Abstract

Purpose

To demonstrate the presence of MT asymmetry in human cervical spinal cord due to the interaction between bulk water and semisolid macromolecules (conventional MT), and the chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) effect.

Materials and methods

MT asymmetry in the cervical spinal cord (C3/C4 - C5) was investigated in 14 healthy male subjects with a 3T magnetic resonance (MR) system. Both spin-echo (SE) and gradient-echo (GE) echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequences, with low power off-resonance radiofrequency irradiation at different frequency offsets, were used.

Results

Our results show that the z-spectrum in gray/white matter is asymmetrical about the water resonance frequency in both SE-EPI and GE-EPI, with a more significant saturation effect at the lower frequencies (negative frequency offset) far away from water and at the higher frequencies (positive offset) close to water. These are attributed mainly to the conventional MT and CEST effects respectively. Furthermore, the amplitude of MT asymmetry is larger in SE-EPI sequence than in GE-EPI sequence in the frequency range of amide protons.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate the presence of MT asymmetry in human cervical spinal cord, which is consistent with the ones reported in the brain.

Keywords: magnetization transfer, asymmetry, CEST, APT, spinal cord

Introduction

The protons in solid-like macromolecules and mobile proteins in tissues can be selectively saturated by an off-resonance magnetization transfer (MT) pre-pulse in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). It allows indirect detection of solid-like macromolecules through the exchange coupling of magnetization between the spins associated with bulk water and macromolecules by detecting the water signal intensity (1–4). The so-called magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) and z-spectrum (3) are commonly used to describe the magnitude of MT effect at different frequency offsets. Several quantitative models of MT have been proposed, among which Henkelman’s two-pool model is one of the most widely used (5). In many of these models, it has been generally assumed that the resonant frequency of the bulk water is the same as the solid-like macromolecules, which leads to symmetric z-spectra. However, recent research suggested that this assumption might not be valid. In particular, several studies have demonstrated asymmetrical z-spectra around the water resonance in different tissues (6–13). There are two types of MT asymmetry as reported. The first is associated with the conventional MT effect about the interaction between bulk water and semisolid macromolecules (conventional MT asymmetry) (6–9). It has been pointed out that in the brain, the z-spectra in tissue are slightly asymmetric around the water proton resonance frequency, with the center of the z-spectrum shifted slightly upfield (i.e. towards the lower frequency) from the water resonance (6–8). The second type of MT asymmetry is due to the chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) effect associated with exchangeable protons of some side groups e.g. −OH, −SH, and −NH (10–13). The saturation transfer takes place at a particular frequency corresponding to the magnetic resonance of the exchangeable protons. The saturated solute protons are replaced repeatedly by the non-saturated water protons, and when the former accumulate in the water pool, there is saturation amplification (14) leading to an asymmetrical z-spectrum. Understanding the conventional MT asymmetry and CEST is important for clinical purposes, as they can help provide different contrast to certain types of pathology. Recently, it has also been reported that the MT asymmetry in 9L rat brain tumors is different from that in contralateral normal-appearing brain tissue (8,15), which implies the feasibility of using MT asymmetry for tissue characterization as well. In the current study, these two types of MT asymmetry effects around water resonance are investigated in human cervical spinal cord using a 3T MR system.

Materials and methods

Theory

The z-spectrum plots the ratio of water signal intensities with and without the MT pulse as a function of frequency offset of the RF irradiation pulse. i.e. Msat(offset) / M0 versus frequency offset of the MT pre-pulse, where Msat(offset) is the detected water magnetization with MT pre-pulse at a particular frequency offset, and M0 is the one without the pre-pulse. To study the magnitude of the magnetization transfer effect, the magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) can be calculated using:

The MT asymmetry spectrum can be calculated by subtracting the MTR obtained at the negative offsets with respect to water from those at the corresponding positive offsets. Therefore, MTRasym is defined as:

Subjects

Fourteen healthy male subjects, aged between 19–29 years (22.4 ± 2.5 years) were recruited in this study. Each participating subject gave fully informed consent prior to the experiment. The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the institution where the study was carried out. For screening, sagittal T2-weighted and T1-weighted images were acquired before the study.

Scanning

Subjects were scanned on a 3T MRI scanner (Philips Achieva) with a multi-element spine coil as a receive coil and a Q-body coil as transmit coil. Four axial slices were acquired, with each one placed at either vertebral or disc level from C3/C4 to C5. Single shot spin-echo echo-planar imaging (SE-EPI) and gradient-echo EPI (GE-EPI) with one MT pre-pulse (pulse shape: block, saturation power: 2μT, saturation duration: 500ms) were used with frequency offsets from −80ppm to 80ppm. The frequency step was 5ppm between 10ppm and 80ppm, and 0.5ppm between 0ppm and 8ppm. For SE-EPI, the flip angle was set at 90 degrees, and the echo time (TE) was 31ms. In order to decrease the oblique flow displacement artifact from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the pre-phasing gradient lobe for phase-encoding was placed after the 180 degrees refocusing pulse (16). For GE-EPI, the flip angle was 70 degrees and TE was 9.7ms. Other common imaging parameters were as follows: field of view (FOV) = 80 * 36mm2, voxel size = 1 * 1.24 * 7mm3, repetition time (TR) = 2 heart beats, number of excitations (NEX) = 1, half scan factor ≈ 0.8, high-order shimming was on, fat saturation was applied, and Vectorcardiogram (VCG) triggering was used. The scanning time for SE-EPI and GE-EPI was around 8 minutes for each sequence.

Post-processing

Two dimensional rigid-body registration with three degrees of freedom was performed on the data volumes to eliminate the bulk motion effect using the software AIR (17). To minimize the B0 field inhomogeneity problem, the z-spectrum was interpolated to 1-Hz resolution with curve fitting. The minimum of the fitted z-spectra was assumed to be the water resonant frequency, which was shifted to 0 Hz (7). In addition, the two outermost points in the z-spectra were discarded due to the shifting (7). Two regions of interest (ROI) were then drawn manually. The first one covered the gray and white matter of the spinal cord, and the second one covered only the CSF. To minimize the partial volume effect, the ROIs were eroded for 1 voxel. Next, the homogeneity corrected z-spectral intensities (i.e. the interpolated and shifted raw data) at the corresponding positive and negative offsets around the water proton resonant frequency were compared on a voxel-by-voxel basis, in order to demonstrate the MTR asymmetry effect in the cervical spinal cord. The MTRasym was obtained for both gray/white matter and CSF in SE-EPI and GE-EPI sequences.

Statistical analysis

A one-sample Student’s t-test was performed on the mean MTRasym values from both SE-EPI and GE-EPI data. This examined whether there was any significant difference from zero at various frequency offsets for the detection of the conventional MT asymmetry and CEST effects in the gray/white matter and CSF. For the comparison between SE-EPI and GE-EPI data, a paired t-test was conducted to detect statistically significant difference at various frequency offsets. The P-value threshold used in all the t-tests (including the one-sample t-test and the paired t-test) was set at 0.05, two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons by Bonferroni correction.

Results

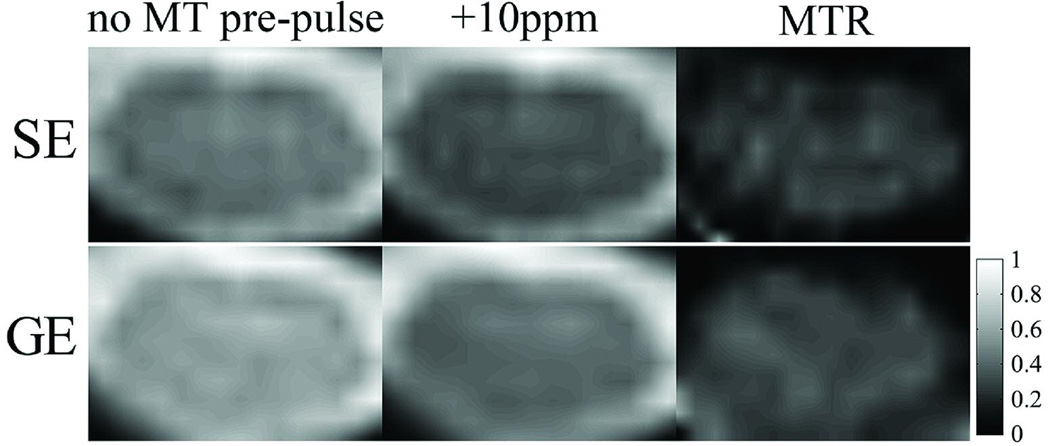

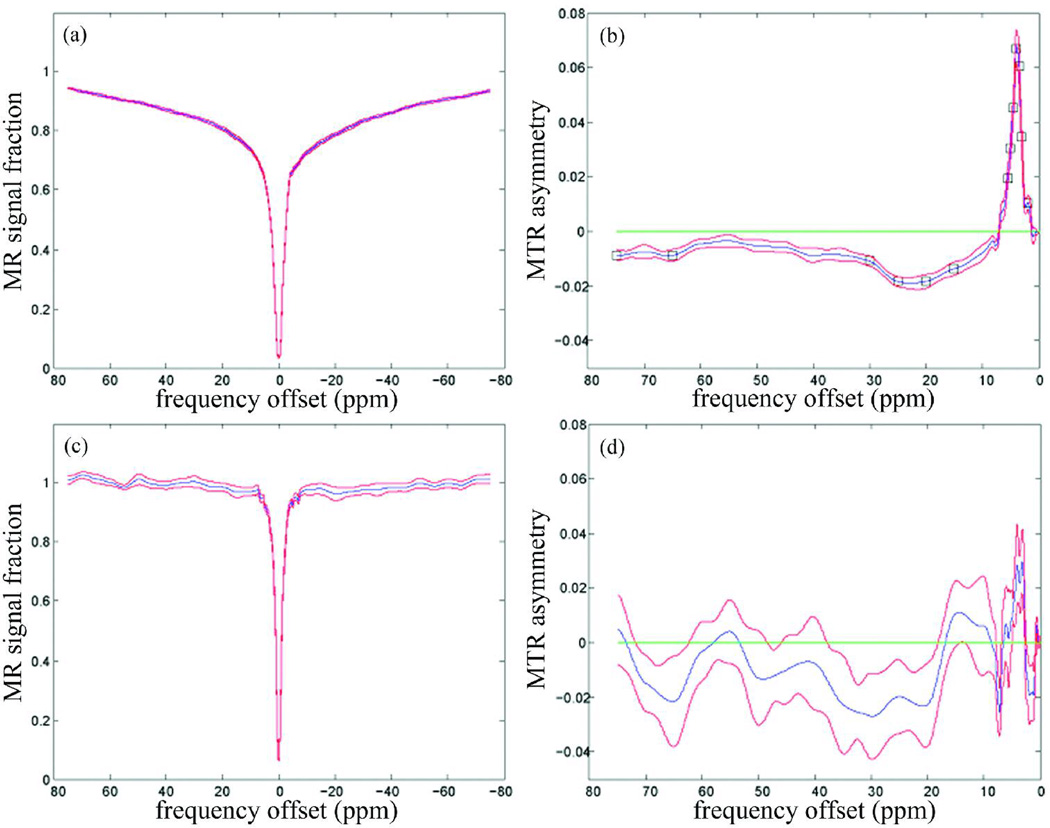

Figure 1 shows the representative SE-EPI and GE-EPI images with and without the MT pre-pulse, and the corresponding MTR images of the ones with MT pre-pulse. Figure 2 shows the z-spectra (fig. 2a, c) and the MTRasym spectra (fig. 2b, d) in the gray/white matter and CSF, averaged over 14 subjects from the SE-EPI data. Figure 3 shows the results from the GE-EPI data. The z-spectra in CSF (fig.2c and 3c) are narrower than in gray/white matter (fig.2a and 3a). In addition, the MR signal fraction Msat/M0 is near unity at off-resonance frequency offsets larger than 5ppm (fig.2c and 3c), while the gray/white matter has lower Msat/M0 (fig.2a and 3a). Furthermore, the statistical analysis from SE-EPI showed that the z-spectrum in the gray/white matter (fig. 2b) was asymmetrical about the water resonance frequency (P < 0.05). A larger saturation effect was observed on the negative offset side at the frequency offsets of 15 – 30ppm, 65ppm and 75ppm (minimum: −1.9% at 22.6ppm) and on the positive offset side at 2ppm, 3ppm and 3.5 – 5.5ppm (maximum: 6.8% at 3.9ppm). There was no significant difference of MTRs between corresponding negative and positive frequency offsets in CSF (fig. 2d).

Figure 1.

(left column) Representative spinal cord images from spin-echo (SE) and gradient-echo (GE) echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequences without MT pre-pulse; (middle column) SE-EPI and GE-EPI with MT pre-pulse at frequency offset +10ppm; (right column) corresponding magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) images of the middle column with color bar.

Figure 2.

Magnetization transfer (MT) asymmetry results from spin-echo echo-planar imaging (SE-EPI) data (n=14) (a) mean z-spectrum (blue line) with standard error of the mean (SEM; red line) of gray/white matter from C3/C4 - C5; (b) mean MTR asymmetry with SEM in gray/white matter. The black square on the curve highlights the points that the MTR asymmetry values at those particular frequency offsets are significantly different from zero by one-sample t-test (P < 0.05); (c) mean z-spectrum with SEM in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF); (d) mean MTR asymmetry with SEM in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

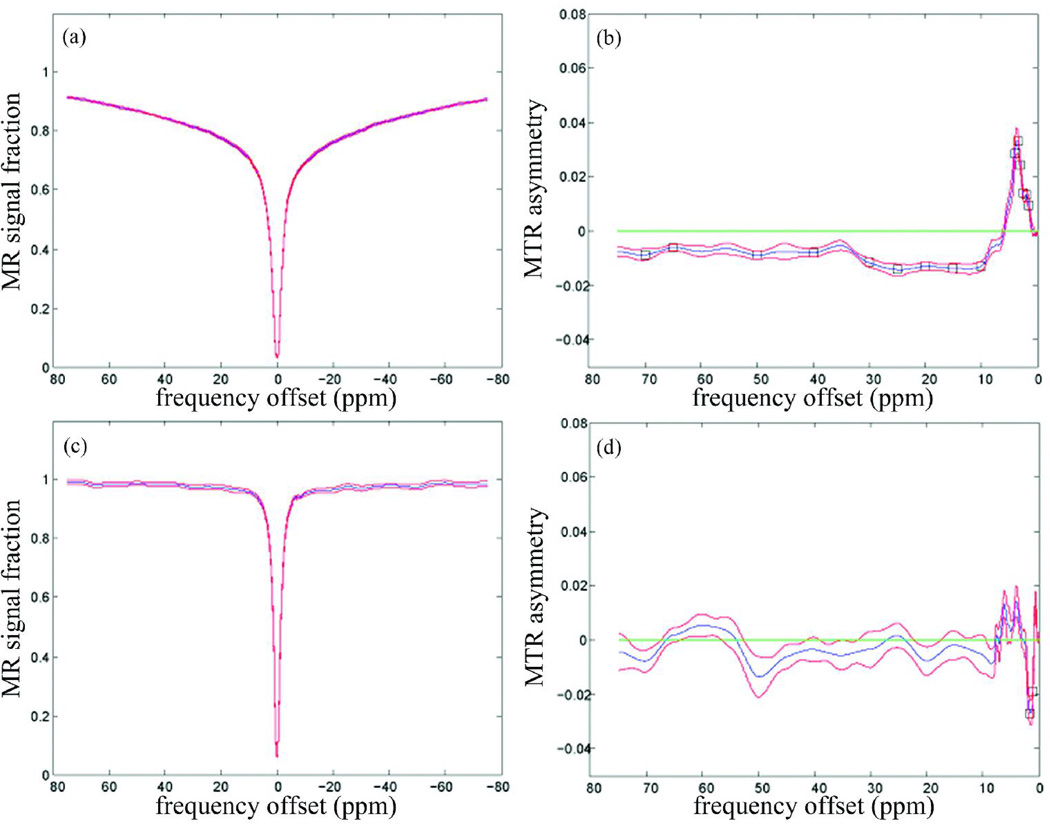

Figure 3.

Magnetization transfer (MT) asymmetry results from gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (GE-EPI) data (n=14): (a) mean z-spectrum (blue line) with standard error of the mean (SEM; red line) of gray/white matter from C3/C4 - C5; (b) mean MTR asymmetry with SEM in gray/white matter. The black square on the curve highlights the points that the MTR asymmetry values at those particular frequency offsets are significantly different from zero by one-sample t-test (P < 0.05); (c) mean z-spectrum with SEM in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF); (d) mean MTR asymmetry with SEM in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

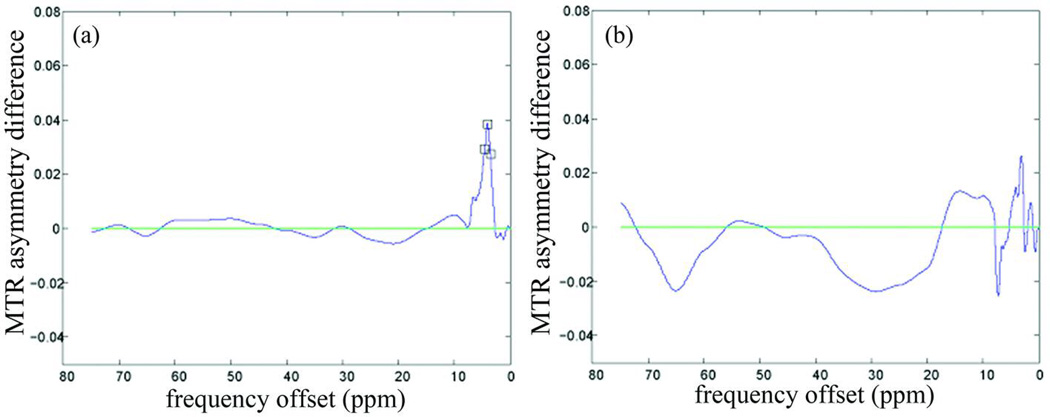

The GE-EPI data showed similar results as the SE-EPI data. The statistical analysis from GE-EPI showed that the z-spectrum in the gray/white matter (fig. 3b) was asymmetrical (P < 0.05). A larger saturation effect was similarly observed on the negative offset side at 10 – 30ppm, 40ppm, 50ppm, 65ppm and 70ppm (minimum: −1.4% at 24.5ppm) and on the positive offset side between 1.5 and 4ppm (maximum: 3.3% at 3.6ppm). The z-spectrum of CSF did not show any asymmetry around water resonance, except at frequency offsets of 1 and 1.5ppm (fig. 3d). Fig. 4 shows the difference of MTRasym values obtained in SE-EPI and GE-EPI sequences in gray/white matter and CSF respectively. The MTRasym values in gray/white matter obtained in SE-EPI were significantly higher than the ones in GE-EPI at frequency offsets between 3.5 and 4.5ppm (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Comparison of magnetization transfer ratio asymmetry (MTRasym) between spin-echo (SE) and gradient-echo (GE) echo-planar imaging (EPI) by paired t-test (SE minus GE): (a) in gray/white matter of the cervical spinal cord. (b) in cerebrospinal fluid. The black square on the curve shows that the MTRasym values obtained from SE and GE are significantly different at that particular frequency offset by paired t-test (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The current MT asymmetry study was carried out in the human cervical spinal cord at 3T using SE-EPI and GE-EPI with an MT pre-pulse. Our results demonstrated MTR asymmetry in the gray/white matter due to both conventional MT and CEST effects. The comparison of MTRasym between SE-EPI and GE-EPI further suggested that while both sequences had similar trends in the results, SE-EPI showed significantly higher MTR asymmetry than GE-EPI at the frequency range of the amide protons.

The gray/white matter mainly consists of axons, dendrites and cell bodies of the neural cells, which are composed of various proteins, peptides and macromolecules. Therefore, magnetization transfer effect exists through chemical exchange and cross-relaxation. On the other hand, CSF mainly consists of water. The concentration of proteins and amino acid in CSF is very low, so there is insignificant magnetization transfer. This explains the negligible MT effect in the CSF, which leads to a narrower z-spectrum when compared with the gray/white matter and the MR signal fraction Msat/M0 is driven to unity at off-resonance frequency offsets larger than 5ppm (fig. 2c and fig 3c). When comparing the MTRasym values between gray/white and CSF in SE-EPI (figures 2b,d) and GE-EPI (figures 3b,d), the z-spectrum in the gray/white matter was asymmetrical about the water resonance frequency, with more saturation effect at the lower frequencies (corresponding to a negative frequency offset) far away from water and at higher frequencies (a positive frequency offset) close to water. These results are consistent with the previous studies on the brain (7,8). The larger saturation effect at the negative offset frequencies far away from water was attributed to a center frequency shift from the semisolid pool with respect to water in conventional MT (7). The larger saturation effect at the positive offset frequencies close to water is more complicated. Both the conventional MT asymmetry and the CEST effect, e.g. the amide proton transfer (APT) effect at +3.5ppm (10), contribute to this effect. Our results demonstrated the MT asymmetry in the gray/white matter of human cervical spinal cord arising from both conventional MT and CEST effects. The CSF did not have a significant MT asymmetry at frequency offsets around 3.5ppm and >10ppm, as CSF had very little conventional MT and CEST effects. However, it is noted that the MTRasym value was significantly different from zero in CSF at frequencies very close to the water resonance (1ppm and 1.5ppm in fig. 3d) in GE-EPI. This may be due to the large standard deviation in MTRasym in CSF (18). In the literature, artifacts in CSF in APT-weighted images have been well documented (10,14,18).

In the comparison between GE and SE data, the paired t-test showed that SE has significantly higher MTRasym than GE in gray/white matter between 3.5ppm and 4.5ppm (fig. 4). This frequency range mainly corresponds to the amide protons. This suggests that the detecting sensitivity of the APT effect in the cervical spinal cord may be higher in the SE-EPI sequences. This can be explained by the fact that the cervical spinal cord is subjected to considerable magnetic field inhomogeneity because of the large susceptibility difference among the tissues. This problem can be minimized by using a spin-echo-based sequence. Due to the presence of the 180 degrees refocusing pulse, SE sequence can produce images with less intensity distortion, thus increasing the detecting sensitivity of MT asymmetry.

It has been shown that there exists a characteristic RF saturation power (ω1c) that maximizes the conventional MT asymmetry, and it approximately falls in the range of 0.5μT to 3.5μT at the frequency offsets of 5 – 60ppm (7). We therefore chose 2μT in this study mainly to keep the SAR at a reasonable level while achieving considerable amount of conventional MT asymmetry.

There are several limitations in our experiments. Firstly, the cross-sectional diameter of the spinal cord is very small (~10 mm), and single-shot EPI was used for fast imaging in the current study. Because of a long echo train length, EPI suffers from spatial blurring and susceptibility-induced distortion, especially in the cervical spinal cord (19,20). Also, due to the high sensitivity of MTR to motion (21), it is not easy to separate the gray and white matter to perform respective MT asymmetry analysis. Therefore, in this study, the gray and white matter was combined together. Secondly, physiological motion arising from blood, CSF flow and breathing can decrease the sensitivity of asymmetry detection. Therefore, VCG-triggering during data acquisition and image registration were used to reduce the physiological motion. Respiratory triggering was not used in this study, as a recent study in spinal fMRI suggested that motion from respiration is not a significant source of artifact (22).

The pre-phasing gradient lobe for phase-encoding in the default SE-EPI setting of our MR system is placed before the 180 degrees refocusing pulse. However, in the current study, it was moved to a position after the refocusing pulse. The advantage of this was to reduce the oblique flow displacement artifact (16) induced mainly from CSF. However, there was a disadvantage in doing so. The free-induction decay (FID) from the non-ideal refocusing pulse (flip angle ≠ 180 degrees) would also be phase-encoded, which might result in image artifacts (16). However, from our images, no significant artifact was observed in the spinal cord.

The significance of this study is that the existence of MT asymmetry in the human cervical spinal has been verified. The conventional MT asymmetry may give more insight into the interaction between semisolid tissue components and bulk water, providing a new MR contrast in certain pathology that affects the macromolecule pool or the chemical shift difference between the bulk water pool and the solid-like macromolecule pool (8). The CEST effect, more specifically APT, provides a method for detecting endogenous mobile proteins and peptides at a very low concentration through the water signal. It can be used to image tissue pH (10), tissue protein and peptide content (15). Moreover, the discovery of the MT asymmetry around the water resonance also necessitates more sophistication in some MRI experiments. For example, MT asymmetry adversely affects the accuracy of perfusion quantification in continuous-wave arterial spin labeling (CASL). Compensation schemes (23,24) such as gradient inversion (6), compensated δω2 inversion (6) and two-coil approach (24) have to be used. The conventional MT asymmetry will also complicate the quantification of CEST effect, as the two are concurrent. Proper algorithm has to be derived in order to separate the conventional MT asymmetry and CEST in the future.

In conclusion, magnetization transfer asymmetry has been demonstrated in gray/white matter of human cervical spinal cord at 3T. Both SE-EPI and GE-EPI showed consistent results. There was a larger saturation effect at the negative frequency offsets far away from water, which was attributed to a center frequency shift from the semisolid macromolecule pool with respect to water in conventional MT. Larger saturation effect was also observed at the positive offset frequencies close to water, which was attributed mainly to a type of CEST effect, the amide proton transfer (APT) effect. Results obtained using a SE sequence showed significantly higher MTRaysm than GE at the amide proton frequency range, possibly due to less intensity distortion in SE.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge 3T MRI Unit, The University of Hong Kong for support in the usage of the scanner. We would also like to thank Mr. Tsz-Kit Cheung, Mr. Ting-Hung Li and Mr. Li Hu for their help in the preparation of the experiment.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have reported no conflicts of interest. The results have been accepted as a poster presentation in the coming 16th ISMRM conference, Toronto, May 2008 and will be published as an abstract in the conference proceedings (in press).

References

- 1.Wolff SD, Balaban RS. Magnetization transfer contrast (MTC) and tissue water proton relaxation in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 1989;10:135–144. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910100113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balaban RS, Ceckler TL. Magnetization transfer contrast in magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Q. 1992;8:116–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryant RG. The dynamics of water-protein interactions. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1996;25:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.25.060196.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henkelman RM, Stanisz GJ, Graham SJ. Magnetization transfer in MRI: a review. NMR Biomed. 2001;14:57–64. doi: 10.1002/nbm.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henkelman RM, Huang X, Xiang QS, Stanisz GJ, Swanson SD, Bronskill MJ. Quantitative interpretation of magnetization transfer. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29:759–766. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pekar J, Jezzard P, Roberts DA, Leigh JS, Jr, Frank JA, McLaughlin AC. Perfusion imaging with compensation for asymmetric magnetization transfer effects. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:70–79. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hua J, Jones CK, Blakeley J, Smith SA, van Zijl PC, Zhou J. Quantitative description of the asymmetry in magnetization transfer effects around the water resonance in the human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:786–793. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hua J, van Zijl PC, Sun PZ, Zhou J. Quantitative Description of Magnetization Transfer (MT) Asymmetry in Experimental Brain Tumors; Proc 15th ISMRM; Berlin, Germany. 2007. (Abstract 882) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein AD, Roberts DA, McGowan J, Reddy R, Leigh JS. Asymmetric cancellation of magnetization transfer effects; The 2nd Annual Meeting of SMR; San Francisco, CA. 1994. (Abstract 880) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou J, Payen JF, Wilson DA, Traystman RJ, van Zijl PC. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nat Med. 2003;9:1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolff SD, Balaban RS. NMR imaging of labile proton exchange. J Magn Reson. 1990;86:164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guivel-Scharen V, Sinnwell T, Wolff SD, Balaban RS. Detection of proton chemical exchange between metabolites and water in biological tissues. J Magn Reson. 1998;133:36–45. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) J Magn Reson. 2000;143:79–87. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging and spectroscopy. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 2006;48:109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou J, Lal B, Wilson DA, Laterra J, van Zijl PC. Amide proton transfer (APT) contrast for imaging of brain tumors. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:1120–1126. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernstein MA, King KF, Zhou XJ. Handbook of MRI pulse sequences. Boston: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. p. 1017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woods RP, Grafton ST, Watson JD, Sicotte NL, Mazziotta JC. Automated image registration: II. intersubject validation of linear and nonlinear models. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 1998;22:153–165. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199801000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou J, Wilson DA, Sun PZ, Klaus JA, Van Zijl PC. Quantitative description of proton exchange processes between water and endogenous and exogenous agents for WEX, CEST, and APT experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:945–952. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng MC, Smith SA, Gillen JS, et al. Improved distortion correction in cerebral and spinal DTI using interleaved reversed gradients; Proc ISMRM-ESMRMB; Berlin, Germany. 2007. (Abstract 2124) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voss HU, Watts R, Ulug AM, Ballon D. Fiber tracking in the cervical spine and inferior brain regions with reversed gradient diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith SA, Golay X, Fatemi A, et al. Magnetization transfer weighted imaging in the upper cervical spinal cord using cerebrospinal fluid as intersubject normalization reference (MTCSF imaging) Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:201–206. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stroman PW. Discrimination of errors from neuronal activity in functional MRI of the human spinal cord by means of general linear model analysis. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:452–456. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pekar J, Jezzard P, Roberts DA, et al. Perfusion imaging with MTC offset compensation; 2nd Annual Meeting of SMR; San Francisco, CA. 1994. (Abstract 281) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Detre JA, Zhang W, Roberts DA, et al. Tissue specific perfusion imaging using arterial spin labeling. NMR Biomed. 1994;7:75–82. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940070112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]