Summary

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes such as INO80 have been implicated in checkpoint regulation in response to DNA damage. However, how chromatin remodeling complexes regulate DNA damage checkpoints remain unclear. Here, we identified a mechanism of regulating checkpoint effector kinase Rad53 through a direct interaction with the INO80 chromatin remodeling complex. Rad53 is a key checkpoint kinase downstream of Mec1. Mec1/Tel1 phosphorylates the Ies4 subunit of the INO80 complex in response to DNA damage. We find that the phosphorylated Ies4 binds to the N-terminal FHA domain of Rad53. In vitro, INO80 can activate Rad53 kinase activity in an Ies4-phosphorylation dependent manner in the absence of known activators such as Rad9. In vivo, Ies4 and Rad9 function synergistically to activate Rad53. These findings establish a direct connection between ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes and checkpoint regulation.

Keywords: Chromatin remodeling, checkpoint regulation, INO80, Rad53, FHA domain

Introduction

Eukaryotic cells have evolved a complex system to deal with DNA damage, which include checkpoint activation, DNA repair and other processes to safeguard genome integrity. In yeast, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-related protein kinases (PIKK) Mec1 and Tel1 (ATR and ATM in mammals) are the master regulators of DNA damage response (DDR) (Gobbini et al., 2013). Mec1/Tel1 promotes the activation of downstream effector kinases such as S. cerevisiae Chk1 and Rad53 (CHK1 and CHK2 in mammals), which function to target downstream components of the DDR as well as amplifying the initial DDR signal (Stracker et al., 2009).

In S. cerevisiae, Mec1 activates both Rad53 and Chk1, while in mammalian cells ATM primarily activates Chk2 (Rad53 in budding yeast) and ATR activates Chk1 (Sanchez et al., 1999; Stracker et al., 2009). Downstream of Mec1/Tel1, activation of the effector kinases is regulated by mediator proteins, such as S. cerevisiae Rad9 (equivalent to 53BP1, BRCA1, MDC1 in mammals) that function as molecular adaptors to recruit and activate the Rad53 effector kinase (Harper and Elledge, 2007).

One of the earliest events at a DSB is the phosphorylation of S129 of H2A by Mec1/Tel1 (Rogakou et al., 1999; Rogakou et al., 1998). Recruitment of ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes to DSBs and the remodeling of the surrounding chromatin occurs on a similar timescale to H2A phosphorylation. It has been shown that the phosphorylation of the Ies4 subunit of the INO80 chromatin remodeling complex by Mec1/Tel1 in response to DNA damage directs INO80 function towards checkpoint regulation (Morrison et al., 2007; Morrison and Shen, 2009). However, how a chromatin remodeling complex such as INO80 complex participates in checkpoint regulation remain unanswered.

In this study, employing biochemical approaches, we reveal that the INO80 complex directly binds and helps activate the effector kinase Rad53 to regulate DNA damage checkpoint response. We find that the binding and activation of Rad53 by the INO80 complex requires the Ies4 subunit of INO80 in a phosphorylation dependent manner. The underlying molecular mechanism is an interaction between phosphorylated Ies4 and the N-terminal fork-head associated (FHA) domain of Rad53. These findings reveal a direct mechanism of checkpoint kinase activation through interaction with an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex.

Results

Interaction of Rad53 N-terminal FHA domain with the phospho-Ies4 subunit of the INO80 complex

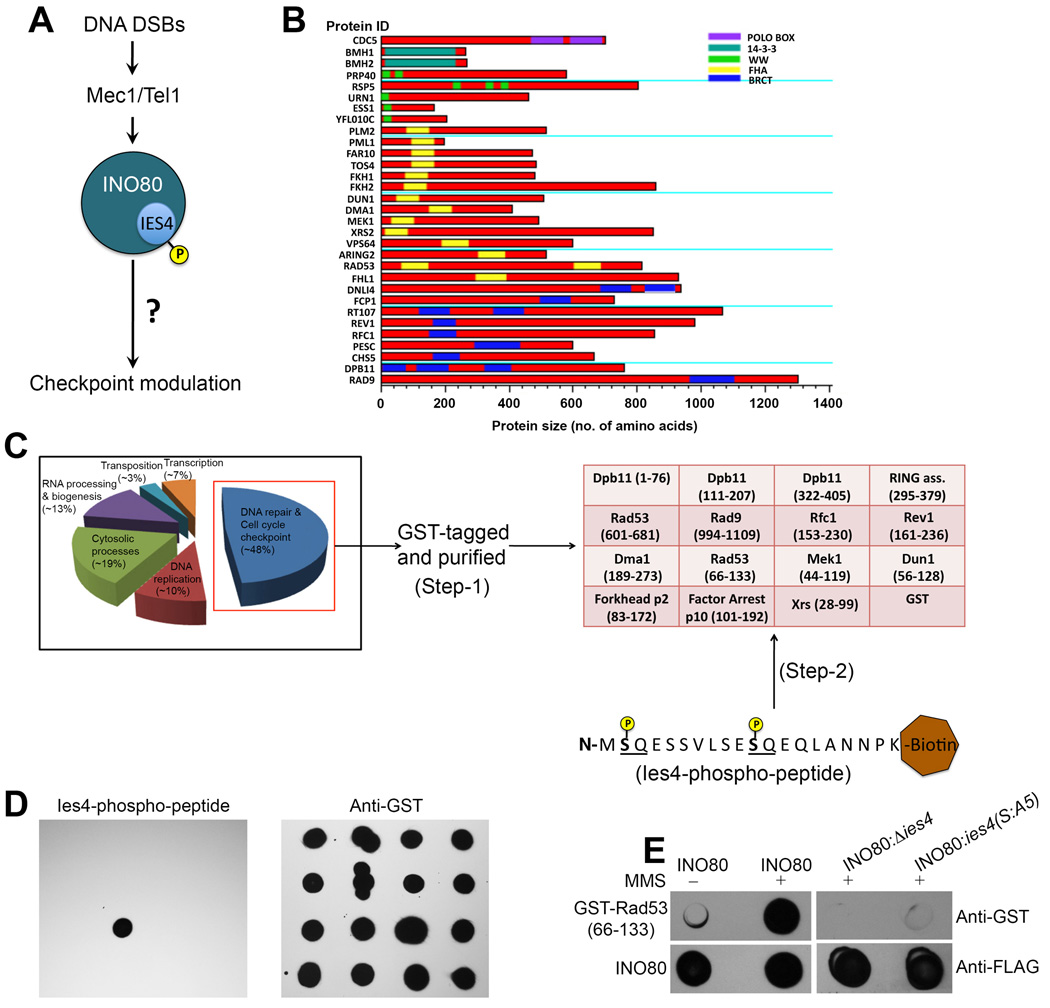

The INO80 chromatin remodeling complex belongs to a highly conserved subfamily of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex superfamily (Bao and Shen, 2007b). INO80 has been implicated in both DNA repair and checkpoint regulation (Morrison and Shen, 2009). In checkpoint regulation, Mec1/Tel1-mediated phosphorylation of the INO80 subunit Ies4 is functionally implicated in the DNA damage checkpoint (Morrison et al., 2007; Morrison and Shen, 2009), however, the mechanism by which the INO80 complex regulates the checkpoint response remains elusive (Figure 1A). Given the roles of INO80 in transcription and DNA repair, we initially thought that INO80 might regulate checkpoint indirectly, either through affecting the transcription of checkpoint regulators or through changes in chromatin at DNA damage sites. To begin addressing the mechanisms that link chromatin remodeling complex to checkpoint regulation, we reasoned that there might be factors that can read the Ies4 phosphorylation signal on INO80 to regulate the checkpoint response. In this context, we screened the yeast proteome for proteins comprising phospho-Ser/Thr recognition domains on the basis of their primary sequence analysis (Reinhardt and Yaffe, 2013), and observed 32 proteins containing 39 potential phospho-Ser/Thr recognition domains (Figure 1B and Table S1). Furthermore, functional assignment of these known factors categorizes 48% of the proteins to be involved in DNA damage response and cell cycle checkpoint control (Figure 1C and Table S1). In a proteomic approach to identify the binders of Ies4 phosphorylation in the INO80 complex in response to DNA damage, we purified the phospho-binding domains from proteins in this DNA repair/checkpoint category with an N-terminal GST tag, and generated a protein domain array on a nitrocellulose membrane (Figures 1C, step 1 and S1). This protein domain array was then used for screening of potential binders of Ies4 phospho-peptides.

Figure 1. Interaction of Rad53-N-FHA with the phospho-Ies4 subunit of the INO80 complex.

(A) Schematic diagram for the pathway showing Mec1/Tel1-dependent modulation of cell cycle checkpoint control via the INO80 complex. (B) Proteome-wide analysis of S. cerevisiae for phospho-S/T binders, represented by the horizontal bar graph, showing the length of identified proteins and their respective phospho-S/T recognition domains in it on the X-axis, and protein identity (ID) on the Y-axis. See also Table S1. (C) Graph showing functional identification and categorization of the proteins identified in (B), which shows a major fraction (~40%) of factors involved in DNA damage repair and cell cycle checkpoint control. These purified factors with an N-terminal GST tag were further used to generate the protein domain array for the identification of phospho-Ies4 peptide binders as represented by the two-step schematic diagram. See also Figure S1. (D) Dot blot showing identification of Rad53-N-FHA as a reader of phospho-Ies4 peptide with the known phosphorylation sites. The phospho-Ies4 peptide was covalently coupled with biotin and the interaction was detected by strepavidin-HRP (left panel), whereas the presence of all the domains on the array was confirmed using anti-GST antibodies. (E) Dot blot showing the interaction of the INO80 complex with GST-tagged Rad53-N-FHA. The INO80 complexes were purified after DNase treatment during purification followed by high salt washes that removes the traces of the bound chromatin, in presence/absence of MMS as indicated at the top of the blot, and the complexes were then immobilized onto the nitrocellulose membrane. The interaction of GST-tagged Rad53-N-FHA with the INO80 complex was detected using anti-GST antibodies (upper panel), whereas, the presence of INO80 onto the nitrocellulose membrane was confirmed by anti-FLAG antibodies (lower panel).

Given that Ies4 phosphorylation occurs at SQ motifs present at its N-terminal end (Morrison et al., 2007), we chemically synthesized both phosphorylated- and unphosphorylated-Ies4 N-terminal peptides with the covalently linked biotin at the C-termini. We screened the phospho-binding protein domain array with a biotin-streptavidin detection system (Figure 1C, step 2). While the unphosphorylated peptide did not show interaction signal with any protein domain on the array (data not shown), the phosphorylated peptide showed a specific interaction with the N-terminal FHA domain of Rad53 (Rad53-N-FHA) (Figure 1D). Interestingly, Rad53 contains two FHA domains. The C-terminal FHA domain of Rad53 (Rad53-C-FHA) present on the same array did not showed any interaction with the phospho-Ies4 peptide (Figure 1D). These results indicate that Rad53 could be a potential interacting partner for the phospho-Ies4 subunit of the INO80 complex, specifically through the Rad53-N-FHA domain.

To further confirm this interaction, we immobilized INO80 complex purified in the absence/presence of the DNA damaging agent MMS, onto the nitrocellulose membrane. We then probed the immobilized complex with the purified GST-tagged Rad53-N-FHA domain and detected the interaction with anti-GST antibodies. INO80 purified in the absence of MMS (which still contains a low basal level of Ies4 phosphorylation (Morrison et al., 2007) showed weak interaction with Rad53-N-FHA. However, INO80 purified after MMS treatment (containing high levels of Ies4 phosphorylation (Morrison et al., 2007)) showed stronger interaction with Rad53-N-FHA (Figure 1E). Furthermore, the INO80 complex purified from an Δies4 mutant, as well as from a phospho-blocking ies4 (S:A5) mutant in the presence of MMS, did not showed any significant interaction with Rad53-N-FHA (Figure 1E). Given that the Ies4 subunit of the INO80 complex is phosphorylated at specific SQ sites by Mec1/Tel1 in the presence of MMS, these results suggest that phosphorylation of the Ies4 subunit in INO80 is mainly responsible for the specific interaction with Rad53-N-FHA, providing an unexpected direct mechanism to connect a chromatin remodeling complex to a key checkpoint kinase. Moreover, this protein interaction study also established a biochemical screening system to identify the interacting partners for other phospho-peptides involved in DNA damage response pathways.

INO80 interacts with Rad53 and enhances Rad53 activation in vivo

To test the physiological relevance of the interaction of the phospho-Ies4 subunit of the INO80 complex with Rad53-N-FHA domain in response to DNA damage, we carried out an INO80 pull-down experiment in the absence/presence of MMS, followed by probing the pull-down complex with anti-Rad53 antibodies. Although the detectable basal level of interaction of Rad53 was observed with INO80 in the absence of MMS (likely due to the basal level of Ies4 phosphorylation (Morrison et al., 2007)), Rad53 showed an increase in interactions with INO80 in the presence of MMS (Figure 2A). This result suggests that Rad53 physically interacts with INO80 after DNA damage. Interestingly, given that activated Rad53, upon phosphorylation, has slower mobility than unphosphorylated Rad53 in SDS PAGE (Alcasabas et al., 2001), our results also suggest that most of Rad53 interacting with the INO80 complex in the presence of DNA damage is in its active form, as detected by the upward smearing of Rad53 on the blot (Figure 2A, lane 2). In contrast, consistent with the previous results, INO80 pull-down from an Δies4 mutant, or phospho-blocking ies4 (S:A5) mutant showed a reduction in the interaction between Rad53 and INO80 in the presence of MMS, and the residual Rad53 was not in the activated form (Figure 2A). These results further confirms that the phosphorylation of the Ies4 subunit makes a major contribution to Rad53 interaction with the INO80 complex upon DNA damage, although contributions from other subunits or other posttranslational modifications cannot be ruled out. These results also suggest that the interaction between INO80 and Rad53 may lead to the enhancement of Rad53 activation.

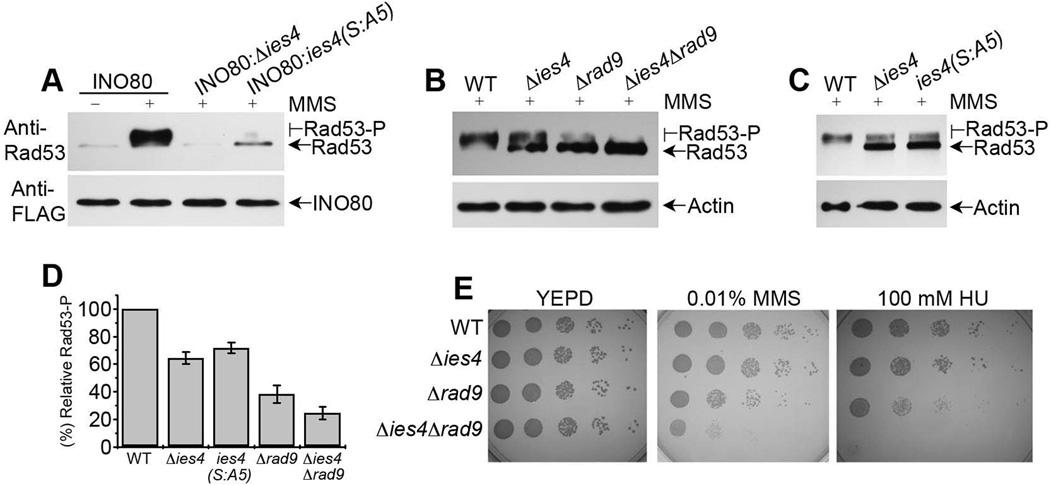

Figure 2. In vivo enhancement of Rad53 activation by the Ies4 subunit of the INO80 complex.

(A) Western blot analysis of the purified INO80 complex in the presence/absence of MMS from wild type and ies4 mutant cells as indicated at the top, and probed using anti-Rad53 antibodies. Rad53 shows a substantial interaction with the INO80 complex purified in the presence of MMS with a major phophorylated population as detected by retarded band. (B, C) Western blot analysis of wild type and mutant cells in presence of MMS for ~ 30 min. as indicated at the top of the blot, using anti-Rad53 antibodies. (D) Graph showing relative Rad53 activation in mutant cells in (B, C), with wildtype cells as 100%. Data are represented as mean of three independent experiments +/− SEM. (E) Genetic interaction analysis, showing Ies4 and Rad9 as the parallel pathways in response to DNA damage. Wild type and mutant cells as indicated at the left of the panel were grown on YEPD, 0.01% MMS, and 100 mM HU plates with serial dilutions for three days. See also Figure S2.

To investigate the relationships between INO80 and the established Rad53 activation mechanisms, we examined the genetic interactions between Ies4 and Rad9, a known activator of Rad53 (Pellicioli and Foiani, 2005; Pellicioli et al., 1999; Schwartz et al., 2002; Toh and Lowndes, 2003). Upon 30-minute MMS treatment, deletion of Ies4 leads to ~40% reduction of Rad53 activation, while the deletion of Rad9 leads to ~70% reduction (Figures 2B–D). In an early study (Morrison et al., 2007), after 2-hour MMS treatment, Rad53 activation is normal in ies4 mutant, suggesting Ies4 contributes to early kinetics of Rad53 activation. When we deleted ies4 in a Δrad9 background, the activation of Rad53 was further decreased to ~10% in the Δies4 Δrad9 double deletion mutant when compared to Δies4 or Δrad9 single deletion mutants (Figures 2B-D). Given that Rad9 activates Rad53 in response to DNA damage (Schwartz et al., 2002), further decrease in the Rad53 activation upon ies4 deletion in Δrad9 background suggests that the INO80 complex may make an additional contribution to Rad53 activation independent of Rad9.

Moreover, the growth of Δies4 Δrad9 double deletion mutants showed more severe growth defects in the presence of 0.01% MMS and in the presence of 100 mM HU, compared to WT, Δies4 or Δrad9 single deletion mutants (Figure 2E). The growth defect was partially rescued after expressing wildtype Ies4 in the Δies4 Δrad9 double deletion background under similar conditions (Figure S2). Moreover, the ies4 (S:A5) mutant showed similar Rad53 activation defect as Δies4 (Figure 2C), indicating that the Ies4 phosphorylation by Mec1/Tel1 is required for Rad53 activation in vivo as well. Together, these synthetic genetic analyses are consistent with the notion that Ies4/INO80 may be part of a Rad53 activation mechanism distinct from the Rad9-mediated Rad53 activation mechanism (Schwartz et al., 2002), and that the both mechanisms are downstream of Mec1/Tel kinases. These results are also consistent with the genome-wide genetic interaction analyses of ies4 mutants in which IES4 was found to genetically interact with several checkpoint factors (Morrison et al., 2007). Since the phosphorylation of Rad53 is regulated in response to DNA damage by multiple factors (Heideker et al., 2007), these results are consistent with an additional mechanism for the synergistic amplification of Rad53 phosphorylation upon DNA damage.

INO80 activates Rad53 kinase activity in vitro in an Ies4- and phosphorylation-dependent anner

Given that INO80 physically interacts with Rad53, and that the INO80-associated Rad53 was in an activated state, we investigated whether the purified INO80 complex could activate Rad53 in vitro. Since potential contamination of Rad9 may also activate Rad53 in the purified INO80 complex, we purified the INO80 complex from a Δrad9 mutant in the presence/absence of MMS. Using the INO80 complex purified from Δrad9 mutants, we then carried out the in vitro Rad53 assays (Rad53 was immunopurified using a strain with HA tag at the C-terminus of RAD53 in the genome, Figure 3A). Compared to the controls, we observed an increase in the activation of Rad53 by the INO80 complex purified in the presence of MMS as indicated by the upward smear of phosphorylated Rad53 (Figures 3B-D and S3B). The weaker Rad53 activation by INO80 purified from cells without MMS treatment is likely due to the basal level of Ies4 phosphorylation (Morrison et al., 2007).

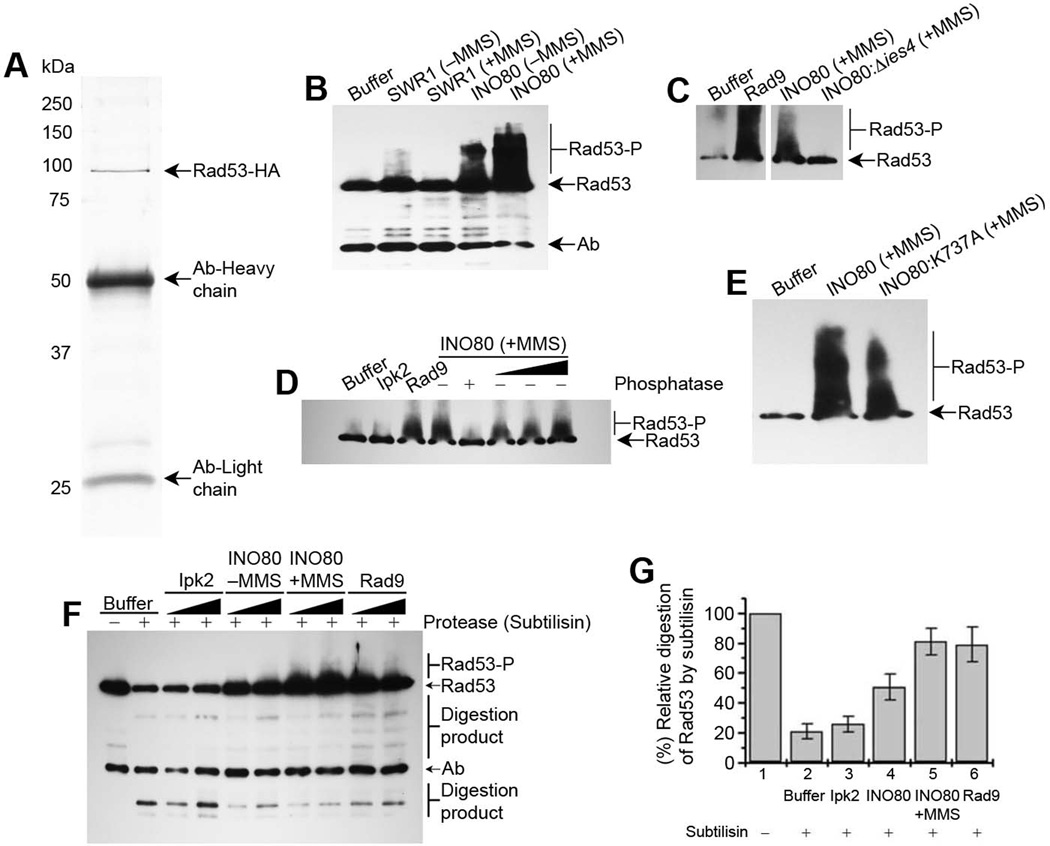

Figure 3. In vitro enhancement of Rad53 activation by the Ies4 subunit of the INO80 complex.

See also Figure S3. (A) SDS PAGE after silver staining showing purification of Rad53-HA from S. cerevisiae after inserting a HA tag at the C-terminus of RAD53 in the genome and purified using anti-HA beads. (B-D) Western blot analysis of purified Rad53-HA, using anti-HA antibodies, showing in vitro activation of Rad53 in the presence of; (B) INO80 compare to SWR1 complex (10 nM each) purified in the presence/absence of MMS; (C) Wild type and ies4 mutant INO80 complexes (10 nM) compared to Rad9 (10 nM) in the presence of MMS; (D) INO80 complex (10 nM) purified in presence/absence of alkaline phosphatase compared to an unrelated kinase Ipk2 (10 nM) as a negative control, and Rad9 (10 nM) as a positive control. (E) Western blot analysis of purified Rad53-HA, using anti-HA antibodies, showing in vitro activation of Rad53 in the presence of Wild type INO80 complex (10 nM) compared to its ATPase dead mutant INO80 (K737A) (10 nM), as indicated at the top of the blots. (F) Protease mapping of Rad53-HA, shown by the western blot analysis of purified Rad53-HA preincubated separately with the different purified components, and further treated with the protease subtilisin (1:1000, subtilisin:Rad53-HA), as indicated at the top of the blot. The simultaneous activation of Rad53 was also observed in the same reaction with INO80 or Rad9, which was due to the pre-incubation of Rad53-HA with INO80 or Rad9 respectively. INO80, Rad9, and Ipk2 were used in equimolar concentrations. (G) Graph showing percentage relative digestion of Rad53 by subtilisin (undigested band of Rad53 /digested band below the light chain antibodies band) as shown in Figure 3F. Data are represented as mean of three independent experiments +/− SEM.

Given that the SWR1 complex also belongs to the INO80 family, we examined whether the SWR1 complex might also activate Rad53 in vitro. In contrast to the INO80 complex, SWR1 was incapable of activating Rad53 in vitro (Figure 3B). These results suggest that Rad53 activation is specifically associated with the INO80 complex in the INO80 family. Furthermore, Rad53 activation by INO80 was comparable to the in vitro activation of Rad53 by purified Rad9 (Rad9 was immuno-purified using a strain with HA tag at the C-terminus of RAD9 in the genome) (Figures 3C and S3C), which is a known activator of Rad53 (Gilbert et al., 2001). Interestingly, INO80 purified from the Δies4 strain in the presence of MMS did not make a substantial contribution to the activation of Rad53 (Figure 3C), suggesting that the Ies4 subunit is required for Rad53 activation by the INO80 complex. Moreover, Rad53 was also not activated by the purified INO80 complex in the presence of MMS, which was pre-treated with alkaline phosphatase on beads during purification followed by extensive high salt washing (Figure 3D). Phosphatase-treated INO80 regains the activity to Rad53 activation after addition of freshly purified INO80 complex after MMS treatment without alkaline phosphatase treatment in the same reaction (Figure 3D). The phosphatase treatment result also confirms that Rad53 activation by INO80 is phosphorylation-dependent. Taken together, these results suggest that upon DNA damage, Mec1/Tel1 phosphorylate INO80 subunits such as Ies4, and the phosphorylated Ies4 then binds to the N-terminal FHA domain of Rad53 and enhances Rad53 activation. Together, the in vitro assays suggest an unexpectedly direct mechanism of Rad53 activation distinct from the Rad9-mediated Rad53 activation (Pellicioli and Foiani, 2005; Pellicioli et al., 1999; Schwartz et al., 2002; Toh and Lowndes, 2003).

As a member of the ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes, INO80 remodels chromatin by interacting with chromatin substrates. Chromatin interactions trigger INO80 ATPase activity, which leads to the disruption of DNA and histone contacts in nucleosomes. The Ino80 core ATPase is the main ATPase in the INO80 complex and the ATPase-dead mutant of Ino80 (K737A) abrogates most of the ATPase activity and remodeling activities of the INO80 complex (Mizuguchi et al., 2004; Shen et al., 2000; Shen et al., 2003). We investigated whether the INO80 ATPase activity is involved in Rad53 activation in response to DNA damage. We purified the INO80 complex from the K737A mutant in the presence of MMS, and examined the Rad53 activation in vitro. Although the activation of Rad53 by mutant INO80 (K737A) was affected compared to the WT INO80 in presence of MMS, it did not result in the complete loss of activation (Figures 3E and S3D). These results suggest that in contrast to the absolute requirement of INO80 ATPase activity in chromatin remodeling, the ATPase activity of the INO80 complex is partially required for Rad53 activation and may facilitate the optimal activation of Rad53. It is possible that the level of Ies4 phosphorylation in the INO80 (K737A) mutant may be reduced, which results in the reduction in Rad53 activation. Our results are consistent with a model in which the phospho-Ies4 subunit of INO80 might function as a scaffold for non-chromatin proteins such as Rad53, which helps Rad53 leading to its activation. A similar role has been proposed for Rad9 (Gilbert et al., 2001).

INO80 interacts and protects Rad53 from proteolysis

If INO80 interacts directly with Rad53, it could protect Rad53 from proteolysis. To address this, we performed protease mapping of purified Rad53 upon interaction with the purified INO80 complex using subtilisin as a protease probe. Compared to controls, Rad53 was more protected by the INO80 complex from subtilisin digestion, and this protection was comparable to that of the interaction between Rad53 and Rad9. In contrast, an unrelated kinase Ipk2 did not protect the subtilisin digestion of Rad53 under similar conditions (Figures 3F and 3G). It should be noted that in the limited subtilisin digestion assay, the purified Rad53 pre-incubated with Rad9 or the INO80 complex also showed simultaneous Rad53 activation in the same subtilisin digestion reaction (Figure 3F, lane 7–10), suggesting that the interaction between INO80 and Rad53 not only leads to protection of Rad53 from protease digestion, but also leads to Rad53 activation. As such, the binding of Rad53 by INO80 may enhance the stability of Rad53 in vitro. These results are consistent with direct interactions of Rad53 with the INO80 complex, leading to the stimulation of Rad53 kinase activity. Taken together, our study provides a direct molecular mechanism underlying checkpoint regulation by ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes (Figure 4).

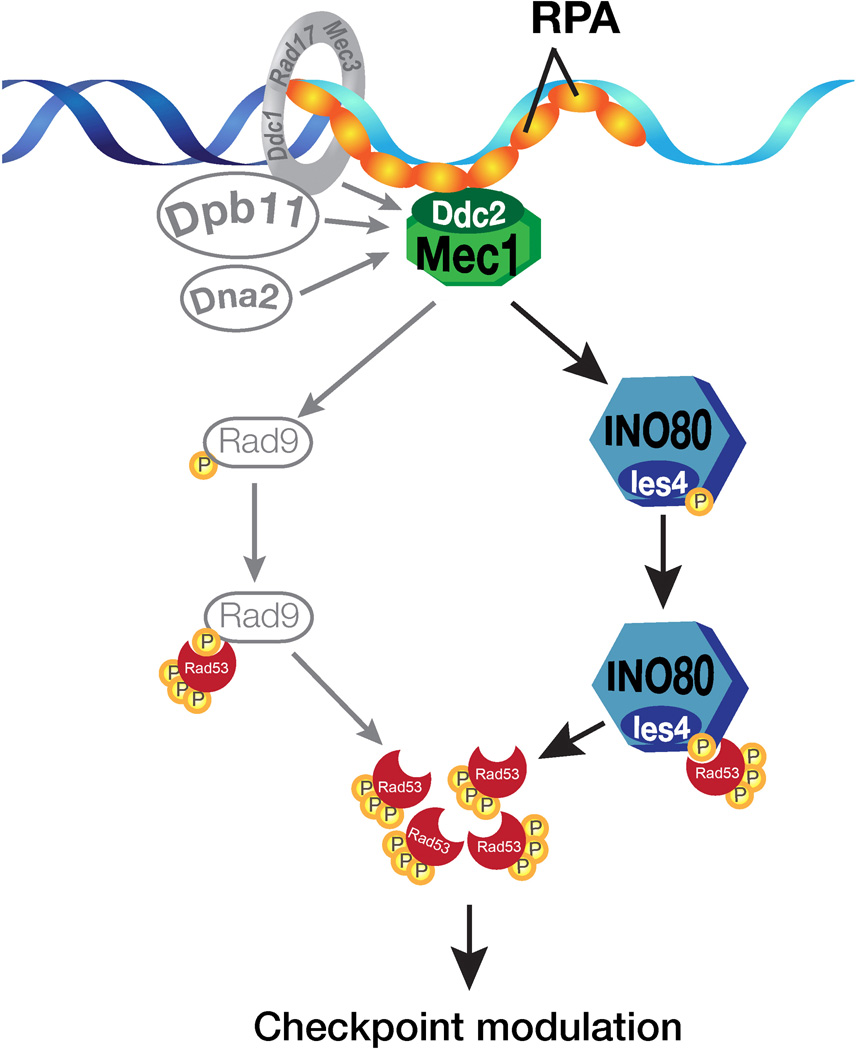

Figure 4. Model showing the mechanism of regulation of checkpoint kinase Rad53 by INO80 chromatin remodeling complex.

Discussion

A direct link between chromatin remodeling complex and checkpoint kinase

The role of chromatin remodeling in transcription is well established, and recent studies revealed links between chromatin remodeling complexes and other nuclear events such as DNA repair and checkpoint regulation (Bao and Shen, 2007a; Morrison and Shen, 2009; van Attikum and Gasser, 2009). The INO80 complex is also involved in the regulation of the DNA damage checkpoint (Morrison et al., 2007). Despite these emerging links, the underlying mechanism how chromatin remodeling complexes such as the INO80 complex regulate the checkpoint remain unknown.

Given that the chromatin remodeling complexes regulate transcription, it is plausible that the checkpoint regulation by chromatin remodeling complexes is indirect. However, through a proteomic study, we provide evidence for a surprisingly direct role of the INO80 chromatin remodeling complex in the regulation of the key checkpoint kinase Rad53. Combining biochemical and genetic approaches, we have shown that INO80 offers a mechanism of Rad53 regulation in response to DNA damage. Together, our results suggest additional mechanisms outside of Rad9 to help relay the Mec1 checkpoint activation signal to Rad53. INO80 acts downstream of Mec1, binds and activates effector kinase Rad53 through its Ies4 subunit in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (Figure 4). In addition to the classical checkpoint regulation mechanism, our studies reveal a direct mechanism of Rad53 regulation through ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex. It is likely that additional interactions between ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes and checkpoint factors will be discovered in future studies.

Phosphorylation-dependent enhancement of Rad53 activity by INO80 chromatin remodeling complex

It has been shown that the downstream effector kinases such as Rad53 are synergistically phosphorylated in response to DNA damage to amplify the DDR signal (Stracker et al., 2009). Given that Rad9 is a known activator of Rad53, the INO80 complex could potentially function in the same pathway; however our genetic interaction analysis suggests that Ies4-mediated Rad53 activation is distinct from the Rad9-mediated Rad53 activation (Figure 2E). Furthermore, we showed that in vitro, INO80-mediated Rad53 activation was comparable to Rad9-mediated Rad53 activation (Figures 3C and 3D). These results not only suggest a pathway of Rad53 activation, but also explain the synergistic amplification of Rad53 phosphorylation in response to DNA damage. As such, our study suggests a mechanism to activate Rad53, which can either further amplify Rad9-based Rad53 activation, or serve as a backup mechanism to the Rad9 pathway. The multiple mechanisms to activate Rad53 ensure robustness and redundancy in checkpoint regulation.

How might INO80 activate Rad53? We have shown that the phosphorylated Ies4 subunit of the INO80 complex interacts with the N-terminal FHA domain of Rad53 (Figures 1D and 1E); however Ies4 and its phospho-mimic mutant proteins alone are unable to activate Rad53 (Figure S3E). Given that Rad53 has two FHA domains, it is likely that Rad53, apart from interacting Ies4, also interacts with other sites on the INO80 complex, perhaps through its C-terminal FHA domain. As such, the activation of Rad53 by INO80 requires not only Ies4 phosphorylation, but also the intact INO80 complex (Figures 3C and 3D). Although INO80 activates Rad53 separately from Rad9, the underlying Rad53 activation mechanisms might be similar to those of Rad9. Our in vitro experiments suggest that Rad53 activation by INO80 is not completely ATP-dependent, suggesting that Ies4/INO80 can activate Rad53 similar to Rad9 by forming a scaffold. On the other hand, the ATPase-dead INO80 complex has a reduced ability to activate Rad53. The partial ATP-dependence of Rad53 activation by INO80 suggests that either the ATPase-dead INO80 complex has reduced level of Ies4 phosphorylation, or that ATP-dependent conformational changes in INO80 can further facilitate Rad53 binding or activation. Further studies will be needed to dissect the activation mechanisms.

A platform to study phosphorylation-dependent protein interactions

Our biochemical screening of the yeast proteome for factors comprising phospho-Ser/Thr recognition domains identified that the Rad53-N-FHA domain specifically interacts with the phosphopeptide of Ies4 (Figure 1). The screening of phospho-Ser/Thr recognition domains using this phospho-protein binding domain array provides a platform for the screening of other phospho-peptides interactions with the known factors involved in checkpoint signaling. It is worth noting that the FHA domain of Rad53 is known to bind phosphothreonine in Rad9 (Li et al., 2000). Our findings suggest that FHA domain can also bind to phosphoserine such as the pSQ motif found in Ies4, consistent with reports of other FHA domains binding to phosphoserines (Li et al., 2000). Thus, the phospho-binding protein array provides a tool for understanding the complex phosphorylation-dependent protein interactions during DNA damage response.

Chromatin remodeling complexes interacts with non-chromatin proteins

Although the interactions between INO80 and non-chromatin proteins such as tubulin have been reported previously, the biological significance of such interactions by ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes remains unclear (Park et al., 2011). Our studies of INO80-mediated Rad53 activation reveals a mechanism of checkpoint regulation through the direct interaction of non-chromatin proteins such as Rad53 with ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes such as INO80 (Figure 4). These examples highlight that ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes, like the histone modifying enzymes (Sapountzi and Cote, 2011; Shi et al., 2007), can also interact and regulate non-chromatin proteins.

Experimental Procedures

Strains and Plasmids

Standard yeast genetic techniques were used to create gene deletions and epitope12-tagged strains (Supplemental Table S2). Construction of the BY4741 strain encoding RAD53 and RAD9 with a chromosomal triple HA-tag, was done as previously described (Morrison et al., 2007).

Protein Purification and Analysis

Standard protein techniques such as SDS-PAGE, Western blotting, and silver staining were followed. Recombinant GST-tagged domains were purified from E.coli using standard protocols (Espejo and Bedford, 2004). Rad53 antibody (Santa Cruz, 1:500) and Actin antibody (Milipore, 1:1000) were used in immunoblotting. Preparation of whole-cell extracts and FLAG-immunoaffinity purification were described in detail previously (Shen, 2004), except for the eluted complexes were further dialyzed against buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.1mM KCl, 2.5mM DTT, 2mM MgCl2, and protease inhibitors). Finally, small aliquots (11 μl) of complex were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Viability Measurements

Cells were grown to mid-log phase in YEPD and 5-fold serial dilutions of cultures were plated onto YEPD or HU plates. Plates were incubated for 2–4 days.

Co-IP Assay

Plasmid containing HA-tagged Rad53 was transformed into cells containing Flag-tagged INO80. Cells were grown to log phase and then treated with or without 0.05% MMS for 30 minutes. Same amount of treated cells and un-treated cells were collected, lysed by glass beads. Standard Co-IP protocol was followed using Dynabeads Protein G bound with anti-HA or anti-Flag antibodies. Co-immunoprecipited Rad53-HA or INO80-Flag were detected by Western blot using anti-HA antibody (Covance, 1:1000) or anti-Flag antibodies (Sigma, 1:2000).

Kinase Assay

Standard Kinase assays (15 μl) contained: 25mM HEPES pH 7.8, 125mM NaCl, 8mM MgCl2, 100ug/ml BSA, 5ug/ml Ethidium Bromide, 1mM DTT, 100μM ATP, and 1μl Rad53HA-beads (about 5 nM Rad53-HA) or whole cell extracts as indicated. Different amount (2 nM to 20 nM) of INO80 or INO80K737A complexes were added, and the assay was incubated at 30 °C for 1 hour. The reaction was terminated by addition of 5 μl of 4X SDS-PAGE loading buffer. The phosphorylated Rad53 was detected by Western blot using Rad53 antibodies (Santa Cruz, 1:500) or anti-HA antibodies (Covance, 1:1000).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Laura Denton, Sarah Adai, Chris Contreras, and Briana Dennehey for reading of the manuscript, and Francoise Ochsenbein (CNRS, France) for helpful suggestions. P.K. is supported by Odyssey postdoctoral program and the Theodore N. Law Endowment for Scientific achievements at The UT MD Anderson Cancer Center. Funding to Y.B. is provided by Odyssey fellowship and Epigenetic scholarship at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. M.T.B. is supported by funds from CPRIT (PR110471), and US National Institute of Health (DK062248), and X.S. is supported by funds and grants from the US National Cancer Institute (K22CA100017), American Cancer Society, the US National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM093104), Center for Cancer Epigenetics and the IRG program at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alcasabas AA, Osborn AJ, Bachant J, Hu F, Werler PJ, Bousset K, Furuya K, Diffley JF, Carr AM, Elledge SJ. Mrc1 transduces signals of DNA replication stress to activate Rad53. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:958–965. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Shen X. Chromatin remodeling in DNA double-strand break repair. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2007a;17:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Shen X. INO80 subfamily of chromatin remodeling complexes. Mutation research. 2007b;618:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espejo A, Bedford MT. Protein-domain microarrays. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;264:173–181. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-759-9:173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert CS, Green CM, Lowndes NF. Budding yeast Rad9 is an ATP-dependent Rad53 activating machine. Mol Cell. 2001;8:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00267-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbini E, Cesena D, Galbiati A, Lockhart A, Longhese MP. Interplays between ATM/Tel1 and ATR/Mec1 in sensing and signaling DNA double-strand breaks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2013;12:791–799. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: ten years after. Mol Cell. 2007;28:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heideker J, Lis ET, Romesberg FE. Phosphatases, DNA damage checkpoints and checkpoint deactivation. Cell cycle. 2007;6:3058–3064. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.24.5100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Lee GI, Van Doren SR, Walker JC. The FHA domain mediates phosphoprotein interactions. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 23):4143–4149. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.23.4143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi G, Shen X, Landry J, Wu WH, Sen S, Wu C. ATPdriven exchange of histone H2AZ variant catalyzed by SWR1 chromatin remodeling complex. Science. 2004;303:343–348. doi: 10.1126/science.1090701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AJ, Kim JA, Person MD, Highland J, Xiao J, Wehr TS, Hensley S, Bao Y, Shen J, Collins SR, et al. Mec1/Tel1 phosphorylation of the INO80 chromatin remodeling complex influences DNA damage checkpoint responses. Cell. 2007;130:499–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AJ, Shen X. Chromatin remodelling beyond transcription: the INO80 and SWR1 complexes. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2009;10:373–384. doi: 10.1038/nrm2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, Hur SK, Lee HS, Lee SA, Kwon J. The human Ino80 binds to microtubule via the E-hook of tubulin: implications for the role in spindle assembly. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;416:416–420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicioli A, Foiani M. Signal transduction: how rad53 kinase is activated. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R769–R771. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicioli A, Lucca C, Liberi G, Marini F, Lopes M, Plevani P, Romano A, Di Fiore PP, Foiani M. Activation of Rad53 kinase in response to DNA damage and its effect in modulating phosphorylation of the lagging strand DNA polymerase. Embo J. 1999;18:6561–6572. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt HC, Yaffe MB. Phospho-Ser/Thr-binding domains: navigating the cell cycle and DNA damage response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:563–580. doi: 10.1038/nrm3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogakou EP, Boon C, Redon C, Bonner WM. Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:905–916. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5858–5868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Y, Bachant J, Wang H, Hu F, Liu D, Tetzlaff M, Elledge SJ. Control of the DNA damage checkpoint by chk1 and rad53 protein kinases through distinct mechanisms. Science. 1999;286:1166–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapountzi V, Cote J. MYST-family histone acetyltransferases: beyond chromatin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:1147–1156. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0599-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MF, Duong JK, Sun Z, Morrow JS, Pradhan D, Stern DF. Rad9 phosphorylation sites couple Rad53 to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA damage checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1055–1065. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X. Preparation and analysis of the INO80 complex. Methods in enzymology. 2004;377:401–412. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)77026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Mizuguchi G, Hamiche A, Wu C. A chromatin remodelling complex involved in transcription and DNA processing. Nature. 2000;406:541–544. doi: 10.1038/35020123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Xiao H, Ranallo R, Wu WH, Wu C. Modulation of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes by inositol polyphosphates. Science. 2003;299:112–114. doi: 10.1126/science.1078068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Kachirskaia I, Yamaguchi H, West LE, Wen H, Wang EW, Dutta S, Appella E, Gozani O. Modulation of p53 function by SET8-mediated methylation at lysine 382. Mol Cell. 2007;27:636–646. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracker TH, Usui T, Petrini JH. Taking the time to make important decisions: the checkpoint effector kinases Chk1 and Chk2 and the DNA damage response. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh GW, Lowndes NF. Role of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad9 protein in sensing and responding to DNA damage. Biochemical Society transactions. 2003;31:242–246. doi: 10.1042/bst0310242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Attikum H, Gasser SM. Crosstalk between histone modifications during the DNA damage response. Trends in cell biology. 2009;19:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.