeostatic regulation by neuronal inactivity via GABAB1aRs.

Which isoform of the GABABRs mediates homeostatic increase in evoked vesicle release? GABABRs are obligatory heterodimers, requiring two homologous subunits, GB1 and GB2, for functional expression (20). In hippocampal synapses, the GB1a isoform is predominantly expressed at glutamatergic presynaptic boutons, whereas GB1b is predominantly expressed at spines (21). Thus, we examined whether the presynaptic homeostatic response is disrupted in 1a−/− boutons lacking the GB1a receptor subunit (21). The 1a−/− boutons did not display a presynaptic response to activity blockade (Fig. 2 E and G). The deficits in presynaptic homeostatic plasticity were specific for the GB1a isoform, as 1b−/− boutons displayed a typical adaption to prolonged synaptic inactivity (Fig. 2 F and G). Notably, acute application of CGP increased evoked synaptic vesicle release in the wild-type and 1b−/−, but not 1a−/−, boutons (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), confirming that the GB1a-containing receptors mediate inhibition of Pr by local GABA levels. Although our previous data demonstrated a correlation between inactivity-induced reduction in the GB1a receptor activity and increase in Pr (22), our current results suggest that the basal GB1a receptor activity is required for homeostatic Pr regulation (Fig. 2H).

In contrast to inactivity-induced regulation of spike-evoked vesicle exocytosis, neither acute (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) nor chronic (SI Appendix, Fig. S6) application of CGP affected miniature excitatory postsynaptic current (mEPSC) frequency. Moreover, TTX48h alone or in the presence of CGP48h did not significantly change mEPSC frequency (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). It is worth mentioning that TTX48h reduced short-term synaptic facilitation during spike bursts measured by double-patch recordings (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), indicating an increase in Pr (23). Thus, the difference between spike-evoked and spontaneous vesicle release regulation observed under our experimental conditions reflects differential regulation of exocytosis during spontaneous and evoked synaptic activity (24). Although GABABR blockade did not affect regulation of mEPSC frequency, it impaired inactivity-induced increase in mEPSC amplitude, suggesting the postsynaptic GABABRs are involved in this regulation. Indeed, the effect of TTX48h was absent in 1b−/− neurons (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), suggesting the GB1b-containg postsynaptic GABABRs play an important role in synaptic scaling.

Inactivity Promotes Syntaxin-1 Conformational Switch.

What are the molecular mechanisms underlying the homeostatic increase in Pr by presynaptic GABABRs? SNARE-complex assembly is initiated by a syntaxin-1 (Synt1) switch from its closed conformation (in which the N-terminal Habc domain of Synt1 folds back onto its SNARE domain) into an open conformation (in which the SNARE domain becomes unmasked for SNARE-complex formation) (25). Rendering Synt1 constitutively open induces an increase in Pr by enhancing SNARE-complex assembly per vesicle (26). However, activity-dependent mechanisms regulating Synt1 conformational switch are not fully understood.

To assess whether chronic inactivity promotes Synt1 opening, we used a recently developed intramolecular Synt1a FRET probe (CFP-Synt1a-YFP) that reports the closed-to-open transition as a decrease in FRET efficiency (27). The Synt1a sensor contains CFP fluorophore inserted at the N terminus and YFP inserted after the SNARE motif (Fig. 3A) and is well expressed in processes of hippocampal neurons (Fig. 3B). The engineered Synt1a FRET reporter has been shown to assemble into endogenous SNARE complexes and was able to reconstitute dense-core vesicle exocytosis in PC12 cells (27). Furthermore, we show that neurons transfected with the light chain of BoNT-C1 are not capable of synaptic vesicle recycling, even during strong stimulation (600 pulses at 20 Hz; Fig. 3C). However, coexpression of BoNT-C1, together with BoNT-C1-insensitive CFP-Synt1aK253I-YFP mutant reporter, restores synaptic vesicle recycling to the level observed in wild-type neurons (Fig. 3C). These results strongly suggest the CFP-Synt1a-YFP FRET reporter is functional, supporting synaptic vesicle exocytosis in hippocampal neurons.

Fig. 3.

Homeostatic mechanisms promote closed-to-open Synt1a conformational switch by neuronal inactivity. (A) Schematic illustration of Synt1a FRET construct (27). (B) Representative confocal image of a hippocampal neuron transfected with CFP-Synt1a-YFP and zoom-in image of an axon. (C, Left) Synaptic vesicle recycling is blocked in neurons expressing BoNT-C1 light chain but is rescued by CFP-Synt1a-K253I-YFP FRET probe. FM4-64 staining during 20-Hz stimulation (600 APs). (Right) Quantification of total presynaptic strength (S) in neurons expressing (1) CFP only (Cnt, n = 8) (2), BoNT-C1 (n = 12), and (3) BoNT-C1 + CFP-Synt1a-K253I-YFP FRET probe (n = 9). (D) Pseudocolor-coded fluorescent images of CFP-Synt1a-YFP protein expressing bouton before and after YFP photobleaching. (E) Synt1aOpen reduces Em (n = 30–38). (F) Summary of the TTX48h effect in neurons expressing wild-type Synt1a probe (n = 23–34) and Synt1aOpen (n = 38–25). (G) Average destaining rate constants in Synt1aWT (n = 284), Synt1aWT treated by TTX48h (n = 181), Synt1aOpen (n = 270), and Synt1aOpen treated by TTX48h (n = 192). [Scale bars, 20 µm (B, 1) and 2 µm (B, 2 and 3, and D)].

To monitor Synt1a conformational changes, we measured the steady-state FRET efficiency (Em), using the acceptor photobleaching method at presynaptic boutons expressing CFP-Synt1a-YFP (Fig. 3B, 2 and 3). High-magnification confocal images show an increase in CFP fluorescence after YFP photobleaching (Fig. 3D), indicating dequenching of the donor and the presence of FRET. On average, CFP-Synt1a-YFP FRET efficiency across hippocampal boutons was 0.12 ± 0.02 (Fig. 3E). To validate that the probe reports closed-to-open transition as a decrease in FRET efficiency, we used the Synt1aOpen FRET probe with L165E/L166E mutations, rendering Synt1 in a constitutively open conformation (25). Indeed, Synt1aOpen displayed 56% lower FRET efficiency in comparison with the wild-type Synt1a probe (0.053 ± 0.01; P < 0.01; Fig. 3E).

Next, we asked whether Synt1a conformation is homeostatically regulated by chronic neuronal inactivity to promote Pr augmentation. Indeed, TTX48h induced a reduction in Synt1a FRET to 0.05 ± 0.01 (P < 0.01; Fig. 3F). Notably, the reduction magnitude by TTX48h was similar to that exhibited by Synt1aOpen and was occluded by Synt1aOpen. At the functional level, Synt1aOpen increased the rate of vesicle exocytosis (P < 0.05; Fig. 3G), supporting results of earlier studies (26, 28). Most important, Synt1aOpen occluded the effect of TTX48h on Pr (P > 0.7; Fig. 3G), suggesting a functional importance of Synt1a opening in compensatory Pr augmentation.

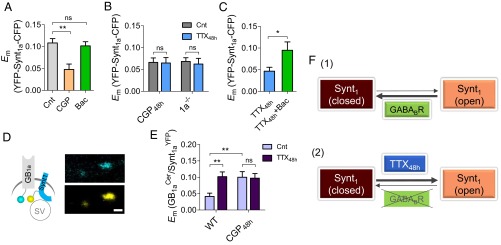

Removal of GABABR Block Mediates Inactivity-Induced Syntaxin-1 Opening.

To examine whether GABABR tone is required for inactivity-induced Synt1a opening, we first asked whether Synt1a conformation is regulated by basal GABABR activity. Acute application of GABABR antagonist CGP reduced mean FRET level to 0.048 ± 0.01 (P < 0.01; Fig. 4A). Application of GABABR agonist baclofen (10 μM) did not affect FRET (P > 0.05; Fig. 4A), indicating that basal GABA levels are sufficient to stabilize a closed Synt1a conformation. Next, we asked whether GABABR blockade interferes with TTX48h-induced Synt1a opening. CGP48h caused a reduction in Synt1a FRET (P < 0.01; Fig. 4B) and occluded the effect of TTX48h on Syn1a conformational change (Fig. 4B). The effect of CGP48h was mimicked by deletion of the GB1a receptor subunit: Synt1a FRET was twofold lower in 1a−/− boutons and insensitive to chronic reduction in spiking activity by TTX48h (Fig. 4B). Importantly, acute application of baclofen restored Synt1a FRET in TTX48h-treated neurons (Fig. 4C), suggesting prolonged silencing may promote Synt1a opening by reducing the extracellular GABA levels (22).

Fig. 4.

Neuronal inactivity promotes Synt1 opening by removal of GABABR-mediated block. (A) Acute application of CGP reduced CFP-Synt1a-YFP Em (n = 38), whereas 10 μM baclofen did not affect it (n = 88) in WT neurons. (B) Summary of the TTX48h effect on CFP-Synt1a-YFP Em in the presence of CGP48h in WT (n = 42–45) and in 1a−/− (n = 40–80) neurons. (C) Baclofen (10 µM) rescued TTX48h-induced FRET reduction (n = 25–40). (D) Representative confocal images of boutons cotransfected with GB1aCer and Synt1aYFP. (Scale bar, 1 µm.) (E) Effect of TTX48h on GB1aCer/Synt1aYFP Em (n = 48–57). CGP48h increases GB1aCer/Synt1aYFP Em and abolishes TTX48h-induced Em changes (n = 41–69). (F) Schematic illustration of Synt1 conformational switch regulation by neuronal inactivity via GABABRs.

Having established the necessity for GB1a-containing GABABRs in the homeostatic conformational change of Synt1a, we explored a possibility of Synt1a and GB1a interactions. To quantify activity-dependent changes in GB1a–Synt1a interactions at individual presynaptic sites, we used the FRET approach. To preserve the functionality of the Synt1a FRET reporter, we replaced CFP by its nonfluorescent mutant CFP-W66A, and a Cerulean (Cer)-tagged GB1a subunit at the C terminus (GB1aCer) was used as a donor (Fig. 4D). Basal GB1aCer/Synt1aYFP FRET efficiency was 0.04 ± 0.01 and underwent a 2.4-fold increase by TTX48h (P < 0.01; Fig. 4E). Notably, blockade of GABABRs produced a similar effect (P < 0.01; Fig. 4E), indicating that GB1a/Synt1a interactions are regulated by basal GABA. Moreover, CGP48h occluded TTX48h-induced GB1aCer/Synt1aYFP FRET changes (P = 0.9; Fig. 4E). To determine the existence of endogenous protein complexes containing Synt1 and GABABRs, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments with solubilized mouse brain membranes. Anti-Synt1 antibodies coprecipitated a significant amount of GB1 proteins together with Synt1 from WT, but not from full GB1-KO mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Taken together, these results indicate that Synt1a conformational change constitutes a critical step in presynaptic homeostatic response, that basal GABABR activity maintains Synt1a in a closed conformation (Fig. 4F, 1), and that prolonged inactivity removes a GABABR-imposed clamping of a closed Synt1a conformation, allowing Synt1a shift toward its open conformation (Fig. 4F, 2).

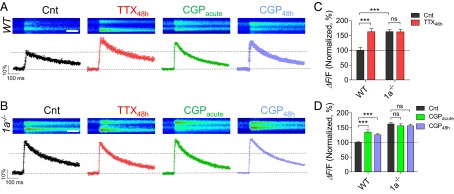

GB1a Is Required for Homeostatic Increase in Presynaptic Calcium Flux.

Next, we examined whether the GB1a receptor subunit controls homeostatic regulation of presynaptic Ca2+ transients (29), in addition to regulating Synt1 conformational switch, to adapt Pr to chronic activity perturbations. Thus, we measured presynaptic Ca2+ transients evoked by 0.1-Hz stimulation, using high-affinity fluorescent calcium indicator Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 AM (Fig. 5A) at functional boutons identified by the FM4-64 marker. Although the size of action-potential dependent fluorescence transients (ΔF/F) varied between different boutons, presynaptic Ca2+ flux was significantly larger in TTX48h-treated WT neurons (P < 0.0001; Fig. 5 A and C). Importantly, presynaptic Ca2+ flux was higher in boutons of 1a−/− neurons (P < 0.0001; Fig. 5 B and C), occluding the effect of TTX48h on further potentiation of calcium transients. It is noteworthy that Ca2+ transients were not saturated by single action potential in 1a−/− boutons (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Furthermore, acute application of CGP increased presynaptic Ca2+ flux that remained stable over the course of 2 d in the presence of CGP in WT (P < 0.001; Fig. 5 A and D), but not in 1a−/− (P > 0.4; Fig. 5 B and D), neurons. This lack of compensation at the level of Ca2+ flux was specific for the GABABR deficit, as GABAAR blockade by gabazine has been previously shown to trigger an adaptive reduction in presynaptic Ca2+ transients (29). These results indicate that GB1a-containing GABABRs normally inhibit presynaptic Ca2+ flux evoked by single action potential and that removal of the GABABR-mediated block is essential for homeostatic potentiation of Ca2+ flux by chronic inactivity.

Fig. 5.

Homeostatic increase in presynaptic calcium flux is impaired by GB1a deletion. (A and B) TTX48h increased spike-dependent presynaptic Ca2+ entry in boutons of WT, but not in 1a−/− neurons. (Top) Representative images of Ca2+ transients (average of seven traces) evoked by 0.2-Hz stimulation during a 500-Hz line scan in boutons under control, or TTX48h, CGPacute, and CGP48h conditions in WT (A) and 1a−/− (B) neurons. (Scale bar, 100 ms.) (Bottom) Averaged Ca2+ transients, quantified as ΔF/F, in control (n = 20), TTX48h (n = 15), CGPacute (n = 29), and CGP48h (n = 37) conditions in WT (A) and 1a−/− (B, n = 20, 21, 23, and 66 for Cnt, TTX48h, CGPacute, and CGP48h, respectively) neurons. (C) Summary of TTX48h effect (percentage of control) on Ca2+ transients in boutons of WT versus 1a−/− neurons (the same data as in A and B). Note that Ca2+ transients were higher in 1a−/− boutons than in WT ones. (D) Summary of CGPacute and CGP48h effects (percentage of control) on Ca2+ transients in WT versus 1a−/− boutons (the same data as in A and B).

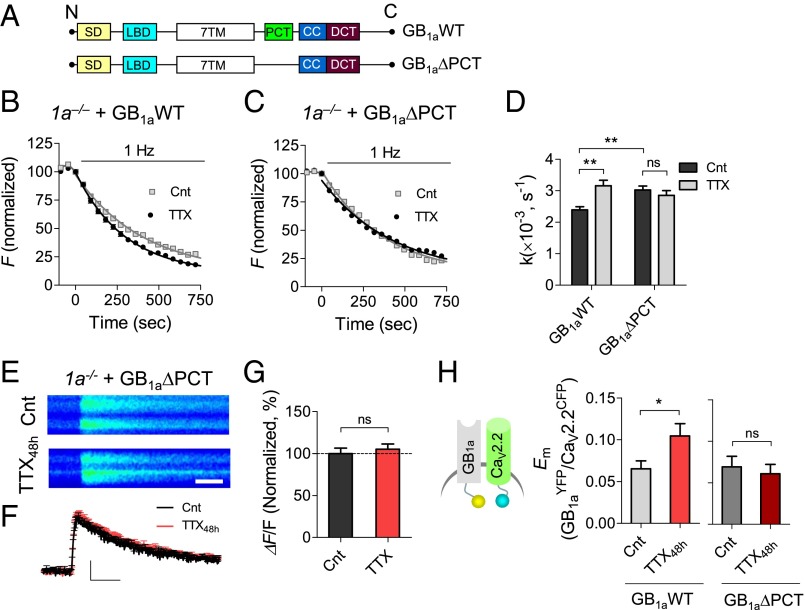

GB1aPCT Mediates Presynaptic Homeostatic Response.

Next, we searched for the molecular domain in the GB1a protein that mediates the presynaptic homeostatic response. In our previous work, we identified the proximal C-terminal domain of the GB1a protein (R857-S877; GB1aPCT; Fig. 6A) as essential for the compartmentalization of the presynaptic signaling complex of GABABRs, Gβγ G protein subunits, and CaV2.2 channels in hippocampal boutons (30). Interestingly, deletion of GB1aPCT domain specifically impaired CaV2.2/Gβγ interaction and function, leaving Gαi/o-dependent signaling unaltered.

Fig. 6.

The GB1aPCT domain is required for presynaptic homeostatic response. (A) Schematics show GB1aWT and GB1aΔPCT constructs. 7TM, seven-transmembrane domain; CC, coiled-coiled domain; DCT, distal C-terminal domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain; PCT, proximal C-terminal domain; SD, two sushi domains. (B and C) Representative FM destaining rate curves of 50 synapses pretreated with/without TTX48h in 1a−/− neurons transfected with GB1aWT (B) or GB1aΔPCT (C). (D) Expression of GB1aWT (n = 609–642), but not of GB1aΔPCT (n = 598–721), restores presynaptic homeostatic adaptation in 1a−/− neurons. (E and F) TTX48h did not alter spike-dependent presynaptic Ca2+ entry in boutons expressing GB1aΔPCT in 1a−/− neurons. Representative images of Ca2+ transients (average of seven traces) evoked by 0.2-Hz stimulation in boutons of control and TTX48h-treated GB1aΔPCT-expressing boutons (E). Averaged Ca2+ transients in control (n = 44) and TTX48h (n = 37) conditions (F). (G) Summary of TTX48h effect on Ca2+ transients in boutons expressing GB1aΔPCT protein (the same data as in F). (H) Effect of TTX48h on GB1aYFP/CaV2.2CFP Em (n = 40–88). Deletion of PCT domain abolishes TTX48h-induced change in GB1aYFP/CaV2.2CFP Em (n = 44–55).

First, we assessed the functional role of the GB1aPCT domain in the homeostatic increase of Pr by comparing the effect of TTX48h on FM4-64 destaining rates in 1a−/− neurons transfected with GB1aWT-CFP versus GB1aΔPCT-CFP proteins. Expression of the GB1aWT-CFP protein rescued inactivity-induced potentiation of vesicle exocytosis in 1a−/− neurons (P < 0.01; Fig. 6 B and D in comparison with Fig. 2G). In contrast, TTX48h-induced presynaptic enhancement remained impaired in boutons expressing GB1aΔPCT-CFP (P > 0.8; Fig. 6 C and D). Moreover, deletion of the GB1aPCT domain abolished inactivity-induced increase in presynaptic calcium transients (P > 0.8; Fig. 6 E–G). Thus, the GB1aPCT domain is necessary for presynaptic adaptations to prolonged inactivity in hippocampal networks.

Finally, we examined whether inactivity induces conformational GABABR/CaV2.2 changes, and if so, whether the GB1aPCT domain is involved in this homeostatic regulation. We monitored FRET efficiency between the YFP-tagged GB1a receptor subunit at the C terminus and the CFP-tagged α1 subunit of the CaV2.2 channel at the N terminus (GB1aYFP/CaV2.2CFP). TTX48h induced an increase in GB1aYFP/CaV2.2CFP FRET (P < 0.05; Fig. 6H), indicating that chronic neuronal silencing alters GB1a/CaV2.2 interactions. Importantly, deletion of the GB1aPCT domain disrupted TTX48h-induced homeostatic GB1aYFP/CaV2.2CFP changes (P = 0.49; Fig. 6H). Moreover, GB1aPCT deletion occluded TTX48h-induced homeostatic GB1aCer/GB2Cit and GB1aYFP/Synt1aCFP changes (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). A physical interaction between endogenous GABABRs and CaV2.2 was revealed by coimmunoprecipitation experiments (SI Appendix, Fig. S9), confirming previous proteomic data (31). These results suggest that homeostatic mechanisms modulate GB1a/CaV2.2 and GB1a/Synt1a interactions in the GABABR presynaptic signaling complex via the GB1aPCT domain.

Discussion

The ability of neuronal circuits to stabilize their firing properties in the face of environmental or genetic changes is critical for normal neuronal functioning. Despite extensive research on a wide repertoire of possible homeostatic mechanisms, the key regulators of firing rate homeostasis in mammalian central neural circuits remain obscure. In this work, we identified the GABABR as a key homeostatic signaling molecule stabilizing mean firing rate in hippocampal networks. GABABRs enable inactivity-induced homeostatic increase in synaptic strength by three principle mechanisms: promoting synatxin-1 conformational switch to enhance SNARE-complex assembly, augmenting presynaptic Ca2+ flux to promote spike-evoked vesicle exocytosis, and increasing the quantal excitatory amplitude. Thus, GABABRs, in addition to modulation of short-term (32, 33) and long-term, Hebbian (21) synaptic plasticity, are essential for maintaining firing stability of neural circuits.

GABABRs and Synaptic Homeostatic Plasticity.

Homeostatic regulation of synaptic strength represents a basic mechanism of neuronal adaptation to constant changes in ongoing activity levels. Strong evidence exists on homeostatic augmentation of Pr and readily releasable pool size in response to prolong inactivity in hippocampal neurons (19, 22, 34–42). These homeostatic adaptations are associated with modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ flux (29) and remodeling of a large number of proteins in presynaptic cytomatrix (7). Recent studies have identified the mechanisms underlying presynaptic homeostatic signaling in Drosophila neuromuscular junction, implicating epithelial sodium leak channels (43) and endostatin (44) as homeostatic regulators of the presynaptic CaV2 channels (for review, see ref. 5). However, the critical molecules controlling presynaptic homeostasis in mammalian central synapses are not fully understood.

In this work, we show that chronic neuronal silencing induces an adaptive increase in evoked basal vesicle release through GABABRs by removing tonic inhibition of Synt1 conformational switch and of presynaptic Ca2+ flux. These results are important for several reasons. First, they reveal a crucial role for GABABRs in presynaptic homeostasis. Taking into account a wide variety of G protein-coupled receptors that mediate presynaptic inhibition, the requirement for the GABABR tone in presynaptic homeostatic response is particularly striking. Second, they demonstrate, for the first time, the role of the extracellular GABA in determining Synt1 conformation via the presynaptic GB1a-containing GABABRs. Either genetic GB1a deletion or pharmacological GABABR blockade stabilizes an open Synt1 conformation in analogy to mutations rendering Synt1 constitutively open, occluding adaptive response to neuronal silencing. Notably, addition of GABABR agonist after prolonged inactivity stabilizes a closed Synt1 conformation, suggesting reduction in local GABA levels induces an adaptive Synt1a response. Third, in addition to the well-known role of GABABRs in the presynaptic Ca2+ flux inhibition, at a rapid timescale of minutes (22, 45), our work revealed the necessity for basal GABABR activity in presynaptic adaptations of Ca2+ transients to chronic activity perturbations at extended timescales of days. Deletion of the GB1aPCT domain blocks presynaptic homeostatic plasticity by disrupting GABA-mediated conformational changes within the presynaptic GB1a/CaV2.2/Synt1 signaling complex. Thus, endogenous molecular “brakes” imposed by GABABRs on CaV2.2 channels and SNARE complex assembly are essential for presynaptic homeostasis in hippocampal neurons.

It is important to note that in the present study, chronic inactivity by TTX induced a compensatory increase in mEPSC amplitude via the postsynaptic GB1b-containing receptors without affecting mEPSC frequency. Given a pronounced effect of TTX48h on spike-evoked synaptic vesicle exocytosis, these results suggest complete blockade of spikes does not trigger compensatory changes in spontaneous vesicle release. In previous studies, mEPSC frequency was found to be immune to chronic TTX treatment in some cases (18, 41), while being up-regulated by AMPA receptor blockade (36, 41), either by suppression of neuronal excitability (38) or by increase in the GABABR-mediated inhibition (9). Thus, the induction of presynaptic homeostatic changes may require minimal spiking activity (41).

GABABR-Mediated Neuronal Homeostasis and Brain Disorders.

It is tempting to speculate that many distinct neurologic and psychiatric disorders with different etiologies share common dysfunctions in pathways related to homeostatic plasticity. However, the molecular mechanisms by which defective homeostatic signaling may lead to common disease pathophysiology remain to be determined. Only a few molecular links, such as the schizophrenia-associated gene dysbindin, have been established between homeostatic system impairments and brain dysfunctions (46). Our study demonstrates that ongoing GABABR activity is essential for population firing rate homeostasis in hippocampal networks. This may explain why aberrant neuronal activity remains uncompensated in mice lacking functional GABABRs as a result of deletion of either the GB1 (13) or GB2 (15) receptor subunit. Interestingly, 1a−/−, but not 1b−/−, mice exhibit spontaneous epileptiform activity (16), suggesting the presynaptic GB1a-containing receptors may play a more prominent role in firing rate homeostasis. Strikingly, our results show that homeostatic plasticity is impaired in synaptic networks displaying enhanced ongoing synaptic Ca2+ flux because of removal of the GABABR-mediated block. Thus, CaV2 channel gain of function may be as detrimental for neuronal homeostasis as CaV2 loss of function (47, 48), indicating that an optimal level of ongoing synaptic Ca2+ flux may be essential for homeostatic regulation. It remains to be seen whether the loss of functional GABABRs, associated with epilepsy and a wide range of psychiatric disorders (49), contributes to pathophysiology shared by these disorders through erasing critical pathways in homeostatic control systems.

Materials and Methods

Hippocampal Cell Culture.

Primary cultures of CA3-CA1 hippocampal neurons were prepared from WT, 1a−/−, and 1b−/− (BALB/c background) mice (21) on postnatal days 0–2, as described (50). The experiments were performed in mature (14–28 d in vitro) cultures. All animal experiments were approved by the Tel Aviv University Committee on Animal Care.

MEA Preparation and Recordings.

Cultures were plated on MEA plates containing 59 TiN recording and one internal reference electrodes [Multi Channel Systems (MCS)]. Electrodes are 30 µm in diameter and spaced 500 µm apart. Data were acquired using a MEA1060-Inv-BC-Standard amplifier (MCS) with frequency limits of 5,000 Hz and a sampling rate of 10 kHz per electrode mounted on an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope. Recordings were carried out under constant 37 °C and 5% CO2 conditions, identical to incubator conditions. Spike sorting and analysis are described in ref. 9 and in SI Appendix, Spike Sorting and Data Analysis.

Molecular Biology.

GB1aWT-, GB1aΔPCT-, GB2-, and CaV2.2-tagged proteins used throughout the study were constructed as described before (30). Synt1a (CSYS-5RK), Synt1aOpen, and Synt1aK253I are as described in ref. 27. W66A point mutation was introduced to silence YFP in the YFP-Synt1a-CFP construct (Fig. 4 D and E and SI Appendix, Fig. S11). BoNT/C1α-51-IRES-EGFP was designed and then generated by ProGen Israel, Protein and Gene Engineering Company. Transient cDNA transfections have been performed using Lipofectamine-2000 reagents, and neurons were typically imaged 18–48 h after transfection.

Estimation of Synaptic Vesicle Release Using FM Dyes.

Activity-dependent FM1-43 or FM4-64 styryl dyes have been used to estimate synaptic vesicle exocytosis and presynaptic plasticity, as described (22). The experiments were conducted at room temperature in extracellular Tyrode solution containing (in mM): NaCl, 145; KCl, 3; glucose, 15; Hepes, 10; MgCl2, 1.2; CaCl2, 1.2, with pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The extracellular medium contained nonselective antagonist of ionotropic glutamate receptors (kynurenic acid, 0.5 mM) to block recurrent neuronal activity. Synaptic vesicles were loaded with 15 μM FM4-64 in all of the experiments with GFP/CFP/YFP transfection, whereas 10 μM FM1-43 was used in all of the nontransfected neurons.

Detecting Presynaptic Calcium Transients.

Fluorescent calcium indicator Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 AM was dissolved in DMSO to yield a concentration of 1 mM. For cell loading, cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min with 3 μM of this solution diluted in a standard extracellular solution. Imaging was performed using FV1000 Olympus confocal microscopes, under 488 nm (excitation) and 510–570 nm (emission), using 500-Hz line scanning.

FRET Imaging and Analysis.

Intensity-based FRET imaging was carried as described before (22, 30). Donor dequenching resulting from the desensitized acceptor was measured from Cer/CFP emission (460–500 nm) before and after the acceptor (YFP) photobleaching. Mean FRET efficiency, Em, was then calculated using the equation Em = 1 − IDA/ID, where IDA is the peak of donor emission in the presence of the acceptor and ID is the peak after acceptor photobleaching.

Statistical Analysis.

Error bars shown in the figures represent SEM. Where applicable, the number of experiments (cultures) or the number of boutons is defined by n. All the experiments were repeated at least in three different batches of cultures. One-way ANOVA analysis with post hoc Bonferroni’s was used to compare several conditions. Student’s unpaired, two-tailed t test has been used in the experiments in which two different populations of synapses were compared. Student’s paired, two-tailed t test has been used in the experiments where before and after treatments were compared at the same population of synapses. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, nonsignificant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by European Research Council Starting Grant 281403 (to I. Slutsky), the Israel Science Foundation (398/13 to I.S.; 234/14 to I.L.), the Binational Science Foundation (2013244 to I. Slutsky; 2009049 to I.L.), Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A_152970 to B.B.), and the Legacy Heritage Biomedical Program of the Israel Science Foundation (1195/14 to I. Slutsky). I. Slutsky is grateful to the Sheila and Denis Cohen Charitable Trust and Rosetrees Trust of the United Kingdom for their support. I.V. is grateful to the TEVA National Network of Excellence in Neuroscience for the award of a postdoctoral fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1424810112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Hebb and homeostasis in neuronal plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10(3):358–364. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Homeostatic plasticity in the developing nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(2):97–107. doi: 10.1038/nrn1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis GW. Homeostatic control of neural activity: from phenomenology to molecular design. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:307–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marder E, Goaillard JM. Variability, compensation and homeostasis in neuron and network function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(7):563–574. doi: 10.1038/nrn1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis GW, Müller M. Homeostatic control of presynaptic neurotransmitter release. Annu Rev Physiol. 2015;77:251–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turrigiano G. Too many cooks? Intrinsic and synaptic homeostatic mechanisms in cortical circuit refinement. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:89–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazarevic V, Schöne C, Heine M, Gundelfinger ED, Fejtova A. Extensive remodeling of the presynaptic cytomatrix upon homeostatic adaptation to network activity silencing. J Neurosci. 2011;31(28):10189–10200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2088-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehlers MD. Activity level controls postsynaptic composition and signaling via the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(3):231–242. doi: 10.1038/nn1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slomowitz E, et al. Interplay between population firing stability and single neuron dynamics in hippocampal networks. eLife. 2015;4:e04378. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hengen KB, Lambo ME, Van Hooser SD, Katz DB, Turrigiano GG. Firing rate homeostasis in visual cortex of freely behaving rodents. Neuron. 2013;80(2):335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Leary T, Williams AH, Franci A, Marder E. Cell types, network homeostasis, and pathological compensation from a biologically plausible ion channel expression model. Neuron. 2014;82(4):809–821. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramocki MB, Zoghbi HY. Failure of neuronal homeostasis results in common neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Nature. 2008;455(7215):912–918. doi: 10.1038/nature07457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuler V, et al. Epilepsy, hyperalgesia, impaired memory, and loss of pre- and postsynaptic GABA(B) responses in mice lacking GABA(B(1)) Neuron. 2001;31(1):47–58. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prosser HM, et al. Epileptogenesis and enhanced prepulse inhibition in GABA(B1)-deficient mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;17(6):1059–1070. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.0995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gassmann M, et al. Redistribution of GABAB(1) protein and atypical GABAB responses in GABAB(2)-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24(27):6086–6097. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5635-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vienne J, Bettler B, Franken P, Tafti M. Differential effects of GABAB receptor subtypes, gamma-hydroxybutyric Acid, and Baclofen on EEG activity and sleep regulation. J Neurosci. 2010;30(42):14194–14204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3145-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badran S, Schmutz M, Olpe HR. Comparative in vivo and in vitro studies with the potent GABAB receptor antagonist, CGP 56999A. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;333(2-3):135–142. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turrigiano GG, Leslie KR, Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Nelson SB. Activity-dependent scaling of quantal amplitude in neocortical neurons. Nature. 1998;391(6670):892–896. doi: 10.1038/36103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murthy VN, Schikorski T, Stevens CF, Zhu Y. Inactivity produces increases in neurotransmitter release and synapse size. Neuron. 2001;32(4):673–682. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00500-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bettler B, Kaupmann K, Mosbacher J, Gassmann M. Molecular structure and physiological functions of GABA(B) receptors. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(3):835–867. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vigot R, et al. Differential compartmentalization and distinct functions of GABAB receptor variants. Neuron. 2006;50(4):589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laviv T, et al. Basal GABA regulates GABA(B)R conformation and release probability at single hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2010;67(2):253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobrunz LE, Stevens CF. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation, and depletion at central synapses. Neuron. 1997;18(6):995–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raingo J, et al. VAMP4 directs synaptic vesicles to a pool that selectively maintains asynchronous neurotransmission. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(5):738–745. doi: 10.1038/nn.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dulubova I, et al. A conformational switch in syntaxin during exocytosis: role of munc18. EMBO J. 1999;18(16):4372–4382. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acuna C, et al. Microsecond dissection of neurotransmitter release: SNARE-complex assembly dictates speed and Ca²⁺ sensitivity. Neuron. 2014;82(5):1088–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greitzer-Antes D, et al. Tracking Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent conformational transitions in syntaxin 1A during exocytosis in neuroendocrine cells. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 13):2914–2923. doi: 10.1242/jcs.124743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerber SH, et al. Conformational switch of syntaxin-1 controls synaptic vesicle fusion. Science. 2008;321(5895):1507–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1163174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao C, Dreosti E, Lagnado L. Homeostatic synaptic plasticity through changes in presynaptic calcium influx. J Neurosci. 2011;31(20):7492–7496. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6636-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laviv T, et al. Compartmentalization of the GABAB receptor signaling complex is required for presynaptic inhibition at hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci. 2011;31(35):12523–12532. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1527-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Müller CS, et al. Quantitative proteomics of the Cav2 channel nano-environments in the mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(34):14950–14957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005940107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varela JA, et al. A quantitative description of short-term plasticity at excitatory synapses in layer 2/3 of rat primary visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17(20):7926–7940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07926.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Modulation of transmission during trains at a cerebellar synapse. J Neurosci. 2000;20(4):1348–1357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01348.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee KJ, et al. Mossy fiber-CA3 synapses mediate homeostatic plasticity in mature hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2013;77(1):99–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J, Tsien RW. Synapse-specific adaptations to inactivity in hippocampal circuits achieve homeostatic gain control while dampening network reverberation. Neuron. 2008;58(6):925–937. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiagarajan TC, Lindskog M, Tsien RW. Adaptation to synaptic inactivity in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2005;47(5):725–737. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Branco T, Staras K, Darcy KJ, Goda Y. Local dendritic activity sets release probability at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2008;59(3):475–485. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burrone J, O’Byrne M, Murthy VN. Multiple forms of synaptic plasticity triggered by selective suppression of activity in individual neurons. Nature. 2002;420(6914):414–418. doi: 10.1038/nature01242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wierenga CJ, Walsh MF, Turrigiano GG. Temporal regulation of the expression locus of homeostatic plasticity. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96(4):2127–2133. doi: 10.1152/jn.00107.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bacci A, et al. Chronic blockade of glutamate receptors enhances presynaptic release and downregulates the interaction between synaptophysin-synaptobrevin-vesicle-associated membrane protein 2. J Neurosci. 2001;21(17):6588–6596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06588.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jakawich SK, et al. Local presynaptic activity gates homeostatic changes in presynaptic function driven by dendritic BDNF synthesis. Neuron. 2010;68(6):1143–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitra A, Mitra SS, Tsien RW. Heterogeneous reallocation of presynaptic efficacy in recurrent excitatory circuits adapting to inactivity. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(2):250–257. doi: 10.1038/nn.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Younger MA, Müller M, Tong A, Pym EC, Davis GW. A presynaptic ENaC channel drives homeostatic plasticity. Neuron. 2013;79(6):1183–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang T, Hauswirth AG, Tong A, Dickman DK, Davis GW. Endostatin is a trans-synaptic signal for homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2014;83(3):616–629. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu LG, Saggau P. GABAB receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition in guinea-pig hippocampus is caused by reduction of presynaptic Ca2+ influx. J Physiol. 1995;485(Pt 3):649–657. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dickman DK, Davis GW. The schizophrenia susceptibility gene dysbindin controls synaptic homeostasis. Science. 2009;326(5956):1127–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.1179685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frank CA, Kennedy MJ, Goold CP, Marek KW, Davis GW. Mechanisms underlying the rapid induction and sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis. Neuron. 2006;52(4):663–677. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Müller M, Davis GW. Transsynaptic control of presynaptic Ca²⁺ influx achieves homeostatic potentiation of neurotransmitter release. Curr Biol. 2012;22(12):1102–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gassmann M, Bettler B. Regulation of neuronal GABA(B) receptor functions by subunit composition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(6):380–394. doi: 10.1038/nrn3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slutsky I, Sadeghpour S, Li B, Liu G. Enhancement of synaptic plasticity through chronically reduced Ca2+ flux during uncorrelated activity. Neuron. 2004;44(5):835–849. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.