Abstract

Patient: Female, 43

Final Diagnosis: Fahr disease

Symptoms: Movement disorder • chorea and tremors • cognitive deficit • behavioral aggressiveness and restlessness • visual hallucination

Medication: Haloperidolo • levomepromazine • sodium valproate

Clinical Procedure: Neurology examination • neuropsychological examination • MRI

Specialty: Neurology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Fahr’s disease (FD), or primitive idiopathic calcification of the basal ganglia, is a rare neurodegenerative syndrome characterized by the presence of idiopathic bilateral and symmetrical cerebral calcifications.

Case Report:

We describe the case of 43-year-old woman presenting with psychiatric symptoms, disorganized behavior, and migraine. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination showed basal ganglia calcifications. In addition, we analyzed the cortical brain volume and noted cortical atrophy. Extensive etiological clinico-biological assessment allowed us to exclude known causes of brain calcifications and to diagnose Fahr disease (FD). Neurological symptoms associated with psychiatric manifestations are not uncommon in FD.

Conclusions:

Purely psychiatric presentations are possible, as demonstrated by the present case, although there have been very few cases reported. To date, no studies related to the brain atrophy in FD have been reported.

MeSH Keywords: Basal Ganglia, Psychiatry, Thalamus

Background

Fahr’s disease (FD) or primitive idiopathic calcification of the basal ganglia, is a rare neurodegenerative syndrome characterized by the presence of idiopathic bilateral and symmetrical cerebral calcifications in globus pallidus, putamen, caudate nucleus, dentate nucleus, and lateral thalamus (striopallidodentate calcification) and in cerebral cortex, internal capsule, and cerebellar areas [1]. The prevalence of FD is not known, but it is very rare and it is more common in men (male: female ratio 2:1). FD is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait, but autosomal recessive inheritance patterns have been proposed. A locus at 14q has been suggested to be commonly involved in the genetic transmission of FD [2].

The etiology of the sporadic form is not known; in fact, different agents could be implicated. The most common symptoms are related to endocrine disorders, mitochondrial myopathies, dermatological, and infectious diseases [3]. Furthermore, a clinical condition similar to FD can be found in hypoparathyroidism with hypocalcaemia and calcification of the basal ganglia.

Patients with FD show a slowly progressive movement disorder and extrapyramidal symptoms characterized by dystonia, poor balance and bradykinesia, ataxia, headache, seizures, vertigo, tremor, dysarthria, and paresis [4]. FD appears most commonly with motor deficits; however, some patients initially present psychiatric symptoms such as depression, hallucinations, delusions, manic symptoms, anxiety, schizophrenia-like psychosis, personality change, and psychosis [5]. Indeed, more extensive calcification is known to correlate with the presence of psychiatric manifestations, progressive memory disorder, cognitive impairment, and dementia. In addition, no data have correlated cognitive and motor impairment with brain atrophy.

Case Report

We report the case of a 43-year-old woman experiencing migraine without aura or anxiety disorder since adolescence. In 2004, at age 33, she was hospitalized for headache and episodes of loss of consciousness. A second hospitalization, due to painful symptoms caused by migraine, deflection of mood, and mental confusion, occurred in 2006. In 2013, the patient was hospitalized after an episode of verbal and behavioral aggressiveness and restlessness, visual hallucination, and mental confusion. A brain computed tomography (CT) scan showed multiple bilateral calcifications in the corona radiata, as well as lentiform and dentate nuclei and thalamus; other millimetric calcifications were highlighted in the caudate nucleus, pons and in the right occipital cortex. Electroencephalography (EEG) appeared severely altered to the almost complete absence of normal rhythms and slow theta-delta activity, showing the presence of epileptiform activity characterized by short episodes of bilaterally synchronous and symmetric wave functions. Hematological and biochemical parameters were within normal range. She was diagnosed with sporadic FD.

The patient came to our observation, in 2014, for the highly disabling symptoms caused by migraine and behavioral disorders, anxiety, irritability and aggressiveness. She suffered from insomnia. She had no history of infectious disease, exposure to toxic substances, or other significant traumatic events in her life. Neuropsychological examination showed a cognitive decline in multiple domains such as executive skills, visual-spatial ability, attention, and memory. Low scores on the sub-scale test of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS.2 percentile) were recorded [6]. In addition, a global cognitive assessment was obtained with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which showed mild cognitive impairment (22/30). [7]. We also administered the Trail Making Test A and B to examine attention/executive function [8]. The results showed a significant performance deficit: TMA score was 206.26 (cut-off 93) and TMB score was 712 (cut-off 282).

The neurological examination showed dysarthria, mild tremor, and gait impairment. Biochemical and somatic features did not suggest a metabolic disease or other systemic disorder. Her symptoms fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of FD. Haloperidol, levomepromazine, and sodium valproate were used in the management of behavioral problems, with poor compliance.

The patient and 5 sex- and age-matched normal controls (NC) underwent a conventional and quantitative brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on a system operating at 3.0 T (Achieva Philips, the Netherland) using a 32-channel SENSE head coil.

A T1-weighted 3D fast-field echo (FFE) sequence, a dual-echo, turbo spin-echo sequence, and FLAIR images were acquired. All cerebral volumes (normalized brain volume [NBV] and normalized cortical volume [NCV]) were measured on T1W 3D images by using the cross-sectional version of SIENA (structural image evaluation using normalization of brain atrophy) software, SIENAX (part of FSL 5.0: http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/), a tool used to estimate the global brain volume normalized for head size.

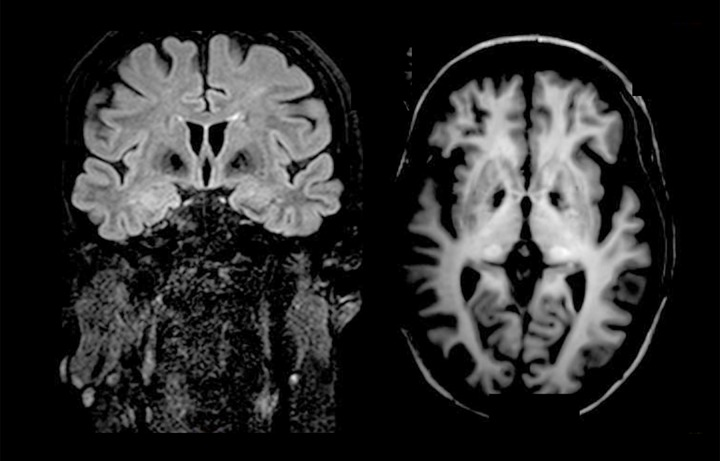

MRI examination showed millimetric hyperintense lesions in the peritrigonal white matter area and in semioval centers. T1-weighetd and FLAIR images showed bilateral hypointense signal intensity of the globus pallidus and bilateral hyperintensity in the thalamus, caused by calcium deposits (Figure1). The NBV was 1477.9 mm3 for the patient and 1523.8±22.5 mm3 for the NC (p<0.01), and the NCV was 499.0 mm3 for the patient and 542.0±23.5 mm3 for the NC (p<0.01).

Figure 1.

Coronal FLAIR and axial T1- weighted images showed calcification at the basal ganglia.

Discussion

About 40% of patients with FD initially present psychiatric symptoms [9]. Two patterns of psychotic presentation in Fahr’s disease are known, including early onset (mean age 30.7 years) with minimal movement disorder, and late onset (mean age 49.4 years) associated with dementia and movement disorders [10]. Psychotic symptoms in Fahr’s disease include auditory and visual hallucinations, perceptual distortions, delusions, and fugue state. Our patient showed some of these symptoms. At onset, she presented symptoms characterized by psychosis, confusional episodes, migraine, and no extra-pyramidal involvement. Subsequently, however, the psychiatric symptomatology was associated with progressive cognitive impairment and motor disorders. Our patient showed, in fact, a complex symptomatology caused by calcification of the basal ganglia and thalamus, as demonstrated by MRI. The neuropsychological results showed impairment in sustained and divided attention, working memory, word fluency, speed of information processing, mental flexibility, memory, new learning, and problem solving. The patient also presented dysarthria, (difficulty in articulating sounds) due to the inability to coordinate motor functions. Indeed, it is known that brain injury, especially injury involving the coordination of movements, maintenance of motor rhythm, and muscle tone in the basal ganglia region, damages oral expressiveness and impedes ability to speech.

The basal ganglia have been considered to be primarily involved in the control of motor functions, but they are also involved in numerous cognitive processes based to their connections with the frontal cortex [11]. Basal ganglia and thalamic regions are involved in various aspects of motivation, emotional drive, planning, and cognition for the development and expression of goal-directed behaviors and motor control through cortico-basal and cortico-thalamic circuits and the connections between specific areas of the frontal cortex [12]. Psychiatric symptoms in FD could be caused by abnormalities in the basal ganglia, which are central to the pathophysiology of psychiatric conditions, and by interruption of the dorsolateral prefrontal circuit involving the thalamus. In addition, the modifications in this cortical area, rich in dopaminergic innervation, could explain the alteration of visual perception [13]. Structural abnormalities in the basal ganglia and thalamus have also been observed in psychosis [14]. We showed MR structural abnormalities as bilateral hypointense signal intensity of the globus pallidus and bilateral hyperintensity in the thalamus caused by calcium deposits [15,16]. We also showed that the cortical volume of a patient is significantly reduced when compared to the NC. To date, no data are available on the possible role of brain cortical volume in psychiatric symptoms and cognitive impairment in FD. In addition, we used an automatic tool, SIENA [17], to quantify decreased normalized brain volume and decreased normalized cortical volume, not just global brain volume changes, as previous studies reported [18,19].

Therefore, we suggest that the cortical areas are involved in the pathogenesis of behavioral symptoms in FD, as in other neurological diseases. However, it is very difficult to prove this because this report is limited to only a single case.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we describe a case of psychiatric presentation of FD, associated with cognitive impairment and, for the first time, to cortical brain atrophy, measured automatically and not manually, in an operator-dependent visual examination. FD is poorly studied, and case series and cohort studies are necessary to better describe the neurological and psychiatric signs associated with this heterogeneous disease. The ongoing progress in determining the genetic bases of this syndrome implies that clinicians need to improve their description of clinical, psychological, and quantitative cortical MRI markers. In fact, cortical brain atrophy could be implicated in the onset of psychiatric and cognitive symptoms.

References:

- 1.Manyam BV. What is and what is not “Fahr’s disease”. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005;11:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manyam BV. Bilateral striopallidodentate calcinosis: a proposed classification of genetic and secondary causes. Mov Disord. 1990;5(Suppl.1):94. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asokan AG, D’souza S, Jeganathan J, Pai S. Fahr’s syndrome-an interesting case presentation. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(3):532–33. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/4946.2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mufaddel AA, Al-Hassani GA. Familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification (Fahr's disease) Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2014;19(3):171–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Everitt BJ, Parkinson JA, Olmstead MC, et al. Associative processes in addiction and reward. The role of amygdala-ventral striatal subsystems. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;877:412–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. Repeatable Battery for Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinic validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20:310–19. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician”. J Psychiatric Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reitan R. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–76. [Google Scholar]

- 9.König P. Psychopathological alterations in cases of symmetrical basal ganglia sclerosis. Biol Psychiatry. 1989;25:459–68. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings JL, Gosenfeld LF, Houlihan JP, McCaffrey T. Neuropsychiatric disturbances associated with idiopathic calcification of the basal ganglia. Biol Psychiatry. 1983;18:591–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shatner M, Havazelet-Heimer G, Raz A, Bergman H. In: Cognitive decision processes and functional characteristics of the basal ganglia reward system. 52. Kitai S, DeLong M, Graybiel A, editors. Vol. 12. The Basal Ganglia VI, Plenum Press; New York: 2002. pp. 303–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haber SN, Calzavara R. The cortico-basal ganglia integrative network: The role of the thalamus. Brain Res Bull. 2009;78(2–3):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howes OD, Kapur S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Version III – The final common pathway. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(3):549–62. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandt GN, Bonelli RM. Structural neuroimaging of the basal ganglia in schizophrenic patients: a review. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2008;158:84–90. doi: 10.1007/s10354-007-0478-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehto LJ, Sierra A, Corum CA, et al. Detection of calcifications in vivo and ex vivo after brain injury in rat using SWIFT. Neuroimage. 2012;61(4):761–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bekiesinska-Figatowska M, Mierzewska H, Jurkiewicz E. Basal ganglia lesions in children and adults. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82(5):837–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith SM, Zhang Y, Jenkinson M, et al. Accurate, robust, and automated longitudinal and cross-sectional brain change analysis. Neuroimage. 2002;17(1):479–89. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Modrego PJ, Mojonero J, Serrano M, Fayed N. Fahr’s syndrome presenting with pure and progressive presenile dementia. Neurol Sci. 2005;26:367–69. doi: 10.1007/s10072-005-0493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Hechmi S, Bouhlel S, Melki W, El Hechmi Z. Psychotic disorder induced by Fahr’s syndrome: a case report. Encephale. 2014;40(3):271–75. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]