Significance

Hsp90 is a molecular chaperone involved in the activation of numerous client proteins, including 60% of the human kinases. Previous studies on the Hsp90–kinase interaction were limited due to the particular instability of client kinases. Here, we reconstituted v-Src kinase chaperoning in vitro and used this to mechanistically elucidate how Hsp90 supports kinases. We show that its activation is ATP-dependent and requires the phosphorylated form of the cochaperone Cdc37. Hsp90 does not influence the almost identical c-Src kinase. The structural analysis of Src kinase chimeras that gradually transformed c-Src into v-Src unveiled that Hsp90 dependence correlates with client compactness, folding cooperativity, and lowered energy barriers between different states. These findings establish a new concept for the client specificity of Hsp90.

Keywords: Cdc37, kinase activation, metastable states, conformational ensembles, chaperone mechanism

Abstract

Hsp90 is a molecular chaperone involved in the activation of numerous client proteins, including many kinases. The most stringent kinase client is the oncogenic kinase v-Src. To elucidate how Hsp90 chaperones kinases, we reconstituted v-Src kinase chaperoning in vitro and show that its activation is ATP-dependent, with the cochaperone Cdc37 increasing the efficiency. Consistent with in vivo results, we find that Hsp90 does not influence the almost identical c-Src kinase. To explain these findings, we designed Src kinase chimeras that gradually transform c-Src into v-Src and show that their Hsp90 dependence correlates with compactness and folding cooperativity. Molecular dynamics simulations and hydrogen/deuterium exchange of Hsp90-dependent Src kinase variants further reveal increased transitions between inactive and active states and exposure of specific kinase regions. Thus, Hsp90 shifts an ensemble of conformations of v-Src toward high activity states that would otherwise be metastable and poorly populated.

The 90-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90) is an abundant chaperone in the cytosol of eukaryotes (1). Together with its cochaperones, it functions in the conformational control of many regulatory proteins (2–4). Kinases constitute the largest group of Hsp90 client proteins with more than 60% of the human kinases that depend on Hsp90 in terms of their activity (5, 6).

Hsp90 forms V-shaped homodimers connected via a C-terminal domain. The middle domain (M-domain) is involved in client binding (7, 8), and the N-terminal domain binds ATP. Upon ATP binding, the N-terminal domains dimerize, leading to the closed state (9–13), whereas the open state is regained upon ATP-hydrolysis (14). Both conformation and ATPase activity are affected by interaction with a cohort of cochaperones (15). Given the large number and diversity of client proteins, cochaperones are believed to deliver specificity in this context.

The Hsp90-mediated maturation of kinases is strictly dependent on the cochaperone Cdc37 (cell division control protein 37) (16, 17) and phosphorylation of this cofactor is important for its function (18, 19). Binding of Cdc37 to Hsp90 causes inhibition of the ATPase activity of Hsp90 and has therefore been proposed to facilitate client kinase loading onto the Hsp90 machinery (20).

The viral Src kinase (v-Src) is one of the most stringent known Hsp90 clients (5, 21). v-Src belongs to the family of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases, which play important roles in many cellular pathways. v-Src kinase is constitutively active and leads to the formation of sarcomas in chicken (22). It shows 98% sequence identity with its cellular counterpart c-Src (cellular Src kinase), the first identified protooncogene (23). Hsp90 binds to and stabilizes c-Src in its nascent state, but it dissociates after the kinase folding is achieved (24). Due to this complete loss of interaction, c-Src has been defined as a nonclient (5). Src consists of a unique domain followed by the SH3 and SH2 domains and a flexible linker, which connects the SH2 domain with the highly conserved kinase domain. c-Src contains an additional stretch at its C terminus that includes a tyrosine at the position 527, whose phosphorylation status regulates kinase activity (25, 26). In addition, v-Src differs from c-Src by several point mutations (27–30). Some of these were shown to increase c-Src activity in vivo and have been linked to cancer progression and metastasis in humans (31–33). Due to these differences, v-Src cannot be down-regulated and is permanently active, even in the absence of activating stimuli (26, 30). The analysis of proteins nearly identical in sequence but highly different in chaperone dependence offers an excellent model system for understanding the features that render a protein Hsp90-dependent. We used these kinases to reconstitute and dissect the chaperoning effect of Hsp90 on v-Src kinase in vitro. The analysis of chimeras comprising elements of c-Src and v-Src allowed us to determine the molecular basis of the stringent Hsp90 dependence of v-Src.

Results

Hsp90-Dependent Chaperoning of v-Src in Vitro.

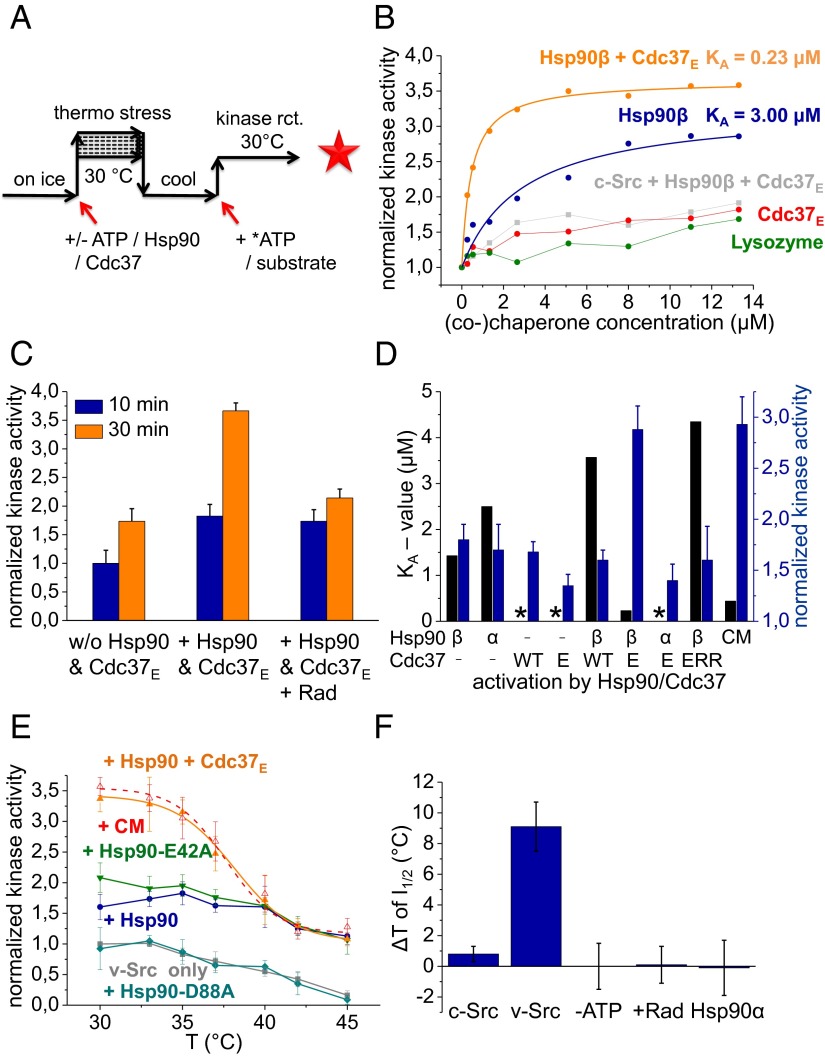

It is well established that v-Src kinase activity is strictly Hsp90-dependent in vivo (5, 34). Furthermore, v-Src requires the Hsp90 cochaperone Cdc37 to reach full activity in the cell (21, 35). Strikingly however, Hsp90 does not affect the highly homologous cellular form of v-Src, c-Src (21). We aimed to reconstitute the effects of Hsp90 on v-Src activity in vitro. To this end, we purified the v-Src and c-Src kinases from insect cells and determined the influence of Hsp90 on their activity (Fig. 1). When we tested the effect of Hsp90 on c-Src kinase, we could not observe a significant change in its activity (Fig. 1B). In contrast, for v-Src, the presence of Hsp90 resulted in a twofold increase in activity (Fig. 1B). This effect is ATP-dependent as shown by the addition of the Hsp90 inhibitor Radicicol during the reaction (Fig. 1C), in which the activity of v-Src decreased to its basal, Hsp90-independent level. This shows that activation is constantly dependent on Hsp90. Interestingly, only the human Hsp90 isoform, Hsp90β, but not the Hsp90-α isoform, was active in chaperoning v-Src kinase (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

In vitro influence of Hsp90 on Src kinases. (A) Assay scheme of in vitro stabilization and activation of Src kinases by chaperones. Before transphosphorylation, kinases were preincubated for 10 min on ice in the presence or absence of Hsp90 (and/or Cdc37 variants) and 20 µM ATP followed by 10 min at increasing temperatures (stabilization) or 30 °C (activation) and 10-min incubation on ice. Following, 10-fold excess (3.2 µM) of denatured enolase substrate and 20 µM of radioactively labeled ATP were added, and the reaction was incubated for 30 min at 30 °C to measure kinase activity. (B) v-Src kinase activation by chaperones in vitro. The normalized kinase activities were calculated by dividing the detected activities by the activity of the respective kinase alone. Hsp90β (blue) and Cdc37-S13E (Cdc37E) (red) were titrated either alone or in combination (orange) to v-Src kinase and compared with a lysozyme control (green). Hsp90β together with Cdc37E had no significant effect on c-Src (gray). (C) Effect of Radicicol on the ability of 1.3 µM Hsp90 to activate 320 nM v-Src. Ten minutes after starting the kinase reaction, 250 µM Radicol was added and kinase activity was analyzed after 30 min. Here, all detected activities were normalized to the value of v-Src alone after 10 min. The error bars represent the SD of three independent experiments. (D) Activation of v-Src by different combinations of Hsp90β (β) or Hsp90α (α) and Cdc37E (E), Cdc37WT (WT), a non–Hsp90-binding Cdc37 mutant [Cdc37-S13E-M164R-L205R, Cdc37ERR (ERR)], and a chaperone mix including Hsp90β, Cdc37E, Hdj-1 (Hsp40), Hsp70, and Hop (CM). Depicted are the activation constants KA (black bars) and the normalized kinase activity at a (co)chaperone concentration of 1.3 µM (blue bars). A black asterisk indicates activation curves for which no activation constant was calculable. (E) Influence of chaperones on v-Src during exposure to elevated temperatures. v-Src was incubated at different temperatures with 20 µM ATP in the absence (gray) or presence of 1.3 µM Hsp90 (blue), Hsp90-E42A (olive), Hsp90-D88A (cyan), 1.3 µM Hsp90 and 1.3 µM Cdc37 (orange), or the chaperone mix (red). (F) Stabilization of c-Src and v-Src by Hsp90 and ATPase dependence of the process. Plotted are the changes in the temperature (ΔT) of half-maximal inactivation (I1/2). Leaving out ATP or addition of the Hsp90 inhibitor Radicicol during the preincubation steps compromised the ability of Hsp90 to rescue v-Src from inactivation. Unlike Hsp90β, Hsp90α was not able to stabilize v-Src.

The kinase-specific cochaperone Cdc37 alone or in combination with Hsp90 had no effect on v-Src activity (Fig. 1D). However, in vivo experiments had suggested that phosphorylation of Cdc37 is involved in regulating its function (19, 36). When we used a Cdc37 variant in which the phosphorylation was mimicked by a glutamate substitution (Cdc37E), also this variant alone had no significant influence on v-Src (Fig. 1B), but together with Hsp90, we observed a threefold increase in its activity at a chaperone concentration of 1.3 µM (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1A). Importantly, the combination of Hsp90 and Cdc37E increased the apparent affinity toward the kinase by roughly 15-fold, reflected by the activation constants, KA, obtained by a Michaelis–Menten fit. For Hsp90β, we obtain a KA value of 3.0 μM, whereas for the combination of Hsp90β and Cdc37E, the KA value decreased to 0.23 μM (Fig. 1B). Phosphorylated wild-type Cdc37 had the same effect. This increase in apparent affinity could result from the independent action of Hsp90 and Cdc37E. To test whether the interaction between the two proteins is required, we made use of a Cdc37E mutant defective in Hsp90 binding (37) (Cdc37ERR). We found that this variant was incapable of kinase activation in the presence of Hsp90, suggesting that the formation of a complex between Cdc37 and Hsp90 is important for activating v-Src (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1B).

We could not observe a significant increase in activation by the addition of the Hsp70 chaperone system (Hsp70, Hsp40, and Hop) to v-Src kinase (Fig. 1 D and E). These findings suggest that, in this setup, Hsp90β together with phosphorylated Cdc37 are the key players responsible for activating the client kinase.

It is established that v-Src is less stable than c-Src against thermal unfolding (38). We thus asked whether Hsp90 could stabilize v-Src kinase at elevated temperatures. To this end, we incubated v-Src at different temperatures with Hsp90 or with both Hsp90 and Cdc37E (Fig. 1A). With increasing temperatures, v-Src alone rapidly lost its activity compared with c-Src (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1C). The presence of ATP had no influence on kinase stability under these conditions. However, in the presence of Hsp90β (but not Hsp90α), the loss of kinase activity was prevented. For that, a concentration of 1.3 µM Hsp90 was sufficient (Fig. S1D).

Remarkably, this stabilizing effect became Cdc37-independent at higher temperatures (Fig. 1E) as the two curves converge at around 40 °C. The presence of the Hsp70 chaperone system had no influence on the action of Hsp90 (Fig. 1E).

To analyze how Hsp90 couples ATP binding and hydrolysis to v-Src activation and stabilization, we used two well-characterized ATPase-deficient variants of human Hsp90β and tested them for activation of v-Src kinase (Fig. 1E). Hsp90-E42A binds ATP but does not hydrolyze it. Hsp90-D88A on the other hand neither binds nor hydrolyzes ATP (39, 40). Both variants showed a similar stability compared with wild-type Hsp90 (Fig. S1E). Analysis of these Hsp90 mutants showed that Hsp90-D88A in combination with Cdc37E did not affect v-Src activity, whereas Hsp90-E42A was able to activate v-Src approximately twofold at 30 °C (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, we found that Hsp90-D88A could not stabilize v-Src (Fig. 1E), which is in agreement with the necessity of ATP for this reaction (Fig. 1F). Intriguingly, Hsp90-E42A was able to stabilize v-Src similar to wild-type Hsp90 (Fig. 1E).

In the presence of Hsp90, the temperature of half-maximal inactivation I1/2 was shifted by 9 °C (Fig. 1F), and the apparent stability corresponded to that of c-Src (Fig. S1C). For c-Src, the presence of Hsp90 did not affect the inactivation process (Fig. 1F). The stabilizing effect of Hsp90β on v-Src was dependent on the presence of ATP and could be suppressed by the addition of Radicicol (Fig. 1F). In summary, we observed that, for stabilization of v-Src during heat exposure, ATP binding by Hsp90 is sufficient. However, for activation of v-Src under physiological conditions, both the presence of the cochaperone Cdc37E and ATP hydrolysis by Hsp90 is needed.

Src Chimeras Reveal Client Features of v-Src.

Having reconstituted the Hsp90-dependent chaperoning of v-Src kinase in vitro, we probed factors that render v-Src a chaperone client but leave c-Src unaffected.

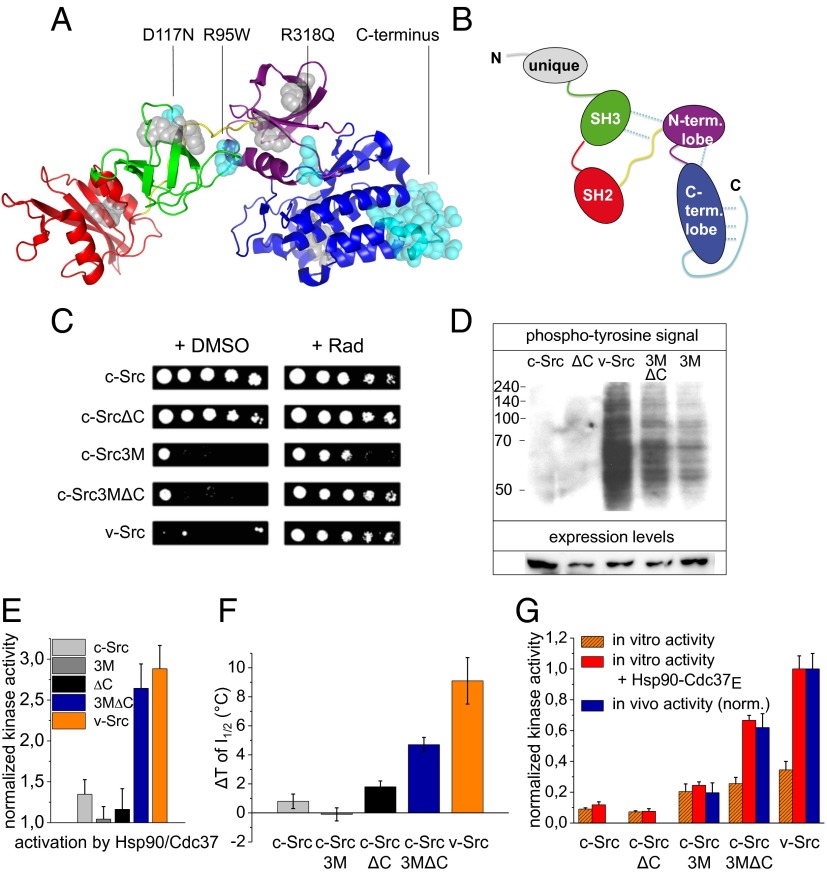

v-Src differs from its cellular isoform c-Src in only a few amino acids and in the absence of the C-terminal tail (Fig. 2 A and B). Specifically, three mutations have been shown to be responsible for the transforming potential of v-Src (31–33). These point mutations are located in the SH3–linker–kinase domain interface. To determine how these changes affect the function of the kinase as well as its structure and Hsp90 dependence, we created chimeras of c-Src. In the c-Src variant c-Src3M, three residues were exchanged for their respective residues in v-Src (R95W, D117N, and R318Q). Furthermore, we created a c-Src variant, in which the C-terminal tail of c-Src was deleted (c-SrcΔC) and finally combined both elements in the variant c-Src3MΔC. To test the activity of the generated c-Src mutants in vivo, we expressed these variants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. v-Src is known to be highly toxic for yeast, whereas c-Src does not affect yeast growth (21). We were able to reproduce these findings and show that the expression of c-Src3M and c-Src3MΔC led to a reduced growth of yeast, although to a lesser extent compared with v-Src (Fig. 2C). c-SrcΔC did not affect yeast viability. Apparently, the three introduced point mutations are responsible for the compromised growth observed in yeast. To test for a possible Hsp90 dependence of the Src variants, cells were analyzed in the presence of the Hsp90 inhibitor Radicicol (Fig. 2C). Upon Hsp90 inhibition, yeast cells exhibited less pronounced lethality in the case of c-Src3M and normal growth upon expression of v-Src and c-Src3MΔC. Thus, the toxic effect of c-Src3MΔC and v-Src was much more Hsp90-dependent than that of c-Src3M, and Hsp90 dependence is largely caused by the combination of the three point mutations and the missing C-terminal tail in v-Src. To further investigate Src kinase activity in vivo, we analyzed the presence of phosphotyrosines in yeast proteins (Fig. 2D). For c-Src and c-SrcΔC, no phosphotyrosines were detectable. However, for c-Src3M, c-Src3MΔC, and v-Src, a distinct phosphorylation pattern appeared. The intensity increased from c-Src3M to c-Src3MΔC with v-Src exhibiting the most pronounced effects. Interestingly, in vivo activity did not seem to correlate with protein abundance (Fig. 2D). The expression of the toxic c-Src3M mutant was increased, although this kinase showed less activity relative to the c-Src3MΔC and v-Src variants. Furthermore, the mutants with a deleted C-terminal tail were less abundantly expressed, indicating a lower stability of these constructs (Fig. 2D). To further investigate the in vivo stability of the kinases, we performed a pulse chase experiment and analyzed the protein levels. We found that v-Src showed a strongly and c-Src3MΔC showed a slightly reduced half-life during the time course compared with c-Src (Fig. S2). Interestingly, analyzing the stability of the constructs in a Cdc37-knockdown background revealed that the variants c-Src3M, c-Src3MΔC, and v-Src exhibited a significant dependence on Cdc37 with c-Src3M showing less Cdc37 dependence than c-Src3MΔC and v-Src. The Hsp90-independent variants c-Src and c-SrcΔC were not affected by the Cdc37 knockdown (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Design of a Hsp90 client kinase. (A) Structure of c-Src (PDB ID 1Y57) (66). Coloring from N to C terminus: SH3 domain in green, SH2 domain in red, linker connecting SH2 domain and N-lobe of the kinase domain in yellow, kinase domain N-lobe in violet, and C-lobe in blue. Tryptophan residues are depicted as gray spheres. The mutated or deleted residues in the c-Src variants are depicted as blue spheres. (B) Schematic representation of c-Src. Colors are the same as in the crystal structure. The unique domain, which is missing in the crystal structure, is shown in gray. Intramolecular contacts made by the mutated residues are represented by dotted light blue lines. (C) Serial dilutions of S. cerevisiae expressing different Src variants in the absence or presence of the Hsp90 inhibitor Radicicol in the medium. (D) In vivo activity of Src kinases were tested by detecting phosphotyrosines in yeast lysates. In addition, expression levels were determined by a Src-specific antibody. (E) Activation of Src variants by 1.3 μM Hsp90β and Cdc37E. (F) Stabilization of Src variants by 1.3 µM Hsp90β is represented as the shift of the temperature of half-maximal inactivation. (G) Comparison of v-Src chaperoning in vivo and in vitro. Shown are the in vitro activities of Src variants alone (orange) and their Hsp90/Cdc37E-dependent in vitro-activated activities (red) in comparison with their in vivo activities normalized to their respective expression levels.

Next, we tested the different Src variants for their potential to be activated by Hsp90 and Cdc37E in vitro. We found that v-Src and c-Src3MΔC were readily activated, whereas, in accordance with the in vivo results, c-Src, c-SrcΔC, and c-Src3M showed only low activation potential (Fig. 2E). This was consistent with the observation of a lower in vivo activity of c-Src3M regardless of its robust expression. A similar picture emerges at elevated temperatures: c-Src3M and c-SrcΔC were not significantly stabilized, and, in contrast, the inactivation of c-Src3MΔC and v-Src was strongly affected by Hsp90 (Fig. 2F and Fig. S1C). To further evaluate the effect of Hsp90 and Cdc37 in vivo and in vitro, Fig. 2G shows the in vivo activities of the different variants normalized to their respective expression level in comparison with their in vitro activities in the presence and in the absence of Hsp90 and Cdc37E. Notably, the in vitro analysis faithfully recapitulates in vivo effects and the ratios of the activities for the different variants in the presence of Hsp90 and Cdc37E reflect the ratios of the in vivo activities.

What Renders a Kinase Hsp90-Dependent?

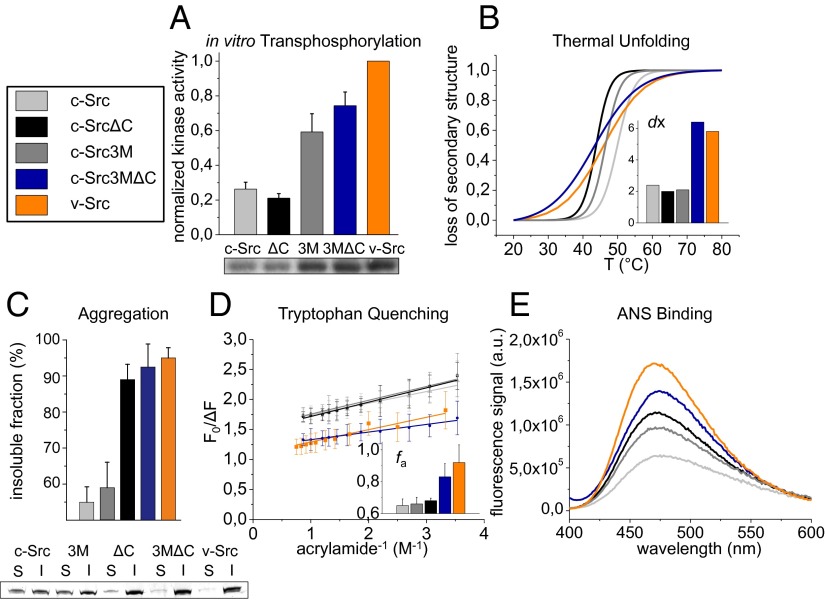

Our set of mutants allowed us to define characteristics that correlate with differences in Hsp90 dependence. When comparing the activity of the different Src variants, we found that isolated v-Src has a fourfold higher activity than c-Src (Fig. 3A). In agreement with results from the in vivo activity (Fig. 2D), deletion of the C-terminal tail in c-Src did not significantly alter the activity of the kinase. Introduction of the three point mutations (c-Src3M), however, led to a nearly 2.5-fold activation of c-Src, whereas the combination of the amino acid substitutions and the C-terminal deletion (c-Src3MΔC) gave rise to a threefold increase. It is noteworthy that c-Src and c-SrcΔC did not show detectable activity in yeast but were active as purified proteins in vitro. Overall, the activities of the three toxic kinase variants were comparably increased in vitro. Consistent with the literature, the KM of c-Src for ATP was in the ∼13 µM range (41) (Table 1). We found that the KM of c-SrcΔC was slightly increased to about ∼20 µM. Notably, all Src variants carrying the three point mutations showed a threefold to fivefold increase in the ATP affinity with KM values of ∼4 µM.

Fig. 3.

Biophysical characterization of Src variants. (A) In vitro transphosphorylation signal of 320 nM Src variants and the corresponding SDS/PAGE autoradiograph. (B) Stability and unfolding cooperativity of 1.6 µM Src variants measured by CD spectroscopy. Thermal transitions were recorded at 222 nm. The Inset shows the dx values of the Boltzmann plot. (C) Analysis of aggregation propensity. Src variants at a concentration of 1.6 µM were incubated for 10 min at 45 °C, and soluble and insoluble fraction separated by SDS/PAGE and densitometrically quantified. (D) Quenching of tryptophan fluorescence. Acrylamide was titrated to 500 nM Src variants and fluorescence emission after excitation at 295 nm was monitored at 340 nm. Shown are modified Stern–Volmer plots for the different Src mutants. In the Inset, the fa values representing the accessibility of tryptophans are plotted for the different proteins. (E) Analysis of ANS binding to hydrophobic protein patches. The 20 µM ANS was incubated with 1.6 µM Src variants, and fluorescence spectra after excitation at 380 nm were recorded and buffer corrected.

Table 1.

Characteristics of investigated Src variants

| Src variant | I1/2, °C | TM, °C | dx, value of unfolding | Aggregation, % | Tryptophan accessibility, fa | ANS fluorescence, 105 a.u. | KM for ATP, µM |

| c-Src | 49.5 | 50 | 2.4 | 55 | 0.65 ( 0.041) | 6.48 | 12.8 ( 1.4) |

| c-Src3M | 45.1 | 46.5 | 2.1 | 58 | 0.68 ( 0.017) | 9.73 | 4.9 ( 0.8) |

| c-SrcΔC | 38.8 | 44 | 2.0 | 89 | 0.66 ( 0.042) | 11.46 | 19.8 ( 3.6) |

| c-Src3MΔC | 33.3 | 43.5 | 6.4 | 92.5 | 0.83 ( 0.083) | 13.91 | 4.0 ( 0.7) |

| v-Src | 40.2 | 46 | 5.8 | 95 | 0.92 ( 0.111) | 17.17 | 4.0 ( 0.8) |

| c-Src-K295R | — | 51 | 1.7 | 44 | 0.64 ( 0.037) | 8.35 | — |

| v-Src-K295R | — | 32.6 | 9.2 | 99.8 | 0.79 ( 0.033) | 19.34 | — |

To determine the stability of the Src variants, we incubated each of them at elevated temperatures and measured their activities. In agreement with previous results (38), c-Src lost its activity at higher temperatures compared with v-Src (Fig. S1A). The temperature of half-maximal kinase activity (I1/2) was 49.5 °C for c-Src and 40.2 °C for v-Src (Table 1). The C-terminal tail contributes significantly to the loss of activity of v-Src already at moderate temperatures. The additional three single amino acid substitutions (c-Src3MΔC) destabilized the protein even further with an I1/2 of 33.3 °C. Hence, grafting of v-Src elements onto c-Src kinase generally decreases kinase activity at elevated temperatures. In this context, the C-terminal tail deletion seems to play a pivotal role, with a loss of stability of at least 10 °C observed for all C-terminally deleted kinase variants.

The structural changes of the Src variants during thermal unfolding were monitored by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy (Fig. 3B and Table 1). We found that c-Src was most stable with a melting temperature (TM) of 50 °C, whereas the TM for v-Src was 46 °C. The c-SrcΔC mutant showed a TM of 44 °C, and the c-Src3M mutant exhibited an unfolding behavior in-between those observed for c-Src and v-Src. v-Src and the mutant c-Src3MΔC showed remarkably low cooperativities, as indicated by the less sigmoidal melting curves, and had already begun to unfold around 20 °C. Interestingly, the unfolding process was completed only above 70 °C. Thus, deletion of the C-terminal tail in v-Src contributes mainly to the observed instability at lower temperatures, whereas the combination of the point mutations and the C-terminal deletion strongly decrease the cooperativity of unfolding. This revealed a correlation between the unfolding cooperativity of the kinases and their respective in vivo Hsp90 dependence: the two stringent client kinases v-Src and c-Src3MΔC unfolded over a broad temperature range, which is reflected in the high dx values of 6.4 and 5.8 of the Boltzmann fits for c-Src3MΔC and v-Src, respectively. For the less Hsp90-dependent constructs c-Src, c-SrcΔC, and c-Src3M, this value was in the range of 2.0 (Fig. 3B, Inset, and Table 1). Consistent with previous findings (5), we observed a regain of cooperativity by the addition of a kinase inhibitor.

Separating the Src variants incubated at 45 °C into soluble and insoluble fractions revealed that, although one-half of the c-Src protein remained soluble, 95% of v-Src was found in the insoluble fraction (Fig. 3C). The two Src variants missing the C-terminal tail behaved similar to v-Src. Analogous to c-Src, 58% of the c-Src3M protein was found in the insoluble fraction. Thus, deletion of the C-terminal tail led to increased aggregation propensity, suggesting that the point mutations alone did not influence the aggregation of c-Src.

To gain further insight into conformational changes, we analyzed the accessibility of tryptophan residues in the Src variants. In Src kinase, tryptophans are widely distributed across the protein (Fig. 2A, gray spheres). Higher molecular flexibility will result in an increased exposure of these hydrophobic residues to quenchers like acrylamide (42). Modified Stern–Volmer plots revealed the corresponding accessibility factors, fa, of the analyzed Src variants (Fig. 3D). The fa value of v-Src was 0.92 and the one corresponding to c-Src3MΔC was 0.83, indicating that in these variants most of the tryptophan residues were readily accessible to the quenching molecules. c-Src and the c-Src3M and c-SrcΔC mutants had an fa value of 0.6–0.7, suggesting that the tryptophan residues were more buried in these proteins.

Investigation of surface hydrophobicity revealed that the three point mutations only led to a moderate increase in 1-anilino-8-naphthalene sulfonate (ANS) binding (Fig. 3E). However, in accordance with the aggregation behavior, the kinase variants lacking the C-terminal tail exhibited considerably stronger ANS binding, arguing for an increased exposure of hydrophobic patches (Fig. 3E).

Taken together, our results suggest that the point mutations together with the C-terminal tail deletion in v-Src destabilize the protein and reduce its rigidity, thereby increasing hydrophobicity and aggregation propensity.

Particular Regions Are Exposed in Hsp90 Client Kinases.

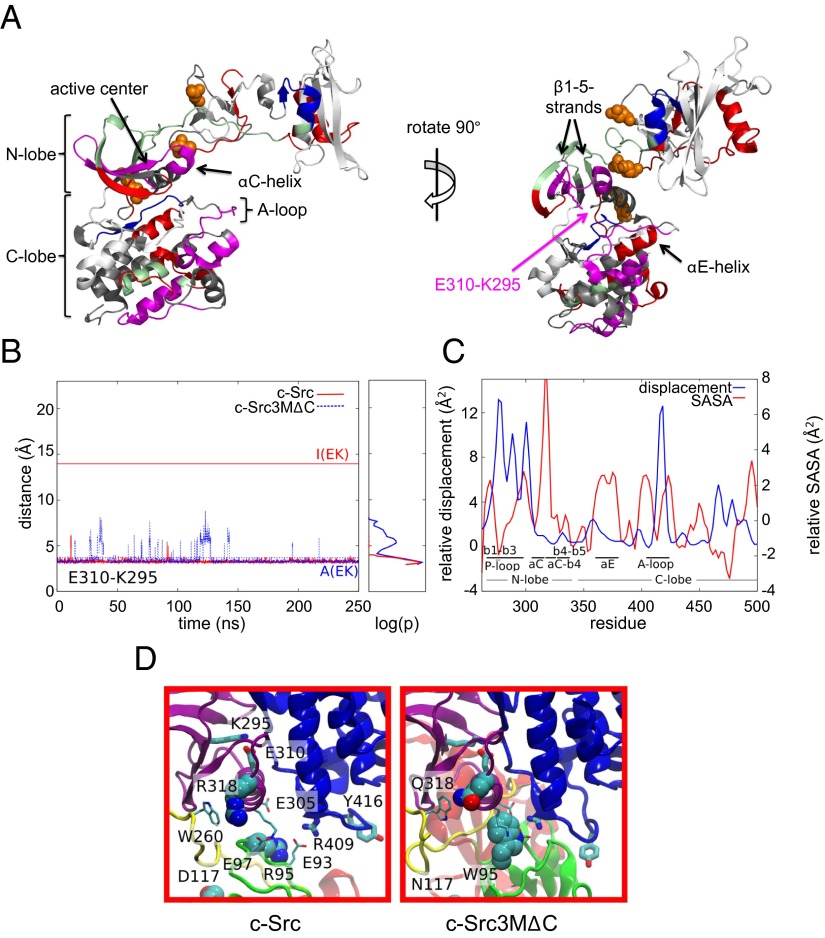

To intimately compare Hsp90 client and nonclient kinase conformations, we used hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange experiments. For this, we used the catalytically inactive v-Src mutant v-SrcK295R (43), due to significantly increased protein yields. Its characterization in comparison with v-Src, c-Src, and c-SrcK295R by our established set of methods revealed that, although minor differences were observed, this version sufficiently resembled wild-type v-Src properties (Fig. S3 A–D and Table 1). We determined the regions of v-SrcK295R with increased H/D exchange relative to the non-Hsp90 client c-Src and the weak Hsp90 client c-Src3M (Fig. 4A, Figs. S4–S8, and Table S1). For c-Src3M, these regions are located in the SH2 domain, in the kinase linker, and around the active center, including the active-site residues as well as the αC-helix, the αC-β4–loop, the β1-, β2-, and β3-strands, and the β4- and β5-strands (Fig. 4A). Moreover, we observed an increased exchange in the A-loop region, including the site of autophosphorylation Tyr416, and around the C-terminal part of the kinase domain.

Fig. 4.

Surface-exposed regions and dynamics of client kinases. (A) Hydrogen/deuterium exchange of Src variants. Increased exchange in c-Src3M compared with c-Src in pale green and blue, increased exchange in v-SrcK295R compared with c-Src in red and regions overlapping with c-Src3M in pale green, increased exchange in v-SrcK295R compared with c-Src3M in magenta. The Glu310–Lys295 ion pair is depicted as stick model. The three point mutations in c-Src3M and v-Src are depicted as orange spheres. (B) The dynamics of Glu310–Lys295 distances in c-Src (red) and c-Src3MΔC (blue). The Glu310–Lys295 distances are 3.4 and 14.0 Å in the active [A(EK)] and inactive [I(EK)] states of c-Src, respectively. (C) Difference in c-Src3MΔC vs. c-Src displacement and solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) for the kinase domain. The SASA was calculated as the average over the 250-ns runs for the complete residues. The displacement was calculated from the displacement of the Cα position obtained from end point structures at 250 ns. (D) Structural features of the active-site region of c-Src3MΔC and c-Src.

Strikingly, the exposed regions in v-Src almost completely overlap with those of c-Src3M (Fig. 4A). However, we observe additional exposed parts in v-Src and even higher solvent accessibility in the regions that are crucial for kinase activation, which include the active center region containing the αC-helix, the P-loop, and the β1- to β3-strands of the kinase domain N-lobe. The accessibility of the A-loop and of the C-terminal part of the kinase domain is increased in v-Src over c-Src3M. In addition, in v-Src also the αE-helix is more accessible (Fig. 4A).

To probe intrinsic dynamics of the proteins, we performed classical atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on the in silico mutated Src variant c-Src3MΔC and compared these to MD simulations of wild-type c-Src. The dynamics of the central Glu310-Lys295 ion pair, and the activation-loop (A-loop) region represent dynamical indicators of the kinase activation process (44, 45), which we use here to address the underlying molecular mechanism for the remarkable increase in activity and loss of stability in v-Src. For the c-Src model, we find that the Glu310–Lys295 ion pair remains closed for most of the 250-ns simulation (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the structure is trapped in the active state. This finding is consistent with the 4 kcal⋅mol−1 activation barrier recently estimated by Shukla et al. (46). In contrast, for the c-Src3MΔC variant, we observe several transient dissociation events of the Glu310–Lys295 ion pair (Fig. 4B), and a consistent shortening of the Glu310–Arg409 distance, indicating fluctuations between active and inactive states. Our simulations also suggest conformational changes in the A-loop region in c-Src3MΔC relative to c-Src, indicating significant displacement and partial unfolding (Fig. 4C). Moreover, we observe a subtle outward tilting of the αC-helix and an increase in the solvent accessibility and residue flexibility of the active-site and the A-loop regions (Fig. 4C), which may affect the accessibility for substrate binding. Similarly, the β1-, β2-, and β3-strands show increased displacement and surface exposure, and, consistent with our H/D exchange data, the αE-helix seems to be more flexible compared with c-Src (Fig. 4C). The MD simulations can reveal possible reasons for the distinct behavior of the c-Src3MΔC variant relative to c-Src. In the c-Src simulation, Arg95 forms ion pairs with two glutamate residues (Glu305 and Glu93), which are involved in stabilizing the αC-helix and Arg409 of the A-loop (Fig. 4D). The R95W mutation leads to interaction between Arg409 and Trp95, and partial dissociation of the Arg95–Glu305/Glu93 ion pairs, thus destabilizing the αC-helix and A-loop regions. We also observe that the interaction between Arg318, at the end of the αC-helix, with Trp260 is weakened by replacement with Gln318, which is likely to contribute to the flexibility of the helix and further increase of the rate of H/D exchange.

Discussion

The Conformational Activation of v-Src Kinase.

In vivo, the Hsp90 machinery activates v-Src kinase. Reconstitution of the chaperone effect in vitro shows that, although Hsp90 alone is able to increase v-Src activity, Cdc37 strongly enhances this effect. The affinity of Hsp90 toward the kinase is increased in the presence of Cdc37 about 15-fold, resulting in an apparent affinity of 0.23 μM. We assume the physiological concentration of Hsp90 to be in the low micromolar range, and the concentration of Cdc37, midnanomolar (47, 48). Cdc37 thus allows Hsp90 to interact with kinases in the cell under normal growth conditions. Consistent with the literature (36), we find that the phosphorylated form of Cdc37 is required for efficient activation of v-Src, without going through phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycles. Furthermore, we show that the formation of the Cdc37–Hsp90 complex is mandatory for v-Src activation. Although this finding is in agreement with the need of the Hsp90–Cdc37 interaction for kinase-dependent cell proliferation (49), alternative pathways for certain kinases may exist (37). In this context, the affinity of a kinase for ATP does not seem to correlate strictly with its chaperone dependence as different effects were observed for B-Raf kinase (50) and the Src kinase pair studied here. The finding of an Hsp90-isoform specificity of v-Src implies that the client spectrum of Hsp90β and Hsp90α may differ, as Hsp90α has been shown to be able to activate other kinases (51).

Chaperoning of v-Src at Elevated Temperatures.

Under thermal stress, a different picture emerges for the effect of Hsp90 on v-Src kinase. Here, Hsp90 alone stabilizes v-Src in a reaction where ATP binding, but not hydrolysis, is crucial. Notably, Cdc37 does not seem to be required for Hsp90 to stabilize v-Src. At around 38 °C, we observed a transition point for the shift from the Hsp90-Cdc37–mediated activation toward an Hsp90-dependent stabilization.

In summary, we found that for stabilization at elevated temperatures ATP binding is sufficient. However, for activation of v-Src under physiological conditions (30 °C), both the presence of the cochaperone Cdc37E and ATP hydrolysis by Hsp90 is needed. If only ATP binding is possible, kinase activation is inefficient.

The observed stabilizing effect might require different interactions of v-Src with Hsp90 for which Cdc37 is dispensable (Fig. 5). It is tempting to speculate that the thermal destabilization of v-Src kinase leads to the accumulation of a kinase conformation with increased affinity for Hsp90, and this may bypass the initial step of Cdc37 association. Of note, in yeast, only Hsp90 and the cochaperones Sti1 (stress-inducible protein) and Cpr6, but not Cdc37 are up-regulated under heat shock (52). Also, a Cdc37-independent association of Hsp90 with kinases was previously observed (50), and Cdc37 is not present in all organisms (53), suggesting a distinct role of Hsp90 in client kinase maturation.

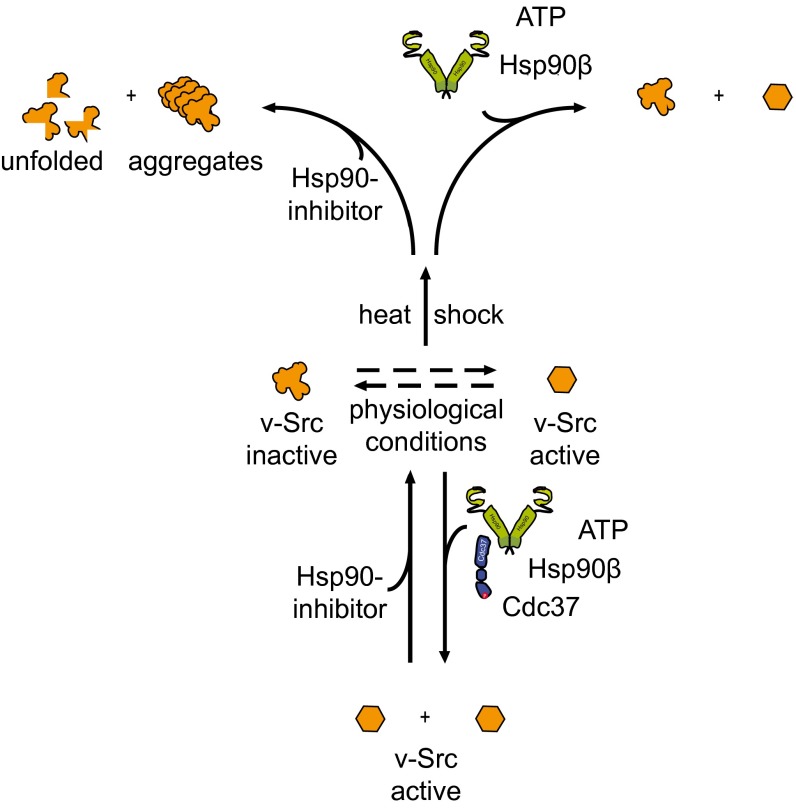

Fig. 5.

A model for kinase maturation by Hsp90. Client kinases exist in an equilibrium of metastable and stabilized states. Unfolding stress and intrinsic instability shift the equilibrium toward the less active state. Hsp90 stabilizes and maturates the kinase toward its active state. Cdc37 is able to enhance Hsp90’s affinity toward the kinase. Inhibition of Hsp90 prevents the process and leads to kinase inactivation, aggregation, or degradation.

Identifying the Characteristics of an Hsp90 Client.

ATP binding and hydrolysis by Hsp90 is a prerequisite for kinase activation under physiological conditions. We found that generating and maintaining the activated state of v-Src is strictly dependent on the continued ATPase cycle of Hsp90 as its inhibition decreases kinase activity to its basal Hsp90-independent level. This implies that the kinase molecules are constantly activated by the chaperone. We propose that Hsp90/Cdc37 shift the conformational ensemble of different activation states toward a more active distribution.

To figure out which properties of a protein render it a client for Hsp90, we made use of the few sequence differences between the v-Src and c-Src kinase pair. By grafting of client elements onto the scaffold of the nonclient c-Src kinase and comparing the characteristics of the chimeras, we could identify structural properties that cause chaperone dependence. Interestingly, the deletion of the regulatory C-terminal tail in c-SrcΔC, which is the primary reason for the conversion of c-Src to a transforming protein in mammals (54), did not result in increased Hsp90 dependence in vivo and in vitro. Nevertheless, c-SrcΔC showed a significantly decreased stability compared with the wild-type c-Src kinase, as well as a high aggregation propensity. Thus, these properties per se are not sufficient for defining a protein an Hsp90 client.

Another c-Src variant, carrying three point mutations (c-Src3M) that are relevant for the development of transforming properties in cancer (31–33), was toxic in yeast as well as the combination of the C-terminal tail deletion and the three point mutations (c-Src3MΔC). However, only the latter chimera was similarly Hsp90-dependent as v-Src.

To resolve this conundrum, we aimed to define the structural differences between the variants. We found that the introduction of v-Src elements into c-Src leads to a general decrease in stability. However, only the two strong Hsp90 clients c-Src3MΔC and v-Src show remarkable low unfolding cooperativity, indicating that the protein is flexible and may exist in an ensemble of folded structures. Furthermore, the Hsp90 dependence correlates with an increased surface hydrophobicity. This finding is in agreement with the notion of increased structural dynamics and molecular compactness of the Hsp90 client. Of note, the three mutations and the deletion of the C-terminal tail did not fully convert c-Src into v-Src with respect to Hsp90 dependence and its biophysical qualities. In addition to the altered C-terminal tail, v-Src in total carries 11 point mutations compared with c-Src that might well be involved in causing the differences.

In summary, a combination of qualities seems to cause Hsp90 dependence: client kinases are destabilized, aggregation prone, with hydrophobic, less compact structures, and can hence be designated as metastable proteins.

Exposure of Key Kinase Regions Determines Hsp90 Dependence.

The backbone hydrogen/deuterium exchange experiments showed a significant increase in the dynamics of regions that are located within previously suggested chaperone binding sites. These include the glycine-rich P-loop, the αC-helix, the adjacent loop (αC-β4–loop), as well as the β1- to β5-strands, all located in the N-lobe of the kinase domain (55–58). In addition to the increased exposure of these sites, the P-loop and the αE-helix are more accessible in v-Src compared with c-Src and c-Src3M, which could account for the differences in response to Hsp90.

Our molecular dynamics simulations confirm these notions and extend the picture. Specific regions show increased exposure and/or flexibility including the αC-helix, the proximal portion of the αC-β4–loop, and the αE-helix, consistent with the H/D exchange data. Because the P-loop is rich in glycines, the overall solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) is small for this region. Nevertheless, there seems to be a structural difference, as indicated by the peak in displacement.

The increased “active-to-inactive” transitions in the c-Src3MΔC variant suggest that the kinetic barrier for activation is effectively lowered, which might explain the experimentally observed increased activity and conformational flexibility in c-Src3MΔC. We observe transient structures with partial structural features from both the active and inactive states in c-Src3MΔC. Together with our results on their unfolding cooperativity, this indicates that there exist more metastable structures in v-Src, which could be stabilized by the interaction with Hsp90. Thermodynamically, an increased population of different native-like structures would be expected to result in an entropic gain, which render the activation process more efficient. A general increase in conformational flexibility corroborates previous studies suggesting a correlation between chaperone binding and the openness of the kinase fold (59).

Although the β4- and β5-strands in the kinase domain have previously been suggested to be important for chaperone–kinase interaction (55), the exposure of the β1-, β2-, and β3-strands in v-Src shown here has not yet been correlated with chaperone recognition.

For the ErbB2 kinase domain, it was found that introducing a negative charge in the αC-β4–loop strongly decreased its Hsp90 dependence (60). Interestingly, in the case of v-Src, the increased Hsp90 dependence cannot be explained by increased hydrophobicity of this region as the R318Q mutation and the presence of other hydrophilic residues in v-Src leaves the αC-β4–loop polar. This implies that Hsp90 does not generally interact with a hydrophobic αC-β4–loop, but rather with a kinase that shows more flexibility in this region. In addition, the finding that mutated ErbB2 remained Hsp90-dependent during its initial folding (60) is in line with our suggestion that Hsp90 and Cdc37 may recognize more exposed “epitopes” in client kinases.

Previous screens found that determinants of the mature kinase–chaperone interaction are distributed over both lobes of the kinase domain and correlated kinase stability with Hsp90 dependence (5), supporting an early study on the stability of c-Src and v-Src (38). Here, we extend the picture and show that Hsp90 dependence directly correlates with unfolding cooperativity, tryptophan accessibility, and hydrophobicity, and furthermore with the extent of exposure of structural elements in the kinase domain.

Given the high similarities between chaperone-dependent and -independent kinases, the idea has been raised that client kinases would frequently expose Hsp90 binding sites, whereas stable kinases only do so during initial folding and therefore only transiently interact with chaperones during maturation (38, 61). Our results are in line with this suggestion as they show that the degree of exposition of these sites correlates with the strength of the dependence on Hsp90, increasing from c-Src, over c-Src3M, to v-Src. Furthermore, we find that the C-terminal tail deletion strongly increases the accessibility of the distant active center and the A-loop.

These results support the notion that v-Src may exist in multiple native-like states. We suggest that the activated state of the kinase is instable and reverts to the less active state unless Hsp90 is present, which may induce or select this state. This, in effect, leads to an apparent higher activity of v-Src in the presence of Hsp90.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and Expression of c-Src, v-Src, and Src Mutants in Sf9 Cells.

Chicken c-Src and v-Src from Rous sarcoma virus (Schmidt-Ruppin strain A) were used in this study. Coding genes were obtained by PCR using 5′-CATCGCCCATGGCCGGGAGCAGCAAGAGCAAGC-3′ (containing a NcoI restriction site) as forward primer and 5′-CACATAAGCTTTCACTATAGGTTCTCTCCAGGCTG-3′ and 5′-CACATAAGCTTCTACTCAGCGACCTCCAACACACAA-3′ (both containing a HindIII restriction site) as reverse primers for c-Src and v-Src, respectively. For the C-terminal truncation mutants of c-Src, 5′-GATCAAGCTTCTACAGGAAGGCCTGCAGGTACTCAAAAGTC-3′ (containing a HindIII restriction site) was used as reverse primer. Templates of Src were generated as described elsewhere (38). Point mutants of all genes were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. After amplification, the Src variants were cloned into the pFastBacHTA expression plasmid (Invitrogen) and subsequently transformed into DH10Bac Escherichia coli cells (Invitrogen) for producing recombinant Bacmid DNA. For generating recombinant baculovirus, Sf9 cells in monolayer culture were transfected with 1 µg of Bacmid-DNA at a density of 9 × 105 cells per well and incubated a further 7–10 d. For expression, 20 µL of virus per mL were added to 2 × 106 cells per mL in suspension culture and incubated for 48 h at 27 °C.

Protein Purification.

For purification of Src kinases, Sf9 cells resuspended in immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) buffer [40 mM Tris⋅HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerine, pH 7.5] containing a protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma) were sonicated on ice and centrifuged (20,000 × g, 40 min, 4 °C). The cleared lysate was loaded onto a Cobalt-Talon column (BD Biosciences) preequilibrated in IMAC buffer. To remove unspecifically bound proteins, the column was washed with IMAC buffer and subsequently with IMAC buffer containing 15 mM imidazole. The kinase was eluted with IMAC buffer containing 300 mM imidazole. Src kinase containing fractions were pooled, concentrated to 5 mL, loaded onto a Superdex 75 16/60-pg column (GE Healthcare) for size exclusion chromatography, and eluted with IMAC buffer containing 5 mM DTT (Src buffer).

Human Hsp90α and Hsp90β wild-type and mutants were expressed in the E. coli strain BL21 as a His6-tagged version using a pET28 vector. Human Cdc37 wild-type and Cdc37 mutants were expressed in the E. coli strain HB101 as a His6-tagged version using a pQE30 vector containing the respective gene. Hsp90, Cdc37, Hop, Hdj1, and Hsp70 were expressed and purified as described (62–64).

Kinase Activity Assay.

For activity measurements of Src variants, 320 nM of the respective kinase variant was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min in Src buffer supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, and 40 µM [γ-32P]ATP with an activity of 0.5 µCi. A 10-fold molar excess (3.2 µM) of acid-denatured enolase (Sigma) was used as a substrate. For that enolase was incubated with 25 µM acetic acid (pH 3.0) for 5 min at 30 °C and subsequently neutralized by adding 200 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The kinase reaction was stopped by adding Laemmli buffer and boiling the sample. The samples were separated by SDS/PAGE, and transphosphorylation was detected by applying a phosphor image screen onto the gel. The screen was analyzed using a Typhoon 9200 PhosphorImager and the program ImageQuant (GE Healthcare). The kinase reaction was performed either in the absence or presence of different amounts of chaperones.

Temperature Dependence of Kinase Activation and Stabilization.

To investigate the influence of the temperature on the activity of Src variants and the influence of chaperones on this process, the kinases were first preincubated on ice in the presence or absence of chaperones in Src buffer with 5 mM MgCl2 for 10 min, and subsequently incubated at increasing temperatures for 10 min and cooled down on ice for 10 min. Then enolase and [γ-32P]ATP were added, and the activity was measured as described above.

CD Spectroscopy: Thermal Transition.

The thermal unfolding of the proteins was monitored at 222 nm in 30 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 30 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, pH 7.5, using a 0.1-cm quartz cuvette and a protein concentration of 100 µg/mL by measuring changes of the CD signal between 20 and 80 °C, at a heating rate of 20 °C per h. The curves were fitted to a sigmoidal transition.

Aggregation Assay.

The 1.6 µM kinase was incubated at 45 °C for 10 min. To remove insoluble aggregates, the proteins were subsequently centrifuged for 60 min (20,000 × g; 4 °C). Pellet and supernatant proteins were denatured in Laemmli buffer, boiled at 95 °C, and subsequently analyzed by SDS/PAGE and densitometry.

Yeast Viability Assay.

The Hsp90 double-knockout strain ECU82α containing yeast Hsp82 on a plasmid (yHsp82 in pRS426) was transformed with plasmids containing the Src variants under a galactose promoter (Src in pY413). After growing in glucose-containing URA/LEU/HIS selection medium to stationary phase, cells were diluted in a 10-fold dilution series and 3 µL of each dilution were spotted on agar plates containing galactose as sole sugar source. Cells were grown at 30 °C for 3 d. In a second approach, the Hsp90 inhibitor Radicicol was added at a final concentration of 5 µM to the plates for determining the Hsp90 dependence of the expressed Src variants.

Western Blotting.

Src-plasmid–transformed yeast cells were grown at 30 °C in raffinose-containing URA/LEU/HIS selection medium to stationary phase, spun down, and resuspended in glucose-free URA/LEU/HIS medium containing galactose for induction of Src expression. The cells were grown for 6 h at 30 °C and spun down, and the pellet resuspended in 250 µL of extraction buffer [8 M urea, 5% (wt/vol) SDS, 40 mM Tris, 0.1 M EDTA, pH 7.5] and additionally lysed with glass beads. After centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 5 min, the protein concentration of the supernatant was measured using a Nanodrop (Peqlab) and normalized. After SDS buffer addition and incubation at 95 °C for 5 min, a 10% SDS/PAGE was run for Western blotting. The blotted membrane was blocked with 5% (wt/vol) milk in TBS-T (0.1% Tween 20) for 30 min and subsequently treated with mouse anti-phosphotyrosine antibody clone 4G10 (1:1,000 in TBS-T, 1% milk) (Merck Millipore). After three 10-min washing steps with TBS-T, the membrane was treated with the secondary rabbit peroxidase (POD)-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (1:10,000 in TBS-T, 1% milk) (Sigma). The blot was washed with TBS-T, POD reaction was performed using ECLplus Western Detection System (GE Healthcare), and the chemiluminescence was visualized by exposing the blot to Kodak X-Omat.

For detection of Src kinase in the yeast lysates, after blocking with 3% (wt/vol) milk in PBS-T (0.1% Tween 20) for 30 min the membrane was treated with mouse anti-avian Src antibody clone EC10 (1:1,000 in PBS-T, 1% milk) (Merck Millipore). After washing in PBS-T, the membrane was treated with the secondary rabbit POD-conjugated anti-mouse antibody and developed as described.

ANS Binding Assay.

A concentration of 1.6 µM of the respective kinase variant was incubated with 30 µM ANS (Sigma) in Src buffer for 20 min at room temperature and subsequently analyzed in a FluoroMax-3 fluorescence spectrometer (Spex) with an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 470 nm. The obtained emission spectra of the proteins were normalized against the Src buffer blank.

Tryptophan Quenching.

Five molar acrylamide was titrated to a 500 nM Src kinase in Src buffer at 25 °C. Tryptophan fluorescence emission quenching upon excitation at 295 nm was recorded using a FluoroMax-3 fluorescence spectrometer (Spex). The slit widths were set to 3 and 5 nm for excitation and emission, respectively. The changes in fluorescence intensity were plotted against the acrylamide concentration according to a modified Stern–Volmer equation (42):

| [1] |

where F0 is the total fluorescence in the absence of quencher, ΔF is the fluorescence intensity change at a given quencher concentration [Q], fa is the accessible tryptophan fraction, and Ka is the Stern–Volmer quenching constant of the accessible fraction (38).

Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange–Mass Spectrometry.

Hydrogen/deuterium exchange–mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) experiments were performed on a fully automated system equipped with a Leap robot (HTS PAL; Leap Technologies), a Waters ACQUITY UPLC, a HDX manager, and the Synapt G2-S mass spectrometer as described elsewhere (Waters) (65). Src kinases were vacuum concentrated in the presence of 100 mM trehalose (Sigma). The protein samples were diluted in a ratio of 1:4 with deuterium oxide-containing Src buffer [40 mM Tris, pH 7.1, 150 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerine, 5 mM DTT] and incubated at 25 °C for 20, 60, 600, 3,600, and 7,200 s. After the labeling reaction, the protein was denatured and the exchange was stopped by diluting the labeled protein 1:1 in quenching buffer [50 mM Na2HPO4 × 2 H2O, 50 mM NaH2PO4 × 2 H2O; 35 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 4 M Gua-HCl, pH 2.6, 4 °C]. Digestion was performed on-line by an immobilized pepsin column (Applied Biosystems, Poroszyme). Peptides were trapped and subsequently separated on a Waters UPLC CSH C 18 column (1.7 µm, 1.0 × 100 mm) with a H2O plus 0.1% formic acid (vol/vol) and ACN plus 0.1% formic acid (vol/vol) gradient. Trapping and chromatographic separation were carried out at 0 °C to minimize back-exchange. Eluting peptides were directly subjected to the time-of-flight mass spectrometer by electrospray ionization. Before fragmentation by MSE and mass detection in resolution mode, the peptide ions were additionally separated by drift time within the mobility cell. Data processing was performed using the Waters Protein Lynx Global Server PLGS (Version 2.5.3) and DynamX (Version 2.0).

Molecular Dynamics Simulations.

The structure of wild-type c-Src [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID 1Y57] (66) was obtained from Brookhaven Databank and used for constructing the c-Src3MΔC variant by introducing point mutations (R95W, D117Q, R318Q) in silico and by removing the C-terminal tail (ΔC). The models were solvated in a water box using a 100 mM sodium chloride concentration. The systems were simulated for 250 ns with a 2-fs integration time step at T = 310 K, and by using the CHARMM27 force field (67). The simulations were performed using NAMD (68), and Visual Molecular Dynamics (69) was used for analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Neckers for kindly providing Hsp90β-E42A and Hsp90β-D88A plasmids, A. Liebscher for excellent practical assistance, O. Lorenz for providing purified Hop, P. Sahasrabudhe for supporting yeast experiments, and all members of the J.B. laboratory for discussions. We acknowledge the high-performance Biowulf cluster (biowulf.nih.gov) at the National Institutes of Health for providing computational resources. V.R.I.K. acknowledges the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation for financial support. The project was funded by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB1035) (to J.B.). E.E.B. acknowledges a PhD scholarship from the Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1424342112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Röhl A, Rohrberg J, Buchner J. The chaperone Hsp90: Changing partners for demanding clients. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38(5):253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taipale M, Jarosz DF, Lindquist S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: Emerging mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(7):515–528. doi: 10.1038/nrm2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picard D. Heat-shock protein 90, a chaperone for folding and regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59(10):1640–1648. doi: 10.1007/PL00012491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClellan AJ, et al. Diverse cellular functions of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone uncovered using systems approaches. Cell. 2007;131(1):121–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taipale M, et al. Quantitative analysis of HSP90-client interactions reveals principles of substrate recognition. Cell. 2012;150(5):987–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandal AK, et al. Cdc37 has distinct roles in protein kinase quality control that protect nascent chains from degradation and promote posttranslational maturation. J Cell Biol. 2007;176(3):319–328. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenz OR, et al. Modulation of the Hsp90 chaperone cycle by a stringent client protein. Mol Cell. 2014;53(6):941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karagöz GE, et al. Hsp90-Tau complex reveals molecular basis for specificity in chaperone action. Cell. 2014;156(5):963–974. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali MM, et al. Crystal structure of an Hsp90-nucleotide-p23/Sba1 closed chaperone complex. Nature. 2006;440(7087):1013–1017. doi: 10.1038/nature04716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hessling M, Richter K, Buchner J. Dissection of the ATP-induced conformational cycle of the molecular chaperone Hsp90. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(3):287–293. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiau AK, Harris SF, Southworth DR, Agard DA. Structural analysis of E. coli hsp90 reveals dramatic nucleotide-dependent conformational rearrangements. Cell. 2006;127(2):329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graf C, Stankiewicz M, Kramer G, Mayer MP. Spatially and kinetically resolved changes in the conformational dynamics of the Hsp90 chaperone machine. EMBO J. 2009;28(5):602–613. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishra P, Bolon DN. Designed Hsp90 heterodimers reveal an asymmetric ATPase-driven mechanism in vivo. Mol Cell. 2014;53(2):344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richter K, et al. Conserved conformational changes in the ATPase cycle of human Hsp90. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):17757–17765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Buchner J. Structure, function and regulation of the hsp90 machinery. Biom J. 2013;36(3):106–117. doi: 10.4103/2319-4170.113230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dey B, Lightbody JJ, Boschelli F. CDC37 is required for p60v-src activity in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7(9):1405–1417. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.9.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stepanova L, Leng X, Parker SB, Harper JW. Mammalian p50Cdc37 is a protein kinase-targeting subunit of Hsp90 that binds and stabilizes Cdk4. Genes Dev. 1996;10(12):1491–1502. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.12.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandhakavi S, McCann RO, Hanna DE, Glover CV. A positive feedback loop between protein kinase CKII and Cdc37 promotes the activity of multiple protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(5):2829–2836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shao J, Prince T, Hartson SD, Matts RL. Phosphorylation of serine 13 is required for the proper function of the Hsp90 co-chaperone, Cdc37. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(40):38117–38120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300330200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siligardi G, et al. Regulation of Hsp90 ATPase activity by the co-chaperone Cdc37p/p50cdc37. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(23):20151–20159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu Y, Lindquist S. Heat-shock protein hsp90 governs the activity of pp60v-src kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(15):7074–7078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogt PK. Retroviral oncogenes: A historical primer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(9):639–648. doi: 10.1038/nrc3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stehelin D, Varmus HE, Bishop JM, Vogt PK. DNA related to the transforming gene(s) of avian sarcoma viruses is present in normal avian DNA. Nature. 1976;260(5547):170–173. doi: 10.1038/260170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Y, Singer MA, Lindquist S. Maturation of the tyrosine kinase c-src as a kinase and as a substrate depends on the molecular chaperone Hsp90. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(1):109–114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper JA, Gould KL, Cartwright CA, Hunter T. Tyr527 is phosphorylated in pp60c-src: Implications for regulation. Science. 1986;231(4744):1431–1434. doi: 10.1126/science.2420005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds AB, et al. Activation of the oncogenic potential of the avian cellular src protein by specific structural alteration of the carboxy terminus. EMBO J. 1987;6(8):2359–2364. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnier JV, Dezélée P, Marx M, Calothy G. Nucleotide sequence of the src gene of the Schmidt-Ruppin strain of Rous sarcoma virus type E. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17(3):1252. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.3.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Czernilofsky AP, et al. Nucleotide sequence of an avian sarcoma virus oncogene (src) and proposed amino acid sequence for gene product. Nature. 1980;287(5779):198–203. doi: 10.1038/287198a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy S, Mazzu D, Mahan D, Shalloway D. Sequence and functional differences between Schmidt-Ruppin D and Schmidt-Ruppin A strains of pp60v-src. J Virol. 1990;64(7):3545–3550. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3545-3550.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeya T, Hanafusa H. Structure and sequence of the cellular gene homologous to the RSV src gene and the mechanism for generating the transforming virus. Cell. 1983;32(3):881–890. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iba H, Takeya T, Cross FR, Hanafusa T, Hanafusa H. Rous sarcoma virus variants that carry the cellular src gene instead of the viral src gene cannot transform chicken embryo fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81(14):4424–4428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato JY, et al. Amino acid substitutions sufficient to convert the nontransforming p60c-src protein to a transforming protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6(12):4155–4160. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyazaki K, et al. Critical amino acid substitutions in the Src SH3 domain that convert c-Src to be oncogenic. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;263(3):759–764. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nathan DF, Lindquist S. Mutational analysis of Hsp90 function: Interactions with a steroid receptor and a protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(7):3917–3925. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brugge JS. Interaction of the Rous sarcoma virus protein pp60src with the cellular proteins pp50 and pp90. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1986;123:1–22. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-70810-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaughan CK, et al. Hsp90-dependent activation of protein kinases is regulated by chaperone-targeted dephosphorylation of Cdc37. Mol Cell. 2008;31(6):886–895. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith JR, et al. Restricting direct interaction of CDC37 with HSP90 does not compromise chaperoning of client proteins. Oncogene. 2015;34(1):15–26. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Falsone SF, Leptihn S, Osterauer A, Haslbeck M, Buchner J. Oncogenic mutations reduce the stability of SRC kinase. J Mol Biol. 2004;344(1):281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obermann WM, Sondermann H, Russo AA, Pavletich NP, Hartl FU. In vivo function of Hsp90 is dependent on ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143(4):901–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Panaretou B, et al. ATP binding and hydrolysis are essential to the function of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone in vivo. EMBO J. 1998;17(16):4829–4836. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyn MA, 3rd, Schreiner SJ, Dumitrescu TP, Nau GJ, Smithgall TE. SRC family kinase activity is required for murine embryonic stem cell growth and differentiation. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68(5):1320–1330. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.010231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lakowicz JR, ed (1999) Principles in Fluorescence Spectroscopy (Plenum Press, New York), p 724. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snyder MA, Bishop JM, McGrath JP, Levinson AD. A mutation at the ATP-binding site of pp60v-src abolishes kinase activity, transformation, and tumorigenicity. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5(7):1772–1779. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.7.1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ozkirimli E, Yadav SS, Miller WT, Post CB. An electrostatic network and long-range regulation of Src kinases. Protein Sci. 2008;17(11):1871–1880. doi: 10.1110/ps.037457.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozkirimli E, Post CB. Src kinase activation: A switched electrostatic network. Protein Sci. 2006;15(5):1051–1062. doi: 10.1110/ps.051999206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shukla D, Meng Y, Roux B, Pande VS. Activation pathway of Src kinase reveals intermediate states as targets for drug design. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3397. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghaemmaghami S, et al. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425(6959):737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jorgensen P, Nishikawa JL, Breitkreutz BJ, Tyers M. Systematic identification of pathways that couple cell growth and division in yeast. Science. 2002;297(5580):395–400. doi: 10.1126/science.1070850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwarze SR, Fu VX, Jarrard DF. Cdc37 enhances proliferation and is necessary for normal human prostate epithelial cell survival. Cancer Res. 2003;63(15):4614–4619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Polier S, et al. ATP-competitive inhibitors block protein kinase recruitment to the Hsp90-Cdc37 system. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9(5):307–312. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eustace BK, et al. Functional proteomic screens reveal an essential extracellular role for hsp90 alpha in cancer cell invasiveness. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(6):507–514. doi: 10.1038/ncb1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gasch AP, et al. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(12):4241–4257. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson JL, Brown C. Plasticity of the Hsp90 chaperone machine in divergent eukaryotic organisms. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;14(1):83–94. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0058-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frame MC. Src in cancer: Deregulation and consequences for cell behaviour. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1602(2):114–130. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prince T, Matts RL. Definition of protein kinase sequence motifs that trigger high affinity binding of Hsp90 and Cdc37. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(38):39975–39981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prince T, Sun L, Matts RL. Cdk2: A genuine protein kinase client of Hsp90 and Cdc37. Biochemistry. 2005;44(46):15287–15295. doi: 10.1021/bi051423m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Citri A, et al. Hsp90 recognizes a common surface on client kinases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(20):14361–14369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miyata Y. Protein kinase CK2 in health and disease: CK2: The kinase controlling the Hsp90 chaperone machinery. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(11-12):1840–1849. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-9152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grbovic OM, et al. V600E B-Raf requires the Hsp90 chaperone for stability and is degraded in response to Hsp90 inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(1):57–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609973103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu W, et al. Surface charge and hydrophobicity determine ErbB2 binding to the Hsp90 chaperone complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12(2):120–126. doi: 10.1038/nsmb885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caplan AJ, Mandal AK, Theodoraki MA. Molecular chaperones and protein kinase quality control. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(2):87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eckl JM, et al. Cdc37 (cell division cycle 37) restricts Hsp90 (heat shock protein 90) motility by interaction with N-terminal and middle domain binding sites. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(22):16032–16042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.439257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bose S, Weikl T, Bügl H, Buchner J. Chaperone function of Hsp90-associated proteins. Science. 1996;274(5293):1715–1717. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peschek J, et al. Regulated structural transitions unleash the chaperone activity of αB-crystallin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(40):E3780–E3789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308898110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang A, et al. Understanding the conformational impact of chemical modifications on monoclonal antibodies with diverse sequence variation using hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry and structural modeling. Anal Chem. 2014;86(7):3468–3475. doi: 10.1021/ac404130a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cowan-Jacob SW, et al. (2005) The crystal structure of a c-Src complex in an active conformation suggests possible steps in c-Src activation. Structure 13:861–871. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.MacKerell AD, Jr, et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102(18):3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Phillips JC, et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26(16):1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14(1):33–38, 27–28. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.