Abstract

Viral factor has been implicated in the etiopathogenesis of vitiligo. To elucidate the effects of viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) on melanocytes and to explore the underlying mechanisms, primary cultured normal human melanocytes were treated with synthetic viral dsRNA analog poly(I:C). The results demonstrated that poly(I:C)-triggered apoptosis when transfected into melanocytes, while extracellular poly(I:C) did not have that effect. Intracellular poly(I:C)-induced melanocyte death was decreased by RIG-I or MDA5 siRNA, but not by TLR3 siRNA. Both intracellular and extracellular poly(I:C) induced the expression of IFNB, TNF, IL6, and IL8. However, extracellular poly(I:C) demonstrated a much weaker induction capacity of cytokine genes than intracellular poly(I:C). Further analysis revealed that phosphorylation of TBK1, IRF3, IRF7, and TAK1 was differentially induced by intra- or extracellular poly(I:C). NFκB inhibitor Bay 11-7082 decreased the induction of all the cytokines by poly(I:C), suggesting the ubiquitous role of NFκB in the process. Poly(I:C) treatment also induced the phosphorylation of p38 and JNK in melanocytes. Both JNK and p38 inhibitors showed suppression on the cytokine induction by intra- or extracellular poly(I:C). However, only the JNK inhibitor decreased the intracellular poly(I:C)-induced melanocyte death. Taken together, this study provides the possible mechanism of viral factor in the pathogenesis of vitiligo.

Introduction

The color of human skin is mainly determined by the type and amount of melanin pigments deposited in the epidermis. Melanin is synthesized in specialized cellular organelles called melanosomes in epidermal melanocytes mature melanosomes loaded with melanin, which are transported from melanocytes into adjacent keratinocytes to form the skin color (Lin and Fisher, 2007). In some skin pigmentation disorders like vitiligo, the loss of skin pigmentation is caused by the destruction of epidermal melanocytes. Various mechanisms, including oxidative stress, neural factor, melanocyte degeneration, and autoimmune, have been proposed to participate in the melanocyte destruction in vitiligo lesions (Taieb and Picardo, 2009). However, the initial cause of vitiligo is still elusive.

As the outer barrier of human body, human skin has persistent contact with various pathogens. It has been demonstrated that epidermal melanocytes are important targets of viral infection (Harson and Grose, 1995). In fact, several studies have linked the pathogenesis of vitiligo to the infection of a variety of viruses, such as cytomegalovirus, hepatitis virus, and HIV (Duvic et al., 1987; Grimes et al., 1996; Tsuboi et al., 2006). However, the exact mechanism of viral infection leading to vitiligo has not been fully elucidated. Thus, understanding the impact of viral infection on the melanocyte viability and biological functions may help us to uncover the roles of viral infection in the pathogenesis of vitiligo.

When viral infection occurs, the innate immune system within infected cells recognizes pathogen-associated molecule patterns (PAMPs) and triggers a range of innate immune responses, which consist of induction of cell death and release of proinflammatory cytokines to impede the spread of pathogen. For viruses or some intracellular bacteria, the foreign nucleic acids, including double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), act as major PAMPs. In dendritic cells and other cell types, dsRNA, introduced into the cytoplasm, is recognized by DExD/H-box-containing RNA helicases, including retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 (RIG-I) and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) (Kato et al., 2008; Peisley et al., 2011). Both RIG-I and MDA5 are RIG-I like receptor (RLR) family members. They bind to the adaptor molecule IPS-1 and promote the apoptosis and expression of type I interferon genes or proinflammatory cytokine genes, for example, TNF, through a TBK-1- and IRF3-dependent pathway (Kawai et al., 2005). TAK1 and NFκB activities have also been reported to be involved in that process (Mikkelsen et al., 2009). Another dsRNA receptor that has been identified is TLR3, which belongs to the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family. TLR3 is located in the membrane of endosomes where it senses the extracellular dsRNA endocytosed by cells (Kalali et al., 2008; Chattopadhyay and Sen, 2014). TLR3 activates NFκB leading to the transcription of proinflammatory cytokines. In an alternative pathway, TLR3 activates TBK-1, which results in the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of IRF3 and IRF7 followed by the expression of IFNB and TNF genes (Jiang et al., 2004; Sankar et al., 2006). Little, however, is known about the effects of dsRNA on human melanocytes.

The aim of this study was to determine the effects of poly(I:C), a synthetic viral analog of dsRNA, on normal human melanocytes. In addition, we also investigated the receptors and signaling pathways that mediate the effects of poly(I:C).

Materials and Methods

Reagents

All culture media and supplements used for the isolation and cultivation of melanocytes were obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY) with the exception of recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX), and cholera toxin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Poly(I:C) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay Kit was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). The RNeasy Mini Kit for RNA purification, QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit, and QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR Kit were obtained from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). The TLR3 antibody was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). The β-actin antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz (Dallas, TX). Neutralizing antibodies for IFN-α, IFN-β, and TNF-α were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom). All the other antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Inhibitors, including U0126, SB203580, SP600125, and BAY 11-7082, were obtained from Beyotime (Haimen, China). Primers were synthesized at Shanghai Generay Biotech (Shanghai, China) and siRNA pools for AIM2, RIG-I, TLR3, and nontargeting control siRNA were the products of GenePharma (Shanghai, China).

Cell culture

The primary normal melanocytes were isolated from human foreskin specimens obtained after circumcision surgery. Methods for the isolation and cultivation of melanocytes were described previously (Wang et al., 2014). Cells were cultured in the Hu16 medium (F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 20 ng/mL bFGF, and 20 μg/mL IBMX). The cells were used between passages 2 and 5.

LDH release assay

Melanocytes were plated in 96-well plates at the density of 1×104 cells/well and cultured overnight before subjected to different treatments. After experiment, 50 μL of supernatants from each well of the assay plate were transferred to the corresponding well of a 96-well enzymatic assay plate and incubated with 50 μL of substrate mix for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 μL of stop solution and the absorbance was measured with a microplate spectrophotometer at 490 nm.

Annexin V-PI staining

Experimental melanocytes were detached by 0.05% trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution and resuspended in 100 μL of 1× binding buffer containing Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Then, 400 μL of 1× binding buffer were added, and the cells were analyzed immediately with a flow cytometer (BD FACScalibur, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Real-time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from melanocytes and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed to measure the mRNA levels of IFNB (forward primer: 5′-ACTGCCTCAAGGACAGGATG-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GGCCTTCAGGTAATGCAGAA-3′), TNF (forward primer: 5′-ATGTGCTCCTCACCCACACC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CCCTTCTCCAGCTGGAAGAC-3′), IL6 (forward primer: 5′-ACTCACCTCTTCAGAACGAATTG-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CCATCTTTGGAAGGTTCAGGTTG-3′), and IL8 (forward primer: 5′-ACTGAGAGTGATTGAGAGTGGAC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-AACCCTCTGCACCCAGTTTTC-3′). The expression level of each gene was normalized against β-actin (forward primer: 5′-ATAGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAACGTAC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CACCTTCTACAATGAGCTGCGTGTG-3′) using the comparative Ct method and expressed as the ratio of control, with the control as 1.

RNA silencing

Melanocytes cultured in six-well plates at a density of 2×105 cells/well were transfected with 30 nM siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were cultured for 72 h with siRNAs before receiving further treatment.

Western blotting

The proteins in the total cell lysates were separated by 10–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by transferring to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk in TBST (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with specific primary antibodies. The membrane was then washed with TBST and incubated with fluorescent dye-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. The protein immunocomplex was visualized by an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE).

Statistical analysis

Student's t-test was used to assess statistical significance. A value of p<0.05 was considered to be a significant difference. Data are expressed as the mean±SD from at least three independent experiments.

Results

Apoptosis induction by intracellular poly(I:C) in normal human melanocytes

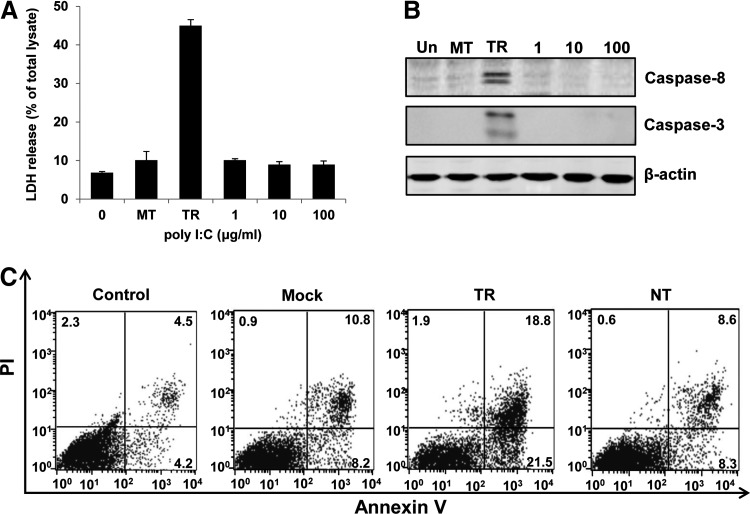

To investigate the influence of dsRNA on the viability of melanocytes, primarily cultured normal human melanocytes were transfected with poly(I:C) or treated with 1, 10, or 100 μg/mL of poly(I:C), which were added into the culture medium. Examination of LDH activity in cell culture supernatants demonstrated that poly(I:C) transfection caused significant LDH release from melanocytes in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting the induction of cell death (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/dna). Conversely, poly(I:C) did not induce LDH release even at the concentration of 100 μg/mL when added into the culture medium (Fig. 1A). Treatment with the transfection reagent (mock transfection, MT) did not cause significant cell death as well. Western blotting analysis indicated that intracellular poly(I:C) treatment induced the cleavage of caspase-8 and caspase-3 (Fig. 1B). This result suggested that intracellular poly(I:C)-caused melanocyte damage was due to apoptosis. We further quantified the apoptotic rate of melanocytes using Annexin V-PI staining. It was shown that about 40% of melanocytes went apoptosis when cells were treated with intracellular poly(I:C). Whereas extracellular poly(I:C) did not induce significant apoptosis in melanocytes (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Apoptosis induction by intracellular poly(I:C) in normal human melanocytes. Melanocytes were transfected with 1 μg/mL of poly(I:C) (TR) or treated with various concentrations of poly(I:C) (0, 1, 10, or 100 μg/mL) in the culture medium for 24 h. (A) Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) contents in the supernatants of cell culture were measured to evaluate cell death. (B) Cells were harvested and cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blotting with antibodies against cleaved Caspase-8 and Caspase-3. β-actin was probed as the loading control. (C) Melanocytes were untreated (Un), mock transfected (MT), transfected with 1 μg/mL poly(I:C) (TR), or treated with 100 μg/mL of poly(I:C) (NT) in the culture medium for 24 h. Cells were then stained with Annexin V-PI and examined by a flow cytometer. One experiment representative of three experiments. SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

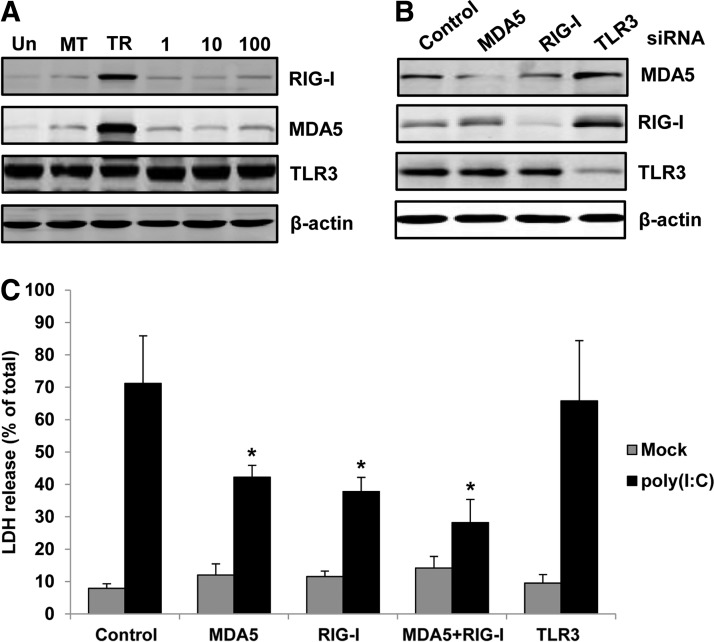

Participation of both RIG-I and MDA5 in melanocyte apoptosis triggered by intracellular poly(I:C)

It was shown that protein levels of MDA5 and RIG-I, but not TLR3, were significantly increased in melanocytes after poly(I:C) transfection. Whereas extracellular poly(I:C) treatment did not change the protein levels of those receptors (Fig. 2A). To find out which receptor mediates the apoptosis in melanocytes after poly(I:C) transfection, we knocked down the expression of MDA5, RIG-I, or TLR3 in melanocytes with siRNAs (Fig. 2B) and then measured the poly(I:C)-induced cell death by LDH release assay. It was shown that knocking down MDA5 or RIG-1 partially decreased the LDH release induced by poly(I:C) transfection. Knocking down TLR3, however, did not change the LDH release. In addition, knocking down MDA5 and RIG-I together caused a further decrease of LDH release. These data suggested that cytoplasm localization was necessary for the apoptosis induction by poly(I:C) and both MDA5 and RIG-I participated in that process (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Roles of different receptors in the intracellular poly(I:C)-induced melanocyte death. (A) Melanocytes were transfected with 1 μg/mL of poly(I:C) (TR) or treated with various concentrations of poly(I:C) (0, 1, 10, or 100 μg/mL) in the culture medium for 24 h. Protein levels of RIG-I, MDA5, and TLR3 were examined by western blotting. β-actin was probed as loading control. (B) Melanocytes were transfected with siRNAs targeting RIG-I, MDA5, TLR3, or a nonsilencing control, respectively. After 72 h, cells were harvested and the effects of siRNA were confirmed by western blotting. (C) Melanocytes were transfected with corresponding siRNAs. After 72 h, cells were mock transfected or transfected with 1 μg/mL poly(I:C). Cell death was evaluated by LDH release 24 h later. Results are presented as mean±SD from three experiments. *p<0.05 versus control siRNA.

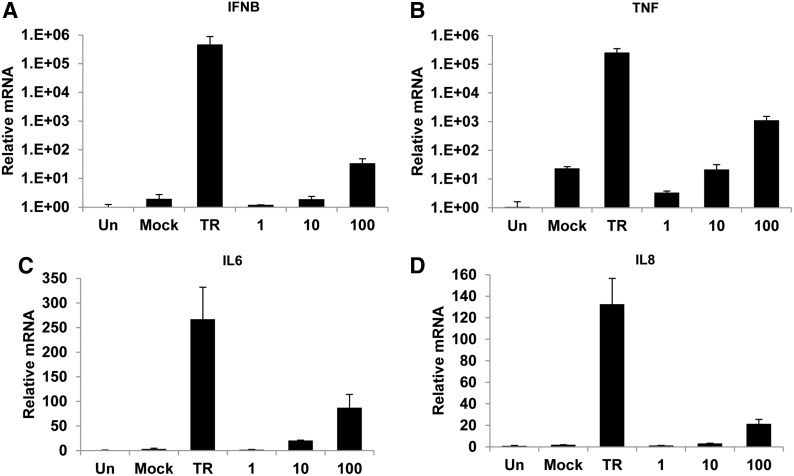

Differential induction of cytokine genes by intra- or extracellular poly(I:C)

To evaluate the effect of poly(I:C) on the production of cytokines, we measured the mRNA levels of IFNB, TNF, IL6, and IL8 in melanocytes after stimulation by poly(I:C) through quantitative real-time PCR. Intracellular poly(I:C) was shown to greatly upregulate the transcription of IFNB and TNF (a 4.7×105-fold and 2.5×105-fold increase compared with untreated cells, respectively). One hundred micrograms per milliliter of extracellular poly(I:C) also promoted the expression of IFNB and TNF, but to a lesser extent (68-fold and 1.1×103-fold, respectively) (Fig. 3A, B). In terms of IL6 and IL8, their expression was increased by both intracellular and 100 μg/mL of extracellular poly(I:C) with a smaller difference. Intracellular poly(I:C) increased the expression of IL6 and IL8 by about 267- and 132-fold, respectively. Whereas 100 μg/mL of extracellular poly(I:C) increased the expression of IL6 and IL8 about 87- and 21-fold, respectively (Fig. 3C, D).

FIG. 3.

Induction of cytokine genes by intra- or extracellular poly(I:C) in normal human melanocytes. Melanocytes were transfected with 1 μg/mL of poly(I:C) (TR) or treated with various concentrations of poly(I:C) (0, 1, 10, or 100 μg/mL) in the culture medium. Total RNA was extracted at 8 h after transfection. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed to measure the mRNA levels of IFNB (A), TNF (B), IL6 (C), and IL8 (D). Results are presented as mean±SD from three experiments.

Autocrine type I interferon or TNF-α is not required for poly(I:C)-induced melanocyte apoptosis

Among the cytokines that melanocytes produced, type I interferon and TNF-α have been reported to induce apoptosis in various cell types (Yanase et al., 1998; Akilov et al., 2012; Frias et al., 2012). We then evaluate the effects of secreted IFN-α, IFN-β, and TNF-α on poly(I:C)-induced melanocyte apoptosis using neutralization antibodies. The results demonstrated that blockade of neither cytokine showed a significant decrease to poly(I:C)-induced melanocyte apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. S2).

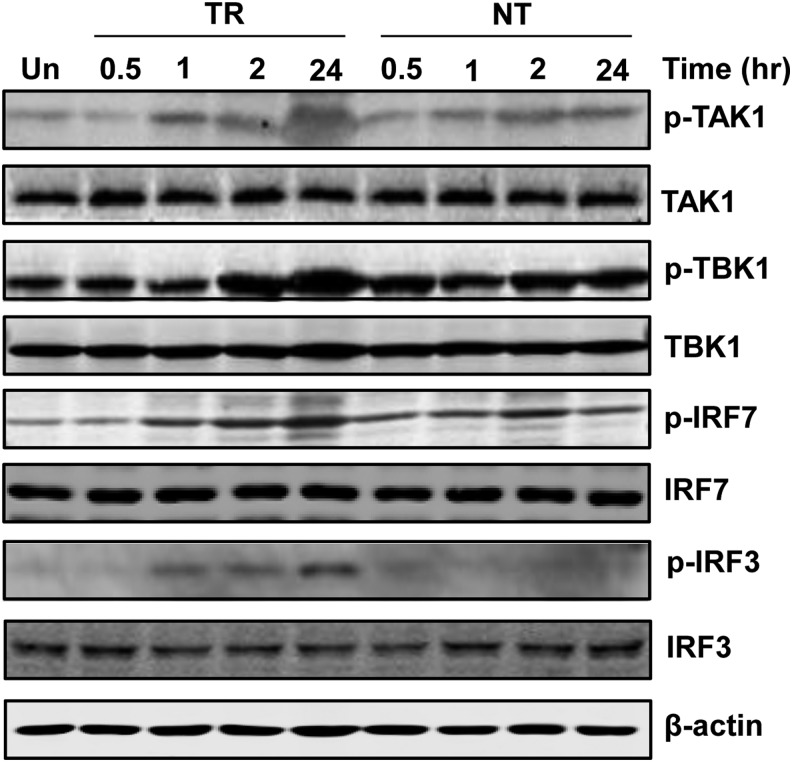

Phosphorylation of TAK1, TBK1, IRF3, and IRF7 in normal human melanocytes by poly(I:C) treatment

TAK1 and TBK1 have been reported to be involved in the expression of type I interferon and proinflammatory cytokines (Jiang et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2012). To characterize the activation of TAK1 or TBK1 pathways in melanocytes, we evaluated the cellular phosphorylation levels of TAK1, TBK1, as well as its downstream transcription factors IRF3 and IRF7 in normal human melanocytes at different times after treatment with intra- or extracellular poly(I:C). We determined that the phosphorylation of TAK1, TBK1, IRF3, and IRF7 was significantly upregulated by intracellular poly(I:C) in a time-dependent manner. Meanwhile, extracellular poly(I:C) weakly increased the phosphorylation of TAK1, TBK1, and IRF7. In terms of IRF3, its phosphorylation was not increased by extracellular poly(I:C) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylation profile of cytokine expression-related genes in normal human melanocytes in response to intra- or extracellular poly(I:C). Melanocytes were transfected with 1 μg/mL of poly(I:C) (TR) or treated with 100 μg/mL of poly(I:C) in the medium (NT) for 0.5, 1, 2, or 24 h. Cell lysates were processed for western blotting with antibodies against p-TAK1, TAK1, p-TBK1, TBK1, p-IRF3, IRF3, p-IRF7, and IRF7. β-actin was probed as loading control.

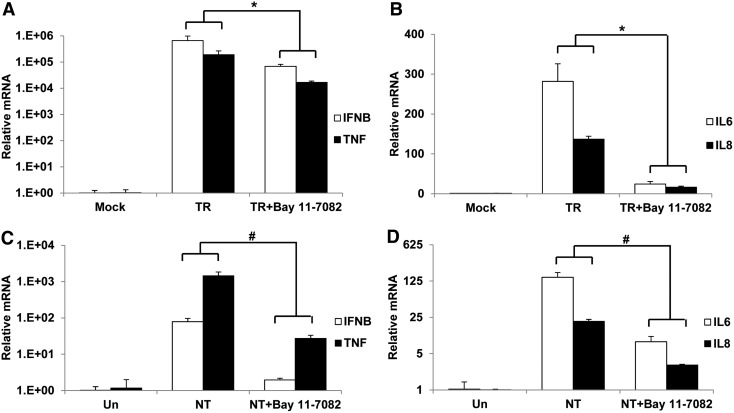

Ubiquitous involvement of NFκB activity in the cytokine induction by poly(I:C)

NFκB is an important transcription factor that regulates the expression of a wide range of genes. To elucidate whether NFκB has an effect on the induction of type I interferon and proinflammatory cytokines in normal human melanocytes by poly(I:C), we treated cells with Bay 11-7082, an inhibitor of NFκB activity. It was demonstrated that Bay 11-7082 significantly suppressed the gene induction of IFNB, TNF, IL6, and IL8 when melanocytes were stimulated with intra- or extracellular poly(I:C) (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Involvement of NFκB activity in the induction of cytokine genes by intra- or extracellular poly(I:C). Untreated or pretreated with 10 μM BAY 11-7082 for 1 h, melanocytes were then stimulated with 1 μg/mL of intracellular poly(I:C) (TR) or 100 μg/mL of extracellular poly(I:C) (NT). RNA was extracted after 8 h and quantitative real-time PCR was performed to measure the expression of IFNB and TNF (A, C) or IL6 and IL8 (B, D). Mock, Mock transfection. Un, Untreated control. Results are presented as mean±SD from three experiments. *p<0.05 versus TR, #p<0.05 versus NT.

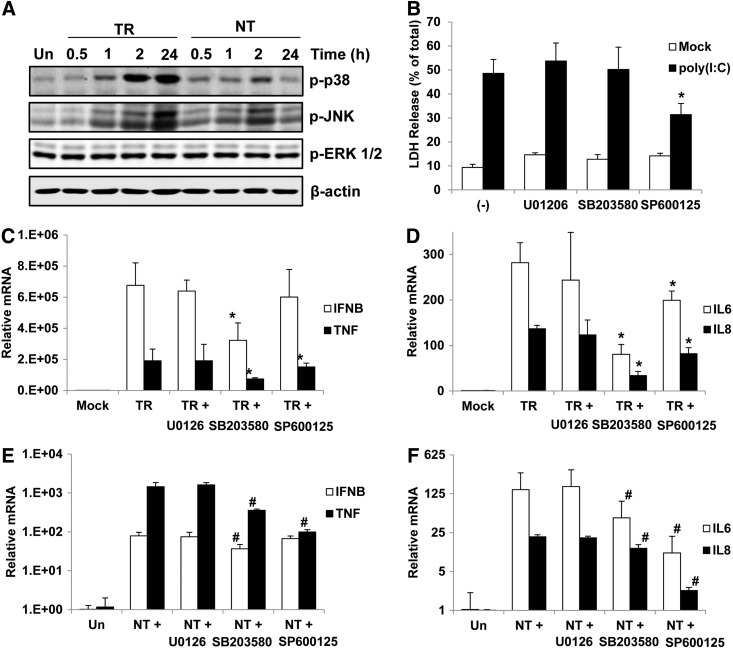

Activities of p38 and JNK in the melanocyte apoptosis and cytokine gene production after poly(I:C) treatment

MAPK activities especially p38 and JNK have also been reported to participate in the regulation of dsRNA-induced apoptosis and cytokine production (Yoshida et al., 2008; Mikkelsen et al., 2009). Significant phosphorylation of p38 and JNK was detected from 1 h after intracellular poly(I:C) stimulation. Comparatively, stimulation of p38 and JNK by extracellular poly(I:C) treatment was very weak and transient. Meantime, both intra- and extracellular poly(I:C) did not change the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 6A). To further address the roles MAPK activities in dsRNA-induced melanocyte apoptosis and cytokine production, we utilized pharmacological inhibitors to ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and JNK. As shown in Figure 6B, JNK kinase inhibition partially suppressed the LDH release after intracellular poly(I:C) stimulation. Whereas ERK1/2 and p38 inhibition did not affect the poly(I:C)-caused LDH release. Furthermore, blockade of p38 significantly decreased all of the intracellular poly(I:C)-induced cytokine expression. On the contrary, JNK inhibition decreased the expression of TNF, IL6, and IL8 to a lesser extent without changing the expression of IFNB (Fig. 6C, D). Comparatively, blockade of p38 activity showed limited effects on the extracellular poly(I:C)-induced cytokine expression, which was decreased more by JNK inhibition except expression of IFNB (Fig. 6E, 6F).

FIG. 6.

Effects of p38 MAPK and JNK activation on cell death and cytokine production in normal human melanocytes. (A) Melanocytes were treated with 1 μg/mL of intracellular poly(I:C) (TR) or 100 μg/mL of extracellular poly(I:C) (NT) for 0.5, 1, 2, or 24 h. Cell lysates were processed for western blotting with corresponding antibodies. (B) Untreated or pretreated with various MAPK inhibitors, melanocytes were mock transfected or transfected with 1 μg/mL of poly(I:C). After 24 h, LDH release was measured to evaluate cell death. (C–F) Melanocytes were pretreated with various MAPK inhibitors for 1 h and then stimulated with 1 μg/mL of intracellular poly(I:C) (TR) or 100 μg/mL of extracellular poly(I:C) (NT). RNA was extracted after 8 h and quantitative real-time PCR was performed to measure the expression of IFNB and TNF (C, E) or IL6 and IL8 (D, F). Results are presented as mean±SD from three experiments. *p<0.05 versus TR, #p<0.05 versus NT.

Discussion

Loss of epidermal melanocyte is the characteristic of vitiligo. The mechanism of vitiligo pathogenesis is complex. It has long been suspected that viral infection has a certain link with the onset and progress of vitiligo (Iverson, 2000). Our present results demonstrate that although only intracellular poly(I:C) induces significant apoptosis in normal human melanocytes, melanocytes respond to both intra- and extracellular dsRNA by expressing cytokines playing important roles in the regulation of adaptive immune responses (Laddha et al., 2012; Toosi et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014), including IFN-β, TNF-α, IL6, and IL8. It was reported that RNA released from necrotic keratinocytes, which might be the consequence of viral infection, activates TLR3 and upregulates the expression of ICAM-1 and numerous cytokines in melanocytes (Zhang et al., 2011). Therefore, viral infection can directly or indirectly trigger the innate immune responses in melanocytes, which contribute to a favorable milieu for the initiation of autoimmune reaction. The present study thus provides further support to the hypothesis about the viral factor in the pathogenesis of vitiligo.

RLR family members and TLR3 recognize intra- or extracellular dsRNA, respectively. Extracellular dsRNA induces apoptosis in some cell types through TLR3 (Sun et al., 2011; Estornes et al., 2012). Yu et al. reported TLR3-dependent apoptosis induction in human melanocytes by extracellular poly(I:C) (Yu et al., 2011). However, extracellular poly(I:C) treatment did not induce significant melanocyte death in our study. Instead, melanocyte apoptosis was only induced by intracellular poly(I:C), which is recognized by MDA5 and RIG-I. It is noticeable that the dsRNAs used in two studies were purchased from different providers. It is suggested previously that poly(I:C) with different lengths might display different effects (Avril et al., 2009; McNally et al., 2012). This may explain the discrepancy of outcomes from two studies. On the other hand, both extra- and intracellular poly(I:C) could induce the production of cytokines despite that less expression of all the tested genes was induced by extracellular poly(I:C) (Fig. 2). It was also reported that dsRNA-induced apoptotic cell death is mediated through the effect of IFN-β in an autocrine way (Dogusan et al., 2008; Fuertes Marraco et al., 2011). However, neither IFN-β blockade nor TNF-α blockade could rescue the melanocytes from poly(I:C)-induced cell death in our experiment (Supplementary Fig. S2), suggesting the involvement of other mechanism in the melanocyte death.

The TBK1 activity is necessary for the expression of type I interferons (Zhang et al., 2012). TBK1 regulates the transcription of IFNB through phosphorylating and activating IRF3 and IRF7 (Ikeda et al., 2007; Clark et al., 2011), while the expression of proinflammatory cytokines is critically controlled by TAK1 activity (Jiang et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2012). Furthermore, both TAK1 and IRF3 are suggested to participate in the process of apoptosis induction (Omori et al., 2006; Nakhaei et al., 2012). We demonstrated that intracellular poly(I:C) caused strong and persistent phosphorylation of IRF3 and IRF7, as well as TAK1 and TBK1. On the contrary, the stimulating effect on TAK1 and TBK1 activities by extracellular poly(I:C) is much weaker. Taken together, the differential phosphorylation profiles of TBK1, TAK1, IRF3, and IRF7 may account for the difference in apoptosis induction and cytokine gene expression in melanocytes following intra- or extracellular poly(I:C) treatment.

NFκB is an important transcription factor widely involved in the regulation of apoptosis, inflammation, immunity, and cell proliferation (Napetschnig and Wu, 2013). Both TBK1 and TAK1 activate NFκB and lead to downstream transcription. NFκB was reported to participate in the transcription regulation of type I interferon as well as proinflammatory cytokine genes (Wullaert et al., 2011). Consistent with previous findings, we showed that induction of cytokines by poly(I:C) was significantly suppressed by inhibition of NFκB activation indicating that NFκB is ubiquitously employed in the regulation of poly(I:C)-induced cytokine expression in normal human melanocytes. However, substantial remainder of cytokine expression could be observed, especially for the expression of IFNB and TNF in the presence of intracellular poly(I:C). It is assumed that NFκB works as an enhancer rather than an initiator in the regulation of cytokine expression.

Besides NFκB, a number of MAP kinases are involved in dsRNA-induced signaling. The duration and relative intensity of innate immune response depend on the synergy of NFκB with activities of MAP kinases (Lang et al., 2006). Poly(I:C)-caused expression of different cytokines is regulated preferentially by one or the other MAP kinase depending on cell types (Iordanov et al., 2000; Peters et al., 2002; Meusel and Imani, 2003). In this study, we showed that apoptosis and cytokine production in melanocytes induced by intra- or extracellular poly(I:C) were regulated by p38 MAPK and JNK at different degrees. Interestingly, although JNK inhibition decreased intracellular poly(I:C)-induced melanocyte apoptosis, it did not decrease the production of IFNB mRNA in the same condition. Comparatively, p38 inhibition significantly decreased the expression of IFNB in melanocytes in both conditions, especially upon intracellular poly(I:C) stimulation. We thus speculate that the p38 activity is a general participant in dsRNA-triggered cellular responses in melanocytes, whereas the role of JNK activity is restricted. However, more work needs to be performed to explain how JNK and p38 participate in the innate immune responses in melanocytes upon dsRNA stimulation.

In conclusion, this study presented the detailed effects of dsRNA on melanocyte viability and cytokine production in different conditions and elucidated part of the molecular signaling changes that mediate the cellular responses. However, further study is needed to gain further insight into the exact mechanism of viral infection-caused vitiligo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang (Grant No. LY13H110001), the Key Scientific Innovation Program of Hangzhou (20122513A02), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81271758 and 81472887). This research was also supported by the National Key Clinical Specialty Construction Project of China.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Akilov O.E., Wu M.X., Ustyugova I.V., Falo L.D., Jr, and Geskin L.J. (2012). Resistance of Sézary cells to TNF-α-induced apoptosis is mediated in part by a loss of TNFR1 and a high level of the IER3 expression. Exp Dermatol 21, 287–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avril T., de Tayrac M., Leberre C., and Quillien V. (2009). Not All polyriboinosinic-polyribocytidylic acids (Poly I:C) are equivalent for inducing maturation of dendritic cells: implication for α-type-1 polarized DCs. J Immunother 32, 353–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay S., and Sen G.C. (2014). dsRNA-activation of TLR3 and RLR signaling: gene induction-dependent and independent effects. J Interferon Cytokine Res 34, 427–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K., Takeuchi O., Akira S., and Cohen P. (2011). The TRAF-associated protein TANK facilitates cross-talk within the IkappaB kinase family during Toll-like receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 17093–17098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogusan Z., García M., Flamez D., Alexopoulou L., Goldman M., Gysemans C., et al. (2008). Double-stranded RNA induces pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis by activation of the Toll-like receptor 3 and interferon regulatory factor 3 pathways. Diabetes 57, 1236–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvic M., Rapini R., Hoots W.K., and Mansell P.W. (1987). Human immunodeficiency virus-associated vitiligo: expression of autoimmunity with immunodeficiency? J Am Acad Dermatol 17, 656–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estornes Y., Toscano F., Virard F., Jacquemin G., Pierrot A., Vanbervliet B., et al. (2012). dsRNA induces apoptosis through an atypical death complex associating TLR3 to caspase-8. Cell Death Differ 19, 1482–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias A.H., Jones R.M., Fifadara N.H., Vijay-Kumar M., and Gewirtz A.T. (2012). Rotavirus-induced IFN-β promotes anti-viral signaling and apoptosis that modulate viral replication in intestinal epithelial cells. Innate Immun 18, 294–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes Marraco S.A., Scott C.L., Bouillet P., Ives A., Masina S., Vremec D., et al. (2011). Type I interferon drives dendritic cell apoptosis via multiple BH3-only proteins following activation by PolyIC in vivo. PLoS One 6, e20189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes P.E., Sevall J.S., and Vojdani A. (1996). Cytomegalovirus DNA identified in skin biopsy specimens of patients with vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 35, 21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harson R., and Grose C. (1995). Egress of varicella-zoster virus from the melanoma cell: a tropism for the melanocyte. J Virol 69, 4994–5010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda F., Hecker C.M., Rozenknop A., Nordmeier R.D., Rogov V., Hofmann K., et al. (2007). Involvement of the ubiquitin-like domain of TBK1/IKK-i kinases in regulation of IFN-inducible genes. EMBO J 26, 3451–3462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iordanov M.S., Paranjape J.M., Zhou A., Wong J., Williams B.R., Meurs E.F., et al. (2000). Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase by double-stranded RNA and encephalomyocarditis virus: involvement of RNase L, protein kinase R, and alternative pathways. Mol Cell Biol 20, 617–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson M.V. (2000). Hypothesis: vitiligo virus. Pigment Cell Res 13, 281–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Mak T.W., Sen G., and Li X. (2004). Toll-like receptor 3-mediated activation of NF-kappaB and IRF3 diverges at Toll-IL-1 receptor domain-containing adapter inducing IFN-beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 3533–3538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Zamanian-Daryoush M., Nie H., Silva A.M., Williams B.R., and Li X. (2003). Poly(I-C)-induced Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3)-mediated activation of NFkappa B and MAP kinase is through an interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK)-independent pathway employing the signaling components TLR3-TRAF6-TAK1-TAB2-PKR. J Biol Chem 278, 16713–16719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalali B.N., Köllisch G., Mages J., Müller T., Bauer S., Wagner H., et al. (2008). Double-stranded RNA induces an antiviral defense status in epidermal keratinocytes through TLR3-, PKR-, and MDA5/RIG-I-mediated differential signaling. J Immunol 181, 2694–2704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H., Takeuchi O., Mikamo-Satoh E., Hirai R., Kawai T., Matsushita K., et al. (2008). Length-dependent recognition of double-stranded ribonucleic acids by retinoic acid-inducible gene-I and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5. J Exp Med 205, 1601–1610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T., Takahashi K., Sato S., Coban C., Kumar H., Kato H., et al. (2005). IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat Immunol 6, 981–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.Y., Jeong S., Jung E., Baik K.H., Chang M.H., Kim S.A., et al. (2012). AMP-activated protein kinase-α1 as an activating kinase of TGF-β-activated kinase 1 has a key role in inflammatory signals. Cell Death Dis 3, e357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laddha N.C., Dwivedi M., and Begum R. (2012). Increased tumor Necrosis factor (TNF)-α and its promoter polymorphisms correlate with disease progression and higher susceptibility towards vitiligo. PLoS One 7, e52298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R., Hammer M., and Mages J. (2006). DUSP meet immunology: dual specificity MAPK phosphatases in control of the inflammatory response. J Immunol 177, 7497–7504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.Y., and Fisher D.E. (2007). Melanocye biology and skin pigmentation. Nature 445, 843–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally B., Willette M., Ye F., Partida-Sanchez S., and Flaño E. (2012). Intranasal administration of dsRNA analog poly(I:C) induces interferon-α receptor-dependent accumulation of antigen experienced T cells in the airways. PLoS One 7, e51351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meusel T.R., and Imani F. (2003). Viral induction of inflammatory cytokines in human epithelial cells follows a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent but NF-kappa B-independent pathway. J Immunol 171, 3768–3774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen S.S., Jensen S.B., Chiliveru S., Melchjorsen J., Julkunen I., Gaestel M., et al. (2009). RIG-I-mediated activation of p38 MAPK is essential for viral induction of interferon and activation of dendritic cells: dependence on TRAF2 and TAK1. J Biol Chem 284, 10774–10782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakhaei P., Sun Q., Solis M., Mesplede T., Bonneil E., Paz S., et al. (2012). IκB kinase ɛ-dependent phosphorylation and degradation of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis sensitizes cells to virus-induced apoptosis. J Virol 86, 726–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napetschnig J., and Wu H. (2013). Molecular basis of NF-κB signaling. Annu Rev Biophys 42, 443–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori E., Matsumoto K., Sanjo H., Sato S., Akira S., Smart R.C., et al. (2006). TAK1 is a master regulator of epidermal homeostasis involving skin inflammation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem 281, 19610–19617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peisley A., Lin C., Wu B., Orme-Johnson M., Liu M., Walz T., et al. (2011). Cooperative assembly and dynamic disassembly of MDA5 filaments for viral dsRNA recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 21010–21015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters K.L., Smith H.L., Stark G.R., and Sen G.C. (2002). IRF-3-dependent, NFkappa B- and JNK-independent activation of the 561 and IFN-beta genes in response to double-stranded RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 6322–6327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar S., Chan H., Romanow W.J., Li J., and Bates R.J. (2006). IKK-i signals through IRF3 and NFkappaB to mediate the production of inflammatory cytokines. Cell Signal 18, 982–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R., Zhang Y., Lv Q., Liu B., Jin M., Zhang W., et al. (2011). Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) induces apoptosis via death receptors and mitochondria by up-regulating the transactivating p63 isoform alpha (TAP63alpha). J Biol Chem 286, 15918–15928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taieb A., and Picardo M. (2009). Clinical Practice. Vitiligo. N Engl J Med 360, 160–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toosi S., Orlow S.J., and Manga P. (2012). Vitiligo-inducing phenols activate the unfolded protein response in melanocytes resulting in upregulation of IL6 and IL8. J Invest Dermatol 132, 2601–2609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi H., Yonemoto K., and Katsuoka K. (2006). Vitiligo with inflammatory raised borders with hepatitis C virus infection. J Dermatol 33, 577–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Zhou M., Lin F., Liu D., Hong W., Lu L., et al. (2014). Interferon-γ induces senescence in normal human melanocytes. PLoS One 9, e93232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullaert A., Bonnet M.C., and Pasparakis M. (2011). NF-κB in the regulation of epithelial homeostasis and inflammation. Cell Res 21, 146–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanase N., Takada E., Yoshihama I., Ikegami H., and Mizuguchi J. (1998) Participation of Bax-alpha in IFN-alpha-mediated apoptosis in Daudi B lymphoma cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res 18, 855–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida R., Takaesu G., Yoshida H., Okamoto F., Yoshioka T., Choi Y., et al. (2008). TRAF6 and MEKK1 play a pivotal role in the RIG-I-like helicase antiviral pathway. J Biol Chem 283, 36211–36220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N., Zhang S., Sun T., Kang K., Guan M., and Xiang L. (2011). Double-stranded RNA induces melanocyte death via activation of Toll-like receptor 3. Exp Dermatol 20, 134–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Wang L., Zhao X., Zhao K., Meng H., Zhao W., et al. (2012). TRAF-interacting protein (TRIP) negatively regulates IFN-β production and antiviral response by promoting proteasomal degradation of TANK-binding kinase 1. J Exp Med 209, 1703–1711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Liu S., Yu N., and Xiang L. (2011). RNA released from necrotic keratinocytes upregulates intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in melanocytes. Arch Dermatol Res 303, 771–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.