Abstract

Research on pregnancy termination (PT) largely assumes HIV status is the only reason why HIV-positive women contemplate abortion. As antiretroviral treatment (ART) becomes increasingly available and women are living longer, healthier lives, the time has come to consider the influence of other factors on HIV-positive women’s reproductive decision-making. Because ART has been free and universally available to Brazilians for more than two decades, Brazil provides a unique context in which to explore these issues. Twenty-five semi-structured interviews exploring women’s PT decision-making were conducted with women receiving care at the Reference Centre for HIV/AIDS in Salvador, Brazil. Interviews were transcribed, translated into English, and coded for analysis. HIV played different roles in women’s decision-making. 13 HIV-positive women did not consider PT. Influential factors described by those who did consider PT included fear of HIV transmission, fear of HIV-related stigma, family size, economic constraints, partner and provider influence, as well as lack of access to such services as PT and abortifacients. For some HIV-positive women in Brazil, HIV can be the only reason to consider PT, but other factors are significant. A thorough understanding of all variables affecting reproductive decision-making is necessary for enhancing services and policies and better meeting the needs and rights of HIV-positive women.

Keywords: pregnancy termination, abortion, HIV/AIDS, Brazil

Introduction

The advent and increased accessibility of antiretroviral treatment (ART) has significantly impacted on HIV-positive women’s and men’s decisions regarding conception, pregnancy continuation and elective pregnancy termination (PT). (Boonstra 2006; MacCarthy et al. 2012) With access to ART prophylaxis and treatment, HIV-positive women who wish to become pregnant can undergo labour, delivery and breastfeeding with greatly reduced risk of vertical HIV transmission.(Mazzeo et al. 2012) Some researchers, programmers and policymakers historically assumed that HIV-positive women would (or should) attempt to avoid pregnancy altogether or terminate pregnancies solely on the basis of their HIV-positive status. Although global or regional epidemiological data on abortion is not commonly disaggregated by HIV status (World Health Organization 2011), studies focused on HIV-positive women in Vietnam (Bui et al. 2010), South Africa (Cooper et al. 2007), the USA (Massad et al. 2004; Blair et al. 2004) and several European countries (van Benthem et al. 2000; Bongain et al. 2002; Greco et al. 1999) documented a substantial decrease in the rate of PT following the availability of ART.

The World Health Organization (WHO) established in 2006 that both surgical and medication (or “medical”) abortions are safe for HIV-positive women when performed under certain conditions. (World Health Organization and United Nations Population Fund 2006) Still, access to abortion services for HIV-positive women remains either limited or altogether absent in many countries across the globe.(Boonstra 2006; World Health Organization and United Nations Population Fund 2006) While HIV-positive and HIV-negative women experience limited access to safe abortion procedures globally, the consequences of unsafe abortion may be more severe for women living with HIV than their HIV-negative counterparts given their heightened risk for infection, sepsis and haemorrhage. (de Bruyn 2003; Delvaux and Nostlinger 2007)

In Brazil, where ART has been free and universally available for almost 20 years, HIV status may be an important factor in women’s decisions to continue or terminate a pregnancy. (Barbosa et al. 2012) Despite Brazil’s progressive national response to HIV, however, the links between pregnancy termination and persistently high maternal mortality – which has not improved in 15 years – have not been addressed by public health policies. (Diniz 2007) The Brazilian penal code has limited access to legal abortion services for Brazilian women since 1940, and abortion-related health complications accounted for 11.4% of maternal mortality in 2004 (not disaggregated by HIV status). (Laurenti, Mello Jorge, and Gotlieb 2004) In 2012, the Supreme Court of Brazil ruled that a woman is exempt from criminal penalities for seeking an abortion only when her life is in danger, when pregnancy results from rape, or when the foetus has severe genetic abnormalities.(Human Rights Watch 2012) Women wishing to terminate a pregnancy for any other reason must seek services outside the formal health system, potentially resulting in unsafe procedures. (Goldman et al. 2005) Furthermore , hospitals require court rulings to proceed with pregnancy terminations, and the ensuing legal process often delays abortion beyond the first or second trimester. Some women additionally avoid seeking post-abortion care for fear of arrest or imprisonment. (Menezes and Aquino 2009)

Research conducted in Brazil has the potential to provide unique insight into the determinants of reproductive decision-making among HIV-positive women in the context of universal access to ART. To date, the impact of HIV on abortion in Brazil is unclear: initial evidence from data collected in 2003 and 2004 suggested that after controlling for several factors, there were not statistically significant differences between the rates of abortion among HIV-positive women and HIV-negative women. (Barbosa et al. 2009; Santos NJS, Barbosa RM, and Pinho AA 2009) These studies, however, did not explore the reasons informing why women sought to terminate their pregnancy. Two recent studies based on data from 2009 and 2010 revealed that a myriad of determinants are shared across HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. (Barbosa et al. 2012; Villela et al. 2012) To better inform the ways in which services and policies can meet the sexual and reproductive needs and rights of HIV-positive women in Brazil and more globally, we conducted a qualitative study to further explore the role of HIV in reproductive-decision making among 25 HIV-positive women in Salvador, the third most populous and one of the poorest cities in Brazil. (Instituto Brasiliero de Geografia e Estatistica 2005)

Methods

Qualitative data were collected in semi-structured interviews with 25 HIV-positive women who knew their HIV status, currently or previously had planned or unplanned pregnancies, and who were receiving HIV-related care at the only State Reference Centre (SRC) for HIV/AIDS in Salvador, Brazil. All interviewers received training related to HIV and AIDS, and interview scripts were extensively field-tested. Researchers (SM and ID) met weekly with study staff to review pilot interviews, ensuring clarity of questions asked and quality of information collected.

Employing a convenience sampling strategy, women with scheduled appointments at the SRC were approached by the interviewers. Women who gave informed consent to participate were interviewed in a private room. All interviews were conducted individually and recorded. They were later transcribed and professionally translated from Portuguese into English for analysis.

Transcripts and related field notes were evaluated, and researchers identified deductive codes following a review of the literature. Next, inductive codes were used to identify new factors in the transcripts that may not have been highlighted by the existing literature. As categories emerged, data was pulled from relevant categories and compared. The relationships among categories were specified and outliers were explored. Finally, exemplars were identified to further illuminate the key themes emerging from each interview. Data was reviewed and discussed by three authors (SM, JR and ACR), and conclusions were reviewed by an additional author (ID) to ensure consistency with the Brazilian cultural context.

Results

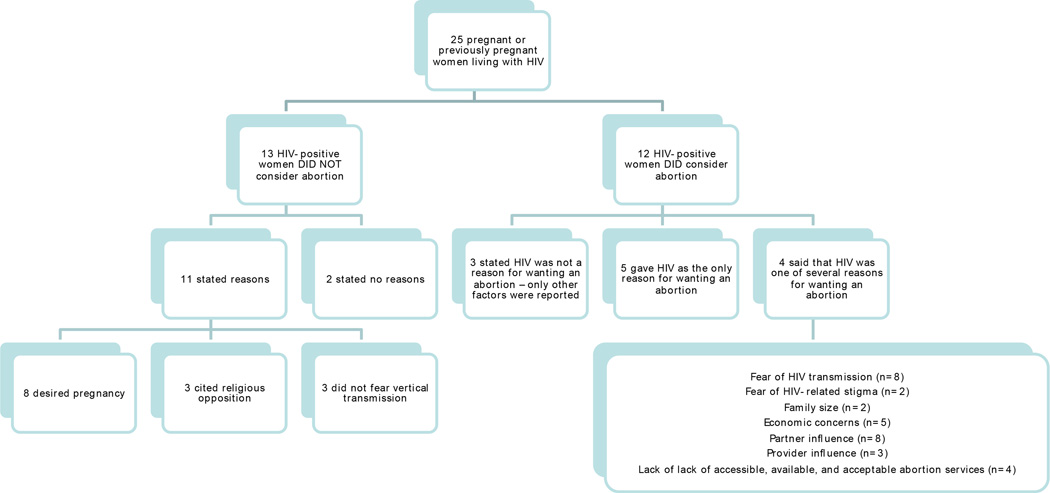

Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics of study participants. The results, detailed in Figure A, demonstrate that a continuum of experiences exists between women who did not (n=13) and those who did (n=12) consider PT.

Table 1.

Description of the demographic characteristics among women receiving HIV/AIDS care at the State Reference Center in Salvador, Brazil (n=25)

| VARIABLES | n |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Less than 24 years | 5 |

| 25 – 34 years | 13 |

| 35 and older | 7 |

| Color / Ethnicity* | |

| Brown | 11 |

| Black | 11 |

| Other | 3 |

| Civil status | |

| Married or live with someone | 14 |

| Single or divorced | 11 |

| Number of children | |

| 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 8 |

| 3 or more | 3 |

| 4 | |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 19 |

| Employed (formally or informally) | 6 |

| Monthly income of those working** | |

| Minimum wage or below | 4 |

| Above minimum wage | 2 |

| Length of time since diagnosis with HIV | |

| Less than 1 year | 12 |

| Between 1 and 2 years | 5 |

| 3 or more years | 8 |

| On treatment for HIV at the time of interview | |

| Yes | 13 |

| No | 12 |

Race is commonly referred to as cor or ‘color,’ and references the phenotype (physical appearance) and not one’s ancestry (origin).

Minimum wage of $510 BR per month = $328.11 USD per month as established by the Brazilian government

Figure A.

Summary of Results from semi-structured interviews with 25 currently or previously pregnant women who were receiving HIV/AIDS care at the only Reference Centre for HIV/AIDS in Salvador, Brazil.

*Many participants cited several reasons, reasons are thus non-exclusive within categories

HIV-positive women who did not consider abortion

Approximately half of respondents never considered abortion as an outcome for their pregnancies (n=13). While two women did not explain their rationale for not considering abortion, eight women stated that the pregnancy was desired, even if unplanned. Three objected to abortion on religious grounds: As Sandra, age 35, explained: “… I saw what I would be doing [if I had an abortion]…practicing a sin…I would not have salvation!” Of those women who did not consider terminating their pregnancies, three explained that they did not fear vertical transmission, especially after they gained knowledge about strategies to reduce the risk of HIV transmission. HIV-related concerns were otherwise not significantly related to these women’s wishes to continue their pregnancies.

HIV-positive women who did consider abortion – the role of HIV

Of the 12 women who did consider terminating their pregnancies, three women stated that their positive HIV status did not affect their desire to terminate their pregnancies. In contrast, five women contemplated this option solely on the basis of HIV-related concerns, particularly out of fear of vertical transmission during pregnancy or childbirth. Andrea, age 23, stated: “[My biggest worry] was of the child being infected…So much so that I even thought about [terminating the pregnancy].” In addition to their fear of vertical transmission, other HIV-related concerns included the potential stigma an HIV-positive child would endure during its life. Again Sandra explained: “I thought it would be just another child to suffer prejudice. Because people are prejudiced!”

HIV-positive women who did consider abortion – the role of other factors

Four women considered abortion because of the aforementioned HIV-related concerns in addition to other factors, such as desired family size; economic status; partner influence; provider influence; and the lack of affordable, accessible, and available abortion services. Many of these determinants were also considerations for HIV-positive women who did not consider abortion, serving as rationale to continue a pregnancy for some women while leading other women to consider abortion.

Desired family size was a significant concern for two HIV-positive women, influencing one participant to consider abortion because she was satisfied with her family size while encouraging another to continue her pregnancy because her desire to have more children outweighed fears of HIV transmission.

Economic worries affected the decision-making of five women: Many interviewees struggled to provide for current children and expressed concern over meeting the financial needs of another child. As Maria, age 31, remarked, “I already have a hard time taking care of this one, imagine another one.”

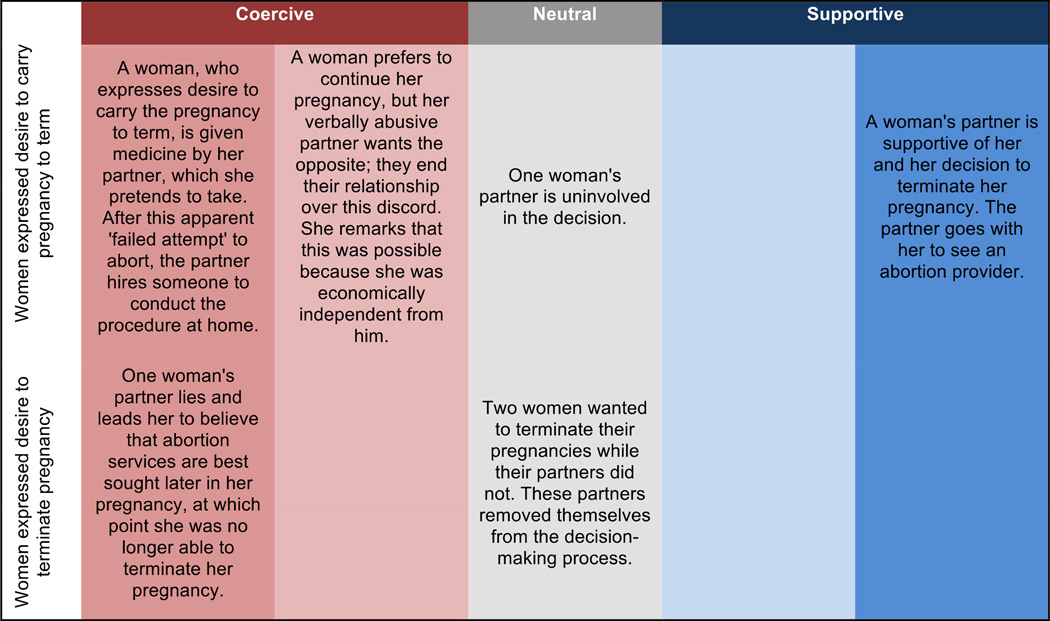

Partners’ preferences and behaviours played an important role in many women’s decisions around abortion (n=8). Like women’s preferences, partners’ personal preferences regarding abortion varied: some partners were personally in favour of abortion, while others opposed it. Of note, the ways in which partners expressed their personal opinions and desires for continuing or terminating the pregnancy ranged from supportive to coercive, along a spectrum (see Figure B).

Figure B.

The ways in which partners expressed their personal opinions and desires for continuing or terminating a pregnancy ranged from supportive to coercive.

While some partners were uninvolved or apathetic, some actively supported women in their decision (either to continue or terminate the pregnancy). Other partners, however, forcefully expressed their opinions about the pregnancy outcome, misleading or even coercing female participants into either having an abortion or continuing their pregnancy. For instance, when asked about her pregnancy, Sandra replied:

“I did not [want the pregnancy]. I wanted to take it out, I wanted to abort. And [my partner] promised me: ‘Let’s wait two months because it's easier to get the baby out.’ Except he was lying to me…everyone knows that when you wait for two full months it is already a risk to end the pregnancy…he always wanted this pregnancy.”

The status or stability of a woman’s relationship with her partner also influenced her reproductive decision-making. One woman‘s desire to continue her pregnancy was explicitly motivated by the possibility that having a child with her partner would strengthen their relationship. In contrast, another respondent considered terminating her pregnancy because the child was not her partner’s. Women additionally referenced their partners’ involvement and responsibility, or lack thereof, when weighing their decision to continue or terminate a pregnancy.

Service providers influenced the pregnancy decision-making of three women. In this study, health care providers uniformly encouraged women to continue their pregnancies. Providers not only informed pregnant HIV-positive women about methods to prevent vertical transmission but in some cases actively discouraged abortion. One health provider, for example, reportedly counselled an HIV-positive woman not to “think about any stupidity,” by which he meant abortion:

Patricia (age 35): “[The doctor] said, ‘Bring [the pregnancy test] to me as soon as you get the result…don’t you think about any stupidity, no…you, like any other woman, can have a baby… It cannot be a natural birth. It has to be a C-Section…you cannot breastfeed, but there is the milk’. He then kept [saying to] me: ‘Don’t you think about any stupidity, nothing.”

The lack of available, acceptable and accessible abortion services also affected women’s pregnancy decisions (n=4). One woman who otherwise favoured abortion decided against termination out of fear of acquiring a bacterial infection during the procedure. Three participants who decided to terminate their pregnancy sought abortion services but were subsequently unable to access services or the pharmaceuticals to terminate their pregnancies. One woman described trying “Twice…I made some tea…I [drank the] tea and…I did everything but could not [abort].”

Discussion

Approximately half of the women included in this study did not consider abortion upon learning they were pregnant. These women expressed a desire to carry their pregnancies to term and cited religious beliefs and/or lack of concern for vertical transmission as reasons to continue their pregnancies. These responses, which have been documented in Brazil and other settings (Chi et al. 2010; Cooper et al. 2007; Ingram and Hutchinson 2000; Hebling and Hardy 2007), may reflect the relative social value placed on children and motherhood. The decision to continue a pregnancy by women who were unconcerned about vertical transmission more likely reflects the impact of information and counselling on preventing vertical transmission that women received rather than any lesser or lack of concern for the health of their infants. (MacCarthy et al. 2013)

Women who did not consider abortion either explicitly noted that their decisions were not motivated by HIV or did not mention HIV as influencing their choices. These results also corroborate prior research (Smits et al. 1999; Johnstone et al. 1990; Kline, Strickler, and Kempf 1995; Orner, de Bruyn, and Cooper 2011; Barbosa et al. 2009), suggesting that, among women who wish to continue a pregnancy, HIV-related concerns are minimal compared to desires for children and/or religious stances against abortion.

On the other hand, HIV was either the only reason or one of several reasons that three quarters of women contemplated abortion. HIV and the risk of vertical transmission to their infants and/or fear of the subsequent stigma experienced by HIV-positive infants were significant concerns, but other women were motivated to consider abortion because of other factors in constellation with these HIV-related concerns. This finding corroborates other studies that have documented HIV/AIDS as a prominent or primary motivation for considering abortion,(Craft et al. 2007; Lindgren et al. 1998; Bui et al. 2010; Bedimo, Bessinger, and Kissinger 1998) or as one of several influences.(Cooper et al. 2007; Kirshenbaum et al. 2004; Orner et al. 2010; Kanniappan, Jeyapaul, and Kalyanwala 2008; Floridia et al. 2010)

A perceived inability to meet the financial needs of a child as well as women’s partners’ preferences were major considerations for HIV-positive women weighing up whether to continue or terminate a pregnancy. Other studies have documented that economically dependent women are more likely to be influenced by family and partner preferences.(Bedimo, Bessinger, and Kissinger 1998; Kanniappan, Jeyapaul, and Kalyanwala 2008; Chi et al. 2011; Lindgren et al. 1998; Orner et al. 2010; Orner et al. 2011; Villela et al. 2012; de Bruyn 2004, 2006)

Among HIV-positive women that did not consider abortion as well as women who did, partner and health provider preferences were important determinants of pregnancy intentions. As depicted in Figure B, regardless of their actual preference (e.g. to continue or terminate the pregnancy), male partners’ behaviours ranged from being supportive to neutral or coercive in expressing their preference. These findings support pre-existing research documenting the partner’s influences on women’s sexual and reproductive health and decision-making.(Barbosa et al. 2009; Villela et al. 2012; Menezes and Aquino 2009)

Health care providers in this study uniformly encouraged women to continue their pregnancies and proactively educated women about the prevention of vertical transmission. Health care providers in Brazil and other contexts have reportedly misinformed or coerced pregnant HIV-positive women to terminate their pregnancies or undergo sterilisation (Orner et al. 2011; Cooper et al. 2007; Hopkins et al. 2005; International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS 2008). Given this reality, the fact that health care providers in our study gave accurate medical information on preventing vertical transmission to HIV-positive women is promising. Still, especially in light of the surrounding political legal context, Brazilian health providers may inadvertently or intentionally constrain women into continuing their pregnancies if education on preventing vertical transmission pre-empts an attempt to explore and facilitate women’s own pregnancy intentions.

The health system and greater health policies also play a role in shaping pregnancy outcomes for HIV-positive women, ultimately enabling, complicating or entirely precluding HIV-positive women’s access to safe abortion. Indeed, the lack of available, accessible and acceptable abortion services prevented some participants from successfully terminating their pregnancies, despite their desire to do so. There is broad support for the integration of HIV treatment and care with reproductive health services across health systems, but these discussions have largely neglected the delivery of abortion services even where it is legal. (Cooper et al. 2009; Gruskin et al. 2008)

Finally, some women who considered abortion worried about HIV-related stigma directed toward themselves or their infants while others who did not consider abortion were concerned with abortion-related stigma. In this setting and others, concurrent and competing stigmas related to HIV and to abortion complicate reproductive decision-making amongst HIV-positive women (Bui et al. 2010; Orner, de Bruyn, and Cooper 2011; Orner et al. 2010; Orner et al. 2011; Cooper et al. 2007; de Bruyn 2004; Craft et al. 2007; Ingram and Hutchinson 2000; Kavanaugh ML et al. 2013). Specifically, social norms that simultaneously stigmatise PT as well as people living with HIV and their becoming pregnant render any pregnancy decision by HIV-positive women socially unacceptable.

There are several limitations to this qualitative study. One limitation is the difficulty of assessing the relative weight and marginal contribution of each overlapping factor in women’s reproductive decision-making. Furthermore , this study explored factors that promote or deter HIV-positive women from PT where ART is universally available. These results cannot be extrapolated to analyses of PT in contexts lacking access to ART - only with longitudinal data could such conclusions be reached. Finally, because some women were not pregnant at the time of the interviews, there may also have been some recall bias as women reflected on their reproductive decision-making at the time of their pregnancy, and the time between pregnancy and interview is unclear.

Conclusion

This study explored the variable role of HIV in reproductive decision-making among HIV-positive Brazilian women. For some women, positive HIV status was the primary motivation for considering and seeking PT, whereas HIV was not a consideration in the decision to continue or terminate a pregnancy for others – particularly for those who did not contemplate abortion. Most women, regardless of their overall pregnancy intentions, were more strongly influenced by the same factors that HIV-negative women might consider, including sociocultural predisposition against abortion, desired family size and partner preferences, rather than HIV itself.

Corroborrating recent research, these findings suggest that the role of HIV in reproductive decision-making among HIV-positive women is increasingly being outweighed by other considerations but cannot be consistently predicted. Whereas it was previously assumed that HIV was the only factor influencing HIV-positive women to seek PT, the relative importance of HIV status for reproductive decision-making is likely to decline over time in a setting where ART is universally available. This apparent shift in the role of HIV not only raises important research questions going forward and underscores the importance of collecting and disaggregating data by HIV status: Such data will be necessary to fully explore the impact of universal access to ART on reproductive decision-making over time.

Indeed, decisions to continue or terminate a pregnancy are at once personal choices that reflect complex and community-specific intersections of legal, political, social and biomedical spheres. Although HIV-positive women in this study had access to ART, many participants were limited in their ability to seek and obtain abortion, when desired. Access to ART notwithstanding, the array of available, accessible and acceptable sexual and reproductive health services including other essential medicines invariably shapes HIV-positive women’s decisions to continue or terminate pregnancies – but to variable degrees, as this study reveals.

Abandoning the assumption that all HIV-positive women have similar pregnancy intentions is a necessary first step in providing sexual and reproductive health services and engaging in responsive policymaking that enable women to realise their decision to carry a pregnancy to term, or not.

In the future, public health researchers, providers and policymakers in Brazil and globally should anticipate that the determinants of pregnancy decisions are inter-related and context specific. Furthermore , women’s experience with abortion cannot be examined without considering the legality of services and access to ARVs. If the sexual and reproductive health and rights of HIV-positive women are to be met, efforts should be re-oriented to support – rather than limit – women as they contemplate abortion.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support of UNAIDS, UNIFEM, Brazilian National Department of STD/AIDS and Viral Hepatitis/Ministry of Health, the Foundation for Research Support of the State of Bahia (FAPESB), The HIV/AIDS Reference Center of the Bahia Department of Health (CEDAP/SESAB) and The Pathfinder Foundation. Additionally, we appreciate the support by the training grant entitled “HIV and Other Infectious Consequences of Substance Abuse (T32DA13911-12) and from the Lifespan/Tufts/Brown Center for AIDS Research (P30AI042853) from the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases.

References

- Barbosa RM, Pinho AA, Santos NS, Filipe E, Villela W, Aidar T. Induced abortion in women of reproductive age living with and without HIV/Aids in Brazil. Revista Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2009;14(4):1085–1099. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232009000400015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa RM, Pinho AA, Santos NS, Villela WV. Exploring the relationship between induced abortion and HIV infection in Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters. 2012;20(39 Suppl):80–89. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39633-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedimo AL, Bessinger R, Kissinger P. Reproductive choices among HIV-positive women. Social Science & Medicine. 1998;46(2):171–179. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair JM, Hanson DL, Jones JL, Dworkin MS. Trends in pregnancy rates among women with human immunodeficiency virus. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):663–668. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000117083.33239.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongain A, Berrebi A, Marine-Barjoan E, Dunais B, Thene M, Pradier C, Gillet JY. Changing trends in pregnancy outcome among HIV-infected women between 1985 and 1997 in two southern French university hospitals. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2002;104(2):124–128. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(02)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonstra Heather. Meeting the Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs of People Living with HIV. New York City: Guttmacher Policy Review; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui KC, Gammeltoft T, Nguyen TT, Rasch V. Induced abortion among HIV-positive women in Quang Ninh and Hai Phong, Vietnam. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2010;15(10):1172–1178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi BK, Hanh NT, Rasch V, Gammeltoft T. Induced abortion among HIV-positive women in Northern Vietnam: exploring reproductive dilemmas. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2010;12(Suppl 1):S41–S54. doi: 10.1080/13691050903056069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi BK, Rasch V, Thi Thuy Hanh N, Gammeltoft T. Pregnancy decision-making among HIV positive women in Northern Vietnam: reconsidering reproductive choice. Anthropology & Medicine. 2011;18(3):315–326. doi: 10.1080/13648470.2011.615909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D, Harries J, Myer L, Orner P, Bracken H, Zweigenthal V. "Life is still going on": reproductive intentions among HIV-positive women and men in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(2):274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D, Moodley J, Zweigenthal V, Bekker LG, Shah I, Myer L. Fertility intentions and reproductive health care needs of people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for integrating reproductive health and HIV care services. AIDS & Behavior. 2009;13(Suppl 1):38–46. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft SM, Delaney RO, Bautista DT, Serovich JM. Pregnancy decisions among women with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6):927–935. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruyn M. Safe abortion for HIV-positive women with unwanted pregnancy: a reproductive right. Reproductive Health Matters. 2003;11(22):152–161. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruyn M. Living with HIV: challenges in reproductive health care in South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2004;8(1):92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruyn M. Women, reproductive rights, and HIV/AIDS: issues on which research and interventions are still needed. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2006;24(4):413–425. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvaux T, Nostlinger C. Reproductive choice for women and men living with HIV: contraception, abortion and fertility. Reproductive Health Matters. 2007;15(29 Suppl):46–66. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)29031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz Debora. Aborto e saúde pública no Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2007;23(9):1992–1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floridia M, Tamburrini E, Tibaldi C, Anzidei G, Muggiasca ML, Meloni A, Guerra B, Maccabruni A, Molinari A, Spinillo A, Dalzero S, Ravizza M Pregnancy Italian Group on Surveillance on Antiretroviral Treatment in. Voluntary pregnancy termination among women with HIV in the HAART era (2002–2008): a case series from a national study. AIDS Care. 2010;22(1):50–53. doi: 10.1080/09540120903033268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman LA, Garcia SG, Diaz J, Yam EA. Brazilian obstetrician-gynecologists and abortion: a survey of knowledge, opinions and practices. Reproductive Health. 2005;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco P, Vimercati A, Fiore JR, Saracino A, Buccoliero G, Loverro G, Angarano G, Pastore G, Selvaggi L. Reproductive choice in individuals HIV-1 infected in south eastern Italy. Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 1999;27(3):173–177. doi: 10.1515/JPM.1999.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin S, Firestone R, Maccarthy S, Ferguson L. HIV and pregnancy intentions: do services adequately respond to women's needs? American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(10):1746–1750. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebling EM, Hardy E. Feelings related to motherhood among women living with HIV in Brazil: a qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2007;19(9):1095–1100. doi: 10.1080/09540120701294294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins K, Maria Barbosa R, Riva Knauth D, Potter JE. The impact of health care providers on female sterilization among HIV-positive women in Brazil. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(3):541–554. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. Brazil: Supreme Court Abortion Ruling a Positive Step. Washington D.C.: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram D, Hutchinson SA. Double binds and the reproductive and mothering experiences of HIV-positive women. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10(1):117–132. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasiliero de Geografia e Estatistica. [cited 22 February 2013];GDP figures for Brazilian municipalities reveal discrepancies in income generation 2005. 2013 Available from http://www.ibge.gov.br/english/presidencia/noticias/noticia_visualiza.php?id_noticia=354.

- International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS. Studies on abortion in India and Nepal. London, England: ICW; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone FD, Brettle RP, MacCallum LR, Mok J, Peutherer JF, Burns S. Women's knowledge of their HIV antibody state: its effect on their decision whether to continue the pregnancy. British Medical Journal. 1990;300(6716):23–24. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6716.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanniappan S, Jeyapaul MJ, Kalyanwala S. Desire for motherhood: exploring HIV-positive women's desires, intentions and decision-making in attaining motherhood. AIDS Care. 2008;20(6):625–630. doi: 10.1080/09540120701660361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh ML, Moore AM, Akinyemi O, Adewole I, Dzekedzeke K, Awolude O, Arulogun O. Community attitudes towards childbearing and abortion among HIV-positive women in Nigeria and Zambia. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2013;15(2):160–174. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.745271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenbaum SB, Hirky AE, Correale J, Goldstein RB, Johnson MO, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Ehrhardt AA. "Throwing the dice": pregnancy decision-making among HIV-positive women in four U.S. cities. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36(3):106–113. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.106.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline A, Strickler J, Kempf J. Factors associated with pregnancy and pregnancy resolution in HIV seropositive women. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40(11):1539–1547. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenti R, Mello Jorge MHP, Gotlieb SLD. A mortalidade materna nas capitais brasileiras: algumas caracteristicas e estimativa de um fator de ajuste. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia. 2004;7(4):449–460. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren S, Ottenblad C, Bengtsson AB, Bohlin AB. Pregnancy in HIV-infected women. Counseling and care--12 years' experiences and results. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1998;77(5):532–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCarthy S, Rasanathan JJK, Nunn A, Dourado I. ‘I did not feel like a mother’: The Challenges of Exclusive Formula Feeding Among HIV-Positive Women in Salvador, Brazil. AIDS Care. 2013;25(6):726–731. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.793274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCarthy S, Rasanathan JJK, Ferguson L, Gruskin S. The pregnancy decisions of HIV-positive women: the state of knowledge and way forward. Reproductive Health Matters. 2012;20(39):119–140. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massad LS, Springer G, Jacobson L, Watts H, Anastos K, Korn A, Cejtin H, Stek A, Young M, Schmidt J, Minkoff H. Pregnancy rates and predictors of conception, miscarriage and abortion in US women with HIV. AIDS. 2004;18(2):281–286. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401230-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzeo C, Flanagan E, Bobrow E, Pitter C, Marlink R. How the global call for elimination of pediatric HIV can support HIV-positive women to achieve their pregnancy intentions. Reproductive Health Matters. 2012;20(39):90–102. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39636-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes G, Aquino EM. Research on abortion in Brazil: gaps and challenges for the public health field. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2009;25(Suppl 2):S193–S204. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009001400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orner P, de Bruyn M, Cooper D. 'It hurts, but I don't have a choice, I'm not working and I'm sick': decisions and experiences regarding abortion of women living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13(7):781–795. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.577907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orner P, de Bruyn M, Harries J, Cooper D. A qualitative exploration of HIV-positive pregnant women's decision-making regarding abortion in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Social Aspects fo HIV/AIDS. 2010;7(2):44–51. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2010.9724956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orner PJ, de Bruyn M, Barbosa RM, Boonstra H, Gatsi-Mallet J, Cooper DD. Access to safe abortion: building choices for women living with HIV and AIDS. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2011;14:54. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos NJS, Barbosa RM, Pinho AA. Contextos de vulnerabilidade para o HIV entre mulheres brasilieras. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2009;25(suppl. 2):S321–S333. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009001400014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits AK, Goergen CA, Delaney JA, Williamson C, Mundy LM, Fraser VJ. Contraceptive use and pregnancy decision making among women with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 1999;13(12):739–746. doi: 10.1089/apc.1999.13.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Benthem BH, de Vincenzi I, Delmas MC, Larsen C, van den Hoek A, Prins M. Pregnancies before and after HIV diagnosis in a european cohort of HIV-infected women. European Study on the Natural History of HIV Infection in Women. AIDS. 2000;14(14):2171–2178. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200009290-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villela WV, Barbosa RM, Portella AP, de Oliveira LA. Motives and circumstances surrounding induced abortion among women living with HIV in Brazil. Revista Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2012;17(7):1709–1719. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232012000700009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, and United Nations Population Fund. Sexual and reproductive health of women living with HIV/AIDS: Guidelines on care, treatment and support for women living with HIV/AIDS and their children in resource-constrained settings. Geneva: 2006. [Google Scholar]