Abstract

VEGFR-2 is expressed on tumor vasculature and a target for anti-angiogenic intervention. VXM01 is a first in kind orally applied tumor vaccine based on live, attenuated Salmonella bacteria carrying an expression plasmid, encoding VEGFR-2. We here studied the safety, tolerability, T effector (Teff), T regulatory (Treg) and humoral responses to VEGFR2 and anti-angiogenic effects in advanced pancreatic cancer patients in a randomized, dose escalation phase I clinical trial. Results of the first 3 mo observation period are reported. Locally advanced or metastatic, pancreatic cancer patients were enrolled. In five escalating dose groups, 30 patients received VXM01 and 15 placebo on days 1, 3, 5, and 7. Treatment was well tolerated at all dose levels. No dose-limiting toxicities were observed. Salmonella excretion and salmonella-specific humoral immune responses occurred in the two highest dose groups. VEGFR2 specific Teff, but not Treg responses were overall increased in vaccinated patients. We furthermore observed a significant reduction of tumor perfusion after 38 d in vaccinated patients together with increased levels of serum biomarkers indicative of anti-angiogenic activity, VEGF-A, and collagen IV. Vaccine specific Teff responses significantly correlated with reductions of tumor perfusion and high levels of preexisting VEGFR2-specific Teff while those showing no antiangiogenic activity had low levels of preexisting VEGFR2 specific Teff, showed a transient early increase of VEGFR2-specific Treg and reduced levels of VEGFR2-specific Teff at later time points – pointing to the possibility that early anti-angiogenic activity might be based at least in part on specific reactivation of preexisting memory T cells.

Keywords: anti-angiogenic treatment, cancer immunotherapy, oral vaccination, pancreatic cancer, VEGFR2

Introduction

Cancer vaccines aim to stimulate the immune system to target tumor-associated structures through either an antibody and/or T-cell mediated attack. Common to all targeted cancer vaccines in clinical development is an intramuscular or intradermal site of vaccination. An alternative approach not yet clinically tested is oral vaccination, using the large surface area of the intestine for immune stimulation. Oral Salmonella Typhimurium (S. Typhi) mediated DNA vaccination has successfully been used in many murine tumor models.1 An analogous human-specific carrier strain, S. Typhi Ty21a, has been thoroughly studied, and is a widely used vaccine for the prevention of typhoid fever.2

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2/KDR/Flk-1) is a high-affinity receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) and mediates most of the VEGF-A related endothelial growth and survival signals.3 VEGFR-2 is highly expressed on tumor vasculature as well as on certain tumor cells.4 Beyond expression levels, the modulation of tumor growth with anti-VEGF-A and VEGFR-2 antibodies (bevacizumab, civ-aflibercept, ramucirumab) and small-molecule VEGFR-2 inhibitors in cancer patients has added to the validation of VEGFR-2 as a therapeutic target in several cancer indications.5,6

VXM01 is an orally available T-cell vaccine, based on live, attenuated S. Typhi Ty21a carrying a eukaryotic expression plasmid, which encodes VEGFR2.7 A murine analog of VXM01 has shown consistent anti-angiogenic and antitumor activity in different tumor types in several animal studies.1,8 This first-in-human study was designed to assess the safety and tolerability, the immune responses to and the anti-angiogenic potential of escalating doses of VXM01.

Results

Between December 2011 and October 2012, 79 patients were referred and screened for the study. Fourty-five patients were enrolled and randomized (Fig. S1). Although, there were no statistical differences in the demographic baseline disease characteristics of the patients between the two groups (Table 1), the placebo group had a shorter median time since diagnosis, and a lower proportion of patients with systemic disease and high baseline CA19.9 (elevated and >1000 U/mL).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| VXM01 (n = 30) | Placebo (n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median Age (years (range)) | 65 (37–82) | 68 (55–73) |

| Sex: | ||

| Men | 18 (60%) | 9 (60%) |

| Women | 12 (40%) | 6 (40%) |

| Race: | ||

| Caucasian | 29 (97%) | 15 (100%) |

| Asian | 1 (3%) | 0 |

| Karnofsky performance status: | ||

| 100 | 11 (37%) | 6 (40%) |

| 90 | 14 (47%) | 4 (27%) |

| 80 | 5 (17%) | 5 (33%) |

| Extent of disease: | ||

| Locally advanced | 5 (17%) | 7 (47%) |

| Metastatic | 25 (83%) | 8 (53%) |

| Time from diagnosis: | ||

| Median (months (range)) | 8 (1–51) | 6 (2–27) |

| Level of carbohydrate antigen 19.9 (IU) | ||

| Normal | 8 (27%) | 6 (40%) |

| Elevated, <1000 | 13 (43%) | 5 (33%) |

| Elevated, >1000 | 9 (30%) | 2 (13%) |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (13%) |

| Previous therapy other than gemcitabine | ||

| Erlotinib | 1 (3%) | 0 |

| Folfirinox | 0 | 1 (7%) |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (7%) |

All patients completed the treatment and the 10-d in-house study phase. Three patients discontinued the study before day 38 and 6 further patients before the 3 mo visit (Fig. S1); at both time points, not all patients could be examined, mostly because of worsened health status.

We did not observe any dose-limiting toxicity, and thus the maximum tolerated dose was not reached. A detailed description of treatment related toxicities for both study groups is provided in Table S1. The most frequent AE of any grade was abdominal pain, which was equally observed in both groups (27%). Diarrhea (27% vs. 7%) and a decrease in lymphocytes (20% vs. 0) and platelets (17% vs. 0) were the most prominent AEs skewed toward the VXM01 treatment group. Observed decreases in lymphocytes and platelets were without clinical symptoms, and normalized without intervention. There were no signs for dose-dependency of these and other AEs.

One patient in each of the two highest dose groups had a transient VXM01-excretion in the stool directly after vaccination. Subsequent stool cultures were negative without any antibiotic intervention. All other blood, stool, urine, or tears specimens collected throughout the study for all subjects tested negative for VXM01.

Six patients, five on VXM01 and one placebo patient, had a detectable pre-existing antibody response against the carrier bacterium before administration of study medication at day 0 (mean antibody index 1.75; range 1.23–2.40). Seroconversion occurred in the two highest dose groups; two patients (33%) receiving 109 CFU VXM01 and three patients (50%) receiving 1010 CFU VXM01 had significant increases in anti-LPS antibodies; mean antibody indices increased from 0·36 (range 0·10–0·66) on day 0 to 2·20 (range 1·46–3·23) on day 10.

According to the specific IFNγ Elispot response criteria, we detected preexisting VEGFR2-specific T cells before vaccination in 19 of 30 VXM01-treated patients and in 10 of 14 evaluated placebo treated patients (range 9–270 spots; median 78 spots per 105 T-cells, Fig. 1A). All 44 evaluated patients had a median VEGFR2-specific ELISpot count at baseline of 34 spots per 105 T cells. Besides VEGFR2 specific T cell response, we also analyzed T cell responses against common recall antigens derived from CMV and adenovirus and against an unrelated pancreatic cancer associated tumor antigen, MUC1 which both served to determine the target specificity of vaccination induced T cell responses. The entire Elispot response kinetic against these antigens and thereof derived fold increase of IFNγ spot counts in VEGFR2 stimulated test wells compared to negative control wells, is shown for one representative patient of the VXM01 treated group in Fig. 1B, C, and D and in Fig. S2, respectively and demonstrates in this patient after the vaccination a consistent increase in VEGFR2 specific T cells and a concomitant but rather transient T cell response against MUC1.

Figure 1.

(A). Preexisting VEGFR2-specific T effector cells detected immediately at d0 in N = 19 VXM01 and 10 placebo patients with significant increased spot counts in test wells compared to negative control wells as determined by IFNγ Elispot assay. Frequencies of VEGFR2-specific T cells are indicated for each patient by individual dots as difference in mean spot numbers between wells containing VEGFR2 and neg. control antigens. (B). T cell response of one representative VXM01 patient before (d0) and at subsequent time points after the vaccination against negative control antigens (huIg), recall antigens (CMV+Adenov.), VEGFR2 and MUC1 as assessed by IFNγ Elispot analysis. Total spots per well (1 × 105 TC/well) are shown in (C), the respective fold change between mean spots in VEGFR2 compared to Ig containing negative control wells of this patient are shown in (D). Error bars show mean + SEM of triplicate wells.

Cumulative data of antigen specific T cell responses against the different test and control antigens are shown in Fig. 2A and Fig. S3 for all tested samples and also for the subgroup who fully completed the 3 mo observation period. We consistently observed the strongest responses against common recall antigens, while T cell responses against MUC1 were weak in both the vaccinated and placebo group.

Figure 2.

Cumulative T cell responses against recall antigens, VEGFR2 and MUC1 (A) or VEGFR2 only (B-D) in vaccinated VXM01 (black circles) or placebo patients (white circles). Antigen specific T cell responses are shown for both groups as fold increase of IFNγ spots in test wells over neg. control wells (A, B), or fold change of VEGFR2 specific T cell response at different time points after vaccination (as determined by fold change of test wells over neg. control wells) over respective values before vaccination (d0) (C, D). Cumulative analysis of all collected samples is shown in the left figure panel, while cumulative data of those patients who completed the observation period of 3 mo are shown in the right panel. Individual courses of VEGFR2 T cell responses over time are shown in D. Mean and SEM are depicted by error bars. *; a statistical trend toward higher increases of VEGFR2 specific T cell responses after 38 d in the vaccinated group compare to the placebo group was detected by two sided student's t-test. (A, B) completed time course placebo group n = 8 and VXM01 n = 19. In C and D placebo n = 7, VXM01 n = 18 (patient 10701 und 10702 excluded due to false positive d0 response).

VEGFR2 specific T cell responses as determined by IFNγ Elispot were compared between the VXM01 group and placebo group in three different ways in order to assess the consistency of observed differences between the groups, namely in regard to (i) the fold increase in IFNγ spot numbers between VEGFR2 stimulated test wells and negative control stimulated wells (Fig. 2B), (ii) the fold increase of VEGFR2 specific T cell response over preexisting levels determined at d0 (Figs. 2C, D) and (iii) by grading the increase of VEGFR2 specific TC responses (Figs. 3A–C). In order to avoid misinterpretations due to incomplete data sets from individual patients we did not only assess cumulative data from all obtained samples but compared them to data obtained from patients who fully completed the observation period of 3 mo. Due to the small number of patients in each dose group, we did not conduct comparisons between the different dose groups but instead analyzed all vaccinated and placebo patients en bloc.

Figure 3.

Graded strength of treatment-associated VEGFR2 responses (as determined by the difference between IFNγ spots in test wells and neg. control wells) in vaccinated (A, C black circles) or placebo patients (B, C open circles based on the fold increase over d0 defining no increase as grade 0, increase < 3 fold as grade 1, increase >3 fold to <5 fold as grade 2 and increase >5 fold as grade 3. In A and B Each dot represents a value of one individual patient. In (C) cumulative data are represented as mean, SEM are depicted by error bars (n = 30 vaccinated and n = 11 placebo).

We observed an initial average decline of VEGFR2-specific T cells during the vaccination phase which was followed by an increase of absolute numbers of VEGFR2-specific spots (data not shown) resulting in an increased ratio of VEGFR2 specific spots over the neg. control which peaked at day 21 and subsequently resulted in higher levels of VEGFR2 specific T cells compared to placebo patients. We did not observe consistently increased T cell responses against CMV and only minor increases of T cell responses against MUC1 in vaccinated over placebo patients (Figs. S4A, B). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that salmonella induced antigen unspecific inflammation may support maintenance and expansion of pre-existing memory T cells against these antigens or an increase of MUC1-specific T cell responses through antigen spreading. The average development of VEGFR2-specific T cell response is comprehensively shown in Fig. 2C and D as fold increase over d0 and demonstrates an initial peak at d21 with an average 3.8 fold increase of VEGFR2 specific T cells for the entire vaccination cohort and a 4.1 fold increase for those patients who fully completed the 3 mo observation period. Increased VEGFR2 specific T cell responses were maintained in the vaccination group until the end of the observation period (2.2 and 2.2 fold increase over d0, respectively). While the average fold increase over d0 did not indicate an initial reduction of VEGFR2 specific responses in the vaccinated group, this was apparent when assessing the median fold increase over d0 levels which demonstrate a sharp decline and subsequent increase after d10 (Figs. S5 A, B).

We also observed in the placebo group a transient decrease in VEGFR2 specific T cells that was followed by a similar though not as pronounced and slightly earlier increase (peak at day 14) compared to the one observed in the vaccinated cohort, suggesting that the preceding course of gemcitabine treatment might also influence tumor antigen specific T cell responses – e.g. through reactivating pre-existing T cells by release of tumor antigens in the context of immunogenic cell death or through depletion of myeloid derived suppressor cells. To exclude the possibility that small differences in the time interval between gemcitabine pretreatment and vaccination between the study patients impacted on VEGFR2 specific T cell levels, we compared patients vaccinated 3–4 d or 7 d after chemotherapy and detected no considerable differences of T cell counts in negative control and VEGFR2 test wells on day 0 or after the vaccination (data not shown).

However, in contrast to vaccinated patients, VEGFR2 specific T cell responses strongly declined at later time points in the placebo group (average of 0.6 fold; median of 0.2 fold change over d0 after 3 mo).

We also graded the strength of treatment-associated VEGFR2 responses based to the fold increase over d0 defining no increase as grade 0, increase < 3 fold as grade 1, increase >3 fold to <5 fold as grade 2 and increase >5 fold as grade 3. While in the placebo group higher (grade 2–3) responses were only detectable within the first 21 d, these were observed in the vaccinated group over the whole observation period, demonstrating an increase of VEGFR2 specific memory T cells through the vaccine (Figs. 3A–C). We finally explored in selected patients who showed a clear increase (grade 3) of VEGFR2 specific T cells after the vaccine whether VEGFR2-reactive CD8+ and/or CD4+ T cells were increased by the vaccine and whether they exerted a poly functional phenotype which is most closely correlated with clinical efficacy of cancer immunotherapies and characterized by simultaneous secretion of IFNγ, TNF-α, and IL-2.9,10 To this end, we assessed in few selected patients by multicolour flow cytometry the secretion of these cytokines by VEGFR2 stimulated T cells using common cytokine capture assays. Respective data from one patient are shown in Fig. S6, demonstrating an increase of multifunctional VEGFR2 reactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells until d21 after the vaccination that secrete not only IFNγ or TNF-α but also IL-2.

Taken together, we consistently observed higher VEGFR2 specific T effector cell responses in the vaccinated patient group compared to the non-vaccinated group particularly after 38 d. Initial changes in VEGFR2 specific T cell responses were to some extent also observed in the placebo group and thus hint toward the possibility of transient influences by the preceding gemcitabine treatment on tumor specific T cell responses. Due to the considerably small size of the phase I study cohorts and due to a considerable heterogeneity in the response patterns within both, the placebo and the vaccinated group, the statistical significance of differences between these groups were low. However, we detected a statistical trend toward higher increases in VEGFR2 specific T effector cell responses over d0 values in the vaccinated group after 38 d (p = 0.053, Fig. 2C).

The vaccine encoded the full length VEGFR2 sequence with embedded HLA-II restricted peptide epitopes which might enable not only CD4+ T helper responses but also the activation of immune suppressive antigen specific regulatory T cells (Treg). We therefore studied the frequencies and target specificity of the latter. Treg frequencies among CD4+ T cells were determined by multicolour flow cytometry, defining Treg as CD4pos, CD25pos, FoxP3pos, and CD127neg (Fig. 4A). Overall, we did not determine major differences in Treg frequencies over time nor between the placebo and VXM01 group, as observed minor alterations were not consistently detectable in both the entire sample cohort and in the subgroup of patients with fully completed time courses (Fig. 4B). Similarly, we also did not detect any correlation between the numbers of Treg and cytokine secreting effector T cells (data not shown). The activity of VEGFR2 responsive Treg was assessed by an established functional assay11 that is based on the fact that after antigen specific activation Treg acquire strongly increased T cell suppressive activity. We stimulated purified Treg from patients with VEGFR2 or neg. control antigens, afterwards cocultured them with polyclonally activated autologous conventional T cells and subsequently determined their proliferative activity which was significantly reduced when VEGFR2 reactive Treg were present in the test sample. A representative experiment from one patient demonstrating the presence of VEGFR2-reactive but not MUC1-reactive Treg is shown in Fig. 4C. Altogether, we did not observe strong differences in VEGFR2 specific Treg activity between the VXM01 and placebo groups. Still, average VEGFR2 specific suppressive Treg activity slightly increased in placebo treated patients from 7.8% on d0 to 17.8% after 3 mo (Fig. 4D), while vaccinated patients showed an overall decline in antigen specific Treg responses particularly at later time points (15.5%–10.6%, respectively). Notably, a transient but considerable increase of VEGFR2 specific Treg responses was observed in vaccinated patients immediately (4 d) after the vaccination but not in the placebo group (Fig. 4D) which might hint toward the possibility that the vaccine caused a transient vaccine specific Treg response at least in some patients.

Figure 4.

Regulatory T cell response in VXM01 and placebo patients. Frequencies of total Treg among CD4+ T cells were determined throughout the observation period in PBMC by flow cytometry on the basis of simultaneous CD3, CD4, CD25, and FoxP3 expression and lack of CD127 expression (A) and separately plotted for vaccinated (all data VXM01 n = 30; completed time course VXM01 n = 25) and placebo (all data vxm01 n = 12; completed time course n = 10) patients (B). C+D. The presence and suppressive activity of VEGFR2 reactive Treg as determined by a functional Treg specificity assay is shown for one representative patient (C), depicting the relative VEGFR2 specific Tcon suppression as percentage reduction of the Tcon proliferation compared to wells containing Treg that were stimulated with negative control antigen (IgG). (D) Cumulative data show the average VEGFR2-specific Treg suppression of Tcon proliferation as the mean and SEM for all obtained samples in the vaccinated (VXM01) or placebo group (left panel) and for those patients who completed the entire observation period (right panel).

In order to explore hints for antiangiogenic activity in vaccinated patients, we evaluated the tumor perfusion by DCE-MRI (Fig. 5A) and assessed established biomarkers of successful anti-angiogenic treatment,12 namely elevated serum levels of VEGF-A, collagen IV and elevated blood pressure. A total of 37 patients, 26 on active and 11 on placebo treatment were examined by DCE-MRI at baseline and at day 38 while 11 and 9 of them, respectively, could be also assessed after 3 mo. After 38 d we detected an average Ktrans reduction of 18% (–18%, Fig. 5B) while the tumor perfusion remained stable in placebo treated patients. Three months post vaccination, Ktrans rebounded slightly in VXM01 patients (n = 18). A subgroup analysis of those 18 patients in the VXM01 group and 9 patients in the placebo group who completed the entire observation period revealed an even more pronounced reduction of tumor perfusion after 38 d in most of the vaccinated patients (–30,4%, p < 0.05 vs. + 3.3%, respectively; Figs. 5B, C).

Figure 5.

Antiangiogenic activity of VXM01. (A–C) Assessment of tumor perfusion Ktrans by MRI-based recording (A; representative picture) of contrast signal enhancement. (B) Cumulative data of tumor perfusion in vaccinated (VXM01) and placebo patients showing the mean and SEM for those patients who provided at least d0 and d38 levels (left panel) and for those who completed the entire observation period (right panel). Individual d0 and d38 values of the latter group are shown in (C). The p value indicates an overall significant reduction of Ktrans levels between d0 and d38 as calculated by wilcoxon test. (D, E) Cumulative data showing the mean and SEM values of collagen IV (D) and VEGF-A (E) serum levels in the vaccinated (VXM01) or placebo group for those patients who provided at least d0 and d38 levels (left panel) and for those who completed the entire observation period (right panel). (F). Highly significant correlation between the change of tumor perfusion between d0 and d38 in VXM01 treated patients who completed the whole observation period and the respective strength of vaccine induced VEGFR2 specific T cell response at day 21 (determined as fold increase over d0).

Increase of VEGF-A and collagen IV after vaccination further supported the observed vaccination effects on tumor perfusion, particularly since we observed a significant inverse correlation between collagen IV serum levels and alterations of tumor perfusion after the vaccination (Fig. S7). Collagen IV was likewise increased by 5% and 23%, respectively in the VXM01 group but not in the placebo group (–1% and –7%, respectively) (Fig. 5D). Average VEGF-A serum levels increased in vaccinated patients from day 0 to day 38 by 34% and by 69% at month 3 vs. a drop of 13% and 13%, respectively, in placebo patients (Fig. 5E). The described changes were consistent in the subgroup of patients having fully completed the 3 mo observation period.

In accordance to these observations, vaccinated patients showed an increased incidence in elevated blood pressure levels (Table S2) and an overall increase of systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 3.6 (± 3.4) mmHg on day 38, while placebo treated patients showed a marked drop of 8.8 (± 6.1) mmHg. Both the increase in the vaccination group and the drop in the placebo group were maintained until month 3. All patients who had developed moderately elevated blood pressure (SBP 160–180 mmHg) under VXM01 treatment (16%) at day 38 had resolved to SBP below 160 mmHg at month 3.

Taken together, we observed consistent evidence for vaccine induced anti-angiogenic activity in VXM01 patients. This was further corroborated by a highly significant correlation between the strength of the preceding systemic VEGFR2 specific T cell response (indicated by the fold change of VEGFR2 specific T cell response at peak levels on day 21 over levels before vaccination) and the magnitude of subsequent changes in tumor perfusion on day 38 (indicated by the difference between Ktransd0 and Ktransd38) (Fig. 5F).

In regard to clinical outcome no apparent differences between the study groups were observed, so far. We detected a partial response at month 3 in one of 18 VXM01 patients (6%) in the VXM01 group vs. 0 in the placebo group (Table S3). This partial response occurred in the highest dose group and was accompanied by a drop in CA19.9 serum levels from 2741 U/mL at day 0 to 162 U/mL at month 3 (–94%). No other patient in the study had marked (>50%) declines in their CA19.9 levels up to month 3. The responding patient also showed a strong drop in tumor perfusion after the vaccination (Ktrans decreased by 48% and 33% on day 38 and month 3) and a strong increase of the VEGFR2 specific T cell response at day 21 (4.8 fold increase over pre-vaccination level).

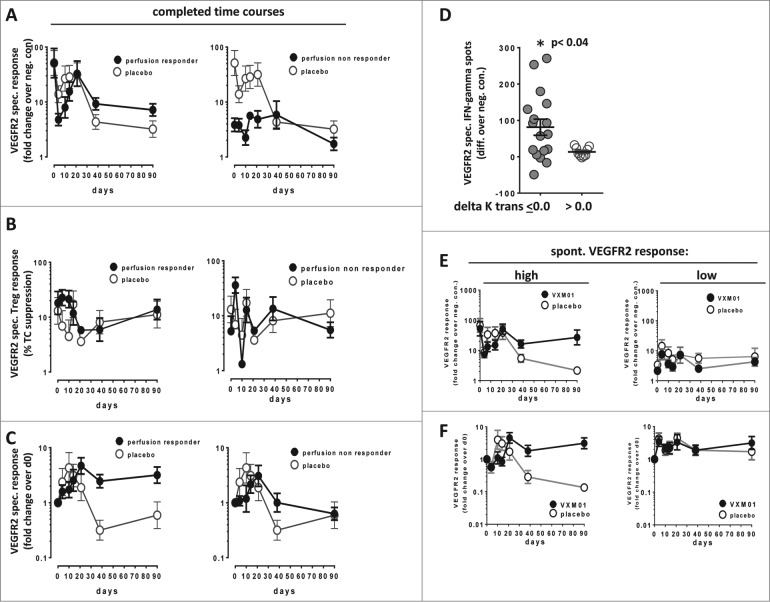

In order to better understand the course of those vaccine induced immune responses that were associated with anti-angiogenic activity, we compared VEGFR2 specific Teff and Treg responses in patients who showed delta Ktrans levels <0.0 or >0.0. Tumor perfusion responders had high VEGFR2 specific T cell responses already before vaccination, showed durable increases of VEGFR2 specific T cells over time and a transient reduction of VEGFR2-specific Treg activity (Figs. 6A–D, Fig. S8). In contrast, tumor perfusion non-responders had significantly lower preexisting levels of VEGFR2 specific T cells, did not develop durable increases of specific T cells but showed a strong initial increase of VEGFR2 specific Treg.

Figure 6.

(A–D) Assessment of VEGFR2 specific T cell responses in tumor perfusion responders and in non-responders. Cumulative T cell responses against VEGFR2 in vaccinated VXM01 patients (black circles) and placebo (open circles) recording VEGFR-2 specific Teff response as fold change over neg. control (A), VEGFR2 specific Treg activity (B) and the change of VEGFR2 specific Teff response over time (fold change over d0) (C). Patients who showed a reduced or stable tumor perfusion (delta Ktrans < 0.0) between d0 and d38 are shown in the left figure panel while patients showing increased tumor perfusion after 38 d are shown in the right figure panels, respectively. Only patients who completed the entire observation period were included. Respective cumulative data of the whole placebo group (open circles) are shown for comparison. (D) Significantly increased levels of preexisting VEGFR2 specific Teff cells in VXM01 patients showing reduced or stable tumor perfusion 38 d after vaccination. The p value indicates the statistical difference between tumor perfusion responders and non-responders as determined by two-sided student's t test. (E-F) Cumulative T cell responses against VEGFR2 in vaccinated VXM01 patients (black circles) or placebo patients (open circles) with high preexisting VEGFR2 specific Teff levels (above median of the entire patient group) (left panel) or low levels of preexisting VEGFR2 specific Teff (below median) (right panel) recording Mean+SEM of VEGFR2 specific Teff response as fold change over negative control (E) or the change of VEGFR2 specific Teff response over time (fold change over d0). (F). Only patients who completed the entire observation period were included.

Since a major difference in the immune response pattern between tumor perfusion responders and non-responders was related to the level of the preexisting T cell response, we also stratified all patients (both VXM01 and placebo treated) according to the strength of the pre-existing VEGFR2 specific T cell response (above vs. below median fold change over neg. control). Compared to the respective placebo group we observed considerably increased T cell responses after vaccination only in patients with elevated preexisting VEGFR2-specific T cell responses (Figs. 6E, F).

Taken together, these findings suggest that early anti-angiogenic effects of the vaccine as defined by reduced blood perfusion after 38 d were mainly mediated through a vaccine-induced reactivation of preexisting VEGFR2 specific memory/effector T cells.

Discussion

We here show that VXM01 – a first in kind, oral T cell vaccine, based on recombinant, live, attenuated S. Typhi and targeting VEGFR2-expressing cells – can be safely administered. Side effects were mostly mild in severity and manageable, and occurred in similar frequencies in the control group. A drop in certain blood cell counts (lymphocytes, platelets) was the most striking differences between the placebo and the treatment groups, but these were transitory and did not require intervention. Typical vaccination side effects, such as fever and fatigue, were rare and not noticeably associated with treatment. While hypertension was also not recorded as particularly associated with treatment as a side effect, blood pressure data analysis showed a mild increase in average blood pressure as well as an increased incidence of elevated blood pressure in vaccinated patients. This and the observed drop in platelets and lymphocytes have been described for other anti-angiogenic treatments13. There was no apparent association between side effects and the applied dose during the escalation over five 10-fold dose increases. Only excretion of VXM01, which was self-limiting, and anti-carrier immunity showed a dose correlation.

We also here report strong hints for the ability of VXM01 to increase poly-functional VEGFR2-reactive CD8+ and CD4+ T effector cell responses in advanced pancreatic cancer patients despite the well-established strong immune suppressive tumor microenvironment in this entity14 which among others causes a particularly low spontaneous tumor T cell infiltration15 and T cell activity in situ. Although we detected a three to four fold increase in the proportions of therapeutically relevant CD4+ and CD8+ T cells coexpressing IL-2 in addition to TNF and/or IFN (reaching 10% and 12% of the entire population of VEGFR2 specific T cells) the majority of VEGFR2 reactive T cells expressed IFN and/or TNF only and thus may represent a population of exhausted T cells.

Surprisingly, among the enrolled patients, a high fraction had significantly elevated levels of detectable T cells directed against VEGFR2 at day 0 and prior to any vaccination. These patients seemed to have reacted spontaneously to increased neovasculature associated with their disease; we did not find similar elevated levels in a cohort of healthy volunteers tested outside the protocol in parallel to this study (our data not shown). Spontaneous T cell responses against tumor cell associated antigens have been detected by us and others in a broad variety of different tumor entities, including pancreatic cancer, before.16,17 Increased frequencies of pre-existing effector/memory T cells correlated with improved survival in other tumors such as malignant melanoma18 and after appropriate antigen specific reactivation spontaneously generated tumor specific memory T cells can efficiently reject autologous tumors in xenotransplant settings19,20 – demonstrating their therapeutic potential.21–24

Long lasting increases in VEGFR2 specific T effector cell responses were particularly observed in patients with higher levels of pre-existing VEGFR2 specific T cells and were often associated with an initial and transient drop in circulating VEGFR2 specific T cells. Such transient drop was not observed for recall antigen specific T cell responses, suggesting that pre-existing VEGFR2 specific T cells were specifically reactivated by the vaccine and subsequently may have been recruited from the peripheral blood into the tissues of the gut or related lymphatic tissues, where the antigen had been expressed through the vaccination. Kinetic studies in mice showed target antigen to be present in the gut until around 48 h post vaccinations, which would explain the reappearance of the T cells in the patient's blood at day 14 and 21. The observed peak at day 21 was reflected in earlier immune kinetic data in mice that showed the peak of a T cell response to occur on or around day 18 (our data not shown). However, the drop of pre-existing VEGFR2 specific T cells was particularly pronounced in those patients who showed a reduction of tumor perfusion after the vaccine and thus may also indicate T cell recruitment into the tumor tissue. It is tempting to speculate that selection of patients with higher frequencies of pre-existing T cells may particularly benefit from the vaccine. Alternatively, the observed lack of angiostatic activity in patients lacking pre-existing T cell responses could potentially be overcome by implementing serial boost vaccinations after the initial priming phase.

Overall, the vaccine did not increase the frequencies of total or VEGFR2 specific Treg. However, we detected a rapid, transient increase of VEGFR2-reactive Treg in those patients who showed only low levels of pre-existing VEGFR2 specific T cells and no reduction in blood perfusion after the vaccination – pointing to the possibility that, at least in the absence of higher preexisting VEGFR2 specific T effector cells, specific Treg might be re-activated or induced by the vaccine. Since activated Treg can efficiently transmigrate through pancreatic cancer vasculature,25 their activation might have contributed to the angiostatic failure of the vaccine in some patients.

Differences in T cell responses were not statistically significant between the placebo and VXM01 group, which was most likely due to (i) heterogeneous response patterns in individual patients, (ii) relatively small numbers of placebo patients (iii) the splitting up of VXM01 patients into five different dose groups and the confounding effect of the preceding gemcitabine treatment. Still, the overall consistent hints for the immunogenicity of the vaccine were further corroborated by the clear indications of anti-angiogenic effects related to VXM01. Despite the fact that ductal pancreatic adenocarcinomas have a relatively low perfusion as compared to other cancer types26 tumor perfusion was markedly reduced in vaccinated but not in placebo patients and within vaccinated patients the extent of anti-angiogenic activity showed a highly significant linear correlation to the strength of the induced VEGFR2 specific T cell response. Further confirmations of the vaccination effect were the associated characteristic changes in serum biomarkers VEGF-A and Collagen IV, and in blood pressure, all previously described as markers of anti-angiogenic efficacy.12

Pancreatic cancer has been shown in the past not to be susceptible to treatment with different anti-angiogenic therapy.27 Response rates to VXM01 on month 3, both in terms of reduction of CA19.9 levels and according to RECIST, were below 10%. One of the weaknesses of this study was that the patient population was not selected from those indications, where anti-angiogenesis had already proven clinical efficacy, such as colorectal cancer, lung cancer, renal cancer, and others,5 and for further development of VXM01 these need to be considered. However, the choice of pancreatic cancer patients, besides being encouraged by preclinical data, allowed us to enter into a first line regimen and fulfill the regulatory requirement of choosing a palliative setting at the same time. We treated a rather homogenous patient population in terms of disease and background therapy, which allowed us to discriminate VXM01 related side-effects from those of disease and background therapy, and to elucidate immunological and anti-angiogenic effects of the vaccine in comparison to a control group. Interestingly, two patients in the VXM01 group had a complete remission of their liver metastases and became eligible to surgery. One of the patients was operated and her primary tumor could be entirely removed; the other patient denied surgery for personal reasons.

Furthermore, the study showed for the first time that oral vaccination with a bacterial vector, carrying a eukaryotic expression plasmid against a tumor associated target antigen can efficiently trigger a productive T-cell response in patients, suggesting that this platform may also be suitable to be used for vaccination against other tumor antigens and for treatment of other tumor entities. The gut is a large, immunologically active and efficient compartment. Moreover, T-cells that are stimulated there may also have higher affinity to mucosal and gastrointestinal compartments and the respective tumor types boding well with indications like colorectal cancer, lung cancer, gastric cancer, or hepatocellular carcinoma.

In conclusion, VXM01 elicits a productive, complex VEGFR2 specific T effector cell response in patients with pancreatic cancer that correlates with anti-angiogenic activity and has a favorable safety profile. Changes indicative of anti-angiogenic efficacy in tumor perfusion, serum biomarkers, and blood pressure in VXM01 treated patients but not in the control arm were recorded. Overall, VXM01 is a promising anti-angiogenic immunotherapy that deserves further clinical assessment in solid tumors.

Patients and Methods

Design and study populations

Our study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation first-in-human phase I trial.7 Eligible patients had inoperable, locally advanced or stage IV pancreatic cancer; completed at least one cycle of gemcitabine treatment; were chemotherapy naïve within 60 d before the screening visit except gemcitabine treatment; had a Karnofsky index above 70; life expectancy of at least 3 mo; and an adequate bone marrow reserve, hepatic and renal function at the start of the trial. For further demographic and baseline characteristics see also Table 1. Patients were not included who had autoimmune disease; major surgery certain cardiovascular diseases, concomitant treatment or treatment in the prior 2 weeks with antibiotics, anti-angiogenic anti-cancer therapy, systemic corticosteroids or any other immunosuppressive agents (for further details see http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01486329).7

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of good clinical practice. It was approved by the relevant regulatory and ethics committees, and all participants provided written informed consent.

The follow-up period for the whole trial is still ongoing and therefore data on the entire study period are not yet available for all patients. We here report the first 3 mo period, only during which also antiangiogenic activity and antigen reactive Treg were assessed.

Randomization and masking

Eligible patients were randomly assigned to VXM01 or placebo with a computer-generated random list. In each of the five dose groups, three patients were assigned to placebo. In order to ensure proper distribution of the three placebo patients, each dose group was divided into three cohorts (containing 2, 3, and 4 participants) with each of these cohorts containing one placebo-treated patient).7 This resulted in a 2:1 randomization. Randomization was concealed so that neither patients, nor the investigator, nor the sponsor knew which agent was being administered. To maintain masking, a sodium carbonate buffered drinking solution containing either VXM01 or saline (placebo) was prepared by personnel not otherwise involved in the study. The data safety monitoring board (DSMB) had access to the random list before their decision to allow escalation of the dose. All patients were included in the safety analysis. Only minor protocol violations were recorded. For other than the safety, biodistribution and anti-S. Typhi immune response analyses, patients were pooled across all dose groups.

Procedures

Patients received oral VXM01 or placebo on day 1, 3, 5, and 7 of the study, starting 3–11 d after the last gemcitabine administration. The starting dose contained 106 colony forming units (CFU) of VXM01. The dose was escalated in factor-of-ten logarithmic steps, after all patients in the second cohort of the 1+2+3 VXM01 titration design completed at least day 14 without any dose-limiting toxic effects (DLTs) and after confirmatory recommendation of the DSMB. Patients were confined in the study site up to day 10. The 38-d double-blind study phase has been followed by an open-label follow-up for up to 2 y.

Hematology, biochemistry, coagulation, and urine values were assessed daily up to day 10, and at the visits on day 38 and month 3. Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the National Cancer Institute's CTCAE criteria (version 4.03).28 DLTs were defined as any AEs related to study drug of grade 4 or higher, or grade 3 or higher for gastrointestinal fistula, diarrhea, gastrointestinal perforation, multi-organ failure, anaphylaxis, any auto-immune disorder, cytokine-release syndrome, intestinal bleeding, renal failure, proteinuria, thromboembolic events, stroke, heart failure, or vasculitis. In addition to standard AE reporting, VXM01 distribution and shedding was investigated in blood, saliva, tears, urine and stool samples on days 0, 2, 4, and 8.

Anti-carrier antibodies (anti-LPS IgG) and anti-VEGFR-2 antibodies (IgG and IgM) were analyzed by enzyme-linked immuno sorbent assay (ELISA) according to GLP regulations on days 0, 10, 38, and month 3 by Aurigon, Tutzing (Germany).

Analysis of T cell response

Sample handling

Immunmonitoring of T cell responses was performed on freshly isolated PBMCs on days 0, 4, 10, 14, 21, 38, and after 3 mo. Whole blood was obtained by venipuncture using EDTA- blood collection tubes and transported under ambient conditions to the NCT laboratory. Blood processing using density gradient centrifugation (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) in 50 mL Falcon tubes (Falcon, Becton Dickinson (BD), Heidelberg, Germany) filled with 18 mL blood and 15 mL RPMI Media (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany) was performed within a maximum of 6 h after venipuncture. The average cell yield per ml whole blood was 1.0 × 106 PBMCs, determined with trypan blue (Sigma) by manual count. Cells were either shipped to the Immunmonitoring laboratory for Elispot and Treg Specificity Assay or cryopreserved for patient batched Flow Cytometry Analysis. PBMCs (1 × 107 cells/mL/aliquot) were cryopreserved using freezing media containing FCS 80%, 10% X-Vivo20 (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) and 10% DMSO (Sigma). Pre-testing of FCS was performed using two different donors for PBMC cell culture test. Using Mr. frosty slow freezing containers (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, US), cells were placed in −80°C freezer for 24 h and then shipped to the Liquid nitrogen container for long term storage. For analysis PBMCs were thawed and immediately transferred to RPMI Media supplemented with Benzonase (50U, Speed Biosystems, Rockville, US) for two washing steps. Average cell viability after overnight rest in X-Vivo20 medium was >85% and mean cell yield was 50%.

Generation of dendritic cells

Generation of dendritic cells was conducted as described earlier with modifications.29 In brief, freshly isolated PBMCs were cultured in cell culture treated plates (TPP, Trasadingen, Switzerland) for 1–2 h. Non-adherent cells were washed off and cultured in X-VIVO 20 medium (Lonza) supplemented with 100 U/mL IL-2 and 60 U/mL IL-4 (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). For dendritic cell generation adherent cells were cultured with 560 U/mL recombinant human GM-CSF and 500 U/mL IL-4 (Miltenyi). After 7 d of cell culture, cells were cultured in cytokine free media (X-Vivo20) for 24 h and purified. Dendritic cells were enriched by negative selection using the Pan Mouse IgG Dynabeads® (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany), coupled to mouse anti-human CD3, CD19 (both LifeTechnology, Oslo, Norway), and CD56 (clone: C218, Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany) antibodies, respectively. T cell purification was performed using the Untouched™ Human T Cells system (Invitrogen).

Elispot IFNγ release assay

The assessment of antigen specific IFNγ secreting T cells was conducted as previously described with modifications.21 In brief, pre-coated ELISPOT plates (MAHA S4510. Millipore, Ireland) (1 μg antibody/well mAb anti IFNγ antibody clone 1-D1K Mabtech, Nackastrand, Sweden), incubated over night at 4°C; then washed and blocked with RPMI+10% AB Serum for 1 h) were filled with 2 × 104 dendritic cells/100 μL/well in triplicate wells. DCs were then loaded with 10 μg/mL VEGFR peptide pools (Proimmune, Oxford, UK) or human IgG (Sandoglobulin, CSL Behring, Bern, Switzerland) as negative control and CMV/AdV as positive control (CMV pp65; AdV5, Miltenyi Biotec) respectively. After 14 h of pulsing, 1 × 105 purified T cells were added for a 40 h DC/ TC co-culture. IFNγ secreting T cells were visualized using an enzyme-coupled detection antibody system (mAb anti-IFNγ antibody clone 7_B6-1 biotin (1:1000), Mabtech; Streptavidin ALP (1:1000), Mabtech). After each incubation time several washing steps were performed using PBS plus Tween 0.05% (BD) and PBS. For the final substrate reaction (NCT/BCIP Substrate Kit, BioRad, München, Germany) the plate was covered from light and checked for spots after 1 min and every 5 min for development of spots. Plates were analyzed using an automated Elispot reader and ImmunoSpot V 5.0.9. Smart Count Software (CTL, Bonn, Germany). The following Counting Parameters are used as default setting. Size 100%, size count: normal, Max size: 9.6250 sqmm; Min size: 0.0051 sqmm , Spot Separation: 3; Diffuse processing: normal Background balance: 0–80.

T cell response criteria and grading

An individual T effector cell response against VEGFR2 was defined positive when test peptide wells had at least two-fold higher spot counts compared to the negative control and the difference of the triplicates was significant in the unpaired two-tailed student's t-test. The strength of the VEGFR2-specific T cell response after vaccination was graded for each time point in patients matching the acceptance criterion of a minimum mean of 10 IFNγ spots/well at d0 according to the following rule: Grade 0: non-significant difference between test wells and negative control wells or no increased difference of absolute spot numbers in test and negative control wells compared to d0; grade I-III: significant difference between test and control wells and increased difference of absolute spot numbers in test and negative control wells compared to d0 <3-fold (grade I), >3 < 5 fold (grade II), >5-fold (grade III) 30. Grading definition criteria were pre-defined in statistical analysis plan.

Cytokine Catch Assay

The cytokine catch assay was performed as patient batch analysis on frozen PBMCs using IL-2, TNFα, and IFNγ secretion assay detection kits (Miltenyi) according to the manufacturer's instruction with some modifications. For DC generation pooled adherent cells of all patient time points were processed as described above. Non-adherent PBMCs were cultured for each individual time point. For pulsing of dendritic cells purified DCs were added to a 96-well plate and incubated with 10 μg/mL VEGFR2 peptide pools for 4 h. Then purified T cells are added in DC:TC ratio of 1:10 for 12 h co-culture. Cells were washed and blocked (for 10 min on ice) to prevent unspecific binding via Fc-receptors using 1.5 mg/mL human IgG (Kiovig, Baxter, Vienna, Austria) and labeled with catch reagent according to manufacturer's instructions. The cytokine secretion time was performed in X-VIVO20 media for 1.5 h. live dead cell staining was thereafter performed using the LIVE/DEAD® Fixable Yellow Dead Cell Stain (Life Technologies GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany; 1:1000), followed by labeling with IL-2-PE, IFNγ-FITC and TNF-α-APC detection antibody according to manufacturer's instructions. For exclusion of unspecific cytokine background staining, control samples were stained without the catch antibody. T cell surface staining was performed using CD4+ (PerCP-Cy5.5, 50 μg/mL, clones RPA-T4 BD PharMingen, Heidelberg, Germany, CD8+ (V450, 100 μg/ml, clone RTP-T8 BD PharMingen), CD45RO (APC-H7, 100 μg/mL, clone: UCL1, BD), CD45RA (Pe-Cy7, 50 μg/mL, clone HI100, eBiosciences, San Diego, US). Sample acquisition was done using BD FACS Canto II Flow cytometer (BD). The PMT voltages were adjusted for each fluorescence channel using unstained cells and compensations were set using a mixture of anti-mouse Ig/negative control beads (BD). Final analysis was performed on Flow Jo Software V7.6.5. (FlowJo, Ashland, US). Gating was performed excluding duplets and dead cells.

Assessment of VEGFR2 specific Treg response

Antigen specific Treg responses were determined by a functional assay as previously described11 with modifications. Briefly, 5 × 103 dendritic cells were pulsed with 10 μg/mL test peptide, human IgG and MUC-1 antigen in triplicates. T cells were purified (Untouched™ Human T Cells system, Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany), thereafter T regulatory cells were isolated in a two-step positive and negative selection from TC using Miltenyi Human Treg Isolation Kit according to manufacturer's instructions. 2.5 × 104 Tregs were co-cultured with pulsed DCs. In parallel purified T cells were plated on an anti-CD3 pre-coated plate (1:1000, clone: Okt3, orthoclone, Jansen-Silag, Rockford, US) for CD3 stimulation for 14 h. 2.5 × 104 T cells/well were then added to the DCs and Tregs for 72 h co-incubation. To assess the proliferative capacity 3H-Thymidine (1 μCi/well) was added and incorporation measured after 24 h using the liquid scintillation counter 1450 MicroBeta (PerkinElmer, Waltham Massachusetts, USA). Treg suppression was measured as (%) reduction of proliferation (measured as cpm thymidin uptake) compared to IgG negative control.

Antigens

As test antigens: 20-mer, 10 amino acids (aa) overlapping synthetic peptides derived from VEGFR2 peptide # 1–135 (omitting #21+22+76+77) and MUC1 tandem repeat (# 136–156 (x5) (both Proimmune, Oxford, UK) were used. As positive control Cytomegalovirus peptides 15-mer sequences with 11 aa overlap covering the complete sequence of pp65 protein (CMV pp56 PepTivator (CMV strainAD169)) and human adenovirus 5 (AdV-5), a pool of 15-mer (11 aa overlapping) peptides covering the complete sequence of the hexon protein of human adenovirus 5 were used. Human IgG whole protein, Sandoglobulin, served as negative control. As additional assay control a staphylococcus enterotoxin B stimulated well was added to each test.

Flow cytometry

Flow Cytometry analysis of T regulatory cells was performed as patient batch analysis on frozen PBMCs. 5 × 105 cells/ well were incubated with human IgG, for Fc-receptors blocking (1.5 mg/mL human IgG, Kiovig, Baxter). For dead cell exclusion LIVE/DEAD Fixable Yellow Dead Cell Stain (Life Technologies GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany; 1:1000) was performed followed by surface staining with CD25 V450, Clone: M-A251; CD4 PerCP Cy5.5, Clone: RPA-T4, CD3-PE, clone UCHT1, and CD127 FITC, clone: HIL-7R-M21 (all from BD).

For Foxp3 APC (Clone: 236A/E7, eBioscience, San Diego, US) intracellular staining the Fix Perm Kit and the Fix Perm Buffer (eBiosciences) was used. Respective Isotype controls or FMOs were used for staining accordingly (FITC Mouse IgG1 Isotype control; APC Mouse IgG1 Isotype control; V450 Mouse IgG1 Isotype control, all from BD). Sample acquisition was done after overnight fixation of cells using BD FACS Canto II Flow cytometer. The PMT voltages were adjusted for each fluorescence channel using unstained cells and compensations were set using a mixture of anti-mouse Ig/negative control beads (BD). Final analysis was done on Flow Jo Software V7.6.5. Gating was performed excluding duplets and dead cells. For CD25, CD127, and FoxP3 gates were set according to isotype control or FMO.

General laboratory operations, procedure standardization, assay qualification

The laboratory has not fully established GCLP conditions. Sample reception, PBMC processing, PBMC slow freezing for long-term storage, thawing of PBMCs and cell counting were performed according to established laboratory protocols which were then approved as standard operation procedures. Elispot, Treg Specificity, and Flow Cytometry Assays were performed according to established laboratory protocols. The study was performed using general research investigative but pretested assays. Raw data can be provided per request.

Analysis of tumor perfusion

Dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI)31,32 was performed on a 1.5 Tesla System (Siemens Avanto, Erlangen, Germany) system at day 0, day 38, and month 3, to assess tumor perfusion and to monitor disease status (month 3). Reading was performed as a consensus reading of two trained and experienced radiologists (5 y and more than 15 y experience), which were blinded to the treatment assignment. Tumor response was assessed by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST; version 1.0) after 3 mo. Disease status was confirmed by a second reading.

Assessment of angiostatic biomarkers

Serum levels of Collagen IV and VEGF-A were analyzed by commercial ELISA assays (Quantikine Human VEGF A Immunoassay; DVE00, R&D Systems GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany and Human Collagen IV ELISA, Serum, KT-035; KAMIYA BIOMEDICAL COMPANY, Seattle, US, respectively) according to GLP regulations on days 0, 10, 38, and month 3 by Aurigon, Tutzing, Germany.

Statistical analysis

Two-sided student's t-test was used (i) to assess the statistical significance of differences between mean spot numbers in Elispot test wells over negative control wells, (ii) to assess the significance of differences between VEGFR2 specific T cell responses in vaccinated patients compared to placebo treated patients and (iii) for assessment of differences between preexisting VEGFR2 specific T cell responses in patients responding or not responding to the vaccine by reduced tumor perfusion. Statistical significance of the reduction of Ktrans levels between d0 and d38 was calculated by wilcoxon test.

Conflicts of Interest

HSW, PB, MWB, AGN, and WEH are advisors to VAXIMM AG. HL is an officer of VAXIMM GmbH, and AGN, HL, and MS own stock options of VAXIMM AG. KB is a director of VAXIMM AG. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributors

FHSW, AGN, NH, TF, HL, MS, KB, GM, FP, UK,MD, CL, SS, LS, AVK, RK, PK, TS, WEH, LG, and PB were involved in the study conception and design, provision of study materials or patients, collection and assembly of data, data analysis, and interpretation, manuscript writing, and manuscript approval. MWB, JW, AU, and CS were involved in provision of study materials or patients, collection and assembly of data, and manuscript approval. YG, MB, SS, and LP were involved in collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and manuscript approval.

Acknowledgments

DSMB Members: Andreas Engert, Department for Internal Medicine, Colon, Germany; Christoph Huber, Immunology Cluster of Excellence, Mainz, Germany; Meinhard Kieser, Medical Biometry and Informatics, Heidelberg, Germany. SAE and trial management: The Coordination Centre for Clinical Trials (KKS) Heidelberg. Preliminary results of this trial were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting 2013.

Funding

Vaximm. VAXIMM AG provided the study drug and funding for the conduct of the study.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1. Xiang R, Luo Y, Niethammer AG, Reisfeld RA. Oral DNA vaccines target the tumor vasculature and microenvironment and suppress tumor growth and metastasis. Immunol Rev 2008; 222:117-28; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fraser A, Paul M, Goldberg E, Acosta CJ, Leibovici L. Typhoid fever vaccines: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Vaccine 2007; 25:7848-57; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shibuya M. Vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor system: physiological functions in angiogenesis and pathological roles in various diseases. J Biochem 2013; 153:13-9; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jb/mvs136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bruce D, Tan PH. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptors and the therapeutic targeting of angiogenesis in cancer: where do we go from here? Cell Commun Adhes 2011; 18:85-103; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/15419061.2011.619673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sennino B, McDonald DM. Controlling escape from angiogenesis inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12:699-709; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc3366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spratlin J. Ramucirumab (IMC-1121B): Monoclonal antibody inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. Curr Oncol Rep 2011; 13:97-102; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11912-010-0149-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Niethammer AG, Lubenau H, Mikus G, Knebel P, Hohmann N, Leowardi C, Beckhove P, Akhisaroglu M, Ge Y, Springer M, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled first in human study to investigate an oral vaccine aimed to elicit an immune reaction against the VEGF-Receptor 2 in patients with stage IV and locally advanced pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer 2012; 12:361; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2407-12-361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Niethammer AG, Xiang R, Becker JC, Wodrich H, Pertl U, Karsten G, Eliceiri BP, Reisfeld RA. A DNA vaccine against VEGF receptor 2 prevents effective angiogenesis and inhibits tumor growth. Nat Med 2002; 8:1369-75; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm1202-794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berinstein NL, Karkada M, Morse MA, Nemunaitis JJ, Chatta G, Kaufman H, Odunsi K, Nigam R, Sammatur L, MacDonald LD, et al. First-in-man application of a novel therapeutic cancer vaccine formulation with the capacity to induce multi-functional T cell responses in ovarian, breast and prostate cancer patients. J Transl Med 2012; 10:156; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1479-5876-10-156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seder RA, Darrah PA, Roederer M. T-cell quality in memory and protection: implications for vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8:247-58; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri2274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bonertz A, Weitz J, Pietsch DH, Rahbari NN, Schlude C, Ge Y, Juenger S, Vlodavsky I, Khazaie K, Jaeger D, et al. Antigen-specific Tregs control T cell responses against a limited repertoire of tumor antigens in patients with colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:3311-21; PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jain RK, Duda DG, Willett CG, Sahani DV, Zhu AX, Loeffler JS, Batchelor TT, Sorensen AG. Biomarkers of response and resistance to antiangiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2009; 6:327-38; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Verheul HM, Pinedo HM. Possible molecular mechanisms involved in the toxicity of angiogenesis inhibition. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7:475-85; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kleeff J, Beckhove P, Esposito I, Herzig S, Huber PE, Lohr JM, Friess H. Pancreatic cancer microenvironment. Int J Cancer 2007; 121:699-705; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.22871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Klug F, Prakash H, Huber PE, Seibel T, Bender N, Halama N, Pfirschke C, Voss RH, Timke C, Umansky L. Low-dose irradiation programs macrophage differentiation to an iNOS(+)/M1 phenotype that orchestrates effective T cell immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2013; 24:589-602; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, Volk C, Z'Graggen K, Galindo L, Nummer D, Ziouta Y, Bucur M, Weitz J, Schirrmacher V, Büchler MW, Beckhove P. High frequencies of functional tumor-reactive T cells in bone marrow and blood of pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Res 2005; 65:10079-87; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sommerfeldt N, Schutz F, Sohn C, Forster J, Schirrmacher V, Beckhove P. The shaping of a polyvalent and highly individual T-cell repertoire in the bone marrow of breast cancer patients. Cancer Res 2006; 66:8258-65; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weide B, Zelba H, Derhovanessian E, Pflugfelder A, Eigentler TK, Di Giacomo AM, Maio M, Aarntzen EH, de Vries IJ, Sucker A, et al. Functional T cells targeting NY-ESO-1 or Melan-A are predictive for survival of patients with distant melanoma metastasis. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:1835-41; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.2271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feuerer M, Beckhove P, Bai L, Solomayer EF, Bastert G, Diel IJ, Pedain C, Oberniedermayr M, Schirrmacher V, Umansky V. Therapy of human tumors in NOD/SCID mice with patient-derived reactivated memory T cells from bone marrow. Nat Med 2001; 7:452-8; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/86523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beckhove P, Feuerer M, Dolenc M, Schuetz F, Choi C, Sommerfeldt N, Schwendemann J, Ehlert K, Altevogt P, Bastert G, et al. Specifically activated memory T cell subsets from cancer patients recognize and reject xenotransplanted autologous tumors. J Clin Invest 2004; 114:67-76; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI200420278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Domschke C, Schuetz F, Ge Y, Seibel T, Falk C, Brors B, Vlodavsky I, Sommerfeldt N, Sinn HP, Kühnle MC, et al. Intratumoral cytokines and tumor cell biology determine spontaneous breast cancer-specific immune responses and their correlation to prognosis. Cancer Res 2009; 69:8420-8; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schuetz F, Ehlert K, Ge Y, Schneeweiss A, Rom J, Inzkirweli N, Sohn C, Schirrmacher V, Beckhove P. Treatment of advanced metastasized breast cancer with bone marrow-derived tumour-reactive memory T cells: a pilot clinical study. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2009; 58:887-900; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-008-0605-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schirrmacher V, Feuerer M, Fournier P, Ahlert T, Umansky V, Beckhove P. T-cell priming in bone marrow: the potential for long-lasting protective anti-tumor immunity. Trends Mol Med 2003; 9:526-34; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molmed.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sommerfeldt N, Beckhove P, Ge Y, Schutz F, Choi C, Bucur M, Domschke C, Sohn C, Schneeweis A, Rom J, et al. Heparanase: a new metastasis-associated antigen recognized in breast cancer patients by spontaneously induced memory T lymphocytes. Cancer Res 2006; 66:7716-23; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nummer D, Suri-Payer E, Schmitz-Winnenthal H, Bonertz A, Galindo L, Antolovich D, Koch M, Büchler M, Weitz J, Schirrmacher V, et al. Role of tumor endothelium in CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell infiltration of human pancreatic carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007; 99:1188-99; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jnci/djm064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meijerink MR, van Cruijsen H, Hoekman K, Kater M, van Schaik C, van Waesberghe JH, Giaccone G, Manoliu RA. The use of perfusion CT for the evaluation of therapy combining AZD2171 with gefitinib in cancer patients. Eur Radiol 2007; 17:1700-13; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00330-006-0425-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Van Cutsem E, Vervenne WL, Bennouna J, Humblet Y, Gill S, Van Laethem JL, Verslype C, Scheithauer W, Shang A, Cosaert J. Phase III trial of bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:2231-7; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Okamoto I, Arao T, Miyazaki M, Satoh T, Okamoto K, Tsunoda T, Nishio K, Nakagawa K. Clinical phase I study of elpamotide, a peptide vaccine for vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Sci 2012; 103:2135-8; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/cas.12014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ge Y, Domschke C, Stoiber N, Schott S, Heil J, Rom J, Blumenstein M, Thum J, Sohn C, Schneeweiss A, et al. Metronomic cyclophosphamide treatment in metastasized breast cancer patients: immunological effects and clinical outcome. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012; 61:353-62; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-011-1106-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Janetzki S, Britten CM, Kalos M, Levitsky HI, Maecker HT, Melief CJ, Old LJ, Romero P, Hoos A, Davis MM. "MIATA"-minimal information about T cell assays. Immunity 2009; 31:527-8; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim SH, Lee JM, Gupta SN, Han JK, Choi BI. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI to evaluate the therapeutic response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging 2014; 40:730-7; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jmri.24387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weber MA, Henze M, Tuttenberg J, Stieltjes B, Meissner M, Zimmer F, Burkholder I, Kroll A, Combs SE, Vogt-Schaden M, et al. Biopsy targeting gliomas: do functional imaging techniques identify similar target areas? Invest Radiol 2010; 45:755-68; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181ec9db0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.