Abstract

Mosquito-borne arboviruses are emerging world-wide as important human and animal pathogens. This makes assays for their accurate and rapid identification essential for public health, epidemiological, ecological studies. Over the past decade, many mono- and multiplexed assays targeting arboviruses nucleic acids have been reported. None has become established for the routine identification of multiple viruses in a “single tube” setting. With increasing multiplexing, the detection of viral RNAs is complicated by noise, false positives and negatives. In this study, an assay was developed that avoids these problems by combining two new kinds of nucleic acids emerging from the field of synthetic biology. The first is a “self-avoiding molecular recognition system” (SAMRS), which enables high levels of multiplexing. The second is an “artificially expanded genetic information system” (AEGIS), which enables clean PCR amplification in nested PCR formats. A conversion technology was used to place AEGIS component into amplicon, improving their efficiency of hybridization on Luminex beads. When Luminex “liquid microarrays” are exploited for downstream detection, this combination supports single-tube PCR amplification assays that can identify 22 mosquito-borne RNA viruses from the genera Flavivirus, Alphavirus, Orthobunyavirus. The assay differentiates between closely-related viruses, as dengue, West Nile, Japanese encephalitis, and the California serological group. The performance and the sensitivity of the assay were evaluated with dengue viruses and infected mosquitoes; as few as 6–10 dengue virions can be detected in a single mosquito.

Keywords: reverse-transcription PCR, Luminex direct hybridization assay, Self-avoiding Molecular Recognition System (SAMRS), Artificially Expanded Genetic Information System (AEGIS), dengue virus

1. Introduction

Arthropod-borne (arbo) viruses are a genetically diverse group of RNA viruses transmitted by arthropod vectors. Well known among these are mosquitoes, which carry viruses that cause eastern equine encephalitis (EEE), St. Louis encephalitis (SLE), La Crosse (LAC) encephalitis, and western equine encephalitis (WEE) (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/arbor/arbdet.htm). West Nile virus is responsible for large recent global outbreaks of neurological disease (Lanciotti et al. 1999; Gubler, 2007). Dengue hemorrhagic fever outbreaks in the Americas (Weinhold, 2010; Brathwaite Dick et al., 2012) are increasing, as is the emergence of vaccination-associated viscerotropic disease due to yellow fever virus (Douce et al., 2010; Jentes et al., 2011).

Many arboviruses previously regarded as being problematic only overseas are becoming important in the United States. For exmple, recent outbreaks of dengue in Florida (Centers for Disease and Prevention, 2010), http://www.floridahealth.gov/%5C/diseases-and-conditions/dengue/index.html (site visited June 2014) and Texas (Murray et al., 2013) suggests vulnerability within the United States for a virus that may infect ca. 390 million humans worldwide annually (Bhatt et al., 2013). Effective vaccines have proven difficult to develop (Weaver and Reisen, 2010), and increasing commerce, urbanization, and population is likely to create increased incidence. For example, the distribution of Japanese encephalitis (Hills et al., 2010; Campbell et al., 2011; Centers for Disease and Prevention, 2011) and Murray valley encephalitis (Kienzle and Boyes, 2003; Douglas et al., 2007) is shifting in response to changing societal factors. From 1973 through 2011, 58 reports of travel-associated Japanese encephalitis (JE) were published in the United States among travelers from non-endemic countries. Similarly, traveler-associated Chikungunya virus in the U.S. has increased alarmingly as a result of an outbreak in the Caribbean starting in December 2013 (PAHO 2014).

Unfortunately, the clinical manifestations of many infections from mosquito-borne arboviruses need not indicate specific causative agent. Infections can even be asymptomatic (Reiter, 2010). Thus, arboviruses pose a major challenge for diagnostics. However, the first line of defense is public health surveillance. Here, molecular diagnostics tools that target specific viral RNA sequences in trapped mosquitoes would be helpful, at least in principle. Thus, many researchers have reported mono- and multiplexed nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) that detect arboviruses in biological samples.

Most of these assays exploit a reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as an amplification format. Subsequent detection is done by either agarose gel electrophoresis (followed by ethidium bromide staining) or hybridization with molecular probes (Houng et al., 2001; Scaramozzino et al., 2001; de Morais Bronzoni et al., 2005; Chao et al., 2007; Naze et al., 2009; Yeh et al., 2010; Grubaugh et al., 2013a; Grubaugh et al., 2013b).

However, singleplexed nucleic acid amplification tests are expensive if run individually; running many singleplexed assays for all possible viruses can be expensive. Accordingly, it would be desirable to have a single assay that is able to rapidly identify all of the most important mosquito-borne pathogens. Such assays would enhance public health protection through their ability to detect any arboviruses present in an environment, potentially allowing for notice in advance of human cases, and allowing for rapid intervention strategies that may reduce risk of disease transmission. They would also support epidemiological and ecological research (Sim et al., 2009).

In this study, a single-tube high-throughput xMAP Luminex assay panel based on PCR amplification was developed to detect 22 mosquito-borne arboviruses relevant to public health in the U.S. This assay exploited three new kinds of nucleic acids to avoid classical problems in multiplexed amplification of nucleic acids.

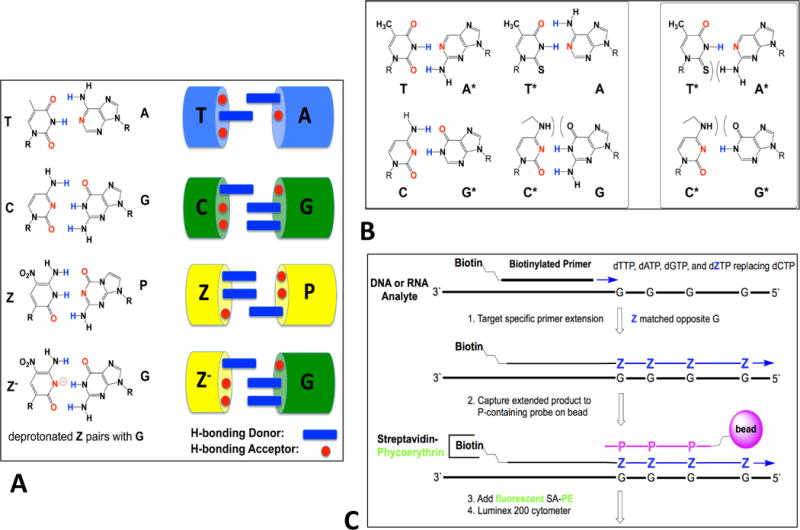

First, to support high levels of multiplexing with minimal need to engineer complex primer sets, the recently described “self avoiding molecular recognition systems”, SAMRS (Hoshika et al., 2010) was employed (Figure 1B). SAMRS nucleotides look like DNA, but are built from four special nucleotide analogs (A*, T*, G*, and C*). A* pairs with natural T, T* pairs with natural A, G* pairs with natural C, and C* pairs with natural G. However, but A* does not pair with T* and G* does not pair with C*. Therefore, SAMRS primers do not bind to other SAMRS primers, allowing an indefinite number of primers to be used to amplify an indefinite number of DNA without primer-primer interactions and their associated artifacts.

Figure 1.

(A) Components of an artificially expanded genetic information system (AEGIS), which adds up to eight nucleotides that form 4 additional base pairs to the four standard nucleotides, by strategically rearranging hydrogen bonding patterns on these. The Z:P pair is exploited in this work. (B) A schematic showing that by strategic removal of hydrogen bonding groups, a self-avoiding molecular recognition system (SAMRS) can be obtained. (C) Conversion allows a template G to direct the incorporation of Z by primer extension using a mismatching between G and deprotonated Z.

To support amplification with little target bias, a nested PCR architecture was used. Instead of having the external primers built from standard nucleotides, the external primers contained components of an “artificially expanded genetic information system (AEGIS) (Figure 1A) (Yang et al., 2010). AEGIS begins with the recognition that the Watson-Crick pairs follow two rules of complementarity (a) size complementarity (large purines pair with small pyrimidines) and (b) hydrogen bonding complementarity (hydrogen bond donors from one nucleobase match hydrogen bond acceptors on its complement). Further, the standard Watson-Crick pairs (G:C and A:T) exploit only two of 6 possible hydrogen bonding patterns, allowing for the addition of nucleobases with different hydrogen bonding patterns (Figure 1 A).

Completing Watson-Crick pairing, AEGIS adds up to 8 bases and 4 pairs by shuffling hydrogen bonding groups AEGIS bases pair (http://www.firebirdbio.com/ProductPage.aspx: Benner et al., 2010). This allows AEGIS DNA to pair with other AEGIS DNA, without pairing with any standard DNA. This allows the external primers in the nested PCR architecture to form “orthogonally”; they do not bind off-target, and, in particular, they cannot bind to mosquito DNA or RNA, no matter how much of it is present in a sample. In the current study, the nested PCR amplification used external primers containing the AEGIS nucleosides P (2-amino-8-(1′-β-d-2′-deoxyribofuranosyl) imidazo [1,2-a]-1,3,5-triazin-4(8H)-one) and Z (6-amino-5-nitro-3-(1′-β-d-2′-deoxyribofuranosyl) -2(1H)-pyridone). These pair, with the Z:P pair forming with Watson-Crick geometry.

A third technology exploited recently developed standard-to-AEGIS conversion strategies to improve the specificity of hybridization on Luminex beads and the overall signal (Yang et al., 2013). Conversion exploits specially designed polymerase conditions to add Z bases to a tag via Z:G mispairing (Figure 1C) in the absence of dCTP (conversion). This “conversion” architecture creates a Z-containing extension tag that is captured by a bead-bound oligonucleotide containing P (the Z:P pair is stronger than the C:G pair). The conversion architecture improves the ability of the Luminex instruments to detect amplimers, producing higher fluorescent signals without the possibility of competition from any natural oligonucleotides, even in complex biological samples.

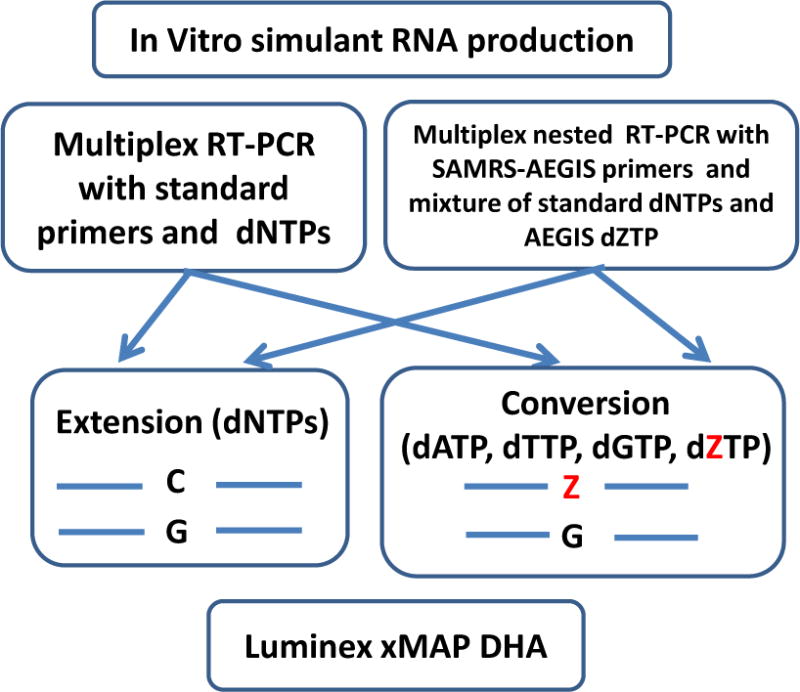

A schematic showing the multiplexed Luminex xMAP assays panel developed in this study is presented in Figure 2. Twenty-two mosquito-borne arboviruses (Table 1) medically important in the United States were selected using the CDC web site (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/arbor/arbdet.htm) and PubMed resources. They are the members of three families: Flaviviridae, Togaviridae and Bunyaviridae. The members of the first two families are positive single-stranded (ss) RNA viruses (group IV); members of the Bunyaviridae family are negative ss RNA viruses (group V).

Figure 2.

Overview of the Luminex xMAP multiplexed assays platform developed to detect 22 various mosquito borne arboviruses. RNA simulants or full dengue serotypes viral RNAs were RT-PCR-amplified in two different reactions. One (conventional) was performed with standard dNTPs and primers; the other (nested) with sets of SAMRS-AEGIS internal and AEGIS external, and a mixture of standard dNTPs and AEGIS dZTP. Each amplicon was subject to the “extension PCR” and “conversion PCR”. Finally, four PCR-amplicons obtained for each target were analyzed by multiplexed Luminex panel.

Table 1.

Viruses in this study.

| Family/Genus | Viruses and abbreviations | Primer identity |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Flaviviridae/Flavivirus Group IV, positive ssRNA |

West Nile (WN) | Forward-WNm1, Reverse -WNm1 |

| Japanese encephalitis (JE) | Forward–JE m1, Reverse -JE m1 | |

| Saint Louis encephalitis (SLE) | Forward–SLEVm1, Reverse -SLEVm1 | |

| Yellow fever (YF) | Forward–YF m3, Reverse -YF m3 | |

| Dengue serotype 1 (D1) | Forward-D1, Reverse-Den(1,3) | |

| Dengue serotype 2 (D2) | Forward-D2, Reverse -D (2,4) | |

| Dengue serotype 3 (D3) | Forward-D3, Reverse -D (1,3) | |

| Dengue serotype 4 (D4) | Forward-D4, Reverse -D (2,4) | |

| Murray valley encephalitis (MVE) | Forward—MVE, Reverse –MVE | |

| Rocio (Rocio) | Forward—Rocio, Reverse -Rocio | |

|

| ||

| Togaviridae/Alphavirus Group IV, positive ssRNA |

Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) | Forward -EEEm1, Reverse -EEEm1 |

| Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis (VEE) | Forward -VEEm1, Reverse -VEEm1 | |

| Western Equine Encephalitis (WEE) | Forward -WEEm1, Reverse -WEEm1 | |

| Chikungunya (ChV) | Forward-ChV, Reverse-ChV | |

|

| ||

| Bunyaviridae/Orthobunyavirus Group V negative ssRNA |

California encephalitis (CE) | Forward -CE, Reverse -CE |

| Jamestown Canyon | Forward -JTC Reverse -JTC | |

| La Crosse encephalitis (LAC) | Forward -LAC, Reverse -LAC | |

| Keystone (KS) | Forward- KS, Reverse -KS | |

| Snowshoe Hare (SSH) | Forward -SSH, Reverse-SSH | |

| San Angelo (SA) | Forward 2-CAcom, Reverse 1-CAcom | |

| Serra do Navio (SN) | Forward 2-CAcom, Reverse 1- CA –com | |

| Melao (Mel) | Forward- Mel, Reverse -Mel | |

Another innovation allowed the exploitation of patterns of evolution to design primers that were most likely to yield useful amplification. Here, an in-house primer design software tool (StrainTargeter) begins by analyzing a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) that is built from all of the virus sequences in the database. StrainTargeter then scans the MSA searching for regions of conserved sequence within a specified species, strain, or subtype. Conserved regions target all species within a viral species; serotypes are distinguished in variable regions. StrainTargeter then takes as input desired melting temperatures and other user-specified criteria to give final sets of primers and probes. To ensure minimal cross-reactivity, these are then ranked based on built-in BLAST-ing of the sequences against the mosquito (and, if desired human) genome databases, as well as NCBI’s RNA virus database, to avoid potential off-target interference.

To develop the assays, viral genomes were replaced by short segments of RNA simulants synthesized by T7 RNA polymerase. These were used as templates for PCR-amplification; the amplicons were initially identified by agarose gel electrophoresis followed by staining with ethidium bromide and molecular hybridization with specific probes on Luminex instrument. Because simulants present an environment perhaps less than completely challenging, a single-tube comprehensive high-throughput xMAP Luminex panel based on the PCR amplification was then also evaluated using the full genomic dengue serotypes viruses and laboratory infected dengue vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes.

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to develop the comprehensive and sensitive 22-fold multiplex panel to detect arboviruses in North America. For the PCR-amplification based assays, multiplication obviously has the reverse effect on the assay sensitivity and introduction of synthetic nucleotides in PCR amplification and Luminex detection compounds not only prevent the PCR noise but increased the specific signal thus greatly mitigate this obstacle. Due to the high panel sensitivity it might be potent either to monitor the mosquitoes’ pools or to test the human and animal serum.

The diagnostic panel, as well as the StrainTargeter software, is available on request and the scientific audience is welcome to test any virus of the panel. This will open the possibilities to evaluate the panel in whole mosquitoes infected with still other viruses, and possibly even with human and animal serum.

This notwithstanding, for the clinical and veterinarian laboratories equipped with a Luminex instrument, this diagnostic panel should be an inexpensive approach to low-cost multiplexing, with the cost of detecting 22 targets not materially larger in terms of labor than the cost of detecting a few.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses targeted in this study

2.2. Oligos design

Primers and probes (Tables 1–2 and Appendix A. Supplementary data, Table A1) were designed using the StrainTargeter software that was developed in house. Sequences within the viral genome to be targeted were identified from multiple sequence alignments (MSA) built from all publicly available genetic sequence databases, but especially GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) and the virus pathogens resource (ViPR) (http://www.viprbrc.org/brc/home.do?decorator=vipr). A BLAST search showed that the primer and probe sequences were not closely similar to other sequences in these databases.

Table 2.

Hybrid SAMRS-AEGIS primers and AEGIS (APTC) probes used in this study. All reverse primers are 5′-biotinylated; the probes are 5′-amino –C12- modified. The AEGIS tags in the primers are underlined. P, AEGIS nucleotide. A*,T*,G*,C*, SAMRS nucleotides.

| Oligos primers/probes |

Sequences, 5′-3′ | Genome Region (bp) |

Gene/region targeting |

GenBank Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward WNm1 primer | CTAPTCCPCCAPCPAPC CGCGTGTTGTCCTTG*A*T*T*G | 149–167 | Capsid protein C | KF367469.1 |

| Reverse WNm1 primer | CAGPAAGPGGTPGPTPG CACACCTCTCCATCGA*T*C*C*A | 279–298 | KF367469.1 | |

| WN probe | APPTTCACAPCAATTPCTCC | 245–264 | KF367469.1 | |

| Forward JE m1 primer | CTAPTCCPCCAPCPAPC GACCAACGTCAGG*C*C*A*C | 10612–10628 | 3′-UTR | NC_001437 |

| Reverse JE m1 primer | CAGPAAGPGGTPGPTPG GGGTCTCCTCTAACCTCT*A*G*T*C | 10748–10769 | NC_001437 | |

| JE probe | CACPPCCCAAPCCTCPTCTA | 10705–10724 | NC_001437 | |

| Forward SLE m1 primer | CTAPTCCPCCAPCPAPC TGGCACGTAGGCT*G*G*A*G | 10560–10576 | 3′-UTR | EU566860.1 |

| Reverse SLEm1 primer | CAGPAAGPGGTPGPTPG CAGACAGCACCTTTAGC*A*T*G*C | 10613–10633 | EU566860.1 | |

| SLE probe | CAPACCAPAAATPCCACCT | 10509–10690 | EU566860.1 | |

| Forward YF m3 primer | CTAPTCCPCCAPCPAPC GTGCATTGGTCTGCAA*A*T*C*G | 25–44 | 5′-UTR | NC_002031 |

| Reverse YF m3 primer | CAGPAAGPGGTPGPTPG CCATATTGACGCCCA*G*G*G*T | 146–164 | NC_002031 | |

| YF probe | PAPCPATTAPCAPAPAACTPAC | 91–112 | NC_002031 | |

| Forward D1 primer | CTAPTCCPCCAPCPAPC GTCTTTCAATATGCTGAAA*C*G*C*G | 105–127 | Capsid protein C | FJ639679.1 |

| Forward D2 primer | CTAPTCCPCCAPCPAPC GAGGCCACAAACCATG*G*A*A*G | 10455–10474 | 3′-UTR | JX073928.1 |

| Forward D3 primer | CTAPTCCPCCAPCPAPC GTCTATCAATATGCTGAAA*C*G*C*G | 103–128 | Capsid protein C | EU482596.1 |

| Forward D4 primer | CTAPTCCPCCAPCPAPC ATGCGCCACGGAA*G*C*T*G | 10363–10379 | 3′-UTR | GQ199883.1 |

| Reverse D (1,3) primer | CAGPAAGPGGTPGPTPG TGAGAATCTCTTCGCCAAC*T*G*T*G | 152–174 (D1) | FJ639679.1 | |

| 153–175 (D3) | EU482596.1 | |||

| Reverse D (2,4) primer | CAGPAAGPGGTPGPTPG GGAGGGGTCTCCTCT*A*A*C*C | 10501–10519 (D2) | JX073928.1 | |

| 10403–10421 (D4) | GQ199883.1 | |||

| D1 probe | CPAPAAACCPCPTPTCAACT | 128–147 | FJ639679.1 | |

| D2 probe | CPCATPPCPTAPTPPACTAP | 10480–10499 | JX073928.1 | |

| D3 probe | APAAACCPTPTPTCAACTPP | 131–151 | EU482596.1 | |

| D4 probe | PCPT PPCATATTPPACTAPC | 10383–10402 |

GQ199883.1 NC_000943 |

|

| Forward MVE primer | CTAPTCCPCCAPCPAPC TGATCGCCATTCC*A*A*C*C | 535–551 | Polyprotein propeptide | |

| Reverse MVE primer | CAGPAAGPGGTPGPTPG GGTGTCATCACACATAA*A*T*C*C | 594–614 | NC_000943 | |

| MVE probe | PTCPPATTCPAPCCATTPAC MVE | 571–590 | NC_000943 | |

| Forward—Rocio primer | CTAPTCCPCCAPCPAPC CAAGAACCCAGTTGACA*C*A*G*G | 1883–1903 | AY632542 | |

| Reverse –Rocio primer | CAGPAAGPGGTPGPTPG GGGAACAAATGGATTGA*C*C*GT*C | 2015–2036 | AY632542 | |

| Rocio probe | PAPAACCTACATPATCTCACTCC | 1977–1999 | AY632542 |

Amplifying on the StrainTargeter workflow, sequences were downloaded family-by-family, to allow large batch downloads. The families examined were: Arenaviridae, Bunyaviridae, Caliciviridae, Coronaviridae, Filoviridae, Flaviviridae, Hepeviridae, Herpesviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Picornaviridae, Poxviridae, Reoviridae, Rhabdoviridae, and Togaviridae. All family files were split by species and genomic segment if necessary. Files were filtered to remove sequences with large size discrepancies, large portions of missing data (signified by multiple “N”’s within the sequence), or those that did not have four nucleotides present in the sequence (removing experimental sequences present in GenBank). Each individual species was aligned with MUSCLE v3.8.31 (using default options). From these alignments, a database of consensus sequences was created for each family. These consensus sequences were then clustered, using the in-home created algorithm, to group similar species together (with a threshold of 55% identity). Clustered species were then aligned, again with MUSCLE, to create the final MSAs that were used by StrainTargeter. By having similar viruses clustered, common amplification primers for several species could be design. This will help to both reduce the complexity in the assay, as well as allow more targets to be added.

Two common primers (forward and reverse) were designed to target both the SA and SN viruses, members of the California encephalitis serogroup. Two common reverse primers were designed to target dengue serotypes 1 and serotype 3 viruses, and dengue serotypes 2 and 4 viruses, respectively. The remaining viral amplicons are primed with the individual target-specific set of forward and reverse primers (Tables 1 and 2).

Single-stranded (ss) DNA oligonucleotides to make viral RNA simulants, as well as all primers and capture probes for the Luminex xMAP direct hybridization assays (DHA) that contained only standard nucleotides (Appendix A, Tables A1 and A2) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA). All reverse primers were 5′-biotinylated. All probes were 5′-amino –C12-modified (5AmMC12).

Primers and capture probes containing artificial SAMRS and AEGIS nucleotides (Table 2) were synthesized on ABI 394 and ABI 3900 synthesizers in-house; they are also available from Firebird Biomolecular Sciences LLC (www.firebirdbio.com). Primers and capture probes were designed to complement a majority of the strains from each of the target viruses. For the simulants, ssDNA oligonucleotides (Amplimers, Appendix A. Supplementary data Table A2) were chosen arbitrarily to represent a single strain.

2.3. In vitro production of viral RNA simulants via using transcription by T7 RNA polymerase

RNA simulants corresponding to a segment of one strain of each virus (Table 1) were produced in vitro by T7 RNA polymerase-dependent transcription. Single-stranded DNA oligos (amplimers, Appendix A, Supplementary data, Table A2) were purchased from IDT and PCR amplified. Each oligonucleotide contained T7 promoter universal sequence (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) at its 5′-end. Double-stranded PCR-amplicons were used as the templates for in vitro transcription reactions.

PCR was set up in 1X JumpStart reaction buffer (10 mM Tris –HCl, pH 8.3; 50 mM KCl; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 0.001% (w/v) gelatin) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The other components of the reaction mixture were (in a total volume of 100 μL): 2.5 ng/μL DNA oligo; 0.4mM dNTPs(Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA); 0.4 μM each, Forward T7 primer and Reverse target-specific primer; JumpStart Taq DNA polymerase (2 units, Sigma), nuclease-free ddH2O (added to create a final volume of 100 μL). After the initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 minutes, 35 cycles of amplification were performed (94 °C for 30 seconds, 55 °C for 30 seconds, and 72 °C for 1 minute). A final extension cycle was run at 72 °C for 5 minutes. Each PCR product (in 100 μL) was ethanol-precipitated and dissolved in nuclease–free dd H2O (12 μL). The resulting PCR products were sequenced in both directions (ICBR, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL) and about 2.5–5 pmol of the concentrated PCR product was used as a T7-DNA template to make RNA simulants.

In this study, a T7 RNA polymerase-dependent transcription reaction mixture (20 μL) was set up in a 1X transcription buffer (40 mM Tris, pH7.8, 20 mM NaCl, 18 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine HCl, 10 mM DTT; Life Technologies). The reaction mixture contained ATP, CTP, GTP, and UTP (2 μL of 75 mM stock solutions, NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA), DNA template (2.5–5 pmol, purified and concentrated PCR product); T7 RNA polymerase (2 μL of a 200 U/μL to give 20 U/μL final concentration, Austin, TX, USA). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 8–12 hours. Turbo DNase was then added (2 U per reaction mixture, Life Technologies) to remove DNA template. The mixtures were then incubated at 37 °C for 15–20 minutes. RNA products were isolated by phenol-chloroform extraction and dissolved in nuclease-free water (20 μL). RNA products were resolved by 3 % TBE agarose-gel electrophoresis and quantitated by their UV absorbance at 260 nm. The purity of RNAs was evaluated from their A260/A280 ratio. For pure RNA, a ratio of 1.8–2.1 is expected. The absence of template DNA in the RNA samples was confirmed by conventional PCR with Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) and the ethidium-bromide gel. Samples were aliquoted and kept at −80°C.

Monoplex PCRs were first performed using each target RNA simulant separately to assess the efficacy of the primers in PCR cycling, as well as to determine the sensitivity of the assay. Reactions were then optimized under multiplexed conditions to minimize cross-amplification or cross-hybridization resulting from possible sequence similarity between targets.

2.4. Reverse transcription PCR

Twenty two -fold multiplexed nested one-step RT-PCRs with SAMRS-AEGIS primers were carried out in 1X Reaction mix (Life Technologies) with RNA simulant (4 ng/μL) in a final volume of 20 μL accordingly to the Invitrogen protocol for the SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR with Platinum Taq (Life Technologies). The reaction mixture contained 0.2 mM of dZTP; 0.025μM each of 22 pairs forward and Reverse hybrid SAMRS-AEGIS target-specific primers; 0.25 μM External AEGIS Forward and Reverse-biotinylated primers; 2.5 units RT/Platinum Taq enzyme Mix. Additional 1.5 mM MgSO4 were added to the RT-PCR buffer. Cycling conditions were: one cycle of the cDNA synthesis and pre-denaturation (53 °C for 30 minutes and 94 °C for 2 minutes), 55 cycles of PCR (94 °C for 15 seconds, 53 °C for 30 seconds, and 70 °C for 30 seconds) and final extension at 72°C for 5 minute. A “no-target” PCR negative control was included with each assay run. To favor incorporation of biotin-labelled reverse primers to maximize hybridization sensitivity, the second PCR was performed with only reverse biotinylated primer (reverse primer extension reaction, RPER).

2.5. Digestion of excess primers and dNTPs

To destroy excess primers and deactivate dNTPs prior to RPER, ExoSAP-IT enzyme mixture (2μL, Affymetrix, Cleveland, Ohio, USA) were added to aliquots (5 μL) of standard or SAMRS-AEGIS nested PCR. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes and the enzyme mixture was destroyed by heating at 80 °C for 20 minutes. Treated PCR products were added directly to the Reverse Primer Extension reaction.

2.6. Reverse primer extension reaction (RPER)

Briefly, a RPER (20 μL) was set up in 1 X ThermoPol Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 8.8 at 25 °C; NEB, MA, USA) with 3 μL of each ExoSAP-treated RT-PCR product, 5′-biotinylated external (common) Reverse AEGIS primer (0.2μM), and Vent (exo-) DNA polymerase (1 unit per reaction, NEB, MA, USA). Without conversion (an “extension” reaction), dNTPs (final 0.2 mM each) were added. For the dZ incorporation into the final amplicon (“conversion”), nucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dTTP, dGTP, and dZTP, final concentration 0.2 mM of each) were added. The “extension” and “conversion” reaction mixtures were incubated in DNA Engine® Multi-Bay Thermal Cyclers (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 95 °C for 1 min, followed by 20 cycles (94 °C for 20 seconds, 55 °C for 30 seconds, 72 °C for 30 seconds). A final incubation was run at 72 °C for 1 minute. Reaction mixtures were then quenched with 4 mM EDTA.

For standard RT-PCR products, a set of 22 reverse target-specific primers (0.2 μM each) was added to the “extension” or “conversion” reactions. The other reaction components were the same as above.

2.7. Probe coupling to Luminex MicroPlex carboxylated microspheres

Capture probes modified with an amino-C12 linker at the 5′- end were coupled to Luminex MicroPlex carboxylated micro-spheres (“beads”)(Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) by a carbodiimide-based procedure according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, for each combination of probe and bead set (Table 5), 2.5 million Luminex beads were resuspended in 0.1 M MES buffer (morpholine ethane sulfonic acid, 50 μL, pH 4.5, Sigma-Aldrich), with probe (4 μL of 0.1 mM stock to give 0.4 nanomole final concentration), and treated twice with 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylamino-propyl]-carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, 5 μL of a 10 mg/mL solution, Thermo Scientific/Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) at room temperature for 30 min, rinsed in Tween 20 (0.02% aqueous solution), then rinsed with a sodium dodecylsulfate solution (0.1%), and resuspended in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) to the final volume of 100μL.

Table 5.

PCR amplicons in this study

| Target identity | WN 1 |

YF 2 |

JE 3 |

SLE 4 |

EEE 5 |

WEE 6 |

VEE 7 |

D1 8 |

D2 9 |

D3 10 |

D4 11 |

MVE 12 |

SN 13 |

Mel 14 |

SSH 15 |

Racio 16 |

KS 17 |

LAC 18 |

JTC1 19 |

JTC2 19 |

CE 20 |

SA 21 |

ChV 22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplicon size, base pairs, (bp) | 150 | 140 | 158 | 74 | 100 | 138 | 147 | 70 | 65 | 70 | 59 | 80 | 124 | 119 | 107 | 154 | 101 | 160 | 153 | 153 | 118 | 123 | 85 |

2.8. Luminex direct hybridization assay (DHA)

Luminex DHA (Dunbar, 2006) was performed accordingly to the “no wash” Luminex protocol (http://www.luminexcorp.com/Support/SupportResources/). In a pilot experiment ”wash” and “no wash” Luminex protocols were compared; no differences were found between two protocols when applied to our target- specific probes’ design. Briefly, aliquots (5 μL) of each extension or conversion reaction were transferred to 96-well plates (96-well PCR thermo polystyrene plates; Costar Technologies, Coppell, TX, USA). Hybridization buffer (25 μL of 2 X Tm 0.4 M NaCl; 0.2 M Tris, 0.16 Triton X-100, pH 8.0) containing totally 2,500 target-specific probe-coupled each microsphere types. Microspheres were vortexed and sonicated for 20 seconds. The total volume was adjusted to 50 μL by 20 μl of ddH20. 25 μl of ddH20 were added to each Background well (negative control). Hybridization was performed at 55 °C accordingly to the direct hybridization protocol (DHA) provided by Luminex: 95 °C for 5 min, cool to 55 °C at a speed of 0.1 °C/second, 15 min at the hybridization T 55° C. Tm buffer (25 μL of 1X) containing streptavidin-R-phycoerythrin (2 μg, PJRS14, PROzyme, Hayward, CA, USA) were added to the each hybridization mixture, which was then incubated at 55 °C for 5 min. Hybridization reactions were carried out in triplicate, and “no-target” controls were run in replicates of 6. Beads were analyzed for internal bead color and R-phycoerythrin reporter fluorescence using a Luminex 200 analyzer (Luminex xMAP Technology, Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) and the xPonent Software solutions. The median reporter fluorescence intensity (MFI) was computed for each bead type in the sample. The instrument’s gate setting was established before the samples were run, and was maintained throughout the course of the study.

2.9. Dengue viruses

Dengue viruses (serotypes 1–4) (Table 3) were obtained from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention as cell culture medium stocks. Dengue 1 virus (GenBank accession no. JQ675358, originally isolated from a human infected in Key West, FL in 2010) was kindly provided by the Florida Department of Health Bureau of Laboratories (Shin et al., 2013). These viruses were previously propagated on monolayer’s of African green monkey kidney cells (Vero), mosquito (C6/36), or mouse cells in tissue culture using standard methods (Yamada et al., 2002). Viral titers were also evaluated by TaqMan real-time PCR and the ratio of physical to viable virions (PFU) was ~100.

Table 3.

Dengue viruses and strain information*.

| Virus | Strain | Identification designation | Isolated by | Isolated from | Source | Titer (pfu/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dengue 1 | Hawaii | TC00835 WSV | A. Sabin, Children’s Hospital Research foundation, Cincinnati, OH | Human 02/9/1944 | CDC | 1.6×105 |

| Dengue 2 | New Guinea C | M29898 WSV | A. Sabin, Children’s Hospital Research foundation, Cincinnati, OH | Human 04/30/1944 | CDC | 2×104 |

| Dengue 3 | H-87 | TC00881 WSV | G. Sather, Univ. Pittsburg, Pittsburg, PA | Human 08/31/1956 | CDC | 1.6×105 |

| Dengue 4 | H-241 | TC00594 WSV | G. Sather, Univ. Pittsburg, Pittsburg, PA | Human 08/28/1956 | CDC | 4×106 |

| Dengue 1 Key West | BOL-KW010 | GenBank accession no. JQ675358 | L. Stark, Florida Department of Health | Human 2010 | FMEL | 4.8×107 |

Viral titers are reported in plaque forming units (pfu)/ml. Each plaque is assumed to have risen from single virions. The sources of viruses include the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory (FMEL).

2.10. Oral Infection of mosquitoes

The Aedes aegypti mosquitoes were F2 progeny of larvae collected from Key West, FL. The Ae. albopictus mosquitoes used were F5 progeny of adults collected on the campus of the Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory (FMEL) in Vero Beach, FL. Mosquito eggs were hatched in enamel pans (24×36×5 cm) with tap water (1.0 liter) and larval food (0.2 g, equal parts of brewer’s yeast Sacchromyces spp. and lactalbumin). Newly hatched larvae were rinsed free from larval food and redistributed in enamel pans at a density of 200 larvae per pan along with additional larval food (0.2 g). Additional food was added to each pan every other day during development of the immature stages. Mosquitoes were reared at 24 ± 0.5 °C with a 14:10 light:dark photoperiod. Pupae were placed in water-filled cups and held in 0.3 meter3 cages until emergence to adulthood. Adult mosquitoes were provided with 20% sucrose solution and water for nourishment.

For infection, 8–10 day old female mosquitos were allowed to feed on defibrinated bovine blood infected with dengue-1 virus (6.3 ± 0.2 Log10 pfu equivalents/mL of Dengue 1, BOL-KW010) at 30°C using an artificial blood feeding system (Hemotek). The virus titer of blood and mosquito samples was gauged using a standard curve method (Alto et al., 2008). This method compares the known titer of a positive standard control, as determined by plaque assay and qRT-PCR, with the titer of unknown samples as determined by qRT-PCR.

Mosquitoes were deprived of sucrose, but not water, 48 hours before feeding trials. Fully engorged females were held individually in cages (8 × 3 cm, height × diameter) with oviposition substrate at 30°C. After 12 days, a non-infectious blood meal was given to these mosquitoes after oviposition (approximately four days) mosquitoes were individually stored in microcentrifuge tubes −80°C and later were tested for infection. For each individual, the legs of adult females were dissected from bodies, and the legs and body of each female were tested separately for the presence of DENV-1 RNA. The body and legs from each female mosquito were separately homogenized with a TissueLyser (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in 2-mL flat-bottom vials containing 0.9 mL BA-1diluent and two zinc-plated steel BBs. Samples were then centrifuged (3,148 × g for 4 minutes at 4°C) and subject to nucleic acid isolation and titered by TaqMan real-time PCR (Table 4).

Table 4.

The Dengue 1 virus (Key West) titers in the infected Aedes albopictus (54–73) and Aedes aegypti (75–78) mosquito bodies.

| Mosquito identity | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 62 | 69 | 71 | 73 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 |

| Body titer, genomes/mL | n/a | 42.1×103 | 8.06×103 | 4.02×103 | 17.9×103 | 15.6×103 | 20×103 | 1.4×103 | n/a | 4.57×103 | n/a | 1.25×103 |

2.11. Nucleic Acid Isolation

Nucleic acids (NAs) were isolated from samples of clarified homogenates (250 μL) using the MagNA Pure LC Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The procedure was performed accordingly to the manufacture protocol on MagNA Pure LC Instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Samples included both mosquitoes’ bodies and viral stocks in cell culture medium. The isolation procedure was based on magnetic-bead technology. The samples were lysed by incubation with a special buffer (Roche Diagnostics) containing a chaotropic salt (guanidine isothiocyanate) and Proteinase K. Magnetic Glass Particles (MGPs) were added to the lysates. Total NAs contained in the samples were bound to MGPs surfaces. Unbound substances were then removed by several washing steps, and finally, purified total nucleic acids were eluted with low-salt buffer (50 μL, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0).

3. Results

3.1. Oligoes design and RNAs production

Twenty-two-fold multiplexed one step RT-PCR panel for detection of the mosquito-borne arboviruses medic ally important for the North America were selected (Table 1) to assemble and develop xMAP Luminex assays diagnostic panel based on PCR amplification and using the artificial SAMRS-AEGIS technology (Yang et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2013).

To allow unique targeting of RNA viruses, a custom primer design software (StrainTargeter) was created. This software takes a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) as an input, scans the MSA searching for regions of conserved sequence within a specified species, strain, or subtype and attempts to perform primer design using user-specified criteria (including melting temperature, length, GC content, etc.). If fully conserved sequence is not found, StrainTargeter attempts to create multiple primers in the same location to fully capture the desired set.

After the primers and their amplicons are designed, StrainTargeter designs probes within the amplicons that both capture the specified species, strain or subtypes specified, while avoiding any other targets within the same project. The final sets of primers and probes are then BLASTed against genomes of the user’s choice (e.g. mosquito and, to support human diagnostics, the human genome), as well as NCBI’s RNA virus database. This allows the primers to avoid binding off-target. Once all sets of primers and probes are designed for a multiplex assay, a secondary BLAST is performed to ensure that no combination of primers for any target within the assay will result in off-target amplification within the mosquito, human, or any viral genome in NCBI’s RNA virus database.

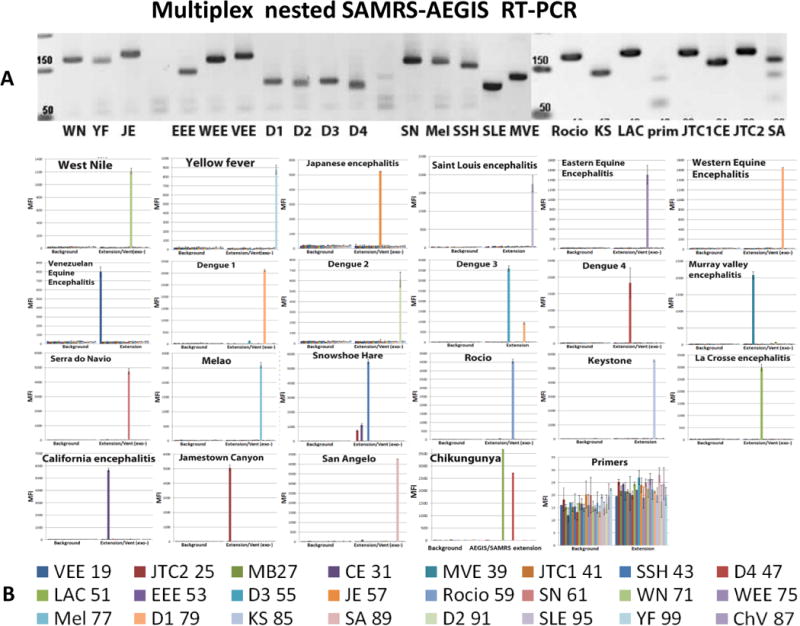

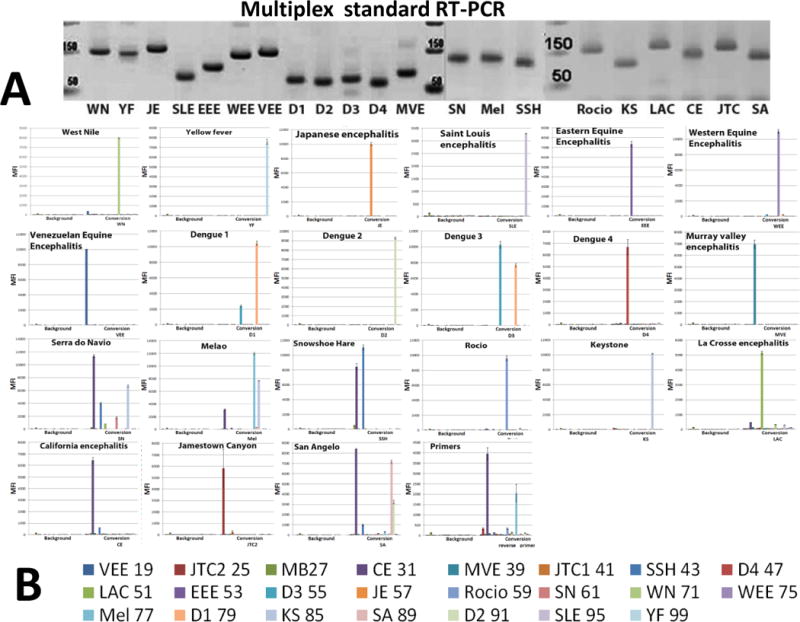

Viral simulant RNAs were produced in vitro by transcription of the appropriate templates using T7 RNA polymerase. In pilot experiments, SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR with Platinum Taq (Life Technology) was found to be more sensitive and robust than other enzyme combinations tested, and thus able to support the nested PCR amplification with external primers containing the nonstandard P nucleotide, which pairs with the Z nucleotide. The target-specific standard or hybrid SAMRS-AEGIS forward and reverse primer pairs designed for the panel were tested first by monoplexed one-step RT-PCR with viral RNA simulants. Each monoplexed RT-PCR produced the expected amplicon, which was visualized by the ethidium-bromide staining following electrophoresis (data are not shown). Multiplexed RT-PCR conditions were established in a series of preliminary experiments (data not shown). Finally, multiplexed nested RT-PCRs were executed with each viral target using 22 pairs of specific SAMRS-AEGIS primers and AEGIS external primers (Table 2). PCR amplicons generated under optimized conditions were visualized on ethidium bromide gel as clearly resolved bands of the expected sizes ranging from 59 to 160 base pairs (Table 5, Figure 3A). The PCR negative control showed non- substantial level of primer-dimerization.

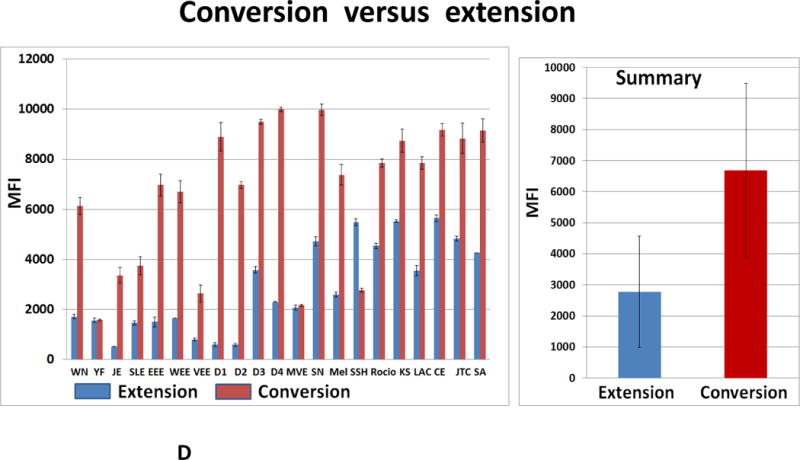

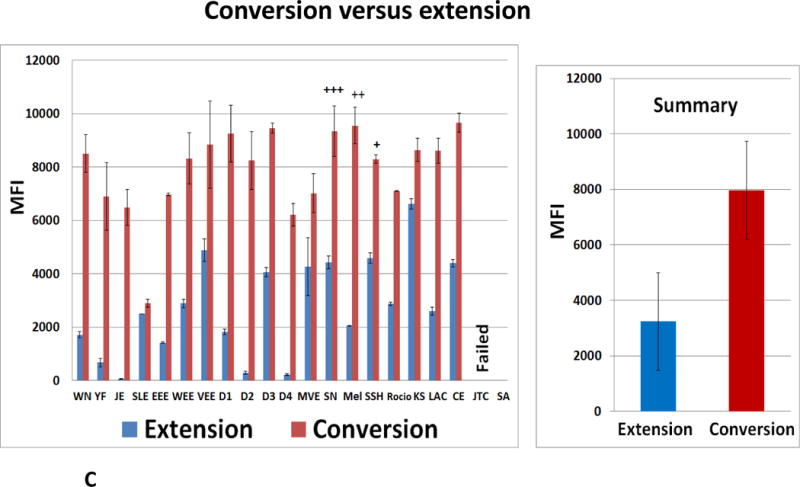

Figure 3.

(A) 55 cycles of 22-fold multiplexed nested RT-PCRs were executed with SAMRS-AEGIS primers and viral RNA simulants. Aliquots of the reaction mixture (4 μL of each 20 μL) were loaded on a 2.5 % TBE gel and vizualized by the ethidium bromide staining; prim- negative control (primers only); Luminex direct hybridization assays (DHA) were performed with AGTC (B) or AGTZ. (C) Amplicons generated by 22-fold multiplexed nested SAMRS-AEGIS RT-PCRs and extension or “dC-to-dZ” conversion reactions with external reverse biotinylated AEGIS primer. Samples were undiluted PCR products. Background, negative control, sample buffer was added to the Luminex mixture; B, C, the lowest panel indicates viral targets and Luminex beads identities. (D) Luminex profiles of standard (AGTC, extension, blue bars) versus AEGIS (AGTZ, conversion, red bars) amplicons, products of 22-fold multiplexed nested AEGIS-SAMRS RT-PCR, from the left, and summary, from the right. The average of the three independent experiments is presented. MFI, median fluorescence intensity (mean ± standard deviation). The viruses were (Table 5 for abbreviations) (B, C, D): WN, YF, JE, SLE, EEE, WEE, VEE, D1-D4, MVE, SN, Mel, SSH, Racio, KS, LAC, CE, JTC, SA, ChV, Primers control.

Amplicons containing only standard nucleotides were also produced by multiplexed one-step RT-PCRs and analyzed by agarose-gel electrophoresis (Figure 4A). The 22-fold multiplexed reactions were primed with full set of target-specific primers, each at the final concentration of 0.4 μM. The standard PCR amplicons were visualized on the ethidium bromide gel as clearly resolved bands of the expected sizes (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

(A) 35 cycles of conventional 22-fold multiplexed RT-PCRs were executed with standard nucleotides primers and RNA simulants. Aliquots of the reaction mixture (4 μL of each 20 μL) were loaded on a 2.5 % TBE gel and vizualized by the ethidium bromide; Luminex DHAs were performed with AGTZ (B,C) or AGTC (C) amplicons generated by 21-fold multiplexed conventional standard RT-PCR and extension or “dC-to-dZ” conversion reactions with all reverse biotinylated primers. (B) The bottom panel indicates viral targets and Luminex beads identities. (C) Luminex MFI profiles of standard (AGTC, extension, blue bars) versus AEGIS (AGTZ, conversion, red bars) amplicons, products of 21-fold multiplexed conventional standard RT-PCR, (from the left) and Summary, from the right. The average of the three independent experiments is presented. MFI, median fluorescence intensity, (mean± standard deviation); +, ++, +++, indicate false-positive fluorescent signals (one-three correspondingly). Viral assays order (B, C): WN, YF, JE, SLE, EEE, WEE, VEE, D1-D4, MVE, SN, Mel, SSH, Racio, KS, LAC, CE, JTC, SA, Primers control.

3.2. Validation of biotinylated PCR-amplicons on 22-fold multiplexed xMAP Luminex DHA platform

The identity of the target-specific biotinylated RT-PCR products were confirmed by the bead-based multiplexed Luminex xMAP direct hybridization assay. This was able to support a high throughput, simultaneous detection of multiple targets in a single molecular test.

Virus-specific asymmetric amplicons were obtained in two steps. First, 22-fold multiplexed nested SAMRS-AEGIS was set up in parallel with a standard conventional one-step RT-PCRs. Next, the extension without or with conversion was performed (Figure 2). Final products from the both sets of reactions (SAMRS-AEGIS RT-PCR followed by the extension/conversion and the standard RT-PCR followed by the extension/conversion) produced artificial AEGIS (AGTZ) and standard (AGTC) amplicons. AGTZ and AGTC amplicons were hybridized one at a time to a set of 22 target-specific AEGIS (APTC) or standard (AGTC) probes respectively, each immobilized to a unique microsphere population, analyzed by the Luminex-200 instrument, and expressed as median fluorescence intensity (MFI) units (Figures 3–6). The samples were undiluted PCR products. The “background” wells contained sample buffer.

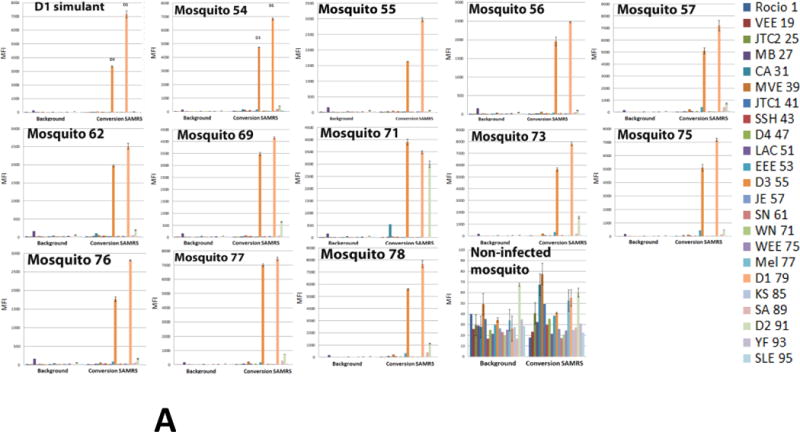

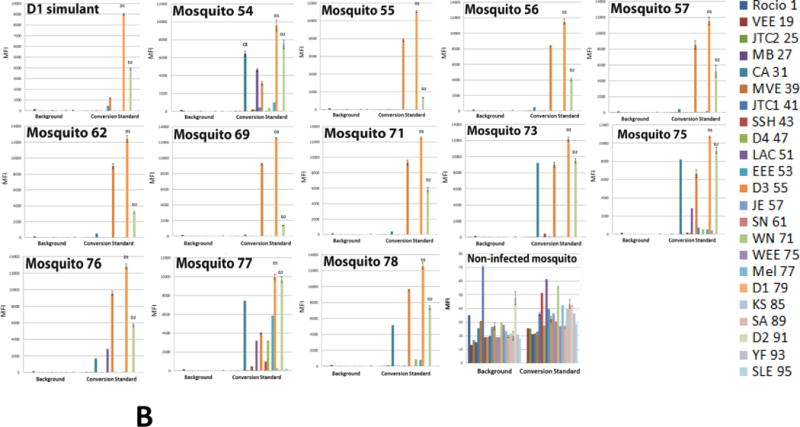

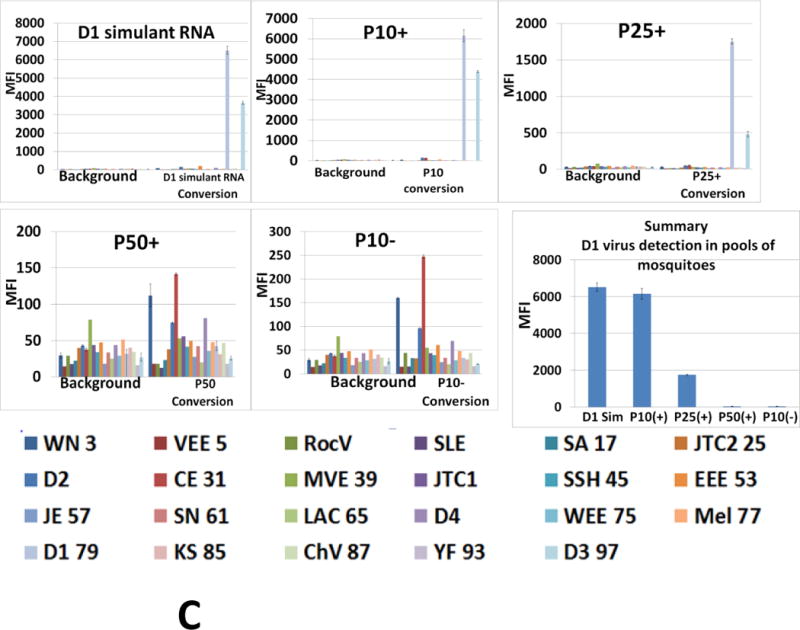

Figure 6.

Detection of dengue 1 Key West virus in infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes by multiplexed Luminex assay. (A) Assays were executed with PCR-amplicons generated by 22-fold multiplexed SAMRS RT-PCRs and “dC-to-dZ” conversion reactions, or (B) by 22-fold multiplexed standard RT-PCRs followed by “dC-to-dZ” conversion PCRs. Ten non-infected Aedes aegypti and 10 non-infected Aedes albopictus mosquitoes were analyzed as the “non-infected mosquito” negative control and representative data are shown; dengue 1 serotype virus RNA simulant was a positive control (A,B). The order of the infected mosquitos’ and controls in the assays panel (A, B): Dengue1 simulant (positive control), 54–57, 62, 69, 71, 73, 75–78, “non-infected mosquito” (negative control). (C) NA from one infected mosquito on the background of NA from 10, 25 or 50 non-infected mosquito’s pools were analyzed by the panel(p10+, p25+p50+); (p10-), NA isolated from pool of 10 non-infected mosquitoes represents the negative control; last panel from the right presents a summary of D1 virus detection. MFI, median fluorescence intensity. The panel from the right (A,B) or on the bottom (C) indicates viral targets and Luminex beads identities.

Negative controls, “primers”, were executed with all PCR components and primers. Assays were considered specific and positive if their ‘true match’ MFI were > 5 times background and the negative PCR control, and no nonspecific hybridization resulted in MFI > 20% of the true match. Luminex instrument hybridization temperature was evaluated in the pilot experiment and Luminex laser was set up at 55°C.

3.2.1. SAMRS/AEGIS RT-PCR amplicons validation

All the assays were positive in the presence of target RNA. Background fluorescence was low, in the range of 20 to 50 MFI units for all assays. Strong specific fluorescent signals were observed from each pair of amplicon/probe hybrids (AGTC/AGTC or AGTZ/ACTP), with signals in the 3,000- to 10,000-MFI-units range.

Interestingly, the MFI values observed with AEGIS amplicon/probe hybrids obtained after conversion were much higher than those observed with their standard (AGTC) counterparts. On average, the MFI values obtained for the AEGIS amplicon/probe hybrids were 2.3 times higher than from the comparable standard samples (Figures 3D). For certain targets, such as dengue serotypes 1 and 2, the MFI values registered for AGTZ amplicons were 12–13 times higher than for their AGTC counterparts. This observation is perhaps best explained by the fact that dZ:dP pairs contribute more to duplex stability than conventional dC:dG pairs.

Dengue serotypes 1 and 3 showed substantial cross-hybridization. The values of nonspecific MFI observed from the dengue serotypes 1 and 3 AGTZ amplicons/TCAP probes pairs were 65–90% of the specific fluorescent signal. The same patterns were found for their standard counterparts (extension reaction products), but MFI values were <30%. Due to the high sequence similarity between dengue serotypes viruses, the probes designed for dengue 1 and 3 are also similar (dengue 1 probe, CGAGAAACCGCGTGTCAACT, and Dengue 3 probe, AGAAACCGTGTGTCAACTCT), mainly differing by just one nucleotide (C–T) in the middle of the sequences and each possesses two additional nucleotide from 5′-end (dengue 1 probe) or from 3′-end (dengue3 probe). This makes absolute discrimination difficult under the common hybridization conditions established for 22 targets. Unexpected cross-hybridization was also registered for some viruses from the California serogroup (KS, CE, JTC2, and CE). The non-specific fluorescent signals’ values in general were 10–20% of specific. The MFI values of the negative samples (Figure 3B and C, panel “primers control”) were at background or slightly higher.

3.2.2. Standard RT-PCR amplicon validation

The products of standard 22-fold multiplexed RT-PCRs and conversion reactions, AGTZ amplicons, extended by the entire set of 5′-biotinylated Reverse target-specific primers were evaluated by Luminex DHAs (Figure 4B). Assays were positive for the most targets of Flavivirus and Alphavirus viral groups, as strong and only specific fluorescent signal in the range from 2,000 to 10,000 of the MFI units were registered. Dengue viruses’ profiles had the same patterns as already described (3.2.1.). The detection of SN and SA (Bunyaviridae/Orthobunyavirus) failed as the specific signals were absent and only false positive signals from the close-related targets of the California serogroup were registered. SN, Mel and SSH targets generated the strong positive signals, but strong false-positive signals (20–50% of specific) were also observed (Figure 4B). The MFI value produced by the negative control (Figure 4B, panel “primers only”) was much higher than the Background level (3,000 and 20–60 of MFI units respectively).

Positive fluorescent signals obtained for the standard amplicons, products of extension reactions, were significantly lower than registered from their AGTZ counterparts (Figure 4C).

The nested standard RT-PCRs were also executed with viral RNA simulants, with the final standard (not AEGIS) AGTC amplicons quantitated by Luminex DHAs (data are not shown). Only 8 samples were found to be positive, with the Luminex instrument detecting strong fluorescent target specific signals (Flavivirus and Alphavirus viral groups). The remaining assays failed to produce any signal, or produced strong false-positive signals.

In general, MFI values obtained for the AEGIS amplicon/probe hybrids were much higher than their standard counterparts profiles (Figure 4C). Again, this is consistent with the fact that Z:P pairs contribute more to duplex stability than standard C:G pairs.

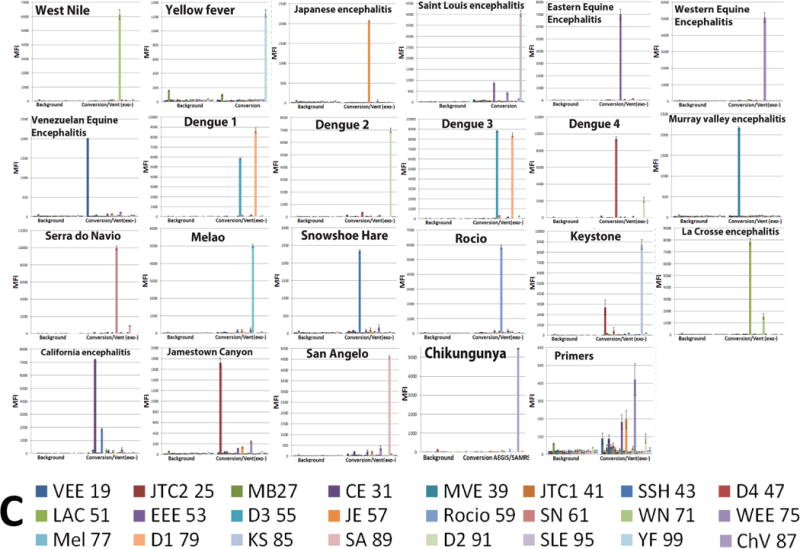

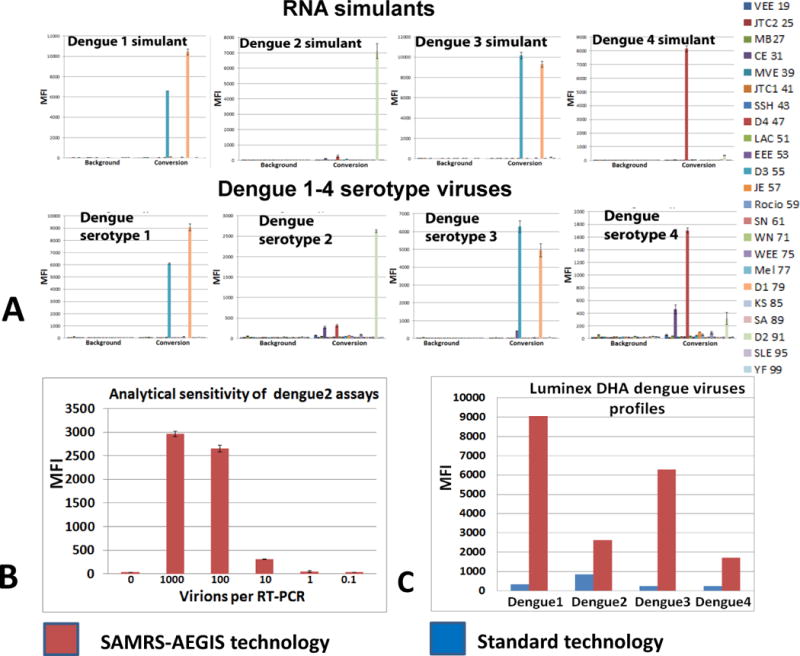

3.3. Diagnostic assays panel had been tested on full genome dengue viruses

3.3.1. Evaluation of dengue viruses

The performance and sensitivity of the diagnostic panel was evaluated against full genomic dengue viruses, serotype 1–4 (Figure 5). The viral stocks were titrated by plaque assays and their concentrations were expressed in plague forming units per mL (PFU/mL) (Table 3). However, the ratio between infectious units and viral RNA copies depends on the fraction of noninfectious RNA-containing virus, as defective interfering particles will differ between various viruses or stocks of the same virus. Therefore, PFU do not provide precise information on the concentration of RNA genomes in a virus stock. These uncertainties were circumvented by determining the titer of dengue 1–4 viral genomes using TaqMan real-time PCR. The ratio of physical to viable virions (PFU) was on average 1: 100.

Figure 5.

Detection of dengue serotypes viruses by multiplexed Luminex assays panel. Assays were executed with AGTZ amplicons, generated by 22-fold multiplexed SAMRS-AEGIS nested RT-PCR and “dC-to-dZ” conversion reactions (A,B,C,) or with AGTC amplicons, generated by 22-fold multiplexed standard RT-PCR and extension reaction (C). MFI, median fluorescence intensity. (A) dengue RNAs’ simulants and dengue serotypes 1–4 viruses; the panel from the right indicates dengue 1–4 viruses and Luminex beads identities; (B) the limit of serotype 2 dengue virus detection; (C) SAMRS/AEGIS technology versus standard conventional technology. Viral assays order (A): D1, D2, D3, D4.

Multiplexed RT-PCRs were optimized in series of preliminary experiments. One–step RT-PCRs were executed with viral RNAs under established conditions, except that the reverse transcription reaction temperature was decreased to 50°C. The amounts of viral RNAs equivalent to 20 virions/μL were taking into multiplexed nested SAMRS-AEGIS or standard conventional RT-PCRs. Four dengue virus serotypes were tested in triplicate, included four dengue RNA simulants as positive controls. Each of four dengue viral serotypes assays generated target-specific fluorescent signal and these Luminex DHA results agreed with the original findings (Figure 5A). The biotinylated amplicons of dengue 1 virus revealed substantial level of cross-hybridization with dengue 3 probe, the same pattern of Luminex profile was confirmed for dengue 1 RNA simulant (Figure 5A).

The analytical sensitivity of the dengue virus serotype assays was validated by comparison with standard conventional RT-PCR and Luminex technology (Figure 5C). All four viral assays produced 2.5–10 fold higher specific Luminex fluorescent signals when conversion technology was applied (Figure 5C). To infer the detection limit of the diagnostic panel, serial dilutions of dengue 2 RNA (10–1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, and 10−5) were tested. Dengue 2 viral titer, reported in infectious units, was 2×104 pfu/mL. This was corresponding to 2×106 virions/mL according to the TaqMan PCR data. Multiplexed nested SAMRS-AEGIS RT-PCRs, followed by conversion, was executed with each dilution and final biotinylated AGTZ amplicons were analyzed by 22-plex Luminex DHAs. As revealed, the measuring capability of the assay is, at least, 10 virions per 20 μL (or 0.5 virions per 1 μL) of the initial input into RT-PCR (Figure 5B). The assays produced positive signals at dilutions were amplicons could no longer be resolved on agarose gels.

3.3.2. Evaluation of dengue 1 virus infected mosquitoes

The performance and sensitivity of the diagnostic panel were also evaluated using nucleic acid (NA) preparations from dengue 1 virus infected mosquitoes. One-step multiplexed SAMRS or standard RT-PCRs were executed with 12 RNA samples, each isolated from a single infected mosquito body. Ten RNA samples isolated from non-infected Aedes aegypti and 10 RNA samples from Aedes albopictus mosquitoes were analyzed also as the “non-infected mosquito” negative control.

Conventional RT-PCRs were executed with 22 pairs of target-specific SAMRS primers (final concentration 0.2 μM) followed by conversion reactions with all 22 reverse-biotinylated SAMRS target-specific primers (final concentration 0.2 μM). Nested format of SAMRS-AEGIS RT-PCR was also tested but the performance was low efficient that might be due to insufficient concentration of target-specific primers in reverse transcription reaction (0.025 μM) used on the large background of mosquito NA.

The amounts of viral genome equivalents in the RT-PCRs varied from 6.25 to 210 (Table 6). Samples were tested in triplicate and included dengue 1 RNA simulant as a positive control. All infected samples generated dengue 1 positive and dengue 3 false positives signals on Luminex instrument; these Luminex profiles corresponded to the dengue 1 RNA simulant pattern (Figure 6A). All non-infected mosquitoes’ samples (negative control) were at the background level. The representative data (“non-infected mosquito control”) are shown in Figure 6. The “limit of detection” (LOD) of the panel was ~ 6 virions equivalents per 20 μL of RT-PCR. These observations are in an agreement with LOD data obtained for dengue 2 virus (3.3.1.).

Table 6.

Dengue 1 viral particles in infected Aedes albopictus (54–57, 62, 69, 71, 73) and Aedes aegypti (75–78) mosquitoes’ samples per PCR

| Mosquito identity | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 62 | 69 | 71 | 73 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 |

| Virions per 20 μL RT-PCR | n/a | 210 | 40 | 20.1 | 89.5 | 78.1 | 100 | 7 | n/a | 22.9 | n/a | 6.25 |

The products of standard RT-PCRs followed by conversion reactions were also compared by Luminex DHA. All samples targeted by standard primers were dengue 1 positive, and dengue 2 and 3 false positive (Figure 6B). Strong false positive signals (up to 80% of the positive) from California encephalitis, La Crosse encephalitis and eastern equine encephalitis viruses were also registered (mosquitoes 54, 75–78). The cross-reactivity between dengue 1 and dengue 3 viruses was expected due to high similarity of these serotypes and, as a consequence, probes designed for these viruses also shared high similarity (3.2.1.), while the cross –reactivity between dengue 1 and 2 serotypes were not anticipated as these probes didn’t share any substantial similarity.

If dengue 1and 3 is detected, further fine serotypes discrimination can be done either with already published primers or second sets of in home designed dengue primers and probes (Table A3) (these primers/probe sets exhibited good resolution in experiments, data not shown).

3.3.3. Evaluation of single dengue 1 infected mosquito in the non-infected mosquito’s pools

To increase the nucleic acid background, pools of 10, 25 or 50 non-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes were collected and nucleic acid samples were prepared as described previously (2.11.). Aliquots (2 μL) of each sample from non-infected mosquitoes’ pools were combined with aliquots (2 μL) of infected mosquito sample (about 100 viral genome equivalents) and analyzed by the assay (3.3.2.). Samples (marked as p10+, p25+ or p50+) were tested in triplicate and included dengue 1 RNA simulant as the positive control, with nucleic acids isolated from pool of 10, 25 or 50 non-infected mosquitoes (p10-, p25- or p50-) serving as negative controls.

The P10+ and p25+ samples were dengue 1 positive and dengue 3 false positive what was in the agreement with Luminex profile for the dengue 1 RNA simulant (positive control). The MFI value registered for p10+ assay was 3.4-fold of that registered for p25+ (6200 versus 1800 MFI units). Sample p50+ was dengue 1 negative but unspecific signals were not observed. The pools of non-infected mosquitoes (negative controls) were slightly higher than the background level. All three negative controls have similar Luminex profiles, and representative data for one of three (p10-) is shown in Figure 6C.

4. Discussion

Multiplexed PCR-based assays often failed because multiple primers presented in high concentrations interact with each other, unless they are exquisitely designed. Non-specific interference of oligonucleotides (DNA and RNA) is also thought to limit further multiplexed PCR (Elnifro et al., 2000); these are always present in real biological samples. Interaction between primers can form artifacts, including primer-dimers and extension products of nonspecifically paired primers, often imperfectly matched. These non-specific reactions compete for and deplete limiting reagents, often leading to false negatives in nucleic acid-targeted assays. Indeed, low sensitivity has been observed in several conventional multiplexed PCRs, with convention nested PCR mitigating only some of these problems (Ellis et al., 1997; Cassinotti and Siegl, 1998; Read et al., 2001). Even if these pitfalls are avoided, different amplicons having different sequences can be differentially amplified.

Work in synthetic biology over the past two decades has generated several kinds of artificial DNA that prevent these problems. In this work, self-avoiding molecular recognition systems (SAMRS) built into primers and probes prevent these from interacting with each other, no matter how many are added to an assay. Artificially expanded genetic information systems (AEGIS) allow external primers in a nested PCR format to bind no where to any natural DNA, including (in this case) mosquito DNA. Finally, conversion of standard sequences in the amplicons into AEGIS sequences allows the amplicons to be efficiently and uniformly captured. While alternative approaches were possible for multiplexed detection (for example, chips or arrays), the high-throughput Multiplexed xMAP Luminex system is adequate to detect amplicons that might arise from one of 22 mosquito-borne arboviruses that might be encountered in a mosquito captured in the field.

The SAMRS-AEGIS combination delivered the performance that is needed to support surveillance, at least as the panel was developed using viral RNA simulants. To ensure a more challenging test, the performance and the sensitivities of the panel were also evaluated with full genomic dengue virus RNA of different serotypes, and with laboratory-infected Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. The panel was capable to identify all four dengue serotypes in viral samples and dengue 1 virus in the infected mosquito nucleic acid samples with detection limit of 6–10 virions in a single mosquito (Figures 5A and 6A). The capability of the panel was also tested on the progressively increased mosquito nucleic acid background (from pools of 10, 25 or 50 mosquitoes). The panel could identify the presence of a single infected mosquito in a pool of 10 or 25 non-infected mosquitoes; only when the background rose to 50 uninfected mosquitoes did the Luminex fluorescent signals approach the background, with dengue 1.

Overall, the RT-PCR followed by a nested PCR having AEGIS components in the external primers was highly sensitive, detecting less than a dozen viral molecules without generating false positives. SAMRS allowed a high level of multiplexing with very little primer optimization, and with little concern about the formation of primer dimers.

The Luminex bead-reader detected multiplexed PCR- amplicons generated by the SAMRS-AEGIS combination, where SAMRS is used for high multiplexing and AEGIS is used to suppress noise. Accordingly, very few false positives were observed.

Adding conversion to the AEGIS-SAMRS PCR placed AEGIS components into capture tags, allowing products synthesized by templating on amplicons to be captured efficiently and with no noise. These architectures inverted the standard Luminex xTAG architecture, placing a biotin on a primer rather than on any triphosphate. We have found the DNA polymerase [Vent (exo-), NEB], that accurately place Z opposite G in a reverse primer elongation. The final product is a Z-containing biotin-tagged GAZT amplicon that binds to no natural DNA with sequence information of the amplicon retained. It can be captured by a CTPA oligonucleotide attached to a Luminex bead. The inverted assay created linear dose-response curves, with conversion improving the ability of the Luminex instrument to detect PCR-amplicons, producing higher specific fluorescent signals without the possibility of competition from any natural oligonucleotides, even in complex biological samples.

Finally, the xMAP Luminex panel accurately discriminated 22 mosquito-borne arboviruses. The SAMRS-AEGIS-conversion technology was compared with RT-PCR and Luminex DHA technology that used neither the SAMRS nor the AEGIS nucleic acid analogs. PCR amplicons from viral RNA simulants were more specific and more accurate with the SAMRS-AEGIS amplification; the comparable assays with standard nucleotides only gave ca. 25% failure, either by the absence of a positive signal or by the presence of a falsely positive signal (Figures 4B and 4C). Further, the incorporation of the AEGIS dP nucleotides instead of standard dG nucleotides in molecular probes increased specific fluorescent signals 2–10 fold (Figures 3D and 4C).

The conventional PCR-amplification based Luminex technique was 2.5–8.5 fold less efficient when being compared to the innovative SAMRS-AEGIG architecture (Figure 5C). SAMRS components in primers significantly improved 22-fold multiplexed assays executed with infected mosquito’s NA samples (Figure 6A, B).

Dengue serotypes 1 and 3 viruses revealed substantial level of cross-hybridization due to their large similarity (Figure 5A). The final fine discrimination of these serotypes can be done either with a pair of common primers and serotype specific capture probes developed to target 3′-UTR (S.A. Benner and N. Sharma, unpublished) or published primers/probes. The measuring capability of the Luminex assays panel is, at least, 6–10 virions per 20 μL of the initial input into RT-PCR that could not be resolved on the agarose gels.

Because SAMRS primers do not interact with other SAMRS primers, new SAMRS primers can be added at will to increase the level of multiplexing. Accordingly, researchers are invited to contact the authors to obtain expanded or alternative primer sets; custom designed primer sets are also available commercially from Firebird Biomolecular Sciences LLC (www.firebirdbio.com).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We developed and evaluated a single-tube high-throughput xMAP Luminex assay panel based on PCR amplification that detects 22 mosquito-borne arboviruses relevant to public health in the U.S.

To develop this panel we employed our innovative strategy based on the unnatural DNA base pairs (SAMRS and AEGIS) that exhibit high fidelity and efficiency in PCR and Luminex microarray hybridization technology.

The panel is potent to differentiate between many closely-related viruses from the genera Flavivirus, Alphavirus and Orthobunyavirus as dengue, West Nile and Japanese encephalitis, or the California serological group viruses.

The performance and the sensitivity of the panel have been evaluated with full genomic dengue virus serotypes and laboratory infected mosquitoes.

Acknowledgments

Dengue-1 virus (GenBank accession no. JQ675358, originally isolated from a human infected in Key West, FL in 2010) was kindly provided by the Florida Department of Health Bureau of Laboratories. Dengue viruses 1–4 were kindly provided by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Arbovirus Reference Collection. We thank E. Buckner for providing us with mosquito specimens used in the virus assays, D. Bettinardi for assistance with some of the experiments using dengue viruses. This study was supported by DARPA under its ADEPT program (HR0011-11-2-0018) the NIAID (R01AI098616), Nucleic Acids Licensing LLC, and Firebird Biomolecular Sciences LLC (under a contract from the Office of the Secretary of Defense, W911NF-12-C-0059). The basic research allowing this project was funded by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency under its basic research program (HDTRA1-13-1-0004).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alto BW, Lounibos LP, Mores CN, Reiskind MH. Larval competition alters susceptibility of adult Aedes mosquitoes to dengue infection. Proc Biol Sci. 2008;275:463–471. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Sankoh O, Myers MF, George DB, Jaenisch T, Wint GR, Simmons CP, Scott TW, Farrar JJ, Hay SI. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brathwaite Dick O, San Martin JL, Montoya RH, del Diego J, Zambrano B, Dayan GH. The history of dengue outbreaks in the Americas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:584–593. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell GL, Hills SL, Fischer M, Jacobson JA, Hoke CH, Hombach JM, Marfin AA, Solomon T, Tsai TF, Tsu VD, Ginsburg AS. Estimated global incidence of Japanese encephalitis: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:766–774. 774A–774E. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.085233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassinotti P, Siegl G. A nested-PCR assay for the simultaneous amplification of HSV-1, HSV-2, and HCMV genomes in patients with presumed herpetic CNS infections. J Virol Methods. 1998;71:105–14. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease, C., Prevention. Locally acquired Dengue–Key West, Florida, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease, C., Prevention. Japanese encephalitis in two children–United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:276–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao DY, Davis BS, Chang GJ. Development of multiplex real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assays for detecting eight medically important flaviviruses in mosquitoes. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:584–589. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00842-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Morais Bronzoni RV, Baleotti FG, Ribeiro Nogueira RM, Nunes M, Moraes Figueiredo LT. Duplex reverse transcription-PCR followed by nested PCR assays for detection and identification of Brazilian alphaviruses and flaviviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:696–702. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.696-702.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douce RW, Freire D, Tello B, Vasquez GA. A case of yellow fever vaccine-associated viscerotropic disease in Ecuador. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:740–742. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas MW, Stephens DP, Burrow JN, Anstey NM, Talbot K, Currie BJ. Murray Valley encephalitis in an adult traveller complicated by long-term flaccid paralysis: case report and review of the literature. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:284–288. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar SA. Applications of Luminex xMAP technology for rapid, high-throughput multiplexed nucleic acid detection. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;363:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JS, Fleming DM, Zambon MC. Multiplex reverse transcription-PCR for surveillance of influenza A and B viruses in England and Wales in 1995 and 1996. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2076–82. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.8.2076-2082.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elnifro EM, Ashshi AM, Cooper RJ, Klapper PE. Multiplex PCR: optimization and application in diagnostic virology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:559–570. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.559-570.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh ND, McMenamy SS, Turell MJ, Lee JS. Multi-gene detection and identification of mosquito-borne RNA viruses using an oligonucleotide microarray. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013a;7:e2349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh ND, Petz LN, Melanson VR, McMenamy SS, Turell MJ, Long LS, Pisarcik SE, Kengluecha A, Jaichapor B, O’Guinn ML, Lee JS. Evaluation of a field-portable DNA microarray platform and nucleic acid amplification strategies for the detection of arboviruses, arthropods, and bloodmeals. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013b;88:245–53. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler DJ. The continuing spread of West Nile virus in the western hemisphere. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1039–46. doi: 10.1086/521911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills SL, Griggs AC, Fischer M. Japanese encephalitis in travelers from non-endemic countries, 1973–2008. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:930–6. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshika S, Chen F, Leal NA, Benner SA. Artificial genetic systems: self-avoiding DNA in PCR and multiplexed PCR. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:5554–7. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houng HS, Chung-Ming Chen R, Vaughn DW, Kanesa-thasan N. Development of a fluorogenic RT-PCR system for quantitative identification of dengue virus serotypes 1–4 using conserved and serotype-specific 3′ noncoding sequences. J Virol Methods. 2001;95:19–32. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(01)00280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentes ES, Poumerol G, Gershman MD, Hill DR, Lemarchand J, Lewis RF, Staples JE, Tomori O, Wilder-Smith A, Monath TP, Informal W. H. O. W. G. o. G. R. f. Y. F The revised global yellow fever risk map and recommendations for vaccination, 2010: consensus of the Informal WHO Working Group on Geographic Risk for Yellow Fever. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:622–32. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienzle N, Boyes L. Murray Valley encephalitis: case report and review of neuroradiological features. Australas Radiol. 2003;47:61–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.2003.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanciotti RS, Roehrig JT, Deubel V, Smith J, Parker M, Steele K, Crise B, Volpe KE, Crabtree MB, Scherret JH, Hall RA, MacKenzie JS, Cropp CB, Panigrahy B, Ostlund E, Schmitt B, Malkinson M, Banet C, Weissman J, Komar N, Savage HM, Stone W, McNamara T, Gubler DJ. Origin of the West Nile virus responsible for an outbreak of encephalitis in the northeastern United States. Science. 1999;286:2333–7. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KO, Rodriguez LF, Herrington E, Kharat V, Vasilakis N, Walker C, Turner C, Khuwaja S, Arafat R, Weaver SC, Martinez D, Kilborn C, Bueno R, Reyna M. Identification of dengue fever cases in Houston, Texas, with evidence of autochthonous transmission between 2003 and 2005. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13:835–45. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naze F, Le Roux K, Schuffenecker I, Zeller H, Staikowsky F, Grivard P, Michault A, Laurent P. Simultaneous detection and quantitation of Chikungunya, dengue and West Nile viruses by multiplex RT-PCR assays and dengue virus typing using high resolution melting. J Virol Methods. 2009;162:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAHO (Pan American Health Organization) 2014 Available at http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=9053&Itemid=39843 (Accessed June 11, 2014)

- Read SJ, Mitchell JL, Fink CG. LightCycler multiplex PCR for the laboratory diagnosis of common viral infections of the central nervous system. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3056–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3056-3059.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter P. Yellow fever and dengue: a threat to Europe? Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramozzino N, Crance JM, Jouan A, DeBriel DA, Stoll F, Garin D. Comparison of flavivirus universal primer pairs and development of a rapid, highly sensitive heminested reverse transcription-PCR assay for detection of flaviviruses targeted to a conserved region of the NS5 gene sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1922–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.5.1922-1927.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D, Richards SL, Alto BW, Bettinardi DJ, Smartt CT. Genome sequence analysis of dengue virus 1 isolated in key west, Florida. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim S, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. Molecular discrimination of mosquito vectors and their pathogens. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2009;9:757–65. doi: 10.1586/erm.09.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC, Reisen WK. Present and future arboviral threats. Antiviral Res. 2010;85:328–45. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhold B. Americas’ dengue escalation is real–and shifting. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:A 117. doi: 10.1289/ehp.118-a117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Takasaki T, Nawa M, Kurane I. Virus isolation as one of the diagnostic methods for dengue virus infection. J Clin Virol. 2002;24:203–9. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(01)00250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Chen F, Chamberlin SG, Benner SA. Expanded genetic alphabets in the polymerase chain reaction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:177–80. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Durante M, Glushakova LG, Sharma N, Leal NA, Bradley KM, Chen F, Benner SA. Conversion strategy using an expanded genetic alphabet to assay nucleic acids. Anal Chem. 2013;85:4705–12. doi: 10.1021/ac400422r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh JY, Lee JH, Seo HJ, Park JY, Moon JS, Cho IS, Lee JB, Park SY, Song CS, Choi IS. Fast duplex one-step reverse transcriptase PCR for rapid differential detection of West Nile and Japanese encephalitis viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4010–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00582-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.