Abstract

Liver growth factor (LGF) is a hepatic mitogen purified by our group in 1986. In the following years we demonstrated its activity both in “in vivo” and “in vitro” systems, stimulating hepatocytes mitogenesis as well as liver regeneration in several models of liver injury. Furthermore, we established its chemical composition (albumin-bilirubin complex) and its mitogenic actions in liver. From 2000 onwards we used LGF as a tissue regenerating factor in several models of extrahepatic diseases.

The use of Liver growth factor as a neural tissue regenerator has been recently protected (Patent No US 2014/8,642,551 B2).

LGF administration stimulates neurogenesis and neuron survival, promotes migration of newly generated neurons, and induces the outgrowth of striatal dopaminergic terminals in 6-hidroxydopamine-lesioned rats. Furthermore, LGF treatment raises striatal dopamine levels and protects dopaminergic neurons in hemiparkinsonian animals. LGF also stimulates survival of grafted foetal neural stem cells in the damaged striatum, reduces rotational behaviour and improves motor coordination. Interestingly, LGF also exerts a neuroprotective role both in an experimental model of cerebellar ataxia and in a model of Friedrich´s ataxia. Microglia seem to be the cellular target of LGF in the CNS. Moreover, the activity of the factor could be mediated by the stimulation of MAPK´s signalling pathway and by regulating critical proteins for cell survival, such as Bcl-2 and phospho-CREB.

Since the factor shows neuroprotective and neurorestorative effects we propose LGF as a patented novel therapeutic tool that may be useful for the treatment of Parkinson´s disease and cerebellar ataxias.

Currently, our studies have been extended to other neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (Patent No: US 2014/0113859 A1).

Keywords: Ataxia, liver growth factor, neuroregeneration, neuroprotection, neurodegenerative diseases, Parkinson's disease, trophic factors

INTRODUCTION

The conventional pharmacological and surgical treatments concerning neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson´s disease (PD) or Alzheimer’s disease (AD), are no longer effective over time because they do not slow the disease progression. However, trophic factors such as glial derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) are being considered as promising tools for the treatment of these disorders due to their neuroprotective and neurorestorative potential. Following this approach, our group decided in the early 2000´s to evaluate the therapeutic ability of a novel compound with pleiotropic effects, in several experimental models of neurodegenerative diseases. This novel factor was known as Liver Growth Factor (LGF).

LGF (BACKGROUND)

The liver is one of the organs with greater capacity of regeneration. Rats recover liver total weight within 8 to 10 days after being subjected to a 70% partial hepatectomy [1]. The presence of one or more trophic factors in the serum of animals after partial hepatectomy is one of the various mechanisms that have been proposed for explaining this regenerative capacity of the liver. Furthermore, it is known that these factors are responsible for the extraordinary cell proliferation rates observed in the injured liver. During the 60s and 70s of past century, several authors performed both in vivo and in vitro studies to demonstrate the existence of one or several factors, in the blood of hepatectomized animals, involved in the observed hepatic growth. In 1972, Paul et al. found an increase in DNA synthesis (3H-thymidine uptake) in cell cultures of fetal rat liver that had grown in the presence of serum from partially hepatectomized rats, compared to similar cultures incubated with serum from normal rats [2]. Previously, Moolten y Bucher also observed an increase in DNA and protein synthesis in healthy animals that had been subjected to cross blood flow experiments with partially hepactomized rats [3]. In 1971, Fisher and colleagues demonstrated that the humoral factor, implicated in this hepatic regeneration phenomenon, was present in the blood from the portal vein and its concentration increased depending on the amount of liver that was removed after hepatectomy [4].

In 1986, after several attempts to purify this growth factor from serum [5], plasma [6], cytoplasmic extracts from liver [7] and platelets [8], Diaz-Gil et al. purified a 64 kDa molecule obtained from plasma of partially hepactomized rats [9]. This molecule was able to stimulate DNA synthesis and increase the hepatocyte mitotic index after i.p. injection in mice. Moreover, the administration of this purified molecule to primary culture of rat liver cells promoted DNA synthesis and the activity of the amino acids transport system, increased 22Na+ uptake, which is needed to initiate hepatocyte proliferation [9]. We named this entity as Liver Growth Factor (LGF).

Interestingly, several studies also described that LGF was only detectable in serum of both rats and humans with a previous hepatic or hepatic-biliary damage [9-2]. Furthermore, LGF purified from serum of humans with Hepatitis B showed almost identical characteristics to that obtained from serum of rats or pigs with hepatic transplant [12, 13].

CHEMICAL STRUCTURE OF LGF

The chemical structure of LGF was defined as an albumin-bilirubin complex after several studies comparing LGF and rat serum albumin in terms of absorption spectra, fluorescence, cellular dichroism, tryptics maps, amino acid composition, electrophoretic mobility, immunofluorescence, in vitro albumin-bilirubin complex formation, HPLC identification and biological activity in in vivo and in vitro assays [14]. In order to demonstrate that LGF was a serum albumin-bilirubin complex, Diaz-Gil et al. synthesized in vitro albumin-bilirubin complexes and they observed that the incubation of albumin with bilirubin induced the formation of a complex which showed the characteristic biological activity exhibited by LGF. However, albumin or bilirubin themselves showed no mitogenic activity in mice liver when they were administered independently [14]. The biological activity of the albumin-bilirubin complex seems to be linked to a conformational change in the albumin molecule. Finally, LGF was identified as bilirubin-δ or biliprotein [11]. In addition, other authors [15] confirmed that albumin-bilirubin complexes also act as hepatic growth factors.

BIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF LGF IN THE LIVER

The biological activity of LGF was first demonstrated in liver. LGF showed in vivo activity as a growth factor when it was intraperitoneally injected to rats or mice, because it increased: 1) DNA synthesis, 2) dry liver weight and 3) the number of cells expressing the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). These effects were accompanied by a transitory hyperplasia, without detecting severe immediate or permanent side effects, such as production of amyloids, fibrosis and mitochondrial or nuclear disturbances [16]. Long term action of LGF did not appear to alter homeostasis, since liver, pancreas, kidney and spleen did not show signs of degeneration or fibrosis one year after injection of the factor [16]. LGF activity was confirmed up to date in 18 laboratories working in different biological systems. In addition, the mitogenic activity initiated by LGF in rat liver in vivo seems to be mediated by TNF-α stimulation and portal vein endothelial cells could be the source of this cytokine [17].

LGF was able to stimulate regeneration in the damaged liver by the action of several hepatotoxins [18, 19]. The administration of LGF in a cirrhosis model with an irreversible hepatic lesion induced by CCl4, decreased fibrosis, restructured the hepatic parenchyma, diminished inflammation and necrosis, recovered liver and hemodynamic functions (portal venous pressure, hepatic arterial pressure, portosystemic shunt and systemic vascular resistance) and reduced ascites. Moreover, LGF produced a reduction of cirrhosis and fibrosis, and improved hepatic function when it was administered to a fibrosis–cirrhosis rat model generated by bile duct ligation [20, 21]. These studies also proposed that the anti-fibrotic activity of LGF could be due to the modulation of the activation state of hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts [21], and the synthesis inhibition of several fibrogenic mediators such as the transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) and the matrix metalloproteases 1 and 9 (MMP-2 y MMP-9) [20].

BIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF LGF IN EXTRAHEPATIC SITES

The effects exerted by LGF in other regions apart from the liver are summarized in Table 1. Several studies revealed the beneficial effects of LGF in the cardiovascular system. LGF treatment reduces blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) decreasing carotid artery fibrosis and increasing the number of vascular smooth muscle cells without altering the inner diameter or the average thickness of the artery [22]. Furthermore, two recent reports showed that the administration of LGF in the SHR model also produced the following regenerative cardiovascular effects: 1) restored the wall composition of intramyocardial vessels, 2) reduced left ventricular hypertrophy, 3) improved nitric oxide availability through the reduction of superoxide anion levels, and 4) normalized the plasmatic levels of several oxidative stress markers [23, 24]. LGF also exerted a considerable antioxidant activity in vitro due to its effectiveness as a scavenger of several reactive oxygen species involved in cardiovascular disorders [25]. In addition, this factor reduced hepatic steatosis and atherosclerotic plaques in a mouse model of atherosclerosis [26].

Table 1.

LGF activity as tisular / cellular regenerating factor in the liver and other peripheral organs after i.p. injection into mice or rats.

| Effect | Organ / Pathology / Cellular Targets | References |

|---|---|---|

| Antifibrotic activity | Liver | [18-21] |

| Artery walls and heart | [22, 23] | |

| Lung | [31] | |

| Antioxidant activity | Artery walls (hypertension) | [24, 25] |

| Anti-inflammatory activity | Liver | [19, 20] |

| Lung | [31] | |

| Antiapoptotic activity | Liver | [21] |

| Improve of biological function in pathological model systems |

Liver | [18-21] |

| Hypertension-heart | [22, 23] | |

| Atherosclerosis | [26] | |

| Lung | [31, 32] | |

| Testis | [27, 29] | |

| Cellular Targets of LGF | Hepatocytes | [16, 17] |

| Stellate cells (liver) | [21] | |

| Vascular endothelial cells | [17,22, 23] | |

| Smooth muscle cells | [22, 23] | |

| Leydig and stem cells (testis) | [29, 33] |

Interestingly, several studies showed the role of LGF in the field of testicular regeneration. The administration of LGF to rats with Leydig cells depletion through treatment with ethane dimethane sulphonate (EDS), stimulated testicular regeneration, prevented germ cell detachment and Sertoli cells damage promoting the growth of germ cells and stimulating the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors [27, 28]. In addition, LGF improved testicular regeneration and recovered spermatogenesis in mice treated with bisulfan, an agent that selectively destroys spermatogonial stem cells [29]. We should mention that the effects exerted by LGF in atherosclerosis, intramyocardial arteries, angiogenesis, testis, spinal cord and hepatocarcinoma cells were reflected in the Spanish patent 2010/ES200601018 [30].

On the other hand, LGF also acts as a tissue regenerator in experimental models of lung pathologies. Martínez-Galán and coworkers described that LGF improved lung function and partially reversed both lung fibrosis and matrix metalloproteases increase, in a lung fibrosis model induced by cadmium chloride CdCl2 [31]. Moreover, a recent study showed the ability of LGF to reverse emphysema in mice exposed to cigarette smoke. This work described the beneficial effects of LGF in a mouse model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, since the factor decreased systemic inflammation and improved lung morphology and physiology [32].

Taken together these results indicate that LGF is a pleiotropic factor, chemically characterized as an albumin-bilirubin complex, capable of stimulating cell proliferation and tissue regeneration in both hepatic and extrahepatic pathologies.

BIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF LGF IN NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES

Parkinson´s Disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder involving a progressive loss of dopaminergic (DA) neurons projecting from the substantia nigra (SN) to the striatum. Due to the therapeutic effects and pleiotropic actions exerted by LGF, in 2004 our group decided to evaluate the potential neuroprotective and / or neuroregenerative abilities of this factor in a rat model of PD generated by the administration of the dopaminergic neurotoxine 6-hidroxydopamine (6-OHDA).

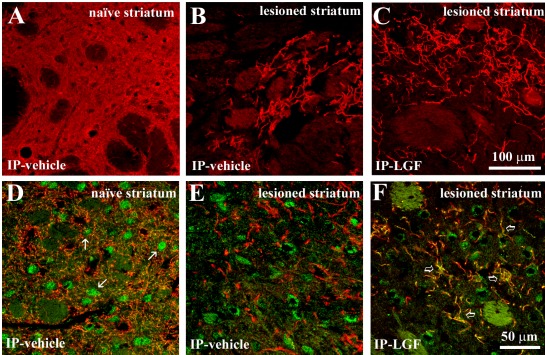

The study of the effects elicited by the intrastriatal (IS) or intraperitoneal (IP) administration of LGF in a 6-OHDA experimental model of PD showed that this factor induced the outgrowth of dopaminergic terminals and the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis) in the denervated striatum [34, 35] (Representative images in Fig. 1). The IP LGF treatment raised striatal expression of the dopamine transporter (DAT). The histological and biochemical quantification of the above mentioned dopaminergic parameters (Striatal TH+ fibers and DAT) was widely reflected in Gonzalo-Gobernado et al. 2013 [34] and Reimers et al. 2006 [35]. The intraperitoneal administration of LGF also increased striatal dopamine levels, and partially rescued dopaminergic neurons of the SN from the damage induced by 6-OHDA [34] (Table 2). Moreover, intrastriatally or intraperitoneally administered LGF improved motor function and coordination of the hemi-parkinsonian animals [34, 35]. The beneficial effects of IP LGF administration both on the dopaminergic system and on motor function are widely reflected in patent No. US 8,642,551 B2 [36]. Interestingly, the stimulation of the brain serotonin pathway by intraperitoneal injection of LGF is also described in this patent.

Fig. (1).

Liver growth factor stimulates TH and DAT expression in the striatum of hemiparkinsonian rats. Panels A, B and C show TH positive terminals in the naïve striatum (A) and lesioned striatum of vehicle treated rats (B) and in the lesioned lesioned striatum of IP-LGF treated rats (C). Panels D, E and F show double immunostaining for DAT (green) and TH (red) in the naïve striatum (D) and lesioned striatum of vehicle treated rats (E) and in the lesioned striatum of IP-LGF treated animals (F). TH (red) and DAT (green) immunoreactivity was reduced in the lesioned striatum of vehicle-treated rats (B, red and E, green), as compared with the naïve striatum (A, red and D green) and with the lesioned striatum of the LGF group (C, red and F, green). Moreover, DAT immunostaining in the naïve striatum of vehicle-treated was confined to small spots in the striatal parenchyma that probably represent neuronal cell bodies (white arrows in D). Note how DAT (green) is mainly expressed in TH-immunopositive (red) growing terminals in the striatum of rats receiving LGF, (F, yellow, clear arrows). Scale bar: A-C, 100 µm, and D-F, 50 µm. Figure modified and reproduced from [34] [Gonzalo-Gobernado et al. PLoS ONE 8(7): e67771. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067771] in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Table 2.

Effects of LGF on different cellular phenotypes of the CNS.

| Phenotype | Neurodegenerative Disease | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| DA Neurons | Parkinson´s Disease | Neuroprotection vs 6-OHDA toxicity (SNpc). | [34] |

| Cerebellar Neurons | Cerebellar Ataxia | Neuroprotection of deep nuclei neurons from 3-AP toxicity. Preservation of calbindin+ terminals of Purkinje cells that synapse with neurons of the cerebellar deep nuclei. | [50] |

| Spinal Cord Neurons | Friedreich’s Ataxia | Neuroprotective effect on sensory neurons located in the lumbar spinal cord. | [49] |

| Microglia | Parkinson´s Disease | Transient activation. Long term anti-inflammatory response. |

[34, 35] |

| Cerebellar Ataxia | Prevention of long term activation. | [50] | |

| Adult NSC´s | Parkinson´s Disease | NSC´s proliferation Neurogenesis. Neuronal differentiation. |

[37] |

| Foetal NSC´s | Parkinson´s Disease | Survival of Neural stem cell grafts. | [38] |

On the other hand, we also wondered whether LGF could promote adult neurogenesis in 6-OHDA lesioned rats. Thus, we evaluated the effects of intraventricular (ICV) LGF infusion over the neural stem cells (NSC) that persist in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of adult hemi-parkinsonian rats. The ICV administration of LGF was able to induce: 1) proliferation of neural precursors located in the SVZ, 2) mobilization and migration of neuronal precursors (neuroblasts) towards the injured striatum, and 3) differentiation of neuroblasts into neurons in the lesioned striatum of hemiparkinsonian rats [37] (Table 2). In summary, this study showed that LGF stimulates neurogenesis when infused into the lateral ventricle of adult 6-OHDA–lesioned rats and, therefore, the usefulness of LGF for neuronal replacement therapies was proposed.

LGF did not only stimulate endogenous adult neural stem cells, but it also promoted the viability of NSC grafts in the damaged striatum of hemiparkinsonian rats [38]. The study showed that LGF promoted NSC survival (Table 2), since an increased number of grafted stem cells were observed both in healthy and dopamine-depleted striatum of animals that were treated with this factor.

The biochemical, histological and behavioral analyses of the IS, ICV and IP administration of LGF did not show any remarkable side effects both in the hemiparkinsonian and in the naïve animals examined. Specifically, the histological studies of LGF treated animals did not reveal the presence of any tumor or teratoma in the brain regions analyzed (striatum, lateral ventricles, olfactory bulb, hippocampus, third ventricle and hypothalamus). However, we should point out that a few ICV-LGF treated animals showed small luminal thickenings of proliferating cells protruding into the lateral ventricles. Most of these proliferating cells were also inmunopositive for Isolectin B4, a marker of microglia / macrophages [37].

Summarizing, the IS infusion of LGF induced a local sprouting of the TH+ terminals in the lesioned striatum and slightly improved the rotational behavior [35]. However, the IP administration of LGF exerted a significant neuroprotective effect both over in the dopaminergic neurons of the SNpc and in the lesioned striatum of the hemiparkinsonian rats [34]. In addition, the lesioned animals that were treated intraperitoneally with LGF showed a better motor behavior compared with the hemiparkinsonian rats that received the IS infusion. On the other hand, the data obtained from the ICV infusion experiments indicated that LGF neither restored motor behaviour nor ameliorated the dopaminergic deficit using this method of administration [37]. Taking together, these results point out that the intraperitoneal administration of LGF is the best method of treatment due to its long term effectiveness over the PD pathology and lack of invasivity.

One of our main goals was to determine the target cells and molecular effectors that mediate the actions of LGF administration in 6-OHDA lesioned rats. The results showed that acute IS LGF infusion stimulated microglia proliferation and increased the number of microglial cells with amoeboid morphology [35], which is part of the activation response of this cell type in the central nervous system [39, 40]. ICV LGF infusion also promoted an increase of microglial proliferation and its activation [37]. Moreover, LGF enhanced expression of several markers related to microglial activation since a single intraperitoneal injection of the factor was able to stimulate transient expression of GLUT-5 (Glucose transporter-5) and OX6 (a major histocompatibility complex II protein) in the striatum of hemiparkinsonian rats [34]. Acute IP LGF treatment also increased cell proliferation, measured by analyzing PCNA expression and the number of proliferating microglial cells (OX6 + / PCNA+) observed in the striatum. Because chronic intraperitoneal administration of LGF restored these parameters (OX6 and GLUT-5) to baseline levels [34], we think that microglial activation is an early and transient effect produced by this factor in experimental PD. Taken together these results indicated that microglia could be the main target of LGF in the mammalian brain (Table 2) but we cannot exclude astroglia [34, 37] and vascular endothelial cells [17, 37], two cell types that also react to LGF.

As previously indicated, TNF-α seems to be the initiator of the mitogenic cascade of LGF in the liver [17]. LGF also stimulated TNF-α secretion in cultures of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) but did not up-regulate two endothelial adhesion molecules which play a key role in the pro-inflammatory effects mediated by this cytokine: ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1) and VCAM-1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule 1) [17].For these reasons, we decided to study whether TNF-α could be a molecular effector of LGF actions observed in the injured brain. Interestingly, a single injection of LGF was able to induce a transient TNF-α protein expression and immunoreactivity in the lesioned striatum of hemiparkinsonian rats [34]. Since TNF-α-positive cells in the striatal parenchyma also expressed OX6 and exhibited the morphology of microglia, we proposed that the acute administration of this factor could directly induce the synthesis of TNF-α in this cell type [34]. However, chronic IP injections of LGF reduced both TNF-α levels and OX6 expression in the dopaminergic system of hemiparkinsonian rats [34]. Thus, these results indicated that long term LGF treatment induces an anti-inflammatory effect against the neurotoxicity elicited by 6-OHDA in this model of PD (Table 2).

Bcl-2 is an anti-apoptotic protein widely related to neural cell survival [41, 42]. Our results showed that LGF treatment increased Bcl-2 expression in striatum and mesencephalon of hemiparkinsonian rats [34, 38]. Since the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax was not affected by LGF administration, we proposed that the factor was probably related to mechanisms that enhance dopaminergic neurons survival [34].

The study of the effects exerted by IP LGF administration in a model of PD provided, for the first time, information about possible signal transduction pathways involved in the actions of the factor. Thus, the administration of a single dose of LGF was able to activate the MAPK/ERK pathway in the lesioned striatum of hemiparkinsonian rats [34]. Since this pathway is implicated in the regulation of several remarkable cellular events, including cell proliferation, survival and differentiation, and is also induced by other growth factors, we suggested that the neuroprotective activity of LGF in hemiparkinsonian animals could be regulated by the MAPK/ERK pathway [34]. Furthermore, the acute LGF administration also stimulated the phosphorylation of Cyclic AMP response-element binding protein (CREB) [34]. This transcription factor is activated after the stimulation of MAPK/ERK1/2 and other signaling pathways [43]. Interestingly, CREB regulates the expression of several markers involved in the homeostasis of the dopaminergic system [44] and is also related to neuronal survival [45] and the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 [46].Taken together these results suggested that the activation of the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway and its subsequent relationship with CREB phosphorylation and Bcl-2 expression could be part of the main mechanisms responsible for the neuroprotective action exerted by LGF in the 6-OHDA experimental model of PD [34].

Cerebellar ataxia

Cerebellar ataxias (CA) include a heterogeneous group of infrequent diseases characterized by a lack of motor coordination mainly related with dysfunction of the cerebellum and associated neuronal circuits and spinocerebellar afferents [47]. In light of the beneficial effects exerted by LGF in a rat model of PD, we decided to study the potential neuroregenerative and/or neuroprotective action of this factor in the 3-acetylpyridine (3-AP) experimental model of cerebellar ataxia (CA) in rats. Our results showed that the intraperitoneal administration ofLGF stimulated the expression of the neuronal marker NeuN and the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 in the brainstem of 3-AP lesioned rats [48]. This treatment also reduced extracellular concentration of glutamate and prevented chronic microglial activation in the cerebellum (Table 2). Both phenomena could explain the protective action exerted by LGF on the calbindin-positive terminals of Purkinje cells that synapse with neurons of the cerebellar deep nuclei (Table 2). Furthermore, LGF treatment significantly improved motor coordination of ataxic animals, maintaining this effect throughout the entire experimental period analyzed [48].

Friedreich´s Ataxia

Friedreich´s ataxia (FA) is a severe disorder with autosomal recessive inheritance that leads to a partial silencing of frataxin (FXN) transcription, causing a multisystem disease that includes neurological and non-neurological damage. Due to the positive effects produced by LGF in the rat model of cerebellar ataxia, we decided to analyze the therapeutic properties of the intraperitoneal administration of this growth factor in an FA experimental model [ transgenic mice of the FXNtm1MknTg (FXN) YG8Pook strain]. Preliminary results showed that LGF treatment exerted a neuroprotective effect on sensory neurons located in the lumbar spinal cord (Table 2) and reduced cardiac hypertrophy [49]. Both events may be due to increased expression of FXN promoted by the factor in the spinal cord and the heart, since neurodegeneration in both structures is directly related to the protein deficiency. Interestingly, LGF seemed to stimulate AKT phosphorylation in the spinal cord. Furthermore, LGF also reduced oxidative stress in skeletal muscle and improved motor coordination in this experimental model of FA [49].

Perspectives for LGF as a Potential Treatment in Alzheimer´s Disease

The therapeutic activity of LGF in Alzheimer`s disease is based on the following facts: 1) In the USA patent No US 8,642,551 B2 above mentioned we showed that LGF injection to normal rats was able to stimulate serotonin pathway in three different areas [36], one of them, the hippocampus, is tightly related to Alzheimer`s disease pathology. This area is essential in learning and memory processes. 2) LGF exhibits a remarkable anti-inflammatory activity [19, 20, 31] as well as antioxidant activity [24, 25]. Both effects are considered to be closely related with Alzheimer`s disease pathology. 3) LGF stimulates neurogenesis in hemiparkinsonian rats [37]. Several lines of evidence suggest a correlation between adult neurogenesis and learning. Thus, it has been proposed that a decline in hippocampal neurogenesis contributes to a physiological reduction in brain functions such as hippocampal-dependent memory and learning. 4) Preliminary studies carried out in a transgenic model of Alzheimer`s disease [Tg2576 (APPSWE) mice] showed that intraperitoneal administration of LGF improved learning behavior, reduced glial reactivity associated with AD, and up-regulated the expression of HSP70, a chaperone that allows the correct folding of proteins. In light of these activities of the LGF, US Patent Agency considered the extension to Alzheimer´s disease as “continuation in part” (US 2014/0113859 A1) [51] to the previously patent referred No US 8,642,551 B2 [36].

In summary, this mini-review highlights the beneficial effects of LGF and its abilities as a neuroprotective and neurorestorative agent in several models of neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, we propose LGF as a patented novel therapeutic tool that may be useful for the treatment of Parkinson´s disease, cerebellar ataxias, Friedrich´s ataxia and Alzheimer´s disease.

CURRENT & FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

A key event in the pathogenesis of most neurodegenerative processes is an exacerbated inflammatory activity of microglia. Our current studies try to evaluate if LGF modulates the functional homeostasis in the Central Nervous System through its anti-inflammatory and andantioxidant actions. The experimental efficiency of this treatment may have clinical impact, but first it will be necessary to establish the in vitro synthesis of this neurorestorative factor, which is at present the main aim of our laboratory.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the editorial for its invitation to contribute with a review article in RPCN. This work was funded by the Spanish Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS PI060315 and FIS 2010/172), Agencia Pedro Laín Entralgo (NDG7/09), Fundación MAPFRE Medicina and Fundación Ataxias en Movimiento. RGG and LCF were the recipients of Contrato de Personal de Apoyo a la Investigación (Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias) and Agencia Pedro Laín Entralgo fellowships, respectively. We are grateful to Maria José Asensio, Ana Gómez Soria and Manuela Vallejo Muñoz for their help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bucher NL, Malt R. Boston: Little Brown and Co; 1971. Regeneration of Liver and Kidney . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul D, Leffert H, Sato G, Holley RW. Stimulation of DNA and protein synthesis in fetal-rat liver cells by serum from partially hepatectomized rats . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 1972;69(2 ):374–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.2.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moolten FL, Bucher NL. Regeneration of rat liver transfer of humoral agent by cross circulation . Science . 1967;158(798):272–4. doi: 10.1126/science.158.3798.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher B, Szuch P, Levine M, Fisher ER. A portal blood factor as the humoral agent in liver regeneration . Science . 1971;171(971):575–7. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3971.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morley CG, Kingdon HS. The regulation of cell growth I. Identification and partial characterization of a DNA synthesis stimulating factor from the serum of partially hepatectomized rats. Biochim Biophys Acta . 1973;308(2):260–75. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(73)90156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg M, Strecker W, Feeny D, Ruhenstroth-Bauer G. Evidence for and characterization of a liver cell proliferation factor from blood plasma of partially hepatectomized rats . Horm Metab Res . 1980;12(3):94–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-996212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaBrecque DR, Bachur NR. Hepatic stimulator substance physicochemical characteristics and specificity . Am J Physiol . 1982;242(3):G281–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1982.242.3.G281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell WE, McGowan JA, Bucher NL. Partial characterization of a hepatocyte growth factor from rat platelets . J Cell Physiol . 1984;119(2):183–92. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041190207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Díaz-Gil JJ, Escartin P, Garcia-Canero R, Trilla C, Veloso JJ, Sanchez G, et al. Purification of a liver DNA-synthesis promoter from plasma of partially hepatectomized rats . Biochem J. 1986; 235(1):49–55. doi: 10.1042/bj2350049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Díaz-Gil JJ, Sanchez G, Santamaria L, Trilla C, Esteban P, Escartin P. Liver DNA synthesis promoter activity detected in human plasma from subjects with hepatitis . Hepatology . 1986;6(4):658–61. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840060419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Díaz-Gil JJ, Sanchez G, Trilla C, Escartin P. Identification of biliprotein as a liver growth factor . Hepatology . 1988;8(3):484–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Díaz-Gil JJ, Gavilanes JG, Garcia-Canero R, Garcia-Segura JM, Santamaria L, Trilla C, et al. Liver growth factor purified from human plasma is an albumin-bilirubin complex . Mol Biol Med . 1989;6(3):197–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Díaz-Gil JJ, García-Cañero R, de Foronda M, Pérez de Diego J, Cereceda RM, Trilla C, et al. Purification and characterization of the Liver Growth Factor from Pig serum . Hepatology . 1992;16(169A ):499–0. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Díaz-Gil JJ, Gavilanes JG, Sanchez G, Garcia-Canero R, Garcia-Segura JM, Santamaria L, et al. Identification of a liver growth factor as an albumin-bilirubin complex . Biochem J. 1987; 243(2 ):443–8. doi: 10.1042/bj2430443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abakumova O, Fedorova LM, Popov AA, Li VS, Arkhangelskaya SL, Bachmanova GI. Effects of albumin-bilirubin complexes with syngeneic or allogeneic albumin on DNA and protein synthesis in liver and spleen of partially hepatectomized rats . J Hepatol . 1994;21(6):947–52. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80600-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Díaz-Gil JJ, Rua C, Machin C, Cereceda RM, Garcia-Canero R, de Foronda M, et al. Hepatic growth induced by injection of the liver growth factor into normal rats . Growth Regul . 1994;4(3):113–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Díaz-Gil JJ, Majano PL, Lopez-Cabrera M, Sanchez-Lopez V, Rua C, Machin C, et al. The mitogenic activity of the liver growth factor is mediated by tumor necrosis factor alpha in rat liver . J Hepatol . 2003;38(5):598–604. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Díaz-Gil JJ, Rua C, Machin C, Cereceda RM, Guijarro MC. Berlín: Springer Verlag; Hepatic recovery of dimethylnitrosamine-cirrhotic rats after injection of the Liver growth factor NATO ASI Series "Cell Biology" ; pp. 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Díaz-Gil JJ, Munoz J, Albillos A, Rua C, Machin C, Garcia-Canero R, et al. Improvement in liver fibrosis, functionality and hemodynamics in CCI4-cirrhotic rats after injection of the Liver Growth Factor . J Hepatol . 1999;30(6):1065–72. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Díaz-Gil JJ, Garcia-Monzon C, Rua C, Martin-Sanz P, Cereceda RM, Miquilena-Colina ME, et al. The anti-fibrotic effect of liver growth factor is associated with decreased intrahepatic levels of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 and transforming growth factor beta 1 in bile duct-ligated rats . Histol Histopathol . 2008;23(5):583–91. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Díaz-Gil JJ, Garcia-Monzon C, Rua C, Martin-Sanz P, Cereceda RM, Miquilena-Colina ME, et al. Liver growth factor antifibrotic activity in vivo is associated with a decrease in activation of hepatic stellate cells . Histol Histopathol . 2009;24(4 ):473–9. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Somoza B, Abderrahim F, Gonzalez JM, Conde MV, Arribas SM, Starcher B, et al. Short-term treatment of spontaneously hypertensive rats with liver growth factor reduces carotid artery fibrosis, improves vascular function, and lowers blood pressure . Cardiovasc Res . 2006;69(3):764–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conde MV, Gonzalez MC, Quintana-Villamandos B, Abderrahim F, Briones AM, Condezo-Hoyos L, et al. Liver growth factor treatment restores cell-extracellular matrix balance in resistance arteries and improves left ventricular hypertrophy in SHR . Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol . 2011;301(3):H1153–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00886.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Condezo-Hoyos L, Arribas SM, Abderrahim F, Somoza B, Gil-Ortega M, Diaz-Gil JJ, et al. Liver growth factor treatment reverses vascular and plasmatic oxidative stress in spontaneously hypertensive rats . J Hypertens . 2012;30(6):1185–94. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328353824b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Condezo-Hoyos L, Abderrahim F, Conde MV, Susin C, Diaz-Gil JJ, Gonzalez MC, et al. Antioxidant activity of liver growth factor, a bilirubin covalently bound to albumin. Free Radic Biol Med . 2009;46(5):656–62. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surra JC, Guillen N, Barranquero C, Arbones-Mainar JM, Navarro MA, Gascon S, et al. Sex-dependent effect of liver growth factor on atherosclerotic lesions and fatty liver disease in apolipoprotein E knockout mice . Histol Histopathol . 2010;25(5):609–18. doi: 10.14670/HH-25.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lobo M, Arenas M, Huerta L, Sacristan S, Perez-Crespo M, Gutierrez-Adan A, et al. Liver growth factor (LGF) induces testicular regeneration in EDS-treated rats and increases protein levels of class B scavenger receptors . Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metabol. 2014 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00329.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martín-Hidalgo A, Arenas MI, Sacristán S, Huerta L, Díaz-Gil JJ, Carrillo E, et al. Rat testis localization of VEGFs and VEGF receptors in control and testicular regeneration stimulated by the liver growth factor (LGF) . FEBS J . 2007;274(suppl.1):296. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez-Crespo M, Pericuesta E, Perez-Cerezales S, Arenas MI, Lobo MV, Diaz-Gil JJ, et al. Effect of liver growth factor on both testicular regeneration and recovery of spermatogenesis in busulfan-treated mice . Reprod Biol Endocrinol . 2011;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Díaz-Gil JJ. Use of the liver growth factor as a pleiotropic tissue regenerator . 2010 ES200601018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez-Galan L, del Puerto-Nevado L, Perez-Rial S, Diaz-Gil JJ, Gonzalez-Mangado N, Peces-Barba G. Liver growth factor improves pulmonary fibrosis secondary to cadmium administration in mice . Arch Bronconeumol . 2010;46(1):20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez-Rial S, Del Puerto-Nevado L, Giron-Martinez A, Terron-Exposito R, Diaz-Gil JJ, Gonzalez-Mangado N et al. Liver growth factor treatment reverses emphysema previously established in a cigarette smoke exposure mouse model . Am J Physiol Lung Cellular Mol Physiol . 2014 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00293.2013. doi 10.1152/ajplung.00293.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martín-Hidalgo A, Lobo MV, Sacristán S, Huerta L, Gómez-Pinillos A, Díaz-Gil JJ, et al. Rat testicular regeneration after Eds administration is stimulated by the liver growth factor . FEBS J. 2007;274(suppl.1):296–0. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalo-Gobernado R, Calatrava-Ferreras L, Reimers D, Herranz AS, Rodriguez-Serrano M, Miranda C, et al. Neuroprotective activity of peripherally administered liver growth factor in a rat model of Parkinson's disease . PloS one . 2013;8(7):e67771–0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reimers D, Herranz AS, Diaz-Gil JJ, Lobo MV, Paino CL, Alonso R, et al. Intrastriatal infusion of liver growth factor stimulates dopamine terminal sprouting and partially restores motor function in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats . J Histochem Cytochem . 2006;54(4):457–65. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6805.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Díaz-Gil JJ. Use of liver growth factor (LGF) as a neural tissue regenerator . 2014 US8642551B2. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalo-Gobernado R, Reimers D, Herranz AS, Diaz-Gil JJ, Osuna C, Asensio MJ, et al. Mobilization of neural stem cells and generation of new neurons in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats by intracerebroventricular infusion of liver growth factor . J Histochem Cytochem . 2009;57(5):491–502. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.952275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reimers D, Osuna C, Gonzalo-Gobernado R, Herranz AS, Diaz-Gil JJ, Jimenez-Escrig A, et al. Liver growth factor promotes the survival of grafted neural stem cells in a rat model of Parkinson's disease . Curr Stem Cell Res Ther . 2012;7(1):15–25. doi: 10.2174/157488812798483421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graeber MB, Streit WJ, Kreutzberg GW. The microglial cytoskeleton vimentin is localized within activated cells in situ . J Neurocytol . 1988;17(4):573–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01189811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vilhardt F. Microglia phagocyte and glia cell . Int J Biochem Cell Biol . 2005;37(1):17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ziv I, Offen D, Haviv R, Stein R, Panet H, Zilkha-Falb R, et al. The proto-oncogene Bcl-2 inhibits cellular toxicity of dopamine possible implications for Parkinson's disease . Apoptosis . 1997;2(2):149–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1026408313758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frebel K, Wiese S. Signalling molecules essential for neuronal survival and differentiation . Biochem Soc Trans . 2006;34(Pt 6):1287–90. doi: 10.1042/BST0341287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arthur JS, Fong AL, Dwyer JM, Davare M, Reese E, Obrietan K, et al. Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 mediates cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation and activation by neurotrophins . J Neurosci . 2004;24(18):4324–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5227-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lim J, Yang C, Hong SJ, Kim KS. Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene transcription by the cAMP-signaling pathway involvement of multiple transcription factors . Mol Cell Biochem . 2000;212(1-2):51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herold S, Jagasia R, Merz K, Wassmer K, Lie DC. CREB signalling regulates early survival, neuronal gene expression and morphological development in adult subventricular zone neurogenesis . Mol Cell Neurosci . 2011;46(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riccio A, Ahn S, Davenport CM, Blendy JA, Ginty DD. Mediation by a CREB family transcription factor of NGF-dependent survival of sympathetic neurons . Science . 1999;286(5448):2358–61. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marmolino D, Manto M. Past, present and future therapeutics for cerebellar ataxias . Curr Neuropharmacol . 2010;8(1):41–61. doi: 10.2174/157015910790909476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Calatrava-Ferreras L, Gonzalo-Gobernado R, Reimers D, Herranz AS, Jimenez-Escrig A, Díaz-Gil JJ, et al. Neuroprotective role of liver growth factor “LGF” in an experimental model of cerebellar ataxia . Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(10):1905 6–73. doi: 10.3390/ijms151019056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bazan E, Calatrava L, Reimers D, Gonzalo-Gobernado R, Herranz AS, Casarejos MJ, et al. Liver growth factor "LGF" up-regulates frataxin protein expression and reduces oxidative stress in Friedreich's ataxia transgenic mice 9th FENS Forum of Neuroscience; 2014; Milano Italy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calatrava-Ferreras L, Gonzalo-Gobernado R, Reimers D, Herranz AS, Jimenez-Escrig A, Diaz-Gil JJ, et al. Neuroprotective Role of Liver Growth Factor "LGF" in an Experimental Model of Cerebellar Ataxia . Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(10):19056–73. doi: 10.3390/ijms151019056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Díaz-Gil JJ. Use of liver growth factor (LGF) as a neural tissue regenerator . 2014b US8642551B2. Continuation-in-part US 2014/0113859 A1. [Google Scholar]