Abstract

Endocannabinoids modulate a diverse array of functions including progenitor cell proliferation in the central nervous system, and odorant detection and food intake in the mammalian central olfactory system and larval Xenopus laevis peripheral olfactory system. However, the presence and role of endocannabinoids in the peripheral olfactory epithelium has not been examined in mammals. We found the presence of cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) and cannabinoid type 2 (CB2) receptor protein and mRNA in the olfactory epithelium. Using either immunohistochemistry or calcium imaging we localized CB1 receptors on neurons, glia like sustentacular cells, microvillous cells and progenitor-like basal cells. To examine the role of endocannabinoids, CB1 and CB2 receptor deficient (CB1−/−/CB2−/−) mice were used. The endocannabinoid 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG) was present at high levels in both C57BL/6 wildtype and CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice. 2-AG synthetic and degradative enzymes are expressed in wildtype mice. A small but significant decrease in basal cell and olfactory sensory neuron numbers was observed in CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice compared to wildtype mice. The decrease in olfactory sensory neurons did not translate to impairment in olfactory-mediated behaviors assessed by the buried food test and habituation/dishabituation test. Collectively, these data indicate the presence of an endocannabinoid system in the mouse olfactory epithelium. However, unlike in tadpoles, endocannabinoids do not modulate olfaction. Further investigation on the role of endocannabinoids in progenitor cell function in the olfactory epithelium is warranted.

Keywords: cannabinoids, 2-AG, olfaction, progenitor cells

1. Introduction

A cannabinoid system in the central olfactory system, i.e., main olfactory bulb, was first identified decades ago (Herkenham et al., 1991; Egertova and Elphick, 2000; Cesa et al., 2001; Egertova et al., 2003). In the mammalian olfactory bulb the two primary endocannabinoid ligands, N-arachidonoylethanolamide (AEA or anandamide) and 2-AG, are present and endocannabinoid synthesis enzymes are localized to neurons in the glomerular layer (Piomelli, 2003; Okamoto et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2012; Soria-Gomez et al., 2014). CB receptors are expressed in the granule cell layer of the olfactory bulb and in the glomerular layer where afferents from olfactory sensory neurons make their primary synapses (Wang et al., 2012). Only recently were cannabinoids identified in the peripheral olfactory system, i.e., the olfactory epithelium, of Xenopus laevis tadpoles (Migliarini et al., 2006; Czesnik et al., 2007). Tadpole CB1 receptors are expressed on dendrites of neurons and 2-AG is synthesized in both neurons and glial-like sustentacular cells (Czesnik et al., 2007; Breunig et al., 2010a). To date, an endocannabinoid system has not been described in the mammalian olfactory epithelium.

Endocannabinoids regulate neuronal activity and signaling in the glomeruli through canonical retrograde signaling and pre-synaptic inhibition (Wang et al., 2012). However, endocannabinoids also have a neuromodulatory role in the olfactory bulb and have been implicated in food intake (Di Marzo and Matias, 2005). A potential mechanism underlying sensory control of food intake is modulation of odorant sensitivity by endocannabinoids. In humans and other animals, sensitivity to and perceptual quality of food odorants are enhanced with hunger, and decrease with satiety (Berg et al., 1963; Crumpton et al., 1967; Aime et al., 2007). In addition, dysfunction of the olfactory system occurs in eating-related obesity in humans (Richardson et al., 2004). Clearly, the sense of smell may be important in regulating food intake, and metabolic signals such as endocannabinoids may be able to modulate olfactory functions.

Soria-Gomez and colleagues (2014) demonstrated that CB1 receptor activity in the olfactory bulb influences neuronal activation, odorant detection, and food intake in fasted mice. A behavioral assay scoring exploration time of increasing concentrations of an odorant (almond or banana) was used to show cannabinoid treatment (via direct injection into the olfactory bulb or increased AEA production) decreased the odorant concentration at which mice spent significant times exploring compared to vehicle treated mice (Soria-Gomez et al., 2014). Additionally, olfactory bulb specific CB1-receptor deficient mice displayed a physiological decrease in odorant detection threshold under vehicle conditions, suggesting that increased odorant detection in a fasted state is CB1 receptor-specific (Soria-Gomez et al., 2014). Mice with a selective CB1-receptor deficiency in the granule cell layer of the olfactory bulb ate less food 24 hours after fasting than fasted control mice (Soria-Gomez et al., 2014). Collectively, these data suggest that endocannabinoid signaling via CB1 receptors helps link the physiological state of hunger to odorant detection thresholds and food intake.

The peripheral olfactory epithelium is the site where odorants are detected (odorant threshold) and the central olfactory structures, the olfactory bulb and olfactory cortex, are involved in the identification and the discrimination of odorants (Enwere et al., 2004; Kovacs, 2004). The cannabinoid system modulates odorant-evoked responses in the peripheral olfactory epithelium in larval Xenopus (Czesnik et al., 2007; Breunig et al., 2010a). Odorant threshold sensitivity is increased when 2-AG synthetic enzyme diacylglycerol lipase α (DAGLα) is inhibited pharmacologically, suggesting that endogenous olfactory sensory neuron odorant sensitivity is mediated by the endocannabinoid 2-AG (Breunig et al., 2010b). Exogenous cannabinoid stimulation after fasting decreases odorant threshold, thereby enhancing odorant detection (Breunig et al., 2010b), suggesting a role in food intake.

The mouse olfactory epithelium is pseudostratified and contains multiple cell types. Olfactory sensory neurons have a cell soma located in the middle third of the epithelium and an unmyelinated axon that projects to the olfactory bulb. Non-neuronal sustentacular cells and microvillous cells have large cell bodies located in the upper third of the epithelium and thin cytoplasmic extensions that terminate in an endfoot process. Globose basal cells and horizontal basal cells are proliferative multipotent progenitor cells that lie near the basal lamina and give rise to both olfactory sensory neurons and non-neuronal cells (Holbrook et al., 1995; Huard et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2004). These progenitor basal cells proliferate, differentiate and mature to maintain homeostasis in the olfactory epithelium throughout life. The regulatory mechanisms of olfactory epithelium tissue homeostasis have not been clearly elucidated.

In the adult nervous system, the endocannabinoid system regulates progenitor stem cells in restricted neurogenic areas including the subventricular zone and dentate gyrus. Progenitor cell function is inhibited in CB receptor-deficient mice in these brain regions (Jin et al., 2004; Aguado et al., 2005). It is not known if endocannabinoids also regulate olfactory epithelium tissue homeostasis. CB receptor-mediated regulation of progenitor/stem cell number and fate could have functional and behavioral consequences for mice lacking these receptors. Here, we examined for the presence of an endocannabinoid system in the mouse olfactory epithelium. Using a CB1/CB2 deficient mouse model, we examined the hypothesis that cannabinoid receptor signaling regulates tissue homeostasis and olfactory-mediated behaviors.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1 Animals

Adult male (6–8 weeks old) Swiss Webster (CFW) and C57BL/6 wildtype control mice were obtained from Charles River, Portage, MI. Cannabinoid receptor 1 and cannabinoid receptor 2 deficient (CB1−/−/CB2−/−) mice were kindly provided by Dr. Norbert Kaminski (Michigan State University, MI) who obtained them from Dr. Andreas Zimmer (University of Bonn, Germany) (Jarai et al., 1999). Some of the experiments used mice in which the first exon of the Itpr3 gene was replaced by the coding region of a fusion protein of tau and green fluorescent protein (GFP), designated inositol triphosphate receptor 3 (IP3R3)-tauGFP mice (Hegg et al., 2010; Jia et al., 2013). Both heterozygous IP3R3+/−tauGFP−/+ and homozygous IP3R3−/−tauGFP+/+ mice allow for the visualization of a subtype of microvillous cells. Mice were given food and water ad libitum. Animal rooms were kept at 21–24°C and 40–60% relative humidity with a 12-h light/dark cycle. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as approved by Michigan State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2 Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

All reagents used for reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction were of molecular biology grade and were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI), unless otherwise noted. Anesthetized (65mg/kg ketamine with 5 mg/kg xylazine, i.p.) C57BL/6 and Swiss Webster (CFW) adult male animals were decapitated. The olfactory epithelia were immediately dissected and stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was isolated using Tri Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) and the polymerase chain reaction amplification was performed as previously described (Kaplan et al., 2005).

2.3 Western blot

Anesthetized adult male (6–8 weeks old; 65mg/kg ketamine with 5 mg/kg xylazine, i.p.) C57BL/6 mice were decapitated. The olfactory epithelia were immediately dissected and stored at −80 °C. The olfactory tissue was processed following the protocol described previously (Jia et al., 2009). Briefly, tissues were homogenized by sonication in Tris buffer. Homogenates (30μg/lane) were resolved on 12.5% gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were left overnight at 4 °C after incubation with the following primary antibodies made in blocking buffer (0.2% g/L I-Block, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA): rabbit anti-CB1-L15 antibody ([1:250], kind gift from Dr. Ken Mackie, Indiana University, Bloomington, IL, USA (Hajos et al., 2000)) rabbit anti-CB2 antibody ([1:200], Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), goat anti-DAGLα ([1:1000], Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), or rabbit anti-monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) ([1:500], Abcam). After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (Jackson Laboratory, West Grove, PA, USA). Immunoreactive proteins were detected with a chemiluminescence reagent (ECL, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and then exposed to Kodak X-ray film. Next, the blots were stripped with stripping buffer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and re-hybridized with mouse anti-actin antibody (1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) to control for variations in protein application or transfer.

2.4 Characterization of antibodies used to detect a cannabinoid system

The laboratory, company of origin, or other researchers characterized these antisera as follows. The rabbit anti-CB1 antibody, directed against the last 15 amino acids of the C-terminal tail, (1) demonstrated a lack of immunoreactivity in tissue of CB1 deficient mice, (2) detected a protein of the expected molecular weight in Western blots of rat brain homogenates, (3) labeled CB1 receptor-transfected but not control ATt20 cells (Ledent et al., 1999; Hajos et al., 2000; Katona et al., 2001). We detected a protein of the expected molecular size (see results). The rabbit anti-CB2R antibody, directed against amino acids 20–33 of the human N-terminus, (1) demonstrated a lack of immunoreactivity using immunohistochemistry in retinal tissue of CB2 receptor deficient mice (Duff et al., 2013), but not in brain (Baek et al., 2013), (2) detected proteins of the expected molecular weight in Western blots of retina, visual cortex and cerebellum, and did not detect proteins following preadsorption with the original antigen (Bouskila et al., 2013), and (3) showed immunoreactivity in Western blot analysis using CB2 receptor deficient mice (Cecyre et al., 2014). The goat anti-DAGLα, directed against C terminal amino acids 1031–1042, (1) demonstrated a lack of immunoreactivity in mouse cerebellum of DAGLα deficient mice (Carl Hobbs, King’s College London, United Kingdom; manufacturer’s product sheet) and 2) detected proteins of the expected molecular weight in Western blots. The rabbit anti-MAGL, directed against amino acids 1–14 detected proteins of the expected molecular weight in Western blots. Using these antibodies, we also detected proteins of the expected molecular size using Western Blot analysis (see results).

2.5 Immunohistochemistry

Untreated adult male (6–8 weeks old) C57BL/6 or IP3R3-τGFP mice were deeply anesthetized (65–80 mg/kg ketamine with 5–10 mg/kg xylazine), transcardially perfused with saline, and fixed with 4% g/L paraformaldehyde. Heads were decalcified in EDTA (0.5 M, pH = 8) for 5 days, cryoprotected with 30% g/L sucrose and embedded in Tissue Tek OCT (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA) as previously described (Jia et al., 2010). Frozen coronal sections of olfactory epithelium (20 μm) from level 3 of the mouse nasal cavity taken at the level of the second palatal ridge were obtained were collected using a cryostat and mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). Tissue sections were rehydrated with phosphate buffered saline, permeabilized with 0.01–0.3% ml/l triton x-100 and blocked with 10% normal donkey serum. Tissue sections were incubated with rabbit anti-CB1 antibody (1:500) or rabbit anti-MAGL antibody (1:50, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) over night at 4 °C. We did not find experimental conditions under which CB2 receptor antibody labeling was specific. Double-labeled immunohistochemistry sections were processed as described above with the addition of previously characterized antibodies directed against established cellular markers: goat anti-olfactory marker protein (OMP, 1:1000, Wako Chemical, Plano, TX, USA), mouse anti–mammalian achaete-schute homolog 1 (MASH1, 1:20, BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), rabbit anti-cytokeratin 5 or 18 (CK5 or CK 18, 1:100, Abcam), or rabbit anti-P75 (1:200, Abcam). Immunoreactivity was detected by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-goat, mouse or rabbit immunoglobin or TRITC-conjugated donkey anti-goat or anti-rabbit immunoglobin (1:50 or 1:200, Jackson Immunoresearch Lab, West Grove, PA, USA). Vectashield mounting medium for fluorescence (Vector, Burlingame, CA) was applied and in some instances, the nuclei were counterstained with Vectashield mounting medium for fluorescence with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA). Immunoreactivity was visualized on an Olympus FV1000 Confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA, USA). FITC or GFP, and CY3 or TRITC dyes were excited at 488 and 543 nm and low pass filtered at 505–525 and 560–620 nm, respectively. For detection of CK5, MAGL and MASH1, antigen retrieval was performed before permeabilization by heating sections in a citrate buffer (pH = 6) in a microwave oven (700 W; 2×6 minutes low power). After antigen retrieval, MAGL primary antibody was left overnight on a shaker in a 4°C cold room. Immunohistochemistry controls included omitting the primary antibody or the secondary antibody or preadsorping the antibody with the original antigen. No specific immunoreactivity was observed in any of the controls.

The number of CK5 positive or MASH1 positive in the ectoturbinate 2 and endoturbinate II on three consecutive coronal sections of olfactory epithelium was counted by an experimenter blinded to the treatments and genotypes (n = 3–6 mice/group). Data were normalized to the length of olfactory epithelium on which the immunopositive cells were scored and expressed as number per linear millimeter olfactory epithelium. A stereological approach was used to estimate the quantity of OMP positive neurons given their large numbers. The percent volume density of OMP positive cells was calculated in one coronal section of olfactory epithelium between levels 3 and 4 in each animal using STEPanizer® software at www.stepanizer.com (Tschanz et al., 2011). At six regions in the ectoturbinate 2, four locations in the endo-turbinate II and one location in the septum, a 250×250 μm 144-point overlay was randomly placed (total area analyzed = 62500 μm2/location). The volume density of OMP positive cells was determined by manual point counting and expressed as the percentage of the ratio of the number of test points hitting OMP-immunoreactive olfactory sensory neurons, divided by the total number of points hitting the olfactory epithelium.

2.6 Measurement of endocannabinoids

Anesthetized adult male (6–8 weeks old; 65mg/kg ketamine with 5 mg/kg xylazine, i.p.) wildtype C57BL/6 and CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice were decapitated. The olfactory epithelia were immediately dissected and stored at −80 °C until lipid extraction was performed as described previously in the brain (Patel et al., 2003). The amounts of the two primary endocannabinoids AEA and 2-AG, as well as three other fatty acid lipid mediators, palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), oleoylethanolamide (OEA), and 2-oxogluteric acid (2-OG) were determined using isotope-dilution, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry as described previously (Patel et al., 2005).

2.7 Solutions

Ringer’s solution contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose; pH 7.4, 290–320 mOsms. Probenecid (500 μM), an inhibitor of the organic anion transporter, was included to aid in the loading and retention of fluo-4 AM (Di et al., 1990; Manzini et al., 2008)(Di et al., 1990; Manzini et al., 2008). Odorant mixture included odorants n-amyl acetate, R-carvone, heptanal, cineole, and octanol (50 μM each) added directly to Ringer’s solution. Concentrated stocks of ATP (10 μM) and odorant mixes were made in Ringer’s solution and stored at −20 °C and reconstituted on the day of the experiment. Concentrated stocks of CB receptor agonist WIN 55212-2 (WIN, 5 μM), enantiomer WIN 55212-3 (5 μM), and CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 (5 μM) stocks were made in DMSO (1% final concentration DMSO) and stored at −20 °C and reconstituted and diluted in Ringer’s solution on the day of the experiment.

2.8 Calcium imaging of olfactory epithelium slices

Olfactory epithelium slices were prepared, loaded with fluo-4 AM calcium indicator dye (Life Technologies/Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) and imaged on an Olympus Fluoview 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) as previously described (Hegg et al., 2009). Briefly, slices were placed in a laminar flow chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) and perfused continuously with Ringer’s solution at a flow rate of 1.5–2.0 ml/minutes. Test solutions were applied using bath exchange and a small volume loop injector (200 μl). An argon ion laser was used for fluorescence excitation at 488 nm. Fluorescence emissions were filtered at 510 nm. Time series experiments were performed collecting 640× 256 pixel images at 0.2 – 1 Hz. Regions of interest were drawn around areas, presumably individual cells, which exhibited increases in calcium and analyzed using Fluoview software (FV10-ASW Version 3.0). The fluorometric signals obtained are expressed as change in relative fluorescence (F), ΔF/F = (F−F0)/F0, in which F0 is the basal fluorescence level (mean F of first 5 frames).

Experiments using CB receptor antagonists were performed by sequentially obtaining (1) initial control agonist-evoked calcium transients, (2) calcium transients evoked by co-application of agonist in the presence or absence of antagonists and (3) recovery agonist-evoked calcium transients. To be included in the data set, the peak amplitude of the recovery calcium transient had to be at least 75% of the initial transient amplitude. All data were normalized to the initial calcium transient. Paired Student’s t-tests were used to determine significant differences (p < 0.05) between the antagonist (AM251) peak amplitude and the recovery of agonist peak amplitude. In other experiments, ATP (10 μM), odorants (50 μM of each heptanal, cineole, R-carvone, octanol, and n-amyl acetate), inactive enantiomers, or Ringer’s physiological solution were superfused following CB receptor agonists. Cells that responded to Ringer’s solution were excluded from analysis.

2.9 Olfactory behavioral tests

For the buried food test, a trial was administered every other day for 7 days (4 trials total). C57BL/6 and CB1−/−/CB2−/− 6–8 week old male mice (n = 12 mice/group) were fasted 16–18 hours prior to each trial day. For the first 3 trials, a mouse was first acclimated in a cage filled only with fresh wood chip bedding for 5 minutes, transferred to a second cage for 5 minutes and then to a third cage that contained a piece of sugary cereal that was buried beneath the bedding in a randomly selected location. On the 4th trial, the sugary cereal was placed on the surface of bedding. The latency to uncovering and eating the buried food was measured. Trial 1 measures naïve olfactory-mediated finding, trial 2 and 3 examine improvement based on positive reinforcement received in the previous trials and indicate olfactory-mediated learning and memory, while trial 4 with visible cereal is used to assess locomotor activity. Only mice that could find the buried food within 5 minutes and eat the food were included in the data analysis. The average improvement factor was calculated as Σ(T1/T3)/n (Le Pichon et al., 2009).

The habituation/dishabituation test was performed and analyzed as described previously (Le Pichon et al., 2009). Briefly, C57BL/6 and CB1−/−/CB2−/− male mice (n = 11–16 mice/group) were acclimated in the test cage for 30 minutes with a clean dry cotton applicator inserted through the hole on the cage lid prior to the beginning of trials to reduce novelty-induced exploratory activity during the subsequent trials. Distilled water (100 μl), peppermint extract or almond extract (100 μl of 1:100 with distilled water, McCormick & Co., Hunt Valley, MD) was applied to a cotton applicator and inserted through the hole on the cage lid. For each trial an odorant was delivered for 2 minutes with a 30 second delay before the next trial began. The testing consisted of 3 trials of distilled water, 3 trials of peppermint, then 3 trials of almond. Investigation was defined as active sniffing within a 1 cm radius of the cotton applicator with the snout oriented towards the applicator. The cumulative investigation time during the 2 minutes odorant presentation was recorded by a single observer blind to genotypes. Investigation time for trial 1 was calculated for each animal as Σ[(Trial 1distilled water + Trial 1peppermint+Trial 1almond)]/3. Odorant habituation was assessed by analyzing the investigation times of repeated exposure to the same odorant. The habituation index for each animal was calculated as Σ[(Trial 3 distilled water)+(Trial 3 peppermint)+(Trial 3 almond)]/3. The cross-habituation index for each animal was calculated as Σ[Trial 1 peppermint-Trial 3 distilled water)+(Trial 1 almond-Trial 3 peppermint)]/2.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test, and one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni multiple comparison test was performed using Prism 5 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA). Two-way ANOVA or repeated-measures two-way ANOVA was performed followed by the Newman-Keul post hoc test using GB-Stat v9.0 (Dynamic Microsystems, Inc., Silver Spring, MD).

3. Results

3.1 CB receptor expression in the mouse olfactory epithelium

An endocannabinoid system has been identified peripherally in the tadpole olfactory epithelium (Czesnik et al., 2007) and centrally in the rodent olfactory bulb (Wang et al., 2012; Soria-Gomez et al., 2014); however, it is unknown if the rodent olfactory epithelium contains an endocannabinoid system. The present study sought to confirm the presence of CB1 receptors in the mouse olfactory epithelium. CB receptor mRNA and protein was measured in olfactory epithelium tissue from C57BL/6 and CFW adult mice. CB1 and CB2 receptor mRNA was present in both species of mice (Fig. 1A). Data are expressed in cycle threshold levels (i.e., the cycle number in which the florescence generated within a reaction crosses a set threshold), which is a relative measure of the concentration of target mRNA. Cycle threshold levels of both CB receptors were at moderate levels in both mouse species. Delta cycle threshold levels of CB1 receptor (CFW, 15.8; C57, 15.3) represents the cycle threshold value (CFW, 28.7; C57, 27.0) minus the internal control cycle threshold levels (18S: CFW, 12.9; C57, 11.6). CB2 receptors showed a similar cycle threshold value profile (CFW, 33.0, C57; 33.0) (Fig. 1A). Using Western blot analysis, CB1 receptor protein was detected at 60 kD and CB2 receptor protein at around 40 kD, further verifying the presence of both CB receptors in the mouse olfactory epithelium (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. mRNA and protein expression of cannabinoid receptors in mouse olfactory epithelium.

(A) RT-PCR cycle threshold (CT; solid and striped portion of bars) and ΔCT (striped portion of bars only) values for both the CB1 and CB2 receptors in Swiss Webster (CFW; white bars) and C57BL/6 (grey bars) mice. (B) Representative immunoblots for CB1 and CB2 receptors and actin in C57BL/6 mouse olfactory epithelium.

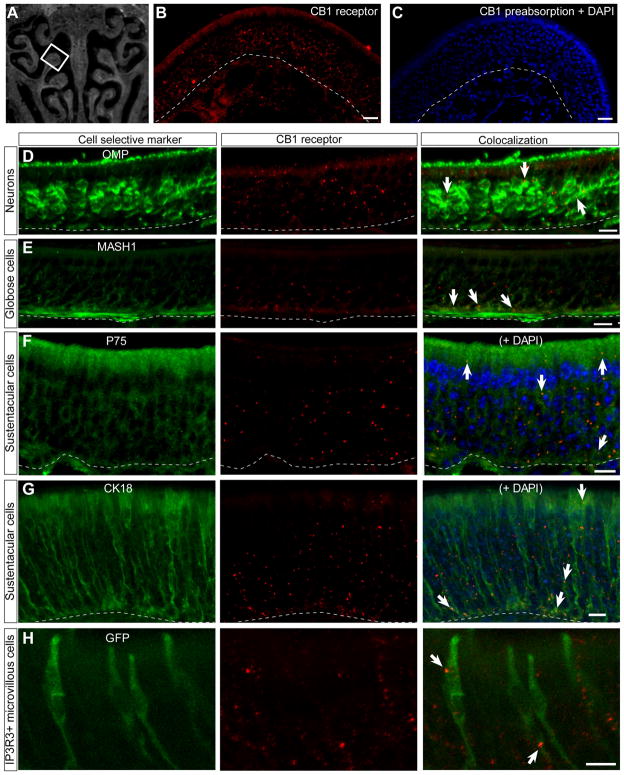

The distribution of CB1 receptor expression in the mouse olfactory epithelium was further examined using immunohistochemistry. Images for CB1 receptor immunoreactivity were chosen from ectoturbinate 2 in the mouse olfactory epithelium (Fig. 2A). Diffuse expression of CB1 receptor immunoreactivity was noted throughout the epithelium (Fig. 2B), suggesting CB1 receptor protein localization on multiple cell types. Preabsorption of the primary antibody with its immunizing peptide eliminated the CB1 immunoreactivity, indicating specificity of the CB1 antibody (Fig. 2C). CB1 receptor expression colocalized with olfactory sensory neuron specific antibody OMP in the neuronal layer of the olfactory epithelium (Fig. 2D). CB1 receptor immunoreactivity was also present in MASH-1 positive globose basal cells (Fig. 2E), suggesting that CB1 receptor action could influence basal cell proliferation in the mouse olfactory epithelium. CB1 receptor protein was also expressed in the non-neuronal sustentacular cells marked by P75 and CK18 antibodies (Fig. 2F–G). Microvillous cells also express the CB1 receptor protein as evidenced by colocalization with inositol triphosphate receptor 3 (IP3R3) expression observed in the IP3R3-tauGFP mouse (Fig. 2H). Notably, the distribution of CB1 receptors was not uniform through the layers of olfactory epithelium tissue. CB1 receptor immunoreactivity is found more frequently on the processes of olfactory sensory neurons and on the cytoplasmic extensions of sustentacular cells, rather than on the cell bodies. These are the first data to indicate the presence of CB receptors in the mouse olfactory epithelium.

Fig. 2. CB1 receptor expression is diffuse and co-localizes with multiple olfactory epithelium cell types.

(A) Representative coronal section through the C57/BL6 mouse nasal cavity at level 3. The endoturbinate II, indicated by a white box, is the region shown in panels B–G. (B) CB1 receptor immunoreactivity (red) is diffuse throughout the olfactory epithelium. (C) Preabsorption of the CB1 receptor antibody with the antigen eliminates immunoreactivity. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). (D–H) Immunoreactivity of cell selective markers (green, left column), CB1 receptor immunoreactivity (red, middle column) and co-localization (right column). CB1 receptor immunoreactivity co-localizes with (D) OMP+ olfactory sensory neurons, (E) MASH1+ subset of globose basal cells, (F–G) P75+ and CK18+ sustentacular cells shown with nuclei stained with DAPI (blue), and (H) IP3R3−/−GFP+/+ microvillous cells in ectoturbinate 3. Immunoreactivity of the CB1 receptor was similar in both heterozygous and homozygous IP3R3-tauGFP mice (data not shown). Arrows indicate location of CB1 receptor co-localization in some instances. Scale bar = 20 μm B,C; 10 μm D–H. Dashed white lines indicate basement membrane.

3.2 Endocannabinoid 2-AG is present in the mouse olfactory epithelium

Two main endocannabinoid ligands have been previously described in the central nervous system and olfactory systems. AEA, is present in pmol levels in the rodent brain, while 2-AG, is detected in nmol levels in the rodent brain, and pmol levels within the murine olfactory bulb and Xenopus laevis larval olfactory epithelium (Breunig et al., 2010b; Buczynski and Parsons, 2010; Soria-Gomez et al., 2014). Lipid extracts of endocannabinoids were quantified in the mouse olfactory epithelium (Table 1). High physiological levels of 2-AG were present in the olfactory epithelium of both C57BL/6 wildtype mice and CB1/CB2 receptor deficient mice, although no detectable levels of AEA were present in either tissue. Notably, the 2-AG levels in the mouse olfactory epithelium were in the nmol range, while the levels in tadpole olfactory epithelium levels were at pmol levels (Breunig et al., 2010b). Additionally, the 2-AG congener 2-OG and AEA congeners PEA and OEA were detected (Table 1). PEA and OEA are endogenous lipid signaling molecules proposed as members of the endocannabinoid family that share biosynthetic and metabolic pathways with AEA, but do not activate CB1 or CB2 receptors. The levels of endocannabinoids were similar in both C57BL/6 wildtype mice and CB1/CB2 receptor deficient mice, suggesting that endocannabinoid levels are not upregulated due to the loss of functional CB receptors. The metabolic enzymes involved in the synthesis and degradation of 2-AG were examined next. 2-AG synthesis enzyme diacylglycerol lipase α protein was present in the mouse olfactory epithelium (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the 2-AG degradation enzyme MAGL protein was present (Fig. 3B) and distributed throughout the mouse olfactory epithelium with notable immunoreactivity apically, possible in the knobs of olfactory sensory neurons (Fig. 3C). These data conclusively show that 2-AG is synthesized, present at physiological conditions, and degraded within the mouse olfactory epithelium.

Table 1.

Levels of endocannabinoids and select analogs in mouse olfactory C57BL/6 wildtype and CB1/CB2 receptor deficient (CB1−/−/CB2−/−) turbinate tissue (nmol/g tissue).

| 2-AG | 2-OG | OEA | PEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 wildtype | 26.49 | 8.95 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| CB1−/−/CB2−/− | 22.28 | 8.08 | 0.03 | 0.21 |

Fig. 3. 2-AG synthetic and degradative enzyme expression in the adult mouse olfactory epithelium.

(A–B) Western blot images from C57BL/6 mouse olfactory turbinate tissue showing 2-AG synthetic enzyme DAGLα (A) and 2-AG degradative enzyme MAGL (B). (C) Immunoreactivity of the hydrolytic endocannabinoid enzyme MAGL antibody is distributed throughout the olfactory epithelium (top), but is absent when the MAGL antibody is removed (bottom). Scale bar = 20 μm. Dashed white lines indicate basement membrane.

3.3 CB receptors are functional in the mouse olfactory epithelium

Calcium imaging was performed to further investigate location and functionality of the CB receptors. Endocannabinoids have low stability in solution, are easily oxidized when exposed to air, and hydrolyze rapidly in vivo (Smith et al., 2009). Therefore, the synthetic CB1 and CB2 receptor agonist WIN (5 μM), was applied to a neonatal mouse olfactory epithelium slice preparation loaded with the fluorescent calcium indicator dye fluo-4 AM. Reproducible increases in intracellular calcium (i.e., ± 25% of the initial peak calcium transient) were observed following 3 successive applications to WIN (5 μM) in 17% of the collective WIN-responsive cells (Fig. 4A; 161/929 cells from 36 slices). The inactive enantiomer WIN 55212-3 (5 μM) failed to elicit a response in 92.5% of WIN-responsive cells to which it was applied (346/374 cells from 13 slices; Fig. 4A). This lack of response was not due to linear run-down or tissue deterioration as no response was seen when the inactive enantiomer was given before WIN application. The percentage of cells that responded to the inactive enantiomer was less than the 8.7% of the WIN-responsive cells that also responded to Ringer’s physiological solution application (68/781cells from 34 slices). This observation likely reflects a small number of cells that respond to mechanical stimulation or exhibit spontaneous changes in calcium (Furuya et al., 1993; Hegg et al., 2009). The CB1 receptor specific antagonist AM251 (5 μM) was superfused over olfactory epithelium slices for 5 minutes prior to and during WIN application. AM251 did not induce calcium transients when applied to olfactory epithelium tissue alone (data not shown). AM251 significantly reduced the WIN-induced response by 30 ± 9% of the initial WIN calcium transient peak (Fig. 4B–C; 27 cells from 4 slices; p< 0.05). While we cannot rule out the contribution of the CB2 receptor or WIN-responsive TRP channels, these data indicate that at least part of the calcium transient was due to CB1 receptor activation.

Fig. 4. CB1 receptor activation induces calcium transients in mouse olfactory epithelium.

Confocal calcium imaging was performed from fluo-4AM loaded olfactory epithelium slices. (A) Representative traces of calcium transients from a single cell following successive applications of 5 μM WIN, 5 μM inactive WIN enantiomer, and control Ringer’s solution. In this figure and all subsequent figures ▲ indicates approximate time of drug superfusion, and breaks in traces correspond to 5 minute periods when images were not collected. (B) Representative calcium transients in a single cell due to superfusion with WIN, WIN application during superfusion of CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 (5 μM; 5 min), and WIN superfusion following washout with Ringer’s (recovery). (C) Bar graph depicting the normalized peak amplitudes of WIN-induced calcium transients in the presence or absence of AM251. (*, p<0.05 vs. recovery; Student’s t-test; n=27 regions of interest from 8 slices from 5 litters). (D–G) Images of fluo-4AM loaded olfactory epithelium slices with ATP-responsive cells (D) and odorant-responsive cells (G) marked by arrows. (E–F) Representative calcium transients evoked by successive applications of 5 μM WIN followed by 10 μM ATP (E) or a mixture of odorants (F).

Next, to determine which cell types were responsive to WIN application, cell morphology, localization, and responsiveness to other stimuli were used as indicators. Denoted olfactory sensory neurons were responsive to a mixture of odorants and had a cell soma in the middle of the epithelium, while non-neuronal cells (sustentacular cells or microvillous cells) had cell somas located in the upper 1/3 of the epithelium and were responsive to ATP, but not odorants. Using these parameters, 60% of WIN-responsive cells also responded to ATP (Fig. 4D–E; 732/1223 cells from 46 slices), while 21% responded to the odorant mixture (Fig. 4F–G; 256/1223 cells from 46 slices). Collectively, these data indicate that CB1 receptors are functional in the mouse olfactory epithelium in both neurons and non-neuronal cells.

3.4 Olfactory epithelium tissue composition in CB1/CB2 receptor deficient mice

A change in endocannabinoid signaling could alter the microenvironment and ultimately affect the behavior and function of the olfactory epithelium. To investigate possible morphological changes in the CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice, the complement of cells in the olfactory epithelium of adult C57BL/6 wildtype and CB1/CB2 receptor deficient mice was examined. Compared to C57BL/6 wildtype mice, the number of cells expressing cytokeratin 5 (CK5), located in horizontal basal cells and MASH1, a proneural transcription factor expressed in a subpopulation of global basal cells, was significantly reduced in the olfactory epithelium of CB1/CB2 receptor deficient mice compared to C57BL/6 wildtype (p<0.05, Fig. 5A,B,D,E). This indicates that there are fewer progenitor cells in the CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice, although horizontal basal cell numbers were only decreased 23% and globose basal cell numbers were decreased 26%. However, this decrease in basal cell numbers could be sufficient to induce changes in differentiated cell populations in the olfactory epithelium of CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice. Indeed, the number of OMP positive mature olfactory sensory neurons in CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice was significantly decreased (p< 0.05, Fig. 5C,F). This suggests that the pool of progenitor cells in the CB1−/−/CB2−/− mouse is not sufficient to maintain the number of mature neurons. Similar to the significant albeit slight decrease in basal cell numbers, CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice only exhibited a 16% decrease in OMP-positive cells compared to C57BL/6 wildtype. Collectively, these data indicate that a significant decrease in progenitor cell numbers leads to impaired differentiation and subsequent decrease in mature olfactory sensory neurons in the olfactory epithelium of CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice.

Fig. 5. CB1/CB2 receptor deficient mice have fewer cells in the olfactory epithelium.

(A–C) Representative immunoreactivity to cytokeratin 5 (CK5) positive horizontal basal cells (A), MASH1 positive globose basal cells (B), and OMP-positive neurons (C) in adult C57BL/6 mice (top row) and CB1/CB1 receptor deficient (CB1−/−/CB2−/−) mice (bottom row). DAPI (blue) demarcates the nuclei. Dashed white lines indicate basement membrane. Arrows indicate some instances of positive immunoreactivity. Scale bars = 10 μm. (D–F) Bar graphs depicting the number of CK5 positive horizontal basal cells (D) MASH1 positive globose basal cells (E) and OMP positive neurons (F) in the olfactory epithelium of adult C57BL/6 and CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice. (*, p<0.05 vs. respective C57BL/6 control; Student’s t-test for each cell marker; n = 12 sections from 4 mice).

3.5 Olfactory function in CB1/CB2 receptor deficient mice

The decrease in number of first order sensory neurons in the CB1−/−/CB2−/− mouse could adversely affect the ability to detect odorants. Thus, two olfactory-mediated behavioral tests were performed. In the buried food test, the latency to find a piece of buried food was measured over 3 trials in fasted untreated C57BL/6 wildtype and CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice (Fig. 6). The first trial measures the ability to detect novel odorants, while the subsequent trials measure olfactory-mediated learning and memory based on positive reinforcement from previous trials (Le Pichon et al., 2009). CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice exhibited a significant increase in the latency of trial 1, used to measure naïve olfactory-mediated investigation, compared to C57BL/6 wildtype mice (p<0.05; Fig. 6A). However, CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice exhibited a significant increase in the latency to approach a piece of visible food (p<0.05; Fig. 6B), indicating that the increased latency in trial 1 times in CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice could either be due to a deficit in olfaction or an overall decrease in mobility. Notably, a hallmark of CB1 receptor deficient mice is decreased locomotion resulting from the high density of CB receptors in the basal ganglia and cerebellar cortex (Zimmer et al., 1999; Elphick and Egertova, 2001). The average improvement factor, an indicator of olfactory-mediated learning and memory, was calculated as the ratio of trial 1 to trial 3 latencies. No change in improvement factor is seen in CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice, indicating that CB receptor deficiency does not impair olfactory learning and memory (Fig. 6C). Overall, the analysis of the latency to find buried food using a repeated measures two-way ANOVA showed that there were significant overall effects of repeated measure trials (F(2,22) = 7.52, p< 0.0016) as well as a genotype effect (F(1,23) = 8.50, p = 0.008), but no interaction between these measures. The significant overall effect on repeated measures suggests that the ability to find buried food in both C57BL/6 wildtype and CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice was improved due to the positive reinforcement of repetition as all mice had a reduced latency in trials 2 and 3.

Fig. 6. Olfactory-mediated behavioral assays in CB1/CB2 receptor deficient mice.

(A–C) Buried food behavioral tests were performed every other day in fasted C57BL/6 wildtype and CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice. Bar graphs show the average (± SEM) from CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice (dark bars) and C57BL/6 mice (white bars) for: (A) latency of trials 1–3 (*, p<0.05 for trial 1 compared to C57BL/6 wildtype, repeated measures two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey/Kramer Procedure post-hoc test; n = 11–16 mice per group), (B) latency of trial 4 with visible food, an assessment of locomotor activity (*, p<0.05; Student’s t-test; n = 10–12 mice per group), and (C) average improvement factor calculated as the ratio of trial 1 vs. trial 3 latencies, an indicator of olfactory-mediated learning and memory (p>0.05; Student’s t-test; n = 10–12 mice per group). (D–G) The olfactory habituation/dishabituation behavioral test was performed in C57BL/6 wildtype (WT) and CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice. (D) Investigation times in seconds (+SEM) for trials 1–3 for three odorants are shown. There were no differences between CB1−/−/CB2−/− and C57BL/6 mice in (E) the investigation time of the trial 1 odorants (the average for all three first odorants), (F) the habituation index, and (G) the ability to discriminate between odorants, measured by the cross-dishabituation index (p>0.05, Student’s t-test; n = 11–16 mice per group).

To further investigate if CB receptor signaling alters olfactory-mediated behaviors, a more sensitive behavioral assay was performed. The olfactory habituation/dishabituation test relies on the natural tendency to investigate novel smells and is used to examine the ability to detect and differentiate between different odorants (Sundberg et al., 1982; Yang and Crawley, 2009). Generally, mice spend more time on a novel odorant and less time on a previously investigated odorant. This test eliminates the factors associated with traditional operant odorant discrimination tests, such as cognitive or learning-dependent training, nutritional deprivation, and sensorimotor control, and is therefore used as a test of spontaneous odorant discrimination (Linster et al., 2002; Wesson et al., 2008). The habituation/dishabituation test includes the measurement of novel odorant investigation in the first trial, odorant habituation by exposure to the same odorant, and odorant dishabituation by exposure to a new odorant. Novel odorant investigation was measured by combining the investigation times of the first trial for each odorant (water1, peppermint1, almond1) in CB1−/−/CB2−/− and C57BL/6 wildtype mice (Fig. 6D). The pooled investigation times of trial 1 were similar between C57BL/6 wildtype and CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice, indicating no deficiency in novel odorant investigation (Fig. 6E). We next assessed odorant habituation over repeated odorant exposures. All mice showed decreases in investigation times in trials 2 and 3 (Fig. 6D; habituation) and an increase in investigation times with novel odorant presentation, trial 1 (Fig. 6D; dishabituation). There were no significant differences in the habituation index between C57BL/6 and CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice (Fig. 6F), indicating that all mice have a similar ability to habituate to repeated odorant exposure. The ability to discriminate odorants was assessed using the cross-habituation index, and no genotype differences were observed indicating CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice have the ability to discriminate between different odorants (Fig. 6G). Two-way ANOVA revealed no significant effect of genotype (F(1,36) = 3.68, p < 0.0632), but a significant main effect of repeated measures (F(1,29) = 9.75, p < .0001). Therefore, the sensitivity to novel odorant detection or odorant discrimination is not affected in CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice despite a significant loss in olfactory sensory neuron population compared to C57BL/6 wildtype mice.

4. Discussion

4.1 The endocannabinoid system in the mouse olfactory epithelium

We have identified a functional endocannabinoid system in the mouse olfactory epithelium for the first time. Previous studies described an endocannabinoid system in the rodent olfactory bulb (Wang et al., 2012) and the tadpole olfactory epithelium (Czesnik et al., 2007), specifically with neuronal expression of CB1 receptors. Here, the distribution of CB1 receptors has been identified in neuronal, non-neuronal, and basal progenitor cells in the mouse olfactory epithelium. The expression of CB1 receptors on all cell types in the mouse olfactory epithelium implies multiple functions for endocannabinoids in this peripheral system. CB1 receptors identified on mouse olfactory sensory neurons could indicate a neuromodulatory role for endocannabinoids in odorant detection, as previously demonstrated in the tadpole (Czesnik et al., 2007). However, our evidence showing no difference in whole animal olfactory-based behavioral assays in control and CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice indicates this is not likely. CB1 receptors located on mouse progenitor horizontal basal cells and globose basal cells coupled with the observation of a decrease in these cell populations in CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice indicates endocannabinoids may be involved in proliferation signaling, as the endocannabinoid system influences proliferation and neurogenesis in adult neurogenic regions of the CNS (Aguado et al., 2006; Compagnucci et al., 2013). CB1 receptor expression on non-neuronal cells indicates endocannabinoids could be involved in homeostatic regulation since sustentacular cells are capable of complex signaling pathways and function to provide physiological and metabolic support to the olfactory epithelium (Rodriguez et al., 2008; Hegg et al., 2009).

We were not expecting the detection of CB2 receptor protein in the olfactory epithelium. In the central and peripheral nervous system CB2 receptors are primarily expressed on the immune cells, specifically microglia and mast cells, respectively. In the olfactory epithelium, in the absence of damage or injury, there are very few immune cells present (Getchell et al., 2002). Further, the olfactory epithelium is avascular while the underlying lamina propria is vascular and is likely the source of immune cells that infiltrate the olfactory epithelium following injury, damage or pathogen invasion. Thus, we suspect that the positive CB2 receptor immunoblot was due to the presence of CB2 receptors on immune cells located in the lamina propria. Unfortunately, we were unable to confirm this using a CB2 receptor antibody specifically for immunohistochemistry due to problems with the specificity (Baek et al., 2013; Cecyre et al., 2014; Marchalant et al., 2014).

Endogenous cannabinoid signaling in the mouse olfactory epithelium is mediated by 2-AG given the expression of its synthetic enzyme DAGLα and degradative enzyme MAGL. Additionally, 2-AG is detected at high physiological levels in the mouse olfactory epithelium, over, 1,000 times the amount reported in the rodent olfactory bulb and tadpole olfactory epithelium (Breunig et al., 2010b; Soria-Gomez et al., 2014). 2-AG levels were similar between C57BL/6 wildtype and CB1−/−/CB2−/− receptor deficient mice, suggesting CB receptor availability does not influence endocannabinoid production. Such high levels of physiological 2-AG could suggest a role for homeostatic signaling or tonic release of endocannabinoids in addition to activity dependent synthesis. Calcium imaging studies done in the tadpole olfactory epithelium suggest a tonic release of cannabinergic substances (Czesnik et al., 2006). However, increases in 2-AG could result from experimental conditions, as phospholipid metabolites are known to rise within 15 seconds postmortem in rat brain tissue (Sugiura et al., 2001), likely caused by postischemic rises in the concentrations of free calcium (Kempe et al., 1996). Although here, olfactory epithelium tissue was frozen within 30 seconds of decapitation and therefore it is possible postmortem ischemic lipid breakdown could contribute to the high levels of 2-AG measured. However, 2-AG levels measured in the mouse olfactory epithelium are unlikely to be the result of collection artifact. In mouse olfactory epithelium tissue there were no detectable levels of AEA, which is also subject to postmortem increases, and yet small quantities of AEA were found in both rodent olfactory bulb and tadpole olfactory epithelium (Breunig et al., 2010b; Soria-Gomez et al., 2014). The experimental procedures used here are sensitive enough to detect AEA in the pmol/g whole brain (Patel et al., 2005) which is at the lower range of published AEA levels in any region of the brain (Buczynski and Parsons, 2010). A deuterated version of AEA is added to every sample, and these standards were detected in the mass spectrum for each sample. However, we cannot rule out that endogenous AEA could be present at concentrations below the detection limit of the assay.

Calcium imaging experiments were used to support localization of CB receptors. CB1 receptor specific antagonist AM251 reduced WIN-evoked calcium transients by 30% in a population of cells. WIN-evoked calcium transients were not completely blocked by the CB1 specific antagonist, suggesting that CB2 or other WIN-responsive receptors may be expressed in the olfactory epithelium. TRPA1 channels are expressed in the olfactory epithelium (Nakashimo et al., 2010) and are activated by WIN (Akopian et al., 2008) and therefore may have contributed to the calcium transients. Classically, CB receptors preferentially recruits Gi/oα proteins (Mackie and Stella, 2006) resulting in inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and a decrease in cAMP levels. Thus, these data demonstrating increases in intracellular calcium are interesting. In other systems, CB1 receptor activation can elicit a modest increase in calcium mediated by pertussis toxin sensitive Gi/o α and βγ proteins acting via phospholipase C to release calcium from intracellular stores (Filipeanu et al., 1997; Sugiura et al., 1997; Netzeband et al., 1999; Lograno and Romano, 2004). CB1 receptors have also been reported to recruit to Gs or Gq/11 α proteins in a ligand- and tissue-dependent manner (Childers et al., 1993; Lauckner et al., 2005). Cannabinoids are also known to activate other extracellular targets such as the TRPV1 transient receptor potential cation channel (Begg et al., 2005) and other G protein-coupled receptors such as GPCR55 (Sawzdargo et al., 1999), GPCR119 (Overton et al., 2006), and GPCR18 (Kohno et al., 2006). No conclusions can be made as to which signaling pathway is activated during WIN-induced calcium transient in the mouse OE.

4.2 Function of the endocannabinoid system in the mouse OE

Both CB receptors regulate various protein kinase cascades involved in cell proliferation and survival, thus both CB receptor subtypes could functionally affect progenitor cell proliferation and cell fate decisions (Galve-Roperh et al., 2013). The number of horizontal basal cells and globose basal cells is decreased in the CB1−/−/CB2−/− mouse. As in the developing brain, endocannabinoid signaling via CB1 receptors on basal cells could help maintain basal cell population and self-renewal. The number of olfactory sensory neurons was also decreased in CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice, either reflecting the reduction in survival of the basal cell population or possible alterations in differentiation. Similar cell population profiles as observed in the CB1−/−/CB2−/− mouse are seen in genetic mouse models in which trophic factor receptors have been ablated. For example, in NPY receptor Y1-null mice there is a significant decrease in mature olfactory sensory neurons and MASH1 positive basal progenitor cells (Hansel et al., 2001; Doyle et al., 2008). In a mouse lacking the IP3R3, a receptor that contributes to the release of neurotrophic factor NPY through non-neuronal microvillous cells, a decrease in both globose basal cells and horizontal basal cells is seen (Jia et al., 2013). These similarities suggest that endocannabinoids play a role in neural progenitor cell homeostasis. The decrease in OMP positive cells in the CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice suggests that endocannabinoid signaling also influences neuronal differentiation under physiological conditions.

Due to the loss of neurons in the CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice, we examined CB receptor-dependent changes in mouse olfactory function using olfactory-mediated behavioral assays. The buried food test, which relies on the natural tendency to use olfactory cues for foraging, tests the ability to smell volatile odorants (Yang and Crawley, 2009). CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice exhibited prolonged latencies to detect a buried odorant (i.e., food), which reflects impairment in olfaction. However, CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice also showed decreased locomotion when visible food was presented. This could reflect the previously characterized decreases in mobility and increases in freezing behavior seen in CB1 receptor deficient mice (Zimmer et al., 1999). Given the 16% loss of olfactory sensory neurons in CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice, it is possible that these mice exhibit natural impairments in olfaction and sporadic decreases in locomotion. During trials 2 and 3, CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice did not exhibit increased latencies to detected buried food, suggesting impairments in mobility were not consistent throughout each trial compared to C57BL/6 wildtype controls. Therefore, it is likely that trial 1 increases in latency are olfactory-mediated.

Due to the inconclusive results from the buried food test, the olfactory habituation/dishabituation test was used to examine novel odorant investigation, odorant discrimination and odorant habituation. A single sniff of an odorant is sufficient for odorant detection and discrimination (Wesson et al., 2008), while prolonged sniffing response is an indicator of arousal and motivation (Linster et al., 2002; Wachowiak et al., 2009). The olfactory habituation/dishabituation assay is sensitive and can discern the ability to discriminate subtle differences between 2 structurally similar odorants, such as enantiomers, (Moreno et al., 2009; Zou et al., 2012), between urinary odors of different genders (Pankevich et al., 2004; Jakupovic et al., 2008; Zou et al., 2013), and between urinary odors of different individuals of the same gender (Zou et al., 2013). This assay can also be used as a more sensitive test for distinguishing different concentrations of the same odor (Breton-Provencher et al., 2009; Soria-Gomez et al., 2014). The present study demonstrated no differences between C57BL/6 wildtype and CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice in novel odorant investigation or in odorant habituation or dishabituation, activities associated with the central olfactory structures (Enwere et al., 2004; Kovacs, 2004). Collectively, these data indicate that the absence of CB receptors did not affect odorant sensitivity despite significant decreases in number of olfactory sensory neurons.

Our behavioral data is in contrast to previous studies. Soria-Gomez and colleagues (2014) demonstrated that activation of CB1 receptors in the olfactory bulb increases odorant detection 24 hours after fasting. Similarly, Breunig and colleagues (2010b) reported that CB1 receptor activation increases odorant detection after 24 hours of fasting in the tadpole olfactory epithelium. In the current experiments, mice were only fasted overnight (~ 16 hours) to insure proper motivation to perform olfactory-mediated tasks. It is possible that different signaling mechanisms come into play in 24 hour fasted mice that are not seen in mice fasted overnight. Finally, in humans, administration of the CB receptor agonist tetrahydrocannabinol decreased odorant detection (Walter et al., 2014). Despite this modulatory effect in humans, Lötsch and Hummel (2015) have noted an important consideration regarding the role of cannabinoids in chemosensory processing: the CB1 receptor has yet to be found in human olfactory bulb and epithelium tissue. This raises the question of whether a functional homolog to the CB1 receptor is present in the human that could account for the alteration in olfaction following cannabinoid administration. In addition, it highlights the potential problems of directly translating mechanisms from the mouse model to humans, and supports the importance of translational studies.

5. Conclusions

Here, we provide the first identification of a functional cannabinoid system in the mouse olfactory epithelium that consists of CB1 receptor expression on multiple cell types and a very high unstimulated level of endocannabinoid 2-AG. CB receptor signaling likely contributes to the survival and proper regulation of the basal cell population, given the decrease in both horizontal basal cell and globose basal cell numbers in the CB1−/−/CB2−/− mouse. A future report will detail the further investigation of this observation. A decrease was also seen in olfactory sensory neuron numbers in the CB1−/−/CB2−/− mouse, although the remaining population of neurons was sufficient to adequately perform olfactory-mediated behaviors. This suggests olfactory signaling can adapt within the constraints of a limited olfactory sensory neuron population. Cannabinoid signaling in olfaction could be further investigated under altered physiological conditions, such as hunger state, or under pathophysiological conditions seen in advanced aging or with neurological disease.

Mouse olfactory epithelium (OE) has CB1 receptors on: neurons, glia, progenitor cells

2-arachidonylglycerol and its synthetic and degradation enzymes are present

CB1 and CB2 deficient mice have fewer progenitor cells and neurons in the OE

Loss of OE neurons in CB1 and CB2 deficient mice does not lead to olfaction deficits

Endocannabinoids do not modulate olfactory sensitivity in the mouse

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by NIH DA033495, MSU institutional funds, and the Research and Education Program, a component of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin endowment at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Ken Mackie (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA) graciously supplied the rabbit anti-CB1 antibody and Norbert Kaminski (Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA) supplied the CB1−/−/CB2−/− mice. We thank Brian Jespersen, and the Pharmacology and Toxicology Departmental Core Facilities for technical support.

Abbreviations

- CB1

cannabinoid type 1 receptor

- CB2

cannabinoid type 2 receptor

- CB1−/−/CB2−/−

CB1 and CB2 deficient

- 2-AG

2-arachidonylglycerol

- AEA

N-arachidonoylethanolamide

- DAGLα

diacylglycerol lipase α

- IP3R3

Inositol triphosphate receptor 3

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- MAGL

monoacylglycerol lipase

- OMP

olfactory marker protein

- MASH1

mammalian achaete-schute homolog 1

- CK

cytokeratin

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- PEA

palmitoylethanolamide

- OEA

oleoylethanolamide

- 2-OG

2-oxogluteric acid

- WIN

WIN 55212-2

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Chelsea Hutch, Email: hutchche@umich.edu.

Cecilia J. Hillard, Email: chillard@mcw.edu.

Cuihong Jia, Email: JIAC01@mail.etsu.edu.

Colleen C. Hegg, Email: hegg@msu.edu.

References

- Aguado T, Monory K, Palazuelos J, Stella N, Cravatt B, Lutz B, Marsicano G, Kokaia Z, Guzman M, Galve-Roperh I. The endocannabinoid system drives neural progenitor proliferation. FASEB J. 2005;19:1704–1706. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3995fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguado T, Palazuelos J, Monory K, Stella N, Cravatt B, Lutz B, Marsicano G, Kokaia Z, Guzman M, Galve-Roperh I. The endocannabinoid system promotes astroglial differentiation by acting on neural progenitor cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1551–1561. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3101-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aime P, Duchamp-Viret P, Chaput MA, Savigner A, Mahfouz M, Julliard AK. Fasting increases and satiation decreases olfactory detection for a neutral odor in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2007;179:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akopian AN, Ruparel NB, Patwardhan A, Hargreaves KM. Cannabinoids desensitize capsaicin and mustard oil responses in sensory neurons via TRPA1 activation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1064–1075. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1565-06.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek JH, Darlington CL, Smith PF, Ashton JC. Antibody testing for brain immunohistochemistry: Brain immunolabeling for the cannabinoid CB2 receptor. J Neurosci Meth. 2013;216:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg M, Pacher P, Batkai S, Osei-Hyiaman D, Offertaler L, Mo FM, Liu J, Kunos G. Evidence for novel cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;106:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg HW, Pangborn RM, Roessler EB, Webb AD. Influence of hunger on olfactory acuity. Nature. 1963;197:108. doi: 10.1038/197108a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouskila J, Javadi P, Casanova C, Ptito M, Bouchard JF. Muller cells express the cannabinoid CB2 receptor in the vervet monkey retina. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:2399–2415. doi: 10.1002/cne.23333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton-Provencher V, Lemasson M, Peralta MR, 3rd, Saghatelyan A. Interneurons produced in adulthood are required for the normal functioning of the olfactory bulb network and for the execution of selected olfactory behaviors. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15245–15257. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3606-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breunig E, Czesnik D, Piscitelli F, Di Marzo V, Manzini I, Schild D. Endocannabinoid modulation in the olfactory epithelium. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2010a;52:139–145. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-14426-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breunig E, Manzini I, Piscitelli F, Gutermann B, Di Marzo V, Schild D, Czesnik D. The endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol controls odor sensitivity in larvae of Xenopus laevis. J Neurosci. 2010b;30:8965–8973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4030-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczynski MW, Parsons LH. Quantification of brain endocannabinoid levels: methods, interpretations and pitfalls. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:423–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00787.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecyre B, Thomas S, Ptito M, Casanova C, Bouchard JF. Evaluation of the specificity of antibodies raised against cannabinoid receptor type 2 in the mouse retina. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2014;387:175–184. doi: 10.1007/s00210-013-0930-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesa R, Mackie K, Beltramo M, Franzoni MF. Cannabinoid receptor CB1-like and glutamic acid decarboxylase-like immunoreactivities in the brain of Xenopus laevis. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;306:391–398. doi: 10.1007/s004410100461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Fang H, Schwob JE. Multipotency of purified, transplanted globose basal cells in olfactory epithelium. J Comp Neurol. 2004;469:457–474. doi: 10.1002/cne.11031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers SR, Pacheco MA, Bennett BA, Edwards TA, Hampson RE, Mu J, Deadwyler SA. Cannabinoid receptors: G-protein-mediated signal transduction mechanisms. Biochem Soc Symp. 1993;59:27–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagnucci C, Di Siena S, Bustamante MB, Di Giacomo D, Di Tommaso M, Maccarrone M, Grimaldi P, Sette C. Type-1 (CB1) cannabinoid receptor promotes neuronal differentiation and maturation of neural stem cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumpton E, Wine DB, Drenick EJ. Effect of prolonged fasting on olfactory threshold. Psychol Rep. 1967;21:692. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1967.21.2.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czesnik D, Kuduz J, Schild D, Manzini I. ATP activates both receptor and sustentacular supporting cells in the olfactory epithelium of Xenopus laevis tadpoles. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:119–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czesnik D, Schild D, Kuduz J, Manzini I. Cannabinoid action in the olfactory epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2967–2972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609067104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Matias I. Endocannabinoid control of food intake and energy balance. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:585–589. doi: 10.1038/nn1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di VF, Steinberg TH, Silverstein SC. Inhibition of Fura-2 sequestration and secretion with organic anion transport blockers. Cell Calcium. 1990;11:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle KL, Karl T, Hort Y, Duffy L, Shine J, Herzog H. Y1 receptors are critical for the proliferation of adult mouse precursor cells in the olfactory neuroepithelium. J Neurochem. 2008;105:641–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff G, Argaw A, Cecyre B, Cherif H, Tea N, Zabouri N, Casanova C, Ptito M, Bouchard JF. Cannabinoid receptor CB2 modulates axon guidance. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egertova M, Cravatt BF, Elphick MR. Comparative analysis of fatty acid amide hydrolase and cb(1) cannabinoid receptor expression in the mouse brain: evidence of a widespread role for fatty acid amide hydrolase in regulation of endocannabinoid signaling. Neuroscience. 2003;119:481–496. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egertova M, Elphick MR. Localisation of cannabinoid receptors in the rat brain using antibodies to the intracellular C-terminal tail of CB. J Comp Neurol. 2000;422:159–171. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000626)422:2<159::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elphick MR, Egertova M. The neurobiology and evolution of cannabinoid signalling. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:381–408. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enwere E, Shingo T, Gregg C, Fujikawa H, Ohta S, Weiss S. Aging results in reduced epidermal growth factor receptor signaling, diminished olfactory neurogenesis, and deficits in fine olfactory discrimination. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8354–8365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2751-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipeanu CM, de Zeeuw D, Nelemans SA. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol activates [Ca2+]i increases partly sensitive to capacitative store refilling. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;336:R1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya K, Enomoto K, Yamagishi S. Spontaneous calcium oscillations and mechanically and chemically induced calcium responses in mammary epithelial cells. Pflugers Arch. 1993;422:295–304. doi: 10.1007/BF00374284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galve-Roperh I, Chiurchiu V, Diaz-Alonso J, Bari M, Guzman M, Maccarrone M. Cannabinoid receptor signaling in progenitor/stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52:633–650. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getchell TV, Subhedar NK, Shah DS, Hackley G, Partin JV, Sen G, Getchell ML. Chemokine regulation of macrophage recruitment into the olfactory epithelium following target ablation: involvement of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:784–793. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajos N, Katona I, Naiem SS, MacKie K, Ledent C, Mody I, Freund TF. Cannabinoids inhibit hippocampal GABAergic transmission and network oscillations. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3239–3249. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel DE, Eipper BA, Ronnett GV. Neuropeptide Y functions as a neuroproliferative factor. Nature. 2001;410:940–944. doi: 10.1038/35073601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegg CC, Irwin M, Lucero MT. Calcium store-mediated signaling in sustentacular cells of the mouse olfactory epithelium. Glia. 2009;57:634–644. doi: 10.1002/glia.20792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegg CC, Jia C, Chick WS, Restrepo D, Hansen A. Microvillous cells expressing IP3R3 in the olfactory epithelium of mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:1632–1645. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. Characterization and localization of cannabinoid receptors in rat brain: a quantitative in vitro autoradiographic study. J Neurosci. 1991;11:563–583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00563.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook EH, Szumowski KE, Schwob JE. An immunochemical, ultrastructural, and developmental characterization of the horizontal basal cells of rat olfactory epithelium. J Comp Neurol. 1995;363:129–146. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huard JM, Youngentob SL, Goldstein BJ, Luskin MB, Schwob JE. Adult olfactory epithelium contains multipotent progenitors that give rise to neurons and non-neural cells. J Comp Neurol. 1998;400:469–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupovic J, Kang N, Baum MJ. Effect of bilateral accessory olfactory bulb lesions on volatile urinary odor discrimination and investigation as well as mating behavior in male mice. Physiol Behav. 2008;93:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarai Z, Wagner JA, Varga K, Lake KD, Compton DR, Martin BR, Zimmer AM, Bonner TI, Buckley NE, Mezey E, Razdan RK, Zimmer A, Kunos G. Cannabinoid-induced mesenteric vasodilation through an endothelial site distinct from CB1 or CB2 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14136–14141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C, Doherty JD, Crudgington S, Hegg CC. Activation of purinergic receptors induces proliferation and neuronal differentiation in Swiss Webster mouse olfactory epithelium. Neuroscience. 2009;163:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C, Hayoz S, Hutch CR, Iqbal TR, Pooley AE, Hegg CC. An IP3R3- and NPY-expressing microvillous cell mediates tissue homeostasis and regeneration in the mouse olfactory epithelium. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Xie L, Kim SH, Parmentier-Batteur S, Sun Y, Mao XO, Childs J, Greenberg DA. Defective adult neurogenesis in CB1 cannabinoid receptor knockout mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:204–208. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan BL, Ouyang Y, Rockwell CE, Rao GK, Kaminski NE. 2-Arachidonoyl-glycerol suppresses interferon-gamma production in phorbol ester/ionomycin-activated mouse splenocytes independent of CB1 or CB2. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:966–974. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1104652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Rancz EA, Acsady L, Ledent C, Mackie K, Hajos N, Freund TF. Distribution of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in the amygdala and their role in the control of GABAergic transmission. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9506–9518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09506.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempe K, Hsu FF, Bohrer A, Turk J. Isotope dilution mass spectrometric measurements indicate that arachidonylethanolamide, the proposed endogenous ligand of the cannabinoid receptor, accumulates in rat brain tissue post mortem but is contained at low levels in or is absent from fresh tissue. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17287–17295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno M, Hasegawa H, Inoue A, Muraoka M, Miyazaki T, Oka K, Yasukawa M. Identification of N-arachidonylglycine as the endogenous ligand for orphan G-protein-coupled receptor GPR18. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347:827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs T. Mechanisms of olfactory dysfunction in aging and neurodegenerative disorders. Ageing Res Rev. 2004;3:215–232. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauckner JE, Hille B, Mackie K. The cannabinoid agonist WIN55,212-2 increases intracellular calcium via CB1 receptor coupling to Gq/11 G proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:19144–19149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509588102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Pichon CE, Valley MT, Polymenidou M, Chesler AT, Sagdullaev BT, Aguzzi A, Firestein S. Olfactory behavior and physiology are disrupted in prion protein knockout mice. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:60–69. doi: 10.1038/nn.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledent C, Valverde O, Cossu G, Petitet F, Aubert JF, Beslot F, Bohme GA, Imperato A, Pedrazzini T, Roques BP, Vassart G, Fratta W, Parmentier M. Unresponsiveness to cannabinoids and reduced addictive effects of opiates in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Science. 1999;283:401–404. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linster C, Johnson BA, Morse A, Yue E, Leon M. Spontaneous versus reinforced olfactory discriminations. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6842–6845. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06842.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lograno MD, Romano MR. Cannabinoid agonists induce contractile responses through Gi/o-dependent activation of phospholipase C in the bovine ciliary muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;494:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotsch J, Hummel T. Cannabinoid-related olfactory neuroscience in mice and humans. Chem Senses. 2015;40:3–5. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bju054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K, Stella N. Cannabinoid receptors and endocannabinoids: evidence for new players. AAPS J. 2006;8:E298–306. doi: 10.1007/BF02854900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzini I, Schweer TS, Schild D. Improved fluorescent (calcium indicator) dye uptake in brain slices by blocking multidrug resistance transporters. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;167:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchalant Y, Brownjohn PW, Bonnet A, Kleffmann T, Ashton JC. Validating Antibodies to the Cannabinoid CB2 Receptor: Antibody Sensitivity Is Not Evidence of Antibody Specificity. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014;62:395–404. doi: 10.1369/0022155414530995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliarini B, Marucci G, Ghelfi F, Carnevali O. Endocannabinoid system in Xenopus laevis development: CB1 receptor dynamics. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1941–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MM, Linster C, Escanilla O, Sacquet J, Didier A, Mandairon N. Olfactory perceptual learning requires adult neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17980–17985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907063106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashimo Y, Takumida M, Fukuiri T, Anniko M, Hirakawa K. Expression of transient receptor potential channel vanilloid (TRPV) 1–4, melastin (TRPM) 5 and 8, and ankyrin (TRPA1) in the normal and methimazole-treated mouse olfactory epithelium. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130:1278–1286. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2010.489573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzeband JG, Conroy SM, Parsons KL, Gruol DL. Cannabinoids enhance NMDA-elicited Ca2+ signals in cerebellar granule neurons in culture. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8765–8777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08765.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y, Wang J, Morishita J, Ueda N. Biosynthetic pathways of the endocannabinoid anandamide. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4:1842–1857. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton HA, Babbs AJ, Doel SM, Fyfe MC, Gardner LS, Griffin G, Jackson HC, Procter MJ, Rasamison CM, Tang-Christensen M, Widdowson PS, Williams GM, Reynet C. Deorphanization of a G protein-coupled receptor for oleoylethanolamide and its use in the discovery of small-molecule hypophagic agents. Cell Metab. 2006;3:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankevich DE, Baum MJ, Cherry JA. Olfactory sex discrimination persists, whereas the preference for urinary odorants from estrous females disappears in male mice after vomeronasal organ removal. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9451–9457. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2376-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Carrier EJ, Ho WS, Rademacher DJ, Cunningham S, Reddy DS, Falck JR, Cravatt BF, Hillard CJ. The postmortal accumulation of brain N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide) is dependent upon fatty acid amide hydrolase activity. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:342–349. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400377-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Rademacher DJ, Hillard CJ. Differential regulation of the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2-arachidonylglycerol within the limbic forebrain by dopamine receptor activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:880–888. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.054270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D. The molecular logic of endocannabinoid signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:873–884. doi: 10.1038/nrn1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson BE, Vander Woude EA, Sudan R, Thompson JS, Leopold DA. Altered olfactory acuity in the morbidly obese. Obes Surg. 2004;14:967–969. doi: 10.1381/0960892041719617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez S, Sickles HM, Deleonardis C, Alcaraz A, Gridley T, Lin DM. Notch2 is required for maintaining sustentacular cell function in the adult mouse main olfactory epithelium. Dev Biol. 2008;314:40–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawzdargo M, Nguyen T, Lee DK, Lynch KR, Cheng R, Heng HH, George SR, O’Dowd BF. Identification and cloning of three novel human G protein-coupled receptor genes GPR52, PsiGPR53 and GPR55: GPR55 is extensively expressed in human brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;64:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]