Summary

Cigarette smoking is a leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States. Although public policies have resulted in a decreased number of new smokers, smoking rates remain stubbornly high in certain demographics with 20% of all American middle aged men smoking. In addition to the well-established harmful effects of smoking (i.e coronary artery disease and lung cancer), the past three decades have led to a compendium of evidence being compiled into the development of a relationship between cigarette smoking and erectile dysfunction. The main physiological mechanism that appears to be affected includes the nitric oxide signal transduction pathway. This review details the recent literature linking cigarette smoking to erectile dysfunction, epidemiological associations, dose-dependency and the effects of smoking cessation on improving erectile quality.

Keywords: Erectile dysfunction, nitric oxide, smoking, smoking cessation, vascular disease

INTRODUCTION

Erectile dysfunction is clinically defined as the persistent, or recurrent inability to achieve/maintain an erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual performance (NIH Consensus Conference, 1993). It is a far-reaching diagnosis with 20% of all men and up to 52% of males aged 40–70 years being classified as suffering from varying degrees of ED (Feldman et al., 1994). Increasing age has long been the strongest association with the disease process. Because the physiology of erection is heavily dependent on vascular changes, many of the known cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes have been associated with the development of erectile dysfunction (Miner et al., 2012). Cigarette smoking can lead to cardiovascular dysfunction and is now established to be an independent risk factor for the development of erectile dysfunction, a more ominous form vascular disease. Is it possible that quitting smoking can reverse some of the processes that contribute to ED? If so, this should become a focused treatment goal in the field of sexual medicine, irrespective of the more global health benefits obtained following smoking cessation.

PHYSIOLOGY OF ERECTILE FUNCTION

The penile corpora cavernosa are specialised spongy vascular structures encapsulated by the envelope of the tunica albuginea. Penile erection requires adequate relaxation of cavernous smooth muscles and dilation of penile arterioles allowing inflow, and subsequent trapping of blood, within the erectile tissue (Dean & Lue, 2005). This process is dependent upon the parasympathetic nervous system, which induces smooth muscle relaxation allowing arterial pressure blood into the corpus cavernosum via the actions of nitric oxide (NO) (Rajfer et al., 1992). NO is generated by three nitric oxide synthase (NOS) enzyme isoforms: neuronal, endothelial and inducible. The neuronal isoform appears to be the primary mediator of physiologic erection (Burnett, 1995). Neuronal NO is believed to induce erections while shear stress also propogates the erectile response via endothelial NO. Regardless of source, NO modulates smooth muscle cyclic GMP to induce relaxation in a paracrine fashion. Vascular relaxation in turn allows arterial blood to fill the corpora which, by distention, creates a venous seal to maintain erection.

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS ASSOCIATING SMOKING WITH ED

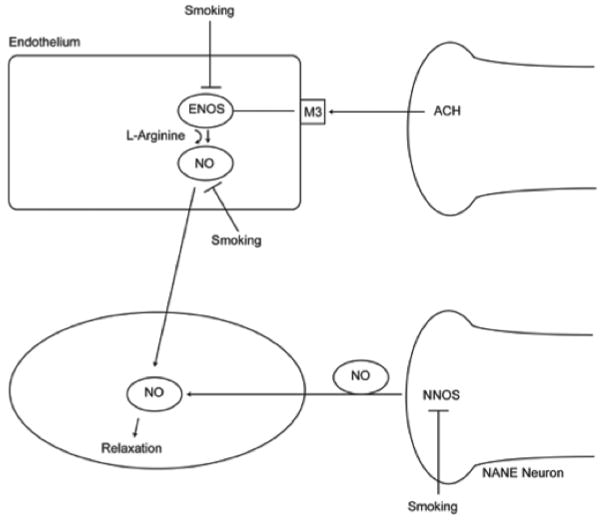

As mentioned above, the most well understood signal transduction mechanism underlying ED involves the NO pathway. With regard to smoking, both constituent NOS isoforms, the endothelial and neuronal variants, have been shown to be affected by cigarette smoke. Neuronal NOS activity by non-adrenergic non-cholinergic neurons is known to be decreased in both in vitro and in vivo models of smoking. (Xie et al., 1997) Components of burned, but not unburned tobacco, are in part responsible for the loss of neuronal NO through enzymatic blockade (Demady et al., 2003). It has been well-established in the vascular literature that cigarette smoke damages the endothelium and impairs eNOS mediated vasodilation (Celermajer et al., 1993; Butler et al., 2001).

Furthermore, in addition to cigarettes’ effect on enzymatic synthesis, superoxide anions produced by the metabolites from smoke directly decrease the level of free NO in the corpora cavernosa. This is partially mediated via activation of the NADH oxidase enzyme family (Orosz et al., 2007). Superoxide anions are increased in smokers and their presence shunts NO into a peroxynitrite pathway that lessens the vasoactive availabilty of NO (Peluffo et al., 2009).

The Rho-associated kinase (ROK), which regulates sensitivity to calcium contractility in the smooth muscle cell, is known to maintain the flaccid state and, as such, ROK-inhibitors can be theorised to induce erection (Mills et al., 2001). Intracellular NO functions to inhibit ROK allowing for vasodilation. Similarly, decreases in NO levels secondary to smoking, disinhibit ROK and act to further worsen ED (Chitaley et al., 2001). Furthermore, smokers have decereased ROK activity in peripheral leukocytes correlating to poor nitroglycerin vasodilation further hinting at a connection between ROK signalling and smoking (Hidaka et al., 2010).

Smoking also causes intrinsic damage to vessels preventing elastic dilation despite strong paracrine singals. Smoking alters the elastin of the extracellular matrix and induces calcification of medial elastic fibers producing arterial stiffness (Guo et al., 2006).

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN ED AND SMOKING

There have been numerous cross-sectional studies that have established a correlation between cigarette smoking and ED (Austoni et al., 2005; Kupelian et al., 2007; Chew et al., 2009; Ghalayini et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2012). The studies have included populations from China, the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas. Each study exhibited a variable baseline smoking prevalence. The odds ratio of smokers with ED has ranged between 1.4 and 3.1 with statistically significant confidence intervals in the vast majority of these studies. Typically, populations were selected to minimise other known causes of ED like psychotropic medications and prostate cancer due to treatment effects. In a specific cohort of young men <40 years of age, smoking was a significant risk factor for ED. In these men, the multivariate analysis did not show significance in other vascular risk factors strongly indicating a role for smoking in the pathogenesis of ED in younger men (Elbendary et al., 2009). While the majority of these studies accounted for other vascular risk factors (i.e. age, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes), it was difficult to determine significance of any isolated risk factors since many existed together and were impossible to separate.

To address the inherent bias in cross-sectional studies, a series of long-term cohorts were created in the 1990s to determine possible links between smoking and ED. In the Male Health Professionals Study, of the 22,086 men without baseline ED, the relative risk that smokers developed ED over a follow up of 14 years was 1.4 (95% CI 1.3–1.6). (Bacon et al., 2006). Likewise in Minnesota cohort, the odds ratio of smokers to develop ED was 1.42 after adjusting for age (95%CI 1.00–2.02). The strength of the association was greatest in men under the age of 70 years and this association decreased with progressively older age groups. The investigators felt this may have been due to survivorship bias or the exclusion of men from the study who had undergone prostate surgery or who had prostate cancer (Gades et al., 2005). The Massachusetts Male Aging Study followed 513 middle-aged men with good erectile funciton and excluded diabetics and patients with baseline cardiac disease. Cigarette smokers were again found to have a risk ratio of 1.97 (95% CI 1.07–3.63) to develop ED adjusted for age and hypertensive medication.

In Finland, a cohort of 1130 men aged 50–70 were followed 10 years in a fashion similar to that done in the Massachuseets Male Health Study and Olmstead County survey. This study produced an odds-ratio of 1.4 that, while similar to that of the two aforementioned cohorts, did not reach statistical significance (95% CI 0.9–2.2) (Shiri et al., 2005). Further analysis found that smokers who developped vascular disease had three times the risk of developing ED compared to non-smokers without vascular disease. (RR 3.2, 1.3–7.5). In contrast, smokers without vascular disease had no increased risk of ED (RR 1.0 CI 0.5–1.8) (Shiri et al., 2006). This data has also been the subject of a recent systematic review which compiled 8 case-control and cohort studies composed of 28,586 men (the majority of which are from the Male Health Professions Study) creating a pooled OR of 1.81 (95% CI 1.34–2.44) for smokers having increased risk of developing erectile dysfunction (Cao et al., 2013).

SMOKING EFFECTS ON ED ARE DOSE-DEPENDENT

Cigarette smoking has been suggested to act with dose-dependency as a risk-factor for heart disease as well as ED. In subgroup analysis of other larger studies, odds ratios of patients who developed ED showed a significant difference when men smoked greater than 10 cigarettes per day (Austoni et al., 2005). Among smokers, a positive but non-significant trend towards increase ED occurred in relation to daily cigarette intake (Chew et al., 2009).

In a younger, less comorbid population, heavy smokers (>20 cigarettes/day) had doubled the likelihood of severe ED compared to those who smoked less (Natali et al., 2005). Others have also noted that cumulative smoking history was also a risk factor for ED. For example, cumulative indices such as pack-years were related to higher risk of ED. In this instance, Gades et al. (2005), found that a 29 pack-year history was resposible for a signficantly increased risk for ED compared to a less than 12 pack years history which carried with it the same risk as a non-smoker. In similar findings, the Boston Area Community Health Survey found that it was only at a threshold of 20 pack-years where the OR for developing ED became significant (Kupelian et al., 2007). However, an earlier Vietnam Experience Study did not show such a dose-relationship (Mannino et al., 1994).

Overall, it appears that the cumulative dose of cigarette exposure does predict for an odds of developing ED. Examining the severity of the ED, current evidence appears to suggest that heavy smoking causes more severe ED that appears to be not reversible following smoking cessation.

SMOKING AND EFFECTS ON OTHER COMORBIDITIES IN MEN WITH ED

Cigarette smoking is also known to affect numerous other co-morbidites associated with ED. For example, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease are known to affect erectile function by decreasing penile perfusion pressures resulting in increased time to maximal erection and decreased rigidity during erection (Shabsigh et al., 1991; Sullivan et al., 1999). Cigarette smoking is associated with arteriogenic ED and is a component of the general process of atherosclerosis (Shabsigh et al., 1991; Sullivan et al., 1999). Arterio-insufficiency also hinders erectile function by decreasing penile perfusion pressures resulting in increased times to maximal erection and decreased rigidity during erection (Dean & Lue, 2005).

Diabetes also contributes to ED through both microvascular and macrovascular damage (Maiorino et al., 2014). Studies have shown that >50% of diabetics have some degree of ED (Giuliano et al., 2004; Thorve et al., 2011). Furthermore, men with diabetes have a three fold increase in risk for developing ED (Feldman et al., 1994). Among a group of 51,464 middle-aged and elderly Chinese men, smokers were found to have a hazard ratio of 1.25 with regars to developing type 2 diabetes compared to non smokers (Shi et al., 2013). As such, not only does cigarette smoking directly impact the physiologic mechanisms of erectile function, but it also contributes to the development of other medical conditions independently associated with ED.

EFFECTS OF SMOKING CESSATION ON ERECTILE FUNCTION

The current literature has yet to reach a consensus as to the magnitude of the benefits for smoking cessation specifically with regards to ED. Indeed, in multiple cross-sectional studies, former smokers (defined as having quit smoking >1 year prior to the study), have an increased risk of suffering from any form of ED compoared to men who have never smoked (Austoni et al., 2005; Gades et al., 2005; Bacon et al., 2006). Former smokers have also been shown to have increased risk compared to current smokers, even when adjusted for age (Ghalayini et al., 2010). However the study was compromised due to a small sample size and no data to describe total smoking history or the presence of specific confounders like vascular disease (Ghalayini et al., 2010). In a separate study that excluded patients with cardiovascular disease, former smokers had same significantly increased risk for ED as current smokers (He et al., 2007). Thus, it would appear that even without outright vasculopathy, a history of smoking represents the presence of a silent vascular insult that persists over time.

However, not all of the damage appears to be permanent. There is currently mounting evidence that some damage is reversible if smoking is stopped prior to middle age and is not restarted (Pourmand et al., 2004; Sighinolfi et al., 2007; Harte & Meston, 2008; Chan et al., 2010).

Interestingly, a short smoking abstinence period of 24–36 hours in heavy smokers can allow for significant improvements in tumescence (Guay et al., 1998; Harte & Meston, 2012) and vascular erectile parameters (Sighinolfi et al., 2007). Along this vein, in a cohort of 143 men with ED who quit smoking, >50% reported improvements in erectile function at 6 months - double the rate of those who were unable to quit (Chan et al., 2010). Effects that persisted for at least one year (Chan et al., 2010). Among patients with no other risk factors, successful smoking cessation via an 8 week trial of nicotine replacement therapy significantly improved erectile function at a 1-year follow-up (Pourmand et al., 2004).

It appears however, that age modifies the chances of regaining erectile function. In the study by Pourmand et al. (2004), improvements were confined to patients less than 50 years old. Likewise, in another study by Chew et al. (2009), those who quit and were under 50 years of age did not show increased risks for of ED. A slightly higher age of 60 years was shown by Austoni et al (2005) to delineate better ORs for former smokers compared to current smokers of similar ages.

Furthermore, the severity of a patients ED may also predict ones response to quitting. In the study by Pourman et al. (2004), of those men who regained erectile function after quitting smoking, 49% had only mild ED at baseline. No men with severe ED regained function – a worrisome statistic since many former smokers are more-likely to have severe ED (Chew et al., 2009). The presence of other vascular risk factors like hypertension or diabetes futher increased the odds of ED in former smokers. Furthermore, men with these comorbities did not show benefits to quitting smoking suggesting that smoking may not present an additional vascular risk if vascular damage from hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease is already present (Austoni et al., 2005).

In summary, large epidemiologic studies do not appear to show a return to baseline risk in men who are smokers. Smaller studies however, do show that younger men (<50 years old) have a better chance of erectile improvement after quitting. Early cessation is necessary to increase the chances of erectile improvement. There also appears to be a physiologic set-point where the presence of severe cardiovascular disease and ED does not respond to smoking cessation.

CONCLUSIONS

In the general population, over half of men over the age of 40 will have some varying degree of ED. Smokers are at even higher risk of developing ED independent of age and comorbidities. There is overwhelming evidence in the literature to support the claim that smoking worsens erectile function through vascular mechanisms (Primarily depletion of nitric oxide). It is yet unclear whether, at a population level, quitting smoking will improve ED rates; however, in controlled trials, gains in erectile function are made by men who do. Unfortunately, the current literature suggests that this improvement is limited to younger men with a more minor smoking history and a lack of comorbidities.

Figure 1. Interplay of neuronal and endothelial effects on vascular relaxation.

The main mediator of penile arterial relaxation is nitric oxide (NO). NO is released directly from neurons and indirectly via endothelial production. Cigarette smoke has been shown to directly inhibit both neuronal and endothelial isoforms of nitric oxide synthase (NOS). In addition, superoxide anions from cigarette smoke directly degrade NO. Rho-kinase (ROK) is upregulated in men who smoke thus activating myosin light chain (MLC) phosphatase that prevents NO-induced relaxation.

Acknowledgments

JRK and RR are NIH K12 Scholars supported by a Male Reproductive Health Research Career (MHRH) Development Physician-Scientist Award (HD073917-01) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Program.

References

- Austoni EMV, Parazzini F, Fasolo CB, Turchi P, Pescatori ES, Ricci E, Gentile V. Andrology Prevention Week centres; Italian Society of Andrology. Eur Urol. 2005;48:810–818. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon CG, Mittleman MA, Kawachi I, Giovannucci E, Glasser DB, Rimm EB. A prospective study of risk factors for erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2006;176:217–221. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett AL. Nitric oxide control of lower genitourinary tract functions: a review. Urology. 1995;45:1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler R, Morris AD, Struthers AD. Cigarette smoking in men and vascular responsiveness. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:145–149. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S, Yin X, Wang Y, Zhou H, Song F, Lu Z. Smoking and risk of erectile dysfunction: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. PloS one. 2013;8:e60443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Georgakopoulos D, Bull C, Thomas O, Robinson J, Deanfield JE. Cigarette smoking is associated with dose-related and potentially reversible impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation in healthy young adults. Circulation. 1993;88:2149–2155. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SSLD, Abdullah AS, Lo SS, Yip AW, Kok WM, Ho SY, Lam TH. Smoking-cessation and adherence intervention among Chinese patients with erectile dysfunction. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew KK, Bremner A, Stuckey B, Earle C, Jamrozik K. Is the relationship between cigarette smoking and male erectile dysfunction independent of cardiovascular disease? Findings from a population-based cross-sectional study. J Sex Med. 2009;6:222–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitaley K, Wingard CJ, Clinton Webb R, Branam H, Stopper VS, Lewis RW, Mills TM. Antagonism of Rho-kinase stimulates rat penile erection via a nitric oxide-independent pathway. Nat Med. 2001;7:119–122. doi: 10.1038/83258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean RC, Lue TF. Physiology of penile erection and pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin North America. 2005;32:379–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demady DR, Lowe ER, Everett AC, Billecke SS, Kamada Y, Dunbar AY, Osawa Y. Metabolism-based inactivation of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase by components of cigarette and cigarette smoke. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2003;31:932–937. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.7.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derby CAMB, Goldstein I, Feldman HA, Johannes CB, McKinlay JB. Modifiable risk factors and erectile dysfunction: can lifestyle changes modify risk? Urology. 2000;56:302–306. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbendary MA, El-Gamal OM, Salem KA. Analysis of risk factors for organic erectile dysfunction in Egyptian patients under the age of 40 years. J Androl. 2009;30:520–524. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.007195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gades NM, Nehra A, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Girman CJ, Rhodes T, Roberts RO, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ. Association between smoking and erectile dysfunction: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:346–351. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghalayini IFA-GM, Al-Azab R, Bani-Hani I, Matani YS, Barham AE, Harfeil MN, Haddad Y. Erectile dysfunction in a Mediterranean country: results of an epidemiological survey of a representative sample of men. Int J Impot Res. 2010;22:196–203. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2009.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano FA, Leriche A, Jaudinot EO, de Gendre AS. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction among 7689 patients with diabetes or hypertension, or both. Urology. 2004;64:1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guay AT, Perez JB, Heatley GJ. Cessation of smoking rapidly decreases erectile dysfunction. Endocr Pract. 1998;4:23–26. doi: 10.4158/EP.4.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Oldham MJ, Kleinman MT, Phalen RF, Kassab GS. Effect of cigarette smoking on nitric oxide, structural, and mechanical properties of mouse arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2354–2361. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00376.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harte CB, Meston CM. Acute effects of nicotine on physiological and subjective sexual arousal in nonsmoking men: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Sex Med. 2008;5:110–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harte CB, Meston CM. Association between smoking cessation and sexual health in men. BJU Int. 2012;109:888–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Reynolds K, Chen J, Chen CS, Wu X, Duan X, Reynolds R, Bazzano LA, Whelton PK, Gu D. Cigarette smoking and erectile dysfunction among Chinese men without clinical vascular disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:803–809. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka T, Hata T, Soga J, Fujii Y, Idei N, Fujimura N, Kihara Y, Noma K, Liao JK, Higashi Y. Increased leukocyte rho kinase (ROCK) activity and endothelial dysfunction in cigarette smokers. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:354–359. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupelian V, Link CL, McKinlay JB. Association between smoking, passive smoking, and erectile dysfunction: results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007;52:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Esposito K. Diabetes and sexual dysfunction: current perspectives. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014;7:95–105. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S36455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannino DM, Klevens RM, Flanders WD. Cigarette smoking: an independent risk factor for impotence? Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:1003–1008. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills TM, Chitaley K, Wingard CJ, Lewis RW, Webb RC. Effect of Rho-kinase inhibition on vasoconstriction in the penile circulation. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1269–1273. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner M, Seftel AD, Nehra A, Ganz P, Kloner RA, Montorsi P, Vlachopoulos C, Ramsey M, Sigman M, Tilkemeier P, Jackson G. Prognostic utility of erectile dysfunction for cardiovascular disease in younger men and those with diabetes. Am Heart J. 2012;164:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natali A, Mondaini N, Lombardi G, Del Popolo G, Rizzo M. Heavy smoking is an important risk factor for erectile dysfunction in young men. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:227–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH Consensus Conference . Impotence. NIH Consensus Development Panelon Impotence. JAMA. 1993;270:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orosz Z, Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Smith K, Kaminski PM, Ferdinandy P, Wolin MS, Rivera A, Ungvari Z. Cigarette smoke-induced proinflammatory alterations in the endothelial phenotype: role of NAD(P)H oxidase activation. Am J Physiol HeartCirc Physiol. 2007;292:H130–139. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00599.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluffo G, Calcerrada P, Piacenza L, Pizzano N, Radi R. Superoxide-mediated inactivation of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite formation by tobacco smoke in vascular endothelium: studies in cultured cells and smokers. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1781–1792. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00930.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourmand GAM, Rasuli S, Maleki A, Mehrsai A. Do cigarette smokers with erectile dysfunction benefit from stopping?: A prospective study. BJU Int. 2004;94:1310–1313. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajfer JAW, Bush PA, Dorney FJ, Ignarro LJ. Nitric oxide as a mediator of smooth muscle relaxation of the corpus cavernosum in response to nonadrenergic noncholinergic neurotransmission. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:90–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201093260203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabsigh R, Fishman IJ, chum C, Dunn JK. Cigarette smoking and other vascular risk factors in vasculogenic impotence. Urology. 1991;38:227–231. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(91)80350-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Shu XO, Li H, Cai H, Liu Q, Zheng W, Xiang YB, Villegas R. Physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption in association with incidence of type 2 diabetes among middle-aged and elderly Chinese men. PloS one. 2013;8:e77919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiri R, Hakama M, Hakkinen J, Tammela TL, Auvinen A, Koskimaki J. Relationship between smoking and erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:164–169. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiri R, Hakkinen J, Koskimaki J, Tammela TL, Auvinen A, Hakama M. Smoking causes erectile dysfunction through vascular disease. Urology. 2006;68:1318–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sighinolfi MC, Mofferdin A, De Stefani S, Micali S, Cicero AF, Bianchi G. Immediate improvement in penile hemodynamics after cessation of smoking: previous results. Urology. 2007;69:163–165. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan ME, Thompson CS, Dashwood MR, Khan MA, Jeremy JY, Morgan RJ, Mikhailidis DP. Nitric oxide and penile erection: is erectile dysfunction another manifestation of vascular disease? Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:658–665. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorve VS, Kshirsagar AD, Vyawahare NS, Joshi VS, Ingale KG, Mohite RJ. Diabetes-induced erectile dysfunction: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. J Diabetes Compl. 2011;25:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Zhang H, Gao Y, Tan A, Yang X, Lu Z, Zhang Y, Liao M, Wang M, Mo Z. The association of smoking and erectile dysfunction: results from the Fangchenggang Area Male Health and Examination Survey (FAMHES) J Androl. 2012;33:59–65. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.110.012542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Garban H, Ng C, Rajfer J, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF. Effect of long-term passive smoking on erectile function and penile nitric oxide synthase in the rat. J Urol. 1997;157:1121–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]