Abstract

Astrocytes are major supportive cells in brains with important functions including providing nutrients and regulating neuronal activities. In this study, we demonstrated that astrocytes regulate amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing in neuronal cells through secretion of group IIA secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2-IIA). When astrocytic cells (DITNC) were mildly stimulated with the pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF α and IL-1β, sPLA2-IIA was secreted into the medium. When conditioned medium containing sPLA2-IIA was applied to human neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cells, there was an increase in both cell membrane fluidity and secretion of α-secretase-cleaved soluble amyloid precursor protein (sAPPα). These changes were abrogated by KH064, a selective inhibitor of sPLA2-IIA. In addition, exposing SH-SY5Y cells to recombinant human sPLA2-IIA also increased membrane fluidity, accumulation of APP at the cell surface, and secretion of sAPPα, but without altering total expressions of APP, α-secretases and β-site APP cleaving enzyme (BACE1). Taken together, our results provide novel information regarding a functional role of sPLA2-IIA in astrocytes for regulating APP processing in neuronal cells.

Keywords: cytokine, astrocytes, sPLA2-IIA, sAPPα, membrane fluidity, SH-SY5Y

INTRODUCTION

Astrocytes are multifunctional house-keeping cells playing important roles in regulating the environment within which neurons function (Nedergaard et al., 2003; Pereira and Furlan, 2010). These cells are known to control local ion and pH homeostasis, provide glucose, deliver metabolic substrates, maintain blood–brain barrier, and remove neuronal waste. In many instances, astrocytes modulate neuronal activities by means of release of signaling molecules, including glutamate, D-serine, and adenosine. They also regulate neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and synaptic activity, although the underlying mechanism(s) remain to be elucidated.

Phospholipases A2 (PLA2s) are ubiquitous enzymes responsible for maintenance of phospholipid homeostasis in cell membranes. There are three major types of PLA2s, namely, cytosolic PLA2, (cPLA2), calcium-independent PLA2 (iPLA2), and secretory PLA2 (sPLA2) (Sun et al., 2004). sPLA2 are low molecular weight proteins with more than 12 subtypes present in a wide variety of cells and venoms. One of the subtypes, the group IIA sPLA2 (sPLA2-IIA) has been identified in astrocytes (Lin et al., 2004) and is known to modulate neuronal functions, including calcium influx and apoptosis (Morioka et al., 2002; Yagami et al., 2003, 2014). sPLA2-IIA also has antibacterial functions (Harwig et al., 1995; Weinrauch et al., 1996) and increased production has been linked to inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Hurt-Camejo et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2004, 2007; Jia et al., 2005; Moses et al., 2006). In cell culture systems, upregulation of sPLA2-IIA mRNA expression has been shown in astrocytes stimulated with pro-inflammatory cytokines, processes that activate the NF-κB pathway (Li et al., 1999; Wang and Sun, 2000; Jensen et al., 2009). Using non-specific PLA2 inhibitors, Cho et al. (2006) showed that PLA2s affect the proteolytic process of amyloid precursor protein (APP), which produces either neurotoxic amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) (Vassar, 2004) or neurotrophic and neuroprotective α-secretase-cleaved soluble APP (sAPPα) (Esch et al., 1990; Allinson et al., 2003; Thornton et al., 2006). In our previous study, we showed that group III sPLA2 (sPLA2-III) from bee venom increased sAPPα production through altering membrane fluidity (Yang et al., 2010). sPLA2-IIA has been shown to effect various processes associated with neuroinflammatory diseases such as arthritis and atherosclerosis (Touqui and Alaoui-El-Azher, 2001; Niessen et al., 2003). Furthermore, sPLA2-IIA has been shown to be upregulated in the astrocytes of AD patients which directly implicates sPLA2-IIA in AD pathogenesis (Moses et al., 2006). Taken together, the aforementioned processes of sPLA2-IIA and its increased presence around Aβ plaque sites within the brains of AD patients need to be further understood to offer insights into AD etiology.

In this study, we explored the effects of sPLA2-IIA secreted from cytokine-stimulated immortalized rat astrocytes (DITNC) on membrane integrity, APP processing and sAPPα secretion in human neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y). Specifically, we demonstrated that TNFα and IL-1 β can induce DITNC cells to secret sPLA2-IIA into the conditioned medium, which in turn, altered membrane fluidity and sAPPα secretion in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. In order to further verify the role of sPLA2-IIA in sAPPα secretion, we tested the effects of a recombinant human sPLA2-IIA on sAPPα secretion, membrane fluidity, the recruitment of APP to the cell surface, and the expressions of α-secretases, and β-site APP cleaving enzyme (BACE1) in SH-SY5Y cells. AD is associated with chronic inflammation and this study demonstrates that upregulation of sPLA2-IIA in astrocytes influences neuronal membrane properties and APP metabolism. Here we present novel information to better understand the role of cytokine-stimulated astrocyte secretion of sPLA2-IIA and its subsequent effects in neurons.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and reagents

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with high glucose, DMEM/F12 medium (1:1), Ham’s F-12 medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Recombinant human sPLA2-IIA was from BioVendor (Candler, NC, USA). Selective sPLA2-IIA inhibitor (KH064) was from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA). Cytokines including TNFα and IL-1β were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and all-trans retinoic acid (RA) were from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Farnesyl-(2-carboxy-2-cyanovinyl)-julolidine (FCVJ) was from Dr. Haidekker’s Laboratory (University of Georgia) (Nipper et al., 2008).

Cell culture

SH-SY5Y cells (1.0 × 105 cells/well) (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were seeded into 12-well plates or 60-mm dishes (1.0 × 106 cells/dish) and were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (1:1) containing 10% FBS. For differentiation, SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to 10 μM RA for 6 days with changes of fresh culture medium every 2 d. The rat immortalized astrocytes (DITNC) were obtained from ATCC and cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS. All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

Cell viability by MTT test

Cell viability was determined by MTT reduction. Briefly, differentiated SH-SY5Y cells cultured in 12-well plates were treated with different concentrations of sPLA2-IIA. After treatment, the medium was removed and 1 ml of MTT reagent (0.5 mg/ml) in DMEM was added into each well. Cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C and after dissolving formazan crystals with DMSO, absorbance at 540 nm was measured.

Characterization of membrane fluidity by fluorescence microscopy of FCVJ-labeled cells

A fluorescent molecular rotor, farnesyl-(2-carboxy-2-cyanovinyl)-julolidine (FCVJ) was used to measure the relative membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells. FCVJ was designed to be a membrane-compatible fluorescent molecular rotor (Haidekker et al., 2001) with the quantum yield strongly dependent on the local free volume. A higher fluorescent intensity of FCVJ reflects the intramolecular-rotational motions being restricted by a smaller local free volume, indicating a more viscous membrane. On the other hand, a lower fluorescent intensity of FCVJ reflects a lower viscous and a more fluidized membrane. Previously, we have verified the application of FCVJ for measuring membrane fluidity by comparing results obtained using FCVJ with those from the technique of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) (Nipper et al., 2008). In this study, we adapted the protocol from Haidekker et al. (2001) to fluorescently label cells with FCVJ. Briefly, after treatment with sPLA2-IIA or conditioned medium from DITNC cells, SH-SY5Y cells were washed with PBS and incubated in DMEM containing 20% FBS and 1 μM FCVJ for 20 min. Excess FCVJ was removed by washing cells with PBS three times. Fluorescent intensity measurements were performed at room temperature using a Nikon TE-2000 U fluorescence microscope with an oil immersion 60× objective lens. Images were acquired using a cooled-CCD camera controlled by a computer running a MetaVue imaging software (Universal Imaging, PA, USA). The fluorescent intensities of FCVJ per cell area were measured. Background subtraction was done for all images prior to data analysis.

Treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with conditioned medium from DITNC astrocytes

DITNC astrocytes were exposed to cytokines (TNFα and IL-1β, 10 ng/ml) for 8 h. Cytokines were then removed, and the cells were incubated in serum-free medium for another 40 h. The same volume of conditioned medium from control and cytokine-stimulated cells was used for Western blot analysis of sPLA2-IIA. Alternatively, the conditioned medium from control and cytokine-stimulated DITNC cells were applied to SH-SY5Y cells for 24 h. In order to demonstrate the effects of sPLA2-IIA in the conditioned medium on sAPPα secretion and membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells, (S)-5-(4-(benzyloxy)phenyl)-4-(7-phenylheptanamido)pentanoic acid (KH064), a selective sPLA2-IIA inhibitor (1 μM), was added to the conditioned medium prior to applying to SH-SY5Y cells. KH064 has been used as a potent sPLA2-IIA inhibitor previously (Gregory et al., 2006).

Western blot analysis of sPLA2-IIA released from DITNC astrocytes and sAPPα released from SH-SY5Y cells

After treating DITNC astrocytes with cytokines, conditioned medium was used for Western blot analysis for sPLA2-IIA. After treating SH-SY5Y cells with conditioned media, or recombinant human sPLA2-IIA, culture media were collected for measurement of sAPPα. β-actin in cell lysate was the internal standard. The collected medium was centrifuged at 12,000g for 5 min to remove cell debris, and the same volume of medium from each sample (e.g., 40 μl) was diluted with Laemmli buffer, boiled for 5 min, subjected to electrophoresis in 7.5% SDS–polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST) and were incubated overnight at 4 °C in 3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) with 0.02% (w/v) sodium azide in TBST with a 6E10 monoclonal antibody (1:1000 dilution; Millipore, Billerica, MA) that recognizes residues 1–17 of the Aβ domain of human sAPPα or with anti-sPLA2-IIA rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:1000; BioVendor, Candler, NC). Membranes were washed three times during a 15-min period with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody or goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:2000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) in 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in TBST at room temperature for 1 h. After washing with TBST for three times, the membrane was subjected to SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent detection reagents from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA) to visualize bands. The protein bands detected on X-ray film were quantified using a computer-driven scanner and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Western blot analysis of APP, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM17 and BACE1 in SH-SY5Y cells

After treatments, the protein concentration of the SH-SY5Y cell lysate was determined by BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Equivalent amounts of protein from each sample (e.g., 30 μg) was diluted with Laemmli buffer, boiled for 5 min, subjected to electrophoresis in 7.5% SDS–polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST) and were incubated overnight at 4 °C in 3% (w/v) BSA with 0.02% (w/v) sodium azide in TBST with 6E10 monoclonal antibody, anti-ADAM9 antibody (1:1000 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-ADAM10 antibody (1:1000 dilution; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), anti-ADAM17 antibody (1:1000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or anti-BACE1 antibody (1:1000 dilution; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Membranes were washed three times during a 15-min period with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:2000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) in 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in TBST at room temperature for 1 h. After washing with TBST for three times, the membrane was subjected to SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent detection reagents from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA) to visualize bands. The protein bands detected on X-ray film were quantified using a computer-driven scanner and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Immunofluorescent staining and assessment of APP at the cell surface of SH-SY5Y cells

SH-SY5Y cells were plated onto cover slips and after differentiation and treatments, they were fixed in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde without prior permeabilization with detergent in a similar manner as previously reported (Yang et al., 2009, 2010). After washing three times with PBS, nonspecific binding of antibodies was blocked by 5% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C in 3% goat serum with anti-APP mouse antibody (1:200 dilution; assay designs, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) that recognizes the N-terminus of APP. The cover slips were washed with PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:400, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and washed with PBS. Cover slips were then mounted and fluorescent intensity measurements were performed at room temperature using the Nikon TE-2000 U fluorescence microscope and oil immersion 60× objective lens. Images were acquired using a CCD camera controlled by a computer running a MetaVue imaging software (Universal Imaging, PA, USA). The fluorescent intensities per cell area were measured. Background subtraction was done for all images prior to data analysis.

Quantification of Aβ1–42

After treatments, culture medium and cell lysates were collected, supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail and conditioned medium was centrifuged at 12,000g for 5 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris. An aliquot (100 μl) of the supernatant was used for Aβ 1–42 quantification using an ELISA kit specific for Aβ1–42 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following manufacturer’s recommendation. According to the instruction manual, Aβ1–12, Aβ1–20, Aβ12–28, Aβ22–35, Aβ1–40, Aβ1–43, Aβ42–1 and APP show no cross-reactivity. The minimum detectable dose of Aβ1–42 is <1.0 pg/ml. The level of Aβ1–42 in each sample was measured in duplicates and expressed in pg/ml.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. Comparison between two groups was made with student’s t test. Comparisons of more than two groups were made with an one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc tests. Values of p < 0.05 are considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

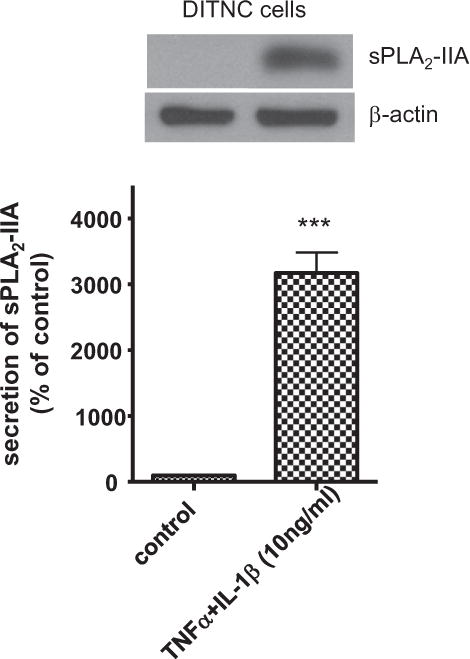

Secretion of sPLA2-IIA from cytokine-stimulated DITNC astrocytes

It has been shown that when stimulated by cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β, DITNC astrocytes showed increased mRNA expression of sPLA2-IIA (Li et al., 1999; Wang and Sun, 2000; Jensen et al., 2009). In this study, we first determined whether stimulation of DITNC astrocytes with TNFα and IL-1β induced sPLA2-IIA secretion. Western blot analysis showed that no sPLA2-IIA was detected in the culture medium of non-stimulated (control) cells whereas cytokines stimulated DITNC astrocytes to secret sPLA2-IIA into the conditioned medium (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Cytokine induced sPLA2-IIA secretion in DITNC cells. DITNC cells were exposed to cytokines (TNFα and IL-1β, 10 ng/ml) for 8 h, followed by removing cytokines and incubating in serum-free medium for another 40 h. Conditioned medium was used for Western blot analysis of sPLA2-IIA. Data are expressed as percentages of control and mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (***p < 0.001).

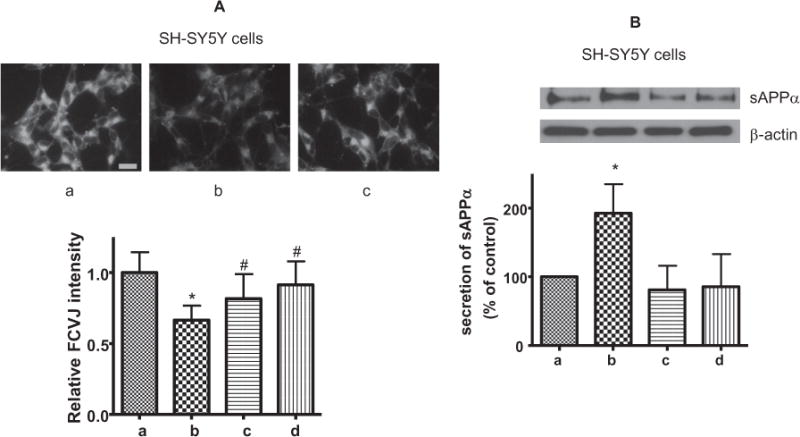

Conditioned medium from cytokine-stimulated DITNC astrocytes increased membrane fluidity and sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells

Since PLA2s have been shown to increase sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells (Cho et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2010), it is reasonable to hypothesize a role for sPLA2-IIA on mediating increase in sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells. To test this hypothesis, we applied the conditioned medium from control and cytokine-stimulated DITNC cells to SH-SY5Y cells. As indicated by a lower FCVJ intensity, the conditioned medium containing sPLA2-IIA from cytokine-stimulated DITNC astrocytes caused an increase in membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 2A). The conditioned medium also promoted sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, there is a significant reduction of membrane fluidity and sAPPα secretion when a selective inhibitor for sPLA2-IIA, KH064, is introduced to the stimulated and non-stimulated conditioned media (Fig. 2). sPLA2-IIA inhibitor alone did not cause any effects on membrane fluidity and sAPPα secretion (Fig. 2). The results indicate that sPLA2-IIA from stimulated DITNC cells plays an important role in SH-SY5Y cell membrane fluidity and sAPPα secretion.

Fig. 2.

SH-SY5Y cells were treated with conditioned medium containing sPLA2-IIA from cytokine-stimulated DITNC cells. (a): The conditioned medium from non-stimulated DITNC cells (control). (b): The conditioned medium from cytokine-stimulated DITNC cells. (c): The conditioned medium from cytokine-stimulated DITNC cells supplemented with the sPLA2-IIA inhibitor (KH064, 1 μM). (d): The conditioned medium from non-stimulated DITNC cells supplemented with KH064. (A, upper) Representative images of SH-SY5Y cells fluorescently labeled with FCVJ with conditioned medium treatment. (Scale bar=20 μm) (A, lower) The relative fluorescent intensity of FCVJ where a lower intensity indicates increased membrane fluidity. (B) Western blot analysis of sAPPα secretion with SH-SY5Y cells treated with the aforementioned DITNC conditioned media treatment groups. Data are expressed as percentages of control and mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments with statistical analysis performed with a one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc tests (*p < 0.05 when compared to the control group (a) and #p < 0.05 when compared to the conditioned media treatment group (b)).

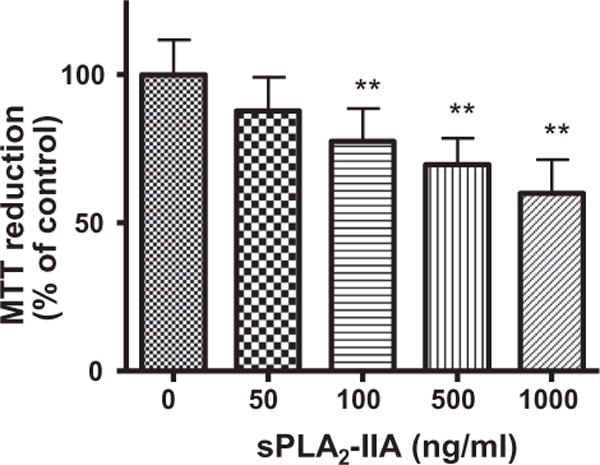

Exogenous sPLA2-IIA increased membrane fluidity and sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells

To further test the ability for sPLA2-IIA to alter membrane fluidity and sAPPα secretion, we investigated the effects of recombinant human sPLA2-IIA. First, we examined the viability of SH-SY5Y cells in response to different doses of sPLA2-IIA using the MTT test. Results in Fig. 3 show a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability upon exposing SH-SY5Y cells to sPLA2-IIA for 24 h. The results show that there is no significant decrease in cell viability with a 50 ng/ml dose while a 100 ng/ml dose will yield ~75% SH-SY5Y cell viability. All of the subsequent experiments were performed with both 50 and 100 ng/ml sPLA2-IIA concentrations to assess how sPLA2-IIA affects SH-SY5Y cells.

Fig. 3.

Effects of human recombined sPLA2-IIA on the viability of SH-SY5Y cells. MTT assay was applied after treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with different levels of sPLA2-IIA. Data are expressed as percentages of control and mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (**p < 0.01).

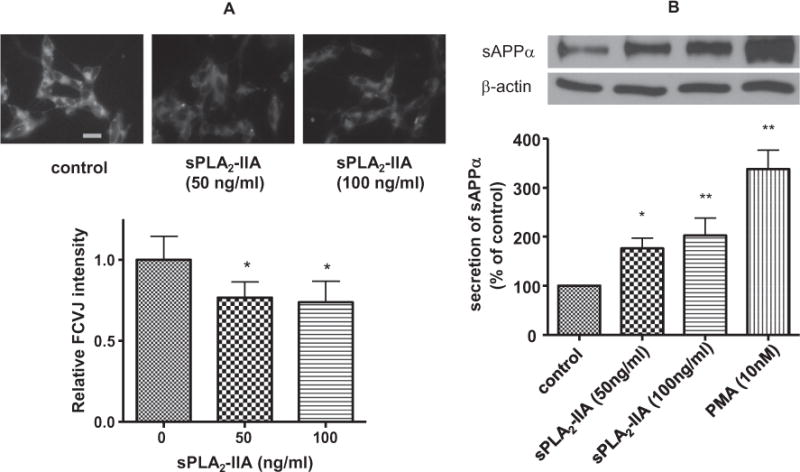

The recombinant human sPLA2-IIA was also used to test membrane fluidity. As shown in Fig. 4A, SH-SY5Y cells exhibited a lower fluorescent intensity of FCVJ after treatment with sPLA2-IIA, as compared with control, suggesting that sPLA2-IIA action can increase membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells. Together, these data suggest that sPLA2-IIA increased sAPPα through its action to increase membrane fluidity. Western blot analysis showed that sPLA2-IIA (50 and 100 ng/ml) increased sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 4B). Since PMA, a PKC agonist, has been reported to increases sAPPα secretion (Caporaso et al., 1992; Slack et al., 1993; Camden et al., 2005), SH-SY5Y cells were treated with PMA (10 nM) as a positive control.

Fig. 4.

(A) Effects of human recombined sPLA2-IIA on SH-SY5Y cell membrane fluidity. Representative images of SH-SY5Y cells fluorescently labeled with FCVJ without (upper, left) and with sPLA2-IIA treatment (upper, middle and right). Scale bar=20 μm. (B) Effects of human recombined sPLA2-IIA on sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells. After treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with sPLA2-IIA, the culture medium was used for Western blot analysis of sAPPα. Results showed that sPLA2-IIA increased sAPPα secretion to medium from SH-SY5Y cells. PMA treatment known to increase sAPPα secretion in cells was used as a positive control. Data are expressed as percentages of control and mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

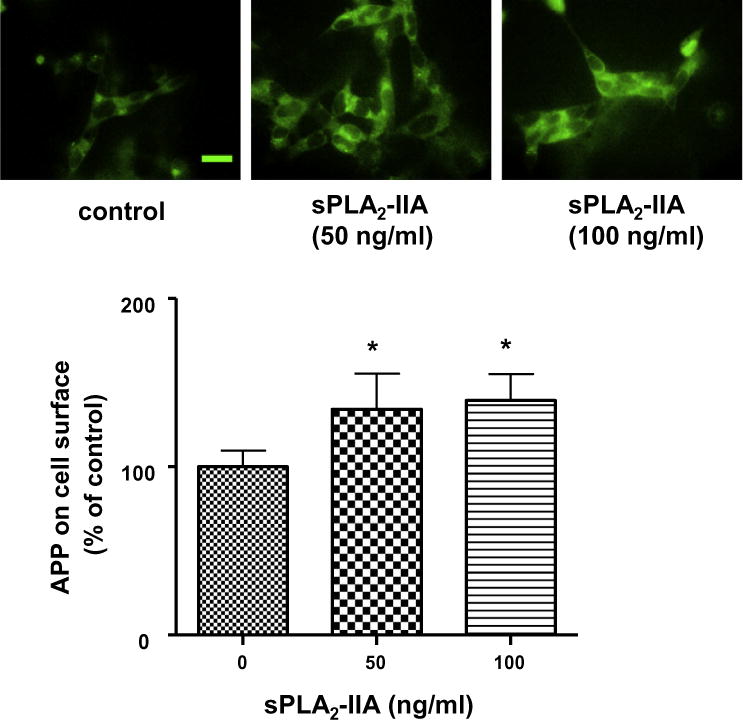

Exogenous sPLA2-IIA increased APP at the cell surface of SH-SY5Y cells

There is substantial evidence suggesting that the amyloidogenic pathway to generate Aβ occurs preferentially in the intracellular compartments, whereas the non-amyloidogenic pathway for production of sAPPα preferentially occurs at the plasma membranes (Haass et al., 1993; Koo and Squazzo, 1994; Kinoshita et al., 2003; Small and Gandy, 2006; Cirrito et al., 2008; Rajendran et al., 2008; Schobel et al., 2008; von Arnim et al., 2008). Based on these studies, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the increase of membrane fluidity by sPLA2-IIA favors the non-amyloidogenic pathway by lowering APP internalization and thus leading to an increase of APP at the cell surface of SH-SY5Y cells. To test this hypothesis, we fluorescently labeled the extracellular domain of APP without membrane permeabilization. Immunofluorescence microscopy showed that sPLA2-IIA enhanced the labeling of APP at the cell surface (Fig. 5). Quantification of the fluorescent intensity indicated sPLA2-IIA increased APP at the cell surface by ~40%.

Fig. 5.

Immunofluorescence microscopy showing effects of sPLA2-IIA on the presence of APP at the cell surface of SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with human recombined sPLA2-IIA for 24 h and were labeled with anti-APP antibody and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody without cell permeabilization. Representative images of fluorescently labeled SH-SY5Y cells without (upper, left) and with sPLA2-IIA treatment (upper, middle and right) showed sPLA2-IIA increased the APP accumulation at the cell surface (lower). Scale bar=20 μm. sPLA2-IIA increased the APP accumulation at the cell surface (lower). Data are expressed as percentages of control and mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p < 0.05).

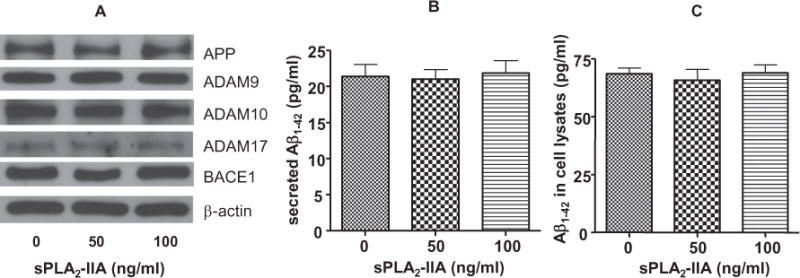

Exogenous sPLA2-IIA did not alter levels of total APP and α-secretase expression in SH-SY5Y cells

In order to rule out the changes in total APP and α-secretase expression being factors to enhance the release of sAPPα, Western blot analysis was carried out after exposing SH-SY5Y cells to sPLA2-IIA for 24 h. Results showed that sPLA2-IIA did not alter the expressions of APP and different isoforms of α-secretases including ADAM9, ADAM10 and ADAM17 (Fig. 6A). These results showed that expressions of APP and α-secretases were not factors in the increased sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells when exposed to sPLA2-IIA.

Fig. 6.

(A) sPLA2-IIA on the expressions of APP, α-secretases and BACE1 in SH-SY5Y cells. Western blot analysis showed that sPLA2-IIA did not alter the expressions of APP, different isoforms of α-secretases (ADAM 9, ADAM 10 and ADAM 17) and BACE1. (B) ELISA assay to quantify Aβ1–42 production from SH-SY5Y cells treated with 0, 50 or 100 ng/ml of sPLA2-IIA. sPLA2-IIA did not alter Aβ1–42 secretion from SH-SY5Y cells to culture medium. (C) sPLA2-IIA did not alter the expression of Aβ1–42 within SH-SY5Y cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Exogenous sPLA2-IIA did not alter levels of Aβ1–42 in SH-SY5Y cells

Since sPLA2-IIA increased the secretion of sAPPα in SH-SY5Y cells, it is possible that this activity may decrease the production and secretion of Aβ1–42 in these cells. However ELISA measurements showed that the secretion and production of Aβ1–42 from SH-SY5Y cells was not altered upon treatment with sPLA2-IIA for 24 h (Fig. 6B, C). Furthermore, Western blot analysis showed that exposing SH-SY5Y cells to sPLA2-IIA for 24 h did not alter the expressions of BACE1 (Fig. 6A).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provided evidence showing the ability for pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNFα and IL-1β) to induce sPLA2-IIA production and release to culture medium in DITNC astrocytes. We also showed the action of sPLA2-IIA to alter membrane fluidity and enhance sAPPα secretion from neuron cells (SH-SY5Y). Studies further demonstrated that action of sPLA2-IIA was abrogated through blocking by specific inhibitor and that exogenous human recombinant sPLA2-IIA added to neuron cells also produced similar results.

Astrocytes regulate neuronal activities in a variety of ways under physiological and pathological conditions. They are providers of nutrients and recycling units for neurotransmitters. In many pathological conditions, astrocytes become reactive and some genes are upregulated, which is associated with increase in immune responses and alteration of signaling pathways leading to release of cytokines and altered response to oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways (Zamanian et al., 2012). Metabolic interactions between reactive astrocytes and neuronal cells under pathological conditions have been an important subject for investigation.sPLA2-IIA is regarded an inflammatory enzyme and increased levels in plasma have been well demonstrated in human inflammatory diseases such as arthritis (Hurt-Camejo et al., 2001). There is also recognition about the role of sPLA2-IIA in neurological disorders (Yagami et al., 2014). In our earlier studies, an increase in sPLA2-IIA was observed in astrocytes in AD brain as compared with non-demented elderly brains (Moses et al., 2006). Increase in sPLA2-IIA mRNA was also observed in the rat brain after focal cerebral ischemia (Lin et al., 2004). In studies with astrocytes, pro-inflammation cytokines were shown to increase sPLA2-IIA mRNA expression through activation of the NF-jB transcription pathway (Li et al., 1999; Wang and Sun, 2000; Jensen et al., 2009). sPLA2-IIA from astrocytes was linked to the production of reactive oxygen species and apoptosis through activation of the superoxide producing enzyme NADPH oxidase in neurons (Yagami et al., 2014).

Although PLA2 are responsible for maintenance of phospholipid homeostasis and membrane properties, little is known about target action of sPLA2-IIA. In our previous study, sPLA2-III from bee venom was shown to alter membrane fluidity and increase sAPPα production in SH-SY5Y cells (Yang et al., 2010). In this study, we demonstrated that sPLA2-IIA from cytokine stimulated astrocytes regulates sAPPα secretion in neuronal cells. Our data in DITNC astrocytes showed that sPLA2-IIA is induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNFα and IL-1β, and is secreted to the culture medium (Fig. 1). By applying the conditioned medium to SH-SY5Y cells, we mimicked the effects of astrocyte–neuron interaction in brain. The conditioned medium containing sPLA2-IIA from cytokine-stimulated DITNC astrocytes increased sAPPα secretion and membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 2). Addition of selective sPLA2-IIA inhibitor to the conditioned medium abrogated the effects on sAPPα secretion and altered membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells, suggesting that active sPLA2-IIA is in part responsible for these effects (Fig. 2).

Our results showed that recombinant human sPLA2-IIA also increased sAPPα secretion and membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 4). These results are in agreement with other studies showing action of PLA2s to increase membrane fluidity (Kameyama et al., 1982; Schaeffer et al., 2005) and sAPPα secretion (Cho et al., 2006).

APP is a trans-membrane protein with cleavage sites for β- and γ-secretases to produce Aβ and for α-secretases to produce sAPPα (Small and Gandy, 2006; Muller and Zheng, 2012; Jiang et al., 2014; Perneczky et al., 2014). APP internalization and translocation to endosomes is a key factor for Aβ production (Kinoshita et al., 2003; Small and Gandy, 2006; Cirrito et al., 2008; Rajendran et al., 2008; Schobel et al., 2008; von Arnim et al., 2008). Kojro and colleagues (2001) have demonstrated increasing cholesterol content in cell membrane to decrease APP internalization and increase sAPPα secretion. This study also suggests that sPLA2-IIA decreases APP internalization (Fig. 5) and increases sAPPα secretion (Fig. 4). There is evidence that endogenous Aβ may decrease membrane fluidity and stimulate its own production, thus forming a vicious cycle (Peters et al., 2009). However, our data as well as those from Kojro et al. (2001) and Peters et al., 2009 tend to support the notion that high membrane fluidity leads to an increase in APP accumulation at the cell surface, and a subsequent increase in sAPPα production.

α-Secretase cleavage of APP has been reported to compete and preclude the β-secretases (BACE) cleavage, the primary step for production of harmful Aβ (Haass et al., 1993; Koo and Squazzo, 1994). However, in this study, enhanced sAPPα secretion (~ twofold) induced by sPLA2-IIA did not result in a detectable decrease in Aβ secretion and production (Fig. 6). In fact, Kim et al. (2008) was not able to show a link between sAPPα and Aβ production (Kim et al., 2008). Similarly, other studies have found that increased APP at the cell surface and sAPPα production do not necessarily result in an Aβ1–42 decrease when SH-SY5Y cells were treated with arachidonic acid (Yang et al., 2010, 2011). Certainly, further studies are needed to better understand underlying mechanism.

In agreement with the notion that AD is a chronic inflammatory disease, a number of studies indicated increased pro-inflammatory cytokines associated with the pathogenesis of this disease (Beloosesky et al., 2002; Lahiri et al., 2003; Cacquevel et al., 2004; Patel et al., 2005; Zuliani et al., 2007; Baranowska-Bik et al., 2008; Deniz-Naranjo et al., 2008; Couturier et al., 2010; Pellicano et al., 2010). For example, Aβ promotes the expression of TNFα and IL-1β in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from AD patients (Pellicano et al., 2010). Add discussion and citations about toxic Aβ to cells. In AD transgenic mouse models, inflammatory cytokine levels correlate positively with Aβ levels and locations (Mehlhorn et al., 2000; Apelt and Schliebs, 2001; Patel et al., 2005). Our study showed the induction of sPLA2-IIA from astrocytic DITNC cells by TNFα and IL-1β, and its role in APP processing. The roles of other metabolic components from cytokine-stimulated astrocytic cells in AD require more investigations to obtain more comprehensive understanding of astrocytes in regulation of neuronal activities.

In summary, our results showed that cytokine-stimulated DITNC cells, through sPLA2-IIA secretion, enhanced sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells by increasing membrane fluidity. This study should provide insights into not only the roles of sPLA2-IIA, but astrocytes in the regulation of APP processing in neurons.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH 1 R21 NS052385 (JCL), 5 R21 AG032579 (JCL), 1 R01 AG044404 (JCL), and P01 AG018357 (GS).

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- Aβ

amyloid-β peptide

- BACE1

β-site APP cleaving enzyme

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FCVJ

Farnesyl-(2-carboxy-2-cyanovinyl)-julolidine

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PLA2s

Phospholipases A2

- PMA

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- RA

all-trans retinoic acid

- sAPPα

α-secretase-cleaved soluble amyloid precursor protein

- sPLA2-IIA

group IIA secretory phospholipase A2

- sPLA2-III

group III secretory phospholipase A2

- TBST

Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Allinson TM, Parkin ET, Turner AJ, Hooper NM. ADAMs family members as amyloid precursor protein alpha-secretases. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:342–352. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apelt J, Schliebs R. Beta-amyloid-induced glial expression of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in cerebral cortex of aged transgenic Tg2576 mice with Alzheimer plaque pathology. Brain Res. 2001;894:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowska-Bik A, Bik W, Wolinska-Witort E, Martynska L, Chmielowska M, Barcikowska M, Baranowska B. Plasma beta amyloid and cytokine profile in women with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2008;29:75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beloosesky Y, Salman H, Bergman M, Bessler H, Djaldetti M. Cytokine levels and phagocytic activity in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Gerontology. 2002;48:128–132. doi: 10.1159/000052830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacquevel M, Lebeurrier N, Cheenne S, Vivien D. Cytokines in neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2004;5:529–534. doi: 10.2174/1389450043345308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camden JM, Schrader AM, Camden RE, Gonzalez FA, Erb L, Seye CI, Weisman GA. P2Y2 nucleotide receptors enhance alpha-secretase-dependent amyloid precursor protein processing. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18696–18702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso GL, Gandy SE, Buxbaum JD, Ramabhadran TV, Greengard P. Protein phosphorylation regulates secretion of Alzheimer beta/A4 amyloid precursor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:3055–3059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HW, Kim JH, Choi S, Kim HJ. Phospholipase A2 is involved in muscarinic receptor-mediated sAPPalpha release independently of cyclooxygenase or lypoxygenase activity in SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci Lett. 2006;397:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, Kang JE, Lee J, Stewart FR, Verges DK, Silverio LM, Bu G, Mennerick S, Holtzman DM. Endocytosis is required for synaptic activity-dependent release of amyloid-beta in vivo. Neuron. 2008;58:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier J, Page G, Morel M, Gontier C, Lecron JC, Pontcharraud R, Fauconneau B, Paccalin M. Inhibition of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase strongly decreases cytokine production and release in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21(4):1217–1231. doi: 10.3233/jad-2010-100258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deniz-Naranjo MC, Munoz-Fernandez C, Alemany-Rodriguez MJ, Perez-Vieitez MC, Aladro-Benito Y, Irurita-Latasa J, Sanchez-Garcia F. Cytokine IL-1 beta but not IL-1 alpha promoter polymorphism is associated with Alzheimer disease in a population from the Canary Islands, Spain. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:1080–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esch FS, Keim PS, Beattie EC, Blacher RW, Culwell AR, Oltersdorf T, McClure D, Ward PJ. Cleavage of amyloid beta peptide during constitutive processing of its precursor. Science. 1990;248:1122–1124. doi: 10.1126/science.2111583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory LS, Kelly WL, Reid RC, Fairlie DP, Forwood MR. Inhibitors of cyclo-oxygenase-2 and secretory phospholipase A2 preserve bone architecture following ovariectomy in adult rats. Bone. 2006;39:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C, Hung AY, Schlossmacher MG, Teplow DB, Selkoe DJ. Beta-Amyloid peptide and a 3-kDa fragment are derived by distinct cellular mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3021–3024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidekker MA, Ling T, Anglo M, Stevens HY, Frangos JA, Theodorakis EA. New fluorescent probes for the measurement of cell membrane viscosity. Chem Biol. 2001;8:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)90061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwig SS, Tan L, Qu XD, Cho Y, Eisenhauer PB, Lehrer RI. Bactericidal properties of murine intestinal phospholipase A2. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:603–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI117704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt-Camejo E, Paredes S, Masana L, Camejo G, Sartipy P, Rosengren B, Pedreno J, Vallve JC, Benito P, Wiklund O. Elevated levels of small, low-density lipoprotein with high affinity for arterial matrix components in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: possible contribution of phospholipase A2 to this atherogenic profile. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2761–2767. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2761::aid-art463>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MD, Sheng W, Simonyi A, Johnson GS, Sun AY, Sun GY. Involvement of oxidative pathways in cytokine-induced secretory phospholipase A2-IIA in astrocytes. Neurochem Int. 2009;55:362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia JP, Meng R, Sun YX, Sun WJ, Ji XM, Jia LF. Cerebrospinal fluid tau, Abeta1-42 and inflammatory cytokines in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Neurosci Lett. 2005;383:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Li Y, Zhang X, Bu G, Xu H, Zhang YW. Trafficking regulation of proteins in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:6. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama Y, Kudo S, Ohki K, Nozawa Y. Differential inhibitory effects by phospholipase A2 on guanylate and adenylate cyclases of Tetrahymena plasma membranes. Jpn J Exp Med. 1982;52:183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ML, Zhang B, Mills IP, Milla ME, Brunden KR, Lee VM. Effects of TNFalpha-converting enzyme inhibition on amyloid beta production and APP processing in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12052–12061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2913-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita A, Fukumoto H, Shah T, Whelan CM, Irizarry MC, Hyman BT. Demonstration by FRET of BACE interaction with the amyloid precursor protein at the cell surface and in early endosomes. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3339–3346. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojro E, Gimpl G, Lammich S, Marz W, Fahrenholz F. Low cholesterol stimulates the nonamyloidogenic pathway by its effect on the alpha -secretase ADAM 10. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5815–5820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081612998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo EH, Squazzo SL. Evidence that production and release of amyloid beta-protein involves the endocytic pathway. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17386–17389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri DK, Chen D, Vivien D, Ge YW, Greig NH, Rogers JT. Role of cytokines in the gene expression of amyloid beta-protein precursor: identification of a 5′-UTR-binding nuclear factor and its implications in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:81–90. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Xia J, Sun GY. Cytokine induction of iNOS and sPLA2 in immortalized astrocytes (DITNC): response to genistein and pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1999;19:121–127. doi: 10.1089/107999099314261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TN, Wang Q, Simonyi A, Chen JJ, Cheung WM, He YY, Xu J, Sun AY, Hsu CY, Sun GY. Induction of secretory phospholipase A2 in reactive astrocytes in response to transient focal cerebral ischemia in the rat brain. J Neurochem. 2004;90:637–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlhorn G, Hollborn M, Schliebs R. Induction of cytokines in glial cells surrounding cortical beta-amyloid plaques in transgenic Tg2576 mice with Alzheimer pathology. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000;18:423–431. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(00)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morioka N, Takeda K, Kumagai K, Hanada T, Ikoma K, Hide I, Inoue A, Nakata Y. Interleukin-1beta-induced substance P release from rat cultured primary afferent neurons driven by two phospholipase A2 enzymes: secretory type IIA and cytosolic type IV. J Neurochem. 2002;80:989–997. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses GS, Jensen MD, Lue LF, Walker DG, Sun AY, Simonyi A, Sun GY. Secretory PLA2-IIA: a new inflammatory factor for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2006;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller UC, Zheng H. Physiological functions of APP family proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006288. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard M, Ransom B, Goldman SA. New roles for astrocytes: redefining the functional architecture of the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessen HWM, Krijnen PAJ, Visser CA, Meijer CJLM, Erik Hack C. Type II secretory phospholipase A2 in cardiovascular disease: a mediator in atherosclerosis and ischemic damage to cardiomyocytes? Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60(1):68–77. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nipper ME, Majd S, Mayer M, Lee JC, Theodorakis EA, Haidekker MA. Characterization of changes in the viscosity of lipid membranes with the molecular rotor FCVJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1148–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NS, Paris D, Mathura V, Quadros AN, Crawford FC, Mullan MJ. Inflammatory cytokine levels correlate with amyloid load in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicano M, Bulati M, Buffa S, Barbagallo M, Di Prima A, Misiano G, Picone P, Di Carlo M, Nuzzo D, Candore G, Vasto S, Lio D, Caruso C, Colonna-Romano G. Systemic immune responses in Alzheimer’s disease: in vitro mononuclear cell activation and cytokine production. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21:181–192. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira A, Jr, Furlan FA. Astrocytes and human cognition: modeling information integration and modulation of neuronal activity. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92:405–420. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perneczky R, Alexopoulos P, Kurz A. Soluble amyloid precursor proteins and secretases as Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters I, Igbavboa U, Schutt T, Haidari S, Hartig U, Rosello X, Bottner S, Copanaki E, Deller T, Kogel D, Wood WG, Muller WE, Eckert GP. The interaction of beta-amyloid protein with cellular membranes stimulates its own production. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:964–972. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran L, Schneider A, Schlechtingen G, Weidlich S, Ries J, Braxmeier T, Schwille P, Schulz JB, Schroeder C, Simons M, Jennings G, Knolker H-J, Simons K. Efficient inhibition of the Alzheimer’s disease {beta}-secretase by membrane targeting. Science. 2008;320:520–523. doi: 10.1126/science.1156609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer EL, Bassi F, Jr, Gattaz WF. Inhibition of phospholipase A2 activity reduces membrane fluidity in rat hippocampus. J Neural Transm. 2005;112:641–647. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schobel S, Neumann S, Hertweck M, Dislich B, Kuhn PH, Kremmer E, Seed B, Baumeister R, Haass C, Lichtenthaler SF. A novel sorting nexin modulates endocytic trafficking and alpha-secretase cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14257–14268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack BE, Nitsch RM, Livneh E, Kunz GM, Jr, Eldar H, Wurtman RJ. Regulation of amyloid precursor protein release by protein kinase C in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;695:128–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb23040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Gandy S. Sorting through the cell biology of Alzheimer’s disease: intracellular pathways to pathogenesis. Neuron. 2006;52:15–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun GY, Horrocks LA, Farooqui AA. The roles of NADPH oxidase and phospholipases A2 in oxidative and inflammatory responses in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem. 2007;103:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun GY, Xu J, Jensen MD, Simonyi A. Phospholipase A2 in the central nervous system: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:205–213. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R300016-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton E, Vink R, Blumbergs PC, Van Den Heuvel C. Soluble amyloid precursor protein alpha reduces neuronal injury and improves functional outcome following diffuse traumatic brain injury in rats. Brain Res. 2006;1094:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touqui L, Alaoui-El-Azher M. Mammalian secreted phospholipases A2 and their pathophysiological significance in inflammatory diseases. Curr Mol Med. 2001;1:739–754. doi: 10.2174/1566524013363258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R. BACE1: the beta-secretase enzyme in Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;23:105–114. doi: 10.1385/JMN:23:1-2:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Arnim CA, von Einem B, Weber P, Wagner M, Schwanzar D, Spoelgen R, Strauss WL, Schneckenburger H. Impact of cholesterol level upon APP and BACE proximity and APP cleavage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JH, Sun GY. Platelet activating factor (PAF) antagonists on cytokine induction of iNOS and sPLA2 in immortalized astrocytes (DITNC) Neurochem Res. 2000;25:613–619. doi: 10.1023/a:1007550801444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinrauch Y, Elsbach P, Madsen LM, Foreman A, Weiss J. The potent anti-Staphylococcus aureus activity of a sterile rabbit inflammatory fluid is due to a 14-kD phospholipase A2. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:250–257. doi: 10.1172/JCI118399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagami T, Ueda K, Asakura K, Nakazato H, Hata S, Kuroda T, Sakaeda T, Sakaguchi G, Itoh N, Hashimoto Y, Hori Y. Human group IIA secretory phospholipase A2 potentiates Ca2+ influx through L-type voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels in cultured rat cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 2003;85:749–758. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagami T, Yamamoto Y, Koma H. The role of secretory phospholipase A2 in the central nervous system and neurological diseases. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:863–876. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8565-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Sheng W, Haidekker M, Sun G, Lee J. Secretory phospholipase A2 Type III enhances α-secretase-dependent amyloid precursor protein processing by its effect on membrane fluidity and endocytosis. Biophys J. 2009;96:100a. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Sheng W, He Y, Cui J, Haidekker MA, Sun GY, Lee JC. Secretory phospholipase A2 type III enhances alpha-secretase-dependent amyloid precursor protein processing through alterations in membrane fluidity. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:957–966. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Sheng W, Sun GY, Lee JCM. Effects of fatty acid unsaturation numbers on membrane fluidity and α-secretase-dependent amyloid precursor protein processing. Neurochem Int. 2011;58:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamanian JL, Xu L, Foo LC, Nouri N, Zhou L, Giffard RG, Barres BA. Genomic analysis of reactive astrogliosis. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6391–6410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6221-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuliani G, Ranzini M, Guerra G, Rossi L, Munari MR, Zurlo A, Volpato S, Atti AR, Ble A, Fellin R. Plasma cytokines profile in older subjects with late onset Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]