Abstract

Ocean acidification causes biodiversity loss, alters ecosystems, and may impact food security, as shells of small organisms dissolve easily in corrosive waters. There is a suggestion that photosynthetic organisms could mitigate ocean acidification on a local scale, through seagrass protection or seaweed cultivation, as net ecosystem organic production raises the saturation state of calcium carbonate making seawater less corrosive. Here, we used a natural gradient in calcium carbonate saturation, caused by shallow-water CO2 seeps in the Mediterranean Sea, to assess whether seaweed that is resistant to acidification (Padina pavonica) could prevent adverse effects of acidification on epiphytic foraminifera. We found a reduction in the number of species of foraminifera as calcium carbonate saturation state fell and that the assemblage shifted from one dominated by calcareous species at reference sites (pH ∼8.19) to one dominated by agglutinated foraminifera at elevated levels of CO2 (pH ∼7.71). It is expected that ocean acidification will result in changes in foraminiferal assemblage composition and agglutinated forms may become more prevalent. Although Padina did not prevent adverse effects of ocean acidification, high biomass stands of seagrass or seaweed farms might be more successful in protecting epiphytic foraminifera.

Keywords: Benthic foraminifera, blue carbon, coastal communities, ocean acidification, shallow-water CO2 seeps

Introduction

Ocean acidification is, primarily, caused by anthropogenic emissions of CO2. A third of these recent emissions have dissolved into water at the ocean surface causing mean pH to fall by 0.1 pH units since pre-industrial times and this is predicted to decrease by a further 0.3–0.4 units by the end of this century (IPCC 2014). These changes in seawater carbonate chemistry are detrimental to most of the organisms that have been studied so far, but benefit others, causing profound changes in coastal ecosystems (Hall-Spencer et al. 2008; Kroeker et al. 2013). The effects of ocean acidification are a major concern as rapid shoaling of the calcium carbonate saturation horizon is exposing vast areas of marine sediment to corrosive waters worldwide (Feely and Chen 1982; Olafsson et al. 2009).

The geological record shows that the present rate of ocean acidification is likely to be faster than at any time in the last 300 million years (Zachos et al. 2005; Hönisch et al. 2012). Foraminifera (single-celled protists) occur from coasts to the deep sea (Goldstein 1999) and some even live in freshwater, or terrestrial environments. Their fossil record dates back to the beginning of the paleozoic (Murray 1979) and provides precious insights into past fluctuations in seawater carbonate chemistry. Deep-sea foraminifera suffered extinctions during periods of high CO2 in the past, such as during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) (Hönisch et al. 2012).

Laboratory investigations have shown that the shell weight of planktonic foraminifera declines as seawater calcium carbonate saturation falls (Bijma et al. 1999). Spero et al. (1997) found that Orbulina universa d’Orbigny shell weight increased by 37% when grown at high vs. background calcium carbonate levels. Bernhard et al. (2009a,b) showed that deep-sea calcareous foraminifera are killed by direct exposure to injected CO2, whereas thecate and agglutinated species survive. Acidification of seawater with 1000 ppm CO2 caused shell dissolution in the shallow-water calcified foraminifera Haynesina germanica (Ehrenberg), and their ornamentation used for feeding was reduced and deformed (Khanna et al. 2013). Some laboratory experiments, however, have found calcareous foraminifera not to be negatively impacted by ocean acidification (Hikami et al. 2011; Vogel and Uthicke 2012), or the response to be complex, with an initial positive response, up to intermediate pCO2, followed by a negative response (Fujita et al. 2011; Keul et al. 2013). In a review of 26 studies that have examined foraminiferal response patterns to carbonate chemistry, Keul et al. (2013) found that three reported a positive response to increased pCO2 and three reported no effect.

Carbon dioxide seeps create gradients of calcium carbonate saturation that provide opportunities to examine the long-term effects of corrosive waters on calcified marine life (Boatta et al. 2013; Milazzo et al. 2014). There are steep reductions in species richness around CO2 seeps; calcified foraminifera are intolerant of chronic exposure to acidified waters in coastal sediments of the Mediterranean Sea (Dias et al. 2010) and off Papua New Guinea (Fabricius et al. 2011; Uthicke et al. 2013).

Geo-engineering options are being considered as the far-reaching effects of ocean acidification are predicted to impact food webs, biodiversity, aquaculture, and hence society (Williamson and Turley 2012). Seaweeds and seagrasses can thrive in waters with naturally high pCO2 (Martin et al. 2008; Porzio et al. 2011), so could potentially provide an ecologically important and cost-effective means for improving seawater conditions for sensitive organisms by consuming dissolved CO2 and raising local seawater pH (Gao and Mckinley 1994; Manzello et al. 2012; Chung et al. 2013; Hendriks et al. 2014). The primary production of those seagrasses and macroalgae that are carbon limited increases as CO2 levels rise (Connell and Russell 2010; Manzello et al. 2012). A blue carbon project has been established in South Korea, where natural and made-made marine communities are being used to remove CO2 in coastal regions. The higher the biomass of these plant communities, the more CO2 is drawn down (Chung et al. 2013).

Here, we assess whether a common Mediterranean seaweed (Padina pavonica (Linné) Thivy) can create local ocean acidification sanctuaries by providing refugia for calcification. This species was chosen as many heterokont algae, and Padina spp. in particular, are resilient to the effects of ocean acidification (Porzio et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2012). In addition, Padina is abundant and hosts calcified foraminiferal epiphytes at our study sites (Langer 1993). Although benthic foraminifera living within and on sediment are expected to be adversely affected by ocean acidification, epiphytic foraminifera may be protected from the detrimental effects of ocean acidification, as macroalgal photosynthesis raises seawater pH (Cornwall et al. 2013). Photosynthesis by macroalgae utilizes the dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) pool, usually in the form of  (Gao and Mckinley 1994). The surfaces of organisms have a microlayer (known as a diffusion boundary layer, DBL) that usually differs from the surrounding seawater chemistry (Hurd et al. 2011). Within the DBL, the chemistry is altered by metabolic processes, and in macroalgae, photosynthesis increases the pH in the daytime (Hurd et al. 2011; Cornwall et al. 2013). These DBLs are on the scale of micrometers to millimeters, but within macroalgal canopies, where there is reduced flow, larger concentration gradients (up to 68 mm) can develop (Cornwall et al. 2013).

(Gao and Mckinley 1994). The surfaces of organisms have a microlayer (known as a diffusion boundary layer, DBL) that usually differs from the surrounding seawater chemistry (Hurd et al. 2011). Within the DBL, the chemistry is altered by metabolic processes, and in macroalgae, photosynthesis increases the pH in the daytime (Hurd et al. 2011; Cornwall et al. 2013). These DBLs are on the scale of micrometers to millimeters, but within macroalgal canopies, where there is reduced flow, larger concentration gradients (up to 68 mm) can develop (Cornwall et al. 2013).

Although macroalgae raise pH during the day, at night, pH in the DBL may drop to ∼7.8 in slow water flow (Cornwall et al. 2013). The macroalgae will still respire, but there will be no photosynthesis in the dark. Thus, epiphytes can experience a wide pH range on a daily basis, which exceeds open water mean pH changes expected due to ocean acidification (Cornwall et al. 2013). Some foraminifera host algal symbionts which can affect the pH of the DBL around the foraminiferal test (Köhler-Rink and Kühl 2000). Köhler-Rink and Kühl (2000) found that under saturating light conditions photosynthetic activity of the endosymbiotic algae increased pH up to 8.6 at the test surface. In the dark, pH at the test surface was lowered relative to the ambient seawater of pH 8.2.

In laboratory experiments, it has been found that algal epiphytes can resist levels of acidification associated with pCO2 values of 1193 ± 166 μatm (Saderne and Wahl 2013). In situ experiments show that seagrass photosynthesis can enhance calcification of the calcareous red algae Hydrolithon sp. 5.8-fold (Semesi et al. 2009). There are limits, however, to the role that marine plants can play in buffering the effects of ocean acidification. Martin et al. (2008) found a dramatic reduction in calcareous epiphytes on seagrass blades as pH reduced below a mean pH 7.7 near to CO2 seeps off Ischia in the Mediterranean.

We test the hypothesis that the brown seaweed P. pavonica collected along a CO2 gradient off Vulcano Island, Italy (Fig.1), provides a refuge for benthic foraminifera along a gradient of overlying seawater acidification. Foraminifera play an important role in the Earth’s CO2/ budget (Lee and Anderson 1991; Langer et al. 1997), so their response to ocean acidification may have important consequences for inorganic carbon cycling. A major foraminiferal die-off may act as a negative feedback on atmospheric CO2 levels and lead to a reduction in globally precipitated calcium carbonate (Dissard et al. 2010). The foraminifera may reflect responses of other small calcified animals, such as larval bivalves; therefore, if macroalgae are found to work well in limiting the effects of ocean acidification, people who rely on shellfish fisheries and aquaculture could grow seaweed to mitigate the effects of ocean acidification.

budget (Lee and Anderson 1991; Langer et al. 1997), so their response to ocean acidification may have important consequences for inorganic carbon cycling. A major foraminiferal die-off may act as a negative feedback on atmospheric CO2 levels and lead to a reduction in globally precipitated calcium carbonate (Dissard et al. 2010). The foraminifera may reflect responses of other small calcified animals, such as larval bivalves; therefore, if macroalgae are found to work well in limiting the effects of ocean acidification, people who rely on shellfish fisheries and aquaculture could grow seaweed to mitigate the effects of ocean acidification.

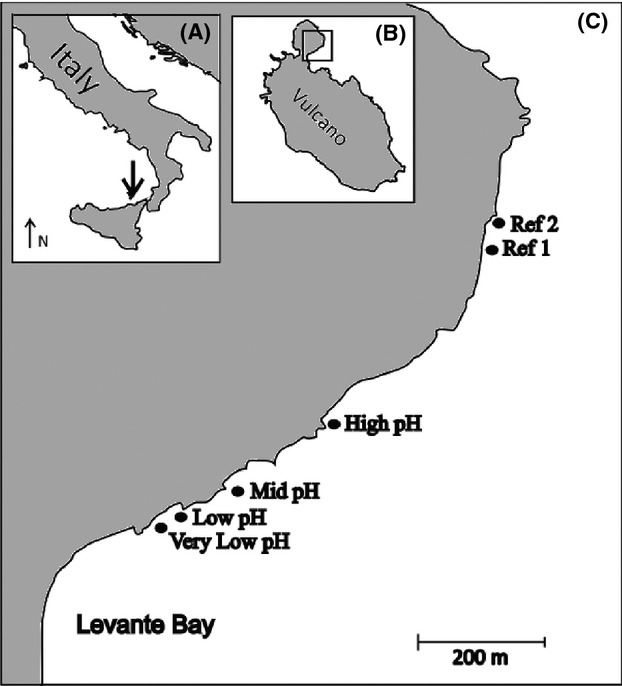

Figure 1.

Study area. (A) Italy with arrow marking Vulcano Island, part of the Aeolian islands chain, northeast Sicily, (B) Vulcano Island, (C) Location of sample sites. Very low pH is 38°25′9″ N, 14°57′38″E, Ref 2 is 38°25′20″N, 14°58′3″E.

Materials and Methods

Sampling took place near shallow submarine CO2 seeps in Levante Bay off Vulcano in the Mediterranean Sea, an island ca. 25 km northeast of Sicily (Fig.1). Our sites were chosen along part of a pH gradient where seawater was at ambient temperature and alkalinity, but was not affected by H2S (Boatta et al. 2013). Although variable, but small (∼400 ppm), amounts of H2S were found directly over the degassing area (Boatta et al. 2013), it should be noted that samples were not taken directly over the degassing area. Boatta et al. (2013) report that the sampling gradient used in the present study lacks toxic compounds such as H2S. Dissolved sulfide was below the detection limit (i.e., <15 μmol/kg) at 5 m distance from the degassing area (Boatta et al. 2013). Padina pavonica thalli were collected from six sites in May 2012 (Fig.1). Thalli were collected from approximately 1 m water depth, by cutting algal blades above the sediment surface and placing into labeled plastic sample bags underwater following the methods of Langer (1993). Five replicates were collected from each site. The thalli were placed in aluminum trays and left to air dry, then 2 g of dry thallus from each sample was randomly selected and examined under a stereo-binocular microscope. Epiphytic foraminifera were removed and placed on micropalaeontological picking slides. Foraminifera were identified to species level where this was possible using, for example, Cimerman and Langer (1991) and Milker and Schmiedl (2012), and then counted. The aim was to examine at least 300 individuals from each sample as 300 individuals are believed to be statistically representative of the whole sample (Pielou 1966). This, however, was not possible in all cases due to the low number of foraminifera found in the low-pH sites. It should be noted that as the thalli were dried, allogromiid foraminifera were not examined during this study.

Although the carbonate chemistry conditions along the pCO2 gradient at Vulcano have been reported extensively by others (Johnson et al. 2012, 2013; Boatta et al. 2013; Vizzini et al. 2013; Kerfahi et al. 2014; Milazzo et al. 2014), additional samples were collected during three separate fieldwork campaigns between May 2011 and May 2013. At each of the sample sites, pH, temperature, and salinity were recorded using a calibrated YSI (556 MPS) pH (NBS scale) meter. The NBS scale has a precision error of around ±0.05 units (Dickson et al. 2007), which was considered acceptable given the >1 unit fluctuations across the study gradient.

Three replicate total alkalinity (TA) samples were collected from each site and 0.02% by volume of mercuric chloride was added to each. The samples were sealed and stored in the dark until analysis using an AS-ALK2 Total Alkalinity Titrator (Apollo SciTech Inc., Bogart, GA, USA), calibrated using total alkalinity standards (Dickson Laboratory, batch 121, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, California, USA). The pH, TA, salinity, and temperature were used to calculate the remaining carbonate chemistry parameters using CO2SYS (Lewis and Wallace 1998).

Some foraminifera were examined under a JEOL JSM 5600 LV SEM with a digital imaging system to aid taxonomic identification and determine whether there was any dissolution. Individuals were mounted on aluminum SEM stubs and sputter coated in an Emitech K550 gold sputter coater. Dissolution was noted if foraminifera tests showed etching, pitting, fragmentation, or enlarged pores. Test walls were examined at a higher magnification (×4000) in 11 of the individuals.

Raw foraminifera community assemblage data were used to calculate Shannon–Wiener diversity, Fisher alpha, and Pielou’s evenness indices which were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) was used to examine assemblage shifts based on square root-transformed data to down-weight the contribution of dominant taxa. An ANOSIM test was conducted to test for similarities between sites, and a SIMPER test was used to determine discriminating species using PRIMER v6 (PRIMER-E Ltd., Ivybridge, UK).

Results

Seawater calcite saturation state ranged from a mean value of ∼5.29 at reference sites to ∼2.47 extending 200 m along a rocky shore at 0–5 m water depth (Boatta et al. 2013). Mean pHNBS ranged from 8.19 at the reference sites to 7.71 at the lowest pH site, which is closest to the seeps (Fig.2). The pH decreased across the gradient from reference sites to sample site very low pH (Table1) and was lower and more variable, near to the seeps.

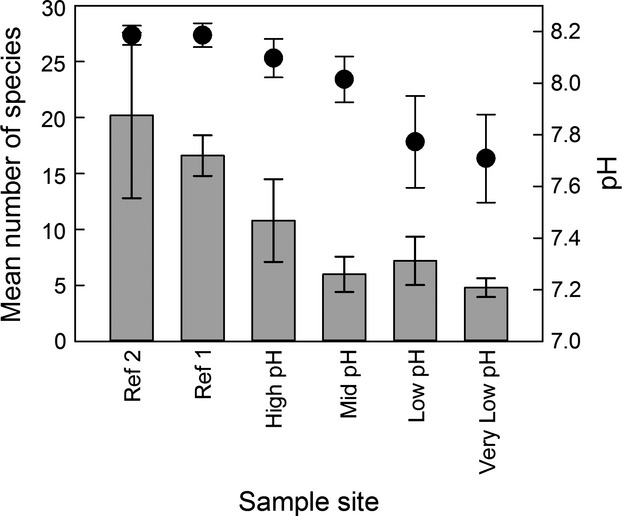

Figure 2.

Mean (±1 SD, n = 5) number of species (gray bars) of epiphytic foraminifera found on P. pavonica thalli off Vulcano CO2 seeps in May 2012 with mean (±1 SD, n = 8–11) pH (filled circles) between May 2011 and May 2013.

Table 1.

Seawater pH and associated carbonate chemistry parameters measured between May 2011 and May 2013 at six sample sites off Vulcano, Italy. Carbonate chemistry parameters were calculated from pHNBS and mean total alkalinity (TA) measurements at each site (n values for each are shown next to site names)

| Site | pH (NBS) | TA (μmol/kg SW) | pCO2 (μatm) |

(μmol/kg SW) (μmol/kg SW) |

(μmol/kg SW) (μmol/kg SW) |

ΩCalc | ΩArag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref 2(npH = 11, nTA = 7) | |||||||

| Min | 8.12 | 2320.5 | 396.3 | 1895.7 | 198.7 | 4.66 | 3.10 |

| Median | 8.17 | 2538.7 | 418.0 | 1973.4 | 216.6 | 5.05 | 3.29 |

| Max | 8.25 | 2607.2 | 643.8 | 2023.3 | 250.8 | 5.90 | 3.95 |

| Ref 1(npH = 10, nTA = 7) | |||||||

| Min | 8.12 | 2368.4 | 395.3 | 1906.4 | 193.6 | 4.54 | 3.02 |

| Median | 8.17 | 2554.6 | 423.1 | 1991.8 | 220.9 | 5.15 | 3.36 |

| Max | 8.25 | 2645.6 | 682.4 | 2061.6 | 256.5 | 6.01 | 4.06 |

| High pH(npH = 8, nTA = 7) | |||||||

| Min | 7.98 | 2368.4 | 444.9 | 2026.5 | 157.7 | 3.69 | 2.44 |

| Median | 8.15 | 2580.3 | 698.6 | 2034.8 | 210.7 | 4.91 | 3.20 |

| Max | 8.15 | 2702.5 | 1292.7 | 2166.5 | 215.7 | 5.12 | 3.49 |

| Mid-pH(npH = 8, nTA = 6) | |||||||

| Min | 7.90 | 2392.4 | 519.0 | 2042.7 | 136.9 | 3.23 | 2.17 |

| Median | 8.01 | 2639.8 | 750.7 | 2193.1 | 167.0 | 3.92 | 2.60 |

| Max | 8.18 | 2776.3 | 1317.9 | 2267.7 | 228.8 | 5.36 | 3.54 |

| Low pH(npH = 8, nTA = 7) | |||||||

| Min | 7.61 | 2454.8 | 770.3 | 2269.9 | 76.0 | 1.77 | 1.15 |

| Median | 7.78 | 2652.6 | 1676.6 | 2461.0 | 114.6 | 2.70 | 1.81 |

| Max | 8.06 | 3004.1 | 2092.1 | 2552.0 | 193.7 | 4.54 | 3.00 |

| Very Low pH(npH = 8, nTA = 7) | |||||||

| Min | 7.61 | 2405.5 | 615.3 | 2182.3 | 77.9 | 1.82 | 1.18 |

| Median | 7.67 | 2663.3 | 1831.9 | 2477.0 | 85.9 | 2.01 | 1.34 |

| Max | 8.11 | 2958.3 | 2658.6 | 2495.6 | 207.8 | 4.86 | 3.20 |

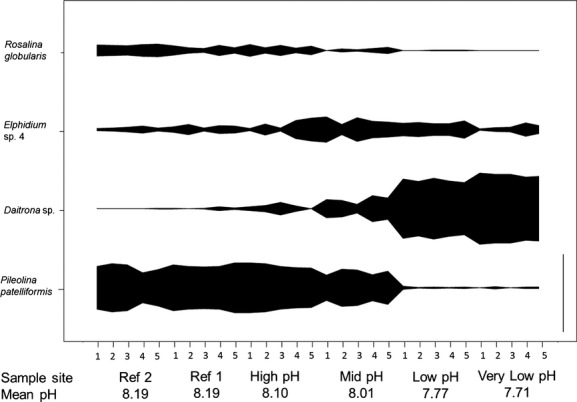

As in previous years (Johnson et al. 2012), dense stands of Padina pavonica characterized the rocky shore transect in May 2012. Epiphytic foraminifera were found on all 30 thalli examined with 3851 individuals counted during this study. We found a reduction in the number of species of epiphytic foraminifera along a calcium carbonate saturation gradient from reference sites (Ω ∼ 5.29) to high CO2 conditions (Ω ∼ 2.47) nearer to the seeps (Fig.2). The number of species ranged from 4 to 30 per replicate. Shannon–Wiener diversity ranged from 2.29 at the reference sites to 0.45 in samples collected from the most acidified site, with corresponding Fisher alpha and Pielou’s evenness indices of 10.07 to 0.88 and 0.67 to 0.28, respectively, as the most acidified samples were dominated by just a few species of foraminifera. The non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test revealed a statistically significant difference in the number of species between sites (P ≤ 0.001, H = 22.663, degrees of freedom = 5). The number of individuals per replicate ranged from 22 to 457 with the lowest number of individuals occurring at sites with intermediate pH. Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks revealed a statistically significant difference in the number of individuals between sites (P ≤ 0.001, H = 22.002, degrees of freedom = 5). The most abundant species was Pileolina patelliformis (Brady) with a total of 1541 individuals (40% of total) (Fig.3). The relative abundance of P. patelliformis decreased across the gradient from approximately 56.5% at one of the reference sites to 1.5% closest to the CO2 seeps. The next most abundant species was Daitrona sp. with 875 individuals (23% of total). The relative abundance of Daitrona sp. increased across the gradient from 0.3% at reference sites to 85.5% at high CO2. The assemblages were dominated by calcareous forms at reference sites (pH ∼8.19) and by agglutinated forms nearer to the seeps (pH ∼7.71). The dominant taxa in the low-pH conditions were Daitrona sp., which has an agglutinated test, and Elphidium spp.

Figure 3.

Relative abundance (%) of the four most abundant types of epiphytic foraminifera found on 2 g of dried P. pavonica samples at Vulcano in May 2012. Numbers 1–5 are replicate numbers. The vertical scale bar on the bottom right-hand side of the plot represents a relative abundance of 100%.

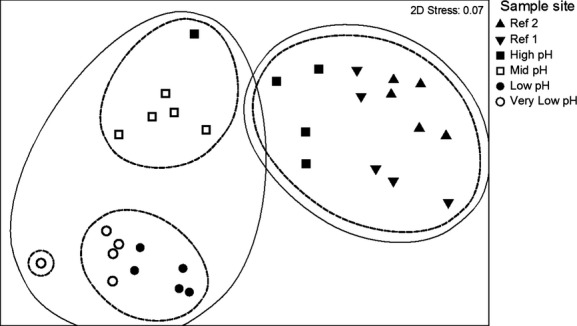

Foraminiferal assemblages were similar at sample sites with similar CO2 levels. The sample sites cluster into four distinct groups on an nMDS plot, those from the reference sites and highest pH areas (Ref 2, Ref 1 and high pH), those from the mid-pH area with one sample from high pH, those from lowest pH areas (low pH and very low pH), and one sample from very low pH which plots as a singlet (Fig.4). One-way ANOSIM test also showed significant site differences in the assemblage (Global R statistic = 0.837, P = 0.001). Pairwise tests show which sites were responsible for the differences. The sites that did not have a statistically significant difference in assemblage at the 0.01 significance level were as follows: Ref 2 and Ref 1; Ref 1 and high pH; and high pH and mid-pH. The assemblage of foraminifera living on Padina seaweed surfaces was similar between the two reference sites, a reference site and the high-pH site and the high-pH and mid-pH site. SIMPER revealed that the five taxa that contributed most to dissimilarity between sample sites were as follows: Pileolina patelliformis, plastogamous pairs of P. patelliformis, Daitrona sp., Rosalina globularis d’Orbigny, and Peneroplis pertusus (Forskål).

Figure 4.

Similarities between epiphytic foraminiferal assemblages growing on P. pavonica thalli in 30 samples collected in May 2012 along a CO2 gradient off Vulcano. The circles group samples at the 40 (solid) and 60 (dashed) percent similarity levels.

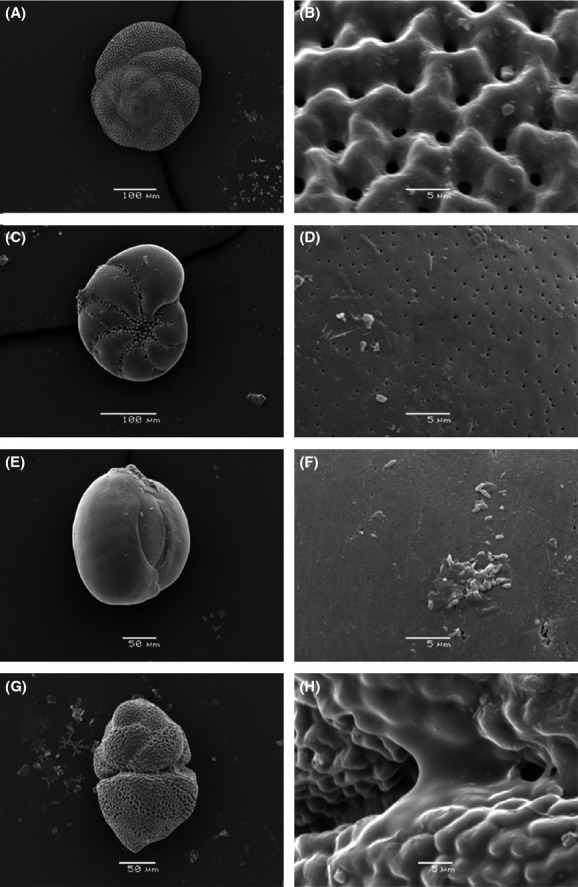

In total, 46 individuals were examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (24 from Ref 2, eight from Ref 1, three from high pH, three from mid-pH, six from low pH, and two from very low pH). Of the 11 that were examined at a higher magnification (×4000), only one showed signs of dissolution. This specimen, identified as Miliolinella dilatata (d’Orbigny), showed signs of surface pitting and was collected from the reference site, Ref 2. There were no deformities (such as abnormally shaped chambers) in any of the 46 individuals examined under the SEM (Fig.5), although there were a very small number of individuals (ten individuals, amounting to <1% of the total assemblage) that were noted to have deformities when examined under the light microscope.

Figure 5.

Wall structure of selected epiphytic foraminifera collected on P. pavonica thalli off Vulcano in May 2012. (A) Pileolina patelliformis from site Ref 2 (pH ∼8.19), (B) wall detail of final chamber; (C) Haynesina depressula from site Ref 1 (pH ∼8.19), (D) wall detail of final chamber; (E) Miliolinella subrotunda from site Ref 2 (pH ∼8.19), (F) wall detail of final chamber; and (G) a plastogamous pair of P. patelliformis from site Ref 2 (pH ∼8.19), (H) detail of the join between the two specimens.

Discussion

As photosynthetic activity of marine plants and algae increases seawater pH (Semesi et al. 2009; Manzello et al. 2012; Hendriks et al. 2014), we predicted that seaweed growth would protect small calcareous organisms from acidified conditions near to CO2 seeps by raising calcium carbonate saturation state in the DBL. In fact, we found major losses of calcified foraminifera in high CO2 conditions. Saderne and Wahl (2013) found that fucoid algal epiphytes were resistant to pCO2 levels ca. 1200 μatm, but at around 3150 μatm, the tube worms (Spirorbis spirorbis) had reduced growth and settlement rates, although calcified (Electra pilosa) and non-calcified (Alcyonidium hirsutum) bryozoans were not impacted. They also argue that photosynthesis of the fucoid algae modulates calcification of small epiphytes inhabiting the algal DBL.

The degree of buffering will depend on hydrodynamics and structural characters of seagrasses or macroalgal stand (Cornwall et al. 2014; Hendriks et al. 2014). When photosynthetic biomass is high, these habitats can experience pH values above that of ambient seawater, enhancing calcification rates of associated organisms (Semesi et al. 2009). The standing stock of P. pavonica was clearly insufficient at Vulcano to allow a similar foraminiferal community to develop at the low-pH sites compared to the reference sites. Padina pavonica may buffer the pH in the DBL during the daytime, but algal respiration at night causes large daily fluctuations in pH (Cornwall et al. 2013) and it may be periodic exposure to corrosive water that excluded some of the small calcified organisms. Light levels are expected to have a strong influence on pH in the DBL (Cornwall et al. 2013). Epiphytes already experience a large daily range in pH due to light–dark cycles and fluctuations in light levels (Cornwall et al. 2013). This large daily variation may make them more resilient to future changes in pH due to ocean acidification (Cornwall et al. 2013).

The present study found a shift in the community assemblage of epiphytic foraminifera as pH decreased along a natural CO2 gradient from one dominated by Pileolina patelliformis and other calcareous taxa to one dominated by the agglutinated Daitrona sp. This shift occurred where mean pH reduced from ∼ 8.01 to ∼ 7.77 with a change in the mean ΩCalc from 4.06 to 2.89. Distinct shifts in community assemblages have been identified before at other shallow-water CO2 seeps (Hall-Spencer et al. 2008; Dias et al. 2010; Fabricius et al. 2011). An ecological shift was found at a mean pH of 7.8–7.9 at Ischia (Hall-Spencer et al. 2008), and no calcareous foraminifera were found below a mean pH of ∼7.6 at Ischia, where agglutinated foraminifera dominated the foraminiferal assemblage (Dias et al. 2010). At seeps off Papua New Guinea, no foraminifera were found at sites with a mean pH below ∼7.9, and even in locations with a higher pH (∼8.0), many foraminiferal tests were corroded or pitted (Fabricius et al. 2011).

In this study, only two miliolid (porcelaneous) foraminifera were found at the lowest pH site where there was a large increase in the proportion of agglutinated foraminifera. Miliolids generally have high-magnesium calcite tests (Bentov and Erez 2006) which is more soluble than aragonite (Morse et al. 2006) making them even more vulnerable to the effects of ocean acidification. Agglutinated foraminifera are expected to be more resilient to ocean acidification, and may even benefit from the loss of calcified competitors, as they do not produce calcium carbonate tests. The materials used to construct their test, however, may still be cemented together by calcite (Sen Gupta 1999). Daitrona sp., which was the only agglutinated taxon present in our samples, attach sediment particles to a proteinaceous or non-calcite matrix (Sen Gupta 1999). Elphidium spp. were also common on P. pavonica in high CO2 conditions. The presence of Elphidium spp. in the low calcite saturation area suggests that they were able to calcify and maintain their calcium carbonate tests, although a small percentage (1%) was deformed. This taxon is stress tolerant (Alve 1995; Frontalini and Coccioni 2008) and has low-magnesium calcite tests (below 4 mol % MgCO3) (Bentov and Erez 2006), which may explain their ability to survive in high CO2, low calcite saturation conditions.

Although it is possible that specimens had died, but remained on the thalli after drying (Poag 1982), any epiphytic foraminifera that were attached to the thalli must have been living recently in order to attach themselves. Any that had been washed onto the thalli as dead individuals are likely to have been washed off during collection of the samples. Langer (1993) counted individuals that were still attached to the thalli as living. Padina pavonica is thought to have a perennial life cycle, but dies back in the winter and, therefore, any attached foraminifera cannot have been on the thalli for longer than 1 year, and the CO2 gradient off Vulcano is known to remain consistent across years (e.g., Johnson et al. 2012; Boatta et al. 2013) so any foraminifera on the thalli are expected to have been subjected to the same carbonate chemistry conditions as recorded in this study.

Padina pavonica may provide refugia from ocean acidification for certain calcified foraminifera, but the majority were unable to tolerate the most acidified conditions. Dense seagrass beds or seaweed farms may mitigate ocean acidification if the carbon produced by photosynthesis is not released back into the water column. In an examination of epibionts (coralline algae, bryozoans, and hydrozoans) on seagrass blades, Martin et al. (2008) also found a dramatic reduction in the amount of calcareous epiphytes as pH reduced, close to shallow-water CO2 seeps at Ischia. Below a mean pH of 7.7, bryozoans were the only calcareous epibionts present on the seagrass blades. This indicates that seagrass meadows cannot protect the full suite of calcareous epibionts from the effects of low-pH conditions.

Vizzini et al. (2013) warn against relating biological changes at volcanic CO2 seeps solely to pH, and it is likely that multiple drivers were affecting foraminiferal community composition across the sampling gradient. Vizzini et al. (2013) found trace element enrichment along the pCO2 gradient at Vulcano and warn that this could be a driver of any biological changes seen. Although this is a possibility, the finding of similar ecological patterns from studies at other CO2 seeps suggests that CO2 is likely to be the main environmental driver at this site. Boatta et al. (2013) argue that the northern part of the bay (the area from which samples were taken in the present study) is well suited to studies of the effects of increased CO2 levels.

We found a reduction in the number of species of epiphytic foraminifera on the brown seaweed P. pavonica along a shallow-water pCO2 gradient. There was an assemblage shift from domination by calcareous taxa at reference sites (pCO2 ∼ 470 μatm) to domination by agglutinated taxa near to the seeps (pCO2 ∼ 1860 μatm). The hypothesis that algal surfaces would provide a refugia for assemblages of calcified organisms along a gradient of overlying seawater acidification was not supported. It is expected that ocean acidification will result in changes in foraminiferal community composition and agglutinated forms may become more prevalent.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank G. Suaria for his help with sample collection, M. Palmer for her help with TA analysis, and G. Harper, P. Bond, and R. Moate for their help with the SEM. L.R.P. is carrying out a PhD supported by the UK Ocean Acidification research programme, co-funded by NERC, Defra and DECC. This article contributes to the EU FP7 project on “Mediterranean Sea Acidification under a changing climate” (MedSeA grant agreement no. 265103) with additional funding for J.M.H-S. from the Save Our Seas Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Alve E. Benthic foraminiferal responses to estuarine pollution: a review. J. Foramin. Res. 1995;25:190–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bentov S. Erez J. Impact of biomineralization processes on the Mg content of foraminiferal shells: a biological perspective. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2006;7:Q01P08. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard J, Barry J, Buck K. Starczak V. Impact of intentionally injected carbon dioxide hydrate on deep sea benthic foraminiferal survival. Glob. Change Biol. 2009a;15:2078–2088. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard J, Mollo-Christensen E, Eisenkolb N. Starczak VR. Tolerance of allogromiid Foraminifera to severely elevated carbon dioxide concentrations: implications to future ecosystem functioning and paleoceanographic interpretations. Global Planet. Change. 2009b;65:107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bijma J, Spero H. Lea D. Reassessing foraminiferal stable isotope geochemistry: impact of the oceanic carbonate system (experimental results) In: Fischer G, Wefer G, editors; Use of proxies in paleoceanography: examples from the South Atlantic. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1999. pp. 489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Boatta F, D’Alessandro W, Gagliano AL, Liotta M, Milazzo M, Rodolfo-Metalpa R, et al. Geochemical survey of Levante Bay, Vulcano Island (Italy), a natural laboratory for the study of ocean acidification. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013;73:485–494. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung IK, Oak JH, Lee JA, Shin JA, Kim JG. Park K-S. Installing kelp forests/seaweed beds for mitigation and adaptation against global warming: Korean Project Overview. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2013;70:1038–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Cimerman F. Langer MR. 1991. Mediterranean Foraminifera, pp. 93 Ljubljana, Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti Ljubljana.

- Connell SD. Russell BD. The direct effects of increasing CO2 and temperature on non-calcifying organisms: increasing the potential for phase shifts in kelp forests. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2010;277:1409–1415. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall CE, Hepburn CD, Pilditch CA. Hurd CL. Concentration boundary layers around complex assemblages of macroalgae: implications for the effects of ocean acidification on understory coralline algae. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2013;58:121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall CE, Boyd PW, Mcgraw CM, Hepburn CD, Pilditch CA, Morris JN, et al. Diffusion Boundary Layers Ameliorate the Negative Effects of Ocean Acidification on the Temperate Coralline Macroalga Arthrocardia corymbosa. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias BB, Hart MB, Smart CW. Hall-Spencer JM. Modern seawater acidification: the response of foraminifera to high-CO2 conditions in the Mediterranean Sea. J. Geol. Soc. London. 2010;167:843–846. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson AG, Sabine CL. Christian JR. 2007. In: PICES special publication. pp. 175, IPCC Report number 8, and Guide to best practices for ocean CO2 measurements.

- Dissard D, Nehrke G, Reichart G. Bijma J. Impact of seawater pCO2 on calcification and Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca ratios in benthic foraminifera calcite: results from culturing experiments with Ammonia tepida. Biogeosciences. 2010;7:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius KE, Langdon C, Uthicke S, Humphrey C, Noonan S, De’ath G, et al. Losers and winners in coral reefs acclimatized to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2011;1:165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Feely RA. Chen CTA. The effect of excess CO2 on the calculated calcite and aragonite saturation horizons in the northeast Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1982;9:1294–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Frontalini F. Coccioni R. Benthic foraminifera for heavy metal pollution monitoring: a case study from the central Adriatic Sea coast of Italy. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2008;76:404–417. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K, Hikami M, Suzuki A, Kuroyanagi A. Kawahata H. Effects of ocean acidification on calcification of symbiont-bearing reef foraminifers. Biogeosciences. 2011;8:2089–2098. [Google Scholar]

- Gao K. Mckinley KR. Use of macroalgae for marine biomass production and CO2 remediation: a review. J. Appl. Phycol. 1994;6:45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein ST. Foraminifera: a biological overview. In: Sen Gupta BK, editor. Modern foraminifera. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Spencer JM, Rodolfo-Metalpa R, Martin S, Ransome E, Fine M, Turner SM, et al. Volcanic carbon dioxide vents show ecosystem effects of ocean acidification. Nature. 2008;454:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature07051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks I, Olsen Y, Ramajo L, Basso L, Steckbauer A, Moore T, et al. Photosynthetic activity buffers ocean acidification in seagrass meadows. Biogeosciences. 2014;11:333–346. [Google Scholar]

- Hikami M, Ushie H, Irie T, Fujita K, Kuroyanagi A, Sakai K, et al. Contrasting calcification responses to ocean acidification between two reef foraminifers harboring different algal symbionts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011;38:L19601. [Google Scholar]

- Hönisch B, Ridgwell A, Schmidt DN, Thomas E, Gibbs SJ, Sluijs A, et al. The Geological Record of Ocean Acidification. Science. 2012;335:1058–1063. doi: 10.1126/science.1208277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd CL, Cornwall CE, Currie K, Hepburn CD, Mcgraw CM, Hunter KA, et al. Metabolically induced pH fluctuations by some coastal calcifiers exceed projected 22nd century ocean acidification: a mechanism for differential susceptibility? Glob. Change Biol. 2011;17:3254–3262. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability - IPCC Working Group II Contribution to AR5. Cambridge.

- Johnson VR, Russell BD, Fabricius KE, Brownlee C. Hall-Spencer JM. Temperate and tropical brown macroalgae thrive, despite decalcification, along natural CO2 gradients. Glob. Change Biol. 2012;18:2792–2803. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V, Brownlee C, Rickaby R, Graziano M, Milazzo M. Hall-Spencer J. Responses of marine benthic microalgae to elevated CO2. Mar. Biol. 2013;160:1813–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Kerfahi D, Hall-Spencer J, Tripathi B, Milazzo M, Lee J. Adams J. Shallow water marine sediment bacterial community shifts along a natural CO2 gradient in the Mediterranean Sea off Vulcano, Italy. Microb. Ecol. 2014;67:819–828. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keul N, Langer G, Nooijer L. Bijma J. Effect of ocean acidification on the benthic foraminifera Ammonia sp. is caused by a decrease in carbonate ion concentration. Biogeosciences. 2013;10:6185–6198. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna N, Godbold JA, Austin WE. Paterson DM. The impact of ocean acidification on the functional morphology of foraminifera. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler-Rink S. Kühl M. Microsensor studies of photosynthesis and respiration in larger symbiotic foraminifera. I The physico-chemical microenvironment of Marginopora vertebralis Amphistegina lobifera and Amphisorus hemprichii. Mar. Biol. 2000;137:473–486. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeker KJ, Kordas RL, Crim R, Hendriks IE, Ramajo L, Singh GS, et al. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms: quantifying sensitivities and interaction with warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2013;19:1884–1896. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer MR. Epiphytic foraminifera. Mar. Micropaleontol. 1993;20:235–265. [Google Scholar]

- Langer MR, Silk MT. Lipps JH. Global ocean carbonate and carbon dioxide production; the role of reef Foraminifera. J. Foramin. Res. 1997;27:271–277. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ. Anderson OR. Biology of foraminifera. In: Lee JJ, Anderson OR, editors; Biology of foraminifera. London: Academic Press Limited; 1991. pp. 157–220. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis E. Wallace DWR. 1998. ORNL/CDIAC-105. Oak Ridge. Tennessee., Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, US Dept. of Energy, and Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations.

- Manzello DP, Enochs IC, Melo N, Gledhill DK. Johns EM. Ocean acidification refugia of the Florida reef tract. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, Rodolfo-Metalpa R, Ransome E, Rowley S, Buia M, Gattuso J, et al. Effects of naturally acidified seawater on seagrass calcareous epibionts. Biol. Lett. 2008;4:689. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milazzo M, Rodolfo-Metalpa R, San Chan VB, Fine M, Alessi C, Thiyagarajan V, et al. Ocean acidification impairs vermetid reef recruitment. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4189. doi: 10.1038/srep04189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milker Y. Schmiedl G. A taxonomic guide to modern benthic shelf foraminifera of the western Mediterranean Sea. Palaeontol. Electronica. 2012;15:1–134. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JW, Andersson AJ. Mackenzie FT. Initial responses of carbonate-rich shelf sediments to rising atmospheric pCO2 and “ocean acidification”: role of high Mg-calcites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2006;70:5814–5830. [Google Scholar]

- Murray JW. British Nearshore Foraminiferids: keys and notes for the identification of the species. London: Academic Press; 1979. p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Olafsson J, Olafsdottir S, Benoit-Cattin A, Danielsen M, Arnarson T. Takahashi T. Rate of Iceland Sea acidification from time series measurements. Biogeosciences. 2009;6:2661–2668. [Google Scholar]

- Pielou E. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. J. Theor. Biol. 1966;13:131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Poag CW. Environmental implications of test–to–substrate attachment among some modern sublittoral foraminifera. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1982;93:252–268. [Google Scholar]

- Porzio L, Buia MC. Hall-Spencer JM. Effects of ocean acidification on macroalgal communities. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2011;400:278–287. [Google Scholar]

- Saderne V. Wahl M. Differential responses of calcifying and non-calcifying epibionts of a brown macroalga to present-day and future upwelling pCO2. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semesi IS, Beer S. Björk M. Seagrass photosynthesis controls rates of calcification and photosynthesis of calcareous macroalgae in a tropical seagrass meadow. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009;382:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sen Gupta BK. Systematics of modern Foraminifera. In: Sen Gupta BK, editor. Modern foraminifera. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Spero H, Bijma J, Lea D. Bemis B. Effect of seawater carbonate concentration on foraminiferal carbon and oxygen isotopes. Nature. 1997;390:497–500. [Google Scholar]

- Uthicke S, Momigliano P. Fabricius K. High risk of extinction of benthic foraminifera in this century due to ocean acidification. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1769. [Google Scholar]

- Vizzini S, Di Leonardo R, Costa V, Tramati C, Luzzu F. Mazzola A. Trace element bias in the use of CO2 -vents as analogues for low-pH environments: implications for contamination levels in acidified oceans. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2013;134:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel N. Uthicke S. Calcification and photobiology in symbiont-bearing benthic foraminifera and responses to a high CO2 environment. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2012;424:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson P. Turley C. Ocean acidification in a geoengineering context. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 2012;370:4317–4342. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2012.0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachos JC, Röhl U, Schellenberg SA, Sluijs A, Hodell DA, Kelly DC, et al. Rapid acidification of the ocean during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum. Science. 2005;308:1611–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.1109004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]