Abstract

Gastric cancer has a high incidence and mortality rate worldwide; however, the use of biomarkers for its clinical diagnosis remains limited. The microRNAs (miRNAs) are biomarkers with the potential to identify the risk and prognosis as well as therapeutic targets. We performed the ultradeep miRnomes sequencing of gastric adenocarcinoma and gastric antrum without tumor samples. We observed that a small set of those samples were responsible for approximately 80% of the total miRNAs expression, which might represent a miRNA tissue signature. Additionally, we identified seven miRNAs exhibiting significant differences, and, of these, hsa-miR-135b and hsa-miR-29c were able to discriminate antrum without tumor from gastric cancer regardless of the histological type. These findings were validated by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. The results revealed that hsa-miR-135b and hsa-miR-29c are potential gastric adenocarcinoma occurrence biomarkers with the ability to identify individuals at a higher risk of developing this cancer, and could even be used as therapeutic targets to allow individualized clinical management.

Keywords: gastric cancer, miRnome, biomarkers, NGS

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fourth most common malignant tumor worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer mortality. Over 70% of cases occur in developing countries, such as Brazil.1 In 2012, it is estimated that there will be 20,090 new cases of stomach cancer in Brazil.1 The State of Pará, in northern Brazil, has mortality rates that are above the national average,2 and its capital, Belém, is among the capitals with the highest number of cases per capita in the world.3 Although statistical data show a decline in the incidence of GC in developed countries, the global rate of the mean cumulative survival 5 years after diagnosis is estimated at approximately 21%.4

Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of GC and represents approximately 95% of all cases.5 The most commonly used classification in Western countries is based on the studies of Lauren,6 dividing gastric adenocarcinomas into two major subtypes: diffuse and intestinal. These subtypes feature different morphology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical behavior.7 There are several etiological factors associated with the development of GC, especially bacterium Helicobacter pylori infection, poorly preserved food ingestion,8 genetics, and epigenetics factors.9

The identification of biomarkers indicative of cancer risk and prognoses would increase the ability to predict the behavior of tumors and would establish more accurate therapeutic approaches.10 Cancer research emphasizes the identification of biomarkers capable of selecting high-risk populations and other potential therapeutic targets. These biomarkers include miRNA expression profiles11,12 that are potentially useful to the detection and monitoring of tumors including GC. The potential biomarkers exhibit the appropriate biomarker characteristics, such as high sensitivity, robustness, reproducibility, specificity, and possible clinical use by minimally invasive means.13

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are more resistant to degradation than messenger RNA (mRNA) and can be detected in fresh, fixed, or frozen tissue samples and in the peripheral blood. They can also contribute to personalized treatment because they are linked to polymorphisms of different populations or individuals.14

Over 2,200 miRNAs have been identified in humans, which may regulate more than 60% of protein-coding genes. A single miRNA can pair with multiple mRNA targets and still be targeted by other miRNAs. They are characterized by variable expression in cells and tissues, which is influenced by differences in the cellular stage and stress. miRNAs also behave as central regulatory molecules in the mechanisms of ontogenesis, differentiation, carcinogenesis, and immune response.15

Improved understanding of miRNAs in GC could lead to novel prevention strategies, early detection, and improved therapeutics. Data from the literature indicate different expression levels of several miRNAs in GC.16–20 Studies have reported consistently the oncogenic activity of miR-21 by suppressing the expression of PTEN or PDCD4.21,22 Furthermore, miR-21 upregulation has been associated with lymph node metastasis in GC patients.23 miR-106b was also consistently reported as an upregulated miRNA in GC and associated with lymph node metastasis.24,25 Recently, Shiotani et al.26 suggested that the combination miR-106b with miR-21 may provide a novel and stable marker of increased risk for early GC after H. pylori eradication.

These results suggest that miRNAs may have clinical applications in the management of GC, in the assessment of the risk of recurrence and/or metastasis, and in the therapeutic strategy.27–30 However, the preliminary miRNA expression results must be confirmed and consolidated prior to their clinical applicability. It was observed that the miRNA signatures in GC differ among the various published studies; thus, the same miRNA may exhibit contrasting results. The authors must advise caution about the experimental conditions, such as sensitivity and specificity of the miRNA detection methods and, consequently, the reliability, validity, and interpretation of the signatures.31,32

The identification of a signature that can define candidate miRNAs requires a comprehensive and systematic approach to the expression profiles and functions of these elements.15 In 2010, the specific and differentiated profile of the miRnome from normal cardia gastric tissue was demonstrated for the first time by ultradeep sequencing.11 In 2014, the miRNA expression profile for the human gastric antrum region using ultradeep sequencing was revealed.12

Aiming to providing more information on the expression pattern of GC-associated miRNAs in different samples of GC, we performed the miRnome ultradeep sequencing of four GC adenocarcinoma samples and one sample of gastric antrum without tumor. The findings were validated in additional samples of tumors and nontumor gastric tissues by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR).

Methods

Biological material

Five fresh tissue samples obtained from surgical dissection were investigated by ultradeep sequencing: four samples of GC (T1N0, T1N1, T4N1 intestinal type, and T1N0 diffuse type) and one sample from the antrum of a patient without GC.12 The samples were collected from patients treated at the João de Barros Barreto Hospital/ Federal University of Pará, Brazil. Immediately after resection, the surgical specimens were analyzed by a pathologist, and a fragment from each sample was selected for the experiment in parallel with routine histological evaluation. These samples were frozen at −170 °C and stored separately in liquid nitrogen, according to the standard procedure, for subsequent miRNA extraction.

For miRNA qRT-PCR validation, 11 samples of tumor gastric and 11 gastric tissues without cancer were used. All 22 samples were collected using paraffin blocks from patients treated at the João de Barros Barreto Hospital.

Clinical data collection

Clinical and anatomopathological patient data were obtained directly from the records using the Lauren histological classification and staging according to the classification of the 7th edition of the pathological TNM staging (UICC/International Union Against Cancer).

Ethics statement

The ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the João Barros Barreto University Hospital (Protocol number 14052004/HUJBB).

SOLiD ultradeep sequencing

The SOLiD (version 4.0 plus) sequencing system (Life Technologies) was used to generate reads that were 35 bp long. In the second step, the barcodes were decoded to match each read sequence with the identity of the sample. The small RNA sequence data from the gastric tissue without cancer are available at the European Nucleotide Archive under accession number ERP004687, and the sequences from the four GC tissues are available under accession number ERP007267. EPR004687 was previously analyzed.12 The read datasets were approximately 1.1 million reads with 19% of bases at QV >20 for barcode 4; 31.2 million and 30% of bases at QV >20 for barcode 6; 22.1 million reads with 18.8% of bases at QV >20 for barcode 7; and 35.5 million reads with 21.1% of bases at QV >20 for barcode 9. Sequence analysis was performed using the SOLiD System Small RNA Analysis Tool (Life Technologies) and a miRanalyzer.12 First, a preprocessing pipeline was used to filter out low-quality reads, to trim the 3’ ends, and to remove sequences that matched RNA contaminants, such as tRNA, rRNA, DNA repeats, and adaptor molecules. After the preprocessing steps, the reads were 25 bp in length and the percentage of bases at QV >20 was 69.8%, 78.3%, 70.1%, and 35.5% for barcode 4, barcode 6, barcode 7, and barcode 9 datasets, respectively. After excluding the contaminant reads, we aligned all of the sequences against the miRNA precursor sequences (miRBase – release 19) and included in the results only the reads that matched the mature miRNA sequences. The number of reads that were mapped uniquely and unambiguously against the mature miRNA sequences (miRBase – release 19) was 42,565, 33,665, 618,120, and 58,335 for barcodes 4, 6, 7, and 9, respectively. The coverage was analyzed based on the miR size, the percent of GC, and the expression level. The global average was approximately 628x, and the miRs of lengths 21, 22, and 23 nt had the highest sequencing coverage at approximately 1641, 4454, and 1342x, respectively. The miRs with lower size (15–20 nt) had a coverage of 3.5x and the miRs of higher size (24–27 nt) had a coverage of 22.4x. Regarding the GC content, the miRs with 30%–50% GC content had an average sequence coverage of 200x, those with 60%–70% had a GC content at 5.6x, and the other classes were lower than 2x. For describing the expression value, three levels are defined as low expressed (100 reads or lower mapped), medium expressed (100–500 reads), and highly expressed (500 or more reads). For all the miRs observed in the five conditions (control and four cancer tissues), the distribution was 348 miRs at the low level, 49 at the medium level, and 40 at the high level. For further comparison, the expression value of each miR was normalized (RPKM).

miRNA qRT-PCR (validation)

To extract the miRNAs from each sample, a high purity miRNA isolation Kit (Roche) was used. The solutions were quantified using the Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen) and diluted to a final concentration of 4 ng/μL. Then, the cDNA was obtained using TaqMan® MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies), and the Quantitative Real-Time PCR reaction was performed using the TaqMan® MicroRNA Assays in a 7500 Real Time PCR system (Life Technologies) with TaqMan miRNA assays according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies) using primers designed by Primer Express (Life Technologies). The mean expression level of three human endogenous controls (Z30, RNU19 and RNU6B – calibrators) was used as an internal control in all of the miRNA experiments to allow the comparison of expression results. The relative miRNA expression levels were then calculated by a comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method (2−Δct).

Data analysis

Before performing the differential analysis on the SOLiD sequence data, the miRNAs with low expression (<10 reads) were filtered out. Then, the betaBin model33 was used. The miRNA count was normalized (RPKM), and the fold change was obtained for each miRNA comparison. The miRNAs were tagged as differentially expressed if they met the following criteria: (i) a minimum of 10 reads mapped per miRNA in at least one sample; (ii) a P-value <0.0002 after a Bonferroni correction to the multiple testing problem34–36; and (iii) an expression greater than a fivefold change (>5 or <0.2).37 The result is presented as a volcano plot. In addition, a heat map was created using the normalized log10 miRNA expression value. For the above analyses, the R statistical environment (http://www.r-project.org/) was used.

The qRT-PCR, statistical analyses were performed in the SPSS v.12 software, using a paired Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test, considering a P-value of <0.01 for statistically significant results.

Results

The total read counts for the different tissues were as follows: (i) 31 million reads in the intestinal T1N0 GC; (ii) 22 million reads in the intestinal T1N1 GC; (iii) 1 million reads in the intestinal T4N1 GC; (iv) 35 million reads in the diffuse T1N0 GC; and (v) 618 thousand reads in the antrum without tumor tissue.12

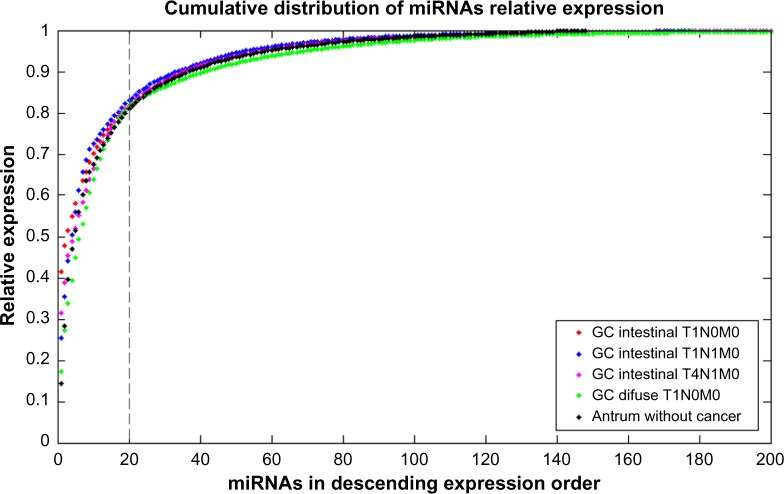

The total mature miRNAs were as follows: (i) 245 mature miRNAs in the intestinal T1N0 GC; (ii) 410 mature miRNAs in the intestinal T1N1 GC; (iii) 253 mature miRNAs in the intestinal T4N1 GC; (iv) 372 mature miRNAs in the diffuse T1N0 GC; and (v) 148 mature miRNAs in the antrum without cancer tissue.12 Figure 1 shows the cumulative distribution of the miRNA relative expression in descending order for all tissues sequenced.

Figure 1.

Cumulative distribution of the miRNA relative expression for all tissues sequenced, in descending order of miRNA expression. Twenty miRNAs (highlighted line) were responsible for approximately 80% of the total miRNAs expression.

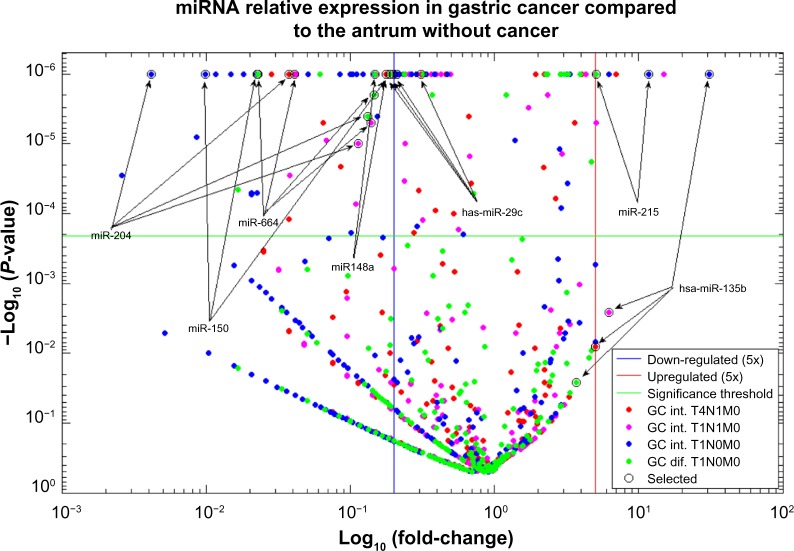

Several mature miRNAs exhibiting statistically significant expression differences even after Bonferroni correction to the multiple testing problem (P < 0.0002 and fold changes >5 or <0.02) were found among the GC tissues when compared with the antrum without cancer tissue (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Relative expression profile of miRNAs in GC tissues compared to the healthy tissue expression.

The miRNA hsa-miR-29c was able to discriminate normal antrum from GC tissue because it was differentially expressed in every tumor sample compared to the antrum sample without tumor. These results were validated by qRT-PCR.

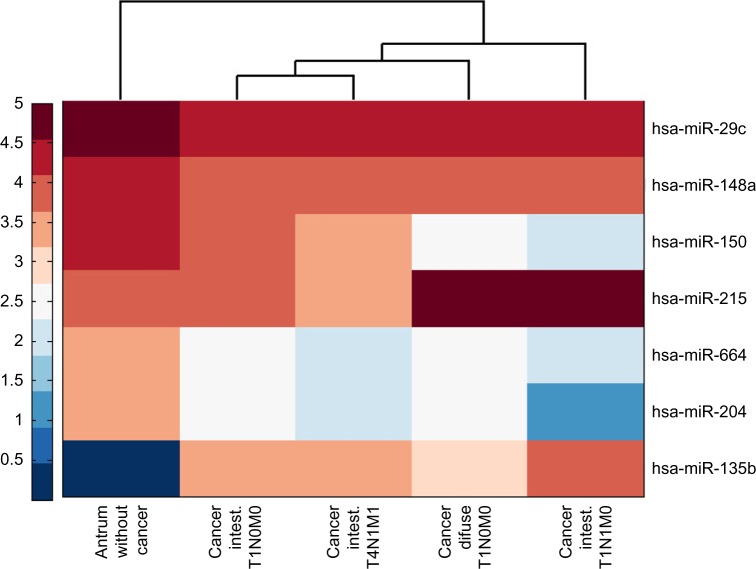

Additionally, we identified other highly expressed miRNAs such as has-miR-135 and hsa-mir-215, which were significantly upregulated, and miRNAs hsa-mir-204, hsa-mir-664, hsa-mir-150I, and hsa-mir-148a, which were found to be downregulated (Table 1). Figure 3 shows a heat map comparing the normalized expression of all the selected miRNAs.

Table 1.

miRNAs differentially expressed in at least two gastric cancer samples, normalized in reads per million.

| miRNA | ANTRUM | INTESTINAL | DIFUSE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1N0M0 | T1N1M0 | T4N1M0 | T1N0M0 | ||

| hsa-mir-135b | 0 | 1,931 | 9,692 | 1,551 | – |

| hsa-mir-215 | 7,230 | – | 87,996 | – | 38,132 |

| hsa-mir-204 | 2,829 | 327 | 11 | 94 | 406 |

| hsa-mir-664a | 3,144 | 446 | 76 | 117 | 500 |

| hsa-mir-150 | 12,575 | 4,456 | 125 | 2,232 | 287 |

| hsa-mir-148a | 34,266 | – | – | 6,038 | 5,116 |

| hsa-mir-29c | 112,858 | 22,308 | 23,803 | 34,723 | 21,210 |

Note: Cells with a (–) value indicate that no significant difference in expression between the samples and the control sample were found.

Figure 3.

Heat map of log10 normalized expression (RPKM) of differentiated expressed miRNAs in human gastric cancer tissue compared to the antrum without cancer tissue.

To elucidate the possible pathways of the miRNAs described, data from both the TargetScan dataset38 and microRNA.org39 were used by the targetCompare40 tool to identify simultaneous putative target genes. Table 2 presents 13 putative genes that are simultaneously targeted by up to two miRNAs that are described as downregulated in at least two GC samples.

Table 2.

Common target genes of the miRNAs that were significantly downregulated in at least two GC samples compared with a noncancer antrum tissue.

| GENES | hsa-miR-29c | hsa-miR-204 | hsa-miR-148a | hsa-miR-150 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPS15 | • | • | • | • |

| IRF2BP2 | • | • | • | • |

| MTMR4 | • | • | • | • |

| NID1 | • | • | • | • |

| PDK4 | • | • | • | • |

| PPARGC1A | • | • | • | • |

| RHOBTB1 | • | • | • | • |

| SLC39A9 | • | • | • | • |

| TP53INP1 | • | • | • | • |

| XPO5 | • | • | • | • |

| DNMT3B | • | • | ||

| SIRT1 | • | • | • | |

| PDGFRA | • | • | • |

Note: hsa-miR-664a was excluded from the table due to the absence of a predicted target in both of the datasets used.

qRT-PCR

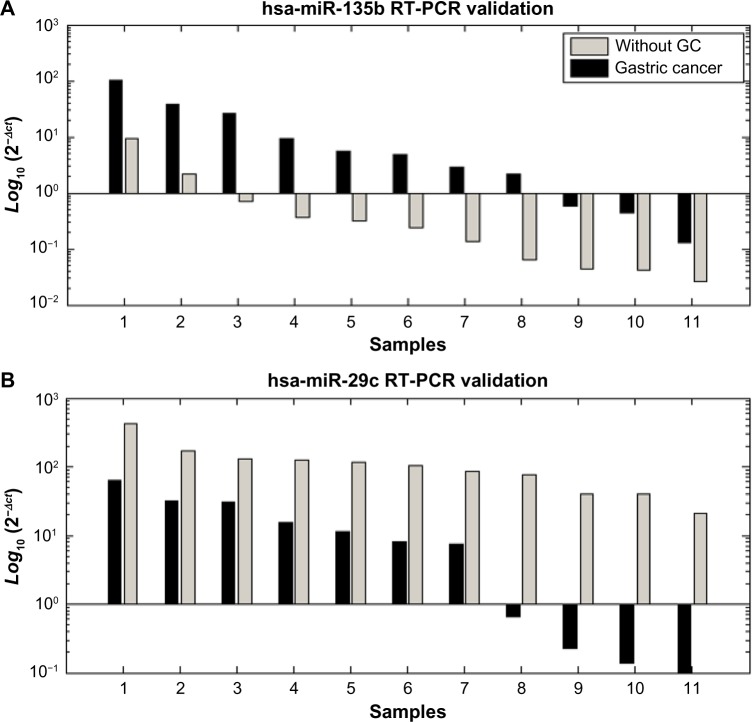

Among the selected differentially expressed miRNAs, we investigated miRNAs with higher absolute values of read counts and that already had been described in other works as differentiated in cancer. According to this criterion, hsa-miR-135b and hsa-miR-29c were selected for validation.

The high-throughput sequencing results for hsa-miR-135b and hsa-miR-29c were validated using singleplex qRT-PCR to determine their expression levels in 11 tumor gastric samples and 11 gastric tissues without cancer. The results of the 22 samples by qRT-PCR analysis confirmed the findings of both miRNAs identified as being differentiated by the SOLiD platform. They were also significantly differentiated when compared to the expression levels of endogenous Z30 (P-value < 0.001, Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Quantification of hsa-miR-135b (A) and hsa-miR-29c (B) by RT-PCR. Quantification was based on Ct values and normalized using an endogenous Z30 expression control. The 2−∆Ct represents the mean of triplicates from 22 different individual samples.

Discussion

On analyzing the relative expression for each miRNA, we found that the expressions in all GC tissues are highly concentrated in several miRNAs such that less than 20 miRNAs account for approximately 80% of the total expression (Fig. 1). This result corroborates the antrum miRnome expression profile12 and could suggest that the miRNA expression in tissues may follow a Pareto distribution, where several of the miRNAs are responsible for most of the miRNA expression in the tissue.

The expression analysis determined that miRNAs hsa-miR-29c and hsa-miR-135b were able to discriminate normal antrum from GC because they were differentially expressed in every tumor sample compared to antrum sample without tumor, regardless of the Lauren histological type.

The miRNA hsa-miR-29c was found to be downregulated in all four GC samples, regardless of the histological type (intestinal or diffuse), and these results were similar to those of other studies with GC.27,30 The RCC2 gene (also known as TD-60), regulated by hsa-miR-29c, is reported as a component of the chromosomal passenger complex, which is a crucial regulator of chromosomes, cytoskeleton, and membrane dynamics throughout mitosis.30,41 The GSTM3 gene, also regulated by hsa-miR-29c, was associated with the occurrence of GC.42

Several studies have used qRT-PCR to quantify the expression of hsa-miR-29c in association with different types of cancer development.43,44 The qRT-PCR analysis corroborated the ultradeep sequencing results, where hsa-miR-29c was downregulated in all GC samples, showing its potential as a GC molecular biomarker.

The miRNA hsa-miR-135b was expressed in all four tumors examined, and it showed no expression in the antrum without GC, suggesting that this miRNA may be related to the occurrence of GC. Wang et al demonstrated an upregulation of hsa-miR-135b in GC tissues.19 hsa-miR-135b showed higher levels of expression in colorectal cancer compared to healthy tissue. This miRNA was found to have altered expression in lung cancer and is supposed to regulate LATS2, NDR2, LZTS1, and BTRC.45 Recently, hsa-miR-135b was associated with the regulation of genes frequently mutated in colorectal cancer, including TGFRB2, DAPK1, APC, and HIC.46,47 The miR-135b was predicted as a regulator of the c-KIT gene, closely associated with the development of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs),48 and this miRNA also regulates other genes involved in cancer occurrence, such as CASP10.49,50

To obtain an integrated overview of the whole data, a simultaneous analysis of miRNAs targets was performed. This approach showed that several different genes might be regulated by up to two miRNAs described as downregulated in this investigation (Table 2). Many cellular functions are regulated by these target genes, including cell cycle control, cell motility, and cell migration, which indicates that these miRNAs may play a role in tumorigenesis.

The EPS15 gene, a putative target of all four miRNAs found as downregulated in GC, is involved in the EGFR pathway and may be useful as a prognostic marker for predicting GC behavior.51

The DNMT3B gene, regulated by hsa-miR-29c and hsa-miR-148a, has single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with a high risk of GC occurrence.52 The SIRT1 gene, a target of hsa-miR-29c, hsa-miR-204, and hsa-miR-150, is a significant prognostic indicator for GC.53 Other genes such as FCGR2A, MMP2, and PDGFRA are GC associated54–56 and may also be the targets of hsa-miR-29c, hsa-miR-148a, and hsa-miR−150.

In silico target analysis revealed that 92 genes may be regulated by both hsa-miR-135b and hsa-miR-215. Among these potential targets, we highlight the LPP gene that was found to be deregulated in several benign and malignant tumors.57 We also highlight BRWD1, which is involved in a variety of cellular functions,58 and PPM1A that encodes a protein member of the PP2C family of Ser/Thr protein phosphatases. The overexpression of this phosphatase is reported to cause diverse downstream outcomes, such as cell cycle progression, apoptosis, differentiation, and migration.59

Conclusions

The high-throughput sequencing demonstrated that a restricted set of miRNAs are responsible for the majority of the miRNA expression in GC, providing a tissue signature. Additionally, we successfully identified two potential miRNA biomarkers (miR-135b and miR-29c) validated by qRT-PCR, capable of determining the occurrence of GC. These results open up new clinical applications and may be useful in providing individualized GC management.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank André Nicolau Gonçalves and Dayse Alencar for their great help in the development of this work. Special thanks to the donors of samples, which enabled this study.

Footnotes

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Thomas Dandekar, Associate Editor

FUNDING: This work is part of the Rede de Pesquisa em Genômica Populacional Humana (BioComputacional – Protocol No. 3381/2013/CAPES). Financial support: CAPES; PROPESP/ UFPA-FADESP; MS/Decit, CNPq, FAPESPA and SESPA. Fabiano Cordeiro Moreira is supported by Pós-Doc Junior (PDJ) fellowship from CNPq/Brazil (BioComputacional – Protocol No. 3381/2013/CAPES); Ândrea Ribeiro-dos-Santos supported by CNPq/Produtividade; Sidney Santos supported by CNPq/Produtividade. The authors confirm that the funder had no influence over the study design, content of the article, or selection of this journal.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Paper subject to independent expert blind peer review by minimum of two reviewers. All editorial decisions made by independent academic editor. Upon submission manuscript was subject to anti-plagiarism scanning. Prior to publication all authors have given signed confirmation of agreement to article publication and compliance with all applicable ethical and legal requirements, including the accuracy of author and contributor information, disclosure of competing interests and funding sources, compliance with ethical requirements relating to human and animal study participants, and compliance with any copyright requirements of third parties. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: ARS, PA, AS, SS. Analyzed the data: SyD, FCM, IGH, AC, LM. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: SyD, FCM, IGH. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: RB, AK, SS, SD, MA, PA, ARS. Agreed with manuscript results and conclusions: SyD, FCM, PA, ARS. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: SyD, FCM, IGH, PA, ARS. Made critical revisions and approved final version: SyD, FCM, ARS. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brasil. Ministério da saúde Secretaria de atenção à saúde. Instituto nacional de câncer. Coordenação de prevenção e Vigilância de câncer . Estimativas 2008: incidência de câncer no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resende ALS, Mattos IE, Koifman S. Mortalidade por câncer gástrico no estado do Pará, 1980–1997. Arq Gastroenterol. 2006;43(3):247–52. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032006000300018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iarc International Agency for Research on Cancer Iarc monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2002;96:1–390. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajdev L. Treatment options for surgically resectable gastric cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2010;11:14–23. doi: 10.1007/s11864-010-0117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith MkG, Hold G-L, Tahara E, El-Omar EM. Cellular and molecular aspects of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2979–90. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i19.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so called intestinal type carcinoma: an attempt at a histo clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan F, Shukla A. Pathogenesis and treatment of gastric carcinoma: “an up-date with brief review”. J Cancer Res Ther. 2006;2:196. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.29830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moutinho V, Makino E. Epidemiological características do cancro gástrico em Belém (Brasil) Arq Bras Cir Dig. 1988;3:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasui W, Yokozaki H, Fujimoto J, Naka K, Kuniyasu H, Tahara E. Genetic and epigenetic alterations in multistep carcinogenesis of the stomach. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(suppl 12):111–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Assumpção PP, Burbano RR. Genética e câncer gástrico. In: Linhares E, Laércio L, Takeshi S, editors. Atualização em câncer gástrico. São Paulo: Tecmed; 2005. pp. 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribeiro-dos-Santos Â, Khayat AS, Silva A, et al. Ultra-deep sequencing reveals the microRNA expression pattern of the human stomach. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreira FC, Assumpção M, Hamoy IG, et al. MiRNA expression profile for the human gastric antrum region using ultra-deep sequencing. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hackenberg M, Sturm M, Langenberger D, Falcón-Pérez JM, Aransay AM. miRanalyzer: a microRNA detection and analysis tool for next-generation sequencing experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W68–76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribeiro-dos-Santos A, Cruz AMP, Darnet S. Deep sequencing of MicroRNAs in câncer: expression profiling and its application. In: Mallick B, Ghosh Z, editors. Regulatory RNAs. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 523–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmerman AL, Wu S. MicroRNAs, cancer and cancer stem cells. Cancer Lett. 2011;300:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai KW, Liao YL, Wu CW, et al. Aberrant expression of miR-196a in gastric cancers and correlation with recurrence. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51(4):394–401. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song F, Yang D, Liu B, et al. Integrated microRNA network analyses identify a poor-prognosis subtype of gastric cancer characterized by the miR-200 family. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(4):878–89. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu T, Tang H, Lang Y, Liu M, Li X. MicroRNA-27a functions as an oncogene in gastric adenocarcinoma by targeting prohibitin. Cancer Lett. 2009;273:233–42. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang M, Gu H, Wang S, et al. Circulating miR-17–5p and miR-20a: molecular markers for gastric cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5(6):1514–20. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li N, Tang B, Zhu ED, et al. Increased miR-222 in H pylori-associated gastric cancer correlated with tumor progression by promoting cancer cell proliferation and targeting RECK. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(6):722–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng Y, Cui L, Sun W, et al. MicroRNA-21 is a new marker of circulating tumor cells in gastric cancer patients Cancer Biomark 2011. –201210271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao Z, Yoon JH, Nam SW, Lee JY, Park WS. PDCD4 expression inversely correlated with miR-21 levels in gastric cancers. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:611–9. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1140-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y, Sun J, Xu J, Li Q, Guo Y, Zhang Q. miR-21 is a promising novel biomarker for lymph node metastasis in patients with gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:640168. doi: 10.1155/2012/640168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang JL, Hu Y, Kong X, et al. Candidate microRNA biomarkers in human gastric cancer: a systematic review and validation study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SY, Jeon TY, Choi CI, et al. Validation of circulating miRNA biomarkers for predicting lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15(5):661–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garzon R, Marcucci G. Potential of microRNAs for cancer diagnostics, prognostication and therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24(6):655–9. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328358522c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ueda T, Volinia S, Okumura H, et al. Relation between microRNA expression and progression and prognosis of gastric cancer: a microRNA expression analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:136–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70343-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tchernitsa O, Kasajima A, Schäfer R, et al. Systematic evaluation of the miRNA-ome and its downstream effects on mRNA expression identifies gastric cancer progression. J Pathol. 2010;222:310–9. doi: 10.1002/path.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng R, Chen X, Yu Y, et al. MiR-126 functions as a tumour suppressor in human gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2010;298:50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuo M, Nakada C, Tsukamoto Y, et al. MiR-29c is downregulated in gastric carcinomas and regulates cell proliferation by targeting RCC2. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:15. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, Yan Z, Zhang J, et al. Combination of hsa-miR-375 and hsa-miR-142–5p as a predictor for recurrence risk in gastric cancer patients following surgical resection. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2257–66. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J, Wang Q, Liu H, Hu B, Zhou W, Cheng Y. MicroRNA expression and its implication for the diagnosis and therapeutic strategies of gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2010;297:137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vêncio RZN, Brentani H, Patrão DFC, Pereira CAB. Bayesian model accounting for within-class biological variability in Serial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE) Vol. 5. BMC Bioinformatics; 2004. p. 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morin RD, O’Connor MD, Griffith M, et al. Application of massively parallel sequencing to microRNA profiling and discovery in human embryonic stem cells. Genome Res. 2008;18(4):610–21. doi: 10.1101/gr.7179508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarver AL, Li L, Subramanian S. MicroRNA miR-183 functions as an oncogene by targeting the transcription factor EGR1 and promoting tumor cell migration. Cancer Res. 2010;70(23):9570–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noble WS. How does multiple testing correction work? Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(12):1135–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1209-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon DF, Domingos RF, Hauser C, Hutchins CM, Zerges W, Wilkinson KJ. Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of the effects of metal nanoparticle exposure on the transcriptome of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(16):4774–85. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00998-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. The microRNA.org resource: targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D149–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreira FC, Dustan B, Hamoy IG, Ribeiro-Dos-Santos AM, Dos Santos AR. TargetCompare: a web interface to compare simultaneous miRNAs targets. Bioinformation. 2014;10(9):602–5. doi: 10.6026/97320630010602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skoufias DA, Mollinari C, Lacroix FB, Margolis RL. Human survivin is a kinetochore-associated passenger protein. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1575–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malik MA, Upadhyay R, Mittal RD, Zargar SA, Modi DR, Mittal B. Role of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzyme gene polymorphisms and interactions with environmental factors in susceptibility to gastric cancer in Kashmir valley. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2009;40:26–32. doi: 10.1007/s12029-009-9072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding DP, Chen ZL, Zhao XH, et al. miR-29c induces cell cycle arrest in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by modulating cyclin E expression. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1025–32. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santanam U, Zanesi N, Efanov A, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia modeled in mouse by targeted miR-29 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12210–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007186107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin CW, Chang YL, Chang YC, et al. MicroRNA-135b promotes lung cancer metastasis by regulating multiple targets in the Hippo pathway and LZTS1. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1877. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu XM, Qian JC, Deng ZL, et al. Expression of miR-21, miR-31, miR-96 and miR-135b is correlated with the clinical parameters of colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2012;4:339–45. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ng EK, Chong WW, Jin H, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in plasma of patients with colorectal cancer: a potential marker for colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2009;58:1375–81. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.167817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin-Broto J, Gutierrez A, Garcia-del-Muro X, et al. Prognostic time dependence of deletions affecting codons 557 and/or 558 of KIT gene for relapse-free survival (RFS) in localized GIST: a Spanish Group for Sarcoma Research (GEIS) Study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1552–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oh JE, Kim MS, Ahn CH, et al. Mutational analysis of CASP10 gene in colon, breast, lung and hepatocellular carcinomas. Pathology. 2010;42:73–6. doi: 10.3109/00313020903434371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kudo Y, Iizuka S, Yoshida M, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) directly and indirectly promotes tumor angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:38716–28. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.373159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galizia G, Lieto E, Orditura M, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression is associated with a worse prognosis in gastric cancer patients undergoing curative surgery. World J Surg. 2007;31:1458–68. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu J, Fan H, Liu D, Zhang S, Zhang F, Xu H. DNMT3B promoter polymorphism and risk of gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1011–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0831-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cha EJ, Noh SJ, Kwon KS, et al. Expression of DBC1 and SIRT1 is associated with poor prognosis of gastric carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4453–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xia HZ, Du WD, Wu Q, et al. E-selectin rs5361 and FCGR2 A rs1801274 variants were associated with increased risk of gastric cancer in a Chinese population. Mol Carcinog. 2012;51:597–607. doi: 10.1002/mc.20828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Partyka R, Gonciarz M, Jalowiecki P, Kokocinska D, Byrczek T. VEGF and metalloproteinase 2 (MMP 2) expression in gastric cancer tissue. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:BR130–4. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chompret A, Kannengiesser C, Barrois M, et al. PDGFRA germline mutation in a family with multiple cases of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:318–21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grunewald TG, Pasedag SM, Butt E. Cell adhesion and transcriptional activity – defining the role of the novel protooncogene LPP. Transl Oncol. 2009;2:107–16. doi: 10.1593/tlo.09112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Philipps DL, Wigglesworth K, Hartford SA, et al. The dual bromodomain and WD repeat-containing mouse protein BRWD1 is required for normal spermiogenesis and the oocyte-embryo transition. Dev Biol. 2008;317:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li R, Gong Z, Pan C, et al. Metal-dependent protein phosphatase 1A functions as an extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphatase. FEBS J. 2013;280:2700–11. doi: 10.1111/febs.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]