Abstract

Nanomaterials are used in diverse fields including food, cosmetic, and medical industries. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NP) are widely used, but their effects on biological systems and mechanism of toxicity have not been elucidated fully. Here, we report the toxicological mechanism of TiO2-NP in cell organelles. Human bronchial epithelial cells (16HBE14o-) were exposed to 50 and 100 μg/mL TiO2-NP for 24 and 48 h. Our results showed that TiO2-NP induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in the cells and disrupted the mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAMs) and calcium ion balance, thereby increasing autophagy. In contrast, an inhibitor of ER stress, tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), mitigated the cellular toxic response, suggesting that TiO2-NP promoted toxicity via ER stress. This novel mechanism of TiO2-NP toxicity in human bronchial epithelial cells suggests that further exhaustive research on the harmful effects of these nanoparticles in relevant organisms is needed for their safe application.

Introduction

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NP) have widespread applications in various fields and are used in sunscreens, cosmetics, food products, toothpastes, and medical reagents [1–4]. In recent years, many studies have focused on the biomedical application of TiO2-NP in areas such as cancer therapy, drug delivery systems, cell imaging, genetic engineering, biosensors, and biological experiments [5–7].

However, with the increasing developments in the application of TiO2-NP, concerns regarding their toxicity to humans also increase. Many studies have reported that TiO2-NP elicit a toxic response in in vitro and in vivo systems. Bhattacharya et al. reported that TiO2-NP of <100 nm in diameter were able to generate free radicals and elevate DNA adduct formation (8-OHdG) in human lung fibroblasts [8]. In addition, in A549 cells, the anatase TiO2-NP induced mitochondrial injury in a dose-dependent manner owing to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation [9]. Oesch and Landsiedel reviewed the genotoxicity of TiO2-NP using various test results [10]. Moreover, Sager et al. reported that P-25 TiO2-NP suspension (anatase: rutile = 80:20, 21 nm) induces an inflammation response in rats [11]. Oberdorster et al. [12] reported a similar result that 21-nm TiO2-NP had inflammatory effects on the alveolar interstitium in the lungs. Ferin et al. detected polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes in lavage cells in rat lung after inhalation of ~20-nm TiO2-NP [13]. Although there are many toxicity results, the detailed molecular mechanism of TiO2-NP toxicity is not clear.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an organelle that regulates protein secretion, cell surface development, and maintenance of the calcium ion (Ca2+) concentration of cells [4]. Thus, disruption of ER homeostasis leads to protein misfolding and ER stress, which affect both the quality control and translation of protein. The membranes of the ER and mitochondria are enriched with Ca2+-binding chaperones called mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs), which preserve and regulate cellular homeostasis in different environments [14]. Studies have shown that ER stress is linked closely to changes in the composition of MAMs, deregulated Ca2+ transport, and cell death [15]. Furthermore, ER stress is associated with protein degradation via autophagy, which at abnormal levels, leads to cytotoxic processing or mechanisms such as apoptosis [16].

In this study, we demonstrated that ER stress-mediated MAM disruption, autophagy, and mitochondrial dysfunction might play a key role in the TiO2-NP-induced toxic responses in human bronchial epithelial cells.

Materials and Methods

Characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles

The TiO2 nanoparticles (TiO2-NP, P-25; anatase:rutile, 8:2) were purchased from Degussa Korea (Inchon, Korea). The structure and morphology of the TiO2-NP were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. The TEM samples were dispersed in methanol, and a drop of the suspension was placed on formvar-carbon film on a square 300-mesh copper grid, followed by drying the grid at room temperature for 1 h. We conducted X-ray diffraction (XRD) using the X’pert PW1827 diffractometer (Philips, Netherlands) to confirm the crystal structure of the TiO2-NP [17]. The goniometer was motorized and moved through a scanning range of θ–2θ. The diffractometer was operated at 40 kV and 40 mA in the range of 20–80°. The steps were performed in increments of 0.05°, and counts were collected for 5 s at each step [18]. For dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements, 4 mL of a 0.2 mg/mL suspension of TiO2-NPs in distilled water was sonicated for 30 s. The hydrodynamic sizes and zeta potentials of the particle suspension were measured at room temperature using an Electrophoretic Light Scattering Spectrophotometer (ELS-8000, Photal, Osaka, Japan), with an accumulation time of 70 times and an equilibration time of 60 s.

Suspension of TiO2 nanoparticles

We chose a suspension protocol that has been proven to yield the best dispersion of the nanomaterials in previous research [19]. For suspension in culture medium, TiO2-NP powder was dispersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 10 mg/mL and sonicated for 10 min using an Ultrasonic cleaner (5510-DTH, Branson, MI, USA). After sonication, to prepare the end-point concentrations, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)-F12 medium (Gibco, NY, USA) was transferred to test tubes and diluted with the TiO2-NP stock solution.

Cell culture and viability assay

The human bronchial epithelial cells (16HBE14o-) were a gift from Dr. Dieter Gruenert (University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA). The cells were incubated in DMEM-F12 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cell viability and proliferation were determined following treatment with TiO2-NP using the xCELLigence RTCA DP system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), which monitors cellular events in real-time without incorporated labels [17]. Briefly, cells (0.5 × 103) were seeded in each chamber of an E-plate. After an overnight incubation, cells were treated with 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL TiO2-NPs and monitored for 72 h. This system observes electrical impedance across interdigitated microelectrodes that are integrated on the bottom of the E-plate. The detection of impedance provides quantitative results about the cell number, proliferation, and viability. To measure the potential effects of TiO2-NP on cells, xCELLigence RTCA DP system-based cell viability assay was performed. Briefly, after seeding the cells (0.5x104) in 96-well plates, MTT assay using the reagent MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] (Sigma, MA, USA) and WST-1 assay using reagent WST-1 [2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) were performed after 24h and 48h of TiO2-NP treatment. All experiments were repeated three times.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

The generation of ROS in the cells following TiO2-NP treatment was determined using 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2-DCFDA), an indicator of intracellular ROS [20]. The process involves elimination of the acetate groups (non-fluorescent) by intracellular esterases with the generation of oxidation in the cells [21]. H2-DCFDA stock solution (10 mM) in DMSO was diluted in medium to attain a 5 μM working concentration. After incubation for 1 h, the cells were rinsed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. The fluorescence was detected using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM710, Carl Zeiss, Germany) and fluorescence-activated cells sorting (FACS, BD Bioscience, New Jersey, USA) [17].

Western blot assay

After homogenization of the cells, the protein concentration was measured using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). Protein (25 μg) was loaded into the wells, separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels (10–15%) (80 V, 3 h), and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (50 V, 2 h). After membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk for 1 h, immunoblotting was conducted by incubating with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. In this study, 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (Grp78), binding immunoglobulin protein (Bip), inositol-requiring protein 1 (IRE-1), phospho-IRE-1α, C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), and microtubule-associated protein-1 light-chain 3 (LC3) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (MA, USA). Sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1, p62), voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 (VDAC1), and beclin-1 (BECN1) antibodies were purchased from Abcam (MA, USA). Actin and 75 kDa glucose regulated protein (Grp75) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz (CA, USA). After incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature and washing, the bands of interest were measured using an ATTO CS image analyzer 3.0 (ATTO Corp., Tokyo, Japan) [17].

Immunofluorescence staining

The TiO2-NP-treated cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min and then treated with 1% Triton X-100 for 15 min. After fixation, the samples were washed and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in 1× tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 1 h at 37°C. After washing, samples were incubated overnight with the primary antibodies (IP3R, VDAC, and LC3) diluted 1:200 in blocking solution. After washing with 1× Tween 20-TBS, the fluorescence of the HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies was measured (Invitrogen, CA, USA). After rinsing, samples were mounted with DAKO Cytomation Faramount Aqueous Mounting solution (DAKO, CA, USA) and imaged using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM, LSM710, Carl Zeiss, Germany) [17]. The stained LC3-fluorescent puncta were counted using the Image J program supported by National Institutes of Health (MD, USA).

Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) analysis of cellular organelles

The TiO2-NP-treated cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde with 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) buffer at 4°C for 6 h. The fixed cells were dehydrated in serially diluted ethanol (30, 50, 70, 80, 90, and 100%). After dehydration, the samples were infiltrated with a 1:1 mixture of propylene oxide and epon at 70°C overnight. Ultrathin sections (about 50 mm) were sliced, mounted on a copper grid, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and monitored using a JEM 1010 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) [17].

Rhod-2 AM staining

Cells (1.0 × 104 cells/well) were seeded on 8-well chamber slides (Nalge Nunc, NY, USA) and incubated for 24 or 48 h with 50 or 100 μg/mL TiO2-NP. After incubation, the cells were rinsed with 1 × PBS and incubated with 10 μM Rhod-2 AM ester (Biotium, CA, USA) in PBS for 30 min at 37°C. After 30 min, the cells were washed and fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min at room temperature. The slides were monitored using CLSM (Carl Zeiss, Germany) [21].

Measurement of mitochondrial intensity and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels

After incubation of the cultures with TiO2-NP for 24 and 48 h, the mitochondrial intensity was detected by staining with 100 nM Mito-tracker (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The Mito tracker images were analyzed using the Mytoe program, which is software for analyzing mitochondrial dynamics from fluorescence microscope images [22]. To monitor the levels of ATP, normal lung cells were seeded on a 96-well plate and treated with TiO2-NP for 24 and 48 h, followed by incubation with 100 μL of CellTiter-Glo reagent (Promega, TN, USA) for 10 min. The luminescent signal was detected using a luminometer (Berthold, Germany).

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) with n = 3. The statistical analyses were carried out using one-way and two-way ANOVA. The differences were considered statically significant with p values of p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001.

Results

Characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles

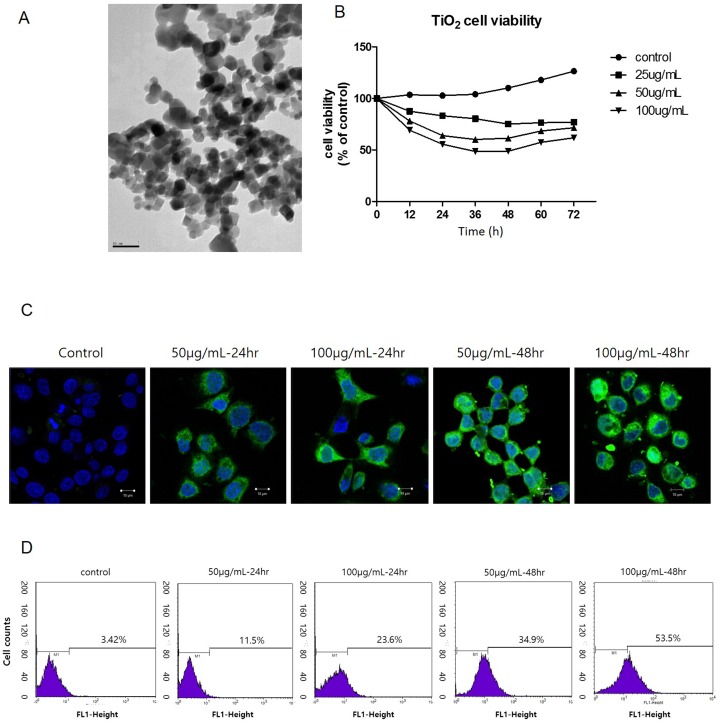

The particle shape and size of the TiO2-NP were analyzed using TEM (Fig 1A). In addition, the XRD pattern showed that the TiO2-NP contained a mixture of the anatase and rutile forms (S1 Fig). The hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of the TiO2-NP were determined using DLS. The TiO2-NP had an induced hydrodynamic size of approximately 250 nm in water or in medium, confirming that they are able to aggregate in suspension. The zeta potential results showed that the TiO2-NP had negatively charged surfaces in the medium (Table 1). Zeta potential values that are greater than +25 or less than −25 mV typically indicate good stability [23]. Therefore, the zeta potential of TiO2-NP in water or medium indicated that the TiO2-NP were aggregated in suspension. To investigate the cellular effects of the TiO2-NP, cell proliferation and viability were determined during 72 h in real time using the xCELLigence system. The real-time viability of TiO2-NP-treated cells was decreased as a function of TiO2-NP concentration and time (Fig 1B). We also confirmed this result using the MTT and WST-1 assays. As shown Fig B in S2 Fig, the almost identical cell viability results were obtained from both assays. To evaluate the intracellular ROS generation and elevation induced by TiO2-NP, we performed H2-DCFDA staining and FACS detection of cells treated with TiO2-NP for 24 and 48 h. CLSM images revealed that the fluorescence intensity was proportional to the increased treatment time and concentration of TiO2-NP (Fig 1C and Fig A in S2 Fig). According to the FACS data, the H2-DCFDA fluorescence increased in TiO2-NP treated cells (Fig 1D). Further, the number of stained cells increased in the TiO2-NP-treated cells. Our results show that TiO2-NP is able to generate intracellular ROS in human bronchial epithelial cells.

Fig 1. Characterization of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NP) and detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in human bronchial epithelial cells.

(A) TEM image of TiO2-NP shape and size. (B) During exposure of 16HBE14o- cells to TiO2-NP, viability and proliferation of cells were monitored in real-time using the xCELLigence system for 72 h. (C) To confirm the generation of ROS after TiO2-NP treatment, H2-DCFDA staining was performed in cells. The green fluorescence signal was induced gradually (scale bar, 10 μm; magnification, 400×). (D) To quantify the intensity of the green fluorescence, FACS analysis was performed. TEM, transmission electron microscopy; H2-DCFDA, 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Table 1. Physical characterization of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NP).

| Hydrodynamic diameter (nm) | Zeta potential (mV) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distilled water | Medium | Distilled water | Medium | |

| TiO2-NP | 220.4 | 295.9 | 19.29 | -26.01 |

TiO2 nanoparticles induce ER stress in normal human lung cells

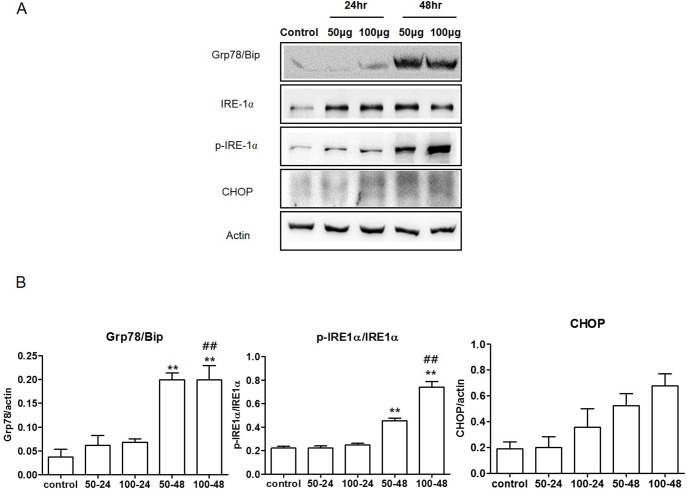

To determine the ER stress response in cells following TiO2-NP treatment, we incubated human bronchial epithelial cells with various doses of TiO2-NP at different time points. The expression of the ER stress-related proteins, including Grp78/Bip, IRE-1α, phospho-IRE-1α, and CHOP, were analyzed by western blot. The results indicated that the expression levels of these proteins increased in TiO2-NP-treated cells. The results indicated that the expression levels of these proteins were increased in TiO2-NP-treated cells as determined by densitometric analysis (Fig 2A). These results showed that TiO2-NP exposure increases ER stress in cells. Phosphorylation of the IRE-1α protein is reported to be a marker of its activation [24]. Therefore, we calculated the ratio of phosphorylated IRE-1α to total IRE-1α. In cells treated with 100 μg/mL TiO2-NP for 48 h, the IRE-1α phosphorylation significantly increased. Calnexin is an integral protein of the ER, which is known to correlate with the condition of the ER [25]. Our results demonstrated that treatment with TiO2-NP decreased calnexin expression (Fig A and B in S3 Fig). These results show that TiO2-NP induce ER stress and affect the condition of the ER in human bronchial epithelial cells.

Fig 2. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NP) treatment elevates endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in human bronchial epithelial cells.

(A) To detect the induction of ER stress after TiO2-NP treatment, expression levels of Grp78/Bip, IRE-1α, phospho-IRE-1α, and CHOP were detected using western blot analysis. (B) Each bar represents the mean ± SEM, n = 3, **p < 0.01 (comparison between TiO2-NP concentrations, 50 and 100 μg), ## p < 0.01 (comparison between TiO2-NP treatment times, 24 and 48 h). Grp78, 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein; Bip, binding immunoglobulin protein; phosphorylated inositol-requiring protein 1 (phospho-IRE-1 α); CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein.

TiO2 nanoparticles disrupt mitochondria by damaging MAMs and cellular calcium homeostasis

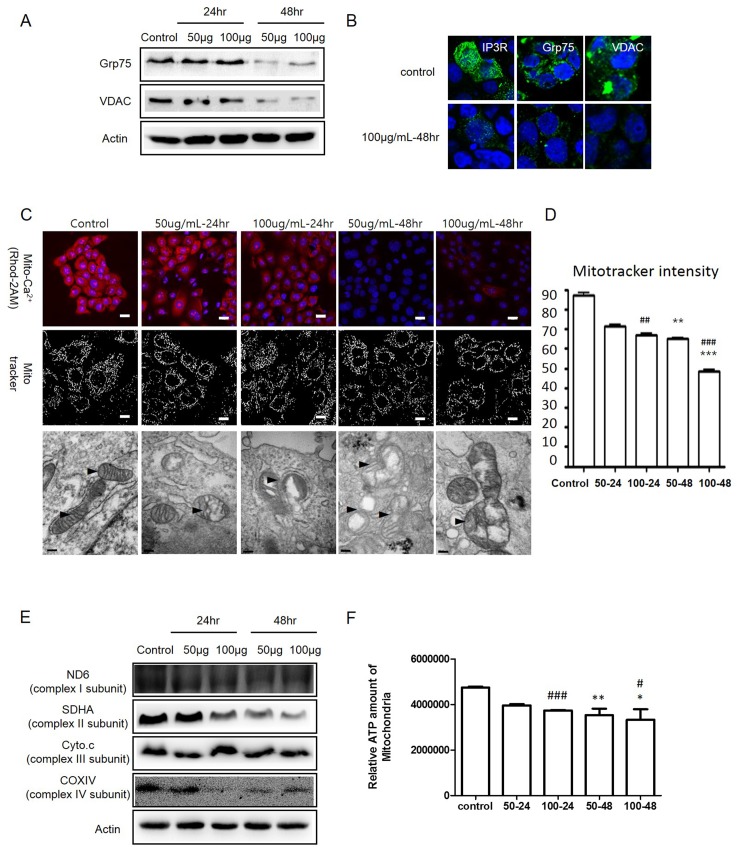

Disruption of calcium homeostasis is related directly to the induction of ER stress [26]. To investigate Ca2+ homeostasis following TiO2-NP treatment, the integrity of mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs), which regulate the Ca2+ flow between the ER and mitochondria, was evaluated. Disruption of MAMs was detected by measuring the expression levels of several cellular Ca2+-regulating proteins such as inositol triphosphate receptor (IP3R; a glycoprotein complex in the ER membrane), voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 (VDAC1; outer mitochondrial membrane protein that mediates Ca2+ flow), and 75-kDa glucose regulated protein (Grp75; a heat shock 70 family protein that regulates both IP3R and VDAC1) (Fig 3A and 3B and S4 Fig). To determine the quantitative changes in mitochondrial Ca2+ levels, cells were stained with Rhod-2 AM, a mitochondrial Ca2+ indicator. CLSM images revealed that the fluorescence decreased in TiO2-NP-treated cells. (Fig 3C, upper panel).

Fig 3. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NP) damage the connection between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria.

(A) To detect disruption of the mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs), proteins related to MAMs (Grp75 and VDAC) were detected using western blot analysis. (B) Immunofluorescence assay of IP3R, Grp75, and VDAC between the control and 100 μg/mL TiO2-NP treatment groups for 48 h. (Green, IP3R, Grp75, and VDAC; Blue, DAPI-Nucleus). (C) Upper panel, Ca2+ in the mitochondria was stained by Rhod-2 AM; middle panel, mitochondria staining with Mito tracker; bottom panel, TEM image of mitochondria after TiO2-NP treatment. (D) Mito tracker fluorescence of interest was analyzed further by the Mytoe program. Each bar represents mean ± SEM, n = 5. Significant differences are indicated by **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (comparison between TiO2-NP treatment concentrations, 50 and 100 μg) and ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 (comparison between TiO2-NP treatment time, 24 and 48 h). (E) To detect mitochondria dysfunction, the proteins related to the respiration chain in the mitochondria, including ND6 (complex subunit I), SDHA (complex subunit II), Cyto c (complex subunit III), and COXIV (complex subunit IV), were analyzed using western blot assay. (F) ATP levels in the mitochondria after treatment with TiO2-NP. Significant differences are indicated by *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (comparison between TiO2-NP treatment concentrations, 50 and 100 μg) and # p < 0.05, ### p < 0.001 (comparison between TiO2-NP treatment times, 24 and 48 h). IP3R, inositol triphosphate receptor; VDAC1, voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1; Grp75, 75 kDa glucose regulated protein; ND6, NADH dehydrogenase; SDHA, succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit A; Cyto C, cytochrome C; COXIV, cyto C oxidase IV.

Changes in the mitochondrial status also were assessed using CLSM imaging with the Mito-tracker staining and TEM imaging. The Mito-tracker staining images showed that the mitochondria morphology was altered by TiO2-NP treatment; the alterations of the mitochondria were digitalized by the Mytoe program (Fig 3C, middle panel and Fig 3D). The Mytoe analysis revealed that the intensity of the Mito tracker staining decreased significantly in TiO2-NP-treated cells (Fig 3D). The TEM images also clearly demonstrated morphological changes in the mitochondria, such as swelling and disruption of the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes (Fig 3C, bottom panel). To determine the disruption of mitochondrial function, we measured the expression levels of the respiration chain-related proteins, NADH dehydrogenase (ND6, complex subunit I), succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit A (complex subunit II, SDHA), cytochrome C (Cyto C, complex subunit III), and cyto C oxidase IV (COX 1V, complex IV subunit). The western blot results showed that the protein levels decreased in TiO2-NP-treated cells (Fig 3E). To monitor mitochondrial biogenesis, the ATP levels were measured after treatment of cells with TiO2-NP. The cellular ATP levels decreased significantly (Fig 3F). Our results show that induced ER stress could demolish MAMs and mitochondrial calcium homeostasis in cells. In addition, induced ER stress could disrupt mitochondrial morphology and biogenesis.

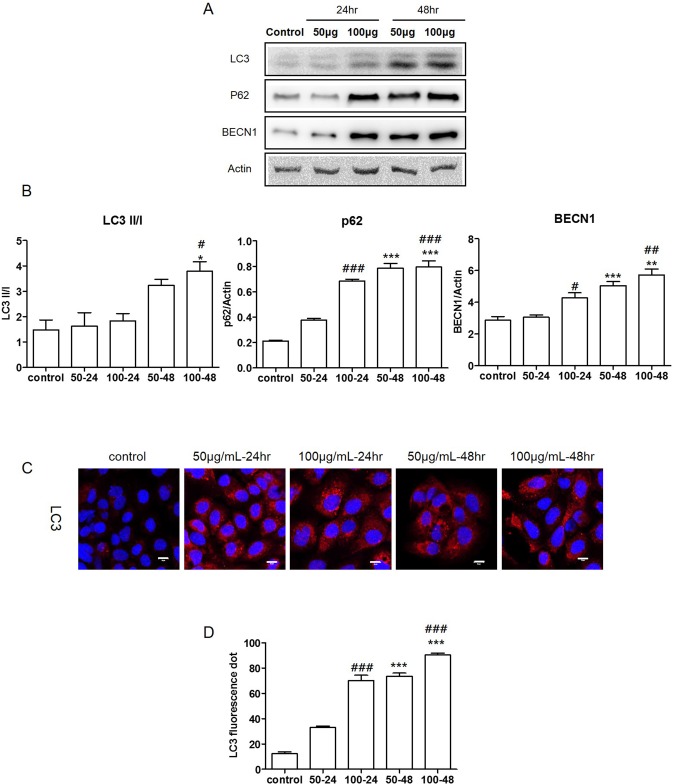

TiO2 nanoparticles induce autophagy in normal human lung cells

ER stress-induced autophagy correlates with cell death [27]. To determine if autophagy was induced in TiO2-NP-treated cells, the expression levels of LC3, sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1/p62), and BECN1 were examined by western blot assay and densitometric analysis. LC3 is one of the key regulators of autophagy, which is measured quantitatively by the ratio of LC3 II to LC3 I [28]. Our results showed that the LC3 II/LC3 I ratio increased significantly in the TiO2-NP-treated cells. Additionally, the expression of SQSTM1/p62 and BECN1 also increased significantly in the TiO2-NP-treated cells (Fig 4A and 4B). Furthermore, the immunofluorescence assay revealed that TiO2-NP treatment increased the number of LC3 fluorescence puncta (red) (Fig 4C). We counted the LC3 puncta using the Image J software (Fig 4D). Taken together, our results clearly demonstrate that the TiO2-NP induces autophagy in human bronchial epithelial cells.

Fig 4. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NP) induced autophagy in human bronchial epithelial cells.

(A) Expression levels of the autophagy related proteins LC3, p62, and BECN1 were determined by western blot assay. (B) Each bar represents the mean ± SEM, n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (comparison between TiO2-NP treatment concentrations, 50 and 100 μg), ## p < 0.01 and ### p < 0.001 (comparison between TiO2-NP treatment times, 24 and 48 h). (C) Immunofluorescence assay of LC3. (Red: LC3 and Blue: nucleus. Scale bar, 10 μm). (D) Increased numbers of red puncta and vacuoles counted in cells after TiO2-NP treatment. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM, n = 3, ***p < 0.001 (comparison between TiO2-NP treatment concentrations, 50 and 100 μg) ### p < 0.001 (comparison between TiO2-NP treatment times, 24 and 48 h). LC3, microtubule-associated protein-1 light-chain 3; SQSTM1, p62, Sequestosome 1; BECN1, beclin-1.

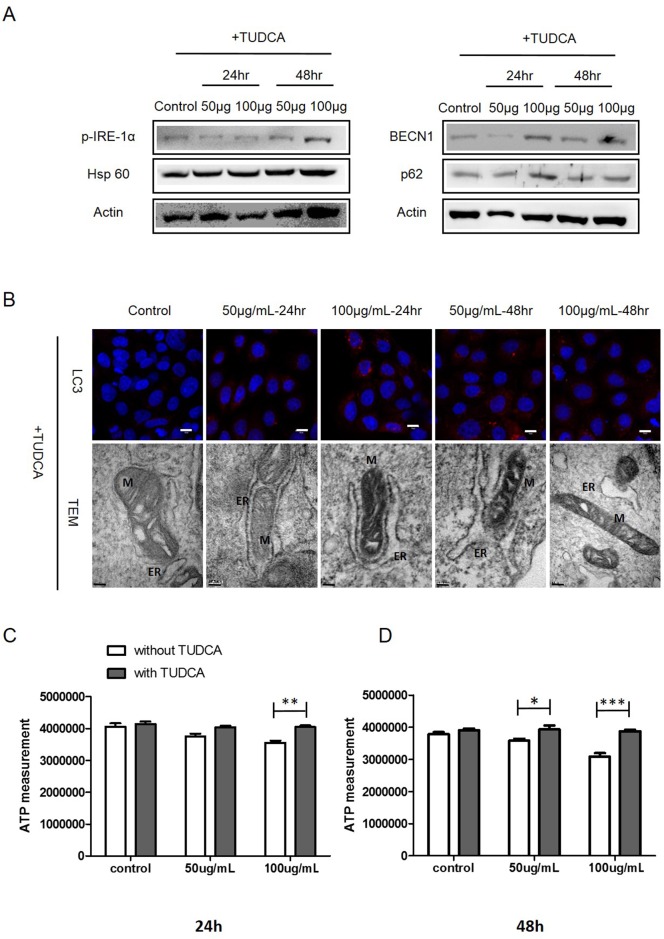

Inhibition of ER stress decreases TiO2 nanoparticles cytotoxicity

Tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) is a well-known inhibitor of ER stress [29]. To determine the potential effects of the inhibition of ER stress on mitochondria function disruption, autophagy, and cell toxicity, normal lung cells were treated with TUDCA (1mM) for 24h before exposure to TiO2-NP. Compared with the expression levels of actin, the internal standard, co-treatment with TiO2-NP and TUDCA did not induce any significant changes in the protein expression levels of phospho-IRE-1α, Hsp60, BECN, and p62 (Fig 5A). Furthermore, treatment with TUDCA and TiO2-NP did not cause any significant changes in the LC3 levels (Fig 5B). TEM images demonstrated no significant changes in the mitochondrial or ER morphology in cells pretreated with TUDCA (Fig 5B). To confirm whether ER stress is associated with the biogenesis of mitochondria, we compared the ATP levels of TiO2-NP-treated cells with TUDCA pretreatment with those without pretreatment. Our results indicated that TiO2-NP alone decreased ATP levels. However, TUDCA pretreatment prevented this effect (Fig 5C and 5D). The levels of ER marker, calnexin remained unaltered in TUDCA co-treated cells (S5 Fig). Together, our results indicate that the cells with blocked ER stress do not exhibit any autophagy and mitochondria disruption following treatment with TiO2-NP.

Fig 5. Treatment with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress inhibitor (TUDCA) affects cell biogenesis.

(A) Cells were treated with TUDCA followed by TiO2-NP, and then, western blot assay of p-IRE-1α, HSP60, BECN1, and p62 was performed. (B) LC3 levels were determined using immunofluorescence (scale bar, 10 μm). Mitochondria (M) and ER conditions were determined by TEM imaging. (C) Amount of ATP in cells after treatment with TiO2-NP with or without TUDCA for 24 h; ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *p<0.05 (2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's multiple comparison post-test), and (D) for 48 h (White bar, TiO2-NP only treatment; grey bar, TiO2-NP treatment with TUDCA). TUDCA, tauroursodeoxycholic acid; LC3, microtubule-associated protein-1 light-chain 3; HSP60, heat shock protein 60; p62, Sequestosome 1; BECN1, beclin-1; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Discussion

TiO2-NP are widely used owing to their unique characteristics, which include extended photostability, strong oxidizing energy, relatively low descriptive toxicity, and easy availability. Due to these properties, TiO2-NP are being used in diverse biomedical areas such as cell imaging, biosensors, genetic engineering in cancer therapy, drug delivery, and development of medical implants [5]. However, prior to its extensive use in humans, the mechanisms underlying the potential toxic effects of TiO2-NP should be carefully identified.

The ROS generated owing to nanomaterials, including metal oxide-based nanoparticles, TiO2-NP, carbon fullerenes, and carbon nanotubes, are associated closely with cell damage such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell organelle disruption [30–33]. Many studies have reported that TiO2-NP induce toxic response by increasing the generation of ROS, which disrupts redox homeostasis [34, 35]. Our H2-DCFDA staining data revealed the generation of ROS following TiO2-NP treatment in human bronchial epithelial cells (Fig 1 and S1 Fig). Therefore, we hypothesized that the elevated ROS levels affected the ER, which is one of the organelles that plays an important role in the cellular quality control systems and sensitivity to oxidative stress. In addition, this action may be a key mechanism of TiO2-NP toxicity. The ER is susceptible to diverse stressors such as misfolded proteins, environmental triggers, metabolic disturbances, and oxidative stress [36]. ER stress elevates Grp78/Bip, the glucose-regulated protein and chaperone [37]. The chaperone interacts with the misfolded proteins and promotes refolding, thereby playing a critical role in regulating three ER transmembrane proteins, protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK), IRE-1α, and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) [38]. Diverse nanoparticles, including zinc oxide, silver nanoparticles, and iron oxide nanoparticles, were shown to elevate ER stress events [39, 40, 41]. However, only a few studies have shown that TiO2-NP could induce ER stress events in mammalian cells. Our data show that TiO2-NP could induce IRE-1α phosphorylation, elevate Grp78/Bip and CHOP, and activate the ER stress pathway in human bronchial epithelial cells. In addition, ER stress is strongly associated with the disruption of cellular Ca2+ homeostasis. The ER and mitochondria cooperatively regulate the cellular homeostatic network and act as physiological barriers against abnormal intracellular Ca2+ changes [42, 43]. Ca2+ translocates from the ER to the mitochondria through the MAMs. van Vliet et al. suggested that MAMs regulate energy metabolism, mitochondria biogenesis, and diverse signaling pathways involving ER stress and autophagy [15, 29]. To evaluate the effect of TiO2-NP on the MAMs, we evaluated specific proteins that have been identified in MAMs, including the IP3R, which plays a crucial role in Ca2+ handling in the ER, VDAC, and Grp75 [8, 44, 45]. Results of the fluorescence microscope imaging and western blot assay showed alterations in the MAM-related proteins following exposure to TiO2-NP (Fig 2A and 2B). ER stress decreases ER Ca2+ levels, which consequently reduces the expression of IP3R. IP3R functions as a transporter of Ca2+ from the ER to the mitochondria, and therefore, its decreased expression eventually diminishes the mitochondrial bioenergetics, leading to reduced cellular ATP production [46]. Furthermore, IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER is associated closely with increased levels of free cytoplasmic Ca2+, which activates autophagy [47]. Our data show that Ca2+ imbalance and abnormal autophagy increased following TiO2-NP exposure. In particular, decreased mitochondrial Ca2+ levels were detected with Rhod-2 AM staining in TiO2-NP-treated cells. The changes in the Ca2+ level affected the mitochondrial biogenesis disruption. In addition, we determined mitochondrial disorder by measuring the levels of proteins related to the respiration chain in the mitochondria and the ATP levels. To further support the correlation between ER stress and disruption of the MAMs, we treated cells with TUDCA, a bile acid that inhibits ER stress [29]. TUDCA pretreatment decreased ER stress and restored mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy (Fig 5).

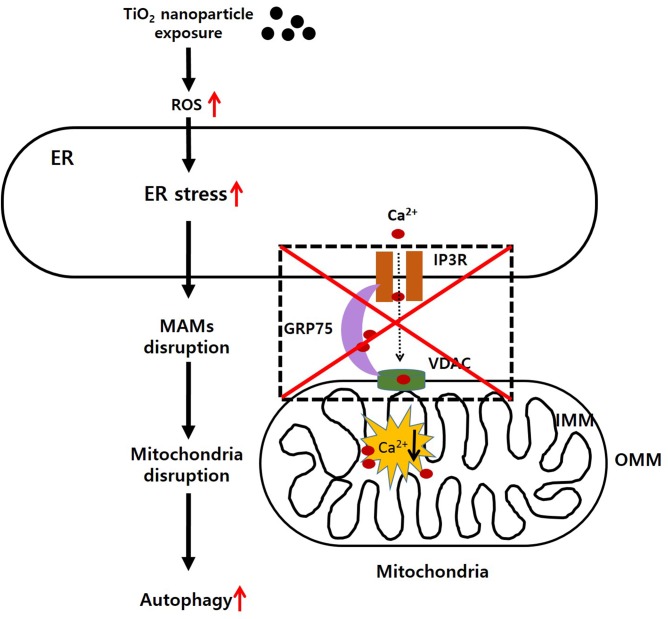

In conclusion, our data provide new evidence for the mechanism of TiO2-NP cytotoxicity, as demonstrated by increased ER stress effects, MAM disruption, dysfunction of mitochondria biogenesis, and autophagic cell death (Fig 6). The potential harmful effects of TiO2-NP nanoparticles have remained elusive. There are minimal regulatory guidelines from the government controlling their use for the industry. The safe widespread use of nanomaterials, including TiO2-NP, requires intensive study of their toxicities and mechanisms of action in relevant organisms. In future research, however, further works should be performed in order to discriminate whether observed results are due to the nanosized form or to the titanium component itself.

Fig 6. Schematic diagram of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NP) toxicity in human bronchial epithelial cells.

Based on our study, exposure of cells to TiO2-NP generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), which causes endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Induction of ER stress disrupts the mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) and causes mitochondrial calcium imbalance. Finally, autophagy is aberrantly induced and leads to cell death.

Supporting Information

XRD data of the rutile (red) and anatase (blue) forms of TiO2-NP and experimental materials (P-25, green).

(TIF)

After H2-DCFDA staining, we detected the fluorescence using confocal laser scanning microscopy. The green fluorescence intensity was calculated by Image J (Figure A). To assess the cell viability following TiO2-NP treatment, the MTT and WST-1 assays were performed. The optical densities of the samples were read on a microplate reader (Bio-Rad) at 450 nm. H2-DCFDA, 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (Figure B).

(TIF)

To monitor the state of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), calnexin, an ER state marker, was detected. Western blot analysis of calnexin (ER marker) after TiO2-NP treatment (Figure A). Immunofluorescence assay with calnexin after TiO2-NP treatment; scale bar, 10 μm (Figure B).

(TIF)

Immunofluorescence assay of IP3R (ER membrane, upper panel), Grp75 (middle panel), and VDAC1 (mitochondrial outer membrane, bottom panel; blue, DAPI-nucleus). IP3R, inositol triphosphate receptor; VDAC1, voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1; Grp75, 75 kDa glucose regulated protein.

(TIF)

To monitor the state of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) after TUDCA treatment, calnexin, an ER state marker, was detected. Immunofluorescence assay of calnexin after TUDCA (ER stress inhibitor) treatment and with TiO2-NP; green, calnexin; blue, DAPI-nucleus. TUDCA, tauroursodeoxycholic acid.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by funding provided to Myung-Haing Cho by the Research Institute for Veterinary Science, Seoul National University, and the BK21 PLUS Program for Creative Veterinary Science Research. We also thank Yong Jae Kim (National Center for Inter-University Research Facilities, Seoul National University) for technical assistance in the CLSM imaging.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was partially supported by funding provided to Myung-Haing Cho by the Research Institute for Veterinary Science, Seoul National University, and the BK21 PLUS Program for Creative Veterinary Science Research. KNY, SHC, SJP, J. Lim, J. Lee, TJY, JSK, MHC received funding from the Ministry of Science, ICT, & Future Planning (NRF-2015M3A7B6027957) (www.msip.go.kr). KNY, MHC received funding from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (14182MFDS977) (www.mfds.go.kr). Co-authors Soo Jin Park and Jun-Sung Kim are employed by R&D Center, Biterials, Co. Biterials Co. provided support in the form of salaries for authors SJP and J-SK, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section.

References

- 1. Afaq F, Abidi P, Matin R., Rahman Q. Cytotoxicity, pro-oxidant effects and antioxidant depletion in rat lung alveolar macrophages exposed to ultrafine titanium dioxide. J Appl Toxicol. 1998;18: 307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gwinn MR, Vallyathan V. Nanoparticles: Health effects–pros and cons. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114: 1818–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Long TC, Tajuba J, Sama P, Saleh N, Swartz C, Parker J, et al. Nanosize titanium dioxide stimulates reactive oxygen species in brain microglia and damages neurons in vitro. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115: 1631–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shi H, Magaye R, Castranova V, Zhao J. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles: a review of current toxicological data. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2013;10: 15 10.1186/1743-8977-10-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yin ZF, Wu L, Yang HG, Su YH. Recent progress in biomedical applications of titanium dioxide. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2013;15: 4844–4858. 10.1039/c3cp43938k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li J, Wang X, Jiang H, Lu X, Zhu Y, Chen B. New strategy of photodynamic treatment of TiO2 nanofibers combined with celastrol for HepG2 proliferation in vitro. Nanoscale. 2011;3: 3115–3122. 10.1039/c1nr10185d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Triesscheijn M, Baas P, Schellens JH, Stewart FA. Photodynamic therapy in oncology. Oncologist. 2006;11: 1034–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhattacharya K, Davoren M, Boertz J, Schins RP, Hoffmann E, Dopp E. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress and DNA-adduct formation but not DNA-breakage in human lung cells. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2009; 6: 17 10.1186/1743-8977-6-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tang Y, Wang F, Jin C, Liang H, Zhong X, Yang Y. Mitochondrial injury induced by nanosized titanium dioxide in A549 cells and rats. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2013; 36: 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oesch F, Landsiedel R. Genotoxicity investigations on nanomaterials. Arch. Toxicol. 2012; 86: 985–994. 10.1007/s00204-012-0838-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sager TM, Kommineni C, Castranova V. Pulmonary response to intratracheal instillation of ultrafine versus fine titanium dioxide: role of particle surface area. Part Fibre Toxicol 2008; 5:17 10.1186/1743-8977-5-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oberdorster G, Ferin J, Lehnert BE. Correlation between particle size, in vivo particle persistence, and lung injury. Environ Health Perspect. 1994; 102:173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferin J, Oberdörster G, Penney DP. Pulmonary retention of ultrafine and fine particles in rats. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1992; 6: 535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malhotra JD, Kaufman RJ. ER stress and its functional link to mitochondria: role in cell survival and death. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3: a004424 10.1101/cshperspect.a004424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Vliet AR, Verfaillie T, Agostinis P. New functions of mitochondria associated membranes in cellular signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843: 2253–2262. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernales S, McDonald KL, Walter P. Autophagy counterbalances endoplasmic reticulum expansion during the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 2006;4: e423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu KN, Yoon TJ, Minai-Tehrani A, Kim JE, Park SJ, Jeong MS, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticle induced autophagic cell death and mitochondrial damage via reactive oxygen species generation. Toxicol In Vitro. 2013;27: 1187–1195. 10.1016/j.tiv.2013.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jeong MS, Cho HS, Park SJ, Song KS, Ahn KS, Cho MH, et al. Physico-chemical characterization-based safety evaluation of nanocalcium. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;62: 308–317. 10.1016/j.fct.2013.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murdock RC, Braydich-Stolle L, Schrand AM, Schlager JJ, Hussain SM. Characterization of nanomaterial dispersion in solution prior to in vitro exposure using dynamic light scattering technique Toxicol Sci. 2008;101:239–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2005;1: 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meyer T, Wensel T, Stryer L. Kinetics of calcium channel opening by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Biochemistry. 1990;29: 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lihavainen E, Mäkelä J, Spelbrink JN, Ribeiro AS. Mytoe: automatic analysis of mitochondrial dynamics. Bioinformatics. 2012;28: 1050–1051. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shim SE, Lee H, Choe S. Synthesis of Functionalized Monodisperse Poly(methyl methacrylate) Nanoparticles by a RAFT Agent Carrying Carboxyl End Group. Macromolecules. 2004;37: 5565–5571. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Papa FR, Zhang C, Shokat K, Walter P. Bypassing a kinase activity with an ATP-competitive drug. Science. 2003;302: 1533–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schrag JD, Bergeron JJ, Li Y, Borisova S, Hahn M, Thomas DY, et al. The Structure of calnexin, an ER chaperone involved in quality control of protein folding. Mol Cell. 2001;8: 633–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Torres M, Encina G, Soto C, Hetz C. Abnormal calcium homeostasis and protein folding stress at the ER: A common factor in familial and infectious prion disorders. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4: 258–261. 10.4161/cib.4.3.15019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. González-Rodríguez A, Mayoral R, Agra N, Valdecantos MP, Pardo V, Miquilena-Colina ME, et al. Impaired autophagic flux is associated with increased endoplasmic reticulum stress during the development of NAFLD. Cell Death Dis. 2014;17: e1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kadowaki M, Karim MR. Cytosolic LC3 ratio as a quantitative index of macroautophagy. Methods Enzymol. 2009;452: 199–213. 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03613-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miller SD, Greene CM, McLean C, Lawless MW, Taggart CC., O’Neill SJ, et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid inhibits apoptosis induced by Z alpha-1 antitrypsin via inhibition of Bad. Hepatology. 2007;46: 496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Apopa PL, Qian Y, Shao R, Guo NL, Schwegler-Berry D, Pacurari M, et al. Iron oxide NPs induce human microvascular endothelial cell permeability through reactive oxygen species production and microtubule remodeling. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2009;6: 1–14. 10.1186/1743-8977-6-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Naqvi S, Samim M, Abdin M, Ahmed FJ, Maitra A, Prashant C, et al. Concentration-dependent toxicity of iron oxide nanoparticles mediated by increased oxidative stress. Int J Nanomedicine. 2010;5: 983–989. 10.2147/IJN.S13244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32. Buyukhatipoglu K, Clyne AM. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles change endothelial cell morphology and mechanics via reactive oxygen species formation. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;96: 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nel A, Xia T, Madler L, Li N. Toxic potential of materials at the nanolevel. Science. 2006;311: 622–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Du H, Zhu X, Fan C, Xu S, Wang Y, Zhou Y. Oxidative damage and OGG1 expression induced by a combined effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles and lead acetate in human hepatocytes. Environ Toxicol. 2012;27:590–597. 10.1002/tox.20682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saquib Q, Al-Khedhairy AA, Siddiqui MA, Abou-Tarboush FM, Azam A, Musarrat J. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles induced cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and DNA damage in human amnion epithelial (WISH) cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2012;26:351–361. 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Groenendyk J, Sreenivasaiah PK, Kim do H, Agellon L B, Michalak M. Biology of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart. Circ Res. 2010;107:1185–1197. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kozutsumi Y, Segal M, Normington K, Gething MJ, Sambrook J. The presence of malfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum signals the induction of glucose-regulated proteins. Nature. 1988;332:462–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Christopher CG. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart. Circ Res. 2007;101: 975–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yang X, Shao H, Liu W, Gu W, Shu X, Mo Y, Chen X, Zhang Q, Jiang M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress are involved in ZnO nanoparticle-induced hepatotoxicity. Toxicol Lett. 2015;234:40–49. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simard JC, Vallieres F, de Liz R, Lavastre V, Girard D. Silver nanoparticles induce degradation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor activating transcription factor-6 leading to activation of the NLRP-3 inflammasome. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:5926–5939. 10.1074/jbc.M114.610899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Park EJ, Choi DH, Kim Y, Lee EW, Song J, Cho MH, Kim JH, Kim SW. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles induce autophagy preceding apoptosis through mitochondrial damage and ER stress in RAW264.7 cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2014;28:1402–1412. 10.1016/j.tiv.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pozzan T, Rizzuto R. High tide of calcium in mitochondria. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2: 25–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bernardi P, Petronilli V, Di Lisa F, Forte M. A mitochondrial perspective on cell death. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26: 112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Carrington W, Fay FS, Fogarty KE, Lifshitz LM, et al. Close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+ responses. Science. 1998;280: 1763–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Szabadkai G, Bianchi K, Várnai P, De Stefani D, Wieckowski MR, Cavagna D, et al. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J Cell Biol. 2006;175: 901–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sano R, Hou YC, Hedvat M, Correa RG, Shu CW, Krajewska M, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum protein BI-1 regulates Ca²⁺-mediated bioenergetics to promote autophagy. Genes Dev. 2012;26: 1041–1054. 10.1101/gad.184325.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Decuypere JP, Welkenhuyzen K, Luyten T, Ponsaerts R, Dewaele M, Molgó J, et al. Ins(1,4,5)P3 receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling and autophagy induction are interrelated. Autophagy 2011;7: 1472–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

XRD data of the rutile (red) and anatase (blue) forms of TiO2-NP and experimental materials (P-25, green).

(TIF)

After H2-DCFDA staining, we detected the fluorescence using confocal laser scanning microscopy. The green fluorescence intensity was calculated by Image J (Figure A). To assess the cell viability following TiO2-NP treatment, the MTT and WST-1 assays were performed. The optical densities of the samples were read on a microplate reader (Bio-Rad) at 450 nm. H2-DCFDA, 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (Figure B).

(TIF)

To monitor the state of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), calnexin, an ER state marker, was detected. Western blot analysis of calnexin (ER marker) after TiO2-NP treatment (Figure A). Immunofluorescence assay with calnexin after TiO2-NP treatment; scale bar, 10 μm (Figure B).

(TIF)

Immunofluorescence assay of IP3R (ER membrane, upper panel), Grp75 (middle panel), and VDAC1 (mitochondrial outer membrane, bottom panel; blue, DAPI-nucleus). IP3R, inositol triphosphate receptor; VDAC1, voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1; Grp75, 75 kDa glucose regulated protein.

(TIF)

To monitor the state of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) after TUDCA treatment, calnexin, an ER state marker, was detected. Immunofluorescence assay of calnexin after TUDCA (ER stress inhibitor) treatment and with TiO2-NP; green, calnexin; blue, DAPI-nucleus. TUDCA, tauroursodeoxycholic acid.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.