Abstract

Small and large PEGs greatly increase chemical potentials of globular proteins (μ2), thereby favoring precipitation, crystallization, and protein-protein interactions that reduce water-accessible protein surface and/or protein-PEG excluded volume. To determine individual contributions of PEG-protein chemical and excluded volume interactions to μ2 as functions of PEG molality m3, we analyze published chemical potential increments μ23 = dμ2/dm3 quantifying unfavorable interactions of PEG (PEG200-PEG6000) with BSA and lysozyme. For both proteins, μ23 increases approximately linearly with the number of PEG residues (N3). A 1 molal increase in concentration of PEG -CH2OCH2- groups, for any chain-length PEG, increases μBSA by ~2.7 kcal/mol and μlysozyme by ~1.0 kcal/mol. These values are similar to predicted chemical interactions of PEG -CH2OCH2- groups with these protein components (BSA ~3.3 kcal/mol, lysozyme ~0.7 kcal/mol), dominated by unfavorable interactions with amide and carboxylate oxygens and counterions. While these chemical effects should be dominant for small PEGs, larger PEGS are expected to exhibit unfavorable excluded volume interactions and reduced chemical interactions because of shielding of PEG residues in PEG flexible coils. We deduce that these excluded volume and chemical shielding contributions largely compensate, explaining why the dependence of μ23 on N3 is similar for both small and large PEGs.

Introduction

Throughout his career Don Crothers was deeply interested the thermodynamics of interactions of biopolymers with water, solutes, salts and ligands, and the thermodynamic consequences of these interactions for biopolymer processes1,2. In this article in memory of Don, we develop a thermodynamic analysis of the interactions of polyethylene glycols (PEG) with proteins relevant for analyses of PEG effects on protein processes. Polyethylene glycols (PEGs) are remarkable solutes, with many significant applications in biochemistry, structural biology and the biomedical sciences including precipitating and crystallizing proteins3-9, solubilizing aromatic hydrocarbons10, and as osmotic and/or excluded volume agents11-17. Since both low and high molecular weight PEG can be effective protein precipitants, it is clear that chemical (preferential) as well as excluded volume interactions of PEGs with native proteins are typically unfavorable. Here we assess the individual contributions of chemical interactions and excluded volume effects to the increase in protein chemical potential (μprotein) upon addition of either low or high molecular weight PEG that makes these oligomers and polymers very effective perturbants of protein processes including protein crystallization.

We analyze an extensive set of dialysis-densimetry data6 quantifying derivatives dμprotein/dmPEG = μ23 quantifying effects of PEG concentration (PEG200 – PEG6000; component 3) on the chemical potentials of two proteins (component 2), bovine serum albumin (BSA) and lysozyme, which differ greatly in surface area and surface composition. Values of μ23 express the change in protein chemical potential (in kcal/mol) as the PEG concentration is increased by 1 molal; they are also equal to transfer free energies for the process of transferring the protein from a PEG-free solution to 1 molal PEG. Chemical interactions of any PEGs with these proteins are predicted using results of a recently-reported analysis of μ23 values for interactions of tetraEG and glycerol with model compounds18.

Our approach to separate chemical interactions and excluded volume effects of high molecular weight PEGs is similar to that used recently to separate these effects on melting of DNA hairpin helices and duplexes. Knowles et al 19 determined m-values (free energy derivatives dΔGoobs/dm3 = m-value = Δμ23) at 313 K quantifying effects of molal concentration m3 of ethylene glycol (EG) monomer and a series of PEGs from diEG to PEG20000 (number of monomer units N3 = 450) on standard free energy changes (ΔGoobs = -RTlnKobs) for melting a 12 bp duplex and a 12 base (4 bp) hairpin DNA oligomer. Values of Δμ23 obtained in this way are interpreted as the sum of two contributions: 1) helix-destabilizing, favorable preferential chemical interactions (PI) of the PEG with the primarily-nucleobase surface of DNA exposed in melting (Δμ23pi) and 2) the difference in DNA-PEG excluded volume (EV) interactions (Δμ23ev) between melted strand(s) and the helical form, favoring the latter. The analogous expression for μ23 is Eq. 1 (in Table 1 below).

Table 1.

Predictions of Chemical and Excluded Volume Contributions to PEG-Protein Interactions as a Function of PEG Size

| Observable: Chemical potential derivative μ23 quantifying PEG-protein interactiona | Eq.1 | |

| Chemical contribution from PEG-protein and PEG-ion interactionsb | Eq.2 | |

| Excluded volume contribution (large N3 limit)c | Eq.3 | |

| PEG-biopolymer excluded volumed (spherical proteins, DNA cylinders) | Eq.4 | |

| Combined chemical, χ and excluded volume contributions to μ23 in large N3 limit | Eq.5 |

In Eq.1, and are the chemical (preferential interaction) and excluded volume contributions to μ23, and χ is the average fraction of residues of a PEG chain molecule that are accessible to the protein.

In Eq.2, α, β are interaction potentials for the interaction of the indicated PEG group (two –CH2OH ends (α2E); interior –CH2OCH2- (αI)) with unit area of protein functional group i (see Figure 3 and ref.[18]) and with salt ions of the protein component (β2E, βI)

In Eq. 3, is the protein-PEG excluded volume (see Supplemental Materials).

In Eq. 4 [20], LK is PEG Kuhn length and NK is the number of Kuhn lengths per PEG molecule (see Supplemental Materials); NK LK = N3 l where l the length of a PEG residue (3.55 A for –CH2OCH2-). Expressions for the geometrical quantity k are given for spheres and cylinders [20]: r2 is sphere or cylinder radius, p=L2/r2 is the ratio of the length L2 to the radius of the cylinder (the aspect ratio) and for the cylinder, function C(p) is given in Supplemental Materials. Numerical factors in k are obtained from simulations [20].

Chemical interactions are deduced to be the primary contributor to DNA helix melting m-values for the smallest PEGs (≤ PEG200). For large PEGs both excluded volume effects and chemical interactions are found to be important, though for large PEG flexible coils chemical interactions are reduced on a per-residue basis because of shielding of PEG residues in the interior of a flexible coil from interaction with DNA. Both chemical (Δμ23pi) and excluded volume (Δμ23ev) contributions to the PEG m-value (Δμ23) are predicted to be proportional to PEG size (N3), and indeed proportionality of the PEG m-value to N3 is observed at both low and high N3, with very different proportionality constants in these two regimes of N3 (19; also see Fig 4 below).

Fig 4.

Analysis of m-Values Quantifying Effects of the Monomer-Polymer Series of PEGs (EG to PEG20000) on Stability of DNA Helices19. Panel A: Plot of monomolal PEG m-values (i.e. m-value/N3 = Δμ23/N3) vs. logN3. Panel B: Plot of molal scale PEG m-values (Δμ23) vs. number of interior PEG repeats (N3 – 1) for small and intermediate PEGs (N3 ≤ 14). Lines for N3 ≤ 3 are linear fits of EG, diEG and triEG m-values. Lines for N3 > 13 are from Panel C. Panel C: Plot of molal scale PEG m-values (Δμ23) vs. number of interior PEG repeats (N3 – 1) for all (N3 – 1) investigated. Lines are best fits to four (duplex) and five (hairpin) highest-N3 PEG m-values with floated intercepts.

Here we apply a similar analysis to the extensive data set collected by Bhat and Timasheff 6 quantifying effects of the PEG series PEG200-PEG6000 on chemical potentials of native lysozyme and BSA by dialysis and densimetry. These data, summarized in Fig. 1, reveal that observed μ23 values are approximately proportional to N3 over the full range of PEG sizes investigated (PEG 200–PEG 6000; 4 ≤ N3 ≤ 136). We predict chemical interaction contributions to the PEG-protein μ23 from PEG interior and end groups, and predict the excluded volume contribution to μ23 for large PEGs. Predictions based on net-unfavorable chemical interactions alone, with no shielding correction, are unexpectedly in semi-quantitative agreement with PEG- protein μ23 values, exhibiting near-proportionality of μ23 to N3 for the full range of PEG sizes investigated. But unfavorable excluded volume effects (also proportional to N3) are predicted to make significant contributions to these PEG-protein μ23 for the larger PEGs investigated. We conclude that for high-N3 PEGs the unfavorable excluded volume contribution to μ23 must be masked by a reduction in the unfavorable chemical contribution to μ23. We propose that this reduction occurs because of shielding of approximately quarter of the monomer residues of a PEG flexible coil from interactions with these proteins. In Discussion, we compare chemical interaction and excluded volume contributions to μ23 of PEG- folded protein interactions and to Δμ23 for PEG effects on DNA helix formation (changing PEG-nucleobase interactions) as a function of PEG size (N3).

Fig. 1.

PEG Size Dependence of Unfavorable PEG-BSA and PEG-Lysozyme Interactions. Values of the chemical potential derivative dμ2/dm3 (μ23, in kcal/mol per molal of PEG molecules) for interactions of PEGs with native BSA (diamonds) and lysozyme (triangles) at pH 7, plotted vs. the degree of polymerization N3. Solid lines are linear least squares fits of all 8 points (PEG 200- PEG 6000) with floated intercept. Dashed lines are fits to the higher-N3 PEG data (PEG 2000, 3000, 4000, and 6000) with floated intercept. Dotted lines are fits to the lower-N3 PEG data (PEG 200, 400, 600, 1000) with intercept fixed at the predicted value for two PEG end groups. Slopes and intercepts of solid lines for BSA with the uncertainty as 1 standard deviation (2.70 ± 0.13, 8.71 ± 8.6) and Lysozyme (1.00 ± 0.089, −9.24 ± 5.8); of dashed lines for BSA (2.94 ± 0.34, −15.3 ± 32 ) and Lysozyme (1.18 ± 0.24 , −26.9 ± 21 ); of dotted lines for BSA (3.62 ± 0.36 , −1.40) and Lysozyme (0.47 ± 0.046 , 0.10). Intercepts for dotted lines are fixed and therefore are reported without uncertainties.

Results

Chemical Potential Derivatives Quantifying Interactions of Folded Proteins with PEGs

Bhat and Timasheff 6 determined chemical potential derivatives dμprotein/dmPEG = μ23 for interactions of the PEG series from PEG 200 to PEG 6000 (component 3) with BSA and lysozyme (component 2) at pH 7 by dialysis and densimetry. PEG interactions with BSA and three other proteins were also investigated at highly acidic pH, but these μ23 values appear challenging to interpret, perhaps because of conformational changes induced by the combination of acid pH and high PEG residue concentration.

PEG μ23 values for BSA and lysozyme (Fig. 1) are large and positive, showing that these interactions are highly unfavorable. Values of μ23 for both proteins increase approximately in proportion to PEG size (N3). Slopes of best-fit lines through these data (with floated intercept) reveal that a 1 molal increase in concentration of PEG interior -CH2OCH2- residues, added as any chain-length PEG in the range investigated, increases μBSA by ~2.7 kcal/mol and μlysozyme by ~1.0 kcal/mol. Compared for any size PEG, μ23 for PEG-BSA interaction is at least three-fold larger than μ23 for PEG-lysozyme interaction. Is this difference primarily the consequence of chemical interactions with the four-fold larger area and more anionic character of the BSA surface, and/or does it arise primarily from excluded volume interactions with the five-fold larger molecular volume of BSA?

Prediction of Chemical Contributions to μ23 from Interactions of PEG with Native Protein Surface and Counterions

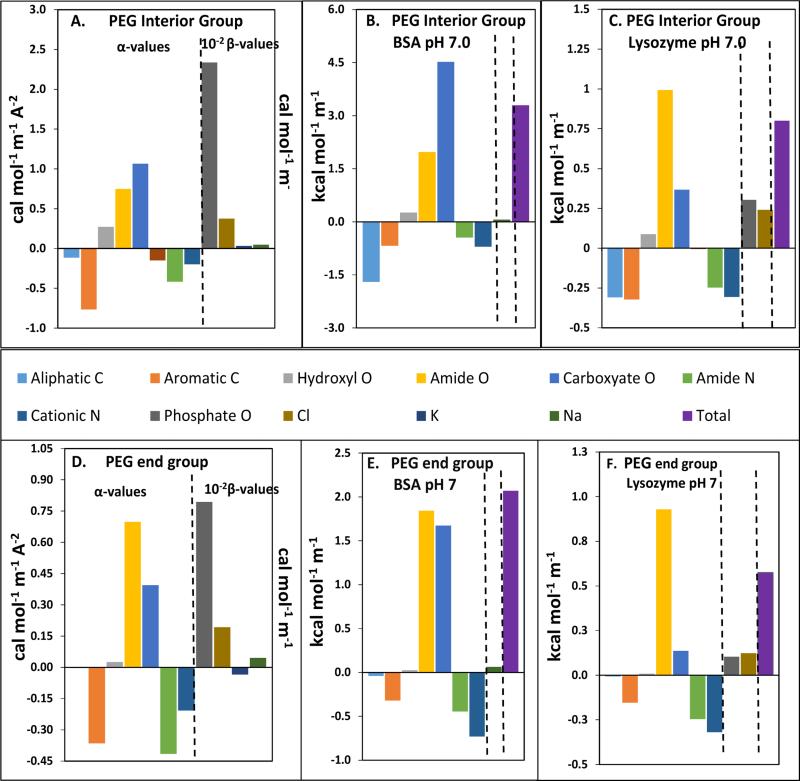

Chemical contributions μ23pi to PEG-protein interactions are predicted using recently-determined α- and β-values quantifying the interactions of interior (-CH2OCH2-) and two end (-CH2OH) groups of PEG with unit area of each protein surface type and the salt ions of the electroneutral protein component (Eq. 2, Table 1;18), together with ASA information for each type of functional group on the surface of these proteins. The α- and β-values needed for these calculations are summarized in Panels A and D of Fig 2, and ASA values are listed in Table S1.

Fig 2.

Prediction of Chemical (Preferential) Interactions of PEG Interior and End Groups with Functional Groups of Native BSA and Lysozyme. Panels A, D: Bar graph summary of interaction potentials for PEG interior group (A) and end group (D) with functional groups of protein surfaces (α values) and inorganic ions of protein component (β values; divided by 100 to put on same scale as alpha values), determined by Knowles, Shkel et al 18. Other panels: Predicted contributions to μ23 from interactions of PEG interior repeat group and end group with functional groups of BSA (left side, panels B, E) and lysozyme (left side, panels C, F) and salt ions of their minimal electroneutral components (central portion of each panel). Purple bars (right side of each panel) show predicted values of μ23pi from the sum of these protein and ion contributions.

For these predictions, we use the simplest model of the electroneutral protein component, in which only the number of salt ions needed to compensate the net charge on these proteins at pH 7 are included: (Na+)14BSA14- and lysozyme9+ (Cl,phosphate)9-. For lysozyme the anion calculation is approximate because of the uncertainty in how many of each anion are part of the electroneutral component and the unknown β-value for H2PO4−. The details of the prediction made here are in Tables S1, S2. Other models of the salt ion composition of the electroneutral protein component have been considered but are more arbitrary and appear less useful.

Comparison of Panels A and D of Fig. 2 shows that α-values for interactions of PEG interior and end groups with most protein groups are either both favorable (aromatic C, cationic N and amide N groups) or both unfavorable (amide O, carboxylate O and hydroxyl O). β-values for interactions of both types of PEG groups with inorganic salt ions are also unfavorable. An exception is aliphatic C, for which α-values are of opposite sign for interactions with interior PEG groups (favorable) and end groups (unfavorable). α- and β-Values for interactions of protein groups and ions with two PEG end groups are generally weaker that the corresponding interactions with one PEG interior group.

Predicted contributions to μ23 from chemical interactions of PEG interior and end groups with functional groups (i) on these native protein surfaces (αiASAi) and counterions () are summarized in panels B, C, E, F of Fig 2 (see also Table S1). The dominant contributions are predicted to be unfavorable interactions of interior (and end) PEG groups with amide O, carboxylate O and salt counterions, counterbalanced to an extent by favorable interactions with C and N groups.

Net-unfavorable chemical interactions of native BSA and lysozyme (including the salt ions of the component) with PEG interior groups are predicted to increase the chemical potential of BSA by 3.31 kcal mol−1 and that of lysozyme by 0.80 kcal mol−1 for an increase in concentration of PEG interior groups of 1 molal (see Table 2). PEG end group interactions are predicted to be somewhat less unfavorable: 2.07 kcal mol−1 for BSA and 0.57 kcal mol-1 for lysozyme for an increase in concentration of PEG end groups of 1 molal. These overall predictions are shown as purple bars in Fig. 2 and listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Observed and Predicted Contributions of Chemical (Preferential) Interactions (PI) and Excluded Volume (EV) to PEG-Native Protein Interactions at 25 °C a Units of all entries are kcal mol−1(molal PEG residues)−1

| Interactions of Small PEGs with: | BSA b | Lysozyme c |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical: Contribution of a PEG Interior Group | ||

| Observed d | 3.62 ± 0.36 | 0.47 ± 0.05 |

| Predicted e | 3.31 ± 0.23 | 0.80 ±0.07l |

| Chemical: Contribution of 2 PEG End Groupsf | ||

| Predicted g | 2.07 ± 0.34 | 0.57 ±0.09 l |

| Interactions of Large PEGs with: | BSA b | Lysozyme c |

|---|---|---|

| Excluded Volume, Shielded Chemical Contributions Per PEG Residue | ||

| Predicted excluded volume contribution h | 0.75 ± 0.08 | 0.44 ± 0.04 |

| Predicted reduction in chemical contribution from shielding i | −0.86 ± 0.125 | −0.21± 0.06 l |

| Comparison of Observed and Predicted μ23 Per PEG Residue | ||

| Observed j | 2.94 ± 0.34 | 1.18 ± 0.24 |

| Predicted k | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 1.03 ±0.07 l |

Uncertainty calculated as 1 standard deviation for linear least square fitting or propagated as described in [18]

Na14BSA14-

Lysozyme9+(Cl, phosphate)9-

Slope dμ23/dN3 of line fitted through the first 4 points (PEG 200- PEG 1000) of Fig 1 using predicted end-group contribution (see table) as the intercept.

Low N3 data are insufficiently accurate to obtain this from their intercept in Fig. 1 (not shown).

Calculated as with χ∞=0.74 (see text)

Slope dμ23/dN3 of dashed line on Fig. 1 (fitted through last 4 points, PEG 2000 – PEG 6000).

predicted as in footnotes g and h with χ∞=0.74. Corresponds to slope of blue line of Fig.3.

Predicted values calculated assuming the protein component is Lysozyme+9(Cl-)9 (see Tables S1, S2) are 0.59 (instead of 0.80), 0.52 (instead of 0.57), −0.19 (instead of −0.21), and 0.92 (instead of 1.03) with error reduced proportionally.

For sufficiently small PEGs, where chemical interactions entirely determine μ23, interior group interactions should predict the slope of a plot of μ23 vs. N3 – 1 and end group interactions should predict the intercept. Even though none of the PEGs investigated may be small enough for chemical interactions to be the only significant determinant of μ23 (19; also see Fig 4 and 5 below and accompanying text), Table 2 shows quite good agreement between predicted (above) and observed interior PEG group interactions with both BSA and lysozyme: 3.31 kcal/mol (predicted) vs. 3.6 kcal/mol (observed) for BSA; 0.80 kcal/mol (predicted) vs. 0.47 kcal/mol (observed) for lysozyme. “Observed” values are obtained from the slopes of plots of μ23 vs. N3 for the four smallest PEGs investigated (PEG 200-PEG 1000) with intercepts fixed at the predicted PEG end group interaction (Fig 1; Table 2). Scatter in these low-N3 interaction data makes it impractical to float the intercepts in these fits. Similar estimates of observed PEG residue-protein interaction values are obtained from the slopes of plots of μ23 vs. N3 for all eight PEGs investigated (PEG 200-PEG 6000): 2.7 kcal/mol (BSA) and 1.0 kcal/mol (lysozyme).

Figure 5.

Dissection of PEG-DNA Interactions into Contributions from Chemical Interactions, Shielding, and Excluded Volume Effects. Panel A : PEG-Duplex m-values (Δμ23) . Panel B; PEG-Hairpin m-values (Δμ23). Red lines are predicted contributions of unshielded preferential (chemical) interactions (PI) to Δμ23 calculated using observed lower-N3 (EG-triEG) slopes from Figure 4B. Purple lines are predicted excluded volume (EV) contributions to Δμ23 of higher-N3 PEGs (≥PEG1450). Green lines are reduction due to shielding of chemical (preferential) interaction contributions ((1-χ)PI) for a residue-accessibility factor χ = 0.6 (see Table 3). Blue lines are predicted combinations of shielded chemical and excluded volume contributions (χPI+EV) to Δμ23 for higher-N3 PEGs (≥PEG1450). Dashed black lines are sums of excluded volume (purple) and unshielded chemical (red) contributions (PI+EV).

Predicted chemical contributions to protein interactions with any size PEG (before correction for shielding (χ) effects, if necessary) are:

| (Eq. 6) |

where the units of μ23pi are kcal mol−1 molal−1. Uncertainties in these values are reported in Table 2. These predicted values of μ23pifor any size PEG are plotted vs N3 – 1 in Fig. 3 as the red lines. Contributions of the constant terms in Eq. 6 (the predicted differences between interactions of internal and end PEG groups with these proteins) are small even for PEG 200 (tetraEG) and negligible (given the experimental uncertainty) for larger PEGs. Hence μ23pi is predicted to be approximately proportional to N3 (also to N3 – 1) for larger PEGs, as the red curves in Fig 3 indicate.

Figure 3.

Dissection of Unfavorable PEG-Protein Interactions into Contributions from Chemical Interactions, Shielding, and Excluded Volume Effects. Panel A : PEG-BSA interactions. Panel B; PEG-lysozyme interactions. Data points are the same as in Fig. 1 plotted vs N3-1. Red lines are predicted contributions of unshielded preferential (chemical) interactions (PI) to μ23 from Eq. (2) using α- and β-values from Fig. 218 and ASA information from Table S1. Purple lines are predicted excluded volume (EV) contributions to μ23 of higher-N3 PEGs (≥PEG2000). Green lines are reduction due to shielding of chemical (preferential) interactions ((1-χ)PI) for a residue-accessibility factor χ = 0.74 (see Table 2). Blue lines are predicted combinations of shielded chemical and excluded volume contributions (χPI+EV) to μ23 for higher-N3 PEGs (≥PEG2000). Dashed black lines are sums of excluded volume (purple) and unshielded chemical (red) contributions (PI+EV).

One interpretation of the finding that predicted μ23pi values for chemical PEG-protein interactions are in near-quantitative agreement with experimental results, not only for the smaller PEGs investigated but for larger PEGs as well, would be that neither chemical shielding (χ) effects nor excluded volume effects of large PEGs make significant contributions to the observed linear dependence of μ23 on N3. However, predictions of the excluded volume contribution indicate a different interpretation: excluded volume effects are significant for interactions of both proteins with larger N3 PEGs, but the unfavorable contribution of excluded volume effects to μ23 is largely offset and therefore masked by a reduction in unfavorable chemical interactions because of shielding of interactions of PEG residues in the interior of a PEG flexible coil with these proteins. These predictions are developed in the following section.

Predicting Excluded Volume Contributions to μ23 for Interactions of Large PEGs with Proteins

Equations derived by Hermans20 to predict the excluded volume between a flexible-coil polymer like high-N3 PEG and a spherical protein or cylindrical DNA oligomer are summarized in Eqs. 3 and 4 (Table 1). These successfully predict the functional form and magnitude of the unfavorable (stabilizing) excluded volume contribution to PEG m-values for DNA oligomer melting, where m-value = Δμ23 (19; see Table 3 below) The key prediction of this analysis is that excluded volume contributions to the μ23 terms that contribute to PEG molal m-values are proportional to N3 at high N3 (Eqs. 3-4, Table 1). Using a statistical segment length (Kuhn length) LK =12.6 A and modeling lysozyme and BSA as spheres of radii 15.8 A and 27.0 A, respectively, we predict the following excluded volume effects for high-N3 PEGs (Table 2; see Supplemental):

| Eq 7 |

Unfavorable excluded volume contributions μ23ev (Eq. 7), plotted in Figure 3 (purple lines), are approximately 25% (BSA) to 50% (lysozyme) as large as the corresponding chemical contributions μ23pi at any large N3.

Table 3.

Contributions from Chemical (Preferential) Interactions (PI) and Excluded Volume (EV) to PEG Effects on DNA Duplex and Hairpin Melting. Units of all entries are kcal mol−1molal PEG residues)−1

| 12 bp Duplex a,b | 4 bp Hairpin a,b | |

|---|---|---|

| Observed PEG-DNA Chemical Interaction Per PEG Residuec | −0.322 ± 0.02 | −0.160 ± 0.02 |

| Predicted excluded volume effect Per PEG Residued | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.058 ± 0.006 |

| Predicted reduction in PEG-DNA chemical interaction from shielding e | 0.129 ± 0.02 | 0.064 ± 0.01 |

| Observed, Predicted PEG Effects Per PEG Residue | ||

| Observed f | 0.168 ± 0.01 | −0.033 ± 0.003 |

| Predicted g | 0.164 ± 0.037 | −0.0346 ± 0.013 |

Data obtained at 40 °C.

Uncertainty calculated as 1 standard deviation for linear least square fitting or propagated as described in [18]

Slope dΔμ23/dN3 of line fitted through the first 3 points (EG - triEG) of Fig 4B and red lines of Fig.5.

Calculated as with χ∞=0.6 (see text)

Slope dΔμ23/dN3 of dashed line on Fig. 4C (fitted through last 4 points, PEG 2000 – PEG20000, for duplex and last 5 points, PEG 1450 – PEG20000, for hairpin).

predicted as in footnotes d and e with χ∞=0.6. Corresponds to slope of blue line of Fig.5.

The sum of chemical and excluded volume interactions μ23pi + μ23ev (from eqs. 6 and 7), plotted as dotted lines in Fig 3, clearly predicts too unfavorable a PEG-protein interaction to be consistent with the experimental data. This lack of agreement between prediction and experiment for high-N3 PEGs indicates that the predicted contribution of chemical interactions to μ23 for high-N3 PEGs is too large. A reduction in this chemical contribution for high-N3 PEGs was proposed previously 19, based on the expectation that a fraction (1–χ) of PEG residues in the interior of PEG flexible coils are inaccessible to these proteins. This shielded fraction (1–χ) has not yet been investigated by theory or simulations, and its dependence on PEG N3 and protein size is unknown. Here we treat it as a constant (χ∞) to be determined by comparison of predicted and observed values of μ23 for high-N3 PEG. From the DNA 12-mer analysis (Supplemental and Table 3 below), we find χ∞ = 0.6 ±0.06 (i.e. 40% of PEG residues are inaccessible to the 12-mer DNA oligomers). For lysozyme and BSA, a somewhat larger χ∞ = 0.74 provides a better fit to the experimental data, as summarized in Table 2. Fig. 3 plots (1 – χ∞) μ23pi, the reduction in μ23pi from this shielding effect, vs N3 – 1 and shows that for both proteins this reduction in μ23pi is comparable in magnitude to μ23ev.

With χ = 0.74 we obtain for high-N3 PEGs:

| Eq. 8 |

where the units of μ2 are kcal mol−1 molal−1. The intercepts in Eq. 8 are negligible for high-N3 PEGs. If χ∞ is independent of N3 then Eq. 8 predicts that μ23 is proportional to N3 for high-N3 PEGs. These predicted μ23 values are plotted in Figure 3 (blue lines) and clearly are a reasonable fit to the high-N3 PEG data, with a slope which is not very different from that of the low-N3 PEG data.

For lysozyme, unfavorable chemical interactions of accessible PEG residues and excluded volume effects are each predicted to account for half of the unfavorable effect of high-N3 PEGs on the chemical potential of BSA. The observed result is μ23= 1.18 N3, which agrees with the prediction (μ23 = 1.03 N3) within 10-15% for this choice of χ∞.

For BSA unfavorable chemical interactions of accessible PEG residues are predicted to account for approximately two-thirds, and excluded volume one-third, of the PEG effect on the chemical potential of BSA. The experimental result is μ23 = 2.94 N3, in agreement with the prediction (μ23 = 3.2 N3) within 5-10% for this choice of χ∞.

We conclude that the thermodynamic consequences for PEG-protein interactions of linking PEG residues together to form a high-N3 chain polymer (excluded volume and shielding effects of PEG flexible coils) are largely compensating at the level of μ23.

Discussion

Comparisons of Chemical, Excluded Volume Contributions to PEG-Protein Interactions and to PEG Effects on Duplex and Hairpin DNA Melting: Determining When Excluded Volume Effects are Most Important

Here we compare results and conclusions of the present study of chemical and excluded volume contributions to PEG-native protein interactions with previous analysis of chemical and excluded volume contributions to PEG m-values for melting of duplex and hairpin DNA oligomer helices. PEG m-values for oligomer DNA melting are equal to differences in μ23 between the melted strand(s) and the helix (m-value = Δμ23 , where from Eq. 5 Δμ23 = Δχμ23pi + Δμ23ev). This parallels the analysis of PEG-native protein interactions, quantified by values of μ23 where μ23 = χμ23pi + μ23. In both cases, the shielding factor χ ≈ 1 and μ23ev ≈ 0 for sufficiently small-N3 PEGs, and χ = χ∞ for high-N3 PEGs. (For simplicity, the same χ∞ is used for helix and melted strands.)

The chemical term Δμ23pi for DNA melting is interpreted by analogy with Eq. 2 as the sum of interactions of the interior and end groups of PEG with the nucleobase ASA exposed in melting19. The excluded volume term Δμ23ev is the difference in excluded volume interactions with the melted strand(s) and the double helix; this term is particularly significant for duplex melting where two strands are formed from one.

Experimentally, μ23 values for PEG-native protein interactions are linear functions of N3 (approximately proportional to N3) for both low- and high-N3 PEGs, with positive slopes that are sufficiently similar that all eight PEG μ23 values for each protein can be fit by a single line over the range of N3 investigated (Fig. 1). Predictions of μ23pi and μ23ev in table 2 and Fig. 3 show that both are proportional to N3 at high N , and that μ23pi is a linear function of (nearly proportional to) N3 at low N3. Both μ23pi and μ23ev are positive (unfavorable).

Paralleling this behavior of PEG-protein interactions, panels B and C of Fig. 4 show that PEG m-values = Δμ23 for duplex and hairpin melting also are linear functions of N3 (approximately proportional to N3) for both low- and high-N3 PEGs. (These experimental data were originally reported as monomolal PEG m-values (i.e. Δμ23/N3), which to a good approximation are independent of N3 at both small and large N3 (see Figure 4A).) Comparison of Fig 4 B, C with Fig. 1 shows a key difference between the low-N3 PEG-protein and PEG-DNA data. PEG-DNA Δμ23 values are negative for EG, and become increasing negative with increasing N3 between EG and tetraEG by - 0.32 kcal mol−1 (molal PEG residues)−1 for duplex and - 0.16 kcal mol−1 (molal PEG residues)−1 for hairpin. Therefore chemical interactions between PEG residues and the DNA nucleobase surface exposed in melting are favorable, while chemical interactions of PEGs with native BSA and lysozyme are unfavorable (Fig.2, Table 2). The two-fold difference in PEG effects for 12-bp duplex vs 12-mer hairpin melting is consistent with the ratio of ΔASA of melting for duplex and hairpin, and supports the interpretation of these effects as purely chemical interactions.

In the vicinity of tetraEG, PEG-DNA Δμ23 values exhibit a minimum for duplex DNA melting and increase for larger-N3 PEGs, becoming positive and again approximately proportional to N3 for N3 > 10. For hairpin melting, PEG-DNA Δμ23 values decrease less rapidly with increasing N3 above tetraEG. PEG effects on duplex and hairpin melting in these low- and high-N3 regions are summarized in Table 3. Since the smallest PEG studied with native BSA and lysozyme was PEG200 (tetraEG), it is possible that these PEG effects are not purely from chemical interactions.

Predictions of excluded volume contributions (Δμ23ev) of high N3 PEGs on duplex and hairpin melting in Table 3 and Fig. 5 A,B (analogous to Fig 3) show that these quantities are positive (unfavorable; helix stabilizing) and proportional to N3. The predicted excluded volume effect is much larger for duplex melting (0.34 kcal mol−1 (molal PEG residues)−1) than for hairpin melting (0.058 kcal mol−1 (molal PEG residues)−1) primarily because of the stoichiometry of duplex melting, forming two strands from one duplex.

The behavior of Δμ23 for DNA melting as a function of PEG N3 at high PEG N3 predicted from Δμ23pi + Δμ23ev (dotted lines in Fig 4 D, E) agrees qualitatively but not quantitatively with the observed Δμ23 . We attributed the difference to shielding of a fraction (1- χ∞) of PEG residues in the interior of PEG flexible coils, reducing the per-residue interaction of PEG with DNA 19. Table 3 and Fig 5 A, B show that quantitative agreement is obtained for χ∞ ≈ 0.6 (blue lines on Fig. 5), similar to the best fit value for PEG-protein interactions (χ∞ ≈ 0.74).

Comparison with Other Interpretations of PEG Interactions, PEG Effects

Previous analyses of PEG interactions and/or PEG effects on protein or nucleic acid processes have generally interpreted these either as primarily excluded volume effects, as the complete-exclusion (osmotic) limit of a chemical effect, or by other mechanisms5,6,13,21-27. The PEG-protein interactions summarized in Figure 1 were originally interpreted as a steric (excluded volume) effects 6. An insightful review pointed out that PEG-protein interaction and PEG effects on protein processes should not be interpreted simply as excluded volume effects because of its chemical interactions with proteins13. Here we separate and quantify these effects based on additivity (Eq. 1). Some previous analyses of chemical interaction and excluded volume effects of solutes on biopolymer conformational transitions (protein folding) have also been based on additivity of these contributions to the m-value (Δμ23). In these studies, chemical interactions of the solute with the protein were evaluated empirically from experimental m-values and predictions of solute-protein excluded volume contributions28-30. A recent detailed experimental study of polyol m-values for unfolding of a beta-hairpin found large, compensating enthalpic and entropic contributions to the smaller-magnitude free energy m-value, consistent with a major role of chemical interactions in determining these m-values 31-33. Here we determine chemical interactions from small compound data 18, and calculate excluded volume interactions of large PEGs with proteins and nucleic acids using Hermans’ theory20.

The analysis of effects of the entire PEG series on DNA helix formation (Fig 5; see also Knowles et al19) shows that both chemical and excluded volume contributions are significant for larger PEG oligomers (N3 > 4) and polymers, especially where the process involves a change in molecularity (e.g. duplex to 2 ss). Where only a change in shape is involved, as for hairpin DNA melting, we find (and predict) that excluded volume effects are much smaller in magnitude.

We conclude that chemical interactions of PEGs with proteins and nucleic acids make significant contributions to μ23 or Δμ23 (i.e. m-values) for all PEG sizes. Knowles et al 19 deduced that chemical interactions are the only significant contributor to m-values for effects of tetra EG or smaller PEGs on nucleic acid helix formation. Knowles et al 18 demonstrated that an interpretation based entirely on chemical interactions is sufficient to interpret μ23 values for the interactions of tetraEG and glycerol with a variety of small model compounds. These findings are consistent with previous analyses of the effects of urea on nucleic acid helix formation 34, and effects of urea, glycine betaine, proline and other small solutes on protein folding 35-38. Likewise an interpretation based entirely on chemical interactions is sufficient to interpret μ23 values for the interactions of urea, proline and glycine betaine with a variety of small model compounds34,36-38.

Chemical interactions play a major role in both PEG-native protein interactions and PEG effects on DNA melting for even the largest PEGs investigated (PEG20000 in DNA melting studies, PEG6000 in studies with native proteins). These chemical interactions differ greatly from favorable to unfavorable for different functional groups. For both native proteins and the DNA melting processes studied, we deduce that chemical interactions per PEG residue are reduced for high-N3 PEGs by shielding of a moderate fraction of PEG residues (one-quarter and one-third for these examples), presumably those deep in the interior of the PEG flexible coil. Both chemical and excluded volume effects of PEG are found to be proportional to PEG size (N3) for high-N3 PEGs, and chemical effects of PEG are also proportional to N3 for low-N3 PEGs. The analysis developed and applied in this and two previous papers18,19 provides a general method to separate and interpret chemical (PI, χ) and excluded volume interactions of all PEGs with biopolymers, as well as chemical and excluded volume effects of all PEGs on any biopolymer process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Rituparna Sengupta for calculations of accessible surface area of functional groups for lysozyme. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 47022 (to M.T.R.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bloomfield VA, Crothers DM, Tinoco I. Physical chemistry of nucleic acids. Harper & Row; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crothers DM, Tinoco I, Bloomfield VA. Nucleic acids : structures, properties, and functions. University Science Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asenjo JA, Andrews BA. Aqueous two-phase systems for protein separation: A perspective. J. Chromatogr. A. 2011;1218:8826–8835. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.06.051. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2011.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finet S, Vivares D, Bonnete F, Tardieu A. Controlling biomolecular crystallization by understanding the distinct effects of PEGs and salts on solubility. Methods Enzymol. 2003;368:105–129. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)68007-9. doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(03)68007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atha DH, Ingham KC. Mechanism of precipitation of proteins by polyethylene glycole - analysis in terms of excluded volume. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:2108–2117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhat R, Timasheff SN. Steric Exclusion Is the Principal Source of the Preferential Hydration of Proteins in the Presence of Polyethylene Glycols. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1133–1143. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560010907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer RM, Shende VR, Motl N, Pace CN, Scholtz JM. Toward a molecular understanding of protein solubility: increased negative surface charge correlates with increased solubility. Biophysical journal. 2012;102:1907–1915. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.01.060. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2012.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahadevan H, Hall CK. Experimental analysis of protein precipitation by polyethylene-glycol and comparison with theory. Fluid Phase Equilib. 1992;78:297–321. doi:10.1016/0378-3812(92)87043-m. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middaugh CR, Tisel WA, Haire RN, Rosenberg A. Determination of the apparent thermodynamic activities of saturated protein solutions. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:367–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rytting E, Lentz KA, Chen XQ, Qian F, Venkatesh S. Aqueous and cosolvent solubility data for drug-like organic compounds. Aaps Journal. 2005;7:E78–E105. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070110. doi:10.1208/aapsj070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elcock AH. Models of macromolecular crowding effects and the need for quantitative comparisons with experiment. Current opinion in structural biology. 2010;20:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.01.008. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parsegian VA, Rand RP, Rau DC. Osmotic stress, crowding, preferential hydration, and binding: A comparison of perspectives. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:3987–3992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.3987. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.8.3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou HX, Rivas G, Minton AP. Macromolecular crowding and confinement: biochemical, biophysical, and potential physiological consequences. Annual review of biophysics. 2008;37:375–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125817. doi:10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knoll D, Hermans J. Polymer-protein interactions - comparison of experiment and excluded volume theory. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:5710–5715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozer N, Kuttner YY, Haran G, Schreiber G. Protein-protein association in polymer solutions: From dilute to semidilute to concentrated. Biophysical journal. 2007;92:2139–2149. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097717. doi:10.1529/biophysj.106.097717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee LL, Lee JC. Thermal stability of proteins in the presence of poly(ethylene glycols). Biochemistry. 1987;26:7813–7819. doi: 10.1021/bi00398a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillip Y, Sherman E, Haran G, Schreiber G. Common Crowding Agents Have Only a Small Effect on Protein-Protein Interactions. Biophysical journal. 2009;97:875–885. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.026. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowles DB, et al. Chemical Interactions of Polyethylene Glycols (PEG) and Glycerol with Protein Functional Groups: Applications to PEG, Glycerol Effects on Protein Processes. Submitted to Biochemistry. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knowles DB, LaCroix AS, Deines NF, Shkel I, Record MT. Separation of preferential interaction and excluded volume effects on DNA duplex and hairpin stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:12699–12704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103382108. doi:10.1073/pnas.1103382108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermans J. Excluded-Volume Theory of Polymer Protein Interactions Based on Polymer-Chain Statistics. J Chem Phys. 1982;77:2193–2203. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupuis NF, Holmstrom ED, Nesbitt DJ. Molecular-crowding effects on single- molecule RNA folding/unfolding thermodynamics and kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:8464–8469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316039111. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316039111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knoll DA, Hermans J. Effect of poly(ethylene glyol) on protein denaturation and model compound pKa 's. Biopolymers. 1981;20:1747–1750. doi:10.1002/bip.1981.360200814. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakano S, Hirayama H, Miyoshi D, Sugimoto N. Dimerization of Nucleic Acid Hairpins in the Conditions Caused by Neutral Cosolutes. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:7406–7415. doi: 10.1021/jp302170f. doi:10.1021/jp302170f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spink CH, Garbett N, Chaires JB. Enthalpies of DNA melting in the presence of osmolytes. Biophys. Chem. 2007;126:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.07.013. doi:10.1016/j.bpc.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buscaglia R, et al. Polyethylene glycol binding alters human telomere G-quadruplex structure by conformational selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:7934–7946. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt440. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarvis TC, Ring DM, Daube SS, von Hippel PH. Macromolecular crowding - thermodynamic consequence for prottein-protein interactions within the T4 DNA-replication complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:15160–15167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmerman SB, Harrison B. Macromolecular crowding accelerates the cohesion of DNA fragments with complementary termini. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:2241–2249. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.7.2241. doi:10.1093/nar/13.7.2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis-Searles PR, Saunders AJ, Erie DA, Winzor DJ, Pielak GJ. Interpreting the effects of small uncharged solutes on protein-folding equilibria. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 2001;30:271–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.271. doi:10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saunders AJ, Davis-Searles PR, Allen DL, Pielak GJ, Erie DA. Osmolyte- induced changes in protein conformation equilibria. Biopolymers. 2000;53:293–307. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(20000405)53:4<293::AID-BIP2>3.0.CO;2-T. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0282(20000405)53:4<293::aid-bip2>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schellman JA. Protein stability in mixed solvents: A balance of contact interaction and excluded volume. Biophysical journal. 2003;85:108–125. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74459-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sapir L, Harries D. Is the depletion force entropic? Molecular crowding beyond steric interactions. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;20:3–10. doi:10.1016/j.cocis.2014.12.003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sapir L, Harries D. Origin of Enthalpic Depletion Forces. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:1061–1065. doi: 10.1021/jz5002715. doi:10.1021/jz5002715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Politi R, Harries D. Enthalpically driven peptide stabilization by protective osmolytes. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:6449–6451. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01763a. doi:10.1039/c0cc01763a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guinn EJ, et al. Quantifying Functional Group Interactions That Determine Urea Effects on Nucleic Acid Helix Formation. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ja400965n. doi:10.1021/ja400965n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auton M, Rösgen J, Sinev M, Holthauzen LMF, Bolen DW. Osmolyte effects on protein stability and solubility: A balancing act between backbone and side-chains. Biophys. Chem. 2011;159:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2011.05.012. doi:10.1016/j.bpc.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Capp MW, et al. Interactions of the osmolyte glycine betaine with molecular surfaces in water: thermodynamics, structural interpretation, and prediction of m-values. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10372–10379. doi: 10.1021/bi901273r. doi:10.1021/bi901273r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diehl RC, Guinn EJ, Capp MW, Tsodikov OV, Record MT., Jr. Quantifying Additive Interactions of the Osmolyte Proline with Individual Functional Groups of Proteins: Comparisons with Urea and Glycine Betaine, Interpretation of m-Values. Biochemistry. 2013 doi: 10.1021/bi400683y. doi:10.1021/bi400683y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guinn EJ, Pegram LM, Capp MW, Pollock MN, Record MT. Quantifying why urea is a protein denaturant, whereas glycine betaine is a protein stabilizer. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16932–16937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109372108. doi:DOI 10.1073/pnas.1109372108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.