Abstract

Recently, a small subset of T cells that expresses the B cell marker CD20 has been identified in healthy volunteers and in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. The origin of these CD20-positive T cells as well as their relevance in human disease remains unclear. Here, we identified that after functional B cell/T cell interaction CD20 molecules are transferred to the cell surface of T cells by trogocytosis together with the established trogocytosis marker HLA-DR. Further, the presence of CD20 on isolated CD20+ T cells remained stable for up to 48h of ex vivo culture. These CD20+ T cells almost exclusively produced IFNγ (∼70% vs. ∼20% in the CD20− T cell population) and were predominantly (CD8+) effector memory T cells (∼60–70%). This IFNγ producing and effector memory phenotype was also determined for CD20+ T cells as detected in the peripheral blood and ascitic fluids of ovarian cancer (OC) patients. In the latter, the percentage of CD20+ T cells was further strongly increased (from ∼6% in peripheral blood to 23% in ascitic fluid). Taken together, the data presented here indicate that CD20 is transferred to T cells upon intimate T cell/B cell interaction. Further, CD20+ T cells are of memory and IFNγ producing phenotype and are present in increased amounts in ascitic fluid of OC patients.

Keywords: Ascites, cancer immunology, CD20, ovarian cancer, trogocytosis

Abbreviations: APC, Antigen-Presenting Cell; CTL, Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte; FSC, Forward Scatter; OC, Ovarian Cancer; PBMC, Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell; SCC, Side Scatter; TC, Cytotoxic T cell; TCM, Central Memory T cell; TEM, Effector Memory T cell; TH, Helper T cell; TIL, Tumor Infiltrating T cell; TNaïve, Naïve T cell; Treg; Regulatory T cell; TTD, Terminally Differentiated T cell

Introduction

OC remains the most deadly gynecological malignancy with a 5-y survival rate of only 45%.1,2 This poor prognosis is largely due to therapy-resistant relapses that occur in the majority of patients following first line therapy.3,4 Interestingly, a subset of patients appears to remain disease-free for prolonged periods of time. To date, several factors have been identified that can be used to define this particular subset of patients with arguably the strongest prognostic indicator being early detection and treatment.3,4 In addition, studies by us and others have revealed strong links between antitumor immune responses and patient survival.5–8 Specifically, the presence of CD3+ and CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) and their relative abundance versus regulatory T cells (Treg) is strongly associated with better survival.7

In addition to Tumor-infiltrating T cells, it was recently shown that tumor-infiltrating CD20+ B cells (CD20+ TIL) are strongly associated with improved patient survival in high grade serous OC.9 Of note, these CD20+ B-cells were found to strongly co-localize with CD8+ cytolytic T-cells (CTLs), suggesting that these cells may work cooperatively to mediate antitumor immunity in OC.10 In this respect, it is worth noting that B cells can serve as antigen-presenting cells (APC) to T cells (reviewed in ref. 11). Indeed, under specific circumstances B-cel APCs can be more effective at antigen presentation than dendritic cells and may thus contribute to anti-OC immunity by providing local antigen presentation to T cells.12

Indirect evidence for such antigen presentation of B to T cells in ovarian carcinoma might be obtained by evaluating intercellular exchange of membrane components between these two cell types, as several groups have recently demonstrated that antigen-loaded MHC class II molecules, specifically HLA-DR, can be transferred between various cells of the immune system during antigen presentation by a process known as trogocytosis.13 During trogocytosis, intact proteins, protein complexes and/or even membrane patches are transferred from one cell type to the other.14–17 In addition to HLA-DR transfer, other accessory molecules involved in this contact were found to be similarly transferred.18 Interestingly, we and others have recently demonstrated the presence of a small population of T-cells that express the B-cell marker CD20 in the peripheral blood of healthy volunteers and patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis.19,20 Based on this “hybrid” phenotype, we speculated that these cells might have acquired B cell membrane molecules during intercellular contact with B cells. Therefore, we here set out to determine whether CD20+ T cells could originate as a result of B cell/T cell interaction and whether this population was present in patients with OC, in particular in peripheral blood and in inflammatory ascites fluid.

Results

T cells acquire CD20 by trogocytosis and maintain a stable CD20-positive phenotype up to 48 h after isolation

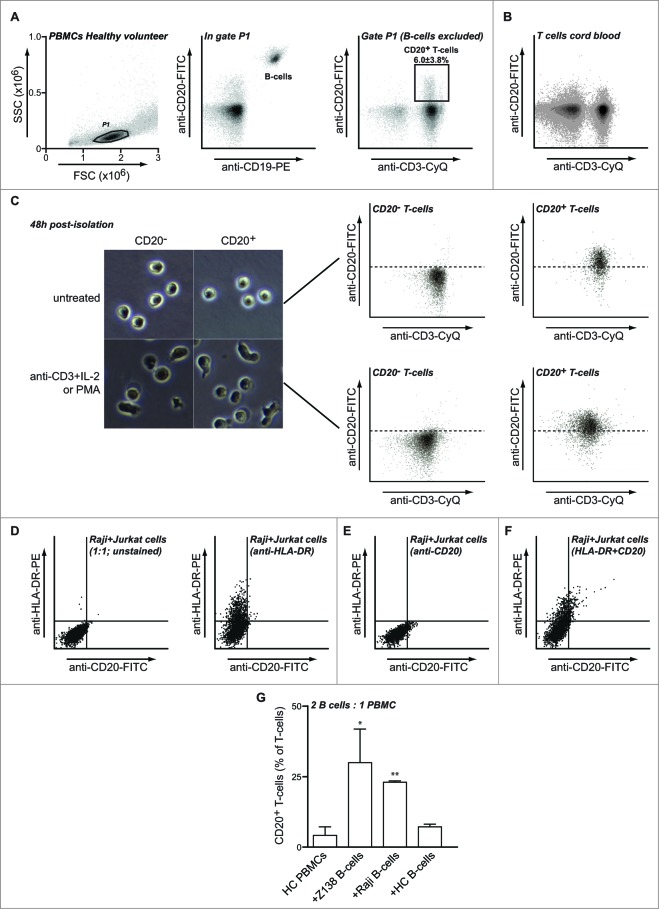

Previous studies by us and others identified a subset of T cells that expressed the typical B cell marker CD20.19,20 The origin of such CD20+ T cells remains unclear, but they may arise as a result of intercellular membrane exchange during intimate T cell / B cell interaction. In line with this, a CD19− CD3+ CD20dim population of T-cells could be clearly identified (Fig. 1A and S1A). In a panel of 10 healthy volunteers, this CD20+ T-cell population comprised 6.0 ± 3.8% of the total T cell population (Fig. 1A). Importantly, the anti-CD20 antibody Rituximab fully specifically blocked CD20 on T cells as well as on B cells, confirming the specificity of the anti-CD20 antibody we used in identifying the T-cell subpopulation (Fig. S1B). Of note, in CD3+ T-cells isolated from cord blood this T-cell population was largely absent (Fig. 1B), which suggests that CD20+ cells may possibly arise later in life due to T cell / B cell interaction. Of note, presence of CD20 on the cell surface of CD20+ T cell population in the peripheral blood of adult healthy volunteers was stable, with CD20 presence being retained for up to 48 h of culture of isolated CD20+ T cells (Fig. 1C). Reversely, the sorted CD20− T-cell population remained CD20-negative during this time (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

T cells can acquire CD20 upon co-culture with B cells. (A–B) Peripheral blood of healthy volunteers (A) or cord blood (B) was stained using anti-CD3-CyQ, anti-CD19-PE, and anti-CD20-FITC. Plots represent cells gated on FSC/SSC followed by exclusion of B-cells based on co-expression of CD19 and CD20. (C)PBMCs from healthy volunteers were stained using anti-CD3-CyQ, anti-CD19-PE and anti-CD20-FITC and CD20− and CD20+ T cell populations isolated using multicolor cell sorting. Isolated cells were left untreated or activated using a cocktail of anti-CD3 mAb and IL-2 for 48 h after which cells were examined for CD3 and CD20 expression. (D-F) Jurkat T cells were co-cultured with CD20+ B cell line Raji for 15 min and expression of HLA-DR (D), CD20 (E) or both (F) was assessed by flow cytometry on gated CD3+ T-cells. (G) PBMCs of healthy volunteers were incubated alone or in the presence of Z138, Raji or healthy control B cells at a ratio of 2–1 for 1h followed by flow cytometric analysis for CD20 expression within the CD3+ population. Asterisks represent significant changes compared to PBMCs alone.

To determine whether transfer of CD20 from B cells to T cells could occur by trogocytosis, Jurkat leukemic T-cells were subsequently mixed with the B cell line Raji. In line with earlier studies, this co-incubation triggered the rapid transfer of surface HLA-DR to Jurkat T-cells within 15 min (Fig. 1D) 13. Within the same time-frame, CD20 was similarly transferred to Jurkat cells albeit to a lesser extent (Fig. 1E). Of note, on these Jurkat cells the presence of CD20 was found concurrent with acquisition of HLA-DR (Fig. 1F). In control monocultures, Jurkat cells did not acquire CD20 or HLA-DR (data not shown). Thus, CD20 can be transferred from B-cells to leukemic T-cells in a time-frame of minutes.

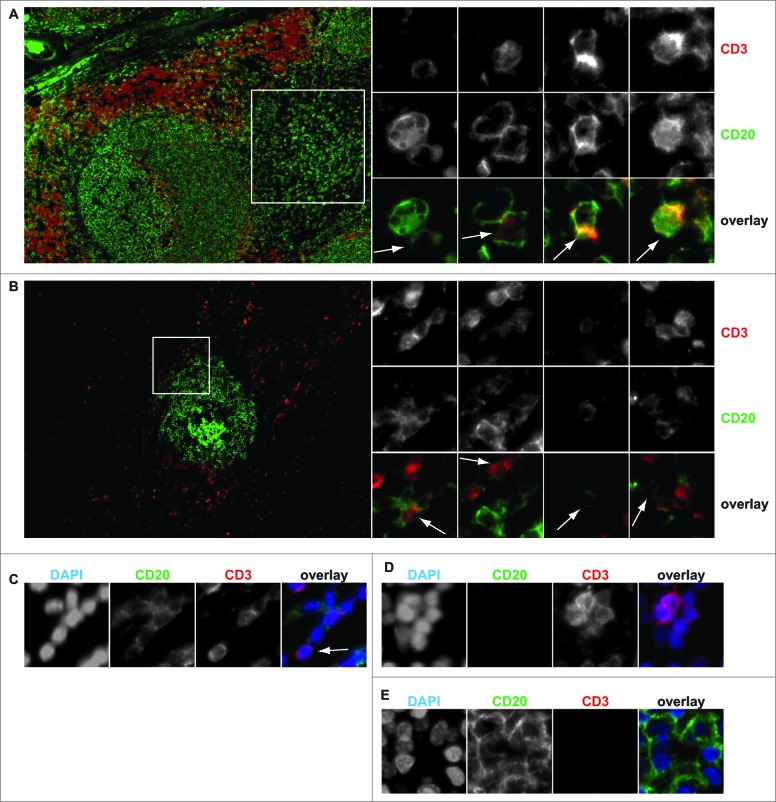

To further evaluate this possible mechanism for peripheral blood T-cells, PBMCs from healthy volunteers were isolated and mixed with the B cell line Z138, a cell line that expresses high levels of CD20. After 1h co-culture of PBMCs with Z138, the percentage of primary T cells that expressed CD20 increased from ∼4% to ∼30% (Fig. 1G). Similar co-incubation with B-cell Raji also induced transfer of CD20 to primary T-cells (Fig. 1G, 4% vs. 24%). Co-incubation of primary T-cells with primary HLA-mismatched B cells was associated with a reproducible increase of ∼3% CD20+ T cells (Fig. 1G). As reported previously for B cells,15 trogocytosis was significantly reduced but still occurred when cells were co-cultured for 1h on ice (not shown). Finally, a small number of CD3+ T cells were found to co-express CD20 both in the human tonsil and in lymphoid-like structures in ovarian tumors (Fig. 2A and B, respectively). These CD20+ T-cells were single cells (Fig. 2C) and had the typical size of T-cells (Fig. 2D), with B-cells being significantly larger (Fig. 2E). CD20+ T-cells were always found in close proximity to B cells and several B cell : T cell pairs displayed an intimate membrane interaction (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

In situ identification of CD3+ CD20+ T-cells. (A)Tonsil and (B)ovarian tumor tissue was stained for CD3 and CD20 and co-expression assessed by multicolor immunofluorescent microscopy. Insets identify the region where individual CD3+ CD20+ T cells could be identified. (C)single cell expression of CD3 and CD20 was validated using counterstaining with DAPI. (D)CD20− CD3+ T-cells and (E)CD20+ CD3− B cells could also be readily identified.

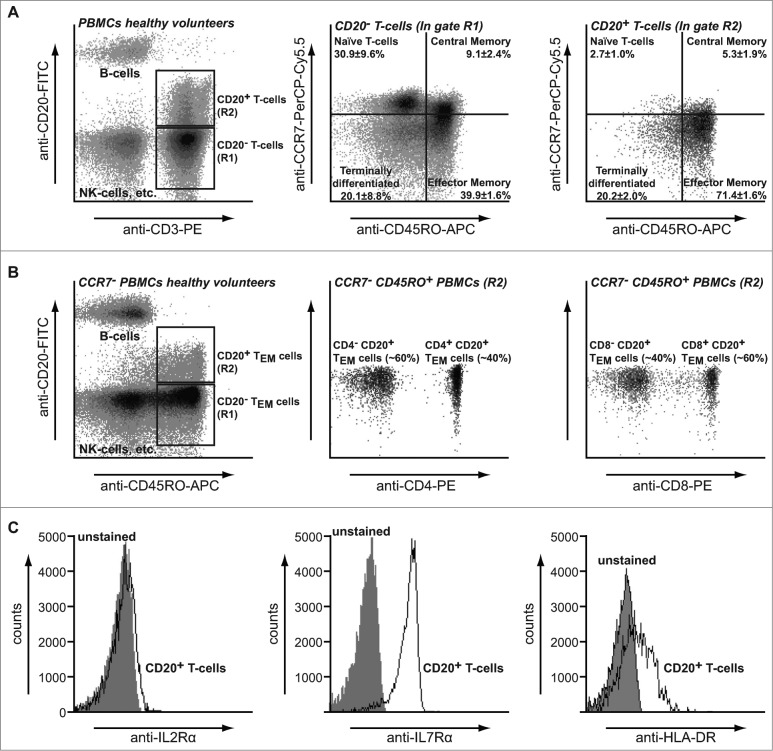

CD20+ T cells are HLA-DR+ and CCR7−/CD45RO+ effector memory T cells in healthy volunteers and ovarian cancer (OC) patients

The above data indicate that T-cells acquire CD20 molecules after B/T cell interaction, which suggests that CD20 should predominantly be found on memory T-cells. Therefore, the phenotype of circulating CD20+ T cells in peripheral blood from healthy volunteers and OC patients was further determined. CD20 within the T cell population was almost exclusively detected on effector memory T cells (TEM) in both healthy volunteers and OC patients (Fig. 3A; 71.4 ± 1.6% and Fig. 5A; 63.2 ± 9.0%), as well as on terminally differentiated T cells (TTD, Fig. 3A; 20.2 ± 2.0% and Fig. 5A; 29.7 ± 8.2%). Within this CD20+ TEM population, expression was skewed toward CD8+ cells over CD4+ cells (Fig. 3B; 60% vs. 40%). In contrast, CD20− T cells displayed a distribution typically found in peripheral blood with naïve (30.9±9.6%), central memory (TCM; 9.1 ± 2.4%), effector memory (TEM; 39.9 ± 1.6%) and terminally differentiated T-cells (TTD; 20.1 ± 8.8%). Furthermore, CD20− T cells contained a higher percentage of CD4+ T-cells than CD8+ T-cells (Figure S1C; 40% vs. 60%). Interestingly, CD20+ but not CD20− T-cells also expressed HLA-DR on their cell surface (Fig. 3C and S1D), consistent with the possible acquisition of cell membrane from APCs. Both CD20+ and CD20− T cells expressed CD127 (IL-7R), but not CD25 (IL-2R) (Fig. 3C and S1D).

Figure 3.

Phenotype of CD20+ T-cells. (A)PBMCs from healthy volunteers were stained using anti-CD3-CyQ, anti-CD19-PE and anti-CD20-FITC and prevalence of T cell subpopulations assessed using flow cytometry. PBMCs were strictly gated on FSC/SSC to exclude B/T doublets (left panel) and B cells excluded from analysis after identification based on co-expression of CD19 and CD20 (middle panel). (B)PBMCs from healthy volunteers were stained using anti-CD3-PE, anti-CD20-FITC, anti-CD45RO-APC and anti-CCR7-PerCP-Cy5.5 mAbs and analyzed using flow cytometry. (C)PBMCs from healthy volunteers were stained using anti-CD20-FITC, anti-CD45RO-APC and anti-CCR7-PerCP-Cy5.5 (left panel) in combination with either anti-CD4-PE (middle panel) or anti-CD8-PE (right panel) mAbs and analyzed using flow cytometry. Middle and right panels are gated on the CD20+ T cells. (D)CD20+ T cells identified as described in A were further characterized for expression of CD25 (left panel), CD127 (middle panel) or HLA-DR (right panel) using flow cytometry. Percentages ± SD are representative of seven healthy donors.

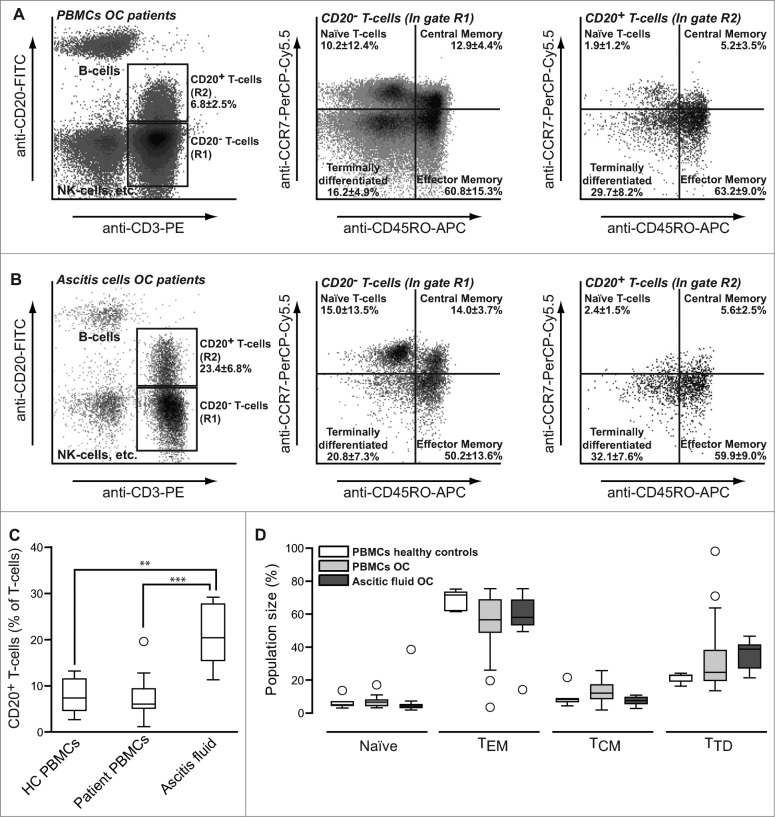

Figure 5.

Prevalence and subtype of CD20+ T-cells in patients with ovarian cancer. PBMCs (A) or ascites fluid cells (B) from patients with ovarian cancer were stained using anti-CD3-PE, anti-CD20-FITC, anti-CD45RO-APC and anti-CCR7-PerCP-Cy5.5 mAbs and analyzed using flow cytometry. (C-D) Percentages (C) and subset distribution (D) of CD20+ T cells in peripheral blood of healthy volunteers, peripheral blood of patients with ovarian cancer and in ascites fluid of ovarian cancer. Data were analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

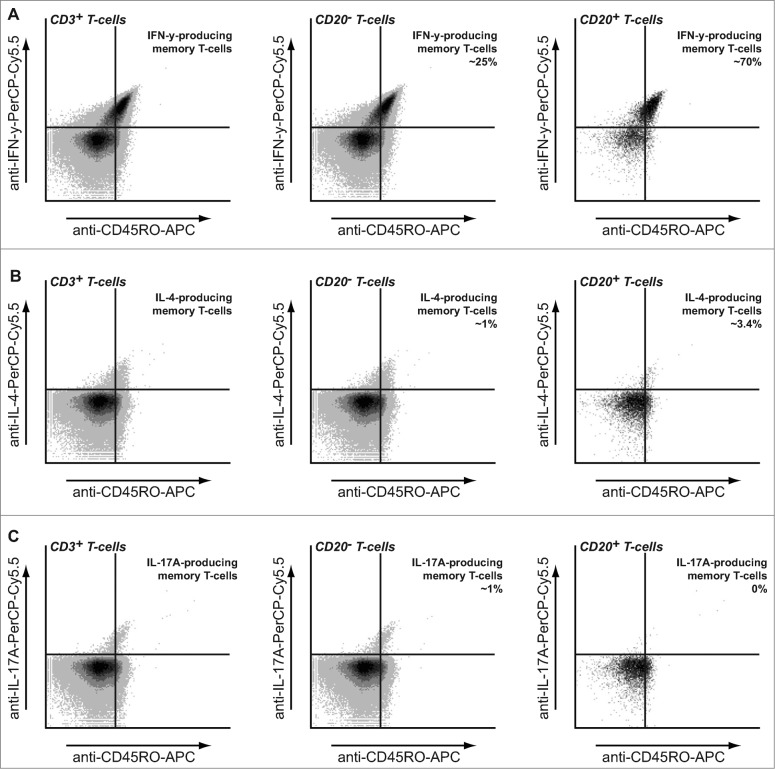

CD20+ T cells are IFNγ producing TH1/TC1 cells in healthy volunteers and OC patients

To further characterize the CD20+ T cell population, intracellular cytokine stainings were performed to identify TH1/TC1, TH2/TC2 or TH17 cells. CD3+ PBMCs were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin in the presence of Brefeldin A and intracellular cytokine staining performed in conjunction with CD19, CD20, and CD45RO. As anticipated, non-gated CD3+ T cells as well as the CD20− T-cell population contained both IFNγ (Fig. 4A), IL-4, (Fig. 4B) and IL-17 (Fig. 4C) producing cells, with CD45RO+ memory T cells being largely responsible for cytokine secretion (Fig. 4A–C; left panels). However, within the CD20+ T cell population, that consisted of >95% CD45RO+ memory T-cells, almost all cells produced IFNγ, with only a small percentage of cells that produced IL-4 and no IL-17 production (Fig. 4A–C). These findings were subsequently verified using multi-color fluorescent microscopy (Fig. S2A). Of note, 4 h stimulation with PMA/ionomycin did not shift CD45RA to CD45RO cells in these experiments (Fig. S2B)

Figure 4.

Cytokine production by CD20+ T cells. PBMCs from healthy volunteers were stimulated for 4 h using PMA/Ionomycin in the presence of Brefeldin A and intracellular production of IFNγ (A), IL-4 (B) and IL-17A (C) assessed in the CD3+ CD20− and CD3+ CD20+ populations assessed using flow cytometry. Anti-CD45RO-APC was included to identify memory T cell populations.

The percentage of CD20+ T cells is increased in ascites fluid of ovarian cancer patients

Patients with OC had CD20+ T cell populations in the peripheral blood that closely matched that found in healthy volunteers, including a predominant TH1/TC1 TEM phenotype (Fig. 5A), with perhaps a minor trend toward a more TTD phenotype (Fig. 5D). However, in peritoneal ascites fluid of OC patients the population of CD20+ T cells was significantly expanded and comprised approximately 23.4 ± 6.8% of all ascites fluid T cells (Fig. 5B; left panel and Fig. 5C). These CD20+ ascites fluid T-cells were predominantly of TEM phenotype (Fig. 5B and D) and were also skewed toward the TH1/TC1 cytokine production (Fig. S3A–C).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate that T cells rapidly acquired CD20 (< 15 min.) when co-cultured in vitro with B cell leukemic lines or primary B-cells. In peripheral blood and in ascites fluid these CD20+ T cells were phenotypically characterized as effector memory T-cells that produced IFNγ. Further, this CD20+ T-cell population was significantly enriched in ascites fluid in OC patients.

Data from the current study suggest that CD20+ T cells may arise as a result of membrane exchange upon T cell : B cell contact. These findings are consistent with the previously reported transfer of HLA-DR from B cells to T cells.13 Concurrent with uptake of CD20 a similar uptake of HLA-DR by T cells was detected. It is therefore conceivable that CD20+ T cells originate following antigen-presentation by B cells and concomitant transfer of both HLA-DR and CD20 (and possibly other molecules). Indeed, the absence of CD20+ T cells in cord blood seems to support a role for the development of CD20+ T cells during immune responses later in life.

In our cohort of healthy volunteers and OC patients (> 30 individuals in total), approximately 2–10% (6.0 ± 3.8%) of circulating T cells in the peripheral blood express CD20 on the T cell surface. Furthermore, multiple samplings of the same healthy volunteer in a 2 week interval revealed highly consistent levels of this subpopulation (data not shown). These findings are in line with other recent reports on the relative percentage of CD3+ CD20+ T cells in the peripheral blood of German and British cohorts of healthy volunteers and patients with rheumatoid arthritis.19,20

Importantly, as CD20 is considered a prototypical B cell marker, studies on CD20+ T cells should take exceptional care to exclude any contamination by B cell-T cell doublets. Indeed, Henry et al. have previously suggested that CD20+ T cells in peripheral blood may be an artifact of flow cytometry resulting from doublets.21 However, we and others have demonstrated that single isolated T cells can and do have CD20 molecules at their cell surface.20 Nevertheless, we addressed these concerns further in our current study in several ways. First, we have used a highly stringent gating strategy to exclude not only doublets (forward scatter pulse width area), but also B cells based on the co-expression of CD19. Second, analysis of CD20+ T cell phenotype by confocal microscopy did not reveal any signs of B cell-T cell doublets, whereas we could clearly identify CD3+ CD20+ cells with CD20 levels distinct from a B cell (∼10–100 fold lower). Third, CD3+ CD20+ T cells could be isolated from peripheral blood by single cell sorting, activated with a cocktail of anti-CD3 and IL-2 and remained a single homogenous population presenting CD20 and expressing typical T cell markers. Fourth, cord blood T cells were largely devoid of a CD3+ CD20+ T cells under identical staining conditions. Fifth, B cell contamination in our phenotypical analysis should have resulted in a distinct population with characteristic B cell expression levels for CD45RO/CCR7/CD25/CD127/ HLA-DR, but no such population was observed. Therefore, we are confident of and support Wilk et al. on the validity of CD3+ CD20+ T cells in peripheral blood.19

CD20+ T cells from peripheral blood were found to display a typical effector memory (TEM) phenotype and were skewed toward a CD8+ (∼60%) Th1/Tc1 subtype. Furthermore, when performing phenotypical analysis of the CD20+ T cell subpopulation in the peripheral blood or ascites fluid of patients with OC, we found that this phenotype was fully conserved within individuals with OC. Of note, while Wilk et al. primarily examined T cell markers associated with activation status, their observed percentage of CD45RO expressing cells in CD20+ vs. CD20− cells is almost identical to the one observed by us (Wilk et al. 72% vs. 42%; this study 76.7 ± 1.9% vs. 49 ± 2.4%).19,23

As CD20+ T cells are predominantly TEM cells with a Tc1 (IFNγ+ CD8+) phenotype, it is tempting to speculate that these cells function as a tumor suppressor population. Indeed, infiltration of TEM cells into OC tumors has been correlated to improved disease progression and Tc1 cells have been extensively described as the main mediators of the antitumor T cell response.6 However, the relative levels of CD20+ T cells in ascites fluid were highly consistent and did not appear to correlate to disease stage, therapy response or expected prognosis. Alternatively, TEM cells and by extension CD20+ T cells might be expanded in the peritoneal cavity as a result of increased homing to peripheral tissues consistent with the function of TEM cells vs. central memory T cells.

One outstanding question that remains is whether there are functional differences between CD20+ and CD20− T-cells as a consequence of CD20 expression on the T-cell surface. On B-cells, CD20 ligation by agonistic antibodies was reported to induce intracellular calcium fluxes and thereby to augment B-cell receptor signaling.24–26 However, the natural ligand of CD20 is currently unknown and whether calcium signaling is the primary signal for CD20 in its natural context remains to be determined. In this respect, B cells from a juvenile patient with CD20 deficiency did not differ in basal calcium flux in response to treatment with IgG or IgM, but were defective in antibody production.27 Further insight into the role of CD20 may help uncover whether CD20 has a function on CD20+ T-cells.

In conclusion, we describe here the in depth characterization of CD20+ T cells from peripheral blood as CD8+ effector memory and IFNγ producing T-cells. Further, we document a significant expansion of this population in the ascites fluid of patients with OC and provide insights into the possible origin of these cells. Further studies should aim to elucidate whether CD20+ T cells occur de novo as a result of B cell antigen presentation in patients with OC and whether this T-cell population is involved in antigen-specific immunity against OC.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-CD3-CyQ, anti-CD3-PE, anti-CD4-PE, anti-CD8-PE, anti-CD19-PE, anti-CD20-FITC, and anti-HLA-DR-PE were from IQ products (Groningen, The Netherlands). Anti-CD45RO-APC, anti-CCR7-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD25-PE, anti-CD127-APC, anti-IFNy-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-IL-4-PerCP-Cy5.5, and anti-IL-17A-PerCP-Cy5.5 were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Fluorescently-conjugated isotype controls for each antibody were ordered from the same companies as indicated above. The agonistic anti-CD3 antibody WT-32 was kindly provided by Dr. B.J. Kroesen (University of Groningen, The Netherlands). IL-2 was purchased from immunotools (Friesoythe, Germany).

Cell lines and trogocytosis assays

The T cell line Jurkat and B cell lines Z138 and Raji were purchased from the ATCC. Trogocytosis was assessed by co-culturing Jurkat or primary T cells with Z138 or Raji for various time points as indicated, followed by flow cytometric analysis of cell surface markers as described below.

Isolation and activation of primary (patient-derived) immune cells

Experiments were approved by the local Medical Ethical Committee and patients/healthy volunteers signed for informed consent. Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) from blood of healthy donors or cancer patients were isolated using standard density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep; Axis-Shield PoC As) as previously described.22 Tumor-associated immune cells were isolated from the primary ascites cultures using ammonium chloride lysis. Activated T cells were generated by culturing PBLs with anti-CD3 mAb WT-32 (0.5 μg/mL) and IL-2 (100 ng/mL) for 48 h. Cord blood cells (following CD34+ depletion by magnetic cell sorting) were kindly provided by Prof. Dr. J.J. Schuringa (University of Groningen, The Netherlands)

Cell surface immunofluorescence staining

For determining the percentage of CD20+ T cells, 0.5 × 106 cells per indicated condition were stained with anti-CD3-CyQ, anti-CD19-PE, and anti-CD20-FITC. For phenotypic characterization of T cells, 0.5 × 106 cells per indicated condition were stained with anti-CD3-PE (or alternatively anti-CD4-PE or anti-CD8-PE), anti-CD20-FITC, anti-CD45RO-APC, and anti-CCR7-PerCP-Cy5.5. Expression of IL-2Rα, IL-7Rα or HLA-DR was determined by staining 0.5 × 106 cells per indicated condition with anti-CD3-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD20-FITC, anti-CD25-PE and anti-CD127-APC. All staining was carried out for 60 min on ice in the dark and specific staining of all indicated markers was confirmed using relevant isotype controls. Staining was analyzed on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometre (Becton Dickinson). Data were plotted using Cflow software (Becton Dickinson). Positively and negatively stained populations were calculated by quadrant dot plot analysis. For all experiments, cells were carefully gated on forward scatter pulse width area to exclude doublets and B cells excluded from the analysis by co-expression of CD19.

Intracellular immunofluorescence staining

Immune cells were washed and stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin in the presence of brefeldin A for 4 h. Subsequently, cells were washed in wash buffer (phosphate buffered saline, 5% fetal bovine serum, 0.1% sodium azide) and stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD3, FITC-conjugated anti-CD20, and APC-conjugated anti-CD45RO for 45 min on ice. Cells were subsequently fixed with Reagent A (Caltag, An Der Grab, Austria) for 10 min. After washing, cells were resuspended in permeabilization Reagent B (Caltag) and labeled with either anti-IFNγ, anti-IL-4, or anti-IL-17A antibodies conjugated to PerCP-Cy5.5 for 20 min in the dark. Relevant isotype-matched antibodies were used as controls. After staining, the cells were washed and analyzed on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometre (Becton Dickinson). Data were plotted using Cflow software (Becton Dickinson). Positively and negatively stained populations were calculated by quadrant dot plot analysis.

Two-photon confocal microscopy

Immune cells were stained essentially as described above for intracellular immunofluorescence with the exception that no anti-CD45RO-APC antibody was added during the initial cell surface staining after stimulation with PMA/Ionomycin. Cells were subsequently analyzed on an inverted LSM 780 NLO Zeiss microscope (Axio Observer.Z1) with the kind help of Ing. K.A. Sjollema.

Multi-color immunofluorescence on paraffin-embedded tissue

Tonsil and tumor slides were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and antigen retrieval was performed in a citrate buffer (10 mM citrate, pH 6.0). After cooling, endogenous peroxidase was blocked in a 0.3% H2O2 solution for 30 min. Slides were then incubated overnight with rat anti-human CD3 (Abcam, ab5690, 1:20) and mouse anti-human CD20 (DAKO, clone L26, 1:100). CD3 signal was visualized using a HRP-conjugated goat-anti-rat secondary antibody and Cy5 tyramide signal amplification according to the manufacturer's instructions (PerkinElmer). CD20 was visualized using AlexaFluor488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody. Counterstaining was done by 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Slides were mounted in Prolong Gold (Life Technologies) and stored in the dark at RT. Immunofluorescent slides were scanned using a TissueFaxs imaging system (TissueGnostics, Austria). Processed channels were merged using Adobe Photoshop.

Statistical Analysis

Data reported are mean values ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey–Kramer post-test or, where appropriate, by two-sided unpaired Student's t-test. p < 0.05 was defined as a statistically significant difference. Where indicated * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and Dutch Cancer Society (KWF) to EB, and a grant from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation to MdB. Part of the work has been performed at the UMCG Imaging and Microscopy Center (UMIC), which is sponsored by NWO-grants 40-00506-98-9021 (TissueFaxs) and 175-010-2009-023 (Zeiss 2p).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1. Köbel M, Kalloger SE, Huntsman DG, Santos JL, Swenerton KD, Seidman JD, Gilks CB. Differences in tumor type in low-stage versus high-stage ovarian carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2010; 29: 203-11; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181c042b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 2008; 58: 71-96; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3322/CA.2007.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colombo N, Peiretti M, Parma G, Lapresa M, Mancari R, Carinelli S, Sessa C, Castiglione M. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2010; 21 Suppl 5: v23-30; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/annonc/mdq244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holschneider CH, Berek JS. Ovarian cancer: epidemiology, biology, and prognostic factors. Semin Surg Oncol 2000; 19: 3–10; PMID:10883018; DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1098-2388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hwang W-T, Adams SF, Tahirovic E, Hagemann IS, Coukos G. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating T cells in ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2012; 124: 192-8; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.09.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D, Gimotty Pa, Massobrio M, Regnani G, Makrigiannakis A, Gray H, Schlienger K, Liebman MN, Rubin SC, Coukos G. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 203-13; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa020177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gooden MJM, de Bock GH, Leffers N, Daemen T, Nijman HW. The prognostic influence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2011; 105: 93-103; PMID:NOT_FOUND; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/bjc.2011.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leffers N, Gooden MJM, de Jong Ra, Hoogeboom B-N, ten Hoor Ka, Hollema H, Boezen HM, van der Zee AGJ, Daemen T, Nijman HW. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating T-lymphocytes in primary and metastatic lesions of advanced stage ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2009; 58: 449-59; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-008-0583-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Milne K, Köbel M, Kalloger SE, Barnes RO, Gao D, Gilks CB, Watson PH, Nelson BH. Systematic analysis of immune infiltrates in high-grade serous ovarian cancer reveals CD20, FoxP3 and TIA-1 as positive prognostic factors. PLoS One 2009; 4: e6412; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0006412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nielsen JS, Sahota Ra, Milne K, Kost SE, Nesslinger NJ, Watson PH, Nelson BH. CD20 +tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes have an atypical CD27- memory phenotype and together with CD8+ T cells promote favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 3281-92; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodríguez-Pinto D. B cells as antigen presenting cells. Cell Immunol 2005; 238: 67-75; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Constant S, Sant’Angelo D, Pasqualini T, Taylor T, Levin D, Flavell R, Bottomly K. Peptide and protein antigens require distinct antigen-presenting cell subsets for the priming of CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 1995; 154: 4915-23; PMID:16574086; hhtp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.02.005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martínez-Martín N, Fernández-Arenas E, Cemerski S, Delgado P, Turner M, Heuser J, Irvine DJ, Huang B, Bustelo XR, Shaw A, et al. T cell receptor internalization from the immunological synapse is mediated by TC21 and RhoG GTPase-dependent phagocytosis. Immunity 2011; 35: 208-22; PMID:21820331; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daubeuf S, Aucher A, Bordier C, Salles A, Serre L, Gaibelet G, Faye J-C, Favre G, Joly E, Hudrisier D. Preferential transfer of certain plasma membrane proteins onto T and B cells by trogocytosis. PLoS One 2010; 5: e8716; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0008716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aucher A, Magdeleine E, Joly E, Hudrisier D. Capture of plasma membrane fragments from target cells by trogocytosis requires signaling in T cells but not in B cells. Blood 2008; 111: 5621-8; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Daubeuf S, Lindorfer Ma, Taylor RP, Joly E, Hudrisier D. The direction of plasma membrane exchange between lymphocytes and accessory cells by trogocytosis is influenced by the nature of the accessory cell. J Immunol 2010; 184: 1897-908; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.0901570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Joly E, Hudrisier D. What is trogocytosis and what is its purpose? Nat Immunol: 2003; 4: 815; PMID:12942076; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ni0903-815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qureshi OS, Zheng Y, Nakamura K, Attridge K, Manzotti C, Schmidt EM, Baker J, Jeffery LE, Kaur S, Briggs Z, et al. Trans-endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: a molecular basis for the cell-extrinsic function of CTLA-4. Science 2011; 332: 600-3; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1202947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilk E, Witte T, Marquardt N, Horvath T, Kalippke K, Scholz K, Wilke N, Schmidt RE, Jacobs R. Depletion of functionally active CD20+ T cells by rituximab treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60: 3563-71; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/art.24998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eggleton P, Bremer E, Tarr JM, de Bruyn M, Helfrich W, Kendall A, Haigh RC, Viner NJ, Winyard PG. Frequency of Th17 CD20+ cells in the peripheral blood of rheumatoid arthritis patients is higher compared to healthy subjects. Arthritis Res Ther 2011; 13: R208; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/ar3541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gabriel SE, Crowson CS. Ischemic heart disease and rheumatoid arthritis: comment on the article by Holmqvist et al. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62: 2561; author reply 2561; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/art.27553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. De Bruyn M, Wei Y, Wiersma VR, Samplonius DF, Klip HG, van der Zee AGJ, Yang B, Helfrich W, Bremer E. Cell surface delivery of TRAIL strongly augments the tumoricidal activity of T cells. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17: 5626-37; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holley JE, E. Bremer AC, Kendall M, de Bruyn W, Helfrich JM, Tarr J, Newcombe NJ, Gutowski P Eggleton. CD20+inflammatory T-cells are present in blood and brain of multiple sclerosis patients and can be selectively targeted for apoptotic elimination. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2014; 3: 650-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.msard.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bubien JK, Zhou LJ, Bell PD, Frizzell RA, Tedder TF. Transfection of the CD20 cell surface molecule into ectopic cell types generates a Ca2+ conductance found constitutively in B lymphocytes. J Cell Biol 1993; 121: 1121-32; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.121.5.1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kanzaki M, Lindorfer MA, Garrison JC, Kojima I. Activation of the calcium-permeable cation channel CD20 by alpha subunits of the Gi protein. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 14733-9; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hofmeister JK, Cooney D, Coggeshall KM. Clustered CD20 induced apoptosis: Src-family kinase, the proximal regulator of tyrosine phosphorylation, calcium influx, and caspase 3-dependent apoptosis. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2000; 26: 133-43; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/bcmd.2000.0287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuijpers TW, Bende RJ, Baars PA, Grummels A, Derks IA, Dolman KM, Beaumont T, Tedder TF, van Noesel CJ, Eldering E, et al. CD20 deficiency in humans results in impaired T cell-independent antibody responses. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 214-22; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI40231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.