Abstract

Background

Renal osteodystrophy encompasses the bone histologic abnormalities seen in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (bALP) isoform B1x is exclusively found in serum of some CKD patients.

Study Design

The aim of this cross-sectional diagnostic test study was to examine the relationship between serum bALP isoform activities and histomorphometric parameters of bone in patients with CKD receiving long-term hemodialysis.

Settings & Participants

Anterior iliac crest bone biopsy samples from 40 CKD patients were selected on the basis of bone turnover for histomorphometric analysis. There were samples from 20 patients with low and 20 with non-low bone turnover.

Index Test

In serum, bALP, bALP isoforms (B/I, B1x, B1, and B2), and parathyroid hormone (PTH) were measured.

Reference Test

Low bone turnover was defined by mineral apposition rate < 0.36 µm per day. Non-low bone turnover was defined by mineral apposition rate ≥ 0.36 µm per day.

Other Measurements

PTH.

Results

B1x was found in 21 patients (53%) who had lower median levels of bALP, 18.6 versus 46.9 U/L; B/I, 0.10 versus 0.22 µkat/L; B1, 0.40 versus 0.88 µkat/L; B2, 1.21 versus 2.66 µkat/L; and PTH, 49 versus 287 pg/mL, compared to patients without B1x (p<0.001). Thirteen patients (65%) with low bone turnover and 8 patients (40%) with non-low bone turnover (p<0.2) had detectable B1x. B1x correlated inversely with histomorphometric parameters of bone turnover. Receiver operating characteristic curves showed that B1x can be used for diagnosis of low bone turnover (area under the curve [AUC], 0.83), while bALP (AUC, 0.89) and PTH (AUC, 0.85) are useful for diagnosis of non-low bone turnover.

Limitations

Small number of study participants. Requirement of high-performance liquid chromatography methods for measurement of B1x.

Conclusions

B1x, PTH and BALP have similar diagnostic accuracy in distinguishing low from non-low bone turnover. The presence of B1x is diagnostic of low bone turnover whereas elevated BALP and PTH are useful for diagnosis of non-low bone turnover.

Keywords: Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (bALP); bALP isoforms; B/I, B1x, B1, B2, renal osteodystrophy; bone histology; low bone turnover; mineral apposition rate; parathyroid hormone (PTH); hemodialysis, end-stage renal disease (ESRD); diagnostic test study

Renal osteodystrophy encompasses bone histologic abnormalities of chronic kidney disease (CKD)–mineral bone disorder, which consist of changes in bone turnover, mineralization and volume.1, 2 Bone turnover is customarily assessed by serum concentrations of parathyroid hormone (PTH) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP). The predictive value of PTH for bone turnover is, however, limited.3, 4 Circulating total ALP comprises six isoforms in serum from healthy people. Thanks to weak anion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), these ALP isoforms can be separated and quantified: one bone/intestinal (B/I), two bone (B1 and B2), and three liver (L1, L2, and L3).5 In addition, a novel bone isoform, B1x, was previously identified in serum from patients with moderate CKD and in patients with CKD stage 5 on dialysis (stage 5D).6, 7 It has been found in extracts of human bone tissue, but has never been identified in serum from healthy individuals or from other patient populations.8 Prior characterization studies with monoclonal antibodies, heat-inactivation and various inhibitors verify B1x being of bone origin.9 It has been detected in serum from a bilaterally nephrectomized patient as well, which discounts B1x potentially being a kidney ALP isoform.9 Nonetheless, the clinical significance and physiological role of B1x remains unclear. It has been suggested that the presence of circulating B1x is associated with low serum concentrations of markers of bone turnover.7, 8 The present study tests the hypothesis that B1x levels in serum are reflective of low bone turnover.

METHODS

Design

The present diagnostic test study was designed as a cross-sectional proof-of-concept experiment investigating the performance of various isoforms of bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (bALP) as diagnostic tests for the discrimination between low and non-low bone turnover in patients with CKD-5D. Specifically, bone histomorphometry was used as the reference test and presence or absence of B1x as the index test. A bone histomorphometry–determined mineral apposition rate < 0.36 µm per day was used as the cutoff value for diagnosis of low bone turnover; ≥ 0.36 µm per day, for diagnosis of non-low bone turnover. The only additional serum biochemical parameters measured were serum PTH, calcium and phosphorus.

Study Population

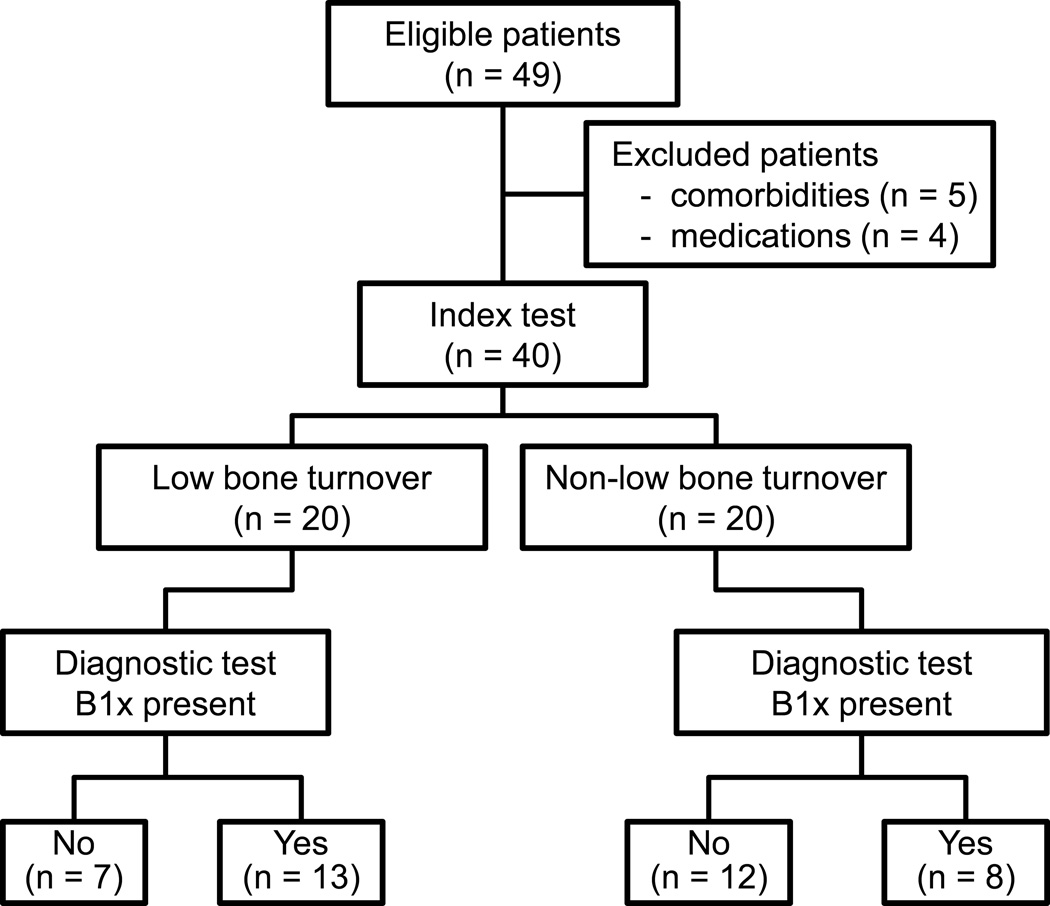

Bone biopsies and serum samples from patients with CKD-5D were selected sequentially from the Kentucky Renal Osteodystrophy Registry. All blood samples were drawn at time of bone biopsy, processed, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until the analysis for this study. Twenty patients with low bone turnover and 20 with non-low bone turnover were included in the study (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: age 18 years or older; dialysis vintage at least three months; and histomorphometric evidence of low or non-low bone turnover. Exclusion criteria included systemic illnesses or organ diseases that may affect bone (except diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2); chronic alcoholism and/or drug addiction; and treatment within the past six months with drugs that may affect bone metabolism (including bisphosphonate, selective estrogen receptor modulator, teriparatide, cinacalcet, and others except for vitamin D). The Kentucky Renal Osteodystrophy Registry is institutional review board approved and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Biochemical Analyses

Serum PTH levels were determined by the electrochemiluminescence Elecsys PTH assay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), with assay performance as follows: detection limit, 1.20 pg/mL; measuring upper limit, 5,000 pg/mL; intraassay coefficient of variation (CV), <4%; and interassay CV, <5%. The reference interval for healthy individuals is 18–74 pg/mL. Serum bALP levels were measured with the MicroVue BAP enzyme immunoassay (Quidel Corp., San Diego, CA). Assay performance for the MicroVue BAP assay was as follows: detection limit, 0.7 U/L; measuring upper limit, 140 U/L; intraassay CV, <6%; and interassay CV, <8%. The reference interval for healthy individuals is 11.6–42.7 U/L.

The bALP isoforms B/I, B1x, B1, and B2 were determined by a previously described HPLC method.5, 10 In brief, the bALP isoforms were separated using a gradient of 0.6 mol/L sodium acetate on a weak anion-exchange column, SynChropak AX300 (250 mm [length] × 4.6 mm [inner diameter]) (Eprogen, Inc., Darien, IL). The column effluent was mixed online with the substrate solution, 1.8 mmol/L p-nitrophenylphosphate in a 0.25 mol/L diethanolamine buffer at pH 10.1. The ensuing reaction was developed in a packed-bed post-column reactor at 37°C and the formed product (p-nitrophenol) was directed on-line through a detector set at 405 nm. The areas under each peak were integrated and the total ALP activity was used to calculate the relative activity of each of the detected bALP isoforms. The relationship between the enzyme activity units is that 1.0 µkat/L corresponds to 60 U/L. Assay performance for the bALP isoform HPLC method is as follows: for the B/I isoform: detection limit, 0.01 µkat/L; measuring upper limit, 1.70 µkat/L; B1x isoform: detection limit, 0.02 µkat/L; measuring upper limit, 1.00 µkat/L; B1 isoform: detection limit, 0.02 µkat/L; measuring upper limit, 4.70 µkat/L; and B2 isoform: detection limit, 0.03 µkat/L; measuring upper limit, 9.50 µkat/L. The intra- and interassay CVs were 5% and 6%, respectively, for each of the bALP isoforms.5 Samples with values above the assay range were diluted in appropriate assay diluent as necessary. The bALP isoform reference intervals for healthy individuals are as follows: B/I, 0.04–0.17 µkat/L; B1, 0.20–0.62 µkat/L; and B2, 0.34–1.69 µkat/L.

Bone Biopsy, Mineralized Bone Histology, and Bone Histomorphometry

Prior to biopsy, patients were given oral tetracycline hydrochloride, 500 mg twice daily, for two days followed by a 10-day tetracycline-free interval and another course of 300-mg demeclocycline twice daily for four days. Iliac crest bone biopsies were performed four days thereafter.

Bone samples were fixed in ethanol, dehydrated and embedded in methyl methacrylate as described previously.11 Serial sections of 4- and 7-µm thickness were cut with a heavy duty microtome (Model HM360, Microm, Walldorf, Germany). Sections were stained with the modified Masson-Goldner trichrome stain12 for determination of static parameters of bone structure, bone formation, and resorption. Aurin tricarboxylic acid and solochrome azurine stains were done for determination of aluminum deposition.13, 14 Unstained sections were prepared for phase-contrast and fluorescence light microscopy for measurements of wall thickness and dynamic parameters of bone formation and mineralization.

Bone histomorphometry was done using the Osteoplan II system (C. Zeiss, New York, NY).15, 16 All measured histomorphometric parameters comply with the recommendations of the nomenclature committee of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.17, 18 When only single labels were present in cancellous bone (patients with very low bone turnover), mineral apposition rate was assigned a value of 0.1 µm/d and the dynamic parameters were calculated based on this value. This approach is based on recommendations by Hauge et al.19 and the nomenclature committee of the Society.17

Statistics

Data are expressed as median and interquartile range. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. The Mann-Whitney test was used to test differences between groups of patients with low versus non-low bone turnover and patients with versus without detectable B1x in serum. Kendall’s tau-b rank correlation coefficients were used for calculation of nonparametric correlations. We evaluated the performance of B1x, PTH and bALP to diagnose low versus non-low bone turnover by calculating the area under the curve (AUC) from receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Study Population

The 40 selected patients included 20 with low bone turnover and 20 with non-low bone turnover (Figure 1). There were 21 men and 19 women. The primary kidney diseases were diabetic nephropathy (n = 7), hypertension (n = 6), polycystic kidney disease (n = 4), obstructive nephropathy (n = 3), glomerulonephritis (n = 2), amyloidosis (n = 1), and unknown (n = 17). Patients were hemodialyzed three times per week. Demographic, clinical, and biochemical characteristics of the patients with low or non-low bone turnover are given in Table 1. There were no differences in use of phosphate binders and vitamin D analogs. Serum PTH and bALP levels were significantly lower in patients with low than in those with nonlow bone turnover (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients receiving long-term hemodialysis with low or non-low bone turnover.

| Low (n = 20) |

Non-low (n = 20) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (M:F) | 11:9 | 10:10 | 0.5 |

| Age (y) | 62.1 (47.5–73.1) | 53.3 (39.1–67.6) | 0.4 |

| Dialysis vintage (mo) | 65.5 (25.8–83.3) | 50.0 (27.0–78.0) | 0.7 |

| Ca-containing phosphate binder | 20 | 18 | 0.3 |

| Vitamin D analogs | 1 | 3 | 0.6 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 9.3 (8.9–10.5) | 9.2 (8.5–9.7) | 0.2 |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dL) | 5.3 (4.2–6.2) | 5.9 (4.6–6.9) | 0.2 |

| Serum PTH (pg/mL) | 83 (25–196) | 270 (117–690) | 0.01 |

| Serum bALP (U/L) | 22.4 (13.9–31.8) | 47.7 (23.9–59.4) | 0.01 |

| Serum B/I (µkat/L) | 0.14 (0.04–0.53) | 0.14 (0.04–0.61) | 0.6 |

| Serum B1x (µkat/L) | 0.08 (0.00–0.45) | 0.00 (0.00–0.24) | 0.2 |

| No. of patients with detectable B1x Serum B1 (µkat/L) |

13 (65) 0.59 (0.18–2.19) |

8 (40) 0.79 (0.22–5.35) |

0.2 0.3 |

| Serum B2 (µkat/L) | 1.75 (0.49–6.83) | 2.09 (0.59–27.91) | 0.3 |

Note: Values for categorical variables are given as number or number (percentage); values for continuous variables are given as median [interquartile range]. Conversion factor for units: calcium in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.2495; phosphorus in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.3229

Abbreviations: bALP, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase; Ca, calcium; PTH, parathyroid hormone

Histomorphometric Analysis

In the patients with low bone turnover, half of the bone samples (n = 10) presented with single labels only and, for these patients, dynamic parameters were calculated based on the assigned value of mineral apposition rate of 0.1 µm/d (see Methods). No bone sample exhibited osteomalacia or positive aluminum staining. There were no differences in parameters of bone structure between the groups with low and non-low turnover. The number of osteoblasts and osteoclasts were lower in patients with low bone turnover. Also, dynamic parameters of bone formation were significantly lower in patients with low bone turnover (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bone histomorphometric parameters in patients receiving hemodialysis with low or non-low bone turnover.

| Low (n = 20) |

Non-low (n = 20) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters of bone structure | |||

| Bone volume/Tissue volume (%) | 20.0 (16.2–23.4) | 20.1 (15.5–25.1) | 0.9 |

| Trabecular thickness (µm) | 93.8 (77.0–116) | 96.9 (76.0–125) | 0.6 |

| Trabecular separation (µm) | 353 (298–469) | 356 (295–517) | 0.7 |

| Static parameters of bone formation | |||

| Osteoid volume/Bone volume (%) | 5.40 (3.25–16.1) | 9.64 (6.10–18.8) | 0.08 |

| Osteoid surface/Bone surface (%) | 28.2 (13.3–51.8) | 43.3 (27.9–53.5) | 0.08 |

| Osteoid thickness (µm) | 9.97 (8.07–14.4) | 12.2 (9.82–15.7) | 0.07 |

| No. of osteoblast/bone perimeter (no./100 mm) | 22.1 (10.1–48.7) | 201 (81.3–305) | < 0.001 |

| Parameters of bone resorption | |||

| Erosion surface/Bone surface (%) | 1.67 (0.59–2.94) | 2.29 (0.97–6.21) | 0.2 |

| Erosion depth (µm) | 12.2 (8.84–13.3) | 13.5 (10.6–18.2) | 0.4 |

| No. of osteoclast/bone perimeter (no./100 mm) | 14.6 (10.8–25.7) | 29.0 (12.5–89.1) | 0.04 |

| Dynamic parameters | |||

| Mineral apposition rate (µm/d) | 0.31 (0.10–0.78) | 0.89 (0.80–1.09) | < 0.001 |

| Mineralizing surface/Bone surface (%) | 2.22 (0.74–4.1) | 9.73 (6.66–14.9) | < 0.001 |

| Bone formation rate/Bone surface (mm3/cm2y) | 0.15 (0.03–1.06) | 3.15 (2.42–3.95) | < 0.001 |

| Activation frequency (y−1) | 0.03 (0.01–0.21) | 0.64 (0.57–0.78) | < 0.001 |

| Mineralization lag time (d) | 268 (141–1622) | 69.9 (38.8–104) | < 0.001 |

| Bone formation rate/osteoblast (mm3/cell/y × 103) | 4.79 (2.29–23.3) | 15.8 (10.0–23.7) | 0.04 |

| Osteoblast vigor (%/d) | 0.09 (0.02–0.23) | 0.51 (0.37–0.79) | < 0.001 |

Note: Values are given as median [interquartile range]

bALP Isoforms

The bALP isoforms B/I, B1 and B2 were detected in all patients. B1x was detected in 21 patients (53%); 13 and 8 of those were patients with low and non-low bone turnover, respectively. All patients with low bone turnover and only single labels in cancellous bone had detectable B1x serum levels. The bALP isoforms B/I, B1, and B2 correlated positively with each other, and with bALP and PTH. B1x, however, correlated negatively with B1, B2, bALP, and PTH, but not with B/I (Table 3).

Table 3.

Kendall’s tau-b rank correlation coefficients between serum markers and histomorphometric parameters of bone formation in patients receiving long-term hemodialysis

| N.Ob/B.Pm | Ob.Vg | BFR/BS | MAR | Mlt | MS/BS | B1x | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B/I | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.09 | −0.19 |

| B1x | −0.30a | −0.26a | −0.26a | −0.29a | 0.28a | −0.25a | - |

| B1 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.14 | −0.15 | 0.17 | −0.25a |

| B2 | 0.28a | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.16 | −0.18 | 0.20 | −0.23a |

| BALP | 0.43a | 0.38a | 0.39a | 0.36a | −0.37a | 0.38a | −0.35a |

| PTH | 0.40a | 0.39a | 0.37a | 0.33a | −0.35a | 0.37a | −0.32a |

bALP, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase; PTH, parathyroid hormone; N.Ob/B.Pm, number of osteoblasts per bone perimeter; Ob.Vg, osteoblast vigor; BFR/BS, bone formation rate per bone surface; MAR, mineral apposition rate; Mlt, mineralization lag time; MS/BS, mineralizing surface per bone surface.

Significant association (p<0.05)

Comparisons Between Patients With and Without Detectable B1x

Patients with measurable B1x had significantly lower serum levels of bALP, all other bALP isoforms, and PTH (Table 4). There were no differences in use of phosphate binders. All four patients who were treated with vitamin D had high bone turnover and no detectable B1x. Patients with detectable B1x showed significantly lower number of osteoblasts, mineral apposition rate, mineralizing surface, bone formation rate/bone surface, activation frequency, and osteoblastic activity at the cell level (osteoblast vigor). Accordingly, mineralization lag time was significantly longer in patients with detectable B1x (Table 5).

Table 4.

Demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients receiving long-term hemodialysis with absence or presence of circulating B1x.

| B1x Absent (n = 19) |

B1x Present (n = 21) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (M:F) | 8:11 | 13:8 | 0.2 |

| Age (y) | 48.7 (38.6–68.0) | 60.9 (52.1–69.5) | 0.09 |

| Dialysis vintage (mo) | 41.0 (24.8–75.8) | 68.0 (31.0–86.8) | 0.4 |

| Ca-containing phosphate binder | 18 | 20 | 0.9 |

| Vitamin D analogs | 4 | 0 | 0.04 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 9.20 (8.70–10.2) | 9.30 (8.98–10.1) | 0.8 |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dL) | 5.50 (4.80–6.10) | 5.60 (4.02–6.73) | 0.7 |

| Serum PTH (pg/mL) | 287 (124–898) | 49 (23–195) | <0.001 |

| Serum bALP (U/L) | 46.9 (31.8–82.6) | 18.6 (13.7–27.1) | <0.001 |

| Serum B/I (µkat/L) | 0.22 (0.14–0.27) | 0.10 (0.07–0.14) | <0.001 |

| Serum B1x (µkat/L) | 0 | 0.11 (0.04–0.45) | <0.001 |

| Serum B1 (µkat/L) | 0.88 (0.77–1.72) | 0.40 (0.26–0.63) | <0.001 |

| Serum B2 (µkat/L) | 2.66 (2.03–6.45) | 1.21 (0.69–2.00) | <0.001 |

Note: Values for categorical variables are given as number or number (percentage); values for continuous variables are given as median [interquartile range].Conversion factor for units: calcium in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.2495; phosphorus in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.3229.

Abbreviations: bALP, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase; Ca, calcium; PTH, parathyroid hormone

Table 5.

Bone histomorphometric parameters in patients receiving long-term hemodialysis with absence or presence of the circulating B1x

| B1x absent (n = 19) |

B1x present (n = 21) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters of bone structure | |||

| Bone volume/Tissue volume (%) | 20.1 (16.5–23.1) | 19.8 (15.8–24.7) | 0.9 |

| Trabecular thickness (µm) | 109 (74.7–120) | 93.9 (79.7–110) | 0.6 |

| Trabecular separation (µm) | 342 (295–546) | 375 (305–475) | 0.9 |

| Static parameters of bone formation | |||

| Osteoid volume/Bone volume (%) | 8.25 (5.20–20.8) | 6.44 (3.95–13.0) | 0.3 |

| Osteoid surface/Bone surface (%) | 43.8 (24.6–54.6) | 35.2 (15.7–46.5) | 0.3 |

| Osteoid thickness (µm) | 13.1 (9.79–15.1) | 10.2 (8.28–14.6) | 0.2 |

| No. of osteoblast/bone perimeter (no./100 mm) | 178 (61.5–349) | 33.5 (10.5–136) | <0.001 |

| Static parameters of bone resorption | |||

| Erosion surface/Bone surface (%) | 2.44 (1.56–6.15) | 0.98 (0.55–3.01) | 0.06 |

| Erosion depth (µm) | 13.0 (11.8–16.4) | 11.0 (9.04 –13.8) | 0.2 |

| No. of osteoclast/Bone perimeter (no./100 mm) | 23.8 (14.3–80.7) | 12.9 (10.8–30.7) | 0.07 |

| Dynamic parameters of bone formation and turnover | |||

| Mineral apposition rate (µm/d) | 0.83 (0.75–0.93) | 0.52 (0.10–0.88) | 0.02 |

| Mineralizing surface/Bone surface (%) | 6.52 (4.32–12.6) | 3.17 (0.80–8.7) | 0.02 |

| Bone formation rate/Bone surface (mm3/cm2/y) | 2.43 (1.57–3.86) | 0.55 (0.03–3.04) | 0.02 |

| Activation frequency (y−1) | 0.57 (0.33–0.65) | 0.16 (0.01–0.65) | 0.02 |

| Mineralization lag time (d) | 70.1 (46.1–136) | 225 (90.1–972) | 0.01 |

| Bone formation rate/osteoblast (mm3/cell/y×103) | 15.3 (5.07–38.5) | 9.97 (2.59–21.6) | 0.4 |

| Osteoblast vigor (%/d) | 0.49 (0.23–0.62) | 0.14 (0.02–0.37) | 0.02 |

Note: Values are given as median [interquartile range].

Relationships Between Biochemical and Histomorphometric Parameters

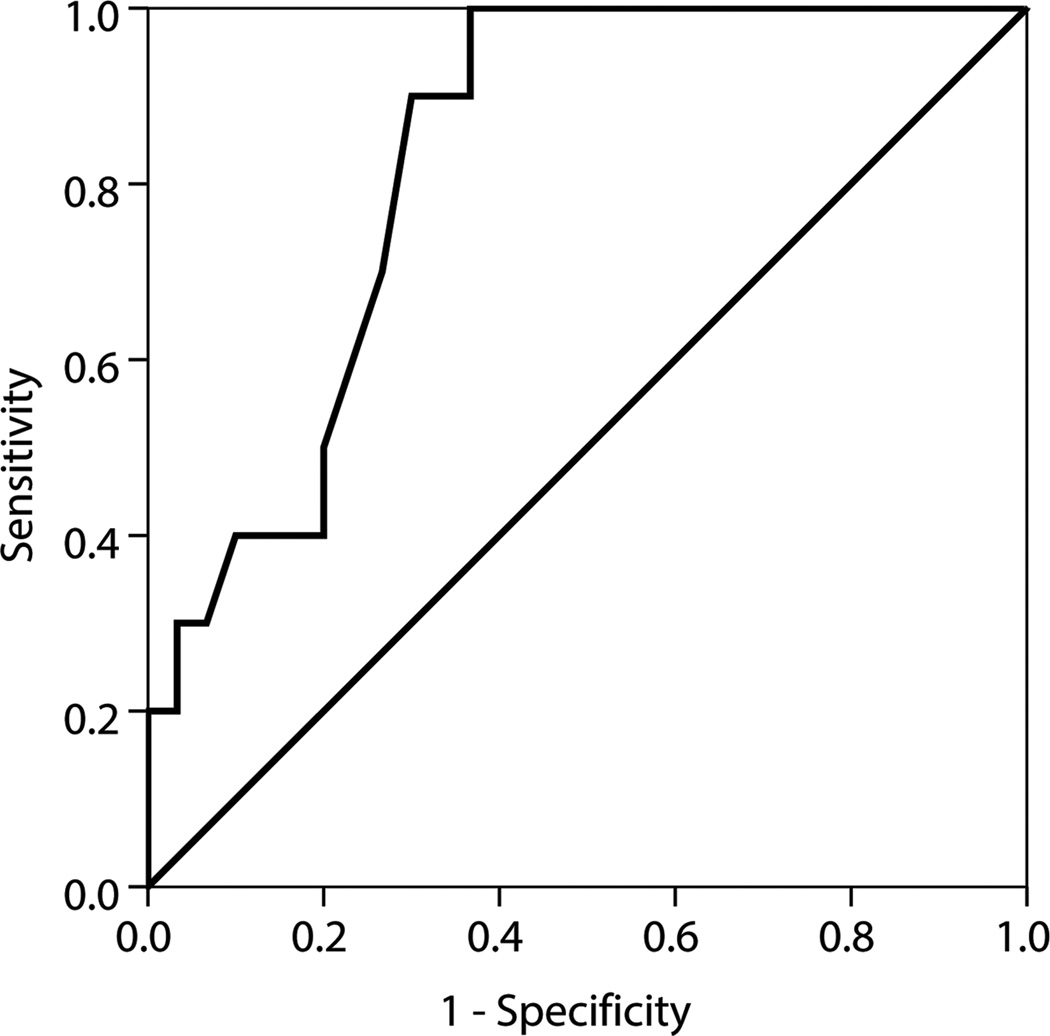

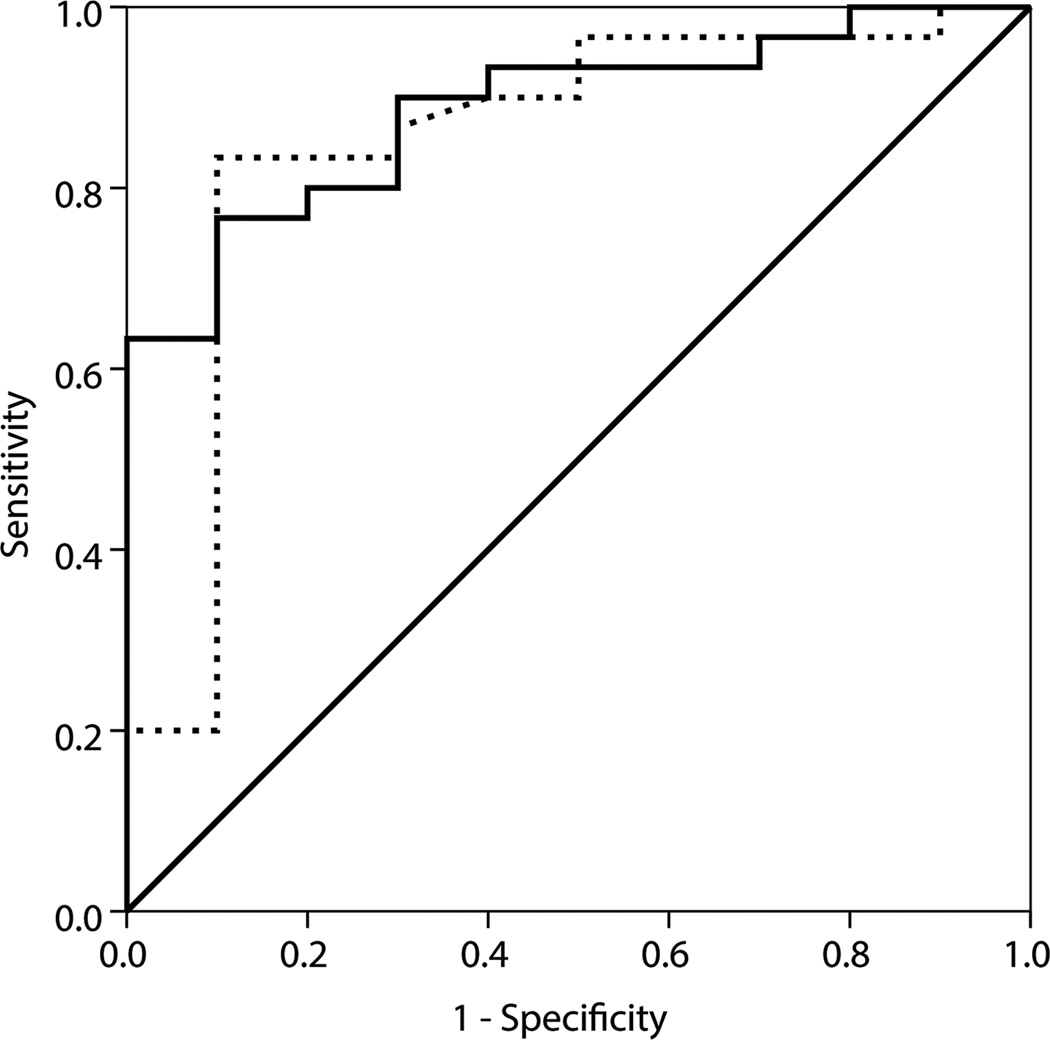

Whereas bALP and PTH correlated significantly with several parameters of bone turnover and mineralization, the bALP isoforms demonstrated a weaker relationship with these histomorphometric parameters (Table 3). The only biochemical parameter that inversely correlated with histomorphometric parameters of osteoblastic number and activity, indicating bone turnover, was B1x (Table 3). Figure 2 shows ROC curves of B1x, bALP and PTH for diagnosis of low (Figure 2a) and non-low (Figure 2b) bone turnover. The AUC of 0.83 for B1x shows that it is useful for diagnosis of low bone turnover, while AUCs of 0.89 and 0.85, respectively, for bALP and PTH show that these parameters are useful for diagnosis of nonlow bone turnover.

Figure 2.

ROC curves of (A) B1x for diagnosis of low bone turnover defined by mineral apposition rate < 0.36 µm/d and (B) bALP (—) and PTH (…) for diagnosis of non-low bone turnover defined by mineral apposition rate ≥ 0.36 µm/d.

DISCUSSION

In this study we describe, for the first time to our knowledge, the association of the bALP isoforms B/I, B1, B2, and B1x with results from histomorphometric analyses of iliac crest bone biopsies in patients with CKD-5d. The isoform B1x was detected in 53% of the patients. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies, which demonstrated the presence of B1x in 60% of unselected adult CKD-5d patients7 and 63% of CKD-5 patients not on dialysis.6

The main finding of the present study is the association of the bALP isoform B1x in serum with low bone turnover. The isoform B1x increased with lower bone turnover, while PTH, bALP and the other BALP isoforms (i.e., B/I, B1 and B2) increased with higher turnover. While the positive correlations of bALP and PTH with turnover have already been established in patients with CKD-5d,20, 21 the demonstration of the value of B1x for identification of low turnover is novel.

These findings may explain, at least in part, the rare presence of the bALP B1x isoform in children with CKD (7%).22 Longitudinal growth and pubertal status in children stimulate bone modeling/remodeling, and thus low bone turnover is rare in children.23, 24 Moreover, it has been shown that B1x was no longer detectable in serum of a CKD child treated with recombinant growth hormone,22 which is known to increase bone turnover.25

The isoform B1x is present in bone but is not released in detectable quantities into the circulation of healthy individuals.26 The detection of circulating B1x indicates a perturbed activity of osteoblasts in CKD-5d patients with mainly low bone turnover. The fact that B1x is not detected in some patients with low bone turnover may be explained by lower activity of B1x than either B/I and B1, which can coelute with B1x.9 The presence of B1x in serum of some individuals with non-low bone turnover might be the result of a transient phase when patients move from high to low bone turnover due to an emerging or incipient osteoblastic defect eventually resulting in low bone turnover. One can surmise that these patients are developing low bone turnover as frequently seen in patients with CKD-5d.11

The isoform B1x was inversely correlated with all other bALP isoforms in the current study. We have previously reported positive correlations of B1x with B/I and B1 in dialysis patients and, at the same time, significantly lower activities of both isoforms were found in patients with B1x.7 In predialysis patients with CKD stages 3–5, B1x was positively correlated with all bALP isoforms.6 In that study, differences in isoform activities between patients with and without B1x were not determined. A possible explanation for these discrepancies could be that the selection of patients according to bone turnover categories in the current study resulted in the inclusion of a disproportionately high number of patients with severely reduced bone turnover. This may be responsible for the high number of patients with labelling escape and the lower PTH levels in patients with B1x in the current study (i.e., 49 pg/mL vs. 183 pg/mL).7

In the current study, patients with detectable B1x in serum were somewhat older but the difference did not reach significance. To our knowledge, only one previous study has demonstrated an association of B1x in serum with older age.7 In predialysis patients we did not find an age-related difference between patients with or without B1x.6 The third report about B1x in serum from CKD patients was in a cohort aged 3–20 years (n=29) in which 2 patients had detectable B1x.22 The influence of age on B1x in serum was not investigated in that study. We have previously described an association of older age with low bone turnover.27 Thus, the appearance of B1x in serum is not strongly associated with older age, which is in accordance with the findings of the current study.

We used the MicroVue enzyme immunoassay for determination of bALP, which has a reported cross-reactivity with liver ALP in the range of 3%-15%. Monoclonal antibodies against bALP have been comprehensively discussed in an international workshop.28 Even though cross-reactivities with the liver ALP isoforms are well-known, and in spite of the lack of monoclonal antibodies that can distinguish between the bALP isoforms, the development of bALP immunoassays adapted for automated formats has led to an increased clinical use of serum bALP, particularly in the nephrology community.8 The HPLC assay used in the current study is the only method available for separation and quantification of the different bALP isoforms. General drawbacks for HPLC assays are, however, that they are time consuming and expensive in comparison with enzyme immunoassays. Development of easier methods for B1x measurement is in progress. Another limitation of the present study is the relatively small number of patients.

In conclusion, B1x, PTH and bALP have similar diagnostic accuracy in distinguishing low from non-low bone turnover. The presence of B1x is diagnostic of low bone turnover, whereas elevated bALP and PTH are useful for diagnosis of non-low bone turnover.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Cecilia Halling Linder and Guodong Wang for excellent technical assistance.

Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 080770. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was supported by grants from the Kentucky Nephrology Research Trust and the County Council of Östergötland, Sweden. The supporting institution did not have any input on the study design and interpretation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Contributions: Research idea and study design: MH, M-CM-F, PM, HHM; data acquisition: MH, M-CM-F, PM, HHM; data analysis/interpretation: MH, M-CM-F, PM, HHM; statistical analysis: MH, M-CM-F; supervision or mentorship: PM, HHM. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. HHM takes responsibility that this study has been reported honestly, accurately, and transparently; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1.Malluche HH, Monier-Faugere MC. Renal osteodystrophy: what's in a name? Presentation of a clinically useful new model to interpret bone histologic findings. Clin. Nephrol. 2006;65(4):235–242. doi: 10.5414/cnp65235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moe S, Drueke T, Cunningham J, et al. Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Kidney Int. 2006;69(11):1945–1953. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrett G, Sardiwal S, Lamb EJ, Goldsmith DJ. PTH--a particularly tricky hormone: why measure it at all in kidney patients? Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013;8(2):299–312. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09580911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herberth J, Monier-Faugere MC, Mawad HW, et al. The five most commonly used intact parathyroid hormone assays are useful for screening but not for diagnosing bone turnover abnormalities in CKD-5 patients. Clin. Nephrol. 2009;72(1):5–14. doi: 10.5414/cnp72005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnusson P, Lofman O, Larsson L. Determination of alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes in serum by high-performance liquid chromatography with post-column reaction detection. J. Chromatogr. 1992;576(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(92)80177-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haarhaus M, Fernstrom A, Magnusson M, Magnusson P. Clinical significance of bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms, including the novel B1x isoform, in mild to moderate chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009;24(11):3382–3389. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnusson P, Sharp CA, Magnusson M, Risteli J, Davie MW, Larsson L. Effect of chronic renal failure on bone turnover and bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms. Kidney Int. 2001;60(1):257–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sardiwal S, Magnusson P, Goldsmith DJ, Lamb EJ. Bone Alkaline Phosphatase in CKD-Mineral Bone Disorder. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2013;62(4):810–822. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.02.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magnusson P, Larsson L, Magnusson M, Davie MW, Sharp CA. Isoforms of bone alkaline phosphatase: characterization and origin in human trabecular and cortical bone. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1999;14(11):1926–1933. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.11.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magnusson P, Lofman O, Larsson L. Methodological aspects on separation and reaction conditions of bone and liver alkaline phosphatase isoform analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1993;211(1):156–163. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malluche HH, Faugere MC. Atlas of Mineralized Bone Histology. New York: Karger; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldner J. A modification of the Masson trichrome technique for routine laboratory purposes. Am J Pathol. 1938;14(2):237–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denton J, Freemont AJ, Ball J. Detection and distribution of aluminium in bone. J. Clin. Pathol. 1984;37(2):136–142. doi: 10.1136/jcp.37.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lillie PD, Fullmer HM. Histopathologic Technic and Practical Histochemistry. 4 ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malluche HH, Sherman D, Meyer W, Massry SG. A new semiautomatic method for quantitative static and dynamic bone histology. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1982;34(5):439–448. doi: 10.1007/BF02411282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manaka RC, Malluche HH. A program package for quantitative analysis of histologic structure and remodeling dynamics of bone. Comput. Programs Biomed. 1981;13(3–4):191–201. doi: 10.1016/0010-468x(81)90098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dempster DW, Compston JE, Drezner MK, et al. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013;28(1):2–17. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, et al. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols and units. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1987;2(6):595–610. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauge E, Mosekilde L, Melsen F. Missing observations in bone histomorphometry on osteoporosis: implications and suggestions for an approach. Bone. 1999;25(4):389–395. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monier-Faugere MC, Geng ZP, Mawad H, et al. Improved assessment of bone turnover by the PTH-(1-84) large C-PTH fragments ratio in ESRD patients. Kidney Int. 2001;60(4):1460–1468. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urena P, Hruby M, Ferreira A, Ang KS, deVernejoul MC. Plasma total versus bone alkaline phosphatase as markers of bone turnover in hemodialysis patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1996;7(3):506–512. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V73506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swolin-Eide D, Hansson S, Larsson L, Magnusson P. The novel bone alkaline phosphatase B1x isoform in children with kidney disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2006;21(11):1723–1729. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salusky IB, Ramirez JA, Oppenheim W, Gales B, Segre GV, Goodman WG. Biochemical markers of renal osteodystrophy in pediatric patients undergoing CAPD/CCPD. Kidney Int. 1994;45(1):253–258. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziolkowska H, Paniczyk-Tomaszewska M, Debinski A, Polowiec Z, Sawicki A, Sieniawska M. Bone biopsy results and serum bone turnover parameters in uremic children. Acta Paediatr. 2000;89(6):666–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magnusson P, Degerblad M, Saaf M, Larsson L, Thoren M. Different responses of bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms during recombinant insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and during growth hormone therapy in adults with growth hormone deficiency. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1997;12(2):210–220. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magnusson P, Sharp CA, Farley JR. Different distributions of human bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms in serum and bone tissue extracts. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2002;325(1–2):59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malluche HH, Mawad HW, Monier-Faugere MC. Renal osteodystrophy in the first decade of the new millennium: analysis of 630 bone biopsies in black and white patients. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26(6):1368–1376. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magnusson P, Arlestig L, Paus E, et al. Monoclonal antibodies against tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase. Report of the ISOBM TD9 workshop. Tumour Biol. 2002;23(4):228–248. doi: 10.1159/000067254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]