Abstract

Background:

Intravenous (IV) acetaminophen is increasingly used around the world for pain control for a variety of indications. However, it is unclear whether IV administration offers advantages over oral administration.

Objective:

To identify, summarize, and critically evaluate the literature comparing analgesic efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics for IV and oral dosage forms of acetaminophen.

Data Sources:

A literature search of the PubMed, Embase, and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts databases was supplemented with keyword searches of Science Direct, Wiley Library Online, and Springer Link databases for the period 1948 to November 2014. The reference lists of identified studies were searched manually.

Study Selection and Data Extraction:

Randomized controlled trials comparing IV and oral dosage forms of acetaminophen were included if they assessed an efficacy, safety, or pharmacokinetic outcome. For each study, 2 investigators independently extracted data (study design, population, interventions, follow-up, efficacy outcomes, safety outcomes, pharmacokinetic outcomes, and any other pertinent information) and completed risk-of-bias assessments.

Data Synthesis:

Six randomized clinical trials were included. Three of the studies reported outcomes pertaining to efficacy, 4 to safety, and 4 to pharmacokinetics. No clinically significant differences in efficacy were found between the 2 dosage forms. Safety outcomes were not reported consistently enough to allow adequate assessment. No evidence was found to suggest that increased bioavailability of the IV formulation enhances efficacy outcomes. For studies reporting clinical outcomes, the results of risk-of-bias assessments were largely unclear.

Conclusions:

For patients who can take an oral dosage form, no clear indication exists for preferential prescribing of IV acetaminophen. Decision-making must take into account the known adverse effects of each dosage form and other considerations such as convenience and cost. Future studies should assess multiple-dose regimens over longer periods for patients with common pain indications such as cancer, trauma, and surgery.

Keywords: acetaminophen, paracetamol, intravenous, analgesia, pain

RÉSUMÉ

Contexte :

L’administration intraveineuse d’acétaminophène est de plus en plus employée partout dans le monde pour combattre la douleur due à toute une gamme de causes. Cependant, on ignore si elle offre des avantages comparativement à l’administration d’acétaminophène par voie orale.

Objectif :

Relever, résumer et faire une évaluation critique de la littérature qui compare l’efficacité analgésique, la sécurité et le comportement pharmacocinétique des formes pharmaceutiques intraveineuse et orale d’acétaminophène.

Sources des données :

Une recherche documentaire dans les bases de données de PubMed, Embase et International Pharmaceutical Abstracts a été complétée à l’aide de recherches de mots clés dans les bases de données de Science Direct, Wiley Library Online et Springer Link entre 1948 et novembre 2014. Un examen des bibliographies des études retenues a été réalisé manuellement.

Sélection des études et extraction des données :

Les essais cliniques à répartition aléatoire comparant les formes pharmaceutiques intraveineuse et orale d’acétaminophène ont été inclus lorsqu’ils évaluaient des résultats sur l’efficacité, la sécurité ou la pharmacocinétique. Pour chaque étude, deux chercheurs travaillant de façon indépendante ont extrait des données (sur le plan de l’étude, la population, les interventions, le suivi, l’efficacité, la sécurité, la pharmacocinétique et sur toute autre information pertinente) et ils ont rempli des évaluations du risque de biais.

Synthèse des données :

Au total, six essais cliniques à répartition aléatoire ont été retenus aux fins de l’analyse. Parmi ceux-ci, trois présentaient des résultats sur l’efficacité, quatre sur la sécurité et quatre sur la pharmacocinétique. Aucune différence cliniquement significative quant à l’efficacité n’a été relevée entre les deux formes pharmaceutiques. Les résultats sur la sécurité n’étaient pas présentés assez systématiquement pour permettre une évaluation pertinente. Aucune donnée n’a été trouvée permettant de croire que la biodisponibilité accrue de la préparation intraveineuse augmente l’efficacité. Pour les études présentant des résultats cliniques, le bilan des évaluations du risque de biais était en grande partie équivoque.

Conclusions :

Il n’y a pas d’indication claire favorisant la prescription d’acétaminophène par voie intraveineuse chez les patients en mesure de prendre la forme pharmaceutique orale. Tout choix doit tenir compte des effets indésirables propres à chaque forme pharmaceutique ainsi que d’autres facteurs, notamment la commodité et le coût. Des études ultérieures devraient évaluer les schémas à dose multiples sur une plus longue période chez les patients souffrant de douleurs courantes telles que celles causées par un cancer, un trauma ou une chirurgie.

Keywords: acétaminophène, paracétamol, administration intraveineuse, analgésie, douleur

INTRODUCTION

Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is recognized as one of the most commonly used synthetic, nonopioid, centrally acting analgesic agents. It represents a key part of pain management in patients with cancer, and is used preoperatively, intraoperatively, and postoperatively in a wide range of surgical settings, offering effective and fast pain relief.1–4 Acetaminophen has a well-established efficacy profile, favourable adverse drug reaction profile, and very low potential for harmful drug–drug interactions.5

Acetaminophen has been available in oral and rectal formulations for decades. However, controversy exists regarding the suitability of these formulations for use in some settings, such as postoperative or acute care.6,7 Intravenous (IV) acetaminophen was first commercialized in Europe, in 2002. Later, in 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration approved an IV formulation of acetaminophen for management of mild to moderate pain, management of moderate to severe pain with adjunctive opioid analgesics, and reduction of fever in adults and children 2 years and older.8 Since then, acetaminophen has become one of very few nonopioid analgesics available in oral, rectal, and IV formulations.9

The efficacy of IV administration of acetaminophen relative to placebo was recently established in a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials assessing patient satisfaction with acute postoperative pain control.10 The 5 trials that were included rated patient satisfaction on a 4-point scale 24 h after dosing. The analysis showed that patients who received IV acetaminophen reported excellent satisfaction with pain control more often than those who received placebo (32.3% versus 15.9%). IV acetaminophen was the strongest predictor of excellent patient satisfaction in a multivariate analysis (odds ratio [OR] 2.76, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.81 to 4.23). Therefore, compared with placebo, IV acetaminophen was deemed efficacious for patients presenting with acute pain.10

Other considerations have deemed the IV route for administration of acetaminophen advantageous in certain situations, such as when the oral or rectal route is unsuitable or ineffective (e.g., because of emesis) or when the high variability in bioavailability with rectal administration is unacceptable for a particular patient.8,9,11 IV administration has become the route of choice for rapid analgesia in inpatient and postoperative settings, largely because of evidence suggesting it may reduce the need for other analgesics such as opioids.2,10,12,13 One of the main clinical and practical advantages associated with IV administration is the faster onset of analgesia relative to an equivalent oral dose. In addition, IV administration is associated with more predictable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic behaviour.4,7,12,14 Another potential advantage of IV administration of acetaminophen is avoidance of first-pass hepatic exposure through the portal circulation, which may reduce the potential for hepatic injury.15–18

Despite the advantages offered by IV administration of acetaminophen, the choice of this route over oral administration should also take into account associated risks and inconveniences. Indeed, the risks associated with IV administration of most drugs include infection, phlebitis, and local irritation. Furthermore, the time needed for IV drug administration, the inconvenience to patients, and the increased direct and indirect costs suggest that the most suitable route of administration should be carefully selected for each patient. This is especially true in situations where the clinician may believe that IV therapy is better or faster-acting than oral formulations. In particular, the IV formulation of acetaminophen has a higher cost and longer administration time (15 min) than oral forms,19 factors that must be considered during therapeutic decision-making.

It is currently unclear whether IV administration of acetaminophen is more effective and equally safe compared to oral administration for patients with pain. The objective of this systematic review was to identify, summarize, and critically evaluate the literature comparing analgesic efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics for IV and oral dosage forms of acetaminophen.

METHODS

A literature search was completed using the databases PubMed (1948 to January 2015), EMBASE (1980 to January 2015), and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970 to January 2015), supplemented with keyword searches of Science Direct, Wiley Library Online, and Springer Link databases. Databases were searched using the keywords “acetaminophen” OR “paracetamol” combined with “intravenous” OR “infusion” OR “injection”, and “pain” OR “analgesia” OR “analgesic” using AND to combine search term categories. Keywords were searched as free text in International Pharmaceutical Abstracts but were linked to MeSH terms (Medical Subject Headings) in PubMed and EMBASE, where applicable. The website clinicaltrials.gov was searched for ongoing or potentially unpublished studies. Included studies were limited to those conducted in humans and published in English. The reference lists of identified studies were manually reviewed to supplement the electronic search methods.

Studies were selected on the basis of the following predefined inclusion criteria: randomized trials in adult humans that reported at least one clinical or pharmacokinetic outcome. Studies were included if they reported outcomes for an IV formulation of acetaminophen and a comparator group that received oral acetaminophen. Studies assessing the prodrug, propacetamol, were excluded because of its non-availability and association with adverse effects that might have biased safety outcomes. Nonrandomized studies and studies that did not include both IV and oral routes were excluded. Outcomes of interest were efficacy outcomes (e.g., pain scores, opioid-sparing, use of as-needed pain medications, length of stay), safety outcomes (e.g., incidence of adverse events or serious adverse events), and pharmacokinetic outcomes (e.g., maximum plasma concentration [Cmax], time to maximum plasma concentration [Tmax], area under the curve [AUC], and bioavailability). No exclusion criteria were set based on study quality markers.

Data for the main analysis (study design, population, interventions, follow-up, efficacy outcomes, safety outcomes, pharmacokinetic outcomes, and any other pertinent information) were extracted from each study by 2 of the investigators using a standardized extraction tool. Extraction results were cross-examined and assessed for discrepancies, which were resolved by discussion if needed. A third investigator was consulted for discrepancies that could not be resolved by discussion. Data pertaining to risk of bias were extracted according to the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk-of-bias assessment tool.20 Data extracted for assessment of risk of bias included information about random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other biases based on study design or identified confounders. Each component was ranked on a categorical scale for each domain (high risk of bias, low risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias). Two investigators extracted these data from each study and ranked each component. The results were cross-examined and discrepancies resolved according to the methods described above.

RESULTS

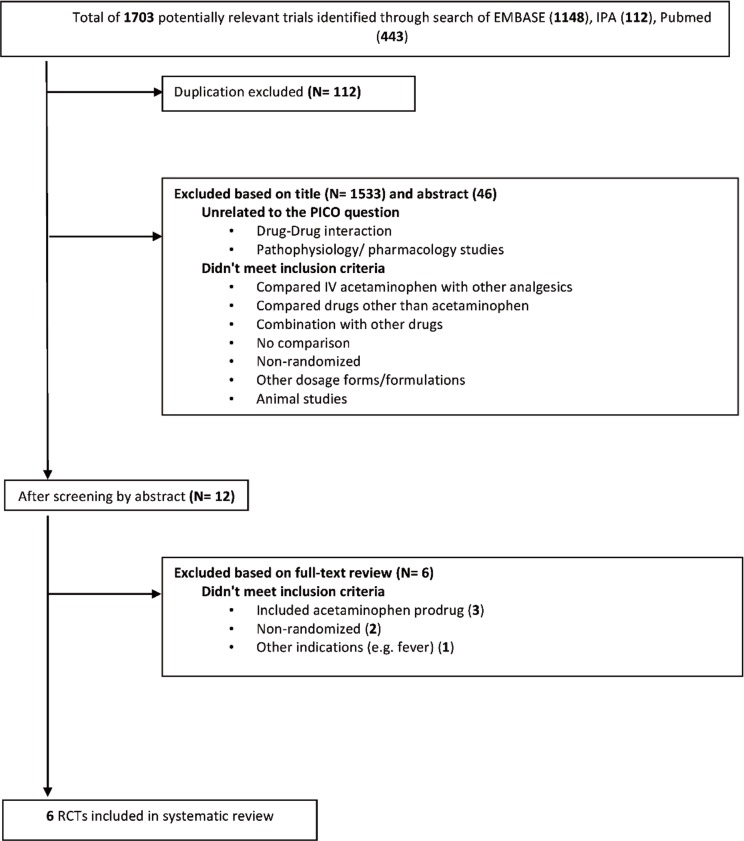

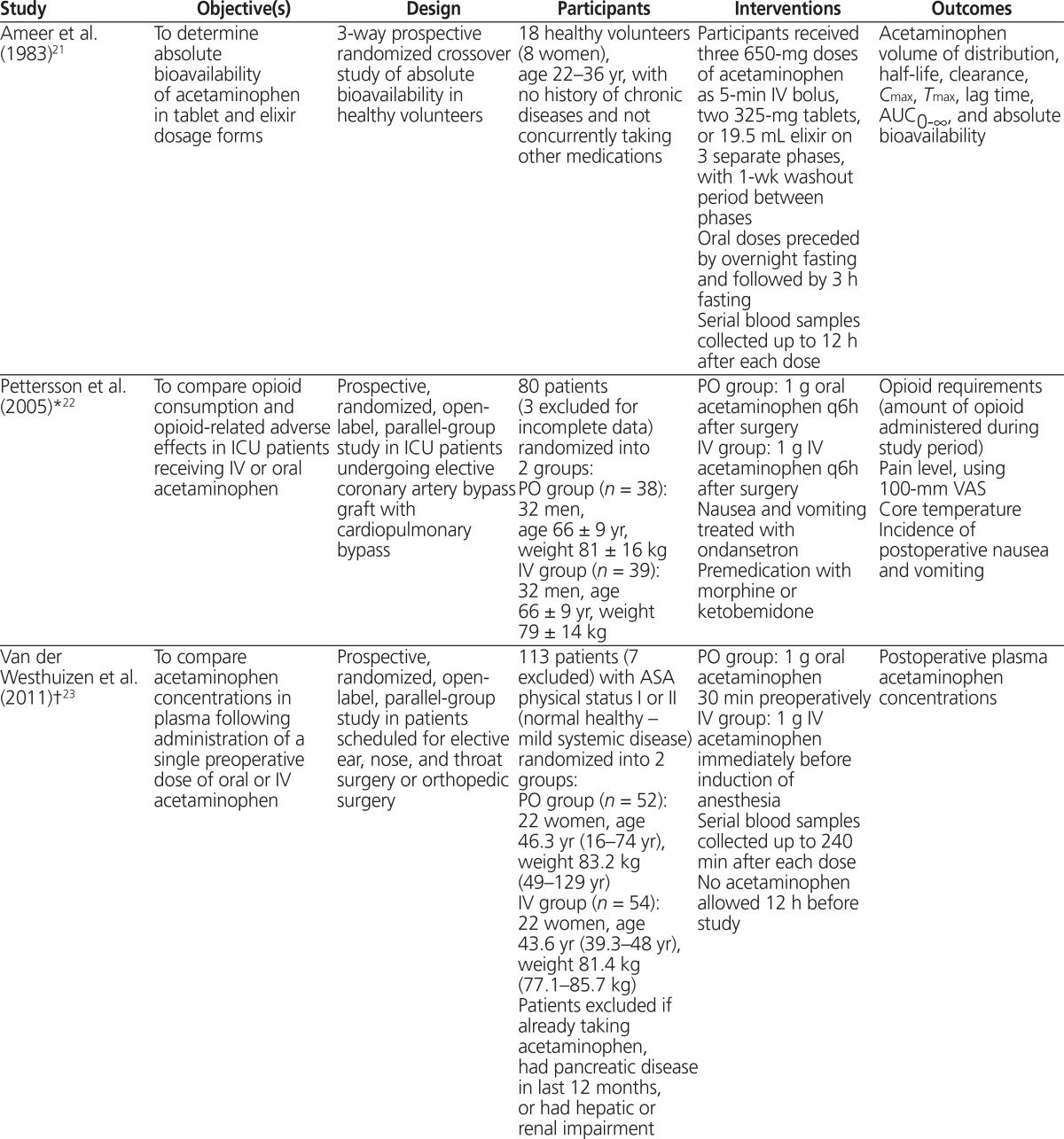

A total of 6 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review.21–26 The results of the search strategy, with reasons for exclusions, are given in Figure 1. The characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1, with outcome results for each study in Table 2 and risk-of-bias assessments in Table 3. All of the included studies were prospective randomized clinical trials, of which 4 were designed to use parallel groups22–24,26 and 2 were designed to use a 3-way randomized crossover method21,25 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Results of search strategy and study selection.

Table 1.

Summary of Study Characteristics (part 1 of 2)

| Study | Objective(s) | Design | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ameer et al. (1983)21 | To determine absolute bioavailability of acetaminophen in tablet and elixir dosage forms | 3-way prospective randomized crossover study of absolute bioavailability in healthy volunteers | 18 healthy volunteers (8 women), age 22–36 yr, with no history of chronic diseases and not concurrently taking other medications | Participants received three 650-mg doses of acetaminophen as 5-min IV bolus, two 325-mg tablets, or 19.5 mL elixir on 3 separate phases, with 1-wk washout period between phases Oral doses preceded by overnight fasting and followed by 3 h fasting Serial blood samples collected up to 12 h after each dose |

Acetaminophen volume of distribution, half-life, clearance, Cmax, Tmax, lag time, AUC0–∞, and absolute bioavailability |

| Pettersson et al. (2005)*22 | To compare opioid consumption and opioid-related adverse effects in ICU patients receiving IV or oral acetaminophen | Prospective, randomized, open-label, parallel-group study in ICU patients undergoing elective coronary artery bypass graft with cardiopulmonary bypass | 80 patients (3 excluded for incomplete data) randomized into 2 groups: PO group (n = 38): 32 men, age 66 ± 9 yr, weight 81 ± 16 kg IV group (n = 39): 32 men, age 66 ± 9 yr, weight 79 ± 14 kg | PO group: 1 g oral acetaminophen q6h after surgery IV group: 1 g IV acetaminophen q6h after surgery Nausea and vomiting treated with ondansetron Premedication with morphine or ketobemidone | Opioid requirements (amount of opioid administered during study period) Pain level, using 100-mm VAS Core temperature Incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting |

| Van der Westhuizen et al. (2011)†23 | To compare acetaminophen concentrations in plasma following administration of a single preoperative dose of oral or IV acetaminophen | Prospective, randomized, open-label, parallel-group study in patients scheduled for elective ear, nose, and throat surgery or orthopedic surgery | 113 patients (7 excluded) with ASA physical status I or II (normal healthy – mild systemic disease) randomized into 2 groups: PO group (n = 52): 22 women, age 46.3 yr (16–74 yr), weight 83.2 kg (49–129 yr) IV group (n = 54): 22 women, age 43.6 yr (39.3–48 yr), weight 81.4 kg (77.1–85.7 kg) Patients excluded if already taking acetaminophen, had pancreatic disease in last 12 months, or had hepatic or renal impairment | PO group: 1 g oral acetaminophen 30 min preoperatively IV group: 1 g IV acetaminophen immediately before induction of anesthesia Serial blood samples collected up to 240 min after each dose No acetaminophen allowed 12 h before study |

Postoperative plasma acetaminophen concentrations |

| Brett et al. (2012)‡4 | To compare acetaminophen concentrations in plasma in early postoperative phase following intraoperative IV and preoperative oral acetaminophen | Prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study in patients scheduled for day-case knee arthroscopy under genera anesthesia | 30 patients with ASA physical status I–II (normal healthy – mild systemic disease) randomized into 2 groups: PO group (n = 20): 8 women, age 50.3 ± 14.7 yr, BMI 27.9 ± 4.1 kg/m2 IV group (n = 10): 3 women, age 50.7 ± 13.3 yr, BMI 27.5 ± 4.4 kg/m2 | PO group: 1 g oral acetaminophen 30–60 min preoperatively IV group: 1 g acetaminophen IV infusion over 15 min Intraoperatively and oral placebo preoperatively to ensure blinding IV fentanyl used in both groups for intraoperative analgesia and as postoperative rescue analgesic if VAS score > 30 mm |

Plasma concentration of acetaminophen 30 min after surgery (primary) Postoperative VAS scores (100-mm scale assessed at 10-min intervals while patient awake in recovery room) Postoperative fentanyl requirements Length of stay in recovery area |

| Singla et al. (2012)25 | To compare plasma and CSF concentration–time curves and PK parameters for acetaminophen after IV, oral, and rectal administration | Prospective, randomized, open-label 3-way crossover study | 7 healthy nonsmoking men, age 19–44 yr, BMI 19–25.6 kg/m2, weight ≥ 50 kg No medications for 7 days before study; no history of excessive bleeding, recent infection, elevated intracranial pressure, neurological disease, or lumbar spine deformities |

Participants received 1-g dose of acetaminophen IV infusion over 15 min, 1-g dose of oral acetaminophen, and 1.3-g dose of acetaminophen rectal suppositories, with 24-h washout period between doses Serial plasma and CSF samples collected up to 6 h after each dose | Acetaminophen Cmax, Tmax, and AUC0–6 in plasma and CSF Plasma half-life of acetaminophen Regular safety assessments and self-reporting of adverse effects |

| Fenlon et al. (2013)26 | To compare postoperative analgesia after preoperative oral and IV acetaminophen | Prospective, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy parallel-group non-inferiority study in patients visiting a maxillofacial outpatient clinic | 128 patients, age 18–65 yr, who underwent at least one lower third molar extraction under general anesthesia randomized into 2 groups: PO group (n = 65): 51 women, age 18.1–57.7 yr, BMI 24.4 ± 4.3 kg/m2 IV group (n = 63): 43 women, age 18.7–54.4 yr, BMI 24.5 ± 5.0 kg/m2 No analgesics or caffeine for 24 h and 6 h before study, respectively | PO group: 1 g oral acetaminophen at least 45 min before surgery IV group: 1 g IV acetaminophen immediately after induction of anesthesia Both groups received appropriate placebo (oral tablets or IV 0.9% normal saline) |

100-mm VAS score at 1 h after surgery Time to request rescue analgesia VAS score at time of rescue analgesia Any adverse events reported |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists, AUC0–∞ = area under the plasma concentration curve, AUC0–6 = area under the plasma concentration–time curve from 0 to 6 h, BMI = body mass index, Cmax = maximum concentration, CSF = cerebrospinal fluid, ICU = intensive care unit, IV = intravenous, PK = pharmacokinetic, PO = oral, q6h = every 6 h, Tmax = time to maximum concentration, VAS = visual analogue scale.

Baseline characteristics presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Baseline characteristics presented as mean (range).

Baseline characteristics presented as mean ± standard error.

Table 2.

Summary of Clinical Efficacy, Safety, and Pharmacokinetic Results

| Study | Clinical Efficacy | Clinical Safety | Pharmacokinetic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ameer et al. (1983)*21 | Not evaluated | Not evaluated |

Tmax was significantly shorter with elixir than with tablet (0.48 ± 0.06 h vs. 0.76 ± 0.12 h; p < 0.025) Absolute bioavailability was significantly higher with elixir than with tablet (87% ± 2% vs. 79% ± 2%; p < 0.001) No statistically significant differences between elixir and tablet preparations in any other PK parameter |

| Pettersson et al. (2005)†22 | Amount of opioid used postoperatively was significantly lower with IV than with oral acetaminophen (1.5 ± 0.5 mg/kg vs. 1.9 ± 0.6 mg/kg; p = 0.008) No statistically significant differences in incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting, increase in body temperature, or mean VAS scores during ICU stay | Not evaluated | Not evaluated |

| Van der Westhuizen et al. (2011)23 | Not evaluated | No treatment-related side effects observed in either group | Therapeutic acetaminophen concentrations in plasma (> 10 mg/L) were achieved at any time in 96% of patients in IV group vs. 67% of patients in PO group (p < 0.0001) Median Cmax was significantly higher for IV group than for PO group (19 mg/L [IQR 15–23] vs. 13 mg/L [IQR <10–18]; p < 0.0001) Therapeutic acetaminophen concentrations maintained for 3 h with IV vs. 1.5 h with PO |

| Brett et al. (2012)*24 | Mean pain score at 50 min after surgery was significantly higher with PO than with IV administration (30.8 ± 5.8 mm vs. 11.6 ± 2.8 mm; p = 0.025) No statistically significant differences in fentanyl requirements, mean pain score at 30 min, or total time in recovery area |

No treatment-related side effects observed in either group | Mean acetaminophen concentrations 30 min after surgery were significantly higher with IV than with oral administration (88.6 ± 16.3 µmol/L vs. 53.2 ± 19.1 µmol/L; p = 0.0005) All patients in IV group had plasma concentrations above proposed analgesic level (66 µmol/L) vs. only 35% of patients in PO group |

| Singla et al. (2012)†25 | Not evaluated | Three participants experienced a total of 12 adverse reactions (e.g., postdural puncture headache, nausea, viral infection); none were deemed to be treatment-related | Mean plasma Cmax was significantly higher with IV than with PO administration (21.6 ± 3.9 µg/mL vs. 12.3 ± 5.6 µg/mL; p = 0.0004) and Tmax was significantly shorter (0.25 h vs. 1 h; p = 0.0018) Mean AUC0–6 45% higher with IV than with PO administration (p value not reported) No statistically significant difference in plasma half-life between the 2 groups Mean CSFmax was significantly higher with IV than with PO administration (5.94 ± 1.09 µg/mL vs. 3.72 ± 1.45 µg/mL; p < 0.0001) with no statistically significant differences in Tmax Mean CSF AUC0–6 was significantly higher with IV than with PO administration (24.9 ± 4.3 µg · h/mL vs. 14.2 ± 7.4 µg · h/mL; p = 0.009) |

| Fenlon et al. (2013)26 | Proportion of patients with VAS ≤ 30 mm at 1 h postoperatively showed non-inferiority of PO to IV acetaminophen (23.1% [95%CI 14%–35%] vs. 27.0% [95% CI 17%–40%]) No statistically significant differences in mean VAS scores, requirements for rescue analgesia, or time to rescue analgesia |

Dizziness after surgery (n = 1) and burn to the lip from surgical drill (n = 1); both deemed unrelated to acetaminophen treatment | Not evaluated |

AUC0–6 = area under the plasma concentration time curve from 0 to 6 h, CI = confidence interval, Cmax = maximum concentration, CSF = cerebral spinal fluid, CSFmax = maximum concentration in cerebrospinal fluid, ICU = intensive care unit, IQR = interquartile range, IV = intravenous, PK = pharmacokinetic, PO = oral, Tmax = time to maximum concentration, VAS = visual analogue scale.

Results presented as mean ± standard error.

Results presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Table 3.

Assessment of Risk of Bias

| Domain; Risk of Bias* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment | Blinding | Incomplete Data Outcome | Selective Outcome Reporting | Other |

| Ameer et al. (1983)†21 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Pettersson et al. (2005)22 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Van der Westhuizen et al. (2001)†23 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Brett et al. (2012)24 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Singla et al. (2012)25 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Fenlon et al. (2013)26 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

Risk of bias was categorized as low, high, or unclear.

Open-label study with low risk of bias because of objective pharmacokinetic outcomes.

Studies Reporting Efficacy Outcomes

Three of the studies identified reported efficacy outcomes.22,24,26 Pettersson and others22 compared the opioid-sparing effects of oral and IV acetaminophen in the postoperative setting, for patients who had undergone coronary artery bypass grafting. The study drug (acetaminophen, either oral or IV) was given when patients first awakened after surgery, and additional doses were given every 6 h until 0900 the next morning. The opioid used for rescue analgesia was an IV infusion of ketobemidone, with 8 mg of the IV formulation equalling about 10 mg of IV morphine. The use of opioids was significantly lower in the group receiving acetaminophen by the IV route than in the group receiving acetaminophen by the oral route (mean ± standard deviation 17.4 ± 7.9 mg versus 22.1 ± 8.6 mg; p < 0.05). However, this difference did not translate into a significant difference in rates of postoperative nausea and vomiting or any significant difference in pain scores on a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) at any time. Brett and others24 compared postoperative pain scores, length of stay in recovery, and opioid-sparing effects of oral and IV acetaminophen in patients who had undergone knee arthroscopy. No significant differences were found in terms of fentanyl requirements or length of stay in recovery. The only significant difference was in VAS scores (on a 100-mm scale), in favour of IV over oral administration (mean ± standard error 11.6 ± 2.8 mm versus 30.8 ± 5.8 mm; p = 0.025) at 50 min after arrival in recovery. However, it was noted that one-third of the patients had been discharged by this time point. Fenlon and others26 assessed VAS scores (on a 100-mm scale) as well as requests for and timing of rescue analgesia in patients undergoing extraction of the third molar. A non-inferiority margin was set at 20% difference in satisfactory pain control, defined as VAS scores ≤ 30 mm at 1 h postoperatively on a 100-mm VAS. This threshold was achieved in 23.1% of patients in the oral administration group and 27.0% of those in the IV administration group, giving a difference in proportions of −0.039 (90% CI −0.17 to 0.09). Because this result was within the 20% non-inferiority margin, oral acetaminophen was deemed non-inferior to IV acetaminophen. However, concerns about the study design and the statistical analysis were noted and are discussed below. No statistically significant differences were found in terms of requests for and timing of rescue analgesia.

Studies Reporting Safety Outcomes

Four of the studies reported on adverse events,23–26 but only 2 of these studies reported the occurrence of any adverse event.25,26 None of the adverse events was deemed to be associated with acetaminophen use.

Studies Reporting Pharmacokinetic Outcomes

Four of the studies reported pharmacokinetic outcomes.21,23–25 Ameer and others21 found that single doses of acetaminophen tablets or elixir achieved high bioavailability relative to IV formulations. The elixir formulation had significantly higher bioavailability than the tablets (87% versus 79%; p < 0.001) and shorter Tmax (0.48 h versus 0.76 h; p < 0.025). Singla and others25 reported 75% and 45% higher plasma Cmax and AUC0–6, respectively, following IV dosing relative to oral dosing. Furthermore, peak concentrations and AUC0–6 in cerebrospinal fluid were 60% higher and 75% higher, respectively, after IV dosing relative to oral dosing. Van der Westhuizen and others23 found that 96% of patients receiving the IV formulation achieved a target plasma acetaminophen concentration above 10 mg/L, as compared with only 67% in the oral group. Those results were confirmed by a significantly higher median Cmax after IV dosing relative to oral dosing (19 mg/L versus 13 mg/L; p < 0.0001). Similar results were reported by Brett and others,24 with 100% of patients in the IV group achieving plasma concentrations above 10 mg/L, compared with only 35% in the oral group. There was also a significant difference in mean plasma acetaminophen concentrations at 30 min after arrival in the recovery room in favour of the IV group (88.6 µmol/L versus 53.2 µmol/L; p = 0.0005).

Assessment of Risk of Bias

The risk-of-bias assessments are summarized in Table 3. Notably, studies that assessed only pharmacokinetic outcomes were generally deemed to have low risks of performance and detection biases (blinding domain), even if they were not blinded. In most cases, sequence generation was not reported in enough detail to assess randomization methods. Only one study reported allocation concealment methods.26 The study by Pettersson and others22 was the only one to receive a “high risk of bias” rating for the blinding domain, because of the open-label design and inclusion of outcomes that were subjective in nature. That study was also deemed to have an “unclear risk of bias” for the incomplete outcome data domain, because of the unjustified exclusion of data for 3 patients from the final data analysis. Studies were assigned a judgment of “unclear risk” of reporting bias if the study protocol was not available, and outcomes of interest were not prespecified in the methods section, for comparison with reported outcomes.23,25 Other examples of unclear bias included lack of sample size calculation21,25 and imbalance in patients’ baseline characteristics.26 Fenlon and others26 used a 90% CI to assess non-inferiority between dosage forms. This practice narrows the CI and may bias the results in favour of achieving non-inferiority. Other biases relating to study design were identified and deemed unclear (see Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This review has summarized and evaluated the available published literature describing efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetic outcomes of randomized studies assessing oral versus IV dosage forms of acetaminophen. Within studies conducted in populations requiring analgesia, the indications for pain control were diverse and inconsistent between studies. Of the 6 identified studies, 3 reported on efficacy, 4 on safety, and 4 on pharmacokinetic outcomes. The findings of each study were largely hypothesis-generating and can provide insight for the design of future randomized controlled trials attempting to assess these outcomes.

A major finding of this review was the absence of strong evidence suggesting superiority of IV acetaminophen administration over oral routes. Significant end points in the Pettersson and Brett trials for efficacy are called into question on the basis of clinical relevance and study design.22,24 For example, the significantly lower use of rescue opioids (ketobemidone) in the IV group in the study by Pettersson and others22 (17.4 mg versus 22.1 mg) is not clinically significant and would not justify preferentially giving postoperative IV therapy to patients who have undergone coronary artery bypass grafting. Similarly, the significant finding in the trial by Brett and others24 of a lower VAS score in the IV group at 50 min after entrance to recovery must be questioned, since one-third of patients had been discharged by that point. Therefore, on the basis of current evidence, if a patient has a functioning gastrointestinal tract and is able to take oral formulations, IV formulations are not indicated.

A systematic review published by the Cochrane Collaboration provides insight into the effect of IV acetaminophen in comparison with opioids and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.27 Although no differences were found between groups of identified studies in terms of pain reduction, the results must be interpreted cautiously, as small sample sizes precluded testing for superiority. It was noted, however, that IV acetaminophen may be useful for opioid-sparing in postoperative pain.27 To date, no strong evidence exists that IV acetaminophen should replace any form of standard care. At most, the evidence indicates that this formulation could function as an adjunctive agent in patients unable to take oral forms.

Among the studies reporting safety outcomes, none reported this information in enough detail to allow critical evaluation and formulation of conclusions. Although no treatment-related adverse effects were noted in any study, IV routes of administration are inherently associated with higher rates of adverse effects, as mentioned earlier. Additionally, all studies were based on single doses or short-term therapy, and the risks of long-term IV dosing could not be documented.

Four of the 6 studies evaluated pharmacokinetic outcomes, with only one study combining both pharmacokinetic and clinical efficacy outcomes.24 Ameer and others21 found that oral dosage forms of acetaminophen were associated with high bioavailability, with only 13% to 21% of the dose being lost during absorption. Similar results were obtained previously by Rawlins and others,28 who showed that bioavailability of acetaminophen tablet dosage forms increased from 63% after 500-mg doses to 89% after 1000-mg doses. Such bioavailability at doses used in the clinical setting may indicate dose equivalency between IV and oral dosage forms, which enhances interchangeability in the absence of efficacy differences.

Most studies including pharmacokinetic outcomes reported higher Cmax, shorter Tmax, higher postoperative plasma concentrations, and larger proportions of patients achieving target plasma concentrations after IV dosing compared with oral dosing. Such results may indicate superior efficacy for IV dosing; however, this can be confirmed only through a well-established concentration–response relationship, which is currently not available for acetaminophen. Target concentrations used in studies by Brett and others24 and van der Westhuizen and others23 are only proposed targets and have not been consistently shown to relate to analgesic outcomes in previous literature. Furthermore, Brett and others24 combined pharmacokinetic with clinical efficacy outcomes in an attempt to establish such a relationship. However, although their results showed higher plasma concentrations of acetaminophen after IV dosing than after oral dosing, this difference did not translate into differences in clinical efficacy. On the contrary, fentanyl requirements and mean VAS scores at the time of measurement of plasma concentrations were similar between the 2 groups. Such results indicate that differences in plasma exposure between IV and oral dosing may not necessarily result in differences in clinical outcomes.

At the time of writing (late 2014), IV acetaminophen was not widely available in Canada, yet was in common use in the United States, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. In the United States, there has been great debate regarding use of this formulation, which has led many hospitals to adopt policies and procedures that restrict use for a limited period or for patients not able to take medications by mouth. These restrictions are required because of the cost of the product, in addition to other administration-related inconveniences.19 Canadian hospitals and formulary committees should be aware of the available efficacy and safety data if the formulation is marketed in Canada and its use becomes widespread. Given the high cost and the lack of superiority over oral forms, Canadian hospitals may need to restrict use of the IV formulation, as their US counterparts have already done. However, these decisions will depend on marketing of the product in Canada. In addition to institution-based decision-making, pharmacists and other health care professionals should have baseline knowledge about this comparison in the event of drug information requests or for the education of patients or physicians coming from other regions where access has already been approved.

Recommendations can be made regarding future research in this area. According to anecdotal information, specific patient populations of interest are those with advanced cancer pain or trauma-related injuries, as well as those undergoing or recovering from surgical procedures. It is within these populations that IV therapy is commonly advocated, even when oral therapy can be tolerated. Studies should include both efficacy and safety outcomes and should assess multiple dosing (rather than single dosing) to better characterize longer-term use and differences relating to the dosage forms used in practice. Such studies could also include pharmacokinetic outcomes to allow a better understanding of pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic relationships and how parameters such as bioavailability, onset of action, and first-pass metabolism influence both efficacy and safety.

This study had some limitations. First, the studies identified were diverse in population, dosage regimens, and reported outcomes. This diversity inhibited the pooling of data by quantitative methods. Also, the identified studies were limited in number, which precluded generalizing results to all patients for whom acetaminophen therapy is indicated. Lastly, study quality markers were not consistently reported, which made the risk-of-bias assessment unclear for a large number of categories.

Despite these limitations, the data presented in this review allow for certain conclusions to be drawn. It is evident from the studies identified that there is no clear indication for IV acetaminophen over oral acetaminophen if patients have a functioning gastrointestinal tract and are able to take oral dosage forms. Although safety data were largely not assessed, decision-making must consider the known risks associated with IV administration before this form of administration is commonly recommended for patients who are able to take oral therapy. This situation represents an opportunity for pharmacists to be patient advocates by ensuring that clinicians are not inappropriately advocating IV therapy in practice. If the IV formulation is eventually approved in Canada, restriction policies and procedures may need to be established to prevent increases in health care costs and labour requirements without any major benefits in terms of efficacy and safety. Finally, future studies should focus on assessing multiple-dose regimens over longer periods for patients with common pain indications such as cancer, trauma, and surgery.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding: None received.

References

- 1.Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Rosenberg L, Anderson TE, Mitchell AA. Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States: the Slone survey. JAMA. 2002;287(3):337–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duggan ST, Scott LJ. Intravenous paracetamol (acetaminophen) Drugs. 2009;69(1):101–13. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prescott LF. Paracetamol (acetaminophen): a critical bibliographic review. London (UK): Taylor and Francis; 1996. The therapeutic use of paracetamol; pp. 253–99. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breivik H. Postoperative pain: towards optimal pharmacological and epidural analgesia. In: Giamberardino MA, editor. Pain 2002—an updated review: refresher course syllabus. Seattle (WA): IASP Press; 2002. pp. 337–49. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prescott LF. Paracetamol: past, present, and future. Am J Ther. 2000;7(2):143–7. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200007020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Candiotti KA, Bergese SD, Viscusi ER, Singla SK, Royal MA, Singla NK. Safety of multiple-dose intravenous acetaminophen in adult inpatients. Pain Med. 2010;11(12):1841–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Aken H, Thys L, Veekman L, Buerkle H. Assessing analgesia in single and repeated administrations of propacetamol for postoperative pain: comparison with morphine after dental surgery. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(1):159–65. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000093312.72011.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waknine Y. Medscape Medical News. New York (NY): WebMD LLC; 2010. FDA approves first intravenous formulation of acetaminophen. [cited 2014 Nov 21]. Available from: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/731994. Subscription required to access content. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malaise O, Bruyere O, Reginster JY. Intravenous paracetamol: a review of efficacy and safety in therapeutic use. Future Neurol. 2007;2(6):673–88. doi: 10.2217/14796708.2.6.673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Apfel CC, Souza K, Portillo J, Dalal P, Bergese SD. Patient satisfaction with intravenous acetaminophen: a pooled analysis of five randomized, placebo-controlled studies in the acute postoperative setting. J Healthc Qual. 2014 Jan 16; doi: 10.1111/jhq.12062. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arana A, Morton NS, Hansen TG. Treatment with paracetamol in infants. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45(1):20–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.450104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moller PL, Sindet-Pedersen S, Petersen CT, Juhl GI, Dillenschneider A, Skoglund LA. Onset of acetaminophen analgesia: comparison of oral and intravenous routes after third molar surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(5):642–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White PF. The role of non-opioid analgesic techniques in the management of pain after ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;94(3):577–85. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200203000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinatra RS, Jahr JS, Reynolds LW, Visusi ER, Groudine SB, Payen-Champenois C. Efficacy and safety of single and repeated administration of 1 gram intravenous acetaminophen injection (paracetamol) for pain management after major orthopedic surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;102(4):822–31. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200504000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirate J, Zhu CY, Horikoshi I, Bhargava VO. First-pass metabolism of acetaminophen in rats after low and high doses. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1990;11(3):245–52. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510110309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin JH, Chiba M, Baillie TA. Is the role of the small intestine in first-pass metabolism overemphasized? Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51(2):135–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumpulainen E, Kokki H, Halonen T, Heikkinen M, Savolainen J, Laisalmi M. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) penetrates readily into the cerebrospinal fluid of children after intravenous administration. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):766–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregoire N, Hovsepian L, Gualano V, Evene E, Dufour G, Gendron A. Safety and pharmacokinetics of paracetamol following intravenous administration of 5 g during the first 24 h with a 2-g starting dose. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81(3):401–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeh YC, Reddy P. Clinical and economic evidence for intravenous acetaminophen. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(6):559–79. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.2011.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ameer B, Divoll M, Abernethy DR, Greenblatt DJ, Shargel L. Absolute and relative bioavailability of oral acetaminophen preparations. J Pharm Sci. 1983;72(8):955–8. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600720832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pettersson PH, Jakobsson J, Owall A. Intravenous acetaminophen reduced the use of opioids compared with oral administration after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;19(3):306–9. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Westhuizen J, Kuo PY, Reed PW, Holder K. Randomised controlled trial comparing oral and intravenous paracetamol (acetaminophen) plasma levels when given as preoperative analgesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39(2):242–6. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1103900214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brett CN, Barnett SG, Pearson J. Postoperative plasma paracetamol levels following oral or intravenous paracetamol administration: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2012;40(1):166–71. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1204000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singla NK, Parulan C, Samson R, Hutchinson J, Bushnell R, Beja EG, et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetic parameters after single-dose administration of intravenous, oral, or rectal acetaminophen. Pain Pract. 2012;12(7):523–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fenlon S, Collyer J, Giles J, Bidd H, Lees M, Nicholson J, et al. Oral vs intravenous paracetamol for lower third molar extractions under general anaesthesia: is oral administration inferior? Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(3):432–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNicol ED, Tzortzopoulou A, Cepeda MS, Francia MB, Farhat T, Schumann R. Single-dose intravenous paracetamol or propacetamol for prevention or treatment of postoperative pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106(6):764–75. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rawlins MD, Henderson DB, Hijab AR. Pharmacokinetics of paracetamol (acetaminophen) after intravenous and oral administration. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1977;11(4):283–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00607678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]